Chapter eight

Future orientation

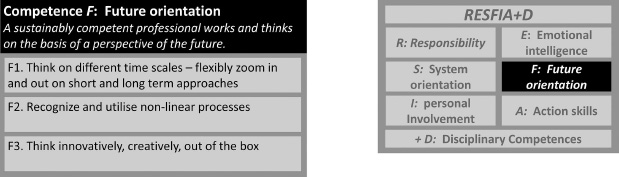

The Competence (Figure 8.1):

A sustainably competent professional thinks and acts on the basis of a perspective of the future.

You probably spend a lot of time in cars, perhaps at the steering wheel. You make sure that your front window is clean and clear so that you can constantly see where you are heading. If this is not the case – perhaps you covered the windshield because of severe frost to prevent ice crystals – and you start driving while the cover is still on, you won’t get very far. A hundred yards later, you will probably end up wrapped around a lamppost, or worse, you’ll hit another car or a child crossing the street. Of course, nobody would do that. You would be a fool if you did, you don’t go on the road blindly!

Have you ever realized that when riding in a car, you actually travel in two directions at once? First, when you drive on the road, you cover a distance expressed in miles or kilometers. Second, while you drive, you also move in time, and this is expressed in minutes or hours. Even if you are standing still, not adding any miles to your traveling distance, your temporal motion continues: hour upon hour, day by day, year after year. Why, then, do so many people travel blindly toward the future?

It’s funny. Sometimes when I present to an audience, I ask a couple of people where they want to be in ten years, or in 25? What do they wish to have accomplished? Which dreams would they want to have fulfilled? Who would they want to be by then? Almost every time, these people seem to be surprised: they never thought about it. Usually, they like the question all right, and they start thinking out loud. Please do the same and ask somebody you meet this question. You will see what a remarkable conversation you will have. By the way, what would you say if I posed the question to you?

A comparable question can be asked at a different level. I tend to ask entrepreneurs – if possible, in front of a large audience since it always leads to fascinating dialogues – why they think their companies will still exist in twenty years. Without exception, the reactions are interesting, and nearly every time, you will see that the interviewee has never even thought about it. So, you get something like this: “Of course, my company will still exist ’cause I deliver excellent products or services!”

Right. It’s always beautiful to see how an entrepreneur believes in his or her own product, but whether that is sufficient is doubtful. What if, between now and in twenty years, this excellent product becomes obsolete or is outperformed by something even better or cheaper? What if the people twenty years from now just don’t need your product, excellent as it may be? Yes, entrepreneurs who don’t think about such things travel blindly toward the future.

Is society as a whole also blind to the future? Sometimes it is, sometimes it isn’t. Of course, you can’t predict the future. But at least you can think about it, and that happens surprisingly seldom. Future blindness is what you see all around. Like when national politicians discuss political decisions with extremely long consequence periods without the people in the country participating in a general discussion concerning their wishes about what the country should look like in 50 years. For example, how much wealthier would they want to be by that time? Future blindness is also seen when oil companies happily report that oil fields under the oceanic bed of the North Pole will soon be exploitable as – thanks to global warming – the polar ice will disappear entirely during the summer.

“You would be a fool,” I just wrote. “You don’t go on the road blindly!” Well we do, and more than just sometimes.

This chapter is about the dimension of “time.” It’s the complement of the former chapter, in which “place” had the key role. Below are the three achievements I will describe:

- Think in different time scales – flexibly zoom in and out of short- and long-term approaches

- Recognize and utilize non-linear processes

- Think innovatively, creatively, and out of the box

8.1 Short- and long-term

It was an emerging crisis. As Miami Beach was bracing itself for yet another October king tide, when streets routinely flood even though no cloud is in sight, Mayor Philip Levine announced on the city’s public TV channel, “We have storms. We have rising sea level, due to climate change, but we’re taking the offensive, aggressive action to making sure our city is viable and livable for the next 500 years at a minimum.”

The person at the center of helping Miami Beach realize these ambitious plans is the city’s new Chief Resiliency Officer, Susy Torriente. “I’m not an engineer and not a scientist,” Torriente says. “I’m a communicator and collaborator. I am giving our experts the tools we need.” Working both on an operational and a strategic level means she has to recognize interconnections, she says.

