Organizational Culture in Higher Education

Rana Zeine, Michael Hamlet, Patrick Blessinger, and Cheryl Boglarsky

The organizational culture of academic higher educational institutions was analyzed using the Human Synergistics International (HSI) Organizational Culture Inventory (OCI) Survey. Cultural norms characteristic of Passive/Defensive and Aggressive/Defensive behavioral styles were overrepresented, while those characteristic of constructive styles were underrepresented, as compared to ideal profiles. The results reflect predominance of task-centered over people-centered organizational orientations and of lower-order (security) over higher-order (satisfaction) needs. Both current and ideal profiles were derived from the responses of higher education faculty and administrators who are active at nonprofit or for-profit organizations worldwide. Targets for cultural change were identified, and recommendations were developed to assist higher education institutions to approach their ideal organizational cultures.

Organizational culture in higher educational institutions (HEds) can be examined with regards to behavioral norms that have been extensively studied in the context of guiding organizational change in the corporate world. HEds are social sector organizations that differ in purpose and performance measures from business corporations.1 Because the purpose of social sector organizations is to meet social objectives, human needs, and national and global priorities, the people affiliated with them are ambitious first and foremost for the causes, the movements, the missions, the work—not themselves—and they have the will to do whatever it takes to make good on that ambition.2 HEds can be viewed as service providers fulfilling diverse customer needs.3 More complex dimensions apply in HEds because students can be viewed as products, customers, coworkers, and laborers simultaneously.4 Ideally, a culture of selflessness and excellence would be expected throughout the range of HEds, including those that rely heavily on business revenue streams, such as medical centers and for-profit colleges.5 Because financial incentives are weak in nonprofit organizations, their ability to generate funds to support their nonbusiness activities depends on effectively tapping into the idealistic passions of their deeply committed members and benefactors.6 In this chapter, we analyze the currently prevailing organizational culture and compare it to the ideal cultural profile for HEds as measured by the OCI.7

Perceptions of the work environment shape the organizational climate, which is a function of how employees experience their organizations.8 In the absence of active guidance aimed at nurturing healthy organizational dynamics, organizational cultures tend to default to rather constraining or low-performance states. For example, research indicates that people interacting on a task tend to voluntarily construct differences in hierarchy and contribute to their own disempowerment to maintain a stable hierarchical social order.9 Some studies have shown that, in contrast to higher-status schools, members of lower-status universities tend to accept the implications of the lowered status of their educational institution and do not take initiative to bolster it.10 People inside organizations who agree on organizational goals often hold differing views on how to accomplish shared objectives.11 Consequently, organizations can lose their vitality and begin to age as they remain unable or unwilling to evolve and change.12 Preliminary studies have highlighted the importance of exploring the complex barriers to cultural renewal in academic institutions in order to identify appropriate targets and develop suitable mechanisms for cultural change.13 Such studies explain that “culture forms the superglue that bonds an organization, unites people, and helps an enterprise accomplish desired ends.”14 However, “some argue that organizations have cultures, others insist that organizations are cultures.”15 Organizational culture has been defined as the following:

A pattern of shared basic assumptions that a group learned as it solved its problems of external adaptation and integration that has worked well enough to be considered valid and therefore to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think and feel in relation to those problems.16

Distinct but interdependent subcultures have been noted in HEds especially in regards to academic versus administrative divisions and for-profit/business/clinical versus nonprofit/research/educational organizations.17 A systematic analysis of current and ideal organizational cultures can inform HEds professionals on specific changes that would help them meet and exceed expectations.18

The OCI is a quantitative instrument that measures 12 sets of behavioral norms associated with 3 general types of organizational cultures: Constructive, Passive/Defensive, and Aggressive/Defensive.19 It focuses on 12 behavioral patterns that members believe are required to “fit in” and “meet expectations” within their organization.20 Descriptions of the 12 styles measured by the OCI are provided in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1. Descriptions of the 12 Styles Measured by the Organizational Culture Inventory® (and Sample Items)

Constructive cultures encourage members to interact with people and approach tasks in ways that will help them to meet their higher-order satisfaction needs for affiliation, esteem, and self-actualization:

(11:00) An Achievement culture characterizes organizations that do things well and value members who set and accomplish their own goals. Members are expected to set challenging but realistic goals, establish plans to reach these goals, and pursue them with enthusiasm. (Pursue a standard of excellence; openly show enthusiasm.) Achievement organizations are effective, problems are solved appropriately, clients and customers are served well, and the orientation of members, as well as the organization itself, is healthy.

