Chapter 3. Analog Methods in a Digital Age

I, a designer of Planet Earth, in order to form a more perfect creative process, establish drawing skills, ensure design tranquility, provide excellent art, promote conceptual welfare, and secure the blessings of creative liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this chapter for the designers of our world.

Don't Be a Tooler

I graduated from art school in 1986. Even though the program was specifically geared for training graphic designers, we had to take drawing and illustration classes regardless of if we ever wanted to become professional illustrators. At the time, our industry fully realized the importance of drawing as it relates to design.

But times have changed. Most art schools that offer visual communications degrees don't require students to take any drawing classes. The majority focus on software-oriented design (a tool-driven process), which only compounds the problem.

This issue isn't relegated to the realm of just recent design school graduates, however. Even seasoned designers who have been trained to draw have sometimes been lulled into creative torpor by the ease and accessibility of digital tools as well, either occasionally or permanently.

This dumbing down of creativity in our industry is a serious pet peeve of mine. Those who bake down the creative process so it's not too demanding on the individual believe the computer and not the artist is the wellspring of creativity.

The fundamental problem for many designers is the lack of a well-defined and systematic creative process. In today's design reality, it's far too easy to fall into the routine of jumping on the computer as the first step in a creative task. We've all been guilty of this at one time or another. But any designer who jumps directly onto the computer is what I would call a ”tooler.”

A tooler is someone who doesn't necessarily want to improve his or her drawing skills, but who thinks that by learning the latest software version, or applying a new pull-down menu effect, or running a filter in a certain way, or mimicking some other type of convoluted Fibonacchi-esque computer process, he or she will be able to actually skirt drawing.

Toolers don't draw. In making that choice, they not only lessen the quality of the final product, but they also fail to grow as designers. It's a lose-lose situation.

Analog—that is, drawing—and digital are not independent of each other when it comes to creating artwork. Nothing I do is fully digital, nor is it fully analog. I'm constantly going back and forth between the two throughout the creative process.

I Get Paid to Draw

Early in my career (pre-computer), people would ask me what I did for a living and I'd say, ”I'm a graphic designer.” The usual response was something like, ”You get paid to draw? I can't draw a stick figure,” and they'd proceed to admire, recognize, and clearly associate my core skill and craft with what I did for a living.

But now (post-computer) when I tell people what I do, the normal response tends to be something like this: ”That's cool. I have a computer, too. I printed some inkjet business cards for...” And they proceed to associate what they do on a hack PC in their spare time using Microsoft Paint, prefab templates, Comic Sans font, and clip-art with what I do as a professional for a living.

Gone is the appreciation or even recognition of a skill or craft we as artists possess to do our jobs. For the most part, toolers don't view themselves as lacking any core ability as ”designers” because the computer, in their minds has replaced the skill and craft they once associated with an artist's ability.

Our industry is now inundated with toolers who reinforce this poor public perception of what we do. Toolers don't take skill and craft seriously. In essence, one could argue that they are merely glorified amateurs who just know more about the software than the general public. Mom and Pop see what they produce and say to themselves, ”Hey, I can do that, too.” And thus the tooler dispensation was born.

FIGURE 3.1 Stop looking for ideas in pulldown menus and start improving your analog drawing skills.

As I stated in the introduction of this chapter, I don't expect every designer to be a full-blown illustrator, but I do think every designer should integrate basic drawing skills into the creative process in order to create to his or her fullest potential (FIGURE 3.1). This chapter will help you understand the importance of working your ideas out in analog form before moving to digital—that is, working your ideas out on paper before ever approaching the computer.

Concepts and Ideas

I teach digital illustration at a local college, and I tell all of my students on the first day of class that I cannot teach them to be creative. I can only show them methods that will aid them in their quest to create and execute unique concepts and ideas.

A tome could be written on the subject of idea generation and how someone uses creative thinking and mental problem solving within a design context. Suffice it to say that this book is geared to facilitate the execution of your ideas and not the creation of them.

Every creative process has a beginning. A solid creative foundation starts with research, knowing your audience, and thinking through ideas that are appropriate for that audience both strategically and aesthetically. Only then can you begin to draw.

Your brain is the only computer you need at this point. You're mining, not refining, so it's important to load the chamber (your brain) with as much relevant information as you can in order to fuel your creative exploration as you draw out your ideas (FIGURE 3.2).

