4. On the Nature of Loyalty and Its Effect on Work Ethic

By now you’ve seen a lot of statistics that all say the same thing: Workplace loyalty is dead or dying. A 2011 Careerbuilder.com study found that 76% of full-time workers would leave their current workplace immediately if the right opportunity presented itself. A 2012 MetLife survey of employee benefits, trends, and attitudes revealed that workplace loyalty is at a seven-year low, with one out of every three employees saying they plan to leave their jobs by the end of the year. And a 2012 Ernst & Young survey found 69% of respondents believe that employees will be even less loyal to their organizations in five years than they are today. There are plenty more, but let’s stop because I’m starting to depress myself.

The loss of workplace loyalty is typically attributed to the massive influx of Young workers, whose capricious job-hopping is a reflection of their general indecisiveness and specific disinterest in working as hard as their older colleagues. That opinion is so firmly ingrained in Older workers, in fact, that a 2014 survey of 6,000 Young workers and HR professionals found that while over 80% of Young workers (ages 18–26) believed themselves to be loyal to their employers, only 1% of human resource professionals believed the same about the Young workers they employed.1

1 As further proof that loyalty and work ethic are inextricably linked, the same survey found that while 86% of Young workers think themselves to be hard working, only 11% of their Older colleagues thought the same.

Obviously, the disconnect between Young People and Old People on the subject of loyalty and work ethic is a significant one. It’s almost certainly a disconnect you’ve faced yourself. But as you’re about to see, the notion that today’s Young People aren’t as loyal as they used to be isn’t quite as true as most people think. More importantly, you’re also about to find out that whenever workplace loyalty is absent, there are often some very good reasons to explain its absence.

The Importance of Loyalty

The expectation of loyalty is a fundamental quality of every kind of human relationship. If you have children, you expect them to listen to your ideas and advice more than they do to those of other adults. If you have a spouse, you expect him or her to be faithful. If you have friends, you expect them to invite you over and occasionally help you move for nothing more than a few pieces of pizza. If you have employees, you expect them to follow your rules and serve as advocates to potential customers for whatever products and services you offer. In all of these cases, you expect these people to treat you with a certain level of respect.

In fact, loyalty may be the defining element of what actually constitutes a functional relationship. Consider all of the healthy relationships you have with everyone you know—spouse, parents, children, friends, colleagues, bosses, employees, community members, and anyone else you interact with on a regular basis. You probably don’t love all of those people, nor do you benefit financially from all of them. However, in every significant relationship you have, loyalty is a foundational component. To greater or lesser degrees, you expect all these people to listen when you speak, to value your contributions, and to support you when support is necessary. Therefore, when loyalty is present, a healthy relationship is possible. When loyalty is not present, a healthy relationship cannot exist.

Philosophical discussions aside, there is absolutely no disputing the value a company enjoys by having a loyal workforce. It’s almost axiomatic that loyal workforces are more productive, experience less turnover, and produce more innovation than their disloyal counterparts. Here we can see the strong connection between loyalty and work ethic, a connection that is reinforced in the HR study mentioned earlier. Loyal people work harder—it’s as simple as that. Or, to put it into other terms, loyalty brings everyone closer to Us, and the lack of it makes everyone just as strongly Them.

But how are you supposed to foster loyalty when today’s Young People flat-out refuse to be loyal to anything but themselves? And why are they so stubbornly disloyal in the first place? Can an entire generation of people truly be that lazy and self-absorbed?

Could be. Anything’s possible. To figure it out, let’s take a closer look at the loyalty of today’s Young People.

Are Today’s Younger Workers Really Less Loyal Than Previous Generations?

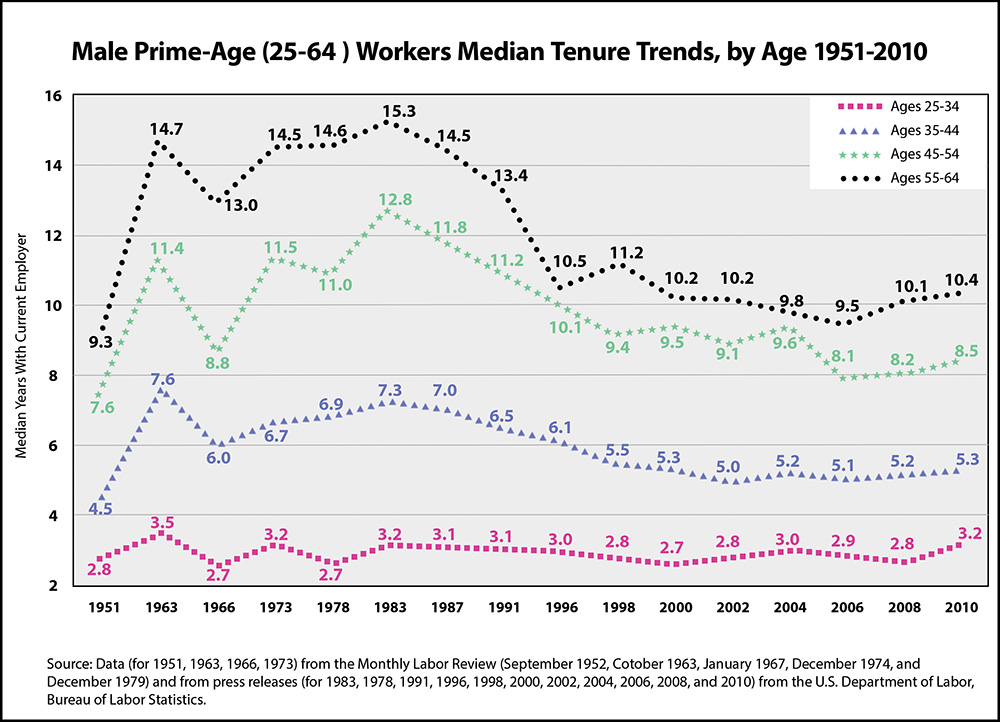

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average tenure of workers aged 55–64 in 2010 was 10.3 years. That’s more than three times greater than the 3.2-year average tenure of workers aged 25–34 years. Moreover, a 2013 Labor Department survey found that today’s Young People have worked an average of 6.3 jobs between the ages of 18 and 25. These statistics have often been used to criticize Young People for lacking both a healthy work ethic and any sense of loyalty to their employers.

