Administrative and Academic Structures

For-Profit and Not-for-Profit

Andrew Carpenter and Craig N. Bach

In the United States, for-profit institutions of higher learning are typically led by highly skilled business professionals with limited academic expertise; not-for-profit institutions are usually governed by highly successful academics who occupy positions of administrative power but have little or no training in strategic management. The former are more effective at managing an institution to meet changing landscapes but rarely have the educational experience or insights to build and sustain strong academic programs. The latter have greater capacity to build strong academic programs but often lack the managerial excellence to support institutional foresight and agile responsiveness to change. The authors present a conceptual road map of hybrid institutional structures better able to meet the changing needs of higher education in the 21st century.

The United States is at a turning point. Over the coming decades, the global position and prosperity of the country will be challenged in new ways that are more significant than we have experienced in the recent past. Education will be a primary driver of our success in meeting these challenges—as go our systems of education, so goes the country. A set of significant challenges is present as we seek to meet our nation’s educational and training goals in the coming decades; how we approach these issues will have significant impacts on the economic, political, and global position of the country. One vital task with respect to postsecondary education is investigating the possibilities for structuring an educational system—and strategically managing institutions of higher learning—to (1) provide greater access, (2) graduate more students who can contribute to the country’s intellectual and economic prosperity, and (3) demonstrate more accurately the achievement of those graduates.

The authors of this chapter contend that to achieve these goals there needs to be a more productive conversation between for-profits and traditional models of higher education. In fact, traditional distinctions based on financial structures are too broad and gloss over meaningful distinctions based on institutional types and hierarchies, relationships among constituents, the role of the faculty, and students’ experience and expectations, among others. What is needed is a robust conversation that challenges almost all of the assumptions that seem to distinguish institution types.

In recent years, the growth of for-profit educational ventures has opened up higher education to hundreds of thousands of students.1 However, along with the successes of many of these institutions has come increasingly more urgent calls for oversight, an increase in federal investigations, and a growing number of lawsuits focused on their business practices. These activities have provided traditional institutions with “evidence” to inappropriately, and too easily, close off conversations about the value of the structures and practices of for-profit institutions both for the nation and for their own advancement. At the same time, traditional institutions are in no position to rest on their laurels. Rising tuition, unacceptably low graduation rates, destructive engagement with ranking systems that are misaligned with broader national education goals, and an inability to demonstrate learning in meaningful ways provide a strong argument that many traditional not-for-profit institutions of higher learning are not structured to meet the nation’s education goals in the coming years.

For-profit and not-for-profit models of higher education are dealing with a range of similar issues. The following is the core set of issues that will be discussed throughout the chapter.

Access and Opportunity

Access in and of itself is not sufficient to be considered an opportunity; opportunity is driven by both access and the likelihood of success. As access is opened to nontraditional and underserved students, new methods of determining risk and focusing interventions need to be established, and as student populations change the same institutional structures that worked 50 years ago do not provide good solutions to current problems.

Indeed—and as contemporary critics of for-profit institutions emphasize—without the likelihood of student success, access can be devastating because it leads not to life- and society-transforming educational growth but rather to such ills as increased debt without credit or learning, wasted time and resources, and wasted tax dollars. But it is also no solution to tie access directly to likelihood of success by providing access only to those most capable of succeeding. What is required is a more nuanced model that seeks to better understand significant learner differences and how to support their success.

Financing and Crediting Higher Education

Continuing to increase tuition and the percentage of international and out-of-state students (in order to raise greater revenues) in the face of budget cuts and shrinking endowments is not a sustainable model for financing higher education. It also purposefully ignores the educational needs and financial resources of most of our citizens and often reduces underrepresented minority access.2 How we structure and place learning, and all the things that go into supporting that learning in ways that are affordable are key issues that need new answers. In addition, the current difficulty students have in transferring earned credits, the institution-dependent value of earned credits, the lack of transparency and commensurability of earned credits, and the lack of robust systems to acknowledge learning gained through lived experience each detracts from the progressive and inspiring mission of advancing learning across new populations.

