5. On The Pace of Career Advancement (In Any Career)

If for any reason you chose to stop reading at this point,1 you would walk away from this book with everything you need to know to create the kind of workplace culture that will inspire loyalty in everyone, Young People and Old People alike.

1 I don’t know why you would want to do this, but possible reasons include “lost will to live” or “unexpectedly became illiterate.”

However, having a loyal workforce in no way guarantees that you’ll have a productive workforce. Loyalty plays an enormous role in determining whether your colleagues and employees are interested in working hard, but it’s not the only factor. When it comes to instilling a killer work ethic in your company, department, or team, a more important question you’ll have to answer is whether your people actually want to be productive in the first place.

If you’ve never complained about a colleague’s subpar work ethic, then you’ve probably spent your entire career working alone. But even then, you were almost certainly assigned to group projects in high school and occasionally whined to your parents that you were doing all the work, while your worthless classmates just screwed around and got the same grade you did.

You’ve probably done the same with a few of your professional peers as well. But a curious thing happens when we feel as though our colleagues aren’t putting in the same effort we are. If those people are roughly our age, we usually resign ourselves to the fact that some people just work harder than others. However, when we’re complaining about a lack of work ethic in people who are significantly Older or Younger than we are, our logic starts to shift.

That logic can best be summarized by the following two stories:

There’s a good chance you’ve felt like Barry or Randall, or possibly both of them. It’s easy to imagine anyone with a few years’ experience echoing Barry’s comments, and it’s easy to imagine an 18-year-old new hire parroting Randall’s frustration. Older or more-experienced people are forever accusing their Younger or less-experienced colleagues of idleness, laziness, and unreasonable expectations, and Young People continually criticize their elders for resting on their laurels and doing as little as necessary to keep their jobs. Ironically, when it comes to this particular element of generational discord, each side is blaming the other for exactly the same thing—not working hard enough.

You’ll also notice that there are only two versions of these stories rather than four. That’s because if you’re a so-called Traditionalist, you don’t have one criticism about the work ethic of Millennials and a different criticism about the work ethic of Gen Xers; as far as you’re concerned, they’re all just young and lazy. And if you’re a Millennial or Gen Xer, you don’t have different problems with your Baby Boomer and Traditionalist colleagues because to you they’re all determined to twiddle their thumbs for the rest of their careers. The two-generation model strikes again!

So what you’re really dealing with is the same issue interpreted from two distinct points of view. However, that does not mean the issue of work ethic is perfectly balanced between lazy Young People on the one hand and burned-out Old People on the other. The issue of stagnant and enervated Older workers is undoubtedly real and one we address later in this chapter. But hardly anyone would argue that the far greater problem is the tsunami of Young People who just flat-out don’t seem interested in working hard. We’ve talked about how the nature of today’s employer–employee relationship has, in many cases, negatively influenced Young People’s attitude toward work in general and toward their employers in particular. But if you’re doing everything you can to give them a place to belong, and if you’re providing them with solid reasons to be loyal to you, why are so many of them still under the delusion that they can show up to work whenever they feel like it? And why do any of them expect to be promoted four months after getting hired?

There are two main reasons that the Young People you’re working with today seem to have such an anemic work ethic. The simplest answer is also one of the easiest things in the world to overlook: The Older colleagues you currently work with are the ones that either demonstrated a healthy work ethic from the beginning or figured out the importance of a strong work ethic very, very quickly. If you could look back at everyone hired into your company in 1950 or 1975 or 1992, you’d almost certainly find a collection of people with varying work ethics, just like you’re finding today. The ones who were willing and eager to work hard have stuck around and been promoted and otherwise advanced in their professions; the ones who weren’t willing or eager to work hard have long since been fired or otherwise been encouraged to seek opportunities elsewhere. So, quite simply, if you’re an Old Person, the reason your same-age peers often seem to possess a uniformly solid work ethic is because the ones who didn’t have a good work ethic aren’t around anymore to skew the numbers.

The second reason, however, takes a little longer to explain. Many of today’s Young People are operating under a false assumption, one they’ve inherited in part because of the technological world they’ve grown up with. If you’re an Old Person trying to figure out how to instill a first-rate work ethic in your Younger or less-experienced colleagues, you’ll soon know what to say to them.

And if you’re a Young Person, I’m about to tell it to you myself.

A Secret About Every Old Person You Work With

This section is written specifically with Young People in mind, but everyone should read it.

Young People, I know that part of the problem you sometimes have with your Older colleagues is that you feel like they’re in your way. Even if you don’t want to admit it, part of you thinks they’re accidentally or maliciously blocking your forward progress. That’s not exactly a fair way to think, but it’s not unreasonable, either. If it’s any consolation, every one of them sometimes felt the same way when they were in your position.