So case closed, right? Today’s Young People simply aren’t loyal to anyone but themselves.

Wrong. These numbers don’t come anywhere close to telling the whole story.

First off, it makes absolutely no sense to compare the average tenure of today’s 25- to 34-year-olds with today’s 55- to 64-year-olds because our average tenure tends to increase as we get older. Most of us spend the beginning of our professional lives experimenting with a few different jobs—or falling victim to the occasional wave of “last hired, first fired”—before finding a promising opportunity and settling into a stable career. In fact, it’s impossible for a 25-year-old to have worked with the same company for 10.3 years since (news flash coming): They would have needed to start working at 15, and most of the jobs we’re able to do at 15 aren’t the same jobs we’d like to be doing when we’re 47. I was detassling corn when I was 15, and nobody wants to be doing that job for 10.3 years.

Instead, it makes far more sense for us to compare various age groups with their same-age peers from different time periods. If today’s Young People are indeed less loyal than they used to be, then we should expect to see a historical decrease in the average tenure of 25- to 34-year-olds. The Monthly Labor Review and Bureau of Labor Statistics have done us the favor of keeping track of these numbers for four age groups (25–34, 35–44, 45–54, and 55–64) since 1951. Figure 4.1 shows what they’ve found for men, and Figure 4.2 shows the graph for women.

As you can see, our earlier hypothesis is correct: The older we get, the more loyal we become. This has been true for men and women in every age group, without exception, for the past 65 years.

You’ll also notice a significant spike in average tenure for men and women in all age groups in two places: between 1951 to 1963 and between 1978 to 1983. The first reconciles nicely with our collective memory of the 1950s being a paradise of workplace loyalty and a return to normalcy after the chaos of World War II, a nostalgic view that actually seems to be validated here. The other can be easily explained by remembering what happened during that time—specifically, the recession of 1980–1982, which saw interest rates above 21%. Apparently recessions cause people of all ages to stay at their jobs longer than they might have before, perhaps because of a lack of acceptable alternatives. The same thing seems to be happening today, as you’ll notice an increase in average tenure for all age groups and both sexes from 2006 to 2010, which coincides nicely with the recent recession of 2007 to 2009.2

2 Also, all male age groups and all but the oldest group of female workers experienced a spike in average tenure between 1966 and 1973, during which time the Arab oil embargo caused a serious recession.

These charts show that loyalty tends to increase with age and that recessions tends to result in an increase in worker loyalty (although maybe not for the reasons most employers would prefer). Now let’s address the supposed disloyalty of today’s Young workers.

Let’s start with the men. Look at the tenure line for 25- to 34-year-olds over the past 65 years. It’s virtually flat—far more so than the lines for any of the older three age groups. In fact, far from being less loyal than they were in the past, today’s Young male workers have been at their jobs for exactly as long as their same-age peers in 1973 and in 1983. In the past 40 years, there’s been virtually no change in the amount of time young male workers spend at their jobs. In other words, today’s Young workers are not less loyal than they used to be.

But let’s take this one step farther. Starting in 1983, where average tenure is at or near an all-time high for all four age groups, you’ll notice a precipitous decline in the subsequent 30 years for every age group except the youngest. To be more specific, 35- to 44-year-old men are 27% less loyal than they were in 1983; 45- to 54-year-olds are 34% less loyal; and 55- to 64-year-olds are 32% less loyal. You can argue that outsourcing, layoffs, early retirement, and corporate restructuring have all played parts—and we discuss those arguments shortly—but the fact remains that workers between the ages of 35 and 64 are staying at their companies for less time than they used to, while the rates for the youngest workers have remained constant.

The results for women are quite different. Across all age ranges, their average tenure has climbed steadily, and with few interruptions, for the past 60 years. Naturally, this is a result of women entering the workforce in greater numbers and into more professions over the past several decades. In their case, Older female workers haven’t experienced the same drop in tenure since 1983 as their male counterparts. We discuss reasons for the difference between the trends in male and female tenure rates a bit later in this chapter. But with respect to the relative loyalty of Young People, it’s telling that young female workers are more loyal than they have ever been. Indeed, 2010 is the high-water mark for women in the workplace, at least as far as tenure is concerned.

The numbers don’t lie. Today’s Young People are as loyal or more loyal to their employers than at any time since 1966. You could argue that the recent recession has had something to do with it, but because that recession has affected people at every age level, it doesn’t seem a particularly relevant argument. You could argue the validity of these statistics, but the Bureau of Labor Statistics is hardly a biased source. Or you could concede that the Youngest members of today’s workforce are actually more loyal than anyone wants to give them credit for.

Oh, and you remember the seemingly outrageous 6.3 jobs that today’s Young People have before their 25th birthday? Well it turns out that the average Baby Boomer had 5.5 jobs before his or her 25th birthday. In fact, the typical Baby Boomer held 11 jobs between the ages of 18 and 44, which translates to a new job every 2.5 years.

R. Li’s story is a vivid example of an easily forgotten truth: For at least the past 60 years (and probably much longer than that), a certain percentage of Young People have been experimenting with several jobs before finally settling into a stable career. This is not a recent phenomenon. In roughly the same numbers, today’s Young People are behaving exactly the way today’s Old People did when they were Young People.

More importantly, today’s Young People are quantifiably more loyal than at any other point in the past 50 years. The opinion that most Older or more-experienced workers have about Young People being more capricious and disloyal than ever is simply not true.

How Is This Possible?

There are several reasons to explain why today’s Young People are more loyal than ever. As we’ve already mentioned, recessions tend to have a positive impact on worker loyalty at all age levels. When there aren’t as many jobs to go around, people are often happy simply to have a job to go to—and even if they’re not happy, it’s not like they can do much about it.