Measuring the Quality of Higher Education: Learning

The main purpose of an institution of higher education, along with the generation of new knowledge, is the transmission of knowledge and skills. Learning is at the core of all schools, colleges, and universities. The obvious point only accentuates the inability of these institutions to meaningfully distinguish learners, align learners to instructional interventions and experiences, and measure the learning achievement of students in ways that inform both the students and the decisions made to support students. A robust conversation across institution types is in order to better address the assessment challenge.

Measuring the Quality of Higher Education: Accountability

The calls for accountability in higher education that institutions should be expected to define and elaborate on the value they provide students and society run across all sectors of higher education. Given the relatively recent (compared to more traditional models) development of for-profit institutions, the expectations of accountability often run a bit higher for that sector. (Of course, some institutions’ recent behaviors also add to this increased focus.) In fact, many traditional institutions find themselves strongly supporting new rules or compliance regimens based on some specific institutional behavior only to find a broadly worded and ill-conceived version of it applying to them as well. The case is even worse when the new rule is antithetical to the educational goals of the country, for example, recently passed program integrity rules.3 Additionally, much of what goes for “quality” in higher education is advanced under obtuse ranking systems that neither reflect the country’s educational goals nor focus on what many institutions, students, parents, and taxpayers value the most (e.g., affordable, high-quality education, or the likelihood of obtaining a job). Greater reflection across institution types and how we think about quality will lead us to a more creative and reasonable conversation.4

The means by which we address these issues will benefit by improving the conversations between for-profit, public, and private institutions. The rest of this chapter is devoted to presenting several meaningful ways to begin that conversation and to explicating further why that effort is a worthy one.

Organizational Structures and Values: Four Key Distinctions

Four key distinctions support a nuanced comparative assessment of the diverse organizational structures of for-profit and not-for-profit institutions of higher learning: the distinction between tightly versus loosely coupled organizations, the distinction between siloed and networked organizational structures, the distinction between mission- and profit-driven organizational cultures, and differences between incentive and accountability systems.

Below we provide a high-level overview of these four evaluative dimensions with an eye to articulating their most important application to the strategic management of institutions of higher learning. In addition to orienting readers to these crucial evaluative dimensions, we also demonstrate that evaluating institutions of higher learning along each of these four dimensions makes visible variations and hybrid structures that conventional accounts of not-for-profit and for-profit institutions of higher learning pass over.

Tightly Versus Loosely Coupled Organizations

From the perspective of strategic management, what matters most for this evaluative dimension is the level of central administrative power: A tightly coupled organization is more centralized with a stronger hierarchical structure, whereas a loosely coupled organization features more decentralized decision making and weaker centralized managerial oversight. The strategic advantage belongs to those organizations that avoid both extremes: Neither extremely tightly coupled organizational structures nor extremely loosely coupled structures are well positioned to manage their resources in ways that promote organizational agility, responsiveness to change, and foresight to plan proactively. On the one hand, and as one of the authors has demonstrated elsewhere,5 an extremely tightly focused organizational structure forgoes opportunities for broad-based involvement in decision making, and a strongly hierarchical structure may also make it more difficult to build and apply social capital to sustain a learning-centered organizational culture that respects people within the organization. On the other hand, an extremely loosely coupled organizational structure fosters inefficient decision making that is uncoordinated and so vulnerable to redundancy, promoting inconsistent use of resources or moving forward actions that are incompatible with the organization’s strategic values and objectives.

With respect to institutions of higher education, the conventional stereotype is generally correct: For-profit institutions tend to be more tightly coupled, not-for-profit institutions less so. By itself, however, this fact is of little strategic managerial importance because the considerable variations among institutions of both types matter more. So for example, a loosely coupled structure that might be expected to lead to conflicted or slow decision making due to lack of centralized decision making can serve to sustain departmental or other local administrative units that possess agile and effective systems for localized adaptations to student and other stakeholder needs. Conversely, a tightly coupled structure that might be expected to ignore the needs of individual stakeholders at the departmental level may develop systems for fact-based information gathering and analysis that provides centralized managers with granular data that allows them to understand and coordinate the needs of all local organizational units.