Ideally, short- and long-term perspectives should be intertwined in a natural way. So how does one tackle long-term sustainability issues such as sea level rise? Torriente shares her approach: “These issues may be 50–100 years out, but in local government, you deal with a one-year budget and election cycles. The first plan I worked on was a five-year plan, but I would always bring it back to looking at short-term solutions and ask, how do you break it down into segments? It’s a matter of what’s doable.” Working in a political environment often means seizing opportunities when they arise, as different administrations can be more or less supportive. “When the stars align,” Torriente says, “it is time to push forward.”

Torriente thinks that aside from being aware of how government works, a vital skill for city managers like her is to have the ability to zoom in and out to see the big picture. “You have to observe, listen to the experts, and make connections … I ask incoming young city interns to close their eyes and imagine the city in 30 years when they are going to be in the top position.” Innovation plays a significant role, too. The need drives innovation,” Torriente believes. “We have to challenge ourselves, and we have to take risks. We’re writing the ‘textbook’ now. We need to train our staff and build capacity. In the face of climate change, we have to deliver services differently.” NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association), for example, offers climate awareness training, she notes. Torriente also embraces creative solutions. In addition to traditional “gray infrastructure,” she increasingly promotes “green infrastructure, such as dunes and living shorelines” to create a natural environment that can protect residents.

Before accepting the position in Miami Beach, Torriente served as Assistant City Manager in Ft. Lauderdale and participated in a program called CityLinks, a collaboration between South Florida and Durban, South Africa, another coastal city threatened by rising sea levels. Torriente, who has also attended resiliency meetings in Canada and Germany, accomplished several goals. She was able to converse with international experts to disseminate best practices and also to share her insights when she was invited to teach a course to Durban’s municipal employees, a unique experience she found “very exciting and rewarding since they can now replicate our strategies and action from South Florida to South Africa.” Durban is implementing a climate compact based on South Florida’s model.

What Miami Beach or the many other affected coastal areas will look like in 500 years cannot be foretold, but with someone like Susy Torriente in charge, the city’s residents and the mayor alike can face the next king tide knowing that 1-year, 5-year, 20-year, and 100-year adaptation and mitigation plans to counteract the impact are in place.

The achievement

You think on different time scales, distinguishing between a short-term and a long-term approach.

This means:

- You zoom in: you analyze the opportunities and consequences of your work for the short term.

- Your short-term approach to the problem is aimed at tackling symptoms. (This is the operational approach).

- You also zoom out: you investigate the options for the long term, if necessary even years ahead, to improve your work fundamentally and in an innovative way.

- Where solving problems is the issue, you primarily aim at eradicating their causes. (This is the strategic approach).

- This zooming in and out in time is done by you regularly and fluently, thanks to which you have continuous attention for both the short- and the long-term.

Zooming in and out in time is easy to understand if you imagine the following situation. You are sitting quietly at home one night. Outside it is raining cats and dogs, but inside it feels nice and cozy until you suddenly realize that water is dripping from the ceiling. The roof is leaking! What do you do? Well, or course, the very first thing you do is get towels, wipe up the water, and place some buckets. The leaking roof is one thing, but you don’t want your costly hardwood floor or broadloom carpet to get ruined as well.

Next, you have to find the cause. Something is wrong with the roof. Maybe some roof tiles have shifted, or perhaps a watertight strip is no longer watertight. In other words, you find the cause and repair the damage. You might even take another big step and replace the entire roof, or as a last resort, you may find another house and move. Wiping water up with towels and placing buckets – these are examples of short-term actions. They don’t address the causes, but they prevent further damage. This is what acting operationally means.

Repairing the roof represents a more profound approach. If you don’t do it, you will still be emptying buckets next year. It is a tactical approach, aimed at a longer term than the towel operation. It’s not a matter of minutes; rather, it takes days or weeks.

When you replace the roof or even move to another place altogether, then you apply a genuine long-term view. We call this a strategic approach, which involves considering many issues, not just acute problems. For example, you would ask yourself, “How do I want to live in twenty years?”