Which leads us to the secret about every Old Person you work with, one you need to fully understand. Brace yourselves...

They weren’t always Old People.

I know how difficult that is for you to believe. After all, they’ve always looked like Old People to you. If there happens to be an Old Person nearby,2 do yourself a favor and stare at them for a bit. Note the crow’s feet around the eyes, the receding or non-existent hairline, the bifocals and walking canes and daily cocktail of medications, the stooped shoulders and jowly cheeks. They’re so old! And for as long as you’ve known them, they’ve always been old.

2 If there isn’t, you can probably find one at a nearby golf course or your local Cadillac dealership.

However, that just isn’t true. They weren’t always Old People; they changed into Old People, slowly and over time. Naturally, you understand this, but it’s surprisingly easy to forget, the same way all of us have forgotten what it really and truly is like to be 5 or 8 or 13 years old.

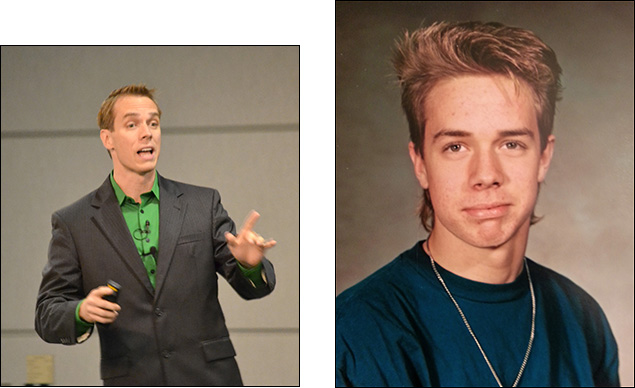

But enough talk. A picture is worth a thousand words, and so the best way to illustrate the fluid nature of the life that your Older or more-experienced colleagues have lived is to allow you to compare what I look like today (left) ...with what I looked like in my 9th-grade yearbook photo (right):

I’ll give you a moment to let these two images sink in.

The one on the left is presentable, right? I’d argue that I look at least modestly competent. I’m reasonably well dressed. Based only on this photo, it’s not entirely inconceivable that a company that chose to hire me might not completely regret the decision to do so.

However, there’s no disputing that my 9th-grade photo is a complete atrocity. It’s impossible to fully enumerate all the bad decisions I had to make simultaneously in order for you to have this photograph to look at. Your eyes will no doubt have first been drawn to my hair, that rakishly lopsided Vanilla Ice pompadour that gives my head the vague anvil shape that was exactly as appealing to women back then as it is today.3 You might forgive the awkward expression on my face as the sadly unavoidable consequence of adolescence. But nothing can forgive that partial mullet I was rocking in the back. Even if you condemn the mullet in all its forms, you should at least concede the confident bravado required to wear one. Alas, I couldn’t quite get there. Instead of a party in the back, mine was more of a quiet get-together. Oh, and that chain I’m wearing? Suspended at the bottom is a dragon claw holding a crystal ball. I couldn’t make that up even if I wanted to, and why on Earth would I want to? I suppose I could argue that I was simply 20 years ahead of my time—after all, Game of Thrones is really popular right now, and it has plenty of dragons—but my anvil-shaped semi-mullet sort of kills that argument before it gets off the ground. As you might have already guessed, my 9th-grade girlfriend was imaginary.

3 I spent about 40 minutes every morning on that hairdo, by the way. Repeat: For well over a year, I spent 40 minutes every morning—consciously, meticulously, and intentionally making myself look this bad.

However, over the past two decades, I’ve slowly and steadily gotten better. In that sense, I am much like a fine cheese.

Experience, Experience, Experience

And just as I have changed over the years, so have all the Old People you work with. This leads to the first point about the nature of career advancement that you absolutely must understand if you hope to have a happy and successful professional life:

None of the Older people you work with got where they are overnight.

This sounds like such an obvious statement that it hardly needs to be said, but it does. If you’re relatively new at your company, then all of your Older colleagues seem to have simply always been there, doing the same jobs today that they’ve been doing forever. But that isn’t true. They’ve spent years working their way into their current positions, if not at your company then somewhere else, slowly building the skill set necessary to do the jobs they’re currently doing. Years. Not days, not weeks, not months—years.

If you’re a typically ambitious Young Person, or if you’re currently less experienced than many of the people you work with and eager to be taken more seriously, then you’re probably fairly confident that you already have everything you need to run things yourself. That supreme belief in our skills and abilities is one of the foundational qualities of youth. I thought it myself when I was younger, as did each and every one of your Older colleagues, although many of them will have forgotten that they used to think that way; indeed, forgetting how we used to think plays a definite role in generational tensions because as we age we become progressively less and less able to empathize with our Younger or less-experienced colleagues.