FIGURE 3.2 Everyone has a potential super computer sitting in-between his or her shoulders. Load that computer with as much information as possible so you can draw on it when needed (pun intended).

Analog Tools

As I draw out my ideas and work through the creative process, there are three main tools I depend upon every day (FIGURE 3.3):

1. 2B pencil for roughing out concepts and chewing on.

2. Ballpoint pen to quickly create thumbnail sketches.

3. Mechanical pencil for drawing out my refined sketches, which I then scan and build upon in my vector drawing program.

I also like to use a black Sharpie and a red pen as I work, but those don't play a part in the foundational stage of my creative process. I use them in refining my artwork, as you'll see later.

The Lost Art of Thumbnailing

I love the term ”thumbnailing.” It's an apropos term to define the capturing of ideas in a simple and small (thumbnail-sized) drawing. Because you're just mining for concepts at this point, you don't need to worry about how precise or technically accurate the image is. Thumbnails are nothing more than visual triggers to help you explore the creative possibilities.

Think of the process as ”brain dumping.” You're simply opening up the floodgates of your mind and letting the ideas flow out on to paper. Have fun with the process: Don't get hung up on how appropriate the concept is at this point or how good the sketches are. You'll go through and refine your direction later.

You could also refer to these as doodles. In reality, the only difference between a traditional doodle and a thumbnail sketch is that one tends to be purposeful and the other merely spontaneous or random, lacking a focused intent. But if calling these sketches ”doodles” takes the pressure off, then go for it.

An aside: As much as I try to specifically plan for a project, I never know when inspiration will hit me. Many times something I see or think will trigger an idea and I'll grab a pen and whatever paper is handy to thumbnail the concept out and just capture the idea. This is why you'll see different ink and paper colors in my thumbnail sketches (FIGURE 3.4).

FIGURE 3.3 If the pen is mightier than the sword, then it's a safe bet the mouse is no match for it either.

Thumbnails may start out very crude, but through a process of refinement they lead to well-crafted and precise digital artwork (FIGURE 3.5).

FIGURE 3.4 Thumbnails-o-plenty.

FIGURE 3.5 Thumbnailing forms the foundation for any type of creative project, be it pattern design, custom lettering, character design, tribal illustration, icon design, or a logo mark.

More Is Better

You can never have too many thumbnails, but you can have too few. Always push yourself to create more than what you need for any given project. This will ensure you've fully vetted your exploration.

”Nothing is more dangerous than an idea when it is the only one you have.” - EMILE CHARTIER

There's a nice fringe benefit to over-thumbnailing: Over time, you'll build an archive of ”homeless” ideas. When a new project comes along that aligns with a previous project's theme, you can harvest ideas from your unused archive. It's like renewable creative energy!

An Exception to the Rule

That said, there are exceptions. Not all projects need lots of thumbnails. Sometimes the design motif is iconic and simple and you don't need to refine it beyond your initial thumbnail sketch.

A creative process should be flexible enough to allow this approach without compromising the end results. It obviously won't apply to every job you work on, but in the case of my ”Freedom of Speech” project, it did (FIGURE 3.6). The speech bubble element was clearly going to be an ”easy-to-build” object (FIGURE 3.7).

FIGURE 3.6 My concept was a very graphic and stylized speaking bubble that also read as an eagle.

FIGURE 3.7 Final ”Freedom of Speech” design.

This project was built primarily using basic shapes within my drawing program. In essence, why try to draw a perfect elliptical shape when there's a tool that already does it with precision? This applies to the star shape as well.

This project is, of course, the exception, not the rule. More often than not you'll want to thumbnail out your ideas and then redraw and refine before trying to pull off the vector artwork.

Refine Your Drawing

![]()

Before you'd get into your car and drive somewhere you'd never been to before, you'd likely check a map for directions. If you didn't bother getting a map, you'd probably get lost, drive a route that was not very efficient, and experience a lot of frustration trying to figure things out on the fly.

The same is true when it comes to building vector artwork. Drawing out and refining your ideas will give you a precise road map that you can then follow within your vector drawing program. It removes the guesswork out of building your art (FIGURE 3.8).

But if you don't take the time to think through and draw what you need to build before you build it, you'll waste a lot of time noodling around looking for that result you're after. If in doubt, redraw on paper.

Refinement is a process of evolving your art from a rough idea into a clarified plan from which you can build.

