Sociocultural and environmental impacts of tourism

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

list the potential social and cultural benefits of tourism

describe how tourism can promote both traditional culture and the modernisation process

explain commodification and its positive and negative consequences, and understand how tourism can contribute to this process

differentiate between destination frontstage and backstage and discuss their implications for the management of tourism

explain the linkages that can exist between tourism and crime

identify the circumstances that increase or decrease the probability that a destination will experience negative sociocultural impacts from tourism

assess the nature of resident attitudes towards tourism

describe the potential positive and negative environmental consequences of tourism for destinations

cite examples of the environmental impact sequence using an array of stressor activities

discuss the utility of ecological footprinting as a means of measuring environmental impact.

254

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

The basic aim of tourism management at a destination-wide scale is to maximise the sector’s economic, sociocultural and environmental benefits, while minimising the associated costs. To meet this objective, destination managers must understand the potential positive and negative impacts of tourism, and the circumstances under which these are most likely to occur. Chapter 8 considered economic costs and benefits, and concluded that small-scale, developing destinations — that is, the ones which arguably need tourism the most — are most likely to incur high costs as a consequence of tourism development. Chapter 9 extends our understanding of tourism impacts by considering their sociocultural and environmental dimensions. The following section examines the alleged sociocultural benefits of tourism, while the ‘Sociocultural costs’ section considers its potential sociocultural costs as expressed through the phenomenon of commodification, the demonstration effect and the relationship between tourism and crime. The possible environmental benefits of tourism are then discussed, and this is followed by an examination of its potential environmental costs, as modelled through the environmental impact sequence. The consideration of the sociocultural dimension before the environmental dimension is not intended to suggest the greater importance of the former, but rather that the cautionary platform (see chapter 1) initially placed more emphasis on social and cultural issues in its critique of the tourism sector. The two dimensions, in reality, are often closely interrelated, and both are intimately related to the economic dimension.

SOCIOCULTURAL BENEFITS

SOCIOCULTURAL BENEFITS

Although supporters of the advocacy platform emphasise the economic benefits that could result from tourism for a destination, they also cite various affiliated sociocultural advantages. These include:

the promotion of cross-cultural understanding

the incentive value of tourism in preserving local culture and heritage

the promotion of social stability through positive economic outcomes.

Counter-arguments are made for all of these impacts in the sections that follow, but the intention in this section is to present only the advocacy point of view.

Promotion of cross-cultural understanding

When individuals have had limited or no contact with a particular culture, they commonly hold stereotypical, or broad and usually distorted behavioural generalisations, about that culture and its members. In the absence of direct experience, stereotypes provide a set of guidelines that are used to indicate what can be expected when encountering members of that culture. It can be argued that direct contacts between tourists and residents dispel such stereotypes and allow the members of each group to perceive one another as individuals and, potentially, as friends (Tomljenovic 2010). Tourism is thus seen as a potent force for cross-cultural understanding because huge numbers of people come into contact with members of other cultures both at home and abroad. In Australia, direct contacts with Japanese and other Asian tourists have undoubtedly contributed to the erosion of stereotypes held by some Australians, while the same effect has also occurred in reverse through the exposure of outbound Australians to Asia and other overseas destinations. As such, tourism can be seen as a grassroots mechanism that contributes to improved relations between countries (Weaver 2010a).255

A force for world peace

One manifestation of this cross-cultural perspective is the perception of tourism as a vital force for world peace. Aside from spontaneous day-to-day contacts, this considers the role of tourism in facilitating deliberate ‘track-two diplomacy’, or unofficial face-to-face contacts that augment official or ‘track-one’ avenues of communication. This phenomenon is illustrated by the way that cricket Test matches in 2004 helped to build rapprochement between India and Pakistan, which have fought three wars since 1947 (Beech et al. 2005). Preceded by confidence-building measures such as an agreement to resume normal diplomatic and civil aviation links, a decision was made in 2003 to hold a Test series between the countries in Pakistan the following year. The government of Pakistan issued visas for 10 000 Indians, whose warm and hospitable treatment by their Pakistani counterparts during the match was widely reported in the Indian press. More importantly, a regional television audience of 600 million was treated to a remarkable spectacle of incident-free sporting conduct and camaraderie throughout this ‘proxy war’, which ended in an Indian victory. Beech et al. (2005) speculate that this massive grassroots exposure to a sustained atmosphere of mutual goodwill has done and will do much to build the impetus for further improvement in the India–Pakistan bilateral relationship, a consideration that is of no small import given the nuclear-weapon capabilities of both countries.

Yet, such initiatives are inherently fragile. In 2008, cricket teams from Australia, England and New Zealand pulled out of Pakistan tours due to security concerns, while the country’s sporting reputation was devastated in March 2009 by terrorist attacks against the visiting Sri Lankan cricket team. Within the tourism sector itself, initiatives that explicitly attempt to foster peace and cross-cultural understanding include Oxfam’s Community Aid Abroad tours to Guatemala, and the reality tours offered by the human rights organisation Global Exchange (Higgins-Desbiolles 2010).

Incentive to preserve culture and heritage

Tourism has the potential to stimulate the preservation or restoration of historical buildings and sites. This can occur directly, through the collection of entrance fees, souvenir sales and donations that are allocated for this purpose, or indirectly, through the allocation of general tourism or other revenues to preservation or restoration efforts intended to attract or sustain visitation. This is best illustrated at a destination-wide scale by tourist–historic cities such as Prague (Czech Republic), Bruges (Belgium), Kyoto (Japan) and York (United Kingdom) where the restoration and revitalisation of entire inner-city districts has been induced and sustained at least in part by considerations of tourism potential (Munsters 2010). Australia does not have any urban places that would qualify as tourist–historic cities but has examples of tourism-related historical preservation ranging from relatively large sites such as the Port Arthur convict ruins in Tasmania and the Millers Point district of Sydney, to small sites such as the Springvale Homestead in Katherine, Northern Territory. Destination residents benefit from these actions to the extent that restored sites are more attractive to tourists and therefore generate additional revenues, and because they provide residents with opportunities to appreciate and experience their own history that might not otherwise exist.

The same principles apply to culture. Ceremonies and traditions that might otherwise die out due to modernisation are sometimes preserved or revitalised because of tourist demand. As with historical sites, the examples are numerous, and include the revival of the gol ceremony in Vanuatu, where boys and young men jump from tall wooden towers in a way that superficially resembles bungee jumping, and the revival of 256traditional textile and glass crafts in Malta. Other examples are the expansion of Native American arts and crafts in the American Southwest and the revitalisation of traditional dances and ceremonies on Bali (Barker, Putra & Wiranatha 2006). In the case of the American Southwest, Native American artists acknowledge their creation of new themes to appeal to tourists, but maintain traditional manufacturing processes. Accordingly, they regard such art as an expansion rather than alteration of their authentic material culture (Maruyama, Yen & Stronza 2008). Similar dynamics pertain in northern Australia’s Arnhem Land, where demand from tourists has contributed to the stimulation of traditional woodcarving but also the appearance of new designs (Koenig, Altman & Griffiths 2011).

Promoting social wellbeing and stability

Through the generation of employment and revenue, it is commonly assumed that tourism promotes a level of economic development that is more conducive to the ultimate goal of increased social wellbeing (see Breakthrough tourism: Gross national product or gross national happiness?). This promotion also occurs when a destination attempts to improve its international competitiveness by offering services and health standards at a level acceptable to visitors from more advanced economies. Although implemented because of tourism, local residents derive an obvious and tangible social benefit from, for example, the elimination of a local malaria hazard or the introduction of electricity, anticrime measures or paved roads to the district where an international-class hotel is located.

breakthrough tourism

![]() GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT OR GROSS NATIONAL HAPPINESS?

GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT OR GROSS NATIONAL HAPPINESS?

Among tourism researchers, Bhutan has been long recognised for strict visitor quotas and for focusing its economic development efforts around the seemingly facetious concept of gross national happiness (GNH). However, in 2011, the United Nations endorsed the concept and established a panel to consider how its four principles of equitable social development, cultural preservation, environmental conservation and good governance could be integrated into the more conventional development strategies of other emerging economies (Kelly 2012). The significance of GNH is given some validity due to the fact that many of the wealthiest societies in terms of traditional gross national product (or GNP; the value of all goods and services produced in a given country during a given year) also suffer high rates of depression, crime, chronic medical problems and degraded natural environments. As such, they cannot therefore be considered ‘developed’ in ways that ultimately matter the most to people, despite the common assumption that happiness is a consequence of the materialism which results from high economic output. Indeed, the Bhutanese remain poor from a GNP perspective, but they are apparently rich in GNH. The maintenance of strict visitor quotas (just 4000 Western visitors were allowed in 1996) as part of a ‘low-volume high-yield’ strategy was a reflection of its GNH principles, so it is noteworthy that the government of Bhutan has now 257embarked on a plan to dramatically increase the number of inbound tourist arrivals from Western countries. In 2011, 64 038 Western tourists visited the country, representing a 57 per cent increase over 2010. Notably, these visitors continue to be described as ‘high-end’ (Tourism Council of Bhutan 2012). It remains to be seen whether this apparent trajectory of high-end, high-volume inbound tourism can be maintained, and whether such growth-oriented tourism can reinforce the aspirations for high gross national happiness.

SOCIOCULTURAL COSTS

SOCIOCULTURAL COSTS

Supporters of the cautionary platform have acknowledged that tourism can produce positive sociocultural outcomes under certain conditions, but maintain that unregulated mass tourism development is more likely to result in substantial social and cultural costs to destination residents as well as tourists. This is especially true, it is argued, if those destinations are located in less developed countries or peripheral areas within emerging economies. The prospect of widespread dissatisfaction among local residents as a result of inappropriate tourism development is an extremely important consideration for destination managers, since this can lead to direct and indirect actions against tourists and tourism that can destabilise a destination and give rise to an enduring negative market image. The maintenance of support among local residents through the prevention and amelioration of negative impacts is, therefore, a prerequisite for the long-term wellbeing of the tourism sector managed from a resilient systems perspective. The following subsections examine the main sociocultural issues that influence the management of tourism destinations.

Commodification

The commodification of a destination’s culture, or its conversion into a commodity in response to the perceived or actual demands of the tourist market, is commonly perceived as a major negative sociocultural impact associated with tourism (Matheson 2008). To the extent that this confers a tangible monetary value on a product (i.e. the culture) that already exists but otherwise generates no economic return, it may be regarded as a positive impact. The problem, however, occurs when the inherent qualities and meanings of cultural artefacts and performances become less important than the goal of earning revenue from their reproduction and sale. Concurrently, the culture may be modified in accordance with the demands of the tourist market, and its original significance eroded or lost altogether. While this was not seen as problematic among the aforementioned Native American artists in the American Southwest, there are several ways that less positive cultural commodification can occur as a result of tourism, and the following scenario gives one extreme possibility.

Phase 1. Tourists are rarely seen in the community, and when they do appear, are invited as ‘honoured guests’ to observe or participate in authentic local ceremonies without charge. They may be given genuine artefacts as a sign of the high esteem in which they are held by the local community.

Phase 2. Visiting tourists become more frequent and hence less of a novelty. They are allowed to observe local ceremonies for a small fee, and genuine artefacts may be sold to them at a small charge.

Phase 3. The community is regularly visited by a large number of tourists. Ceremonies are altered to provide more appeal to tourists, and performances are made 258at regular intervals suitable to the tourist market. Authenticity thus gives way to attractions of a more contrived nature. Prices are set at the highest possible levels allowed by the market. Large amounts of cheaply produced — and often imported —souvenirs are made available for sale.

Phase 4. The integrity of the original culture is entirely lost due to the combined effects of commodification and modernisation. Commodification extends into the most sacred and profound aspects of the culture, despite measures taken to safeguard it.

The residents of a destination may obtain significant financial returns from tourism by the fourth stage, but a widely-held contention is that serious social problems arise in association with the loss of cultural identity and the concomitant disruption of traditional norms and structures that maintained social stability (Swanson & Timothy 2012). In addition, conflicts can erupt in the community over the distribution of revenue, appropriate rates of remuneration for performers and producers (who may have formerly volunteered their services) and other market-related issues with which the society may not be equipped to cope. Compounding the issue is the possibility that the progression will occur over a relatively short time period, reducing the opportunity to devise and implement effective adaptive strategies.

Frontstage and backstage

Local residents are not powerless in the face of commodification pressures, and can adopt various measures to minimise their negative impact. Indicative of cultural and social resilience is the strategy of making frontstage and backstage distinctions within the destination (MacCannell 1976). The frontstage is an area where commodified performances and displays are provided for the bulk of visiting tourists. The backstage, in contrast, is an area set aside for the personal or in-group use of local people and, potentially, selected allocentrics, VFR or business tourists. The backstage accommodates the ‘real life’ of the community and maintains its ‘authentic’ culture. As long as the distinctions are maintained and respected by the tourists and local residents, then the community can in theory achieve the dual objectives of income generation from tourism (mainly in the frontstage) and the preservation of the local way of life as sanctuaries where one can escape the tourists (mainly in the backstage).

The distinction between frontstage and backstage can be implicit or it can involve some kind of physical barrier or signage to differentiate the two spaces. These range from the crude canvas screens erected by Alaskan Inuit to shield their backyards from the gazing eyes of tourists (as described by Smith 1989), to walls, ditches and ‘do not enter’ signs that attempt to contain tourists within the frontstage. It is possible that the very same space can be differentiated as frontstage or backstage depending on the time, so that, for example, a beach is tacitly recognised as tourist space on weekdays during daylight hours, and as local space at other times. (This effect is observable in the Caribbean, where beaches occupied by tourists during the day often become cricket pitches for local youth in the evening.) Such distinctions can also be made on a seasonal basis. In some countries, the frontstage/backstage principle is applied as part of a comprehensive nationwide strategy for regulating contact between local residents and tourists. For example, all of Bhutan was effectively a backstage when the government strictly controlled the number of inbound Western tourists (Gurung & Seeland 2008). The government of the Maldives (an Indian Ocean SISOD) continues to confine 3S tourism development to selected uninhabited atolls as a means of curtailing 259the influence of Western tourists on the country’s conservative Muslim population (Shakeela & Weaver 2012).

The frontstage/backstage distinction, however, can have unexpected consequences and dimensions that raise difficult questions about cultural authenticity. In many indigenous communities, it is the frontstage that is occupied by traditional cultural artefacts and performances that have long been abandoned or modified by the community as items of everyday use, but are of great interest to tourists. The backstage, in contrast, is occupied by a cultural landscape that is similar in many respects to that found in nonindigenous communities of a similar size and location, reflecting the evolving and adaptive nature of the living indigenous culture. In such situations, determining the ‘authentic’ setting becomes more problematic.