What is fundamentally important is that strategically minded managers of institutions of higher learning seek out opportunities to lead their organizations away from destructive extremes of either too tightly or too loosely coupled organizational structures. On the one hand, leaders within the centralized management of a relatively tightly coupled institution of higher learning should seek out opportunities to promote collaboration in ways that lead to the generation of social capital and respect and promote the development of its faculty and staff. On the other hand, leaders within relatively loosely coupled institutions should seek out opportunities collaboratively to build systems of strategic planning and data analysis that promote coordinated and consistent decision making throughout the institution. Neither the for-profit nor the not-for-profit organizational structures are inherently destined or precluded from striking the appropriate balance; in both cases, however, leaders have significant opportunities to exert strategic vision that avoids the excesses and maximizes the chances of achieving the benefits described previously.

Siloed Versus Networked Organizational Structures

Peter Drucker6 famously argued that business organizations’ adopting decentralized, team-based, and distributed structures can promote organizational agility that supports flexible and efficient responses to changing business needs. Such networked structures, Drucker maintained, are marked by increased informal communication throughout an organization that was more extensive and more interactive than more formal communication disseminated through a hierarchy and within siloed organizational divisions.

From the perspective of strategic higher-education management, promoting effective lateral, interunit interaction that maximizes the benefits of these types of interactions can produce more effective collaboration and coordination, increased generation of social capital, and new opportunities for organizational learning. Identifying and addressing problematic structural silos is equally important for the strategic management of institutions of higher learning—all institutions of higher learning. Consider the problem often faced by traditional institutions of having multiple units having no idea what other units are doing or that so completely lack communication structures that the only way to move a message across the institution is to overcommunicate to each individual. Not-for-profit and for-profit institutions alike constitute complex organizations containing multiple systems and subsystems that can become siloed in a manner that diminishes an institution’s performance.

Incentives Versus Accountability Systems

From the standpoint of strategic management, one often observes tenuous relationships between the financial goals and the educational goals of institutions of higher learning. These goals are sometimes in conflict, and the key strategic managerial question is to identify how and when they can be aligned so that the imperative of meeting financial targets focuses energy and other resources that enhance the institutions’ ability to meet their learning goals.

In the contemporary environment of budget cuts, the prospect of such alignment may seem mythical. Moreover, in happier fiscal times the effort purposefully to craft such an alignment may seem unnecessary. However, there is a clear strategic path to follow: Strategically design a financial incentive structure that is systematically integrated with and supports a robust structure of accountability for meeting strategic goals, including educational goals. Major challenges to the credibility of for-profit education exist when financial incentives conflict with—or, in the worst cases, simply replace—accountability systems for educational quality and integrity. For example, incentivizing admission representatives based on the number of enrollments they secure, no matter how likely they are to retain, may help meet near-term financial goals but clearly can diminish the achievement of educational goals (e.g., retention and learning). Likewise, disconnects between the incentive and accountability systems at not-for-profit institutions can lead to poor strategic management that includes, in the worst cases, institutional neglect of its core academic mission.

Mission- Versus Profit-Driven Cultures

An institution that is dominated by a mission-driven culture typically evinces genuine concern for its mission and for its students’ and other stakeholders’ needs but may also lack the fiscal and managerial discipline necessary to live up to its values and aspirations. In addition, many traditional institutions could benefit by improving their abilities to strategically plan and assess their performance against a mission and build that process into their operations (e.g., not waiting until they prepare for an accreditation visit). By contrast, an institution where a profit-driven culture dominates may face intensive pressures to maximize financial results over the short term in ways that lead to continual deferral of long-term investments necessary for organizational and academic advancement; in the most egregious cases, short-term profitability maximization may cause an institution self-destructively to sacrifice its academic quality and integrity. Perhaps, here is where the two types (broadly speaking) of institutions differ and where the lessons that can be learned from each are most starkly highlighted. Mission-driven institutions often lack the managerial expertise of most successful for-profit institutions; for-profit institutions often focus too narrowly on short-term financial gains at the cost of educational and longer term goals.

From a strategic management perspective, the clear best case is when an organization possesses a well-defined academic mission and is managed so as to be able to reach profitability while executing that mission. This alignment of mission and profitability can only occur by happy accident within an organizational culture that is either heavily mission driven or profit driven. To secure this alignment purposefully, what is required is a hybrid organizational culture, and we maintain that there exists a compelling strategic management opportunity for institutional leaders to forge a culture that exploits both the managerial and data analytical talents of the highly skilled business professionals more commonly found in for-profit institution leadership and the educational experience and insights for building and advancing strong academic programs possessed by the highly successful academics that more frequently lead not-for-profit institutions of higher learning.