But if something just doesn't look right after redrawing your art as you refine it, then it's a good bet you need to rework it more. Whenever you're in doubt about how your drawing looks, redraw it (FIGURE 3.9).

Refinement isn't a task reserved for just this stage of the creative process: it should blanket the whole process. A smart designer will learn to art direct him- or herself over time and make continual refinements along the way (FIGURE 3.10).

FIGURE 3.8 Thumbnail sketch for character design.

I find it a lot easier to draw on vellum and use a light box. I usually only redraw the parts of a drawing that I don't like and then just tape the various ”right” parts together to form the final refined sketch that I can scan.

This process takes dedication. If you're not used to working this way, it will seem foreign, but hang in there. Over time it will get easier, and you'll get better at it.

You may invest more time upfront, but in the long run it will save you even more time, expand your creative skill sets, and produce better work.

FIGURE 3.9 A more refined version of my original thumbnail, shown on the previous page.

FIGURE 3.10 Final refined sketch I'll now use as my road map to build upon in my vector drawing program.

Create a Better Road Map

Have you ever tried to follow a map that wasn't accurate? It kind of defeats the purpose. The same is true when you draw out your refined artwork. The more precise it is, the easier it will be to build it in vector form. Once you're happy with your drawing, you can scan it into your vector drawing program.

The following project is one that shows how to build an accurate road map (FIGURES 3.11–3.14). Its earlier thumbnails are shown on the two previous pages.

FIGURE 3.11 This more refined version is closer to what I need but it still could be improved upon. The amount of time you'd spend finessing vectors would take more time than just redrawing it in a more precise form on paper.

FIGURE 3.12 All guesswork has been removed. You now have a clear road map of where to place your points and how your vector paths should be built.

FIGURE 3.13 My refined final sketch has enabled me to build my artwork with precision. In other words, analog equips digital to be more effective.

FIGURE 3.14 Final precise vector artwork of my character design. (Kanji: Create!)

This sketch-and-refine process can apply to any type of design project that needs to end up in vector form. In this example, we're showcasing a custom hand-lettered logotype design (FIGURES 3.15–3.21).

FIGURE 3.15 A thumbnail sketch establishes a direction for my logotype design.

FIGURE 3.16 Rough sketching and refining my concept. I'm not worrying about precise shapes at this point; I'm just trying to flesh out the look and feel and balance the weight of the letterforms and negative space.

FIGURE 3.17 I start drawing out my refined sketch. I'm now thinking about vector shapes. How will I go about building this in vector form? Drawing my art precisely in analog facilitates the building of it in digital.

FIGURE 3.18 Final refined sketch ready to scan in and place in my drawing application.

FIGURE 3.19 Using my refined drawing as my road map to build my vector shapes with precision.

FIGURE 3.20 I print out my concept and, using a Sharpie, I experiment with various details. Once I have my art tweaks nailed down, I'll reference it and make the changes to my digital files. This is a good example of analog and digital working together.

FIGURE 3.21 Final custom logotype design.

Back and Forth

![]()

Here's another instance that illustrates why the analog-to-vector process is essential. For this project I had to illustrate a three-eyed monster in a pseudo woodcut style. To pull off this style, I had to go back and forth from digital to analog throughout its creation (FIGURES 3.22–3.30).

FIGURE 3.22 Thumbnail sketch for ”Tri3ye Guy” illustration.

FIGURE 3.23 I drew out my vector shapes in a refined sketch before I built them.

FIGURE 3.24 My final refined sketch, ready to scan in. Since this illustration is symmetrical, I only have to draw out half of it in Illustrator. (More about symmetry in Chapter 6.)

FIGURE 3.25 No guesswork is needed as I build vector shapes. I simply follow what I've already predetermined in my refined sketch.

FIGURE 3.26 I print out my base black-and-white art and draw in how I want the shading to be built in vector form. I'll do this several times during a project in order to work out all of the detail in my illustration.

FIGURE 3.27 Here is a refined drawing of highlight detail in the figure's hair. I could have tried to render this without drawing it first, but it would have taken me a lot longer and probably not looked as good.

FIGURE 3.28 Using vellum, I draw on top of a color print-out using my light box to work out highlight details that I'll need to build out in vector form. This process of going back and forth from digital to analog becomes second nature over time.

FIGURE 3.29 This image shows a close-up of the vector detailing in this illustration.

FIGURE 3.30 Final Tri3ye Guy illustration.

