1. Destroying the Four-Generation Myth

You’re forgiven if you’ve gotten tired of hearing about generational issues in the workplace. Amazon lists more than 1,100 books with the words generation and workplace in the title. That’s the equivalent of a new book on generational issues in the workplace being published every 6½ days for the past 20 years. If you’re fatigued, it’s because you should be. Talking about the same issue in the same way and with the same language over and over and over again is exhausting.

Indeed, it’s precisely because of this avalanche of literature that I’ve been compelled to write this book. The way we have been thinking about generational differences in the past two decades—the central premise behind those 1,100 books and the uncountable others with cleverer titles that talk about the same thing—is making it harder for us to find workable solutions. We’ve been complicating the problem rather than solving it.

Fortunately, things are much easier than they seem.

It’s not that there aren’t significant differences between generations; there are. For example

• You might have grown up listening to record albums—and not as an accoutrement to your retro lifestyle but because it was the only form in which music came. If you did, it’s possible you also grew up drinking phosphates, lounging on the davenport, wearing derby hats, and hoarding lamp oil.

• You may never have seen a pay phone. Perhaps you wonder if they were phones that paid you.

• You may have all but forgotten that the English language has vowels and rules for proper spelling, and that thngs r rlly hrdr if u brk th roolz all th tim.

• You might have grown up without the Internet, which necessarily means you spent your entire childhood being bored. What did you do for fun? Nobody knows.

• You might still have a fake ID in your dresser.

• You might have fake teeth sitting on your dresser.

• You might have children who learned things in fifth grade that you yourself didn’t learn until high school or college.

• You might be worried about your pension.

• You might not be quite certain what a pension is—or, more accurately, what a pension was.

It’s a safe bet that some of these descriptions remind you of you, and some of them make you shake your head at the people to whom those descriptions apply. We are undoubtedly different. But we’ve allowed ourselves to categorize those differences in a thoroughly unhelpful way. We take as axiomatic the following sentence:

For the first time in history, there are four distinct generations operating side by side.

Every speaker, book, lecture, infographic, or TED talk that addresses generational issues is founded on the premise of this four-generation workplace. It’s so ubiquitous that you’ve probably never questioned it. Instead, you’ve asked yourself, “How am I supposed to get anything done when there are so many people with so many different needs, motivations, desires, goals, and issues? How can I balance all these conflicting desires against each other in a way that works for everyone and somehow doesn’t consume my every waking thought?”

Again, if you have ever felt overwhelmed by the multigenerational workplace, it’s not your fault. You’ve simply been persuaded by an endless stream of “generational experts” telling you how crazy and difficult and unprecedented the working world is today. In fact, some of them want you to feel overwhelmed. They want you to be scared. That’s how they sell you things: by making these issues seem bigger than they really are and then offering “solutions” to those artificially inflated problems.

But not me. I don’t want you to be scared, except maybe of sharks and botulism and close talkers and other things it makes sense to be scared of. When it comes to your career, however, I want you to feel secure. The challenges facing today’s workforce are not unprecedented. In many ways, they are the same challenges that have been facing professionals for centuries.

The point of this chapter is to banish once and for all the notion that there are four generations in today’s workplace. The four-generation model is entirely unworkable if you want to create loyalty, dedication, and runaway success. Thinking of your workforce as multigenerational creates more problems than it solves. Fortunately for us, there are not four generations operating side by side. That’s a lie whose time has come, and this book is going to bury it once and for all.

Generational Differences Throughout the Ages

Strictly speaking, the length of a generation is the amount of time it takes for an infant to get old enough to have children of his or her own. Historically this has ranged anywhere from around 13 years (please don’t have kids when you’re 13, by the way) up to 40 years—although it’s hard to say exactly how our ancestors measured the length of a generation because there’s decent evidence to suggest that nobody paid it even the slightest amount of attention. I’ve typed every possible permutation of “generational differences” into every search engine there is,1 and there are exactly zero mentions of generational differences being an issue that anyone talked about in any form whatsoever before about 1960.

1 Except Bing. But I’m not counting that against me.

This means that for the majority of human history, generational differences either didn’t exist (which is seriously unlikely) or were framed in different terms (which we’ll be discussing in greater detail shortly).