Faculty Roles and Composition

Even among not-for-profit institutions, faculty characteristics vary greatly among institution type: The most coveted characteristics of faculty differ significantly, say, at research-intensive doctoral universities, teaching-intensive liberal arts colleges, and teaching-intensive community colleges. By contrast, desired faculty characteristics in the for-profit sector are more uniform: Most for-profit institutions of higher learning rate faculty professional and career experience much higher than academic experience and credentials. In this section, we discuss how, on the one hand, for-profit institutions can secure significant benefits by valuing academic experience and credentials and, on the other, not-for-profit institutions can advance by adopting key elements of systems for assuring the quality of faculty instruction that have been developed at the best for-profit institutions. We also urge leaders of all institutions to do more to integrate adjunct and other nontenure-track faculty meaningfully into campus culture in general and more particularly into systems of shared governance.

The Rise of Adjunct Faculty and the Decline of the Tenure Track

Two important and well-documented trends among not-for-profit postsecondary institutions in the United States are increasing use of adjunct faculty and the concomitant decreasing importance of tenure-track faculty. In each of these cases, not-for-profit institutions are moving closer to practices embraced with great zeal within the for-profit postsecondary sector, where adjunct faculty are the norm and academic tenure is rejected even as an aspirational goal.7

With respect to strategic management, we see two important opportunities for developing a more productive conversation between for-profit and traditional models of higher education. First, we urge the leaders of for-profit institutions of higher learning to engage in dialogue with their counterparts at not-for-profit institutions about the benefits of recruiting more faculty members with stronger academic experience and credentials. Second, we urge the leaders of not-for-profit institutions to engage in dialogue with their peers in for-profit institutions about processes for ensuring academic quality, integrity, and community among adjunct and nontenure-track faculty. We see much value for strategic advancement and competitive advantage for those managers of for-profit institutions who can increase the level of academic engagement and expertise of their faculty through hiring more faculty members with stronger academic credentials and experience. Embracing this lesson requires shedding the bogus prejudice that academically well-credentialed faculty have little to contribute to the mission and advancement of for-profit institutions. Likewise, we see much potential advantage for those not-for-profit institutions that are able to design effective systems and processes that value adjunct faculty, integrate them into the academic life of their institution, and promote their professional development.8 Embracing this lesson requires shedding the prejudice that institutional reliance on adjunct faculty is inconsistent with sustaining and advancing academic quality and integrity. We submit, therefore, that the best not-for-profit institutions have much to teach about the value of strong academic credentials and experience, and the best for-profit institutions have much to teach about the effective use of adjunct faculty to advance institutions’ academic missions.9

Faculty Governance

With respect to faculty governance, we note only that each institution type has significant challenges to overcome: Whereas not-for-profit institutions typically possess elaborate systems of shared governance that frequently are moribund, a barrier to the advancement of for-profit institutions is the extremely limited—or even nonexistent—governance roles accorded to faculty. Here, too, the leaders of each institution type have important lessons to learn from their counterparts. Leaders of not-for-profit institutions can learn to improve the efficacy of governance by studying the best practices of their more entrepreneurial for-profit peers in designing efficient decision-making systems that make effective use of fact-based information gathering. At the same time, leaders of for-profit institutions can learn how to harness the wisdom of their faculty by taking seriously the value of shared governance and applying to their own institutions the best examples of effective shared governance provided by exemplary not-for-profit institutions. Here, too, significant competitive advantage will come to those leaders able to overcome the specious barriers that block effective dialogue of this sort.10

Supervision and Autonomy of Faculty

The final considerations we address about the faculty of not-for-profit and for-profit institutions of higher learning also involve a call for reasoned dialogue among what are too commonly and too easily framed as antagonistic and irreconcilable extremes. Here the key issues are the professional management and supervision of faculty and faculty autonomy and academic freedom. Our recommendation here is simple but unorthodox: Whereas it is commonly assumed that a high level of autonomy and low supervision is the only management structure that protects academic freedom, we maintain that professional supervision of faculty work can meet stakeholders’ legitimate need to hold faculty accountable for the quality of their work without abridging academic freedom.