Prostitution

Prostitution, arguably the extreme form of commodification, can of course thrive in non-tourism settings, but is encouraged by tourism characteristics such as host–guest (i.e. vendor–buyer) proximity, the suspension of normal behaviour by some holidaying tourists, and often large gaps in wealth between tourists and locals. Destination marketing that emphasises cultural and sexual stereotypes is a further facilitating factor. Examples include the use of the suggestive coco de mer fruit by tourism authorities in Seychelles, and an early promotional campaign in the Bahamas that used the phrase ‘It’s better in the Bahamas’. A sexually charged beach culture is also embedded in the promotion of Brazil to foreign tourists (Bandyopadhyay & Nascimento 2010). While successful in attracting some types of tourists, it is less clear whether this form of advertising actually leads tourists to expect sexual promiscuity among local women, or whether such demands, if they exist, are met through increased levels of prostitution. However, there is no doubt that prostitution is well established either formally or informally in many destinations as a result of tourist demand. The male prostitute, or ‘beach boy’, is a familiar figure on the beaches of the Caribbean and in parts of Africa, where competition for female tourists is associated with increased social and economic status for impoverished local males (Berdychevsky, Poria & Uriely 2013).

FIGURE 9.1 Sex workers and tourists in the red-light district of Amsterdam

The sex industry is a very large and well-established formal component of tourism in European cities such as Amsterdam (see figure 9.1) and Hamburg, in South-East Asian destinations such as Thailand and the Philippines, and within some areas of Australia and New Zealand, such as the Kings Cross district of Sydney. Yet sex tourism is a complex phenomenon that should not automatically be condemned as unequivocally negative. Although coercive and child-focused sex tourism clearly are great evils that cannot be justified, some researchers controversially argue that sex tourism can be relatively benign under circumstances where it empowers and financially benefits sex workers (Bauer & McKercher 2003).260

The demonstration effect revisited

The concept of the demonstration effect as a potential economic cost for destinations was considered in chapter 8. From a sociocultural perspective, problems may occur when residents (usually the young) gravitate towards the luxurious goods paraded by the wealthier tourists or the drugs and liberal sexual mores demonstrated by some tourists. As a result, tensions result between the older and younger community members, as the latter increasingly reject local culture and tradition as inferior, in favour of modern outside influences (Mathieson & Wall 2006).

Case studies as diverse as the Cook Islands (Cowen 1977) and Singapore (Teo 1994) provide evidence for a tourism-related demonstration effect within local societies. However, as with most phenomena associated with tourism, this process is more complex and ambiguous than it first appears (Fisher 2004). Specifically:

The overall role of tourism in conveying and promoting outside influences is usually relatively minor compared with the pervasive impact of television and other media, especially since the latter are also effective vehicles for the promotion of consumer goods. Hence, it is not easy to isolate the specific demonstration effect of tourism.

The effect is not always unidimensional (i.e. tourists influencing locals), but may also involve the adoption of destination culture attributes by the tourists (see chapter 2).

The demonstration effect can have beneficial outcomes depending on the motivations of the adopter and the elements of the tourist culture that are adopted.

Exposure to tourists may cause traditional or ‘anti-Western’ local residents to become even more conservative, indicating the possibility of an ‘anti-demonstration’ effect.

The relationship between tourism and crime

The growth of tourism often occurs in conjunction with increases in certain types of crime, including illegal prostitution (Karagiannis & Madjd-Sadjadi 2012). The tourism-intensive Surfers Paradise neighbourhood of the Gold Coast, for example, reports significantly higher levels of crime than adjacent suburbs. It is tempting to conclude from such evidence that the growth in tourism is attracting increased illegal behaviour. As with most social and cultural impact issues, however, the linkage is more complicated. Like the demonstration effect, the growth of tourism may coincide with a broader process of modernisation and development that could be the primary underlying source of social instability and, hence, increased criminal behaviour. Yet tourism makes a good scapegoat because of its visibility, ubiquity and emphasis on ‘others’ as perpetrators. In addition, some tourism-related crimes are highly publicised, resulting in a disproportionate emphasis on tourism as the reason for such activity. Another perspective is that tourism growth is usually accompanied by growth in the resident population, so that the actual number of criminal acts might be increasing without any actual growth in the per capita crime rate.

The link between tourism and crime, with the aforementioned qualifications, can be discussed first with respect to tourism in general and then with reference to specific types of tourism that entail or foster a criminal connection. A further distinction can also be made between criminal acts directed towards tourists (i.e. mainly a sociocultural impact on the origin region) and those committed by tourists (i.e. mainly a sociocultural impact on the destination region).261

Crime towards tourists

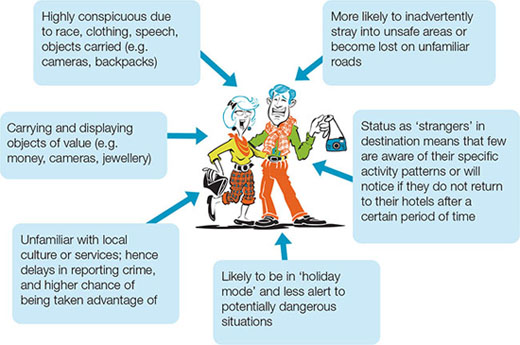

The general connection in the first scenario largely occurs because tourists are often wealthier than local people, and the two groups come into close contact with one another. As a result, tourists offer a tempting and convenient target for the minority of local residents that is determined to acquire some of this wealth for themselves, or who wish to exploit the tourists in some other way. Workers within tourism may be perpetrators, as evidenced by the widespread deviant behaviour that occurs among service workers in many destinations (Harris 2012). At one end of the spectrum where the element of illegality is vague or borderline are residents or workers who engage in deliberate overpricing or begging. Progressing towards the other end of the spectrum are unambiguously criminal activities involving theft, assault and murder, such as those connected with tourism-targeted terrorism. The attractiveness of tourists as targets of crime is increased by several factors, as depicted in figure 9.2.

FIGURE 9.2 Factors that make tourists targets of criminal activity

Crime by tourists

Criminal acts are also committed by the tourists themselves, either against the locals or other tourists. Where certain forms of tourism either encourage or cause criminal activities, tourists are often the initiator or lead players. Sex-related activity that is defined as illegal by destination authorities or under international law, such as that which involves children or human trafficking (Tepelus 2008), is a high profile example. In other cases, the tourism activity is not inherently illegal, but attracts criminal interest. Casino-related gambling is an example of this indirect relationship, given the involvement of organised crime elements, prostitutes and participants who steal or embezzle to feed their gaming addiction (Stitt, Nichols & Giacopassi 2005). Another involves student holiday events, such as the North American ‘spring break’ or Australia’s ‘Schoolies Week’, which are associated with high levels of alcohol and drug consumption (Weaver & Lawton 2013). Rivalry situations involving biker gangs 262or football fans also have a high potential for social unrest, as in the phenomenon of drunken English soccer hooligans (or ‘lager louts’) who travel to France with the explicit intent of fighting with French fans.

Factors contributing to the increased likelihood of sociocultural costs

For the managers of destinations, it is vital to know the circumstances under which negative sociocultural impacts are most likely to occur. This allows them to assess whether these circumstances are present in the destination, and if so, to implement appropriate demand- or supply- side ameliorative measures. If these actual or potential impacts are ignored, there is a danger that the social or cultural carrying capacity of the destination (or the amount of tourism activity that can be accommodated without incurring serious social, cultural and/or environmental damage) will be exceeded. Each of the factors outlined here should not be looked at in isolation, since it is more probable that negative effects will result from a combination of mutually reinforcing circumstances. Thus, the greater the number of factors present, the greater the probability of negative outcomes. No order of priority is intended in this inventory.