(12:00) A Self-Actualizing culture characterizes organizations that value creativity, quality over quantity, and both task accomplishment and individual growth. Members are encouraged to gain enjoyment from their work, develop themselves, and take on new and interesting activities. (Think in unique and independent ways; do even simple tasks well.) While self-actualizing organizations can be somewhat difficult to understand and control, they tend to be innovative, offer high-quality products or services, and attract and develop outstanding employees.

(1:00) A Humanistic-Encouraging culture characterizes organizations that are managed in a participative and person-centered way. Members are expected to be supportive, constructive, and open to influence in their dealings with one another. (Help others to grow and develop; take time with people.) A humanistic culture leads to effective organizational performance by providing for the growth and active involvement of members who, in turn, report high satisfaction with and commitment to the organization.

(2:00) An Affiliative culture characterizes organizations that place a high priority on constructive interpersonal relationships. Members are expected to be friendly, open, and sensitive to the satisfaction of their work group. (Deal with others in a friendly, pleasant way; share feelings and thoughts.) An affiliative culture can enhance organizational performance by promoting open communication, good cooperation, and the effective coordination of activities. Members are loyal to their work groups and feel they “fit in” comfortably.

Passive/Defensive cultures are those in which members believe they must interact with people in ways that will not threaten their own security:

(3:00) An Approval culture describes organizations in which conflicts are avoided and interpersonal relationships are pleasant—at least superficially. Members feel that they should agree with, gain the approval of, and be liked by others. (Go along with others; be liked by everyone.) This work environment can potentially limit organizational effectiveness by minimizing constructive “differing” and inhibiting the expression of ideas and opinions.

(4:00) A Conventional culture is descriptive of organizations that are conservative, traditional, and bureaucratically controlled. Members are expected to conform, follow the rules, and make a good impression. (Always follow policies; fit into the mold.) Too conventional a culture can interfere with effectiveness by suppressing innovation and preventing the organization from adapting to changes in its environment.

(5:00) A Dependent culture is descriptive of organizations that are hierarchically controlled, are nonparticipative, and do not empower their members. Centralized decision making in such organizations leads members to do only what they are told and to clear all decisions with superiors. (Please those in positions of authority; do what is expected.) Poor performance results from the lack of individual initiative, spontaneity, flexibility, and timely decision making.

(6:00) An Avoidance culture characterizes organizations that fail to reward success but nevertheless punish mistakes. This negative reward system leads members to shift responsibilities to others and avoid any possibility of being blamed for a mistake. (Wait for others to act first; take few chances.) The survival of this type of organization is in question since members are unwilling to make decisions, take action, or accept risks.

Aggressive/Defensive cultures expect members to approach tasks in forceful ways to protect their status and security:

(7:00) An Oppositional culture describes organizations in which confrontation prevails and negativism is rewarded. Members gain status and influence by being critical and thus are reinforced to oppose the ideas of others (point out flaws; be hard to impress) and to make safe (but ineffectual) decisions. While some questioning is functional, a highly oppositional culture can lead to unnecessary conflict, poor group problem solving, and watered-down solutions to problems.

(8:00) A Power culture is descriptive of nonparticipative organizations structured on the basis of the authority inherent in members’ positions. Members believe they will be rewarded for taking charge and controlling subordinates and for being responsive to the demands of superiors. (Build up one’s power base; demand loyalty.) Power-oriented organizations are less effective than their members might think; subordinates resist this type of control, hold back information, and reduce their contributions to the minimal acceptable level.

(9:00) A Competitive culture is one in which winning is valued and members are rewarded for outperforming one another. Members operate in a win-lose framework and believe they must work against (rather than with) their peers to be noticed. (Turn the job into a contest; never appear to lose.) An overly competitive culture can inhibit effectiveness by reducing cooperation and promoting unrealistic standards of performance that are either too high or too low.

