The 21st Century Higher Education Strategy Road Map

Hamid H. Kazeroony

We examined changes dominating the higher education landscape in the first decade of the 21st century. We reviewed the organizational cultural dimensions that can contribute to the positive development of institutions of higher education (HEIs). We explored how learners and their approach to knowledge acquisition have changed and how new technologies can address their needs. We reviewed administrative and academic structure in current institutions, sources of possible funding for students and institutional operation, and changes in existing institutions, and provided an overview of regulatory agencies. Finally, we addressed marketing institutions and their programs. The question is, where do we go from here?

Now we will examine the structural possibilities that one should review in implementing new strategies for specific institutions, depending on the need of their particular stakeholders.

Which Model to Follow?

Each modality presents unique advantages and disadvantages. Online modality is asynchronous, provides convenience, and offers an easy way to expand programs without expenses associated with building, maintenance, and operation of facilities. However, online programs are not a panacea. Many institutions, particularly public and or nonprofit private institutions, may rely on endowments and spend millions without appropriate infrastructure to service learners remotely, and hence their operation may run into trouble or foil quickly.1 Therefore, before marching to the online drum, one should consider all the institutional realities and the necessary support system to make the program viable. However, we should find ways to make online education a reality since it is growing much faster than traditional education. Based on a 2008 report, “Staying the Course: Online Education in the United States,” published by Sloan-C consortium, online enrollment growth was 12.1% versus 1.2% of growth for overall higher education.2 This finding provides support for shifting institutional resources and aligning support services to the growth segment—online.

Hybrid modality presents a convenient way to familiarize less tech savvy learners with online learning. Students begin their courses with face-to-face meetings with instructors and administration and continue their learning online; they then return to finalize their courses in person. Finally, face-to-face offers the convenience of meeting in person and provides direct interaction with faculty and administrators for learners. However, each modality possesses its disadvantages. A study reviewing the differences between online and campus graduate courses found a higher rate of dropout in online graduate programs than the campus-based courses.3 In hybrid modality, if a learner misses the face-to-face meeting, he or she loses the entire benefit of the modality. Additionally, the hybrid modality requires investment in fiscal locations and technology-increasing expenses. Face-to-face modality requires investment in facilities, restricts growth due to the need for classrooms, and is inconvenient to many adult learners who must add the travel time and regimented class time to their already busy schedules.

Technology Application

A survey conducted by the U.S. Department of Education (USDE) in 2006–2007 found that two-thirds of all the Title IV eligible two- and four-year institutions use some form of technology to offer either a hybrid or distance education in a synchronous or asynchronous environment, accounting for 12.2 million registrants.4 There are various associations and publications that address the integration, use, and assessment of technology use in higher education.5

The USDE website provides a plethora of guidance on technology use, integration, and assessments.6 Platforms that make online teaching possible are few, some are more powerful than others, and each has a different capability and copyright issues. Examples of such platforms are e-College, Blackboard, Angel, Moodle, Wimpa, and Jenzabar. Technologies targeted at administrative functions, such as accounting, financial aid processing, student contact, and scheduling courses, are readily available, and many companies are willing to grant annual licensing and copyrights for educational operation in exchange for per-person use fees. Examples of the administrative platforms are ORACLE account management, various PeopleSoft financial aid and contact management, Jenzabar contact management and enrollment system, and Regent financial aid management, to name a few in administrative technologies. Therefore, there are adequate technologies for reducing the number of employees, improving customer service, and enhancing learning experience. Hence, technology utilization and application is becoming easier due to availability as discussed and utilization by the end users.

Expansion of technology infrastructure and enhancement of computing have led to new requirements. The Economist Intelligence Unit, based on an international survey, concluded that technology continues to be an integral part of higher education—administratively and academically.7 Various cloud technologies, such as enhancing computing, storage, and software revision capabilities, are empowering higher learning institutions to position themselves to address the service and learning needs of the 21st century students. As these new developments demonstrate, there is a need for better integration of technology and the refinement of the job description for those who are connecting the dots in these institutions. The growth of technology requirements and the use of various software and hardware in higher education require the chief information officers to operate strategically at the highest institutional level while managing the tactical issues in integrating the technology for smooth operational educational experience.8

What Do We Need for Accreditation?