Extensive inequality in wealth between tourists and residents

As mentioned earlier, tourists who are visibly wealthier or assumed to be wealthier than the majority of the resident population, as in emerging economies, are more likely to generate resentment and induce a demonstration effect among some residents that cannot be fulfilled by conventional means (e.g. higher wages). Hence, there is a greater probability that these individuals will revert to tourist-directed crime to meet these perceived needs. A broader issue of relevance to this factor of wealth disparity is that residents are just as likely to rely on stereotypes as tourists, prompting many to assume that all tourists from Australia or the United States are extremely wealthy. A widespread sense of envy and resentment can emerge under such circumstances, especially if enclave effects result in minimal direct or indirect benefits to the destination (see the case study at the end of this chapter).

Cultural and behavioural differences between tourists and residents

Large cultural differences can result in the identification of tourists as a group distinct from the ‘local’ population, hence reinforcing the sense of the ‘other’ and, as already discussed, making them more vulnerable to crime and other forms of exploitation. Where the gap between the tourist and resident cultures is wide, the probability of culturally based misunderstandings is also increased, even if tourist actions are well-intended (see Managing tourism: Behold the voluntourist). The problem is exacerbated when tourists make little or no attempt to recognise and respect local sensibilities and persist in adhering to their own cultural norms. The same also applies to the attitudes of local residents, although more of an onus is justifiably placed on visitors since the latter cannot reasonably expect that a destination will transform itself just for their convenience. Inappropriate behaviour has been fairly or unfairly associated with psychocentric tourists (see chapter 6), who allegedly become more prevalent as a destination becomes more developed. For such groups, contact with other cultures is likely to reinforce rather than remove existing cultural stereotypes.263

managing tourism

![]() BEHOLD THE VOLUNTOURIST

BEHOLD THE VOLUNTOURIST

FIGURE 9.3 Voluntourists with Habitat for Humanity

Some critics of conventional mass tourism advocate for volunteer tourism as a more appropriate and effective tool for development in peripheral areas. This form of tourism involves extended visits to places where volunteers (also known as voluntourists) assist with designated aid or research projects, receiving training either beforehand or during the experience. Young adults are disproportionately represented in volunteer tourism. Advocates contend that tangible positive outcomes for destinations are achieved by idealistic tourists who are enlightened by the experience and convey a positive image of themselves and their country of origin to the host community (Barbieri, Santos & Katsube 2012). There are social and environmental manifestations of volunteer tourism. The former is illustrated by United States-based Habitat for Humanity (www.habitat.org), which focuses on building houses for the needy (see figure 9.3). A prominent example of an environmental focus is the Earthwatch Institute (www.earthwatch.org), which coordinates scientific research projects in protected areas and other natural habitats. As participation in volunteer tourism increases, more opportunities are available to assess its actual impacts on host communities. One criticism is the performance of unsatisfactory work due to insufficient training or motivation. Also, it has been suggested that communities continually exposed to volunteer tourism could become dependent and face continued unemployment (McGehee 2012). Undesirable cultural changes may result from locals’ close and prolonged contact with voluntourists, whose motivations may be mostly ego-driven and focused on self-advancement through the demonstration of overseas work experience. Such changes can also manifest themselves in situations where volunteer organisations have religious motivations (Guttentag 2009). One overall result may be the reinforcement rather than breaking down of mutual stereotypes. Critics generally do not advocate the elimination of volunteer tourism, but caution participants to avoid seeing it as a cure-all inherently beneficial to the target destination (Sin, 2010). Better participant screening and provision of training/awareness, as well as better targeting of recipient communities, are ways in which more positive outcomes can be facilitated for both the tourists and communities.

Overly intrusive or exclusive contact

Whether differentials in wealth and culture create social problems is also influenced by the nature of contact between tourists and residents. This is an extremely complex factor, given the large number of individual face-to-face contacts that occur over the course of a typical visit and the numerous variables that mediate such interactions, which include personality type, group characteristics (e.g. a bus tour group or a young couple), the moods of the individuals involved and how extroverted or introverted the culture or individuals within the culture are.

As we have seen, some supporters of the advocacy platform argue that direct contact can dissolve stereotypes, but it can alternatively make the situation even worse under certain circumstances — for example, when the contacts are overly intrusive and extend into backstage areas. Conversely, problems can also result when tourists 264are channelled into exclusively tourism-focused spaces such as retail frontstages or enclave resorts (see chapter 8). Accusations may arise in such cases that the tourists are monopolising the most desirable spaces, that they are being deliberately snobbish or that small operators are being denied the opportunity to engage tourists in commercial transactions. Further, the reduction in direct contact that results from these attempts to remove tourists from local areas may indeed reinforce the cultural stereotypes that each group holds about the other. This discussion illustrates the paradox of resentment that is faced by tourism managers, wherein tensions can be generated whether destination managers choose to maximise contact between tourists and locals through a strategy of dispersal or to minimise these contacts by pursuing a policy of isolation or containment.

High proportion of tourists relative to the local population

Where the number of tourists is high compared with the resident population, the former may be perceived as a threat that is ‘swamping’ the destination. Again, the influence of other variables should be considered, as the perceived number of tourists may be inflated by their cultural or racial visibility, or by their concentration within confined boundaries of space or time. An excellent example of this phenomenon occurs in the cruise ship industry when large numbers of passengers are discharged into a port of call. These excursionists tend to concentrate within restricted shopping areas in the central business district for a short period of time, and are usually unaware of and unprepared for the actual sociocultural conditions prevailing in the destination.

Hyperdestinations are the extreme expression of the spatial and temporal distortions that emerge in most tourist destinations under free market conditions (see chapters 4 and 8). The situation is especially acute in tourist shopping villages, on small islands and in remote villages, where even a small number of tourists can be overwhelming. For this reason, managers should be extremely careful about placing too much reliance on ratios that measure the number of locals per tourist or visitor-night over an entire country or state. For example, for Australia as a whole, there were about four residents for every inbound tourist in 2013. However, this statistic is rendered almost meaningless because the number would be much lower for an area such as the Gold Coast (and would vary considerably between the coastal and inland suburbs and between summer and winter), and much higher in inland farming areas.

Rapid growth of tourism

If tourism is growing at a rapid pace, the local society, along with its economy and culture, may not have adequate resilience to effectively adjust to the associated changes. For example, sufficient time may not be available to devise and formalise the necessary backstage/frontstage distinctions. The result can be a growing sense of anxiety and powerlessness within the local community. As with the tourist–host ratio factor, this issue is closely related to the size of the destination — even a small absolute increase in visitor numbers, or the construction of just one mid-sized hotel, can represent high relative growth that challenges the capacities and capabilities of a small destination.

Dependency

Problems are likely to occur if a destination becomes too dependent on tourism, or if the sector is controlled (or is perceived to be controlled) by outside interests. In the first scenario, sociocultural problems occur indirectly as seasonal or cyclical fluctuations in demand generate widespread unemployment or, alternatively, an influx of outside workers (see chapter 8). High levels of control by outside forces, as per the second scenario, are problematic for several reasons, including resentment over the 265repatriation of profits and monopolisation of high-status jobs (e.g. hotel managers and owners) by nonlocals. In addition, locals may feel that they are not in control of events that affect their everyday lives. This sense is reinforced by the increased power of large transnational corporations, the instability of small local businesses, and the uncertainty associated with globalisation (see chapter 5).

Different expectations with respect to authenticity

Cultural differences notwithstanding, tourist–resident tensions arise if there is a misunderstanding about the status of a cultural performance or other tourism products in terms of their perceived ‘authenticity’. On one level it can be argued that everything, including fake copies of local art, is ‘authentic’ or ‘genuine’ because of the simple fact that it exists and conveys a meaning of some kind. However, this view is not helpful, since the concept can then no longer be used to distinguish between different tourism products and experiences. A more conventional view is to consider authentic goods and experiences as those that embody the actual culture (past or present) of the destination community. However, even this is problematic. In the example of the Native American artists noted earlier, is the nontraditional culture that is being practised in the backstage, which represents the contemporary reality of that group of people, any less authentic than the tepee displayed in the frontstage?