Another significant factor is the wealth of resources that today’s Young People can employ in the search for the right job. Their ability to comprehensively research prospective employers, coupled with the educational world’s increased emphasis on doing so, has made it easier for people of all ages to search for jobs that fit their particular skills and interests. Although this occasionally means that Young People delay entering the working world in the hopes of finding the “perfect” job, it also means they are more likely to stay at whatever job they find because they already know ahead of time that it’s probably a good fit.

But perhaps most importantly, today’s Young People crave permanence in their lives—probably more than at any other time since the 1950s. As we’ve already discussed, the average Baby Boomer held 11 jobs between the ages of 18 and 44, which provides an interesting counterpoint to a 2013 Ernst & Young study that revealed a full 60% of the Youngest members of today’s workforce expect to work for fewer than 6 employers. Young People are also the least likely age group to view starting their own company as the most attractive employment option, given that doing so is often a risky, uncertain, and lonely enterprise.

There’s only one way to interpret data showing that today’s Young People expect to work for fewer employees than their elders and that they are also comparatively disinterested at going out on their own. They simply want to be loyal to someone, and they’re actively looking for it.

So what do today’s Young People have in common with the workforce of the 1950s? The comparison is stronger than you might first think. Following the chaos of World War II, the collective desire to return to a normal, stable life was a powerful factor in helping create the golden age of work ethic and loyalty for which the 1950s are remembered. In the past 30 years, there has been a similarly world-altering phenomenon, albeit completely different in nature. And while it has affected all of us, its impact on Young People’s desire for connection and permanence has been greater and more profound.

I’m talking, of course, about the Internet and how it has forever changed the way we interact with and find our place in the world. The vast majority of Gen Xers (myself included) and all Baby Boomers were born before the Internet truly took off, which means we developed our sense of self in a fundamentally different world than our younger colleagues have done. The importance of that fact cannot be overstated. If you have ever struggled to understand why your Young counterparts behave the way they do, appreciating the impact of the Internet is essential.

But before we get to that, we first need to discuss a little concept called Dunbar’s number.

What Is Dunbar’s Number, and Why Should I Care?

In the early 1990s, an Oxford University anthropologist named Robin Dunbar published his findings on the limits of human social interaction. Specifically, he had set out to learn whether there is a neurological limit to the number of people any one person can actively care about. In other words, he wanted to determine how many friends, family, colleagues, and neighbors you can honestly, truly consider to be part of your social sphere.

I’ll spare you the research details, considering they involve regression analyses and confidence intervals and other statistical math that might put you to sleep, but the results were pretty clear: Human beings do seem to have an upper limit on social connections the brain is designed to accommodate, and that number is roughly 150. The actual range is probably somewhere between 100 and 230, and other researchers have argued that the maximum is somewhere around 300. However, 150 has become known as Dunbar’s number. Dunbar’s number is a scientific approximation of the number of people we’re able to care about at any given time, and in that sense it’s very similar to the 10,000-hour approximation that Malcolm Gladwell popularized in his book Outliers as the number of hours of practice you need in order to become an expert at something.

Dunbar’s estimated maximum of 150 social connections has been corroborated in a number of different and intriguing ways. The average Neolithic farming village is estimated to have had a population of around 150 people, as did the average 18th-century English village. The basic unit of ancient Roman armies? 150, which is remarkably close to the size of the modern American military company of 160. Perhaps more impressively, in 2010 Dunbar conducted a study with Facebook to analyze user habits and found that regardless of the actual size of a person’s friend network—including those with thousands of connections—the average user doesn’t interact with more than 150 of those people. Even less scientific facts such as the tendency of weddings to have 300 guests or fewer (150 each for the bride and groom) support the theory that we have a built-in mental limit to the number of social connections we can pay attention to at any given time.

The reason Dunbar’s number is important is because it addresses human connection, and loyalty is about nothing if not our connection to others. All of us want to belong to something, both personally and professionally, and it seems as though we’re generally looking for no more than 150 people with whom to connect. There are certainly some people who have more than 150 close connections, just as some people have fewer. But I’m comfortable assuming that when you think about the number of people you consider to be important to you in some way, it’s probably not more than a couple hundred.

Now, let’s look at how the Internet has changed the way we go about finding those connections—and, more importantly, why it’s possible to say with complete certainty that Young People are actively seeking a connection with you and your organization.

The Rise of the Internet and Its Effect on the Desire for Loyalty

It is impossible to overstate the impact of the Internet on the world today, so I’m not going to bother going into any detail. You already know the Internet is a big deal. I would even go so far as to say that it’s a bigger deal than sliced bread, since—let’s be honest—bread is amazing, but it didn’t take a genius to figure out that you needed to cut it in order to fit it into your face. But what does the Internet have to do with the desire of today’s Young People for loyalty?

In a word, everything.

I’m 36 years old as I’m writing this, which is as good an age as any to use as a dividing line between the two groups into which the Internet has split the world—people who came to maturity before the Internet truly took hold and people who came to maturity after the Internet became inextricably entrenched in our daily lives. This division, by the way, is a part of the reason that we Gen Xers are often characterized as being perpetual outsiders. Many of us honestly don’t know where we fit because we straddled this technological revolution.

And it was undeniably a revolution.

If you came of age in the world before the Internet, then you grew up in a world without constant connections. You played outside far more than kids do today because there was a good chance you didn’t own a video game system, and you ran or rode your bicycle to your friends’ houses to see if they were home because most of the time it was actually quicker than trying to get them on the phone.

In fact, let’s look at just how small the world of yesteryear really was.

As you can see, if you grew up before the Internet really took off, there were several years—occasionally decades—between the advent and widespread adoption of these various pieces of technological connection with our friends, family, and the rest of the planet. Also, each of these innovations was originally dedicated to a single and specific type of communication: cell phones for calling, video cameras for recording, and computers for email and other written pieces. It took the better part of 20 years for the Internet to allow for the easy transfer of images across data lines, for cell phones to allow for written text messages, and for video cameras to be packaged into desktop computers and later smartphones. Since the end of the 1990s, of course, these forms of communication have only become more and more intertwined, but that was absolutely not the case for a long while.