However, even if it’s somehow true that you are the most capable, competent, and intelligent person at your company, you can’t prove that to anyone without some experience behind you. Career advancement is exclusively a function of experience, not age, although the two often go hand in hand given the process of gaining experience necessarily involves getting older. It’s not always a perfect correlation, however, and there are myriad examples, most notably in the technology sector, where the most-experienced individuals are significantly Younger than the people they employ. This can be a problem for Old People, who sometimes feel that age necessarily confers seniority and that they therefore deserve to occupy the most important positions. With rare exceptions, though, people are in the positions they’re in because of their experience, not their age.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. A moment ago I allowed for the possibility that Young People might actually know everything there is to know about the companies or industries where they work, and that just isn’t true. Not only that, but if you’re a Young Person, you also don’t know as much as the people who’ve been there a decade longer than you have.

You don’t have to take my word for it, though.

The 10,000-Hour Rule (Which Is a Lie but Gets the Point Across Anyway)

In his book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell popularized the notion that 10,000 hours is the amount of time it takes to become an expert in something. For those of you who haven’t read it, he based his hypothesis on the work of psychologist K. Anders Ericsson, who, along with two colleagues,4 studied violin students at Berlin’s Academy of Music. The students were divided into three groups: those who had been judged by their teachers to have world-class potential, those considered good enough to play professionally but not at an elite level, and those considered incapable of achieving professional-level success.

4 Who are probably annoyed that nobody knows their names, by the way.

Here’s what they found:

Students who would end up as the best in their class began to practice more than everyone else: six hours a week by age nine, eight by age 12, 16 a week by age 14, and up and up, until by the age of 20 they were practicing well over 30 hours a week. By the age of 20, the elite performers had all totaled 10,000 hours of practice over the course of their lives. The (second tier) students had totaled, by contrast, 8,000 hours, and the (third tier) just over 4,000 hours.

As you can see, Ericsson and colleagues found a direct correlation between practice and proficiency—in other words, practice really does seem to make perfect. Based on these findings, Gladwell argued that 10,000 hours is the magic number of time required to become an expert at anything, and now we all repeat it as though it’s a definitive answer. In fact, if you Google “How long does it take to become an expert?” the first thing that pops up is a giant 10,000 hours, as though that’s all there is to it. According to Gladwell, five years of full-time dedication to a given skill will make anyone an expert.

So you should be running your company after five years, right?

Unfortunately, this conveniently simple solution suffers from a few problems. First, the 10,000-hour answer completely ignores the effect of natural talent. The students in Ericsson’s study, for example, had been presorted by their music teachers in terms of natural ability. The “expert” group had already been identified as having the potential to become experts, while the third group had already been identified as lacking that potential. Although it’s certainly possible that practice and determination might permit anyone to become a world-class violinist, it’s also true that those people might have to practice more than 10,000 hours to do so—or that musical prodigies might have to practice less. It also doesn’t take into account any physical or genetic factors that might play a part in determining expertise. I could spend all the time in world perfecting my basketball skills, but I’m 5’11", and it’s difficult to imagine any level of commitment on my part that would overcome the fact that most NBA players could block my shots without having to jump.

Second, Gladwell’s insistence that 10,000 hours is invariably the threshold of expertise also overlooks the fact that some skills are more complicated to master than others. Becoming a world-class neurosurgeon, for example, is just plain harder to do than becoming a champion poker player. In fact, others have actually gone to the trouble of attempting to calculate the amount of time necessary to achieve expertise in a variety of fields, and the answers vary considerably—7,680 hours for poker players, 13,440 for chefs, 700 for yoga, 9,600 for sports, 15,360 for computer programming, and 42,240 for neurosurgery. Thus, the skill you’re attempting to master has a significant effect on how long you’ll need to spend on it to master it.

Third, the idea of achieving expertise simply by powering through 10,000 hours of practice doesn’t take into consideration the quality of that practice. Without the proper coaching or studied reflection, practice doesn’t lead to improvement. You might advance to a certain point simply by doing the same thing over and over again, but you’re unlikely to become an expert unless you’re analyzing your progress, experimenting with new approaches, and studying the success of recognized experts in your field. That’s the reason professional athletes have coaches, and it’s the reason that having a mentor is critical if you want to reach the upper echelons of any business.

