Chapter six

Systems orientation

The Competence (Figure 6.1):

A sustainably competent professional thinks and acts from a systemic perspective.

According to Brundtland, sustainability is about two things. It is about the needs of the people who are living now, i.e. about spreading prosperity across the entire planet, and about the needs of the people living later. Those two sides of sustainability are often referred to as two dimensions: “place” and “time.” In Chapter 2, you already encountered the two when they were introduced in the context of responsibility: the consequence scope (= place) and the consequence period (= time).

Competence S, systems orientation, is about one of these dimensions: place. This is the topic of the present chapter. The next competence, to be discussed in Chapter 8, is F, future orientation. The word already shows that it is the complement of competence S, as it deals with the other dimension: time.

The systems we humans have built across the millennia have not been planned or designed beforehand. They have grown more or less by coincidence, as a kind of evolutionary process. It is not surprising that, in the course of time, many faults and errors have slipped into those systems; they are not just small or insignificant errors, but fundamental weaving faults that are deeply embedded. They are the main causes of unsustainability in our world. The extremely unequal distribution of wealth is one such weaving fault. The instability of the global financial system is another one, causing stock exchange markets to collapse once every few decades with deep economic crises as consequences. The 2008 banking crisis, unfortunately, is a recent example. A third example of a weaving fault is the fact that many loops of our production and consumption of goods are not closed, causing scarcity and depletion of resources on the one hand and mountains of waste and clouds of greenhouse gases on the other.

Not every professional needs to be involved in combating the huge global system errors. Weaving faults exist on every scale and in many systems, in and around companies and their branches, communities and cities, households, and families.

Fortunately, we possess a wide range of sources of vigor against these weaving faults with which we can attack them. Such sources of vigor for sustainability are, for instance, the thousands of local, national, and international organizations such as the Carter Center, UNICEF, and Human Rights Watch. Nature is a source of vigor. Visions, texts, and books can be sources of vigor, sources that inspire people to accomplish grand achievements. Science and technology offer tremendous sources of vigor, just as quite a few companies do. And people, of course. Individual people, and not just in the form of responsible and leading civilians. Every sustainably competent professional is a source of vigor for sustainable development. Each of the heroes in this book is one of them. You are one of them, too.

Below are the three concrete achievements of this chapter:

- Think from systems: flexibly zoom in and out of issues, i.e. think analytically and holistically in turn

- Recognize flaws in the fabric and sources of vigor in systems; utilize the sources of vigor

- Think integrally and chain-oriented

6.1 Parts and wholes

Let a hundred flowers bloom,

Let a hundred schools of thought contend.

Anonymous, ca. 600 to 221 BC; often attributed to Mao Zedong, 1956

Sometimes you come across ideas, action groups, or movements, but you are not sure what they actually mean. Do they have a brilliant idea or an intelligent plan offering hope for a sustainable future? Or is it only a nice, romantic but naïve ideal that will never have a significant impact? To me, permaculture is an example of such a doubtful case. I am not yet convinced – time will tell.

Exactly because of this doubt, I think it is great that permaculture exists because sustainable development is not just a matter of neat programs that have already been scientifically tested and validated. That too, of course, but primarily sustainable development is an adventure, a voyage of discovery, in which many exciting new possibilities will be explored. Perhaps many of them will lead to little or nothing, but some of them will prosper and positively conquer the world. That is the thought behind the beautiful ancient Chinese poem about the hundred flowers this section starts with, and the fact that the poem was used or abused by the Chinese party leader Mao Zedong does not alter the case. We live in a magnificent and exciting story.

The Chinese quote fits in two ways with permaculture as it is about flowers and about much more. The practice of permaculture has gained popularity, and its proponents are convinced that it will become even more widely spread. As I said, I don’t know yet how smart permaculture is, but Andrew Millison certainly is smart: he studied horticultural conservation at Prescott College, traveled to Cuba to learn about the Cuban people’s approaches to organic agriculture, designs permaculture projects, serves as a permaculture consultant, and teaches horticulture at Oregon State University.