We talk in Chapter 6 about the accelerated pace of technological change and its impact on generational tensions. For now, what’s important to understand is that the fits and starts with which these technologies came into being, along with fairly slow adoption on the part of 1980s and 1990s consumers, means that the world Old People grew up in continued to be defined by a lack of constant connections. And what that means is that all of them—including myself and everyone else in their mid-30s or older—all of them developed their sense of self in a relatively small community. Even for people who grew up in the world’s largest cities, their community was essentially a combination of neighborhoods and elementary schools and high schools and summer camps. They had their extended families and the people who worked on the same floor or on the same shift. Those were the only people they ever came into contact with because it was simply impossible to find people in any other way. They had a few hundred people to choose from, maybe a couple thousand, and that was really it.

And in a world that size, it’s comparatively easy to carve out a position for yourself, something that grounds you and assures you that you’re noticed. That’s the world we were either evolved or designed for. Those of us who grew up in that world may not always have enjoyed the position we found ourselves in, but we at least knew that we had one.

What this means is that the area in which Old People searched for their 150 connections was relatively local. Outside of their extended families, which may have lived in other cities or states, the vast majority of the people closest to them probably lived nearby. It might not have always been easy to find the right personal or professional connections, but the search was characterized by two key factors: You knew where to look, and the population in which you were looking was a relatively small one.

The Search for Connection Goes Global

Now consider the world that Young People grew up in. Every so-called Millennial was no older than 15 in 1995, the year that the Internet became searchable and its use subsequently exploded, and many of your Youngest colleagues were still in single digits. For them, their maturation happened in concert with the exponential adoption of all these new technologies—email, cellphones, texting, online videos, and every other form of communication rapidly converging into a single portal and being utilized by an ever-increasing number of people. For a great many of them, they have literally never known another world.

And here’s what that means. For your Youngest colleagues—the ones who have always had the Internet and dozens or hundreds of television channels to choose from, who have always been able to communicate with anyone they wanted to anywhere in the world—for them, their world has always been global. It’s always been 7 billion people large, and it’s never had any real borders. That might seem like a gift, and in many ways it is.

But when it comes to making meaningful connections and finding a position in the world, a lack of borders is actually a problem. When the entire world is the community that you consider yourself to be a part of, it’s much harder to feel like you’re being noticed or that what you’re doing is interesting, useful, or relevant. In a world with limitless options for connections, when you’re sifting through a community of 7 billion, finding the 150 that you can truly attach to is a very difficult task.

What’s more, today’s Young People have also matured and developed their sense of self in concurrence with an ability that didn’t exist for anyone who is now over 35—specifically, the ability to share information about themselves with anyone in the world. Social networking sites became available (and then wildly popular) in the mid-1990s, and viral videos were a possibility well before YouTube’s 2005 debut made them almost commonplace. Suddenly, the 7 billion people in your community were all talking—and once they started, they never stopped.

First hundreds, then thousands, then millions of people posted snippets of their lives online for the rest of us to view. The diary, which a generation ago was an opportunity for self-reflection and usually intended to be read by the author and no one else, was suddenly transformed into a vehicle for self-expression and intended to be read by as many people as possible. The home movie we shared with our family and friends became an opportunity to get attention and possibly even money from millions of complete strangers. The sheer amount of information about others that is available for our collective consumption beggars comparison. Every day, over 98 years of video are uploaded to YouTube—more than 51 million minutes of watchable footage. I’m sure that’s as mind-boggling a number to you as it was to me the first time I heard it. People today are being exposed to more information about a greater number of people than has ever before happened in human history.

In Chapter 1 we talked about the “poverty of choice,” the phenomenon in which people who are given too many options often choose to do nothing. There is no bigger or better example of that than how the Internet is affecting today’s Young People. They want to be connected to others, and they want to be loyal, just as people have always wanted those things. Nothing has changed there. They have simply fallen victim to the most all-encompassing poverty of choice in human history. With all of humanity literally at their fingertips, many Young People are having a harder time than ever deciding where to devote their time, energy, attention, and loyalty.

Moreover, perhaps the most insidious part of the explosive expansion of our global community is the simple fact that people are behaving exactly as they did before such widespread sharing was possible. All of us are constantly engaging in a subtle game of propaganda with our network of family and friends. We selectively share those facts that will get us attention or sympathy or a promotion or the envy of our peers or whatever else we want, and we often choose not to mention anything we believe will paint us in an unflattering light. We’ve been doing this since the beginning of time—but now it’s available on a global scale.

The upshot is this: All day long, since they were old enough to process what they’re seeing, today’s Young People have been staring at a world that seems to be filled with a disproportionate number of people who are richer than they are, or more attractive than they are, or doing more interesting things than they’re doing, or doing those things in more exotic places, or living in nicer houses, or driving nicer cars, or becoming overnight successes. Everywhere we look, thousands of people in our global community seem to be ahead of us or happier than we are, and every day another 98 years of competition comes online to make our own accomplishments seem that much more unimpressive. The ubiquity of our global community, and our own seeming inability to keep pace, is a constant, crushing pressure inextricably linked to the world we all now belong to.

This is not solely an issue for Young People, of course. Numerous studies have shown a correlation between the amount of time a person spends on social media networks and the likelihood of that person developing symptoms of depression. Every one of us has felt at times as though our own contributions or circumstances are somehow lacking in comparison to what we see online and on television every day. Every one of us has been occasionally paralyzed or overwhelmed by this global poverty of choice. But it’s unquestionably worse for today’s Young People than for today’s Old People because Young People have never had another system. This is the only world they’ve known. They didn’t get a chance to develop very many important relationships before the Internet swept in to interfere. Don’t get me wrong: The Internet is an incredible invention, and it has brought us too many advantages to name. But when it comes to the psychological well-being of today’s Young People, there are two significant and negative side effects of our Internet-based culture.