So Gladwell’s 10,000-hour rule is hardly perfect. Some people might advance more quickly than you because they have greater natural aptitude than you do, because they chose an easier path than you did, or because they have devoted more time to analyzing their progress than you have. Because all three of these factors are working simultaneously but to different degrees within each of us, it’s fairly difficult to state conclusively that my five years’ experience should be more highly valued than your four years’ experience.

However, the idea is sound—that is, we get good at things because we spend time working on them. As long as we put in the time to learn from our failures, analyze our successes, and push to become better, then all of us have an inevitable tendency to actually get better. In the broader sense that concentrated practice is the key to advancement, Gladwell and Ericsson’s 10,000-hour rule is as useful a number as Dunbar’s 150 is for the number of people you can actively care about at any given time. You might be able to master your craft in 8,000 hours if you’re naturally gifted at it, you might need only 5,000 if it’s a fairly easy skill to master, and you might take 14,000 if you’ve chosen something more difficult or don’t have the right coaches to help you along. But no matter what your particular circumstances, you should expect to devote a lot of time to getting good at whatever you want to get good at, whether it’s perfecting your slap shot or earning accolades in your career.

And you know what that means for you, Young People?

Advancement Is a Process

Yes, Young People, advancement is a process. This is probably the most important thing to understand if you want to resolve any generational tensions related to career advancement, and it is an essential concept to understand and internalize if you want to have a happy and successful career. Advancement is a process, not a right. We do not get promotions or awards or raises the way that we get presents. We earn promotions and awards and raises. We earn them as a result of our experience, and the only way to accumulate that experience is slowly and methodically, the way that all your Older or more-experienced colleagues have done.

Unfortunately, “slowly and methodically” is not a speed Young People generally enjoy. Not only do Young People typically prefer things to move more quickly than Old People, but the notion of slow and steady progress runs counter to the rapid-fire pace of the modern world. We talk more about that in a few pages, but for now, it needs to be said that your career advancement won’t be slow because your Older or more-experienced colleagues are insisting on it.

Rather, advancement is a slow process because that’s its nature—not just with your career, but with everything that we do.

Your answers to the following two questions should help you convince yourself.

Quiz: Show Me The Money!!!

1. How do most professional athletes become professional athletes?

A. They ask really nicely.

B. Their parents gave them cool first names like Plaxico and D’Brickashaw, thus guaranteeing their eventual stardom.

C. They train constantly, endure injuries, analyze countless hours of game film, eat a depressingly tiny amount of french fries, travel continuously, and I could go on.

D. They’re really good at all the Madden games.

2. How do most professional musicians become professional musicians?

A. They practice, write, record, and tour constantly—like the Beatles, who played at least 1,200 shows in Germany between 1960 and 1964, the majority of which were attended by people who probably didn’t know who The Beatles were.

B. They live near a record shop.

C. They experiment with heroin.

D. They watch a lot of music videos on VH1 and YouTube.

The answers are obvious—and this is how advancement happens in everything we do. Some people have a natural gift for athletics, others for music, others for sales, and others for management. Some people work harder than others. Some people have better access to educational resources than others. Some few people are even luckier than others. And perhaps you’ve been privileged enough to have all of these factors working in your favor. Perhaps you’re the smartest, hardest-working, luckiest, and most innately talented member of your entire company. But even if that’s true, you still can’t expect to advance without dedicating countless hours of time to honing and perfecting all of those natural gifts. In the history of professional football, nobody has ever picked up a football for the first time and immediately started playing in the NFL. In the history of music, nobody has ever picked up an instrument and immediately played complete songs to an enthralled audience at a packed amphitheater. And in the history of business, nobody has ever been an overnight success, despite what you read online.

The point is, you have to practice everything in order to get good at it. That’s why we tend not to marry people immediately after going on a great first date, although you can definitely do it in Vegas if you want to. But you shouldn’t, and your friends will make fun of your poor decision making if you do. The development of a healthy relationship takes time, and there’s no shortcut for that. You have to practice video games before you can beat online opponents, languages before you become fluent, recipes before you can perfect them, home improvement projects before you can finish them as well as a contractor might have, and even parenting before you start to feel like you really know what you’re doing. Everything we do requires time, dedication, and practice. It’s as simple as that.

Young People, when it comes to your career, you simply must realize that a career is not a separate kind of experience from the other experiences in a person’s life. A career is simply another experience—an experience that requires the same things as all the other experiences we ever have. We start, we learn, we improve, we screw up a few times, we learn from our mistakes—and if we’re smart and focused and don’t quit, and then we continually move forward.

Again, advancement is a process. And when it comes to your Older or more-experienced colleagues, the simple fact is that they’ve been going through that process longer than you have. There will always be a few incompetent people in positions of authority who owe their success more to luck or family connections than anything else, but those cases are the exception rather than the rule. In the overwhelming majority of cases, your Older or more-experienced colleagues are where they are because they’ve worked extremely hard to get there.