The most common argument used to explain why we have a four-generation workforce for the first time in human history is that—you know what’s coming, don’t you?—the world today is different than it used to be. These are the two platitudes we always trot out when discussing generational issues: For the first time in history, there are four distinct generations operating side by side, and the world today is different than it used to be. But let’s put this into a proper perspective. The Revolutionary War was as comprehensive and world-altering for early Americans as WWII was for the so-called Silent Generation; the French and Russian revolutions were significantly more volatile and transformative than the 1960s and Vietnam were for the Baby Boomers; and the printing press was easily as colossal a technological innovation for 15th- and 16th-century Europeans as the Internet has been for today’s Generations X and Y (and the rest of us, too). There is nothing so unique about our world today that we can’t find parallels from earlier eras. And yet our ancestors didn’t talk about the travails of negotiating a multigenerational workforce, and we do.

To be sure, people tended not to live as long as we do today (yay for toilets and medicine and antibacterial soap!), so there would have been fewer instances of 20-year-olds working alongside 40- and 60- and 80-year-olds. But it certainly happened. For example, the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence ranged in age from 26 (Edward Rutledge, South Carolina) to 70 (Benjamin Franklin, Pennsylvania). In addition to them, there were 2 other signers in their 20s, 17 in their 30s, 21 in their 40s, 8 in their 50s, and 6 in their 60s. By today’s measure, these men would absolutely represent a multigenerational workforce, and yet none of them ever made mention of thinking along those lines, despite the fact that many of them were both business owners and prolific writers. Neither did a single factory owner in the first 200 years after the start of the Industrial Revolution. No one ever talked about a multigenerational workforce—not once—until 40 or 50 years ago.

So what happened?

The answer, which will surprise you for only a moment if indeed it surprises you at all, is that we have changed the way we market ourselves. Over the past several decades, marketers have systematically worked to create a hyper-complicated picture of our generational differences, specifically so that they could sell “solutions” in the form of books, products and consulting, and a host of other services.2 Today’s “multigenerational workforce” is not a real issue; it’s a marketing strategy. And I’ll prove that in the next few pages.

2 By the way, you’re totally forgiven right now if you think I’m being hypocritical. After all, I’ve written a book about this very subject, so maybe you think I’m the same as everyone else. But I promise that’s not true. I’m trying to simplify this issue, not add to the confusion. My goal is to make this book the last word on generational issues that you ever have to read. I don’t plan on writing another book about generational differences in the workplace because my goal is to ensure that by the end of this, you’ll realize that there’s really nothing else to say. I want to kill the industries that thrive on creating artificial generational differences, not help expand them.

How Marketing Created the “Multigenerational Workforce”

When the Industrial Revolution really got going, it didn’t take the producers of goods and services very long to figure out that they needed to have markets in which to sell those goods and services—and the more markets they could find, the more goods and services they’d be able to sell. So they hired marketers to go around inventing new markets.

And those marketers were very, very successful:

• George Frederick Earnshaw, president of Earnshaw Knitting Company in Chicago, published the children’s wear industry’s first trade journal in 1917, titled The Infants’ Department. Its aim was to help clothiers increase their sales by targeting infants as a distinct market, which had previously been an ill-defined or non-existent demographic.

• The term toddler was coined to describe a distinct demographic around 1936 to distinguish between infants and children—again as a way to sell more clothes.

• In 1997, the book What Kids Buy: The Psychology of Marketing to Children identified the tween as a demographic distinct from childhood and adolescence and, therefore, a new market for companies to target. (There’s a good chance, by the way, that the word tween was first used by J.R.R. Tolkien to describe hobbits. In case you, like me, find that kind of thing interesting.)

I could go on, but you get the point. As recently as a century ago, there were exactly three stages of life: infancy, childhood, and adulthood. Now, we’ve broken it down something like this:

• Infant—0 to 12 or 24 months.