As a starting point, an institution must determine how to become accredited. Appropriate accreditation determines the programs an institution offers, the annual cost of membership, and the level and amount of available funding. In addition, the form of accreditation communicates particular expectations to students who enroll in its programs and communicates to employers and external stakeholders what to expect from the learning outcome of their graduates. Depending on the nature of degrees offered, an institution should align itself with the appropriate accrediting body to provide credibility to its students and enable its students to transfer their degrees or their work to other institutions as required. However, before one can decide how to approach accreditation, it is important to understand the nature of the process and structure of accrediting bodies and their relationship with the U.S. government.

The USDE does not accredit any institution. The U.S. secretary of education recognizes private entities that conduct peer review in accrediting individual institutions as the authority for all practical purposes, in addition to individual state governments that may exert varying degrees of control over the process.9 The USDE articulates the purpose, the process, and type as the following.

Some Functions of Accreditation

The USDE explains that accreditation means the following:

- Verifying that an institution or program meets established standards

- Assisting prospective students in identifying acceptable institutions

- Assisting institutions in determining the acceptability of transfer credits

- Helping to identify institutions and programs for the investment of public and private funds

- Protecting an institution against harmful internal and external pressure

- Creating goals for self-improvement of weaker programs and stimulating a general raising of standards among educational institutions

- Involving the faculty and staff comprehensively in institutional evaluation and planning

- Establishing criteria for professional certification and licensure and for upgrading courses offering such preparation

- Providing one of several considerations used as a basis for determining eligibility for federal assistance

The Accrediting Procedure

- Standards: The accrediting agency, in collaboration with educational institutions, establishes standards.

- Self-study: The institution or program seeking accreditation prepares an in-depth self-evaluation study that measures its performance against the standards established by the accrediting agency.

- On-site evaluation: A team selected by the accrediting agency visits the institution or program to determine firsthand if the applicant meets the established standards.

- Publication: Upon being satisfied that the applicant meets its standards, the accrediting agency grants accreditation or preaccreditation status and lists the institution or program in an official publication with other similarly accredited or preaccredited institutions or programs.

- Monitoring: The accrediting agency monitors each accredited institution or program throughout the period of accreditation granted to verify that it continues to meet the agency’s standards.

- Reevaluation: The accrediting agency periodically reevaluates each institution or program that it lists to ascertain whether continuation of its accredited or preaccredited status is warranted.

Types of Accreditation

There are two basic types of educational accreditation: one identified as “institutional” and one referred to as “specialized” or “programmatic.”

Institutional accreditation normally applies to an entire institution, indicating that each of an institution’s parts is contributing to the achievement of the institution’s objectives, although not necessarily all at the same level of quality. The various commissions of the regional accrediting associations, for example, perform institutional accreditation, as do many national accrediting agencies.

Specialized or programmatic accreditation normally applies to programs, departments, or schools that are parts of an institution. The accredited unit may be as large as a college or school within a university or as small as a curriculum within a discipline. Most of the specialized or programmatic accrediting agencies review units within an institution of higher education that is accredited by one of the regional accrediting commissions. However, certain accrediting agencies also accredit professional schools and other specialized or vocational institutions of higher education that are free standing in their operations. Thus a specialized or programmatic accrediting agency may also function in the capacity of an institutional accrediting agency. In addition, a number of specialized accrediting agencies accredit educational programs within noneducational settings, such as hospitals.10

There are two types of accrediting agencies: (1) registered and recognized directly by the USDE and (2) registered and recognized by the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA), which includes member organizations whose operational scope can be divided into regional, national faith-related, national career-related, and programmatic, as well as various higher education associations.