Karen’s specific experience might be unique to her, but the long and unpredictable path her career has taken absolutely isn’t.

This isn’t to say that your Older colleagues always have the best ideas or that their greater experience is always the best guide for determining how to address new business practices or disruptive technologies; we discuss those issues in more detail in the next chapter. Right now, though, what’s important to understand is that all the people you work with who have been with your company longer than you have earned their way into the positions they’re in today. They’ve done it through a combination of hard work, study, perseverance, trial and error, collaboration with their peers, stubborn refusal to quit, and the occasional injection of dumb luck. They’ve powered through some difficult times, and in some cases they’ve encountered and overcome existential threats to your company’s survival. They might not often talk about those moments because the people who do can be just as annoying as that friend of yours who won’t shut up about his glory days playing high school football. But they’ve worked hard to get where they are, and they deserve respect for that.

And Now, Something for Old People

We’ve now explained to Young People why their Older or more-experienced colleagues are where they are, how they got there, and how they themselves will get there in the future. If you are Young or relatively inexperienced compared to your colleagues, this should help you see Old People in a different and healthier light. With respect to career advancement, the business world is operating just as it always has. Unlike with our evolving pension and healthcare systems, Old People are not taking advantage of benefits that today’s Young People don’t have access to. The path to career advancement is a process, the same as it’s always been, and Old People have typically been going through that process longer than Young People. Hopefully this realization will help reinforce the notion that when it comes to career advancement, all of us are far more Us than Them.

However, if you’re generally Older or more experienced than your colleagues, then you’ve probably been reading the last few pages with a fair amount of incredulity. “Advancement is a process? You have to put in some time before your efforts are going to be rewarded? Of course!!! Who in the world doesn’t already know this?” If you’ve experienced any amount of generational tension with your Younger or less-experienced colleagues, a lot of it probably has had to do with your frustration that you even have to talk about this issue in the first place.

So we’re now going to discuss two concepts that will mitigate this frustration. The first will explain why the concepts of hard work and delayed gratification seem to have become more difficult for today’s Young People to grasp than they may have been for you, and the second will remind you that it’s not only Young People who suffer from an occasional aversion to hard work.

But first things first: Why do we even need to talk about the nature of career advancement and the importance of hard work? Isn’t this stuff so obvious that we shouldn’t need to have a conversation about it? The answer should be yes, but it isn’t. To understand the reason for that, we’re turning once again to our recent technological revolution in general and the Internet in particular, both of which have given many Young People a misconception about the nature of advancement.

The One Thing Technology Can’t Improve

I’m certain that while I write this paragraph, I’m going to screw something up. There will be a word I don’t like, or a phrase, or maybe I’ll realize halfway through that I’m just not saying things the way I want to. So I’ll mash my pinky finger on the Backspace key and start over like nothing happened. Fifty years ago, I would have had to rip an entire page out of my typewriter and begin from the top. Five hundred years ago, I would have just ruined a piece of parchment worth more than some houses. And five thousand years ago, I would have defaced an entire cave wall—which I could probably have erased by chiseling out the entire offending section, but man does that sound tedious.

There is absolutely no question that technology has improved our lives in almost every imaginable way. We can eat foods our ancestors didn’t know existed, and we can grow that food with a confident certainty they never experienced. We can travel distances that not too long ago were literally inconceivable. We can encode information on light beams, which I am doing right now and which is still so bewildering to me that I sometimes think it’s all just magic. Our technology is so ubiquitous and has been demonstrated to improve so many areas of our daily lives that it’s tempting to believe it can do everything. Need to cure a disease? Engineer a drug. Want to meet the love of your life? Use a computer algorithm that matches people according to their preferences. Interested in living a few hundred years? There are people working on that. Whether they’re successful or not remains to be seen, but the very fact that some people think it’s even possible suggests that there’s no limit to what technology can accomplish.

But there is. Because despite its myriad miracles, technology simply does not and cannot improve the rate at which we acquire knowledge or develop skills. There is no machine that can turn you into a doctor in six months; there is no software program that can shortcut your path from piano owner to concert performer. Nothing we have developed, and nothing we are going to develop in the foreseeable future, can accelerate the process by which you learn an instrument or master a language, excel at a sport, or become a world-class parent. Start, practice, fail, learn, practice, fail, learn, repeat—for the entirety of human history, that is the only solution we’ve ever come up with. If a given skill required 1,000 hours of study in the past, that same skill requires 1,000 hours of study today. Some people learn more quickly than others, some people practice more than others, and some people have a greater natural aptitude for a certain skill than others. But technology simply can’t do anything to help.