First, it has created a world in which our natural desire to attach ourselves to a community has been made infinitely more difficult because there are now an infinite number of places to look for those connections. This helps explain why young Facebook users tend to have hundreds more friends than older people: 27% of 18- to 29-year-old Facebook users have more than 500 friends, while 72% of 65-and-older Facebook users have 100 friends or fewer. This is because those Young People are still trying to find the 150 or so connections that will eventually form their community. This also helps explain why today’s Young workers have a stated desire to work for a smaller number of companies in their career than Baby Boomers did in theirs. They want to find a place to attach to; they want to be loyal because there’s something in all of us that craves that kind of connection. They may never be able to articulate this sense of loneliness because they don’t know there’s another way to think. But something in them is hungry for a place to call home, and that desire is borne out in a dozen different ways—from their devotion to social networks and the search for community, to their preference for spending time with friends over almost any other activity, to their hope to work for as few companies as possible.

Second, the Internet has created a culture in which it is alarmingly easy to feel as though our own accomplishments aren’t as interesting, valuable, or impressive as the accomplishments of others. Again, this is hardly limited to Young People. It’s difficult for all of us to feel like what we’re doing is interesting or important when we hold ourselves up against everything that everyone else in the world is doing. But if you developed your sense of self before the Internet truly took hold, then you at least have a foundation to draw strength from. You have a grounding in an earlier and smaller world. Today’s Young People don’t. They know no other way. All they know is they’ve been dropped into an impossibly large world where everybody is shouting always about everything, and what they want—even if they don’t always know how to ask for it—is for somebody to come along and pluck them out of this endless ocean of noise and make them feel like they’re not drowning.

So there you have it. Today’s Young People are at least as loyal as Young People have been at any time in the past 50 years, and the Internet has created in them a desire to be more loyal than ever. In fact, the biggest problem that your Young colleagues currently face is that they’re not entirely certain who they should be loyal to.

And the reasons for that are literally everywhere you look.

So if All This Is True, Why Do Young People Seem Less Loyal?

While it might not be true that today’s Young People are less loyal than they used to be, there’s no denying that it seems to be true. Most of us feel as though every Young Person we hire is planning to jump ship as soon as possible. I’ve even heard stories of recent college graduates turning down jobs in favor of moving back home with their parents and not working at all. And a popular 2012 article in USA Today highlighted a Young worker who failed to meet his project deadline because it wasn’t “convenient” for him. Faced with stories like these, it’s no wonder that most of us believe today’s Young People simply aren’t interested in working hard—or maybe at all.

So why do we feel that today’s Young People aren’t loyal? The answer is simple. It’s not that Young People are less loyal than they used to be. It’s that everyone is.

And the only proof you need are in the graphs you saw a few pages ago, in Figures 4.1 and 4.2.

It’s impossible not to notice in Figure 4.1 that for all male age groups, workplace loyalty seems to have peaked around 1983, only to have fallen off precipitously in the past 30 years, except of course for the Youngest workers. So what happened in the 1980s to negatively impact the loyalty of male workers at almost every age level for the next three decades?

I’m sure you already know the answer. The 1980s introduced a culture of outsourcing and restructuring that over the past 30 years has profoundly altered the nature of the employer–employee relationship. We get into this in more detail in just a moment, but first let’s look at a brief history of corporate strategy over the past 70 years, courtesy of A Brief History of Outsourcing by Dr. Robert Handfield:

Since the Industrial Revolution, companies have grappled with how they can exploit their competitive advantage to increase their markets and their profits. The model for most of the 20th century was a large integrated company that can “own, manage, and directly control” its assets. In the 1950s and 1960s, the rallying cry was diversification to broaden corporate bases and take advantage of economies of scale. By diversifying, companies expected to protect profits, even though expansion required multiple layers of management. Subsequently, organizations attempting to compete globally in the 1970s and 1980s were handicapped by a lack of agility that resulted from bloated management structures. To increase their flexibility and creativity, many large companies developed a new strategy of focusing on their core business, which required identifying critical processes and deciding which could be outsourced. Outsourcing was not formally identified as a business strategy until 1989 (Mullin, 1996). The use of external suppliers for...essential but ancillary services might be termed the baseline stage in the evolution of outsourcing. Outsourcing support services is the next stage. In the 1990s, as organizations began to focus more on cost-saving measures, they started to outsource those functions necessary to run a company but not related specifically to the core business. Managers contracted with emerging service companies to deliver accounting, human resources, data processing, internal mail distribution, security, plant maintenance, and the like as a matter of “good housekeeping.” Outsourcing components to affect cost savings in key functions is yet another stage as managers seek to improve their finances.

To put it in simpler terms, many companies have moved from a model that favors growth (“own, manage, and directly control,” “broaden corporate bases,” etc.) to a model that favors efficiency (“increase flexibility and creativity,” “identifying critical processes,” etc.). In a growth model, employees are a necessary and indispensable piece of the equation; after all, how can you even pretend to be growing if you don’t have more and more employees all the time? In an efficiency model, however, employees are an expense that should be managed with the same impartiality that you might use when deciding whether to update your software or scrap your outdated and costly heating system.

But what about professional women? Doesn’t their graph (refer to Figure 4.2) tell a different story? On the surface it does. Women have been entering the workforce in greater and greater numbers for the past 40 years, and they are staying in their jobs longer than ever. That is to be commended.

But what should not be commended is this: Despite the fact that women are more likely to have a college degree than men (37.1% vs. 34.9% in 2010), they are almost twice as likely as men to work in a part-time capacity (26.6% vs. 13.4%), and they still earn less ($669/week vs. $824/week). Also, because women are more likely to work part time, they’re less likely to have workplace benefits. Unfortunately, the rise in female tenure rates also correlates with the increasing desire of businesses everywhere to cut costs wherever possible.

To summarize Dr. Handfield (and also to butcher Rousseau), the social contract between employers and employees has evolved in a way that has made the cultivation of loyalty in the workforce a more difficult issue than ever before.

Why? Because no one will be loyal to you if you are not also loyal to them.