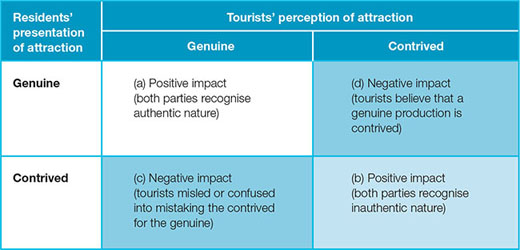

One way of approaching the issue is to consider perceptions of authenticity. Four generalised scenarios are possible, as depicted in figure 9.4. In the first scenario, (a), the attraction is presented as authentic and is perceived as such by the visiting tourist. This is the ideal option that is likely to characterise the first two stages of the commodification model outlined earlier. The opposite situation, (b), is also benign in terms of its implications for host–guest relationships. In this scenario, a performance is presented as contrived and is perceived as such by the tourists. While a philosophical argument can be made as to the inherent value or legitimacy of a contrived product, the crucial point is that both parties recognise and accept this contrived status. There is no attempt at deception, and no fundamental misunderstanding among most participants. Disneyworld and Las Vegas are classic examples of venues hosting ‘doubly contrived’ attractions. In these fantasy worlds, no one believes, or is seriously deceived into believing, that the Magic Kingdom or the Excalibur casino are ‘real’ — everyone accepts that these are frontstage fantasy environments designed to attract and entertain tourists.266

FIGURE 9.4 Resident tourist cross-perception of attractions

The remaining two scenarios (c) and (d) are discordant and hence more problematic. In scenario (c), the performance is contrived, but tourists believe, through inadvertent (e.g. frontstage is confused with or misinterpreted as backstage) or deliberate reasons (e.g. frontstage is deliberately purveyed as backstage or the two are mixed), that they are viewing something that is genuine. The limbo performance in a Caribbean hotel, the sale of ‘genuine’ religious artefacts at Lourdes and the ‘greeting’ given to visitors by ‘native’ Hawaiian women, are all examples of this perceptual discord. Tourists may emerge from such experiences feeling cheated, embarrassed or exploited. MacCannell (1976) describes as ‘staged authenticity’ the deliberate attempt to convey contrived culture as authentic.

The opposite situation, (d), occurs when the performance is genuine, but tourists see it as contrived, possibly because of scepticism obtained from previous experience with scenario (c). Residents may be offended when tourists react to a sombre local ceremony, for example, in a disrespectful or flippant manner, as sometimes occurs in the religious events that are held during Carnival time in the Caribbean or Latin America.

Resident reactions

One effect of the cautionary platform was greater interest in the attitudes and perceptions of local residents affected by tourism-related activity. Early theories about this topic hypothesised that reactions to tourism were shared among members of the local community and that these attitudes tended to deteriorate as the level of tourism development increased (Weaver & Lawton 2013). Mounting empirical evidence, however, suggests a far more complex picture. In reality, any community is likely to display a diversity of reactions to tourism at any given stage of development, depending on such factors as the individual resident’s personality (e.g. allocentric or midcentric), their proximity to the tourism frontstage, the amount of time they have resided in the destination, their socioeconomic status and whether or not they are employed within the tourism industry. Social exchange theory holds that individuals base their support on the degree to which they perceive that the benefits of tourism to themselves and the wider community outweigh the costs (Nunkoo & Gursoy 2012). Alternatively or in conjunction, social representations theory contends that people make sense of the world around them, including tourism, through the shared meanings conveyed by the media, social reference groups, and personal experience (Pearce & Chen 2012). Accordingly, if your friends are opposed to tourism, you are more likely to be opposed as well.

The complexities inherent in the tourism assessment process give rise to complex structures of resident opinion. Typically, communities display a range of attitudes from strong support to strong opposition, with most residents falling in between these extremes. An example is provided by the Gold Coast, where about 15 per cent of surveyed residents in 2012 were strongly opposed to the annual Schoolies Week event, while an equal number were strongly supportive. The former regarded the event as a disruptive drinkfest while the latter perceived it as a legitimate rite of passage for students ‘letting off steam’ before entering their adult life. The remaining 70 per cent of residents were conditional, arguing essentially that most schoolies (high-school graduates) were well behaved and that most problems were caused by a few troublemakers, many of them non-schoolies. They argued that Schoolies Week was fine as long as the festivities were contained both in space and time, and troublemakers apprehended and punished (Weaver & Lawton 2013). Community 267support for tourism or specific tourism attractions in most destinations ultimately depends on the strategies and measures taken to ensure that negative impacts are minimised (as for example through development restrictions, zoning, quotas, tourist education programs, infrastructure improvement, limits on non-local ownership, demarketing of undesirable segments) and positive impacts maximised (as for example through beautification programs, revenue-sharing, creation of good jobs for locals). Even among relatively ‘powerless’ groups such as indigenous people, successful adaptation to increased levels of tourism development is a common phenomenon (Weaver 2010b) (see Contemporary issue: Resilient rural renegades in northern Vietnam).

contemporary issue

![]() RESILIENT RURAL RENEGADES IN NORTHERN VIETNAM

RESILIENT RURAL RENEGADES IN NORTHERN VIETNAM

Indigenous people account for about one-half of the 200 million people who live in the uplands of the South-East Asian peninsula. As governments in China, Vietnam and Laos initiate programs to integrate these peripheral regions into their respective national economies, indigenous residents are being forced to alter their traditional ways of life and adjust to new economic realities. An actor-oriented livelihood approach, which maps information flows and relationships among stakeholders (actors) to inform reflection and action, was taken by Turner (2012) to understand how the indigenous Hmong of northern Vietnam negotiated this new economic landscape. Proving to be anything but powerless pawns, the Hmong coped by taking advantage of a number of opportunities. For example, they continued to cultivate an extremely diverse array of traditional and hybrid crops, raise livestock, and gather forest products. However, in response to consumer demand from China, Hmong farmers have also learned to cultivate the spice black cardamom — a valuable cash crop that does not compete with other crops in the farming calendar. When there was governmental encouragement to develop tourism, Hmong women saw an opportunity to sell their colourful textiles to tourists, as they had done during the era of French colonisation before the 1960s. These textiles can be described as ‘pseudo-traditional’ clothing that is especially attractive because it combines traditional and modern design. Some Hmong women also work as freelance trekking guides, having picked up excellent English in their encounters with tourists in the major regional town of Sa Pa. With a diverse choice of economic options and a reputation for ‘working around the rules’ if necessary, the Hmong are resilient rural renegades who maintain sustainable livelihoods on their own terms. They are able to shift from one opportunity to another as circumstances warrant, balancing between the formal and informal economies while maintaining the integrity of their traditional culture. While tourist income is desired and realised opportunistically, the Hmong do not consider it indispensible.