To put it a bit more formally:

- A strategic policy aims at the long term, endeavoring to realize fundamental goals based on the mission of an organization or on personal life goals.

- A tactical policy aims at an intermediate term, attempting to realize concrete targets of the organization or of a person, possibly (but not necessarily) derived from the strategic policy.

- An operational policy makes use of methods that can be applied immediately or in the short term, possibly (but not necessarily) based on tactical or strategic plans.

How long is long term? It’s impossible to define it in an absolute sense; it depends on the context. For businesses or communities, the guidelines are as follows:

| Short | = | now or in less than six months to two years |

| Intermediate | = | three to five years |

| Long | = | up to 20 or 100 years (or more) |

- Many exceptions to these rules exist. For example, if the roof is leaking, repairs (= intermediate to long-term) occur within a matter of days or weeks at the most – I hope.

A sustainably competent professional is able to oversee and connect these various terms, from short to long, in a harmonious way.

An earlier competence from Chapter 6 dealt with “Parts and wholes.” In that section, I described how you zoom in and out within a system, from its details to a helicopter view and back. The same approach, alternating between the analytical and the holistic view, is not only needed within the dimension of space, but also with the other dimension: time.

Focusing on the immediate future (the king tide causing flooding next week) while also envisioning the future of the next generation (12 inches of predicted sea level rise over the coming decades means causeways and bridges need to be elevated) and being able to flexibly move from one time frame to the other – that is what a sustainable professional does.

This is not easy because the short term usually draws more attention than the long term. Many politicians look only to the next election, managers to the upcoming shareholder meeting, and employees to their approaching performance review. From sustainable professionals you may expect better. Do you remember the “rule of thumb for making sound decisions” in Chapter 2? It deals with the distinction between short- and long-term. The long-term consequences should always weigh in. What is your opinion about, let’s say, the extraction of shale gas, for which the ground has to be fracked – that is “shattered?” What will people think about fracking in 100 years? Maybe they will think it’s all right that we did this for a few decades, maybe not. What is your guess?

Someone who does not want to travel blindly toward the future, someone who does not want to crash or accidentally hit a child in ten or 100 years, looks ahead and anticipates in order to reach an agreeable future. This is the very first principle of sustainable development.

8.2 Not just linear

1 + 1 = 2, right? That’s what you learn in school, and 10 + 10 = 20, 20 + 20 = 40, and so on. It’s not just theory; you can see it in real life all around you, too. That is, if you don’t see past the end of your nose. Please take a look:

- 1 Soccer: When I sign players that cost twice as much, my team will score twice as many goals. 1 + 1 = 2.

- 2 Merger: When I double the size of my company through a merger, the overhead will double, too (and therefore stay the same, relatively speaking). 1 + 1 = 2.

- 3 Money: When I am twice as rich, I will be twice as happy. 1 + 1 = 2.

- 4 Traffic: When I double the number of lanes on a highway, twice as many cars can pass without causing a traffic jam. 1 + 1 = 2.

- 5 Criminality: When I double the punishment, safety will increase by 100% as well: 1 + 1 = 2, so crime rates will halve.

Dear reader, no doubt it is clear to you that these kinds of “laws” are incorrect. I call them doubling laws. They are hardly ever true, and so perhaps they should rather be called doubling myths. Intuitively, we all think, now and then, that processes will develop “normally” and won’t result in anything unexpected. Our instincts are tuned this way. As a rule, we expect linear relations. In other words, when something is doubled, some other thing will double, too.

Such linear thinking can also be found in a more figurative sense, not literally as a doubling law or a myth. Reality is supposed to be simple and easy even though it is actually more complicated. I will give you a few examples:

- 6 Healthcare: When the citizens of a country become healthier, medical expenses will decrease.

- 7 Competition: When commercial competition is introduced in service sectors such as public transportation or healthcare, the quality of these services will improve.

- 8 Nature: People have evolved from nature, so when I buy and eat natural products, I will be healthier.

- 9 Conservation of misery: War, poverty, and hunger will never be eradicated from the Earth because they have always been there. There is nothing new under the sun. History just repeats itself.