Our technology has made access to knowledge infinitely easier than it was in the past. The Internet has placed the entire wealth of human knowledge at our fingertips. When I was younger, I had to go to the library to find information, and then only after wading through the swampy morass of the Dewey decimal system could I hope to find a book that might maybe be useful. Now everything—literally everything—is only a click away. With all the video tutorials, courses, lecture series, and other educational offerings available online, a dedicated student might be able to acquire that 1,000 hours of knowledge significantly faster today than was possible to do in the past. But there’s no getting around the fact that you’ll still need to devote those 1,000 hours to learning, trying, failing, and learning some more. That is the only system for acquiring knowledge that we have ever developed.

We have a tendency to forget this. Technology has sped up so many other things that we sometimes rage at how long it takes to earn a work promotion or become an expert. A lot of us expect those things to simply happen, as though you can scroll through a few screens on your smartphone and suddenly have the knowledge it’s taken your more-experienced colleagues a decade or two to acquire. Young People are more prone to this impatience because they were literally born in a world where everything has always been moving at the speed of light. But let’s face it, every one of us has given up on something 15 minutes after starting because we weren’t already good at it.

However, if you want to achieve success at any element of life, personal or professional, the immutable and glacial pace of advancement is a fact you absolutely must come to terms with. Nothing you are good at today came quickly or easily, and nothing you want to become good at will happen overnight. If you expect online dating to pair you up with the perfect match without suffering through any bad dates, you will almost certainly be disappointed. If you expect promotions at work every few months, you will have an extremely difficult time being happy at any job you ever hold. If you expect to lose 30 pounds in a month without having to exercise or change your diet or otherwise do anything disruptive, you will very likely never see the results you want. I’m currently two years into learning Spanish, and I still can’t understand half of what native Spanish speakers say when they talk at their normal machine-gun rate.

Getting good at something is always a marathon; it always has been, and it always will be. If you aren’t prepared to run that race, then you shouldn’t expect to get any better at anything than you already are. We have done some truly awe-inspiring things, and our great-great-great-grandchildren will come up with technologies we can’t even imagine. But none of that can put skills and knowledge into your head any faster than our caveman ancestors were able to do it themselves. The Matrix lied to us.

And that’s why I hate Keanu Reeves.

How This Causes Tension

As mentioned in Chapter 4, some of the generational tensions you’re experiencing at work are results of the technological revolution that separated us into two groups: people who developed their sense of self before computers and the Internet became an integral part of our daily lives and those who came after. With respect to the different attitudes Young People and Old People have about career advancement, the same forces are in effect. Today’s Young People have been operating in a world where almost everything happens faster now than it used to. As a result, many of them have made an unfortunate but relatively honest mistake in thinking that their careers will advance more quickly than careers did in the past. After all, if everything else is moving faster now than it did before, why not this, too? Again, it’s an unfortunate assumption that some of them have made, and it does fly directly in the face of all their other experiences—learning a sport, an instrument, a language, and so on—but there is at least a certain logic to it.

Moreover, and as we also briefly referenced in Chapter 4, many Young People have grown up watching so many stories of “overnight successes” that some of them have started to wonder why the same thing isn’t happening for them. They’ve seen LeBron James making millions of dollars playing in the NBA before his 20th birthday; they’ve seen Mark Zuckerberg found a billion-dollar company in his 20s; they’ve seen Theo Epstein become the youngest manager of a professional baseball team at the age of 28; and every week there are hundreds or thousands of similar examples to suggest that success shouldn’t be terribly difficult. Unfortunately for these Young People, what those stories almost never mention are the tens of thousands of hours of practice that James, Zuckerberg, Epstein, and all the others put into their respective careers, most of it in obscurity, until their single-minded dedication finally paid off.

Also, it would be an inexcusable omission on my part if I didn’t mention that many of today’s Young People have been raised in a world that has actively fostered their belief that success is easy. From scoreless soccer leagues to competitions in which all participants get a trophy to parents negotiating with teachers who give them failing grades or attempt to discipline them when they’re unruly in class, we’ve constructed a society in which many Young People have been trained to think they don’t have to work very hard to get whatever they want. Many colleges now offer luxury student housing (granite countertops, rooftop pools, free tanning, free housekeeping, etc.) that is beyond the means of many working professionals and that is all but guaranteed to disappoint students who graduate from those universities and then find that they can’t live as well as an adult as they could live in school.