(10:00) A Perfectionistic culture characterizes organizations in which perfectionism, persistence, and hard work are valued. Members feel they must avoid any mistakes, keep track of everything, and work long hours to attain narrowly defined objectives. (Do things perfectly; keep on top of everything.) While some amount of this orientation might be useful, too much emphasis on perfectionism can lead members to lose sight of the goal, get lost in detail, and develop symptoms of strain.

Note: From Organizational Culture Inventory by Robert A. Cooke and J. Clayton Lafferty, 1987, Plymouth, MI: Human Synergistics International. Copyright © 1987, 2011 by Human Synergistics, Inc. Reproduced by permission. The OCI style descriptions and items may not be reproduced without the express and written permission of Human Synergistics.

In higher education, teaching hospitals can also be identified as “high reliability” organizations due to the life-and-death nature of health care services. Some institutions, such as the military and nuclear power plants, are considered high reliability organizations requiring very high fidelity to a chain of command, and strict adherence to protocols.21 Although behavioral norms from the Aggressive/Defensive and Passive/Defensive clusters may be highly represented, studies have shown that Constructive norms are desired and important for the success of such organizations because they help people to understand the reasons why orders need to be followed and the benefits of faithfully implementing best practices in performing critical duties.22

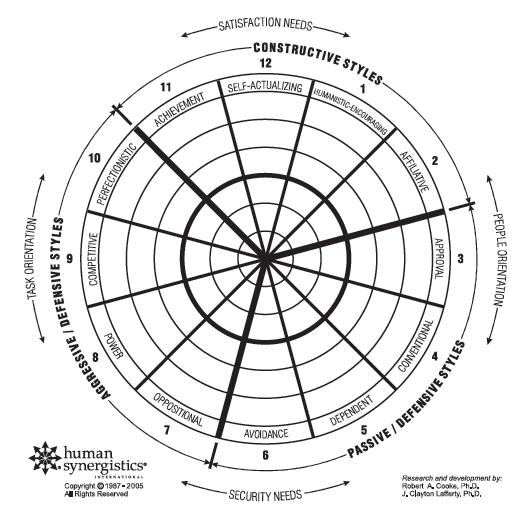

Figure 3.1. Organizational Culture Inventory® circumplex.

Note: Research and development by Robert A. Cooke, PhD, and J. Clayton Lafferty, PhD. Copyright © 1973–2011 by Human Synergistics International. All rights reserved.

Methods

Participants from higher education institutions completed Human Synergistics OCI and OCI-Ideal surveys (web-based version). The OCI measures the behavioral norms and expectations members understand are expected of them to fit in and meet expectations in their current position at their organization or the current state. It also measures outcomes associated with organizational culture (e.g., intention to stay, satisfaction, and customer service orientation) that provide insights into the need for cultural change.23 A parallel form of the inventory, the OCI-Ideal, asks the members to indicate the extent to which the behavioral norms and expectations should be expected in order to maximize their organization’s effectiveness. The results of the OCI-Ideal are the desired state and can be seen as a cultural benchmark.

Respondents’ OCI and OCI-Ideal unadjusted (or raw) scores were pooled and converted to percentile scores that were plotted on an OCI circumplex shown in Figure 3.1. The OCI circumplex compares respondents’ organization’s scores along the 12 cultural norms to the scores of 921 organizational subunits (e.g., departments and divisions of other organizations). The bold center ring on the circumplex represents the 50th percentile. In general, scores falling below the 50th percentile are low relative to other organizations, and scores that fall above the 50th percentile are high relative to other organizations.24

Norms that reflect expectations for people-oriented behaviors are located on the right side of the circumplex, while task-oriented norms are on the left side. The norms toward the top reflect expectations for behaviors that are directed toward higher-order needs for satisfaction, and those toward the bottom reflect expectations that focus on meeting lower-order needs for security.25 By analyzing the gaps or discrepancies between the current and ideal culture profiles, the behavioral norms where there is the greatest need for change can be identified. These gaps were calculated by subtracting the ideal from the current percentile scores. Undesirable gap values were negative for Constructive norms (too low) and positive for Passive/Defensive and Aggressive/Defensive norms (too high).26