- 10 Medical technology: In a few decades, we will be able to extend human life expectancy to 150 years.

One of the characteristics of sustainably competent professionals is that they don’t naively believe in such simplifications of reality. They don’t fall for easy thinking errors; they dig deeper. Reality is almost always non-linear.

When I was thinking about a good way to illustrate this principle with a story from real life, I soon arrived at the example of traffic. Traffic conceals a lot of non-linear traps, concerning themes such as velocity, energy consumption, safety, congestion, and more.

The “braking distance,” the number of feet you need to stop your car completely, presents a clear example. When you watch the behavior of drivers on the highway, you get the impression that many of them, especially the tailgaters, think the braking distance is (at the most) linearly proportional to the velocity – in other words, a doubling law. However, it isn’t. At a speed of about 40 mph, a realistic breaking distance is 76 feet (in dry weather conditions). At a twice as high velocity, 80 mph, the breaking distance increases to more than 300 feet: four times as large. That’s not all. If a line of cars is moving on the highway and just one driver plays with his cellphone, causing him to take two extra seconds to react, his breaking distance shoots up to around 550 feet! Bad luck for those behind him. If something happens that requires the entire line of cars to stop quickly, not just this single driver will suffer, but – thanks to him – many others who did drive carefully.

Thinking about traffic, I came to the conclusion that there is only one person I know who is able to explain these things the best: “Mister Traffic” himself. A Dutch TV personality well known for his peppy remarks, Koos Spee, a.k.a. Mister Traffic, served as a district attorney until his retirement and was responsible for the Netherland’s national traffic policy for many years, advising government ministers and directors. Once, Mister Traffic commented on a young motorcyclist who did not seem to know the traffic regulations: “In my opinion, it’s been quite a few years that people could win their driver’s license in a game of dominoes. Nowadays, you actually need to pass a test for it, so I think, he was pretending to be more ignorant than he actually is.” On another occasion, Spee made remarks about young men who spend a lot of money to embellish their cars (in their own eyes). “Yes, I perfectly understand,” he said in a wry tone. “Those boys put their heart and soul into it, and it may cost some. There will come a time when they need all that money for something else, and then it will end all by itself.”

I sent Spee an email with a request for an interview for my book, and I received a kind reply from him, inviting me to come to his home. And so, on a nice morning, I was sitting on the porch in the backyard of Koos Spee’s house. I had prepared myself by reading one of his books in which he writes ironically: “I can imagine that as a cyclist you don’t always see the necessity to stop at a red traffic light, but many of those who passed the stop signal are now parking on the wrong side of the grass” (or six feet under).

In his online blog, Spee cracks a few doubling myths. One of them goes like this: if all motorists would drive twice as fast, twice as many cars could pass the road. Is this true? Of course, it isn’t. In reality, you will get maximum road capacity of a highway when everybody drives at 50 mph. When we try to travel with 75 mph, we get jolts and jerks, accelerating and braking – congestion. In symbolic math: 50 + 25 = 30.

During the interview, I started talking about widening a highway by adding extra lanes, a practice that is also very popular in the United States, where space is so abundant. When my co-author Anouchka Rachelson, who lives in the United States, read this, she immediately agreed and remarked, “Right now, they are widening the four lanes of a highway near my house to six lanes, which won’t ease the congestion but just invite more people to ride on the highway.” This is myth number 4 in my list above. Spee said, “Yeah, look. If everybody behaved rationally, a twice as wide highway might indeed double the capacity, but that is not what happens as most people have a tendency to drive in the left lane. That leaves a large part of the road capacity unused.”

Halfway through the interview, I mentioned myth number 5 (in the list above), regarding raising punishments and penalties. Many people have the expectation that this would lead to better behavior in traffic, but not Koos Spee. “Raise penalties? That doesn’t work at all!” he says emphatically. “The probability of detection, that’s the only thing that really works.” He adds a splendid metaphor. “In the Middle Ages punishments were extremely heavy. Pickpockets were hung publicly at the center of the town square. But let me tell you, never were more pockets picked than during such an execution! So, the probability of detection matters, not the size of the penalty. The subjective probability that is. Pain in the purse! If people believe they won’t get caught, they don’t change their behavior. Speed traps with recognizable police cars or with speed cameras in fixed positions hardly help because then people know it is ‘safe’ further down the road, so I gave unmarked cars of different brands and models to all police departments. They swap them now and then to prevent motorists from recognizing them in the long run.”