Plenty of books have been written about the so-called Trophy Generation, and virtually all of those books shower contempt on its entitled and misguided members. But before you do the same, try to remember who taught them what they know. Every Millennial you work with today was raised either by Baby Boomer parents or the oldest of the Gen Xers, which means that if Young People really do have a flawed understanding of the value of hard work, it’s we Old People who bear some of the responsibility for the failure to teach it to them.

Advancement Never Stops

I’ve now explained why some of the Young People you work with think about their careers the way they do. If you’re Older or more experienced than your colleagues, this should do something to bring them closer to the Us side of the line. However, the gap between Young People and Old People might still seem significant: Today’s Young People are operating under the influence of different cultural and technological influences than Old People. If today’s two generations are really going to find a common understanding with one another, it would be helpful if we could find some way in which both Young People and Old People behave in exactly the same way.

Fortunately for us, that’s not hard to do. Because in precisely the same manner that many Young People have expressed a disinterest in putting in the time and effort to advance in their careers, plenty of Old People have expressed an identical disinterest. These people have decided that they’ve already learned everything they need to learn and are perfectly happy to coast as long as they can get away with it. If you don’t have some Older or more-experienced colleagues who come in a few minutes late every day, leave as early as possible, consistently shoot down new ideas, and put up a fight whenever they’re forced to engage in any kind of continuing education, then you almost certainly have friends in other companies or industries who have faced this problem.

It’s also all but certain that if you are an Old Person, you’ve agreed with the vast majority of the advice for the Young People reading this. The revelation that advancement is a process surely seemed obvious to you, which we’ve mentioned a few times already. And this means it should be equally obvious that advancement is a process that never stops.

If any of your Older or more-experienced colleagues are suffering from a faulty work ethic, it’s probably not that they never had one to begin with. Very few people manage to move into positions of authority, or even to survive for decades in the same position, without having worked hard to get (and stay) there. Instead, some of your Older colleagues have simply forgotten that we can never stop learning and pushing and trying new things, no matter how experienced we think we are.

This is true for both our personal and professional lives. When we addressed work ethic for Young People, we demonstrated that the process by which we improve at our careers is the same process by which we improve at sports or instruments. The same is still true whether you have 2 years’ experience or 20. Concert cellists are constantly practicing in order to get even better than they already are, and 40-year-old athletes continue to train in order to stay at the top of their game. The ones who choose not to are the ones who eventually get eclipsed by their hungrier and more dedicated competitors, regardless of how old those competitors are.

Susan’s story paints a vivid picture. But perhaps the best example of the true nature of advancement is the marriage example we used earlier. It would be ridiculous to propose to someone on a first date because developing healthy relationships requires a lot of time—hence, advancement is a process. However, it would be equally ridiculous to suddenly stop telling your spouse of 17 years how much you love him or her because healthy relationships require constant maintenance in order to be sustained—hence, advancement never stops.

Hopefully you see the point. Our careers require a continual effort on our part, in much the same way that our personal relationships do if we want them to be happy and successful. If you’re a parent, then you’ve certainly had moments when you’ve felt like the workload was simply too much to bear—every moment a new crisis, every day another bloody nose or homework assignment or baseball practice to coach. But somehow you’ve found the strength to continue. Our careers require the same dogged persistence.

In many cases, those Old People who have stopped progressing in their careers have done so for two main reasons. The first, which is the simplest to explain and understand, is that they’ve found they can get away with it, and all of us are occasionally susceptible to doing what seems easiest. The second reason is that they believe the experience they’ve already accumulated should be sufficient proof of their talent and ability, and that has encouraged them toward complacency. We discuss this phenomenon in greater detail in Chapter 6, along with various ways to deal with it.

For now, what’s important is that here we have a single arena in which Young People and Old People behave identically. Advancement is a process, and that process never stops. All of us have been living our entire lives according to this inevitable reality, and all of us sometimes forget the truth of it. That we sometimes forget is an issue we can work with. That we’re all following the same blueprint means, once again, that we’re all much more Us than Them.

The following two biographies should drive the point home. If you’re struggling to instill in your Younger or less-experienced colleagues an appreciation for a robust work ethic, either of these should help you illustrate how long it sometimes takes to achieve success. If instead you’re trying to convince an Older or more-experienced colleague why they shouldn’t succumb to the temptation to relax, either story should reinforce the incontrovertible truth that the time to throw in the towel is exactly never.

What You Can Do

As with our discussion about loyalty in Chapter 4, resolving generational differences with respect to work ethic and career advancement is much easier than it might seem. As before, the first step is to determine what Young People and Old People have in common.

That’s really all there is to it. Young People have a tendency to forget that advancement is a process, while Old People have a tendency to forget that the process never stops—but everyone is operating within the same system. As with our discussion of loyalty in the previous chapter, all of us are much more strongly Us than Them when it comes to career advancement.