If you Google “permaculture” and “the United States,” you will find hundreds of places where it is applied. If you simply search “permaculture,” you will find thousands.

According to Andrew Millison, “Permaculture has spread a lot in the US, especially in the last few years. There was a time that demonstration sites were found mostly at urban and suburban scales. In part this was because the social environment of permaculture courses was more alternative, and this limited the types of people interested. But with the rise of online courses and a much broader range of media, a wider range of people are adopting permaculture design and methodology. There’s literally an explosion of interest in this country, at rural, suburban and urban scales.”

Reflecting on the state of permaculture in the United States, Millison adds, “Organizationally, it’s more chaotic in the US than in other countries. Places like the UK have a very organized network of students, teachers and practitioners. The US is so geographically dispersed and polarized politically, that there are many different permaculture organizations and groups that are not collaborative with each other. It’s a bit of the ‘Wild West’ out there in the US Permaculture field. This leads to a lot of competition and innovation, for better and for worse.”

When Andrew Millison receives a phone call from a potential client, the first thing he usually asks is: “What’s your address?” Of course, Millison needs to find out where he will later meet the client, but the more immediate reason is that he wants to take a first peek at the property – right from his office computer. While talking to the new client, he plugs the address into Google Earth and zooooooooms in – North America, the West Coast, and Oregon.

“I can tell someone a lot in five minutes,” Millison says. Looking at the greater landscape, then the major landforms, and finally the property itself, the permaculture designer quickly gains an understanding of the system in which the piece of land his client called about is embedded. “I usually start zoomed out and then zoom in … all the way down to the client,” he explains. “I try to understand where they are, in a psychological sense, and what the best way to communicate with them is. I ask myself, how can I serve them?”

Before Millison, who works mainly with large-scale farms, meets a new client, he spends about an hour researching the property and the landscape surrounding it. “Where’s the water coming from, and where is it going?” he wants to know. “What’s upstream and around the property? How is the soil?” Often, he studies a flood plain map, too, in order to get a better sense of the watershed. When Millison analyzes a new site, he constantly zooms in and out to understand the larger ecosystem. He examines the drainage bases, the ridges, and the hilltops – the natural landscape divisions that shape the system.

“When I look at a property, I look at the patterns and the landscape. They don’t exist in a grid,” Millison explains. These artificial lines and demarcation are what humans have invented. This is why he believes it is necessary to take his horticulture students on field trips where they can experience the landscape in all three dimensions instead of in a two-dimensional space as it is commonly done in the classroom with maps and textbooks. “You can’t teach systems in a flat space!” Millison even brings his students to his house to show them: “This is who I am.” He feels it is vital to “bring his lessons to life” or, using a quote from his wife who teaches at a Waldorf School, to “live into the material.” Whether he teaches or designs, Millison’s objective is to “engage the whole human.”

“A permaculture garden” he concludes, “teaches many lessons. It is a place to connect with soil and feel the security of producing one’s food in a way that is beneficial to nature. I learn so much from being in my garden, and watching it change season to season, year to year. It is the place where I am a direct part of the web of life, and it brings me a lot of good feelings to tend my garden. And I produce a lot of food there as well, and help feed my family and community from my small plot. It brings me peace on a lot of levels: physical, mental and spiritual. The productive capacity of an intensive permaculture garden is quite astounding as well!”

The achievement

You think from systems. You flexibly zoom in and out on issues, i.e. you think analytically and holistically in turn or even simultaneously.

This means:

- You zoom in: you analyze your work in all details, taking into account all separate parts and aspects of the system your work is related to.

- And you zoom out: you regard all those details together as one system. Besides, you are able to position this system within its surroundings, i.e. you treat it as a part of an even larger system.

- This zooming in and out is done by you regularly and fluently. As a result, you pay continuous attention to both minor details and the larger whole.

A system literally is a whole that is composed of constituting elements that interact with each other. The company you may be working for is such a system and also the department within it, as systems often consist of smaller systems while simultaneously being a part of larger systems. A house, a refrigerator, and a human being are systems, too, just like an association, a city, a country, or a continent, a road network, the telephone network, and the Internet.