• Toddler—1 to 3 years old, according to the CDC

• Child—3 to 10-ish years old

• Tween—8 to 12 years old (or 10 to 12, depending on the source)

• Junior teen—13 to 15 years old

• Teen—Technically 13 to 19 years old, but National Miss America says 16 to 18, and other groups have different age ranges

• Young adult—10 to 20 years old, or 12 to 18, or 14 to 21, or even 20 to 40 if you go by Erik Erikson’s stages of human development

That’s eight overlapping stages of life, and unless you go by Erik Erikson’s definition for young adult, we haven’t even made it out of college yet. If I kept going with all the stages of adulthood that we’ve created—young professional, parent, middle-aged, retired, old age, and so on—we’d easily get this list up to 15 categories. Is human life truly five times as complicated and nuanced now as it was a century ago? Or have we segmented ourselves into ever smaller cohorts in order to make it easier to target specific ideas, products, and services to particular populations?

We can also look at music. According to the Music Genres List, there are 23 types of rock music (acid rock, alternative rock, American traditional rock, arena rock, blues rock, British invasion, heavy metal, death metal, hair metal, gothic metal, glam rock, hard rock, noise rock, progressive rock, jam band, psychedelic rock, rock ‘n’ roll, rockabilly, roots rock, singer/songwriter rock, southern rock, surf rock, and tex-mex). I’m not sure many people would be able to describe the difference between hair metal and glam rock, and yet there are undoubtedly some music aficionados who would be quick to point out that some important genres are missing. And I haven’t even mentioned the 12 brands of country, or 16 genres of dance music and 14 flavors of electronic music, nor the fact that inside the alternative rock label there are 9 further divisions, each one more and more difficult to distinguish from the others. Dr. M. Duffett, commenting on Simon Reynolds’ analysis of indie music for The Guardian, puts it very well: “It is as if popular music criticism is now a laboratory which dissects the genetic codes of the tunes in order to guide packs of hungry consumers.”

The upshot of our relentless push toward more and more segmentation is that it has the tendency to make marketing easier but living harder. Take clothing, for example, which is really where this process began. We all know what section to visit in every store or on every website in order to find the things we want, and that’s enormously convenient. And at the same time, parents often lament that their children aren’t simply children anymore; now they belong to subcategories of childhood that seem to be changing on them every time they buy their kids a new outfit. That’s worse than inconvenient—it’s destructive. Today’s children are being placed into categories that didn’t exist for the parents who are raising them. Are children magically different today than they were in the 1940s or 1970s? Or are we making things more complicated than they need to be?

So How Does This Relate to the Generational Question?

I have no problem whatsoever with the marketing world’s tendency to create finer and finer consumer segments for the purposes of selling products. If a company knows its cameras are extremely popular with 23- to 27-year-old Irish men and creates commercials to attract this audience, that makes perfect sense. If a band bills itself as “countrified acid steampunk with a dash of EBM” and that somehow speaks to their audience, they should do what works.

But people aren’t products, and the generational question deals fundamentally with people and the interactions between them. Unfortunately, we’ve been segmenting various facets of society for marketing purposes for so long (toddler, teen, young professional, and so on) that we’ve extended the process to people themselves. The term Baby Boom was never intended to describe the personality of a generation but rather to indicate the explosion of births following World War II. It wasn’t until the 1970s that Baby Boomer assumed the connotation it has today; once it did, we became enamored of the belief that every new group of people was somehow fundamentally different than everyone who had come before or who would come after.

Again, this segmentation into Traditionalist, Boomer, Gen X, and Gen Y3 seems to satisfy our need to understand things. But the more segments we create, the harder it is for us to actually know what we’re supposed to do.

3 You’re now starting to hear some “authorities” describe a new generation, Generation Z, which is distinguished primarily as being “even more technologically oriented” than Generation Y. It seems that as we create more and more generations, we also require fewer and fewer distinctions between one generation and the next. Which begs the question—why are we bothering to create new generations in the first place?

There have been several interesting studies about this phenomenon, which for lack of a better term can be called the “poverty of choice.” Very basically, the hypothesis goes like this: The more choices we’re given, the more indecisive we become, and the more likely we are to do nothing. One of the classic examples of this phenomenon is the famous jam study of 1995.4 Researchers placed various jams in a display sample at a grocery store. Every few hours, they changed the number of offerings from 6 varieties to 24 varieties. On average, customers tried two samples at both the large and small displays. However, while more people stopped by the larger display (60% at the large display versus 40% at the small display), they made significantly fewer purchases (3% bought something at the large display versus 30% at the smaller display). Several other studies have been conducted with different products and different parameters, but the results tend toward the same conclusion: The more choices we’re given, the harder it is for us to know what to do with all those choices.