Results

Demographics of Respondent HEds Professionals

Demographics of the HEds professionals who participated in the study are presented in Table 3.2. Of the 63 who responded to the OCI survey, 33 responded to the OCI-Ideal survey. They represented faculty, directors, chairs, and deans at nonprofit and for-profit colleges and universities. The number of years spent at their current organizations ranged from less than 6 months to more than 15 years.

| Table 3.2. Demographics of Respondents | ||

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | OCI current | OCI ideal |

| (n = 63) | (n = 33) | |

| Age | ||

| 30–39 | 10% | 6% |

| 40–49 | 35% | 24% |

| 50–59 | 30% | 36% |

| 60 or over | 17% | 30% |

| nd* | 8% | 3% |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 43% | 45% |

| Male | 52% | 55% |

| nd* | 5% | — |

| Years with Organization | ||

| Less than 6 months | 5% | 6% |

| 6 months to 1 year | 3% | 0% |

| 1 to 2 years | 16% | 18% |

| 2 to 4 years | 17% | 24% |

| 4 to 6 years | 6% | 9% |

| 6 to 10 years | 13% | 18% |

| 10 to 15 years | 13% | 9% |

| More than 15 years | 22% | 15% |

| nd* | 5% | — |

| Organization Level | ||

| Faculty/Professor | 40% | 45% |

| Director | 24% | 12% |

| Department Chair | 6% | 6% |

| Associate Dean | 6% | 6% |

| Dean | 11% | 9% |

| Provost/Dean Academic Affairs | 2% | 3% |

| nd* | 11% | 18% |

| Education | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 2% | 3% |

| Master’s degree | 21% | 15% |

| Doctorate degree | 52% | 58% |

| MD | 2% | 3% |

| MD/PhD | 19% | 18% |

| Other | 2% | — |

| nd* | 3% | 3% |

| Institutional Type | ||

| For-profit; Public | 17% | 12% |

| For-profit; Private | 21% | 24% |

| Not-for-profit; Public | 38% | 33% |

| Not-for-profit; Private | 16% | 18% |

| nd* | 8% | 12% |

| Institutional Level | ||

| Associate’s College | 3% | 3% |

| Bachelor’s College | 6% | 6% |

| Master’s College/University | 35% | 36% |

| Doctorate-granting University | 46% | 48% |

| Special Focus Institution | 2% | — |

| nd* | 8% | 6% |

| *not determined | ||

Differences Between Current and Ideal HEds Organizational Culture Profiles

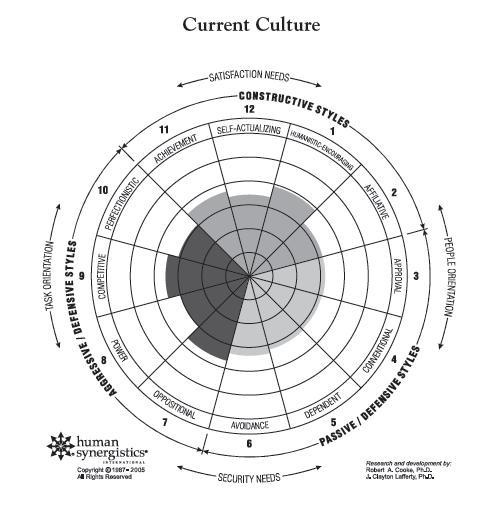

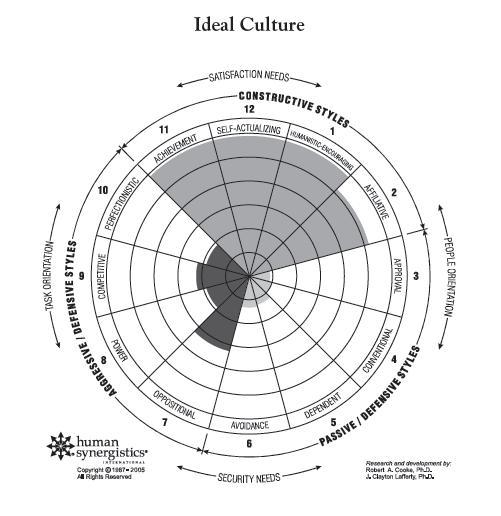

Undesirable gaps in percentile scores between current (Figure 3.2, top) and ideal (Figure 3.2, bottom) were found in all 12 styles on the HEds OCI profiles (Table 3.3). Extensions of the Constructive styles fell below the 73rd percentile in the current profile while rising above the 92nd percentile in the Ideal (Table 3.3). Passive/Defensive styles extended above 54% in the current profile while remaining less than 15% in the ideal (Table 3.3). The lowest gap between current and ideal was in the Oppositional style norms that extended to 67% in the current profile, only 10% higher than ideal (Table 3.3). This is consistent with cultural norm requirements of “high reliability” organizations.