After the interview, I drove home observing traffic carefully. So many lanes! And yes indeed, the right lane only carried the odd truck and the rest of it was empty. Even the second lane was hardly used. Most motorists were engaged in a kind of battle for the two lanes on the left. Me too!

In 1996, Spee started as the national district attorney for traffic, and two years later he founded the Bureau for Traffic Enforcement. This had an immediate effect on the Netherland’s traffic policy. During Spee’s tenure, the number of traffic fatalities was cut in half. Of course, this reduction was not due to Spee alone. Here too, it is not as simple as 1 + 1 = 2. Cars have become safer over the years; however, in neighboring countries, the number of fatalities decreased far less – until a few years ago when these countries adopted Spee’s traffic policy. You can safely say that Koos Spee saved hundreds of lives, although you will never be able to point at those whose lives have been spared because they did not have an accident.

In recent years, environmental quality related to traffic has gotten a lot of political attention. Spee tells the story of a conversation with a cabinet member: “She wanted to set the speed limit on one of the highways at 45 mph because a nearby village had a lot of trouble with exhaust gases. It appeared that residents inhaled the equivalent of 17 cigarettes each day. I said to the representative: You shouldn’t do that because then big trucks will constantly shift gears, down and up, down and up. From all this breaking and accelerating, exhaust will actually increase. You won’t have that with a limit of 50 mph instead 45 mph. So if you want me to uphold the law, I am fully prepared to do so, but only if you make it 50 – and that is what happened.” Spee’s anecdote serves as a nice example of a non-linear effect: Sometimes, considering the emission, 45 is larger than 50.

Concluding the fascinating interview – Spee could have gone on for hours telling me many more interesting stories – I asked him, “But Koos, this traffic enforcement, isn’t that like mopping the floor while keeping the water running? Just now when I drove from my house to yours in an hour or so, I saw quite a few tailgaters, people on their cellphones, and road hogs!”

“Yes,” Spee replied, “but if we don’t mop, we’ll certainly drown.”

The achievement

You recognize and utilize non-linear processes.

This means:

- You know the difference between linear and non-linear processes: both in a literal and a figurative sense.

- You describe non-linear, perhaps unexpected developments within your own work.

- You make use of this distinction to realistically estimate the chances, risks, and consequences of your work.

- Based on that estimate, you design your work in such a way that it fits optimally with sustainability. To this purpose, you focus, for example, on the goals, the working environment, and the methods you apply.

Rarely are causes and effects correlated linearly. That is because the systems we deal with – the road network, healthcare, the economy, the climate, etc. – are complex. Many causes, circumstances, effects, and side effects influence one another mutually. This creates feedback loops through which the effects influence the causes. Positive feedback increases the effects (1 + 1 = 3), negative feedback decreases them (1 + 1 = 1 ½, or 1, or even 0). When many such feedbacks exist, the behavior of a system can be incredibly hard to predict. That is the reason why it is impossible to reliably predict the future, where you have to deal with every imaginable system, all actively interacting with one another. You cannot simply extrapolate current trends from the past to the future; developments rarely continue as they did in the past. If, as a professional, you are sustainably competent, you know this and take it into account.

Ah, yes. Before I finish this section, you may want to know why the ten examples I mentioned are less linear than some people think. Here are the reasons.

- 1 Soccer: Adding expensive new players to a team can often be disappointing. The quality of a soccer team depends primarily on the team, rather than on individual players. If the team is strong, you may get: 1 + 1 = 5 and the championship. If not, 1 + 1 = 1 ½ at most. If you’re unlucky: 1 + 1 = 0 and maybe a demotion.

- 2 Merger: Alas, a bigger organization inevitably calls for more bureaucracy, formally or hidden. In this case, 1 + 1= 3 applies, which in this context usually is not considered a blessing.