An ecosystem – as the word says – is also a system: a backyard, a forest, Yellowstone National Park, or the Everglades, as well as the ecological structure throughout California or even North America. And of course, there are virtual systems, for example, a working group cooperating through the Internet or a group of a hundred thousand gamers all over the world playing a MMORPG, a massively multiplayer online role playing game.

The environment of a system may be the immediate physical or societal surroundings, but it may also be a virtual environment, such as the business or intellectual network in which cooperation or competition takes place. For a house, the environment is the street, the city, the country, or the world. For a refrigerator: the kitchen in which it stands, or the house, the street, et cetera. And for the human being: the household, the larger family, the circle of friends or the sphere of professional activities, the community, the country, planet Earth – or even – the entire universe.

Professionals – ranging from, for example, mechanical engineers to prime ministers or presidents – have a tendency to zoom in during a task to the part of the system in which the work takes place. At some moments, this is fine, but preferably the attention does not stay there. When you build a house, you will hopefully have an overall design in mind. At some moment in time, you may be attaching a floorboard, and no doubt you will focus your attention on the nails or screws that you use. However, when the floor is ready, you will stand straight and look at the full result – not just the floor – but the entire house. This is zooming out, when you consider the complete system from a helicopter view. One moment you act analytically, zooming in on the details. The other moment you act holistically, focusing on the larger whole. A good professional possesses the mental flexibility to shift between both on a regular basis.

When you compare a variety of systems, you will find parallels between several of them. Navigating the healthcare system can feel like entering the burrows of a mole maze. An economic system has resemblances with an ecological system, and a roads system with the Internet and with an anthill. So you will discover regularities and rules applicable to several of them. Such comparisons help to design and construct the human world in a sustainable way, for example, by arranging cities and industrial areas using principles that are copied from nature (biomimicry). Closing material cycles is an appealing example of this.

6.2 Sources of vigor against weaving faults

A human being is a source of vigor for sustainability. Take Ricci Silberman, a physician assistant from Arizona, who believes that practicing medicine is “potentially very sustainable.” Having worked with patients that come from “an underserved population that either has no health insurance due to financial constraints or problems getting proper immigration status,” the physician assistant speaks with the experience that comes from treating inner-city patients for nearly 30 years.

Silberman, who co-owns a family practice in downtown Tucson, recognizes flaws in the system: “A significant number of my patients are undereducated and seem to have minimal understanding of personal health and prevention of disease. The most common diagnoses that I see patients for are diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and morbid obesity. Their lifestyles are sedentary, and they exercise minimally. Their choice of foods is usually high-fat, with loads of bad carbohydrates and increased sugar. Hence, this is the reason for all of the diagnoses that they present with.”

Many of Silberman’s patients are clearly at risk, and it often seems that the odds are stacked against them. “Heart disease is the number one killer in the United States,” she explains. Why then does she still feel that medical practitioners like her can find the sources of vigor against systemic weaving faults? The reason is that she “strongly believes in teaching personal responsibility.” If these four diagnoses were treated appropriately, Silberman argues, the numbers of deaths from heart disease would decrease.

That, however, turns out to be challenging. “It is easy for me to prescribe medications, but it doesn’t change the personal choices that people make. This can be very frustrating as a medical provider because I repeat the same information day in and day out.” Even though it does not happen as often as she would like it to, Silberman’s persistence has an impact. Occasionally, she will have patients who have turned around their lifestyle and started exercising and losing weight and making better choices with foods. “What happened?” Silberman will ask during a follow-up visit. “You really started taking care of yourself.” To which her patient responds, “You told me I needed to.” At this point, Silberman often thinks to herself, “I have told the last 500 patients the same thing, and they haven’t listened.” Yet, she reached this person, so Silberman knows she is on the right path.