Figure 3.2. Current versus ideal HEds OCI profiles.

Note: Research and Development by Robert A. Cooke, PhD, and J. Clayton Lafferty, PhD. Copyright © 1973–2011 by Human Synergistics International. All rights reserved.

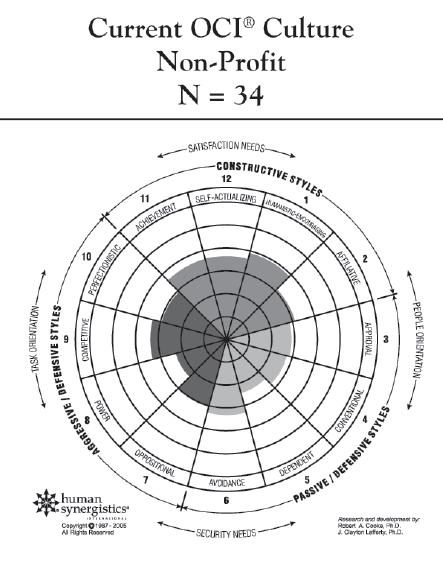

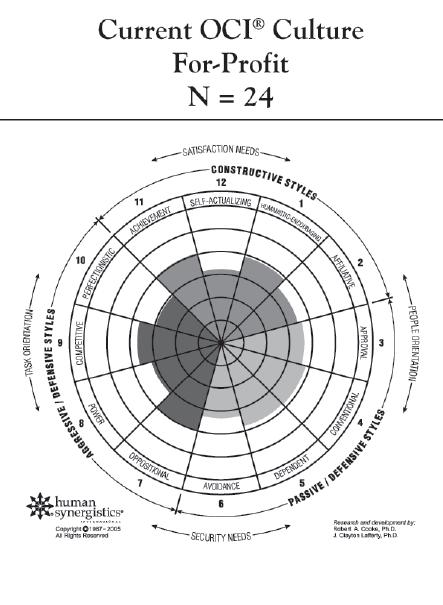

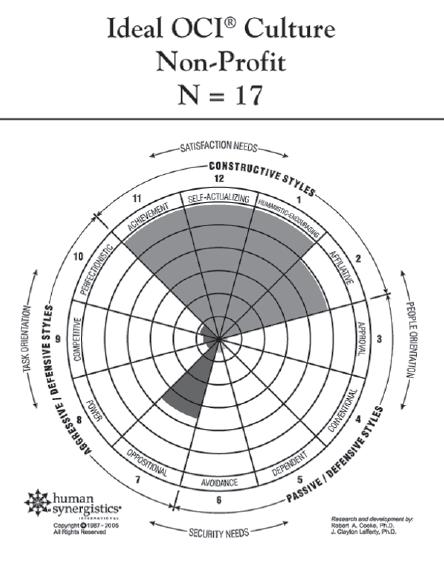

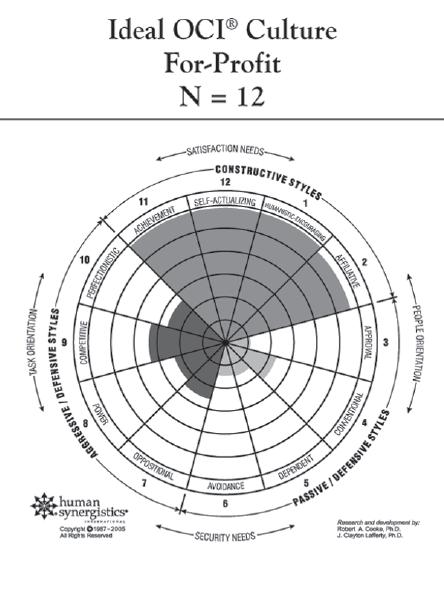

Figure 3.3. Nonprofit vs. for-profit HEds organizational culture profiles.