4 I’ll give you a pass if you’ve never heard of the famous jam study of 1995. It was called the “famous jam study” in the research I found. Fame, apparently, is a really, really subjective term.

And this is exactly what we’ve done with the generational question. In creating four distinct generations, we’ve made our workplaces seemingly easier to describe but actually harder to manage. If you’ve ever despaired of figuring out how to work with all the different kinds of people in your office or factory or secret laboratory at the center of the Earth or wherever you work, it’s because it feels like a problem too complicated to solve.

But it isn’t. We just need to return to thinking about generational issues in a simpler, more natural way—the way all of us did up until a few decades ago.

However, because you’ve been hearing about four generations since you’ve been old enough to care about generational issues in the workplace, let’s cover what you’ve heard before.

The Four (Totally Invented) Generations in Today’s Workplace

Following is a brief description of each so-called “generation.” I’ve taken the liberty of describing them in slightly different terms than you’re used to, but I think you’ll agree that my descriptions are not only accurate but also a whole lot more fun than what you’re used to reading. Here goes!

Generation #1: The Traditionalists—1922 to 1946

First we have the Traditionalists, also sometimes called The Matures, the Veterans, the WWII Generation, or the Silents. Whatever you decide to call them, they were born roughly between 1922 and 1946, which explains why they make fun of anyone who complains about the state of today’s economy. Their favorite medicines growing up were whiskey and cod liver oil, and many of them still maintain the belief that medicine can’t possibly be effective if it tastes like anything you would want to put inside you. Seriously, you could get them to eat sand if you told them it would promote their digestive health. They’re generally very loyal workers and good rule-followers, and their favorite pastimes are complaining about various physical ailments (often caused by eating too much sand) and yelling at children who run across their lawns, although sadly many of them now live in gated communities and so no longer have lawns to get mad at children for running across. To compensate for this, many of them now yell at their TVs instead. They always drive 18 miles an hour below the speed limit, and they let everyone know that they’re turning 7 miles before it’s going to happen and about 32 miles after completing the turn. If you’ve ever been caught behind a Traditionalist driver on the interstate in a single lane of traffic while the other lane is blocked off for the next 23 miles by orange construction cones, then you have a decent idea of what the afterlife is like if you don’t make it into Heaven. Traditionalists typically go to bed at 8 p.m., and every year their glasses get a tiny bit thicker. But don’t think they’re weak! This is the generation who decided three martinis for lunch was a good idea. They can drink the rest of us under the table. Don’t underestimate them.

Generation #2: The Baby Boomers—1946 to 1964

Next we have the Baby Boomers—or as I like to call them, the Dirty Filthy Hippies. Born between 1946 and 1964, they were the transitional generation between black-and-white and Technicolor. Instead of whiskey and cod liver oil, their favorite medicine growing up was LSD, which some of them actually tried to get added to our drinking water. They’re generally very goal-oriented and sometimes workaholics, which is hard to believe since many of them made it entirely through college without taking a shower. And how can I say that? Because the Baby Boomers were the first group of people since the Vikings to believe that razors and deodorant were somehow part of the oppressive establishment, which means they should have been barred from any decision-making position anywhere. They are notable for their conspicuous consumption and responsible for the absurdly optimistic phrase, “50 is the new 30!” which can be true only if you honestly expect to live to be 134 years old. They invented disco, for which they can never truly be forgiven. And perhaps most importantly, they also invented Generations X and Y, although many of them have tried to pretend that they had nothing to do with it.

Generation #3: Generation X—1965 to 1980

After the endless debauchery of the Baby Boomers came Generation X, so named because somewhere in the mid-1970s people apparently ran out of words. This is my generation of people, born between 1965 and 1980. We were famously called the “slacker” generation, which I personally find hilarious considering the generation that comes after us. In a radical departure from our forefathers, our favorite medicine is angst, which isn’t even a medicine—it’s just a whiny, pouty-faced way of looking at things. Our basic attitude is thus: “Show us your proudest accomplishment, and we’ll show you our crushing indifference.” We’re typically more informal than our elders and have an instinctive distrust for authority, which is hardly a new concept since “distrust of authority” is one of the foundational principles of the American psyche. We’re generally described as self-starters, and it’s quite evident that we weren’t interested in listening to anyone else when we created the fashion sensibilities of the 1980s, which could actually qualify as a crime against humanity. We are the reason for the hole in the ozone layer because we decided it was more important to have big hair than to avoid death by sunburn. Generation X was the first generation in the history of human beings to decide that nobody really understood us, including our friends and family, and that the less people understood us, the cooler we really were. There is really no good explanation for how any Gen Xers survived into adulthood, except that cynicism ultimately isn’t fatal. Oh, and we also gave the world rap music. You’re welcome.