Loyalty Is a Two-Way Street

Loyalty does not exist in a vacuum, nor has it ever. Loyalty doesn’t just happen. It’s a quality that’s cultivated, something we prove to each other over and over and over as we move along the spectrum from jobseeker to applicant to new hire to trusted employee to indispensable lynchpin of your company’s success. The reciprocal nature of loyalty is one of the easiest things to forget when it comes to dealing with others, but we forget it at our own peril.

This is true in our personal lives as well. If you are married, you will admit that you were not loyal to your husband or wife when you went on your first date together. The loyalty you share developed slowly, over time, as both of you gave each other reasons to want to become a permanent couple. Your children are not loyal to you simply because you adopted or gave birth to them. They develop that loyalty as you feed them and care for them, as you take an interest in their lives and buy them school supplies and comfort them when they have bad dreams and help them decide where to go to college. In everything that we do, loyalty demands proof.

Similarly, if you are loyal to your current employer, it is at least in part because your employer has done things to earn that loyalty. Maybe they’ve given you a pension or tuition reimbursement or paid vacation. Maybe they kept you on during an unexpected downturn and let you know that they would fight for you when things got tough. Maybe they’ve guaranteed you a percentage of the profits when your startup finally takes off. Maybe they’ve done nothing for you that they haven’t also done for everyone else they employ. At the absolute minimum, they promised you job security and then delivered on it. And as a result, you slowly became a loyal member of the team.4

4 Conversely, if you don’t feel any particular loyalty to your current employer, it is at least in part because they’ve done things to make you feel that way. We’ll be talking about that in a few pages.

In fact, wherever you find loyal workers, you will always find a corporate culture with tangible examples of its determination to earn that loyalty. Consider the military, which is undeniably a system in which loyalty is encouraged and rewarded. While it may be true that a sense of duty and higher purpose animate those who choose to serve, the military itself doesn’t rely on noble beliefs to encourage loyalty. It offers educational benefits, pensions after 20 years of service, job placement programs, support groups for family members, discounts on food and other necessities, and several other programs. Those things are part of the reason you still see fifth-generation military families. In much the same way, pensions, flex time, in-building daycare, and other perks are part of the reason employees are loyal to their employers. Wherever you go, loyalty is always an earned thing. It’s never a given.

Thus, the expectation of immediate loyalty from your newest employees is completely unrealistic. They simply have not been around long enough for their loyalty to have been firmly established.

This is not an age-specific thing. There is nothing about being older that inherently makes Old People more loyal than Young People. Former Enron employees of any age were very unlikely to immediately display an unquestioning loyalty to their next employer after watching their life savings disappear. Loyalty is more a function of experience than age, although it so happens that as we get older, we have more time to develop a mutual sense of loyalty with our family, friends, and employers. However, if anything occurs to shake that sense of loyalty, Old people are just as likely as Young ones to become disloyal and unmotivated.

Confirmation of this fact comes from the Center for Work-Life Policy, which found that the proportion of employees professing loyalty to their employers slumped from 95% to 39% between June 2007 and December 2008, while the number of employees who expressed trust in their employers fell from 79% to 22%. Obviously the recession—and, more importantly, the business world’s response to it, which in most cases involved punishing rounds of layoffs—had a massively negative impact on worker loyalty. And not just on Young workers. In fact, among all generations surveyed, Baby Boomers exhibited the highest levels of discontent with their employers.

The evidence is ironclad. If you want loyal and hardworking employees, regardless of their age or experience, you can’t just sit idly back and expect it to happen. You have to earn it. If you are dealing with Young People who have not had the chance to see the benefits of being loyal to you, then you’ll have to work harder to persuade them than you will with your Older or more-experienced colleagues and employees.

Why all this work? Because if you are the employer, you need to begin this process. You need to show both Young People and Old People that yours is the kind of department or company worth being loyal to. Once you do that, your employees will respond by becoming loyal and giving you all the advantages that loyalty typically confers—dedication, productivity, advocacy to your customers, etc.

So the real question is, are you doing everything you can to prove to others that you deserve their loyalty?

Unfortunately, the answer is probably no.

What We Used to Hear About Work, and What We’re Hearing Now

Over the past 85 years, employers have devised several ways to successfully encourage employee loyalty. Here are a couple:

• From 1929 to 1932, at the height of the Great Depression, only 3% of workers with company pensions saw their pensions disappear, and the number of companies that offered pensions actually increased by 15%.5

5 As we’ll soon see, this is a far cry from how the average company handled the recession of 2007–2009.

• From 1940 to 1960, the number of workers covered by private pensions swelled from 3.7 million to 19 million—fully 30% of the workforce. By 1975 that number had increased again to 40 million, or almost 80% of all employees.

These are the kinds of corporate behaviors that help create a dedicated, hard-working, loyal workforce. When employees know that you’ll be there for them through thick and thin, they’ll show their appreciation by working harder and looking less often for other jobs. It’s as simple as that.

This is the story of the 1930s through the 1970s. Outsourcing didn’t exist as a defined business strategy, and so employees didn’t worry that their jobs might disappear overnight. Pensions were a firmly established facet of business, and more and more companies offered them as a way to attract the best workers. Real wages were rising all the time. For these and other reasons, employees felt as though their employers actively cared about them, and they repaid their employers with loyalty. There were bumps along the way—most notably recessions, when even the most conscientious employers are sometimes forced to cut staff—but overall the trend during these five decades involved companies providing more and more benefits to their employees, which in turn yielded higher and higher loyalty from those same employees.

Sharon’s story is typical for people her age. When a company goes out of its way to take care of its people, the people respond with loyalty, pride, and hard work.

Since the 1980s, however, the dynamic between companies and their employees has been a markedly different one. The stereotypical picture of the employer–employee relationship that has been handed down to us from the 1950s—ironclad job security, comprehensive benefits, regular raises and bonuses,6 little if any job hopping—has been replaced. For today’s Young People and Old People alike, here are the workplace realities:

6 Often in the form of a holiday ham. Why don’t people give meat as bonuses anymore?

• In 2012, Duke’s Fuqua School of Business found that almost 75% of respondents indicated labor cost savings as one of the three most important drivers leading to overseas outsourcing, twice the rate of response for any other option. Also, despite the fact that rising labor costs overseas are shrinking the cost gap between employing workers at home vs. workers abroad,7 only 4% of large companies have any plans to return jobs back to the United States.