Note: Research and development by Robert A. Cooke, PhD, and J.Clayton Lafferty, PhD. Copyright © 1973–2011 by Human Synergistics International. All rights reserved.

Figure 3.3. (continued)

Differences Between Nonprofit and For-Profit HEds in Organizational Culture

As compared to the current Nonprofits OCI profile (Figure 3.3), the current For-Profit profile (Figure 3.3) had wider extensions along several of the Aggressive/Defensive and Passive/Defensive styles. As compared to the ideal Nonprofit profile (Figure 3.3), the ideal For-Profit profile (Figure 3.3) had a narrower extension on the Oppositional style but wider extensions on the seven remaining Defensive styles. The Constructive cluster extensions were similar in Nonprofit and For-Profit HEds (Figure 3.3).

| Table 3.3. Gap Analysis for HEds Organizational Cultural Styles | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentile score | ||||

| Style | Ideal | Current | Gap | Cluster |

| Humanistic-Encouraging | 98 | 73 | -25 | Constructive |

| Achievement | 98 | 67 | -31 | Constructive |

| Self-Actualizing | 98 | 61 | -37 | Constructive |

| Affiliative | 92 | 55 | -37 | Constructive |

| Oppositional | 57 | 67 | 10 | Aggressive/Defensive |

| Competitive | 31 | 63 | 32 | Aggressive/Defensive |

| Perfectionistic | 23 | 52 | 29 | Aggressive/Defensive |

| Power | 23 | 50 | 27 | Aggressive/Defensive |

| Avoidance | 15 | 59 | 44 | Passive/Defensive |

| Dependent | 14 | 55 | 41 | Passive/Defensive |

| Conventional | 10 | 54 | 44 | Passive/Defensive |

| Approval | 9 | 55 | 46 | Passive/Defensive |

| Note: OCI style names and descriptions from Robert A. Cooke and J. Clayton Lafferty, Organizational Culture Inventory, Human Synergistics International. Copyright © 1987–2011. All rights reserved. Adapted by permission. | ||||

Implications of the Cultural Gaps on Outcomes

People at HEds experience both the negative and positive consequences of their organization’s cultures. Comments from 35 respondents offered insightful suggestions for effecting change in higher education, calling for “systematic changes starting with mission/vision, hiring and reward systems.” One wrote, “Make everyone in the pipeline at educational institutions better educated in best-practices, more accountable for their outcomes and for meeting targets; and hold a higher standard for quality teaching and for grading students.” Others echoed “Emphasize independent, critical thinking, and place greater responsibility for adaptive learning on the student,” “Communicate initiatives timely and thoroughly.” The participants’ comments were harmonious and can be summed up as a call to promote “systems and processes that support: good governance; understanding stakeholders’ needs; strong culture of continuous improvement; organizational culture that values and respects individuals and promotes their learning and professional development; strong data-driven planning; organizational agility; integrity in word and deeds.”27

Quantitative analysis of the organizational outcomes revealed desirable gaps in several areas and undesirable gaps in others. Intention to stay, personal customer service, satisfaction, and personal recommendations of the HEd as a good place to work all fell well above the historical average, while organizational customer service, role clarity, and role conflict fell well below the historical average.

Both the qualitative and quantitative cultural outcome measures indicate a need for changes in structures, systems, technologies, and skills and qualities of the HEds. Respondents urged, “Focus on students and their needs. Ask yourself, how can creating a great experience (learning and otherwise) make the student grow more? How does that student’s experience help our institution grow and become better?” Some were concerned that “higher education is no longer about the students, but about the business.”28 These comments highlight the importance for HEds to become more service oriented. Low scores along service quality measures indicate the need for the establishment of service-oriented procedures and norms; evaluation; and possible reengineering of core processes, customer-service training, and the revision of reward systems (to reinforce goal attainment).29

Recommendations for Leading Cultural Change

We recommend that both for-profit and nonprofit HEds implement strategies used by organizational leaders seeking to effect change:30

- Use belief systems (vision, mission, core values) and performance measures to strike an effective balance between creativity and control. Become living symbols of the newly minted organizational culture, and assist executives to fulfill this requirement by providing training and appropriate feedback systems.