CHEA is a private entity that strives for self-regulation of its member organizations to ensure quality of education in the United States.11 CHEA accreditation (through its member organizations) provides program and degree credibility, facilitates public and private funding to institutions, ensures international mobility of the earned degrees, assists in new innovations while maintaining quality, protects students and consumers against abuse and fraud, and provides acceptance of programs to states requiring licensures for operation.

As stated earlier, accreditation is the cornerstone of degree recognition domestically and internationally, funding through Title IV, and various other funding through federal and state governmental programs. Under Title IV Higher Education Act of 1965, when the USDE changes regulations that may impact any part of the program, it must provide an opportunity for all stakeholders to provide input unless there are compelling rationales by the USDE secretary to forgo the established rulemaking.

Rulemaking is the process where the USDE opens its decision making to all interested parties in higher education through their legal representatives, who are usually individuals representing associations of various degree-offering institutions, lenders, and other stakeholders in the process.12 Therefore, each institution has the opportunity to work through its association’s or its accrediting body’s representatives to communicate its interest regarding the USDE new rules that may impact them adversely or to protect those rules that benefit them. However, the issues arise when accrediting bodies may have established ambiguity in defining criteria.

In a recent exchange between the USDE Office of Inspector General (OIG) and Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS), the OIG asked SACS for clarification on (1) what guidance SACS provides to institutions regarding program length and credit hours, (2) what guidance SACS provides to peer reviewers to assess program length and credit hours when evaluating institutions, and (3) what documentation SACS maintains to demonstrate how it evaluates institutions’ program length and credit hours.13 At the heart of this inquiry is the definition of credit hours, which may vary in different institutions, programs, and modalities. The OIG also addressed the same concerns in December 2009 with the Middle States Education Commission on Higher Education.14 However, the OIG wrote its most aggressive letter to the USDE undersecretary for higher education to take actions against the Higher Learning Commission of the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools, requesting its removal from the list of accrediting bodies. Therefore, going forward, it is highly advisable for each institution to clarify its standards to surpass the accrediting bodies’ rules to protect its accreditation and, in turn, its governmental funding. The issue is more important in hybrid and online programs where the interaction is asynchronous.

What Structure Should We Have?

Higher education institutions, based on USDE recognition, can be organized as follows:

Higher education institutions in the United States are organized and licensed or chartered as nonprofit or for-profit corporations, regardless of whether they are public or private. These corporate entities are governed by boards of trustees, who are citizens appointed by a governor or legislature (public institutions) or elected by the board itself (private institutions). Institutions thus established may be single-campus institutions, multicampus institutions, or systems comprising several independent institutions.

Public institutions, in addition to having governing boards appointed by state authorities, will also receive some annual allocation of state budget funds; some of their property may be state owned; and they may be subject to state regulations of other kinds depending on the nature of their relationship to the state as defined in their charters. Public institutions are internally self-governing and autonomous with respect to academic decision making.

Private institutions are independent of state control even though they are licensed or authorized by state governments. They may be nonprofit or for-profit and may be secular or affiliated with a religious community. Some private institutions may be authorized by state governments to receive state operating funds and to provide some public services, such as operating publicly funded academic programs or functioning as state land-grant institutions receiving federal funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Both public and private institutions may charge students tuition and fees, may receive gifts and donations and hold an invested endowment, and may earn income from research and instructional grants and contracts. Public institutions may have restrictions set by states on how much they can charge students and may be required to keep nonstate gifts and other income separate, often in foundations administered by alumni.15

Addressing Silos

Public and private nonprofit institutions are usually organized into compartments, such as admission, colleges or schools, financial aid office, registrar office, administration, and student services. In these settings, each compartment has its own rules and acts quasi-independently of other parts. Each part, in many respects, interacts with students independently of how other departments treat the student.

The Learner

To illustrate how silos affect the learning and service experiences, we will advance the following scenario.