Systematic and Creative

Designers create on behalf of clients. Our design solutions need to work professionally within a commercial environment. And our creative work has to fit with a client's business personality and marketing strategy. We also need to create artwork within a set budget and schedule, which means we don't have the luxury of spending as much time as we might like on any given project.

These are all reasons why a systematic creative process is necessary when creating vector-based artwork. Building your vector designs on a solid creative foundation is a must in order to produce work that is precise, on time, and effective.

The more you work systematically as you build vector artwork, the more the process becomes second nature and the faster you'll be able to execute your ideas without compromising the quality of the art.

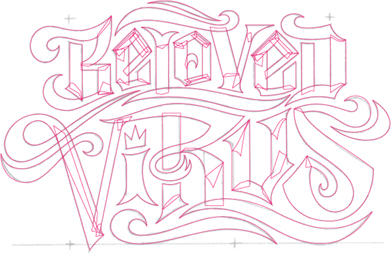

Let's take a look at this systematic process in context of creating a more complex project: a brand logo development for a new line of clothing called ”Beloved Virus” (FIGURES 3.31–3.43).

FIGURE 3.31 I helped conceive the name for this client's new business venture, so being able to then flesh out a visual representation of that name was a lot of fun. This shows a handful of the thumbnail concepts I sketched out.

FIGURE 3.32 I wanted the mark to be more timeless and less gimmicky, so I liked the idea of an ornate, hand-lettered typographic treatment. At this stage, I put meat on the bones of my idea and started defining the design. This gives me a good idea of what to expect, but it's still not good enough to build from.

FIGURE 3.33 I've now redrawn the letterforms more precisely with my mechanical pencil. I'm still scrutinizing the balance of the shapes and looking for areas I can refine even more.

FIGURE 3.34 I put the project aside for the day and approach it with fresh eyes the next morning when I find more room for improvement. I modify several letterforms and am now ready to create my final refined sketch.

FIGURE 3.35 On this specific project, I scanned in and printed out my rough at a larger size so I could redraw the final refined sketch with maximum precision.

FIGURE 3.36 I scan my final refined sketch and now have an exact road map from which to build my vector artwork upon. No guesswork will be involved; I already know what the logo should look like.

FIGURE 3.37 Whenever I build vector artwork, I form my art by creating smaller shapes. It's far easier than trying to create using one single shape. (Note: This and all of the build techniques demonstrated in this chapter will be explained in upcoming chapters.)

FIGURE 3.38 For example, look at the letter ”B.” It's made from eight different individual shapes. If I tried to build this as one or two shapes, it would be a major pain to get it built precisely. The end result wouldn't be as graceful or elegant either.

FIGURE 3.39 I continue using this same build method to create all of my letterforms for this design.

FIGURE 3.40 I call this simple method ”shape building,” and I'll go over it in more detail in Chapter 6.

FIGURE 3.41 I fuse all of my shapes together to form my base art for the brand logo.

FIGURE 3.42 Along the way, I distorted the perspective of my type treatment and nested it within a bolded outline shape. The end result is an effective, precision-built brand logo derived from the solid creative foundation of drawing.

FIGURE 3.43 The same systematic process was used to design and build all of the logo concepts I presented to my client.

If you've already determined that you can't do the drawing part of this process very well, then my book has taught you something already. You need to improve on your core drawing skills. That is what growing as a designer is all about.

I'm often asked, ”How do I get better at drawing?” The answer is easy: You start drawing now, and you stick with it. If you started drawing today (doodling counts, by the way), in five years you'll be a lot better.

One of the coolest aspects of a creative career is our talent and skill don't diminish over time. Like wine, they only get better with age. But if you never start, you'll never improve.

The whole idea behind drawing out your vector art before you build it is to create a piece of digital art that is precise and well-crafted. Your final art will just come out better.

But if that wasn't enough, vector artwork is resolution independent, which means that you can use it in almost any format or application once it has been created in vector form. It extends your design's possibilities.

I've shown you the importance of drawing out your ideas and refining them, but you've only seen a glimpse of the actual vector build methods you'll use in your vector drawing program once your drawing is complete.

You may be saying to yourself at this point, ”I can draw out my ideas, but actually building the vector art is a major pain in the ass.”

Fear not, my weary friend! The next three chapters will demystify vector building through simple systematic methods that will equip you for vector success.

Design Drills: Essential Nonsense

I'd never say that I completely understand all of my own doodles because I don't. Most just flow out of me without any forethought. I simply open up the floodgates and see what happens. It's more fun that way.