268

ENVIRONMENTAL BENEFITS

ENVIRONMENTAL BENEFITS

Various environmental benefits have been cited by the advocacy platform as a supplement to the dominant economic benefits. First, whatever specific attractions a destination offers, clean and scenic settings are desirable assets for attracting most kinds of tourist. Destination managers therefore have a permanent incentive to protect and enhance their general environmental assets. Specific events can stimulate this incentive, as when major efforts were made by the Chinese government to reduce air pollution in Beijing during the 2008 Summer Olympic Games so that tourists would not leave China with a negative image of the country (Streets et al. 2007). Second, a relatively unspoiled natural environment is itself a primary attraction in sectors such as ecotourism. It is often the case that the revenues obtained from ecotourism are greater than what could be obtained alternatively from the use of the same land for agriculture or logging, so this creates a strong incentive for its preservation as natural habitat (see chapter 11). Finally, people who experience protected areas and other natural habitats first-hand are often more willing to support the preservation of that land through donations, volunteering and political or social activism. They may also become more sensitive to broader environmental issues. In one sample of ecolodge guests in Lamington National Park, Queensland, 83 per cent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that their personal exposure to the national park had made them more conscientious about the environment in their everyday lives (Weaver & Lawton 2002).

ENVIRONMENTAL COSTS

ENVIRONMENTAL COSTS

Since 1950, the tourism industry has demonstrated a remarkable capacity to intrude on, and sometimes overwhelm, certain kinds of physical environment, thereby providing contrary evidence to the earlier argument that tourism protects such environments from less benign forms of use. Of particular concern is the effect of 3S tourism on coastal areas, inland bodies of water, the seas, and cruise ship ports of call (see the case study at the end of this chapter). Because of market demands, the developers of 3S accommodation and other tourism facilities try to locate as close as possible to water-based attractions. However, ironically, these high-demand coastal and shoreline settings are also among the most complex, spatially constrained and vulnerable of the Earth’s natural environments. In effect, the greatest concentrations of leisure-based tourism activity have been established, within an exceptionally short period of time, in the very settings that are least capable of accommodating such levels of development, leading to situations of continual conflict between people and the natural environment (see Technology and tourism: Coping with sharks in Western Australia).

The sprawling and ever expanding coastal resort agglomerations of eastern Florida, the Riviera, the insular Caribbean and south-east Queensland all demonstrate this dilemma. On a smaller scale, a similar problem is being experienced in fragile mountain environments such as the European Alps, the Australian Alps, the Himalaya and the Rockies (Kessler et al. 2012). Small islands are also highly vulnerable because of their limited environmental resource base, and the fact that just one or two major resort developments can impact on a significant proportion of the total environment. A great problem for tourism is that environmental deterioration, like cultural commodification, may progress to a state where visitors are no longer attracted to the destination — and the destination is then faced with the double dilemma of a degraded environment and a degraded tourism sector (see chapter 10).269

technology and tourism

![]() COPING WITH SHARKS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA

COPING WITH SHARKS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA

Several surfers are killed by sharks each year in Western Australian waters, and the state is considered to be one of two world shark attack hotspots (FMNH 2013). Because such attacks generate periodic bursts of negative media publicity that cause some consumers to form a negative destination image, the state government has issued orders to kill sharks that pose an ‘imminent threat’ to humans. The move was supported by many surfers and operators of tourism businesses (Al Jazeera 2012). The Western Australian government also wants the Commonwealth to remove the great white shark — which is classed as ‘vulnerable’ — from the protected species category in order to facilitate this aggressive management response and thereby encourage continued tourism development. Environmentalists counter that the real problem is the relentless encroachment of humans on the habitat of sharks, whose feeding grounds have been forced closer to shore by climate change. A related issue is the dramatic decline in world shark populations, 70 million of which are killed each year by humans (Casey 2012). One low-tech solution, the placement of shark nets, traps other marine species and is not practical for certain beach settings. In Western Australia, the government’s $7.12 million package to address the shark issue funds not only the killing of sharks, but also aerial patrols (to provide warning) and tagging to better understand shark mobility (Al Jazeera 2012). The use of electronic shark deterrent technologies to reduce the number of attacks is another potential solution being investigated (Oceans Institute 2013). Electronic shark deterrents are devices attached to swimmers and surfers that emit electrical pulses to create an unpleasant sensation in the nasal receptors sharks use to sense the presence of food. The muscular spasms the devices cause do not harm the shark, but they are enough to compel it to flee. Because of the power of the electrical current, such devices are not considered safe for children under 12 or people with serious health conditions. Appropriate applications mean that the sharing of a common habitat by sharks and humans without harm to either is a reasonable possibility, especially as improvements in the technology will likely facilitate participation of young children and people with serious health conditions.

Environmental impact sequence

In the late 1970s the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD 1980) formulated a simple and still relevant four-stage environmental impact sequence, which uses a systems approach to model the environmental effects associated with tourism (see figure 9.5):

stressor activities initiate the environmental impact sequence

environmental stresses associated with these activities alter the environment

environmental responses occur as a result of the stresses; these can be immediate or longer term, and direct or indirect

human responses occur as various stakeholders and participants react to the environmental responses; these can also range from immediate to long term, and from direct to indirect. These responses, notably, may themselves be new stressor activities that trigger new environmental stresses and responses.

270Four categories of stressor activity (‘permanent’ environmental restructuring, generation of waste residuals, tourist activities and indirect and induced activities), as described in the following subsections, account for all such impacts.

‘Permanent’ environmental restructuring

This category encompasses environmental alterations directly related to tourism that are intended to be permanent. Associated stressor activities include the construction of specialised facilities such as resort hotels and theme parks, as well as tourist-dominated golf courses, marinas and airports. Focusing on the construction of a new resort hotel, the following list indicates just some of the possible site-associated environmental stresses:

clearance of existing natural vegetation to make way for structures, roads and parking areas

removal of coral to create a passage for pleasure boats

selective introduction of exotic plants to create aesthetically-pleasing landscaping

levelling of dunes and other terrain to facilitate construction

reclamation of natural wetlands such as mangroves or estuaries to expand development footprint

sand mining on local beaches to reduce costs of importing construction materials

extraction of groundwater to supply structures.

The potential environmental responses to clearance include the reduced biodiversity of native flora and fauna and increased numbers of undesirable and opportunistic exotic plants and animals. Levelling is commonly associated in the short term with soil erosion and landslides, and in the longer term, particularly in more distant locations, with flooding problems due to increased run-off and the raising of streambeds by the downstream deposition of sediments. Also note that sand mining may be carried out at 271a considerable distance from the actual development site. It is important to stress that environmental responses are not restricted to the site where restructuring is occurring, but can be realised in faraway locations. This can be problematic for a destination that is itself well managed, but suffers the effects of poor management within, say, an upstream destination that discharges untreated wastes into the river shared by both destinations.

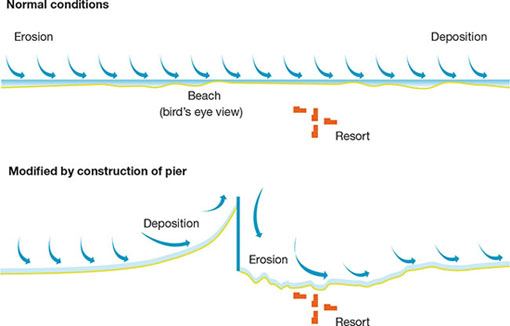

In coastal areas, an adverse environmental impact sequence that interferes with normal geophysical processes is the construction of beach piers to accommodate watercraft. Under normal conditions, the long-term stability of the beachfront is maintained as sand particles removed by lateral offshore currents are replaced by new material eroded from nearby headlands or other beaches and are deposited elsewhere by this same current (see figure 9.6). The effect of constructing a pier (i.e. the environmental stress) is to interrupt this pattern, causing sand to pile up behind the pier in a spit-like formation. Lacking replenishment by this sand, the beach on the other side of the pier is eroded by the modified current. This eventually eliminates portions of the beach, and threatens adjacent resorts and other structures. Possible human responses in the short term include reduced visitor numbers in the eroded beach environment, which would lead to a loss of income in the adjacent resorts. The resort owners could respond by constructing their own small pier to trap sand in front of the resorts. In the longer term, the facilities might have to be abandoned if no countervailing measures are undertaken. Remedial measures relevant to this or other coastal development scenarios include the removal of the pier, the pumping of sand across the pier from the artificial spit to the down-current beach, or the construction of an offshore artificial reef to modify wave action. Each of these options, however, entails its own significant costs and benefits.