Also because our careers function the way that all other experiences do, it is easy to use the example of common experiences to illustrate why slow progress and a solid work ethic are essential for career advancement at every stage of a person’s career. One of the most effective ways to convince anyone of anything is to use examples that relate directly to their own lives, and we discuss this in more detail shortly, when we talk about strategies.

Now for step two—explaining why the people from each generation think and behave the way they do. Obviously, we’ve just spent most of the chapter looking at this in detail, but the following summaries should convince you that these differences are actually quite small and, more importantly, eminently manageable.

Again, you’ll notice significant similarities here. Some Young People are naturally lazy, and some Old People have become lazy. Anyone who has a certain amount of experience, whether a Young Person or an Old Person, expects to be respected for that experience.

So if you are a Young Person and want to have a decent working relationship with your Older or more-experienced colleagues, make sure they know that you respect their experience. You can accomplish this in a number of ways but probably most easily by simply consulting them to learn from them the strategies they have traditionally found to be successful. And if your Older colleagues seem to be constantly demanding that you work harder than you currently are, try to recognize that insistence for what it is—that they’ve been around long enough to see the rewards of their own hard work, and they want the same for you.

Whether you like it or not, Young People, your Older or more-experienced colleagues are the gatekeepers for your company. It’s a position they worked their way into, just as you will someday work your way into it, and it’s a position that comes with an enormous amount of influence. They know how to get things done. They know who you need to talk to. They know which rules you need to follow religiously and which ones you can afford to bend a little bit. You need to treat your Older colleagues like the assets they are instead of looking at them as obstacles you have to figure out how to avoid or overcome. Remember from our conversation about loyalty, it is primarily the responsibility of the Older or more-experienced generation to begin the conversation and create the right conditions for developing a culture in which loyalty can thrive. Here, however, it’s Young People who need to begin the conversation. Your Older or more-experienced colleagues have earned it.

However, if you’re Older or more experienced than the people you’re trying to work with, you aren’t totally off the hook here. It’s your job to recognize that respect when it’s given and respond by helping your Younger or less-experienced colleagues along the path to their own career advancement. Several people—coaches, colleagues, great managers, and others—have helped you reach the level you’re at today, and really the only way that a business survives past its founders is for its more-experienced employees to coach and train the less-experienced ones. That is the essence of succession planning.

Also, remember the Sun Microsystems mentorship study from the previous chapter? Choosing to mentor one of your promising Younger colleagues will end up being as beneficial for your own career as it will be for the person you mentor. So you can reach out to your promising younger colleagues because it’s the right thing to do for them and for your business, or you can do it because it will help you personally. You win either way.

Also, it’s important to point out that work ethic and loyalty are related qualities. If you’re struggling with a Young or inexperienced employee who doesn’t seem to have the kind of work ethic you expect—or even an Older colleague who seems to have lost interest in working as hard as before—make sure you’re doing everything you can to create the right environment to encourage their best efforts. Try also to remember that while there may not be anything you can do to correct years of bad training, you can easily address any unreasonable expectations your colleagues of all ages might have about the speed at which their careers will advance.

But enough philosophizing. Let’s get to the strategies. As before, regardless of which side of the generational divide you find yourself on, the things you need to do here won’t cost you a dime.

Fundamentally, the generational issue over career advancement boils down to a simple fact that we’ve already mentioned but that bears repeating: All of us, regardless of our age and experience, occasionally forget something we’re supposed to remember. Young People often forget that getting older is the only way that we are able to gain experience and advance, and Old People often forget that our careers are rarely static, just as our personal lives aren’t. You’ll notice that these strategies are largely a combination of providing reminders, examples, or new perspectives. These are all fairly simple concepts to understand. As we’ve pointed out over and over again, resolving your generational issues in the workplace isn’t complicated.

Nowhere will that simplicity be more obvious than in the next chapter. One of the most consistent complaints Young People have about their Older or more-experienced colleagues is that they only want to do things the way they’ve always done them. There’s an absurdly easy explanation for why Old People think the way they do, and we examine it shortly. We’ll also talk about why that isn’t always a failsafe strategy for success. But mostly we explain why Old People aren’t quite as stubborn and terrified as they’re often made out to be.

So what are you waiting for? You’re almost done with this book, which means you’re almost done figuring out how to resolve every generational issue you will ever face in the workplace. I know you’d rather be jet skiing or whittling or whatever it is you like to do in your spare time, but don’t you think solving all your problems is worth a little delayed gratification? (See what I did there? Hurray for callbacks!) So turn the page already!