Scenario 1: The Faculty

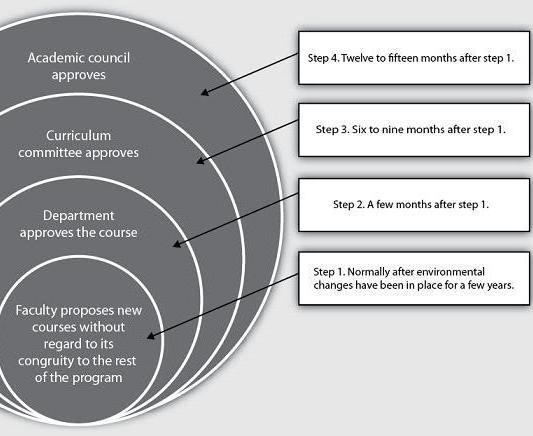

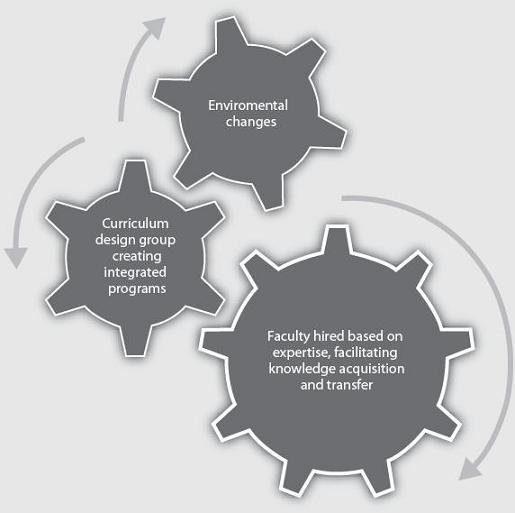

In private nonprofit and public universities, each faculty member is recruited to serve a particular department as a subject expert. According to a survey, the highest average pay for faculty in more demanding fields is approximately $129,000 per year,16 which is usually equal or less than the administrators’ or athletic departments’ personnel average pay.17 Therefore, faculty members face numerous challenges in their silo. First, their pay does not correspond to their level of expertise or the money spent on their education to provide an appropriate level of services to learners. Second, each faculty member works within his or her department isolated from other departments, creating disintegrated learning processes. The problem becomes more acute when environmental changes require changing curriculums, which may necessitate combining departments to accommodate new competencies. Faculty members become defenders of their silo, and students are not served for their learning needs to correspond to new competencies required by businesses or other organizational entities such as government. Third, curriculum redesign by faculty members from inception to implementation can take an average of two years, which makes response to environmental changes very slow. Fourth, faculty members are subject experts, but they are not experts in communicating and synthesizing the information that can easily be transformed into a knowledge base for new competencies or efficiently transmitted to intended learners.

Scenario 2: Funding

Postsecondary institutions may be funded by various federal government financial aid loans, grants, states’ grants, GI bill provisions, Veterans Administration funding, private loans, scholarships solicited by various means, endowments created by various donations, and employers’ reimbursement programs, among many other methods. Funding is subject to programmatic and institutional eligibility, as well as an institution’s fundamental belief in taking advantage of any or all funding sources.

An institution that receives funding from the government for the purpose of students’ education under Title IV provisions must satisfy programmatic and institutional accreditation as outlined by the USDE. An institution must be accredited by appropriate regional or professional accrediting bodies and satisfy appropriate state department of education rules to take advantage of any federal and state funding—grants and loans. Therefore, when operating online or distance programs, institutions must review each specific state’s rules and abide by their rules to ensure they are in compliance with multijurisdictional accreditations. For examples, some states may require an institution to have a physical campus in their state and approved by that state for offering online and distance education before being allowed to recruit students from that state. If such rules are not followed, an institution will risk losing its accreditation and hence its funding by the federal government.