- 3 Money: People who are really poor can be unhappy, for example, due to hunger or lack of medical care. However, beyond a certain level of prosperity, more money at best brings some extra happiness for a short while. It does not last as research has repeatedly proved. In management theory terms, money is a typical hygiene factor or work environment factor, just like washing your hands: less decreases happiness, but more does not necessarily increase it. In other words, 1 + 1 = 1.

- 4 Traffic: You already received an important explanation from Mr. Spee. There are other reasons why extra lanes don’t always lead to less congestion. For example, there could be a bottleneck on the next highway, which did not get new lanes, a bottleneck near roadwork, or a congested exit ramp. An accident that involves a truck leaking hazardous fluids and blocking the entire highway including the new lanes could be the cause. In most cases, new lanes render at best something like 1 + 1 = 1 ¼.

- 5 Criminality: Traffic infractions are not the only area where stiffer punishment hardly ever leads to better behavior. Time after time, scientific research has proved that crime rates strongly depend on the probability of detection and far less on the severity of the punishment: 1 + 1 = 1.

- 6 Healthcare: Many people intuitively expect that a better average state of health leads to a reduction of healthcare costs, something like 1 + 1 = 1 ½. However, that is not correct. You see, even the people who stay healthy for more years will eventually get old and infirm, and they will cause the same medical expenses, only a few years later. In the years between, they will incur medical costs, too, albeit relatively low. The result is an increase in healthcare costs, not a decrease: 1 + 1 = 2 ½.

- 7 Competition: When the primary goal of an organization shifts from services to profitability, it usually appears that the quality of the services decreases rather than increases.

- 8 Natural: Oh well, nicotine is a natural product, and so are cocaine and even strychnine, a popular rat poison.

- 9 Conservation of misery: Nothing new under the sun? Right. 200 years ago, people could say, “We have never flown, so that will never happen.” Now look at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International or Heathrow! In reality, history has never repeated itself. There is no law in nature prohibiting the eradication of war, hunger, or other misery. However, after thousands of years of bloodshed all over Europe, there has not been a war between EU countries in more than 50 years – a sensation, a unique achievement – so keep your courage and strive for peace and prosperity for all.

- 10 Medical technology: Medically seen, this may be true, but from an ecological viewpoint, it certainly is not. It would present a catastrophe! If everyone got twice as old, preserving the present health and prosperity, it would double the world population, which would go far beyond the biocapacity of our planet. Already, it will be hard enough to feed and house some eleven billion people, halfway into the twenty-first century. In reality, we would not get even close to doubling the world population because long before that, the ecological system and (hence) the economy would collapse – a global catastrophe and the deaths of billions of people: 1 + 1 = 0. Dear medical researchers, why don’t you think beyond the boundaries of your own discipline? Where is your societal responsibility?

8.3 Innovative, creative, out of the box

It is amazing what you can accomplish as an individual if you have the guts to take that first step, go beyond the well-known boundaries, and harness the power of community. This is most certainly true for Nick Papadopoulos, social entrepreneur and co-founder of CropMobster, an online local food network that uses crowdsourcing to prevent food waste, boost food security, and help local farmers as well as food businesses grow and gain awareness.

“One Sunday night, in 2013, I was standing in a large walk-in cooler next to a crate of premium vegetables that I knew were going to rot and be thrown out if I didn’t do something about it. At that moment, I had an idea, and so I went home and started experimenting with social media to create an alert. The next morning, a mother in a minivan stopped by and picked up the food. It was a beautiful ‘win-win’ outcome for everyone!” Nick, who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area, remembers.

Encouraged by this experience, Papadopoulos created his crowdsourcing organization CropMobster. “I thought, all this value is being wasted. Why don’t we create a model to connect people and find a home for the vegetables, turn loss into value? We built the initial website in four days. The name CropMobster was inspired by the idea of a flash mob, only one that specializes in food. The idea resonated. With a little bit of innovation and the swarm effect, it took off. When we first started, we couldn’t have imagined the various ways our work would unfold for larger scale impact or challenges we would face. Now, with a few years under our belt, we have good data and a large set of experiences to define a bit more what the impacts of decisions will be.”