FIGURE 9.6 Environmental impact sequence involving construction of a pier

Generation of waste residuals

Waste residuals in tourism typically include the following:

blackwater (i.e. raw sewage) and greywater (e.g. water from showers and kitchens)

atmospheric emissions from aircraft, tourist vehicles, lawnmowers, generators and air-conditioners

noise from aircraft and vehicles

run-off of fertilisers and pesticides from golf courses and lawns.

Focusing on the first of these stressor activities as an example, blackwater is a significant environmental stress when it is discharged in large quantities directly into a nearby body of water or into a local water table. Environmental responses will probably include localised water contamination, the harming or killing of marine life and a loss in aesthetic appeal. Initial human responses, which include various health problems, will likely lead to reduced visitation unless steps are taken to deal with the problems through the elimination or reduction of the waste itself, or better containment or treatment of the emissions.

In recent years, the issue of atmospheric emissions has been strongly framed by the phenomenon of climate change, which is the gradual increase in global surface temperatures that is widely attributed to the release of so-called ‘greenhouse gases’ by human activity. These increases are expected to have significant negative consequences for many vulnerable locations, and at best inject a high degree of uncertainty into future climate and weather patterns worldwide (IPCC 2014). By some estimates, the global tourism sector accounts for around 5 per cent of all such emissions, symbolised perhaps most cogently by the airline industry (Becken & Hay 2012). Tourism-related human responses to climate change have mitigation as well as adaptation components, and the extent to which one or the other is pursued depends largely on the severity and imminence of the expected impacts.

With respect to adaptation, pleasure periphery destinations in particular have been implicated as sites of high concern given that coastal environments, along with alpine areas, are expected to be among the environments most impacted by the effects of climate change. This will likely occur through rising sea levels, increasingly intensive and more numerous storms, and groundwater contamination in the first case, and through the loss of snow cover in the second (Becken & Hay 2012). Adaptation includes the adjustments that are made in response to such perceived threats by industry (e.g. stronger building codes for seaside hotels, alternative activities for longer off-seasons in ski resorts), but also the decisions made by potential tourists. Consumers, for example, may believe media reports that the Great Barrier Reef is dying due to higher water temperatures, and decide instead to visit cooler water reefs in higher latitude locations. In such a case, industry adaptation must then also include public education and/or investment in destinations adjacent to more resilient coral populations or higher altitude snowfields. One important implication of climate change is that destinations can potentially be devastated by this global process regardless of how environmentally sustainable they are at the local level. Climate change may prove in coming years to be the ultimate test of resilience for many low-lying and alpine destinations.

Tourist activities

There is a relatively large body of literature on the effects of tourist activity on various natural environments (Buckley 2004; Newsome, Moore & Dowling 2013). Associated stressor activities in tourism include:

walking on coral reefs

disturbing aquatic sediments by divers and boaters

trampling vegetation

approaching wildlife

pedestrian or vehicular traffic congestion

consuming food and other resources

elimination of bodily wastes directly into water or soil.

While some of the environmental stress results from actions of a deliberately destructive nature (e.g. littering, harassment of wildlife or destroying vegetation with an off-road vehicle), apparently benign acts also cause damage when their cumulative impact exceeds local environmental carrying capacities. Examples include trail erosion and disruption of wildlife resulting from too much hiking or wildlife-viewing activity. Even more insidious is the inadvertent introduction of potentially harmful pathogens into remote areas by hikers, backpackers and other tourists. Buckley, King and Zubrinich (2004), for example, describe how spores of the jarrah dieback pathogen (Phytophthora cinnamomi), which can destroy 50–75 per cent of plant species in some Australian plant communities, are readily dispersed by off-road vehicles, trail bikes, mountain bikes, hiking boots and horses. Solutions to contain this spread, such as the quarantine of unaffected areas or the complete sterilisation of all equipment, vehicles and clothing before entering such areas, are prohibitively expensive, excessive or basically ineffective. Another human response is to provide educational material to tourists, but a program to do so in Victoria to contain the spread of cinnamon fungus — another pathogen devastating to native vegetation — was unsuccessful. At the start of the program in 1993, 81 per cent of sampled park visitors were unaware of the fungus, and the figure was essentially unchanged at 83 per cent in a follow-up 2003 survey (Boon, Fluker & Wilson 2008).

In a coastal context, the negative effects of tourist activity on coral reefs are well documented and widespread (Cater & Cater 2007; Lück 2008). Notably, serious damage such as coral breakage is attributable mostly to inadvertent and often un-avoidable activities such as contact with fins and sedimentation caused by fin agitation (Poonian, Davis & McNaughton 2010). Such impacts can be only partially controlled by diver education and skills enhancement, and hence it is likely that increases in coral damage will be commensurate with increases in the amount of diving activity that occurs in a particular site.

Indirect and induced activities

In earlier discussions on tourism revenue and employment (see chapter 8), the concept of ongoing indirect and induced impacts was noted. A similar effect applies to the stressor activities associated with the environmental impact sequence. Road improvements or airport expansions that occur because of tourism are examples of indirect permanent environmental restructuring. Induced effects include the construction of houses for people who have moved into an area to work in the tourist industry, and amenity migrants who move to an area for lifestyle purposes after experiencing that area as a tourist.

The indirect and induced effects of tourism at a global scale are enormous, given the number of facilities that are at least partly affiliated with tourism, and the number of people who are employed in the tourism industry or are dependent on those who are. It is evident, for example, that most of the inland (and non-tourism oriented) suburbs of Queensland’s Gold Coast and Sunshine Coast would never have been developed had it not been for the presence of tourism as a propulsive industry and generator of regional wealth. However, as with revenue and employment, it is difficult to measure the extent of tourism-related effects on such ‘external’ environments when the interrelationship is not immediate and direct.274

Ecological footprinting

Increased concerns over climate change and other environmental impacts of tourism have prompted attempts to calculate the ecological footprint (EF) of various types of tourism activity. An EF is the measurement of the resource exploitation that is required and the wastes that are generated to sustain a particular type of tourist or tourism activity, such as an aeroplane trip, festival, or stay in a resort hotel (Filimonau et al. 2011, Hunter & Shaw 2007). An increasingly popular subtype is the carbon footprint, which focuses on the greenhouse gases generated by such activity. The purpose of ecological footprinting is firstly to identify with as much precision as possible the resource and waste implications of the target activity over time, and then to use this information to generate awareness of the problem and devise appropriate mitigation responses. Given the complexity of tourism systems, it is not surprising that EF is an imperfect science, especially if the sponsoring body intends to take into account the indirect and induced impacts of tourism, as well as the normal residence footprint that is temporarily eliminated when one travels. Nevertheless, well-developed EF indices are effective in confronting consumers and businesses with seemingly convincing evidence of their environmental impacts, and thereby increasing the likelihood of some kind of mitigating action.

Management implications of sociocultural and environmental impacts

All deliberations on impact — whether environmental or sociocultural — should be informed by the following critical observations:

All tourism-related activity causes a certain amount of stress, and this stress is likely to include both positive and negative effects for different stakeholders. At any stage of tourism development, an affected community will display a very diverse range of attitudes toward tourism, and a majority of residents will usually recognise the existence of concurrent benefits and costs.