It takes a lot of patience and conviction to stay on that path. “Over the years, I have attended many conferences,” Silberman contends. “Usually, there is a class on learning to educate our patients in a safe, nonthreatening and nonjudgmental way. I have tried many different techniques to impart this information. Of course, the non-judgmental is heard more clearly, but I am not sure that the end result is any different.”

The best results are obtained when patients recognize that the solution to the problem lies within them. This realization shapes Silberman’s view on the potential for sustainability in medicine: “Patients that take personal responsibility don’t need to rely on the medical system as much for medication and many follow-up appointments. If we had a healthier population, our overall healthcare would not cost as much, and we could focus on prevention of disease as opposed to spending all of our time on treatment of disease.”

Aside from convincing patients to become actively involved in their own health, Silberman thinks medical providers can address the flaws in the insurance system: “In this country, there are many better avenues for sustainability and healthcare than what we currently utilize. One of the problems is what our health insurance covers. I think there is a venue for alternative medicine to be involved. I wish that our basic healthcare coverage integrated holistic medicine with allopathic medicine to help people even further.”

Silberman has evidence that such approaches work. She has discovered a source of vigor, volunteering for Grounds for Health, an organization that practices sustainable medicine in communities that grow coffee. The physician assistant has traveled to Tanzania and Ethiopia to screen women for cervical cancer, the number one killer in women in Third World countries. “This is because they have no access to Pap smears,” she points out. “A method called the single vision method was developed to use in low-resource settings. It entails using household vinegar on a patient’s cervix and waiting a minute or two. If the patient has an HPV lesion – the most common reason women develop cervical cancer – we will treat that patient by freezing the lesion.”

Grounds for Health donates the supplies and the units to freeze the lesions. They also offer transportation and help with treatment if a patient presents with a cancer. “By working with the local people in these countries and training the local providers, we have been able to help local practitioners take over and evaluate and treat many women in rural areas in the country where they usually wouldn’t have access to this screening,” Silberman says. “The national health departments in Tanzania and Ethiopia support the practitioners with resources. So then our work is done, and the program becomes sustainable.”

The achievement

You recognize flaws in the fabric and sources of vigor in systems, and you use the sources of vigor.

This means:

- You are aware, or you investigate, which flaws in the fabric are deeply integrated in the systems with which or for which you work. These flaws are the ultimate causes of un-sustainability.

- You discover which sources of vigor are available in or around these systems in order to correct the flaws in the fabric. These sources of vigor are the powers we possess toward true sustainability.

- You succeed in effectively utilizing or mobilizing the sources of vigor, enabling you to diminish or even eradicate the flaws, or at least to decrease the negative consequences of them.

Recognizing flaws in the fabric and sources of vigor is similar to making a SWOT analysis. The letters SWOT stand for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. The concept is well known in business. When it comes to sustainability, you perform such an analysis more fundamentally than what would be usual and with more than average attention to the long-term future. Often the Triple-P is applied: “people,” “planet,” and “profit.”

Of course, it is preferable to use the conclusions of such an analysis to start real improvements. This requires inspiration, leadership, and vision. It is amazing how many acres of monoculture are beginning to be transformed into permaculture. And think of how many women have escaped cancer because of early intervention methods. Professionals like Andrew Millison and Ricci Silberman can inspire many students, patients, and colleagues every year. If only a part of them will be able to integrate elements of sustainability within their academic study and in their profession, the impact will be enormous. That is how to get a lot of sustainably competent professionals!

6.3 In the chain, in the loop

In 2006, Will Robben bought a cable equipment company that sold equipment for laying cables of all sorts. Within three years, Will thoroughly revamped the company, increasing the turnover by 60%. He did this in such an innovative way that he received two prestigious industry awards.

The company was thriving until the economic crisis broke out in 2009, which brought severe consequences for Robben’s business. The building and construction sector collapsed, and big customers quickly left – one after another. At the beginning of 2011, Robben’s company was legally declared bankrupt. This was the moment when Will started rethinking everything he had done before.