Generation #4: Generation Y—1980 to Four Minutes Ago

And last but not least—in fact they’re the biggest generation in the country, slightly bigger than the Baby Boomers and about twice as large as my mopey Gen Xers—we have Generation Y, so named because by the mid-1990s people were too lazy to even care that X isn’t the first letter of the alphabet. They’re also known as Millennials—presumably because they were all born on the Millennium Falcon. Born between 1980 and four minutes ago, these people are barely old enough to shave. Their favorite medicine is Ritalin, which has probably been put into their cereal at this point. The proliferation of ADHD diagnoses has happened in large part because this generation, cognizant of the increasing cost of higher education, has chosen to get diagnosed with hyperactivity disorder so that they can pay for college by selling all their extra pills to their friends as “study aids.” They’re comfortable with new technologies and rapid change because they have never known a time without new technologies and rapid change. This is significant for three reasons. First, it means they’ve never developed film and been disappointed when 90% of their pictures turned out to be crap. Second, they’ve never made a mixtape for anyone, painstakingly arranging the songs in the proper order to best express their love for whoever they were going to give it to. And third and perhaps most importantly, they occasionally walk into trees and parked cars and walls and other people when they’re texting their friends because they can’t be bothered to watch where they’re walking. Seriously, they’re barely even people.

So there you have the four generations, as I like to think of them. Traditionalists, Boomers, Gen X, and Gen Y. That’s what you’ve heard. That’s the only version you’ve ever heard.

And it’s wrong.

The Two Major Problems with the Four-Generation Model

It would be natural to think that these four generational designations make sense. After all, we’ve been talking about the four-generation workplace for so long that it might be hard to think of it in any other way. You might be saying, “There really do seem to be significant distinctions between each of these groups of people.” And you’re right: There are significant distinctions between people. I’m not saying there aren’t. I’m just saying that those differences can be explained in much simpler terms than by putting everyone into one of four categories.

And here’s why. For one thing, there isn’t even much agreement on who belongs in which group. Depending on whom you ask, the Traditionalist Generation begins as early as 1909 or as late as 1925, and it ends sometime between 1940 and 1946. The earliest Baby Boomers were born as early as 1940 or as late as 1946, and they finished up either in 1960 or 1964. Generation Y is either the group of people born between 1980 and now, or it’s a much smaller group (say, between 1979 and the mid-1990s) so that we can apply the unfortunately fashionable Generation Z label to cover anyone born between the mid-1990s and today.

But in terms of imprecision, no “generation” is more obstinately unwilling to be pinned down than Generation X, for whom each of the following explanations has been used:

• Because Generation X is the tenth generation in America (This, by the way, isn’t at all true.)

• Because photographer Robert Capa used the term to describe people he was photographing in the 1950s (This means he was actually taking pictures of post-WWII Traditionalists or their Baby Boomer children.)

• Because of Jane Deverson and Charles Hamblett’s 1965 book Generation X (The authors were certainly interviewing people we would now call Baby Boomers.)

• Because Billy Idol was in a punk band called Generation X in the late 1970s, which was then referenced in Douglas Coupland’s 1991 book Generation X: Tales of an Accelerated Culture, as the genesis of the term (Huh?)

As you can see, Generation X is a term designed to apply to returning WWII vets, or British hippies, or Billy Idol, or the people we now consider to be Generation X. Even now the best that can be said of Generation X is that they were born sometime in the 1960s and stopped being born (depending on the source) in 1975, 1980, 1981, or 1982.

This is as close to a consensus as we’ve come, which isn’t much of a consensus at all. So the first problem is this: With such fluid designations, how are the millions of people on the edges of a given “generation” supposed to properly self-identify in order to know how to act and interact with others?