The critical issue therefore is not whether stress can be avoided altogether, but whether the net effects are acceptable to most residents or can be reduced to an acceptable level through proactive management strategies, including trade-offs between costs and benefits, and personal or collective adjustment strategies. Acceptability is fundamentally influenced by the perception of benefits received — residents normally try to realise optimum benefits, but a high level of environmental or sociocultural stress may be tolerated in exchange for significant job and revenue opportunities for the local community. It may also be reasoned that the negative environmental or sociocultural impacts of tourism are less than those that would result from alternative economic activities such as logging.

Stress is linked to carrying capacity, which varies from site to site, and is a malleable concept that can be manipulated through site hardening, the formal designation of frontstage/backstage distinctions and other adaptive measures. Ecosystems, as with cultures and societies, have different levels of resilience and adaptability. Thus, a concentration of 500 tourists in a closed-canopy temperate forest would probably have no discernible impact on that environment, but could seriously disrupt an Antarctic site. However, even within the same type of environment (e.g. a tropical rainforest or a coral reef), site-specific carrying capacity will be influenced by variables such as slope, biodiversity, soil type and hydrology. Generalisations about carrying capacity should, therefore, be made with great caution.275

Finally, carrying capacities are often extremely difficult to identify, since stress and its impact are not always dramatic and site-specific — that is, they can be incremental, long term or evident in places far removed from the site. A large resort destination such as the Gold Coast may appear to be functioning within local environmental carrying capacities, until a 100-year cyclone event destroys the community because of alterations to the protective dune and estuarine environments that occurred over previous decades. Similarly, a local community may appear to be coexisting peacefully with an adjacent enclave resort, until one particular incident triggers a violent community-wide reaction against that resort. As discussed in more detail in chapter 11, a strong element of uncertainty and ambiguity must always be taken into account when attempting to identify the long-term costs and benefits of tourism in any destination.

Resilience is perhaps the most important attribute for destinations, communities, families and individuals to acquire, so that they can maximise the benefits and minimise the costs of inherently complex and unpredictable tourism systems.

276

CHAPTER REVIEW

This chapter has considered an array of sociocultural and environmental impacts potentially associated with the development of tourism. The major sociocultural benefits involve tourism’s potential to promote cross-cultural understanding, to function as an incentive to preserve a destination’s culture and historical heritage and to foster wellbeing and stability within the local society. These advantages were cited by the advocacy platform as secondary benefits to the all-important economic consequences. Sociocultural costs, as emphasised by the cautionary platform, can occur through the gradual commodification of culture. Commodification occurs when the local culture becomes more commercialised and modified, as local residents respond to the opportunities provided by the increased intake of visitors. Prostitution is a one extreme of this process. Other aspects involve the sociocultural consequences of the tourism demonstration effect, and the direct and indirect connections between tourism and crime, wherein tourists and residents can both be victims or perpetrators.

Negative sociocultural impacts that may eventually breach a destination’s carrying capacity are more likely to occur in a destination when there is inequality in material wealth between the residents and tourists, strong cultural differentiation and a tendency on the part of tourists to adhere strongly to their own culture. Other factors include tourist–resident contacts that are overly intrusive or exclusive, the extent to which residents are able to differentiate between ‘backstage’ and ‘frontstage’ spaces, a high proportion of tourists to residents, an overly rapid pace of tourism growth, a level of dependency on tourism and external control over the same, and differential expectations as to the meaning and authenticity of cultural and historical products. Resident reactions to increasing tourism development — formerly regarded as a simple and collective linear progression from euphoria to antagonism — are complex, with data indicating that communities hold diverse and often ambivalent perceptions about tourism at all stages of development. These perceptions largely depend on the degree to which individuals perceive benefits and costs from tourism, and are influenced by media, other social reference groups or personal experiences. Residents, in most cases, have considerable capacities to pre-empt or change inappropriate tourism activity, or to adapt accordingly.

The main environmental benefit associated with tourism is its provision of incentives for the protection of natural resources that would probably otherwise be subject to less benign forms of exploitation. However, the environmental impact sequence suggests that tourism development itself may produce negative consequences. This sequence is a four-stage process involving the appearance of stressor activities, environmental stresses that result from these activities, environmental responses to those stresses and human reactions to the responses. The four inclusive categories of stressor activities are permanent environmental restructuring, the generation of waste residuals, tourist activities and indirect and induced activities associated with tourism. Empirical evidence for topical phenomena such as climate change suggests that these impacts can often be subtle, indirect, delayed and evident in regions far removed from the location of the original stress, thereby making the calculation of applicable ecological footprints a complicated process.

SUMMARY OF KEY TERMS

SUMMARY OF KEY TERMS

Amenity migrants people who move to an area because of its recreational and lifestyle amenities, including comfortable weather and beautiful scenery; amenity migrants are usually first exposed to such places through their own tourist experiences277

Backstage the opposite of frontstage; areas of the destination where personal or intragroup activities occur, such as noncommercialised cultural performances. A particular space may be designated as either frontstage or backstage depending on the time of day or year

Carrying capacity the amount of tourism activity (e.g. number of visitors, amount of development) that can be accommodated without incurring serious harm to a destination; distinctions can be made between social, cultural and environmental carrying capacity, all of which can be adjusted with appropriate management

Climate change the gradual increase in global surface temperatures that is usually attributed to the excessive release of heat-trapping greenhouse gases through human activity such as the burning of fossil fuels; human responses are usually divided into distinctive adaptation and mitigation categories

Commodification in tourism, the process whereby a destination’s culture is gradually converted into a saleable commodity or product in response to the perceived or actual demands of the tourist market

Ecological footprint (EF) the measurement of the resources that are required and wastes generated in sustaining a particular type of tourist or tourism activity

Environmental impact sequence a four-stage model formulated by the OECD to account for the impacts of tourism on the natural environment

Environmental responses the way that the environment reacts to the stresses, both in the short and long term, and both directly and indirectly

Environmental stresses the deliberate changes in the environment that are entailed in the stressor activities

Frontstage explicitly or tacitly recognised spaces within the destination that are mobilised for tourism purposes such as commodified cultural performances

Gross national happiness (GNH) an index used officially by the government of Bhutan to measure development, based on principles of equity, environmental sustainability, cultural preservation and good governance

Human responses the reactions of individuals, communities, the tourism industry, tourists, NGOs and governments to the various environmental responses

Paradox of resentment the idea that problems of resentment and tension can result whether tourists are integrated with, or isolated from, the local community

Social exchange theory the idea that support for tourism is based on each individual’s assessment of the personal and societal costs and benefits that result from this activity

Social representations theory the tendency of individuals to make sense of the world around them through the shared meanings conveyed by the media, social reference groups, and personal experience

Stressor activities activities that initiate the environmental impact sequence; these can be divided into permanent environmental restructuring, the generation of waste residuals, tourist activities and indirect and induced activities

Tourist–historic city an urban place where the preservation of historical districts helps to sustain and is at least in part sustained by a significant level of tourist activity

Volunteer tourism a form of tourism involving extended visits to places where the volunteers assist with designated aid or research projects

QUESTIONS

QUESTIONS

Is it naïve to believe that tourism functions as a force for world peace? Explain your reasons.278

-

Is commodification always a negative impact of tourism for destinations? Why?

What strategies can a destination adopt to minimise its negative effects while maximising its benefits?

-

How can the demonstration effect indicate both the weakness and strength of the individual or society in which it is occurring?

How could destination managers mobilise the demonstration effect so that it has positive effects on the society and culture of the destination?

Is an allocentric tourist more likely to be the victim of crime in a destination than a psychocentric tourist? Explain your reasons.

-