Earlier we maintained that an obstreperous unwillingness to consider and apply the advantages of higher-quality academic credentials and engagements harms the long-term advancement of for-profit institutions of higher learning.11 Here we maintain, similarly, that an obstreperous unwillingness to consider and apply the advantages of higher-quality management skills and supervisory processes harms the long-term advancement of not-for-profit institutions of higher learning. Just as competitive advantage goes to those for-profit institutions whose leaders shed prejudice against quality academic credentials and experience, so, too, will competitive advantage be gained by those not-for-profit institutions that shed the prejudice against the use of effective management and supervisory techniques to assure and advance the quality of instruction and curriculum. In particular, not-for-profit institutions face a high hurdle: overcoming the self-interested objections of faculty that they are capable of producing quality work only if they are left alone to work without meaningful supervision from their department chairs or academic deans. Just as power centralized too narrowly in nonacademic decision makers constitutes a significant organizational weakness of many for-profit institutions, so, too, does the unrelenting attachment to perks and privileges by the decreasing and defensive population of tenured faculty constitute a serious organizational weakness at many not-for-profit colleges and universities.

Curricular Structures

A distinguishing hallmark of the curriculum at many for-profit institutions is a high degree of centralization. This characteristic can rankle those accustomed to the loosely coordinated, organically developed curricula found at many not-for-profit institutions. Often, an assumption that a centralized curriculum is synonymous with the use of canned courses leads to the perception that these curricular structures are a demeaning restriction of faculty autonomy and promote a destructive one-size-fits-all mentality that serves students poorly. However, many programs at traditional institutions are finding centralized curricula to be a viable solution.

Changing accountability expectations have led some educators to begin revisiting the efficacy of implementing a centralized curriculum and to think more carefully about what should be central in coordinated curricular efforts and about which contexts are most appropriate for such coordination. For example, programs that focus on a standards-based set of student-learning goals, or the achievement of other types of outcomes due to programmatic accreditation requirements, frequently confront the need to increase control over the consistency and structure of curricula in order to better measure and ensure student achievement. The level of curricular consistency and the means to ensure quality across a curriculum will depend heavily on disciplinary and institutional cultures: What works for an engineering program at an institution focused on applied learning is not likely to work well for a philosophy program at a small liberal arts college. However, the conversation between these two programs can be quite revealing and productive.

Many times the rules of engagement by which faculty develop and transmit a curriculum are implicit and organic, leaving the faculty and program administrators without important tools that can be used to better understand student learning, behavior (e.g., retention), and satisfaction. By having programs go through a process of mapping their curricula and discussing the ways faculty members and administrators ought to relate to one another in the transmission of knowledge to students, the implicit understandings underlying curricular development become explicit and intentional. In addition, as a secondary effect, faculty members come to see the manner in which they manage a curriculum and related issues (e.g., academic freedom, faculty autonomy, faculty satisfaction) that are discipline specific and not universal truths; the latter often frees them to explore new ways of organizing themselves around student learning.

The fact is that at every institution of higher education, there exists some level of coordinated or centralized curricular structures. Examples include a team-taught first-term calculus course with multiple sections taught by multiple instructors, a required first-year experience course, and a teacher education program tied across all courses to state standards built into the curriculum. By exploring the reasons why these efforts found coordinated solutions viable, and to what extent coordination is encouraged, interesting discussions around the applicability of these models to other instructional contexts are supported.

For-profit institutions that may have maintained heavily administrative, top-down, centralized curricular structures are exploring the benefits of greater faculty governance and autonomy. There is a range of models that can be used to develop a centralized curriculum that meets quality-assurance goals while at the same time promoting faculty engagement, creativity, and scholarship. The following are a few examples:

- Core and Elective Courses: A curriculum can be centralized around a small, core set of courses while allowing faculty members the autonomy to develop elective courses as they deem appropriate.

- Community Ownership: While individual faculty may not be able to make significant changes to a course or curriculum, these decisions may the responsibility of teams of faculty within a discipline. These teams can comprise full-time faculty, faculty members with a sufficiently long employment record at the institution, or all faculty members within a discipline. Using a consensus or majority model, they make all decisions about a curriculum.