The logical counterargument to this criticism is that these years aren’t meant to be hard and fast. Instead, they’re supposed to function like convenient markers to make sense of the chaos. America didn’t suddenly crave independence and decide to go to war in 1776, but we use that year as an easy way to simplify the decades-long process that transformed America from a collection of subservient colonies into its own nation. In the same way, the argument goes, we’ve picked logical but admittedly arbitrary years to make it easier to talk about the different generations.

But this leads to the second and much, much larger problem with the four-generation model. Theoretically, the whole point in having a four-generation model is to make it easier for you to identify and then interact with people from different generations. However, it actually does the opposite. In an effort to justify that there really are significant and fundamental differences between the members of these four “generations,” people have created truly exhaustive lists that detail dozens of divergent qualities. I know you’ve seen those lists before (I’m going to reproduce one for you in couple pages, which I truly, sincerely hope you don’t take the time to read), and on most of them there is absolutely no overlap. On the lists where there is some overlap, it’s kept to a bare minimum in order to make each generation seem distinct from every other. As a result, the so-called four generations have been presented in a way that makes it look as though the people in each group are rigidly distinct in literally every way imaginable from the people in every other generation—all despite the fact that millions of people hover on the edges of these loosely defined categories and thus might be identified as completely different types of people, depending on which “generation” their age would assign them to.

So here’s what you’ve seen, I’m certain, in every book and keynote presentation about generational issues that you’ve ever endured. The author or presenter tells you for the millionth time in your life that for the first time in history, there are four distinct generations operating side-by-side in the workplace. He or she then goes on to outline the differences between those “generations.” This is the core of the book or presentation, designed to create order out of chaos. After this, you’re given various strategies to deal with members of each generation. I’m certain that every one of these authors and presenters is genuinely well intentioned and confident that their advice will be helpful to you. You’re then left to take that knowledge and put those strategies into practice. It sounds fairly simple.

But it’s not, because the charts they use to delineate their four-generation model make the entire picture too complicated for their well-intentioned advice to have any practical effect.