7 By 2013, the cost gap between U.S. and China is expected to be only 16%. That means that companies which choose to outsource to China are employing 7 Chinese workers when they could instead be employing 6 U.S. workers for the same overall cost (once shipping, fuel, infrastructure and other costs are factored in).

• Between August 2000 and February 2004, manufacturing jobs decreased for 43 consecutive months, the longest stretch since the Great Depression. More than 8 million manufacturing jobs have been lost since the 1990s.

• The U.S. Department of Commerce revealed that during the 2000s, America’s largest companies (accounting for 20% of all American workers) cut their workforces in the United States by 2.9 million while increasing employment overseas by 2.4 million.

• Inflation-adjusted median household income has decreased every year since 2007. It peaked in 1999 and has not reached that level in the subsequent 15 years.

• In 1983 there were 175,143 pension plans in America; by 2008, there were only 46,926. Also, as recently as 1998, fully 90% of Fortune 100 companies offered defined benefit plans to their new salaried employees. By 2009 that number had fallen to 19%, and by 2013 it was 11%.

• A 2011 Aon Hewitt survey found that of the companies that still offered traditional pension plans, only 44% of those plans were made available to their new hires.

• Twenty-five percent of the jobs in America pay less than $23,050, the federal poverty line for a family of four.

• Since the 1970s, temporary employment has skyrocketed through every kind of economy, from 400,000 a day in 1980 to nearly 3 million by 2000.

• The percentage of contract workers in the United States has increased almost 500% since the mid-1980s. Also, 42% of employers planned to hire temporary or contract workers as part of their hiring strategy in 2014, a 14% increase from 2009.

• Of the 8.8 million jobs lost during the 2007–2009 recession, 60% paid between $14 and $21/hour. Of the jobs that have been regained since 2009, only 27% of them pay between $12 and $21/hour. The majority of new jobs (58%) pay less.

This is the working world of today, the one Ellen described in her story, one in which employees have been reimagined as an unwelcome and overpriced expense that should be reduced at every opportunity and with every available tool—or, rather, an expense that is being reduced at every opportunity and with every available tool. Unfortunately, the prevailing notion of what work is today is one in which everyone is being expected to fend for themselves. The idea of corporate loyalty is disappearing from the top down because the major incentives that foster employee loyalty—benefits and job security chief among them—are being taken away. Every single one of them. And it is flatly impossible to properly express how big an impact this has on the loyalty of those you work with and lead.

Moreover, the world I’ve just described is quite literally the only world Young People have ever known. The increasingly disloyal relationship between employer and employee is, for them, the only one that has ever existed.

What Does This All Mean?

This cannot be overstated: Young People have never lived during a time when the business world was trending toward more job security, more pensions, more health benefits, or more certainty that their hard work would be repaid in any appreciable form. In fact, virtually all of them began their professional lives after the dot-com bust of the late 1990s, which is when the disappearance of all these incentives really started to accelerate. For them, the only world they have ever known has featured layoffs, outsourcing, automation, Enron, and the disappearance of the middle class. It’s all they’ve ever heard—and with the exponential growth of the media, they hear it significantly more often than they would have 10 or 20 years ago. Some of them may even have seen their parents lose their jobs in the name of efficiency, and they’re wary of devoting themselves to an employer only to have the same thing happen to them.

In addition, your Young employees are often working on teams with Older colleagues who have more comprehensive benefits than they do—not because the Older ones did anything special to earn those benefits but because those benefits are simply no longer available. Most new hires are entering the workforce with no expectation of ever participating in the various safety nets that many of their Older colleagues are counting on to help sustain them through retirement. When Young People see a company that used to offer a variety of benefits to its employees but has decided not to do so anymore, what other conclusion can they reasonably draw than that the company they work for doesn’t care as much about its people as it did in the past? How else are they supposed to interpret the rising cost or outright disappearance of employer-sponsored health insurance plans except as an indication that companies aren’t as invested in their workforce as they used to be?

If you add all this up, the message that Young People are hearing is that they’re supposed to do the same work as everyone else, but they’re supposed to do it for less reward. What they’re hearing is exactly what an Old Person would hear if her boss walked in one day and said, “I’d like you to keep doing the same job you’re doing now, but I’m going to pay you 15% less. The economy, you know.” It hardly needs to be said that such a conversation would have an immediately negative impact on both her work ethic and her sense of loyalty to that employer.

There are multiple valid arguments to explain why the working world has changed in the ways that it has. The rise of the global economy demanded drastic solutions like outsourcing to reduce operational costs in order to stay internationally competitive. Pensions had to evolve in the face of changing workplace demographics. The elimination of jobs through automation is a natural extension of an effort to keep prices at a level that consumers are willing to pay. All of these statements are true.

But they are also all beside the point. What’s important is that an ever-increasing majority of the workforce is being trained to believe that their employers are not going to care about them; and for your Youngest employees and colleagues, that opinion is the only one their experience will justifiably allow.

Make no mistake: Today’s Young People want to be loyal. We’ve seen the proof of that already. But they don’t enter the workplace as a tabula rasa that you can shape as you wish. They enter with preconceptions based on what they’ve seen and heard, just as people have always done. Unfortunately, what many Young People have seen and heard has caused them to start their professional lives with a deficit of trust. It’s a deficit that has been built into them their entire lives and which in most cases has literally nothing to do with anything you have ever specifically said or done to them.

Bottom line: You’ve got Young People coming in to your company who are simultaneously desperate to belong to something and who have been trained to believe that you’re not going to care about them. This explains in large part why they don’t immediately display a deep sense of loyalty or the killer work ethic that is loyalty’s natural accomplice.8 They simply don’t want to put in a great deal of effort only to find their job outsourced or automated six months down the road. They don’t want to start off as a contract worker and give it everything they’ve got, only to learn that there’s not enough money in the budget to turn their contract into a full-time position with benefits. They want to know that they’re going to be rewarded for what they do—and in that sense, they are exactly like everyone else.