- Fixed or Customizable Cuts: A curriculum can be structured to allow any faculty teaching a course to change a set percentage of a course or any noncore part of a course. For example, faculty may be asked to teach a course with a set of learning outcomes and then have the responsibility to develop the course to meet those outcomes as they deem appropriate. Where the cut line falls between fixed and customizable aspects of a course depends on the program and discipline.

- Separating Assessment and Instruction: A curriculum can be structured to allow for faculty to develop courses as they deem appropriate to meet set goals, but these set goals are assessed by a separate faculty member or group of faculty. In some models, this might be a specific set of assignments or problems placed strategically across a curriculum, a standardized test, or a rubric-evaluated paper that focuses on specific learning goals. The responsibility of assessing student learning, or grading student work, might be separated from instruction and content facilitation. This model not only provides faculty with a great deal of autonomy as to how materials are presented and what is presented but also strongly ties their work to specific learning goals.

The importance of this approach resides in the hiring and retention of high-quality faculty, many of whom might never consider working within a relentlessly top-down curricular environment. In addition, as discussed earlier in this section, the act itself of making a curricular structure explicit to those who develop and maintain it has many benefits.

Stepping back, there are several salient issues that provide the foundation for thinking about coordinated curricular structures. These include the following:

- The Size of the Instructional Context: How many colleges, schools, programs, courses, sections, faculty, or students are involved?

- Instructional Responsibilities: Who is responsible for organizing and monitoring the instructional contexts? Who is responsible for teaching students?

- Level of Coordination: Does the instructional context involved share program outcomes, course outcomes, lesson and weekly objectives, activities, projects, assignments, or texts?

- Degree of Coordination: How structured is the coordination at the various curricular levels where it occurs?

- Instructional Control: Is the instructional context mandated by the institution (federal or state government, accrediting agency, academic division, school, program, department, etc.); is it encouraged by the institution; is it a voluntary faculty-organized endeavor; or is it some combination of each?

- Locus of Assessment: How is quality assurance (e.g., learning assessment, teaching quality, student satisfaction) implemented within the curriculum?

There is no single appropriate curricular model that will work across instructional experiences, programs, disciplines, or institutions. By better understanding the range of available curricular models and by articulating the means of curricular production explicitly and intentionally, educators have a much stronger set of tools at their disposal to support student learning.

Decision-Support Methodologies

In many industries, predictive modeling (e.g., logistic regression, neural networks, decision trees, support vector machines) and segmentation modeling (e.g., clustering analysis, categorization analyses) have been used extensively to provide better customer insights and inform executive decisions. For example, in order to more efficiently predict specific customer responses to direct mailing campaigns, the insurance industry has deployed sophisticated modeling techniques. The main goal of developing these statistical models is to attach probabilities to the behaviors of segments of the population and identify which groups will behave significantly differently with respect to a desired action (i.e., maintaining a subscription or responding to an advertisement), based on key demographic, financial, psychographic, or behavioral variables.

In for-profit higher education institutions, these same tools are being deployed to provide leadership with insights about student behaviors (e.g., likelihood to retain), performance (e.g., probability to achieve specific outcomes), and satisfaction. Given the demographics and career history of most of the leadership in the for-profit sector, this is not surprising; most executives running these institutions come over from industry and bring with them rich analytic experiences.

Traditional sector higher education has been slow to adopt analytically informed decision-support processes. Initial use in academe is focused on areas most closely aligned to their business counterparts (e.g., marketing, enrollment, advancement). However, the application of statistical modeling is being used to support a greater number of core academic functions.12 Currently, most of this effort is focused on better understanding student retention and enrollment yields.

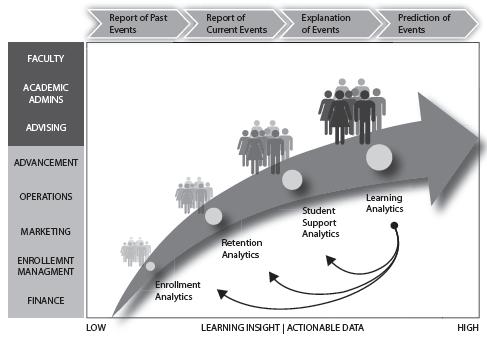

Figure 9.1. Maturing academic and learning analytics.