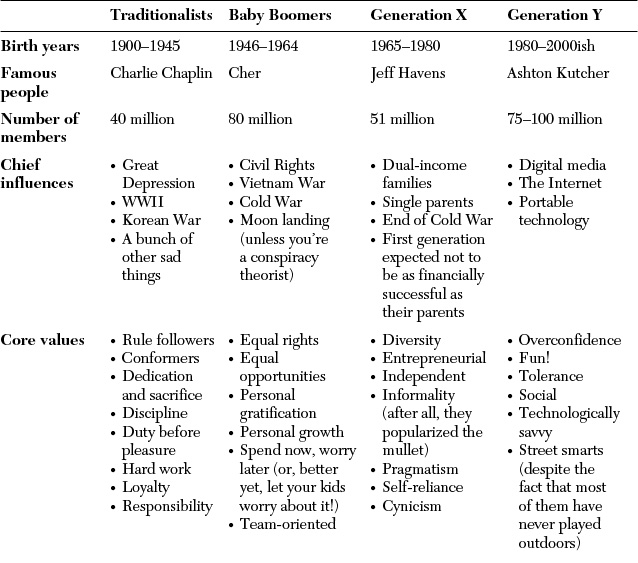

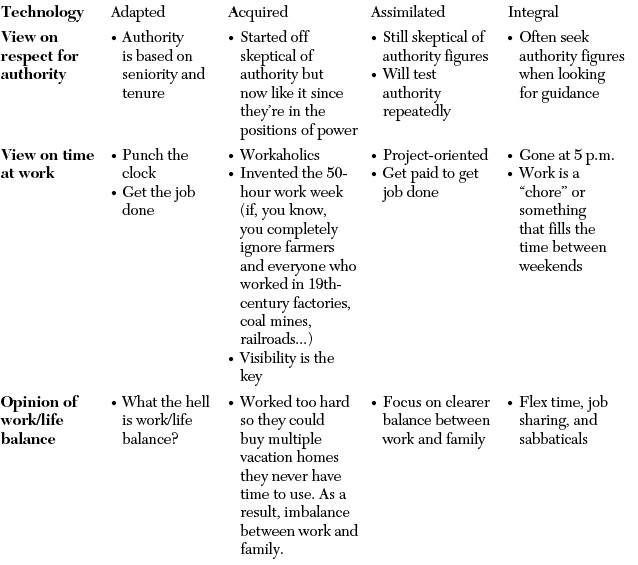

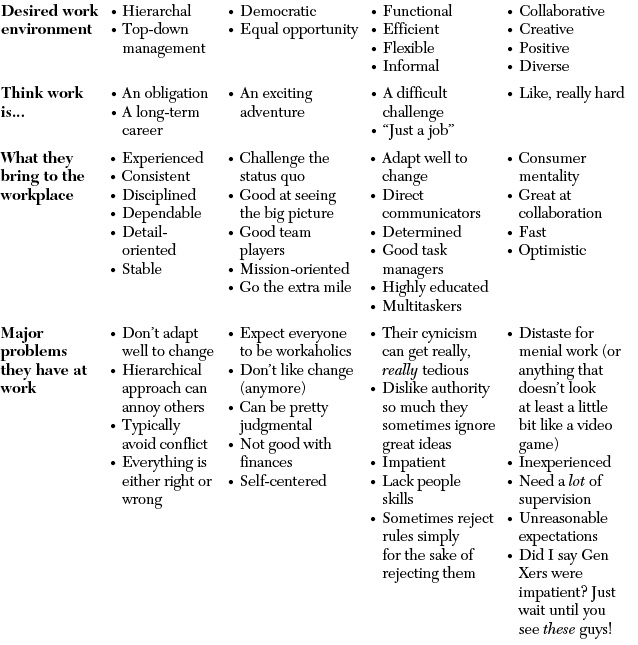

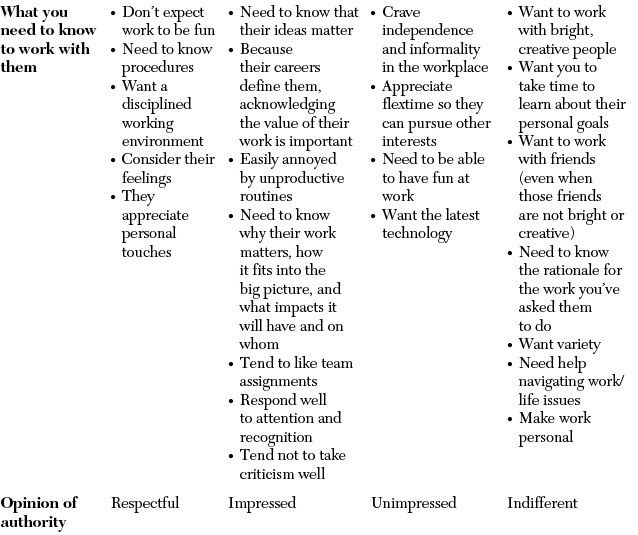

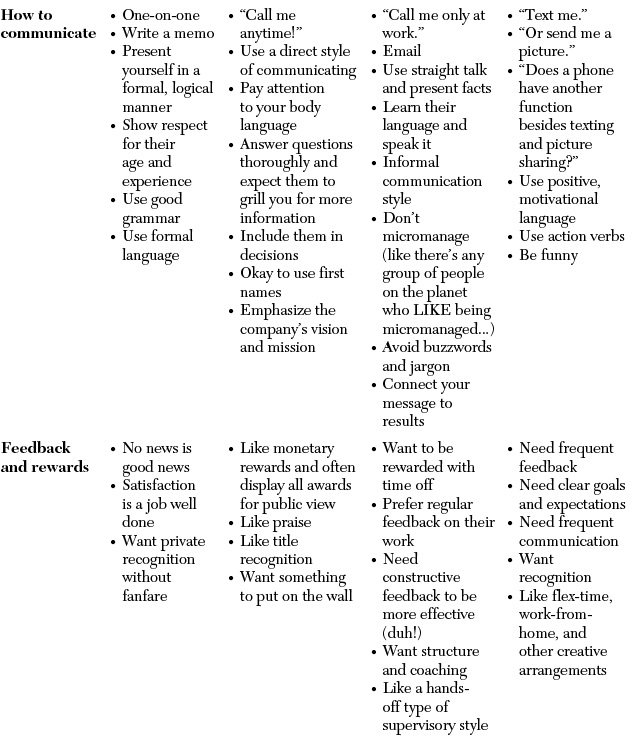

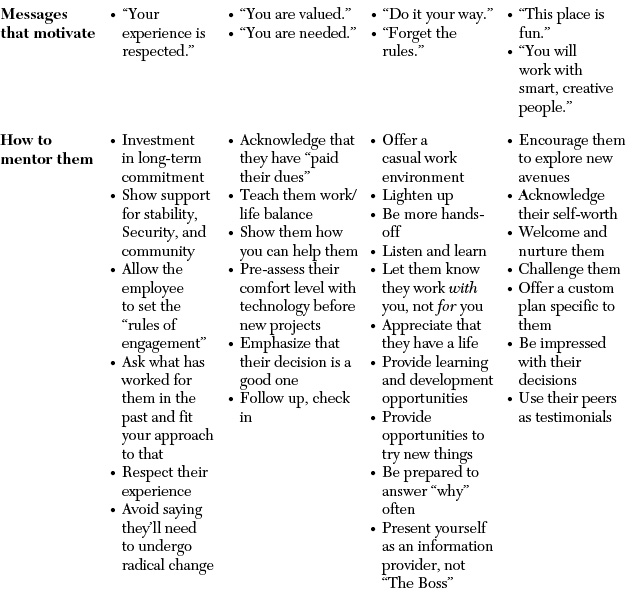

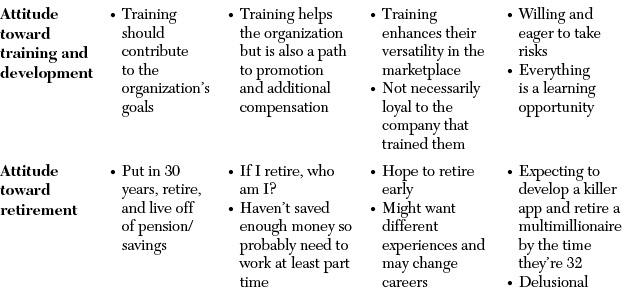

I’m going to give you one of those charts here. Table 1.1 is a compilation of several of the various generational charts I’ve seen. I’m certain you’ve seen something very much like this chart before. And I truly hope you don’t read it; the only reason I’m putting it here is so you can be reminded of how the four-generation model is typically structured. You’ll understand my subsequent arguments whether you read this chart or not. However, if you do choose to read it, I promise I made a few small embellishments that should entertain you.

This is what you’ve heard. This is what you’ve seen. And it is almost completely useless.

Honestly, what manager has the time or even the ability to put a chart like this into practice? Who can afford to sit at a desk, putting everyone she manages or works with into this chart, analyzing their supposedly rigid attitudes about a couple dozen different elements of work, life, and the balance between them—and then devise solutions tailored to each person’s incomprehensibly specific needs and motivations? And even if you could somehow find the time to do such an exhaustive independent analysis, the larger question remains: With so many glaring and seemingly insurmountable differences between the members of so many different generations, who can even hope to find successful managerial techniques, change management strategies, or anything else when it looks as though everyone 15 years older or younger than we are is essentially a completely different type of person?

In the interest of making it easier to describe people based on their age, we’ve made it enormously more difficult to develop real solutions for a diverse workforce.

It’s time for a better way. It’s time to think about generational differences the way we used to before we needlessly complicated the issue and turned simple issues like how to dress for work into grueling, heated arguments between multiple factions. This book is for anyone who has grown tired of our current method of discussing generational differences. It’s for anyone who has sensed that this problem may not be as difficult as we’ve made it out to be. And it’s for anyone who thinks that we might all be a little more alike than we are different.

So say goodbye to the four-generation model because I won’t be referencing it again. I might occasionally use terms like Baby Boomer and Gen Xer while making various points, but I’ll only be doing so as part of the process of reframing our current four-generation model in the terms of the two-generation model we’ll be discussing from here on out. If you think it arrogant or audacious to try to overturn several decades of established theory about generational differences in the workplace and replace all that with a new model, I understand why you might think so.

But to be perfectly honest, the two-generation model you’re going to be reading about is not new at all. Not by a long shot.