In brief, his conclusion came down to the following: his former customers had a need for certain equipment that they used to buy from his company. The machines Robben had acquired were in use for several hours, but actually most of the time, they were standing still, doing nothing. Wasn’t this a waste, from a sustainability viewpoint? If arranged properly, two or three companies might be able to share just one machine, which would save a lot of things: resources, energy, and construction costs for the production of quite a few machines (that would sit idle most of the time.)

But, hey! Which production company would start to actively promote selling fewer products? Suddenly, a switch flipped in Will Robben’s head.

Why had companies bought machines from his cable equipment company before it went bankrupt? Because they wanted to own the equipment? Certainly not. Because they wanted to use it? If that was the case, buying the devices was not at all necessary. You could rent them, couldn’t you? Fine, but if everyone prefers to rent the devices and no one owns them, there isn’t much to be rented, right? So, what if you start with the companies that already possess the equipment? If you could set up a network consisting of those companies and the companies that might want to lease the machinery, you could perhaps become the mediator who connects the two companies and enables the lease – only for limited amounts of time, aiming at common use of the equipment. This would be good for the people renting since they would not have to buy expensive machines but could instead rent them for much less money. It would also be good for the lenders, who bought the machines for a lot of money, as they would be able to get a return on their investment.

No sooner said than done. In 2011, Will started his new company, Floow2, which does exactly what I described. For example, it mediates between large farms, making it possible for agricultural equipment standing idle on a certain farm to be temporarily leased to other farmers. The same is happening with machines for forestry, cranes, and equipment for road construction.

Robben found an opportunity to look beyond an apparent need of companies (buying equipment) to a much more fundamental need (being able to use equipment now and then). All he had to do was transition from selling products to delivering services. That freed him from the economic necessity to sell as much as possible, and it gave him the opportunity to contribute to fewer products in a way that was feasible from a business economics viewpoint. Floow2 is doing great, and thanks to this success, Robben contributes in two ways: to ecological and economic sustainability.

The achievement

You think and act in an integrated, chain-oriented, or even circular way.

This means:

- You deliver services, products, or processes. You describe how they are a part of a larger whole, e.g. of a chain or a life cycle in which many others, perhaps in different companies or countries, are working – before or after you – in the chain.

- Your activities may concern the life cycle of an industrial product, a human being, an animal, a natural habitat, a company, a community, or a country, etc. You may, for example, think of your suppliers and your customers.

- You map the consequences for sustainable development of these services, products, or processes, and you relate them to the total of the consequences of the entire chain or life cycle.

- You cooperate on improvement of these consequences with others who control or influence other parts of the chain.

- You design entirely new ways to fulfill the same functions and needs, and you conclude whether they are better than the existing ones considering sustainable development.

The transition from products to services can be seen in many fields at the moment. Take for instance “pay per lux,” a principle that was developed by Philips in collaboration with architect Thomas Rau. According to this principle, as a company, you don’t buy lamps but rather light. (Hence the name: “lux” is a measure for luminance or brightness.) That is to say, Philips designs the illumination scheme in the laboratories and offices of a customer based on the customer’s needs. Philips installs the armatures and lamps. Philips also pays for the electricity, replaces failing lamps, and adapts the lighting when the company changes. In other words, Philips is no longer a product seller but a service provider. There are many advantages. The customer, a company paying “per lux,” doesn’t have to take care of the lighting anymore since the service provider guarantees that everything works. In the past, some people used to say that light bulbs were produced in such a way that they would fail sooner rather than later (planned obsolescence); otherwise, the light bulb industry would not make enough money. Well, with the new approach, planned obsolescence is unthinkable because if the lights don’t last, the only one suffering is the provider itself. The provider also has an advantage: instead of a one-time contract while selling lamps, the provider now establishes an ongoing connection with customers, who will stay as long as they are satisfied.