There are two common scenarios that can take place based on the institution that a student is attending. Normally, in traditional schools where there are semester or quarter systems, students will receive their funding for two semesters or three quarters. In these cases, the disbursements are received in two or three installments based on the number of credit units taken—where at least part-time attendance must be established to receive the prorated part of the financial aid. In a nontraditional setting with federal government funding, where courses are designed for students to attend one course at a time, each course lasting five or six weeks, installments for full-time students are received for 12 credit hours at a time, and students can start their education at any time during the year. However, grants are based on students’ and parents’ financial needs and are on a different cycle than loans. The year for any grant starts on July 1 and ends on June 30 of the following year. Therefore, administrators must monitor student eligibility as grant eligibilities, such as the Pell Grant, are based on the results of tax filing from each prior year.

For example, let us assume that a student started his or her education in either a traditional or nontraditional education in January 2011. In this case, the student’s eligibility for loans and grants will be determined by the tax filing that student or his or her parents did in 2010 for 2009. Now let us also assume that this student will continue to be eligible for loans based on the cost of attendance, but the grant eligibility may change. In this particular example, the student will receive grants and loans for the first part, 12 credit units regardless of the modality (due to the time of start), but to receive the second installment, the student must provide new tax information for 2010 that must be filed by April 15, 2011.

What Changes Are Needed?

There are a number of factors leading to required changes in higher education. Recent signs of changes in elementary and high school education in 70% of school districts that are adopting distance modality as an acceptable approach to teaching18 require higher education establishments to reexamine their administrative and academic processes to respond to the needs of a new generation of incoming students. Also some private, for-profit universities, such as the parent company of University of Phoenix, have adopted McDonaldization of higher education—bringing the customers in when they are very young and creating a captive market audience for the rest of their educational life span. In 2008, through its subsidiary (Insight), Apollo Group, Inc. began offering high school programs in association with 10 different states’ school districts.19 Higher education institutions, like any other organization, have become subject to customer satisfaction in the delivery of learning services and new learning modalities to accommodate new learners.20 Higher education institutions must change globally in light of changes to fees and a need for student-services support.

Marketing Your Institution and Its Programs

A National Public Radio report suggests that higher education marketing has become more sophisticated and costly in attracting students to their institutions.21 Indeed, some companies, such as the Institute for Professional Development, a subsidiary of Apollo Group, Inc., charge a percentage of tuition in return for marketing and enrollment activities of smaller private colleges. Both public and private universities rely on marketing firms to help them navigate through marketing, branding, and strategic positioning, as evidenced by activities of some marketing firms, such as Stamats.22 However, marketing can be a complex issue for higher education institutions.

Too often various segments of the same institution may be on a collision course when marketing their programs. For example, one division’s marketing may be in conflict with the mission of its institution or how other divisions market their programs.23 Also, organizations such as Sloan Consortium provide support for university officials who would like to learn more about marketing their programs in an online environment.24 As one study suggested, the web provides a powerful contextual and visual tool for attracting learners to a higher learning institution, but a majority of institutions have not realized the potential of this source.25 Therefore, admission offices must use the web to identify learners’ demographics, their learning habits, and so on to reach appropriate learners for their particular offering at their institutions.

Creating the Products: Programs and Courses

Programs must be responsive to the societal needs for new work skills requirements. As a norm, for-profit universities do a better job of addressing the issue than the nonprofit and public institutions.26 Programs must address competencies and skills required by the marketplace. For example, Bank of America asked for an Algorithmic Trading Support Engineer with the following requirements:

Required Skills

- Strong understanding of Solaris, Linux, and Windows operating systems

- Experience working on a trading floor that supports Electronic Trading Systems. Ability to function in a high pressure environment.

- Trace transactions through the system and conduct research beyond basic scripts and monitoring; research tools provided

- Basic knowledge of FIX for examining logs and troubleshooting problems

- Knowledge of Equity Algorithmic Trading

- Excellent communication skills, methodical, and a fine attention to detail

- Unix shell/perl/python scripting skills

- Good knowledge of database technologies (Microsoft SQL, mysql, Sybase and Oracle).27

We provided a comprehensive and critical view of the higher education system, its idiosyncrasies, some practices from European counterparts and institutions, and ways to reorganize the current institutions to be more successful in serving our learners as customers of such institutions and consumers of knowledge. However, each institution must explore its unique opportunities.