I'll admit most are strange, and some are a bit disturbing. The latter category I refer to as, ”Dark Morsels.” Once again, don't ask me what they mean because I'd be guessing, just like you.

That said, I think doodling is a great way to exercise creatively. That's why I consider doodling essential nonsense. Doodling does lend itself to practical purposes (Figure 9.1), however, because thumbnail sketches are no more complicated than doodles. The only difference is the forethought involved.

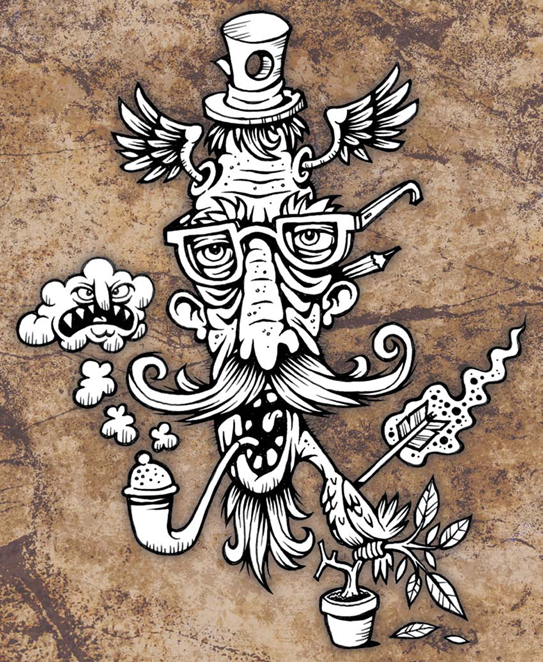

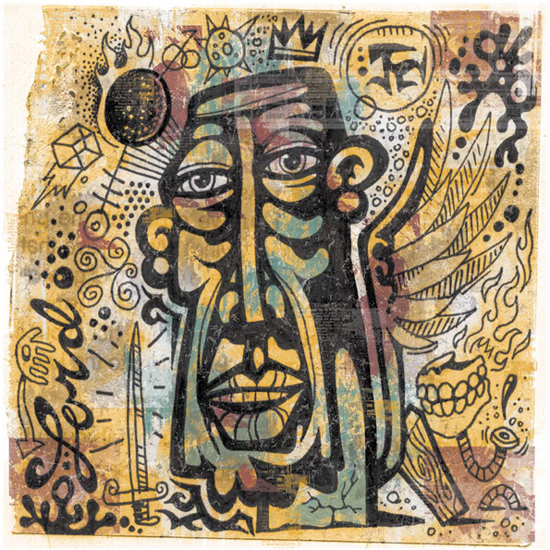

The following examples showcase a rogue's gallery of bizarre doodled characters harvested from the deepest recesses of my mind (FIGURES 3.44–3.54). I've also included a project walk-through where I show you how I narrowed down a collection of doodles and thumbnail sketches into a rather hairy self-promotional piece (FIGURES 3.55–3.59).

FIGURE 3.44 Meet Mr. Crusty Pants. He loves spinning a good conspiracy yarn.

FIGURE 3.45 A prophetic look at social media in the year 2018: Aged Twitter acolytes genetically modify themselves with bird DNA, while slinging verbal arrows and smoking government-approved big pharma.

FIGURE 3.47 Hurry up and formulate your persona.

FIGURE 3.48 Pac-Man has fallen on hard times. He also likes to swear in Klingon.

FIGURE 3.49 Sometimes current events inspire my doodles, like this incarnation of H1N1.

FIGURE 3.50 Abe's lesser-known brother Willy.

FIGURE 3.52 Stake your claim before the crazies get here.

FIGURE 3.53 Harry realizes he has a mold problem.

FIGURE 3.55 Sometimes the best marketing ideas leverage pop culture. I decided here that I wanted to draw from the hype social media was creating and produce a fun and interactive marketing piece that also served as a self-promotion for my illustration work. These are the thumbnail sketches for my idea, an illustrative mask inspired by Twitter.

FIGURE 3.56 More thumbnail sketches and the isolated direction.

FIGURE 3.57 The refined sketch, ready to scan in.

FIGURE 3.58 No guesswork vector-building using the refined sketch as our guide.

FIGURE 3.59 Final illustrative mask titled, ”Twitter Beard,” worn by my snarky daughter Savannah.