Figure 9.1 displays a model of the growth of analytics along several continua: low-to-high insight, business-to-academic application, historical reporting to predicting future behaviors, and enrollment-to-learning analytics (common application path). The ultimate and, arguably, the most difficult application of these techniques involves their use to better understand student learning and to more efficiently and meaningfully inform instruction, curricula, and learning support. This area, known as learning analytics, is one of the least developed and most promising areas of analytic work in higher education.

The use of learning analytics can inform a range of questions about student learning. The following examples help illustrate the point:

- Predicting Outcome Achievement: A score can be attached to a student that reflects the probability he or she will achieve an identified learning outcome at a given level. These models make use of data sets containing test scores, achievement in previous courses, survey data, learning styles information, demographic data, and learning management system (LMS) activity data. The resulting insights can be used to target interventions and develop well-structured curricula.

- Course Dashboarding: Modeling insights can be used to provide instructors with the most salient student data correlated to success in a specific course. These data can be displayed in a dashboard to provide at-a-glance actionable information to instructors who can then use the information to tailor their instruction based on learning data.

- Curricular Evaluation: Modeling techniques can be used to identify correlations among learning outcomes in order to define data-evidenced course prerequisites and course sequencing. For example, a complexity index can be developed for course outcomes across a program. The index might indicate the difficulty of achieving each outcome and how achievement (or lack of achievement) of a set of outcomes predicts future achievements.

- Setting Course and Instructional Policies: Modeling can identify which data from the LMS are the strongest correlates to student performance. Once these LMS-evidenced behaviors are identified, they can be used to set policies and expectations.

While for-profit institutions have made use of these techniques, their use often runs into trouble when they are applied inappropriately, for example, when lack of sufficient academic experience or an unfamiliarity with teaching and learning leads to ineffective (or, in the worst cases, unethical) use of educational data. For example, one might build a predictive model based on zip+4 census data that does a very good job of segmenting the population into those highly likely to retain to graduation and others who have a very low probability of success. In a business context, the model could provide insights on customer behaviors and inform marketing decisions. In an educational context, the fact that the segmentation may actually reduce to financial status may make its use inappropriate for admissions or admission testing decisions (e.g., if the institution has a mission to improve access).

Best Strategic Management Practices for the 21st Century

For-profit postsecondary institutions’ leadership is normally organized by administrators with limited academic experience, whereas nonprofit institutions are normally managed by academicians who are not savvy strategic experts. The former are effective in leading their institutions to meet the changing environmental challenges; however, due to their limited academic insights, they are at a disadvantage in creating strong academic programs. The latter, while experts in creating strong academic programs, do not possess the strategic management expertise in responding to changes quickly or effectively.

As we have demonstrated, these broad differences play out in structural advantages and challenges for each institution type. The prospect of synthesizing the advantages of the structures, in ways that also minimize their inherent weaknesses, provides a model of how institutions of higher learning can better meet the needs of changing student populations. The specific recommendations we endorse in this chapter can therefore be viewed as contributions to a conceptual road map of hybrid institutional structures better able to meet the changing needs of higher education in the 21st century. The key elements of these hybrid institutional structures include the following:

- Applying management techniques developed at the best for-profit institutions of higher learning for integrating adjunct faculty into their institutions

- Applying to all faculty, including faculty outside the tenure track, shared governance processes developed at the best not-for-profit institutions

- Increasing institutional effectiveness by applying the best data and analytics decision-making processes developed at both for-profit and not-for-profit institutions

- Increasing the level of coordination within curricular structures as needed to better measure and ensure student achievement and making explicit and intentional the means of curricular production and the way members of a community work together to transmit and grow curricula

- Strategically managing institutions of higher learning to promote these goals:

- Alignment of educational mission and financial success and mission-driven and profit-driven institutional values

- Alignment of institutional incentive and accountability systems, eliminating disconnects that damage institutions’ credibility

- Elimination of academic structures that maintain silos and block collaborations

Over the coming decades, no single model of higher education will win out over the others—each offers unique ways to support broad ranges of students from diverse populations. However, the authors believe that weaving multiple paths through the structural challenges and advantages of each type of institution will better our chances of meeting our students’ learning needs in ways that will help our nation to advance.