Nick is passionate about his project: “We are becoming a local food hub and network that is helping facilitate a range of positive impacts. There are multiple benefits: we get healthy food to those in need, help local businesses drive sales, prevent food waste, keep discarded food and organic out of the landfill, and connect with an inspired community – that’s when beauty happens. We’re at the nexus or overlap where the sharing economy and circular economy meet.”

The CropMobster website offers a variety of service categories ranging from deals, donations, trades, and more. Offerings include free compost-ready vegetables and chickens looking for a new home, gleaning gatherings during which community members can collect left-over crops such as lettuce and tomatoes, and posts to sell used tools and machinery like the recently listed John Deere 365 hay swather. In addition, there are announcements of local events such as the “Don’t Chuck the Pumpkin” initiative around Halloween and trade offers like “homemade sourdough bread for persimmons.”

To anticipate the needs of the community, the CropMobster team engages with its customers. Papadopoulos describes it as follows, “We try to take frequent steps back to see the forest from the trees and look at things from an interconnected systems perspective. We also spend a lot of time listening, observing in dialogue with people using our platform to understand their needs and develop creative, crowd-sourced ways to meet those needs. Finally, we try to ‘stack functions’ or benefits to make sure that one idea or solution has a range of positive impacts at once. When you can stack impacts and benefits, there is the opportunity to really generate momentum and make progress.”

Of course, there are always moments when Nick has to make business decisions and weigh alternatives and their consequences: “When confronted with decision points or challenges, we try to list out all of the various paths or choices we could make and then list the pros and cons of each. We also try to think of various scenarios in the future. Finally, trust in our clients and community members is everything. We ask ourselves, ‘Will we be building trust or degrading trust with a certain path of action?’ Everything we do – whether internally as a team or with the CropMobster community – is based on trust, transparency and trying to be as authentic and real as possible.”

Papadopoulos is proud of the fact that CropMobster has “inspired people and even other platforms and models to tackle the issues of food waste, food security and local farm and food business viability.” For those just starting out, he recommends “Keep your costs low, and don’t worry about making money at first. Instead, be a scout for problems and opportunities. Cultivate your patient listening and observation skills. Strive to identify significant ‘win-win’ opportunities to solve problems and create value in communities and systems.”

The achievement

You think innovatively, creatively, and out of the box.

This means:

- You see past the end of your nose: from the directly visible wishes and needs of people or organizations, you derive the underlying needs or expectations.

- Stepping out of the box, you design creative and innovative alternative ways to meet these underlying needs.

- For each of these alternatives, you discover the main consequences, and you weigh them against each other.

- Based on your conclusions, you arrive at innovative and at the same time realistic recommendations, decisions, or actions.

As I mentioned earlier, according to the Brundtland Report, sustainable development is:

“a development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

Apparently sustainability is about fulfilling needs and the ability to continue doing so in the future. This raises a fundamental question: which needs?

Is a second car for everyone such a need? How about a second home and a yacht in the harbor? What about exotic foods flown in by plane? Clearly everything is not feasible; what our planet can offer us has limits. Therefore, if we want to advance sustainability, it is important to discuss the kinds of needs we have.

A clever tool for this is Maslow’s well-known hierarchy of needs pyramid, which distinguishes five levels of needs – from basic needs such as food and oxygen up to more psychological needs like esteem and self-actualization. For example, imagine you would like to drink a cup of coffee. Why, actually? Which need to you want to fulfill? Are you thirsty? (physiological need, Level 1 of Maslow’s pyramid). Would you like to hold something in your hands? (safety need, Maslow’s Level 2). Or do you feel a need for coziness and human interaction? (love and belonging, Maslow’s Level 3). In other words, which function does the cup of java have to serve?

The example of the cup of coffee shows that what constitutes a need defies simple definitions because appearances can be deceiving. In many cases, the expressed needs differ from the real ones. Often people have a feeling that they would want to satisfy a certain need, while in reality – perhaps without being aware of it – they cherish some other deeply-rooted need. The function of a cup of coffee, a good conversation, a diploma, a partner for life, a job, a private business, or a car is in many cases not the one you might think of at first sight. What is the underlying function, the need behind the need? Could it be a need you aren’t even conscious of?

