Chapter thirteen

All the competences of the rainbow

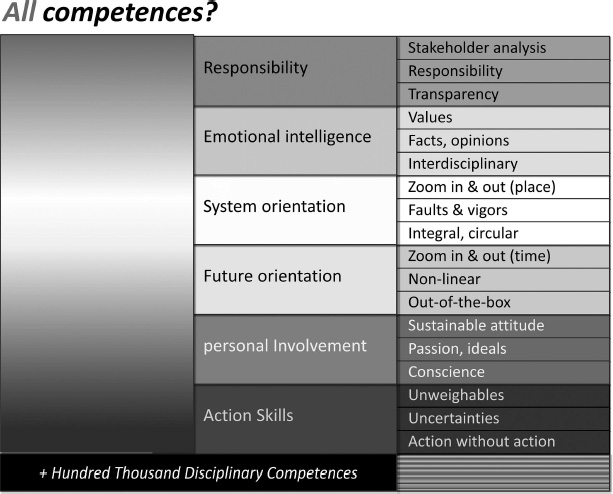

That’s it! The set of sustainability competences is complete. Chapter 11 presents a series of examples of specific competences for certain disciplines and professions. In the even-numbered chapters, 2 to 12, you can find all general competences.

All competences?

That is quite a claim, one I can never fulfill. Surely there will be people – you may be one of them – who, immediately after I make such an ambitious claim, will prove my mistake by mentioning a competence missing from my set. How about ethical consciousness, inspiration, leadership, or – if you are Christian – stewardship? In other words, how complete is this book anyway?

You see, competences are like colors; there exist an infinite number of them. If I mentioned a long series of colors and then claimed I had listed all of them, it would not be very hard to point out shades I had missed. There would be every chance that I didn’t include Bulgarian rose, Vegas gold, or Harvard crimson, eggplant, mint, or vanilla. Perhaps I failed to mention a nameless color that is indicated by its RGB values (red-green-blue), each expressed as a number between 0 and 65,535: this offers a variation of more than 280 million shades. That’s a lot, but it is nothing compared to the infinity of all colors. No, an enumeration of colors can never be complete.

The same applies to competences for sustainability. Whoever wants to will be able to express hundreds of them in the English language, and if you think that is still not enough, you can make up your own new words or borrow them from other languages. In short, the quest for completion is at best a hopeless effort and at worst a desperate exercise.

To deal with the enormous variety of colors, people have chosen to give names to a limited number of main colors and to consider the rest as mixtures, blends, or combinations of them. Since this has been done independently throughout many eras and in different cultures, it has rendered a fascinating diversity. Western culture traditionally distinguishes seven colors of the rainbow, plus black and white. In total, this makes a set of nine:

- Red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet, black, white

However, the Candoshi, a Peruvian tribe, distinguish only eight basic colors:

- Chobiapi, ptsiyaro, kamachpa, kavabana, tarika, kantsirpi, ponzani, borshi

It is not easy to translate them into English, but if you try, you get something like: red, yellow, bright green, greenish blue, purple, black, pale & grey, white.

The Kwerba, a tribe in Irian Jaya, Indonesia, know even fewer, namely four colors:

- Asiram, nokonum, kainanesesenum, icem

In English, this is roughly equal to red, yellow, green & blue & black, white.

You’re probably thinking: that’s rather primitive, only four colors? Well, my hypermodern laser printer does not possess many more, as it is a five-color printer:

- Magenta, yellow, cyan, black, white

For four of those colors, my printer has separate toner cassettes. The fifth color, white, is produced cleverly by not using each of those four toners simultaneously. How could the Kwerba be primitive? They are hardly second to a printer from the twenty-first century!

Why are there such huge differences between color schemes? Because every scheme you design will always be a simplification of reality. What you do is cut a continuous color spectrum into a finite set of separate colors. Actually, this is simply wrong, but what are you going to do? If you don’t wish to make this mistake, you can never define a color, and so we cut the rainbow into pieces: nine in Europe and North America (if you include black and white), eight with the Candoshi, four with the Kwerba, and all kinds of numbers with hundreds of different cultures.

This dividing of a continuous spectrum into a finite set of separate elements is something we do all the time, in every area. Do you want some examples from management science?

9 is the number of criteria of the EFQM Excellence Model for quality management:

- leadership, strategy, people, . . .

8 is the number of fields in Leary’s Rose:

- leading, helping, co-operative, . . .

7 habits are what highly effective people possess, according to Stephen Covey:

- proactive, begin with the end in mind, first things first, . . .

6 M’s are basic to the Six Sigma method for quality management:

- machines, methods, materials, . . .

5 layers together form the hierarchy of Maslow, a model for the needs and motivations of people:

- physiological needs, safety, social needs, . . .

4 steps are what Deming’s control cycle consists of:

- plan, do, check, act

3 is the number of elements in the Triple P of sustainable development:

- people, planet, profit

2 basic principles exist according to traditional Chinese philosophy:

- yang, yin

1 is the number of universes we live in:

- reality

Do you really think there are cosmic laws prescribing that a quality cycle consists of precisely four steps as Deming proposed? Of course not, and no doubt Deming realized that too. Or do you believe, as Covey taught us, that effective leaders possess exactly seven habits? Covey himself does not think so since he “discovered” an eighth habit a few years later:

- find your voice, in other words: inspire others

What all of these designers of the above models and systems have done is split reality into parts. While doing this, they corrupt reality, but that is all right as it provides us with methods to deal with reality effectively.

Mathematicians speak of a “cover.” The nine criteria of the EFQM model “cover” the wide area of quality management, roughly equal to the way in which a window screen covers an open window: hermetically closed for mosquitoes and other bugs and thus effective, but not 100% closed, therefore allowing fresh air to enter.

In the same way, the sustainability competences of this book cover the wide range of competences of a sustainable professional. My spectrum (see Figure 13.1) includes:

- responsibility, emotional intelligence, systems orientation. . .

This is not airtight, but it is effective. If you mention competences that are not literally there, they probably present variations or combinations of competences discussed in the book. Let me illustrate this with the cases I have already cited.

Are you looking for ethical awareness? Go to the section on Conscience in Chapter 10. Do you want to find the concept of inspiration? Have a look at Passion, dreams and ideals, also in Chapter 10. Aside from that, turn to Innovative, creative, out of the box in Chapter 8. You are interested in stewardship? Search for Responsibility in Chapter 2, and you will find related information.

Concerning leadership, I consider this concept to be of a different nature, not so much a competence but rather a competence level, so you can find it in Chapter 7, where varying degrees of leadership are explained, ranging from Apprentice (developing) to Master (advanced).

All in all this means, in my opinion, that the “rainbow” of sustainability competences in this book is complete, not in the sense of “airtight,” but certainly in the sense of a “cover.” Nevertheless, it could be possible that some essential competences for sustainability are truly missing from my framework. Personally, I don’t expect this to be the case, but one cannot be sure. So, who knows – maybe some interesting discussions lie ahead!