- Plan for, create, and celebrate progress and work accomplishments.

- Enlist people who are highly talented, intelligent, energetic, tenacious, and committed to placing the interests of the organization above their own self-interests.

- Empower change enthusiasts with communication and consultation skills.

- Establish effective conflict resolution processes.

- Convey a sense of urgency by increasing awareness of the need for change.

- Identify, replace, or eliminate rules and policies (i.e., compensation, performance-appraisal systems, organizational priorities) that are incompatible with the new vision. Implement an open-door policy.

- Ensure inclusive involvement and participation in shaping the transformative process.

- Build trust by disseminating information to people in all roles and at all levels throughout the organization.

- Inspire imagination and creativity by safeguarding freedoms, encouraging risk taking, and protecting research time.

- Constantly search for newer and better ways to do everything.

- Develop a shared vision and ensure congruency of action.

- Support one another and work with others. Encourage open-mindedness, innovation, and problem solving.

Recommendations for Adopting and Adapting High Performance Practices

We recommend that both for-profit and nonprofit higher education institutions adopt Jeffrey Pfeffer’s31 seven practices of high performing corporations to their business and administrative divisions, while developing corresponding alternatives for their academic divisions:

- Employment security or employment opportunity alternatives (externships, internships, work-study, career development, and placement services)

- Selective hiring or selective admission alternatives

- Self-managed teams and decentralization of decision making or participative cultural alternatives (feedback, communication, consultation)

- Comparatively high compensation contingent on organizational performance or academic support alternatives (grants, fellowships, scholarships)

- Extensive training including leadership, management, and communication skills

- Reduced status distinctions and barriers

- Extensive sharing of financial and performance information throughout the organization

Recommendations: Reducing Defensive and Promoting Constructive Cultural Styles

Unresolved conflicts, demotivation, work avoidance, and high turnover are consequences of Passive/Defensive organizational cultures where conflicts are primarily resolved by either accommodation or withdrawal. Insecurity, disempowerment, disrespect, and punishment characterize Aggressive/Defensive cultures as they value confrontation, criticism, coercion, and overconfidence. By contrast, flexibility, consultation, knowledge, reason, and coordination are features of Constructive organizational cultures as they encourage communication, sharing, and cooperation with others.32

We recommend that both for-profit and nonprofit higher education institutions adopt the Human Synergistics International recommendations to cultivate Constructive norms within organizations at the member, unit, and organizational levels:

- Ensure that all members are given the opportunity to work to their full potential

- Balance expectations for taking initiative and thinking independently with those for consensus and power sharing

- Expect participation without domination

- Elicit unique perspectives and concerns while working toward agreement

- Value quality over quantity

- Value creativity over conformity

- Judge effectiveness at the system level rather than the component level

- Practice empowerment and transformational leadership that are prescriptive (guide and direct) rather than restrictive (constrain and prohibit) practices

- Adopt approaches for continuous, system-wide improvements including problem solving, strategic planning, innovation, and benchmarking

- Inspire innovation by allowing people to express themselves, experiment, and learn from mistakes

- Increase accomplishments by encouraging people to set challenging goals and by providing them with necessary resources

- Cultivate mentors by investing in training and development and by providing opportunities for expansion

- Enhance cooperation by letting people communicate, get to know one another, contribute, and share ideas

- Inculcate humanistic values of mutual encouragement and support

- Develop organizational mechanisms to collect and respond to feedback and implement good suggestions

- Remember that education institutions are learning organizations that emphasize creativity, individual development, and systems thinking

- Treat all members of the organization with respect and dignity

- Provide equitable pathways for advancement (or alternative opportunities for placement elsewhere)

Conclusion

This chapter profiles organizational culture in higher education institutions. Twelve cultural styles are analyzed, and differences between current and ideal behavioral norms are identified as targets for organizational change in nonprofit and for-profit colleges and universities. Recommendations are presented to assist professionals in their efforts to implement strategies that would reduce the intensity of eight Defensive patterns and promote four prescribed Constructive cultural styles. Further studies are warranted to examine subgroup and subdivisional cultures within educational institutions.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the distinguished respondents for their participation and input. We are grateful to Sarah Peterson of Human Synergistics, Inc., for expert assistance