Every professional has the task to fulfill needs. Check it out! Doctors and nurses fulfill patients’ needs for improved health. Researchers and teachers fulfill needs for knowledge; managers the need for guidance, control, or support; producers and shop owners the need for products; consultants the need for advice; and so forth. Which needs do you fulfill, and for whom?

Now, as a professional, you can simply do what you are asked to, but you might also think critically about your task and initiate your own changes or additions. This book is filled with beautiful examples. One way to begin is to think deeply about which needs you really are fulfilling. Think about the need behind the need. If you do this, you start thinking out of the box, and you embrace wild creativity and splendid innovations. You give yourself the opportunity to find totally new ways to fulfill human needs now and in the future.

A fine method to discover needs behind needs is a “function analysis.” When you apply this method, you return mentally to your early childhood – when you were about two or three years old – to the “why” phase. In short, whenever a need is mentioned, you are going to ask “Why?”

Look at a concrete example.

| When someone tells you: | You ask: | |

| 1 | I want to buy a refrigerator! | Why? |

| 2 | Because I want to have a refrigerator in my house! | Why? |

| 3 | Because I want to keep my food cool! | Why? |

| 4 | Because I want to store food in my house! | Why? |

| 5 | Because I want to have my favorite food available at any time! | Why? |

| 6 | Because I want to have pleasure without limits! | Why? |

| 7 | Because I … (etc.) | |

The fun thing is that each subsequent step opens up a pathway to alternative solutions to fulfill the need.

Statement #1 has just one solution: just buy it, this fridge!

Statement #2 allows for alternatives because you could also try to lease a refrigerator – that fits nicely with the notion of a circular economy – or you could borrow one, or share one with your neighbors or even the whole village. (Steal it?)

Statement #3 offers even more options. Cooling can also be done in a basement, though this may not be suitable for ice cream, I admit.

Statement #4 is about conserving food. However, cooling is not the only option. Instead you can bottle it, can it, freeze-dry it, radiate it, marinate or pickle it (although radiation and salt are not very popular these days) and much more. In short, this statement renders many new alternatives, and so does Statement #5. If you wish to have food available at any time, why not use a delivery service, or how about a pipe structure from the supermarket to your house? One – two – three, and the fresh spinach, harvested half an hour ago, pops out of the hatch!

About Statement #6, pleasure without limits can be had in many ways: playing sports, watching TV, having sex, or installing a new app on your smartphone. Eating is not the only way to have fun!

I did not fill in Statement #7. If I had, there’s a big chance that the discussion would have moved to philosophical issues, perhaps even to the meaning of life. Wonderful, isn’t it?

Function analysis is tremendously important for sustainable development. If you don’t do it and just immediately respond to every desire (see Statement #1), there’s a good chance that we will all end up in a world dominated by even more excessive materialistic consumerism, in which every need is directly translated into a shiny industrial product or a neatly performed, costly service: a facelift, a holiday trip to the Bahamas, you name it. Not only will the financial cost be tremendous, but also from a sustainability angle, this will not be feasible at all. That is why it is so important to search systematically for the needs behind the needs – to ask further. Then, instead of just having one answer to the expressed need, you will get a whole range of possible answers to choose from. This is all the more true if you find innovative alternatives instead of treading down the same old paths. Such a creative way of thinking will enable you to discover the most sustainable way to achieve what Brundtland asks: fulfill the needs of people in the present and in the future.

For the future of a business, function analysis also presents a great instrument. Do you remember the entrepreneur who, at the beginning of the chapter, was convinced that of course his company would still exist in twenty years because it delivers excellent products or services? If every now and then this entrepreneur, preferably together with some independent and creative outsiders, took the time to think about the question of whether his products or services will still be popular within the society of the future, he would gain new insights into the opportunities and threats concerning the continuity of his company. If his chances are low, it may be necessary to redefine the company’s mission, for instance, quit selling refrigerators and instead start leasing them.