8 Part of the reason is because they’re lazy and have completely unrealistic ideas about how quickly their careers are likely to advance, which we’ll be discussing in greater detail in the next chapter. Don’t worry, Young People—your moment is coming!

The point is, if you feel that your workforce is not as loyal or hard working as you’d like them to be, you absolutely must consider what messages you’re sending to make them feel and act the way they do. Some of the problem is on their shoulders, and we discuss that in Chapter 5. But some of it is also on yours. It’s your job to show your employees, both Young People and Old People, that what they’ve seen happening in the world around them is not the way you operate. If you want their loyalty, you have to earn it. That’s the way it’s always been, and it’s more important now than ever before.

So What Can You Do?

Hopefully you now appreciate both the reciprocal nature of loyalty and the major reasons workplace loyalty and work ethic seem to be on a steady decline. If so, you might be feeling overwhelmed. After all, the entire working world of the past 30 years seems to be conspiring against you to make finding loyal and hard-working employees all but impossible.

But it’s actually much easier than you think.

First, you need to get closer with everyone you work with—Younger or less-experienced and Older or more-experienced people. Remember, the first step to resolving generational issues is to determine all the things Young People and Old People have in common. And when it comes to loyalty and work ethic, we’re all on the Us side of the spectrum in several ways.

As you can see, Young People and Old People really aren’t that far apart on this issue. We all have the same motivations, and we all respond to our environment in the same way.

Now for the second step—explaining why each generation thinks and behaves the way that it does. Fortunately, when it comes to loyalty, there are very few differences that separate Young People from their Older or more-experienced colleagues, and the reasons for those differences aren’t complicated at all.

If you can see the several similarities between your Young and Old colleagues, and if you appreciate the reasons that each group thinks and behaves the way they do, then you are well on your way to eliminating loyalty as a divisive issue between the various members of your team, department, and company.

So if one of your Older or more-experienced colleagues has irritated you by expecting you to work harder than you think you’ve been given a good reason to, try instead to see their persistence for what it really is: that they themselves have been rewarded for their hard work, and they believe you will be as well. Or if your Younger or less-experienced colleagues have frustrated you with their apparent disinterest in working hard, try instead to appreciate that they are still uncertain whether loyalty to you or your company actually makes sense. They want to be loyal, but they don’t want to be taken advantage of—any more than you do.

You’ve heard it said before that people don’t leave companies—they leave people. Too many surveys to mention have found that the top two nonfinancial determinants of job satisfaction are a person’s relationship with his or her immediate superiors and his or her relationship with immediate colleagues. We want to connect with others. All of us, Young People and Old People alike, have a biological imperative to do so. But if all of us only have room in our brain for 150 of those connections, how are you supposed to earn your way onto others’ privileged list?

Easy. The same way that our family and friends do it—by caring about colleagues as people. If you want to inspire loyalty in others, and if you want them to repay you with hard work, you simply must show your employees and coworkers that you care about them as people, not just as pieces in your corporate moneymaking machine. This is true for Young People and Old People alike. If they see you taking an active interest in their lives and career, if they feel you’ll go to bat for them when necessary, they’ll be loyal to you. If instead they feel that you’re using them as a placeholder until you find a better or cheaper alternative, they will repay you by using you as a placeholder until they find a better job.

Perhaps your company still offers pensions and comprehensive health insurance. Perhaps you’ve hired your Young People as full-time employees rather than on a contract or temporary basis. Perhaps your company is well known for having resisted the temptation to outsource dozens or hundreds or thousands of jobs. If so, you’re already doing a lot to earn the loyalty you’re looking for. But even if you are doing these things—and especially if you aren’t or can’t afford to—there are still a lot of ways to develop your people into loyal, dedicated, and hard-working individuals.

And here are some simple strategies you can use now. If you’re an Old Person, many of these will help you earn the loyalty of your Younger colleagues. If you’re a Young Person, many of these will help you discover the benefits to becoming as loyal as you possibly can. And the best thing is, none of them will cost you a dime.

Remember, the people you work with, Young People and Old People, want to be loyal. They’re looking for it. All you need to do is give them reasons to believe that their loyalty won’t be misplaced, and you’ll soon find yourself with a more loyal and more productive workforce than you’ve ever thought possible.

And that, I believe, is everything that needs to be said about the nature of loyalty and its effect on work ethic. Congratulations on making it this far! You’ve now survived the longest chapter in the book. From this point forward, you are much less likely to do that thing where you flip through the next several pages to see how close you are to the end of the chapter and get increasingly annoyed as you realize it’s farther away than you want it to be.

Hopefully you’ve seen that the fundamental drivers of loyalty aren’t really generational issues at all. On these points, Young People and Old People are actually quite similar—which means that the strategies that work for one group will often work just as effectively for the other.

If you are an Old Person, you may have noticed that you’re being asked to do a little more than your Younger or less-experienced colleagues. The reason for this is simple: Employers must be the ones who create an environment conducive to fostering loyalty, and employers are almost by definition Older or more-experienced than the people they’re employing. However, in Chapter 5, it will be Young People who end up having to do more, for reasons that will make perfect sense very shortly. See? It all evens out, which is the way it has to be if we’re going to solve all these generational issues once and for all.

And why will Young People be shouldered with such a burden? Because Old People tend not to expect to become CEO after three weeks on the job, but some Young People do. It’s undeniable that many Young People have completely unreasonable expectations when it comes to how long and hard they’ll have to work in order to move up through the ranks, and their approach to career advancement is probably one of your major sources of generational tension. If the quiz in Chapter 3 revealed you to be an Old Person, then we’ll be talking about why your Younger or less-experienced colleagues think the way they do and what you can do to set them straight.

But if you happen to be a Young Person, then get ready for a healthy dose of reality. Your moment of truth approaches!