We’re talking about a true transition here. If many goods are delivered in this way, not through sales but as rent or lease, with a maintenance obligation attached, the entire economy will change, even for ordinary household and lawn service clients. Try to remember the last time your washing machine broke down. Did you have a repairperson or a new machine in the house on the same or even the following day? If you did, maybe you were lucky. Probably you didn’t. However, if instead of buying a washing machine you had acquired a laundry contract, it would be in the immediate interest of the provider to replace the machine soon – and with a darn good model that is – since the provider has to pay a penalty for every day on which you cannot do laundry. When this principle is also applied to cars (as it has become quite customary), bicycles, kitchen equipment, TV’s, computers, printers, haymakers, threshers, printing presses, and folding machines, the economic and societal impacts are huge.

The nice thing is that I am not making this up. Many experts expect that this is all going to happen, or rather, it is already going on at full speed. We call it “the circular economy.” If you are not yet familiar with the concept, google it. You will be amazed.

The consequences for sustainability are great because the producers of the goods remain their owners. You don’t have to discuss deposits or take-back obligations because the taking back part is woven into the system. This “design for disassembly” method automatically convinces companies to design products in a manner that at their end-of-life point, when the devices are worn or obsolete, they can easily be taken apart. This makes it possible to reuse certain components or to recycle the material (see the product designer in Chapter 11). Closing the loop has become inevitable, and you automatically arrive at C2C, cradle to cradle!

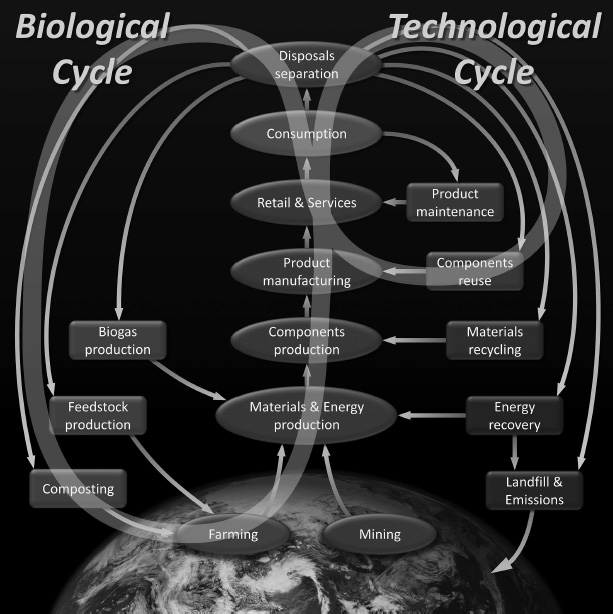

Besides this “technological cycle,” there is the “biological cycle,” in which the resources with which the technological cycle starts are derived from nature and in which, at the end of the life of a product, its waste materials are returned to nature in such a way that nature is not harmed. Together, the two cycles form a kind of figure “8.” You can see this “8” in Figure 6.2, lying on its side. The figure is derived from the second edition of my university textbook Fundamentals of Sustainable Development, (Routledge, 2017). In that book, you can find many more theoretical details about the circular economy.

In principle, this circularity idea is all highly logical and easy. In reality, it becomes more complicated when the chain of involved companies and customers is long and complex. When you are dealing with resources that are harvested or mined somewhere in the world, shipped to a broker, then combined into components consisting of several materials that are put together to form complex devices, etc., it can be very difficult to close the cycles. It will only be possible if the various links in the chain cooperate closely according to the principles of “integral chain management.” Fortunately, there exist thousands of examples to document the success of this method. As a percentage of the worldwide economy, the circular economy is growing at an explosive rate, and within a decade it will have gained critical mass.

Wonderful, beautiful! But what about the traditional service providers, for example, in healthcare? Well, in those fields, it is also possible to talk about an integral approach if caregivers cooperate with each other to provide suitable services, not to a knee or kidney, but to a human being. Moreover, if teachers and instructors of primary, secondary, and higher education start coordinating their work with institutions for lifelong learning, an integrated, chain-oriented, or even circular approach is born – aimed not at the lifecycle of products but of people. Cradle to cradle is not a proper term here, unless you consider the beds in the homes for the elderly a kind of cradle. In a figurative sense, the term does fit: people who reach old age have gone from intensive care (as a baby) to independency (as an adult) back again to intensive care (as an elderly person). Cycle closed.