Chapter 5. Shape Surveillance

It's time to take your refined drawing out of analog and move it into the digital realm. In order to do this accurately, you must know exactly where to place your anchor points in order to precisely form the paths needed to create your final vector shapes.

It does no good to spend time up front drawing and refining the shapes in your art on paper only to fall short by building them poorly on screen. Placing points incorrectly wastes time in the build stage of your creative process, and ultimately, you end up with imprecise vector results.

I can't stress enough the importance of proper anchor point placement. You must be able to look at any visual shape, drawn or otherwise, and know exactly how you'd go about building it, anchor point by anchor point. This chapter will show you how to start the build process; chapter 6 will show you how to finish the build accurately.

The Clockwork Method

![]()

![]()

The simpler the shape, the easier it is to discern where to place anchor points. When the shapes that make up your art get more complex, however, it can get trickier.

To help you in your shape study, I've created ”The Clockwork Method” (TCM). It's a simple way to look at any shape and then know precisely where to place points. Basically, you imagine the clock face in your mind, rotate it as needed to orient with the shapes in your art, and use it as a guide.

When you initially learned how to use a drawing program like Adobe Illustrator, more than likely no one taught you where to place your anchor points when building your vector shapes. Most often the focus is solely on the tools that you use to create vector graphics and not on the creative process that utilizes the tools.

Over time and through trial and error, many are able to develop their skills enough to make it work for their needs. Most still struggle, though, to pull off well-crafted vector shapes. The source of that struggle can be blamed on not knowing exactly where to place the anchor points that make up the design you wish to create.

I know this was true for me. And it was only when I started teaching advanced digital illustration at a local college that I developed a coherent method that I could relate to my students and demystify the process of anchor point placement. The Clockwork Method circumvents all of the hassles of figuring everything out piecemeal over a period of years.

A circle provides the simplest illustration of TCM. The circle would receive anchor points at the 12-, 3-, 6-, and 9-o'clock positions (FIGURE 5.1). More complex shapes that contain both concave and convex curves won't necessarily receive all four points every time, but we'll talk about that more in a bit.

For shapes that are not straight up-and-down, you can also tilt the clock face so that it better corresponds with that shape. FIGURE 5.2 shows not only how the tilt works, but how it easily adapts to the situation and your preference in regard to anchor point placement. The 9 o'clock anchor point (highlighted blue on the left) could just as well be discerned by someone else as a 12 o'clock (highlighted green on the right) by rotating the clock in his or her mind 90 degrees instead. The Prime Point Placement, or PPP, on both is still correct using TCM. (More on PPP in a bit.) It all depends on how you see it in your mind.

FIGURE 5.1 A vector circle shape is shown at left; note how it corresponds to the clock positions on the right. I've used four different colors on the TCM clock as well as on the circle art so that you can see the correspondence here and in upcoming illustrations.

FIGURE 5.2 In this example, the 12-o'clock position is shown in two different orientations. Both are correct. Every person sees the clock orientation in his or her mind differently, but the end result is that both orientations match the curves in the art.

As Figure 5.2 suggests, your art is bound to contain many shapes, perhaps hundreds. Each individual curve that makes up the overall shape of your art will have its own custom-angled clock face.

It's just that simple and just that flexible. From now on, I want you to look at every shape you need to build in vector form through the transparent clock face of TCM. It will help remove the guesswork when you place your anchor points.

Train Your Brain

I realize this method may feel a bit strange at first, but using TCM is nothing more than a mental trick to help you look at any form, isolate the various shapes (or curves) that are in it, and associate them with a clock orientation in your mind to discern the anchor point placements.

Let's start by isolating shapes. In FIGURE 5.3 and FIGURE 5.4, you can see how I isolate particular areas of my art. Some curves define interior shapes, while some define exterior shapes. Once my visual associations with these shapes are identified using TCM, I can now properly discern my placement of the anchor points as shown in Figure 5.4.

FIGURE 5.5 provides a more challenging design for your TCM consideration. The shapes are freeform and might mentally require us to rotate and orient our clock to match its curves.

As we did in Figures 5.3 and 5.4, we'll begin to associate our mental clock with the shapes in our drawn form. Remember that when you make these visual associations, you may not use all four points on the clock to form the needed shape. If you look at Figure 5.4, you'll notice many of the anchor point placements on the left side only required one point association with the clock to form the needed curve.

FIGURE 5.6 shows how I see the first clock orientation in my mind. As demonstrated in Figures 5.3 and 5.4, I want you to continue the shape surveillance by studying the drawn art and using TCM to discern where the anchor points would be placed according to the clock in your own mind. Compare with FIGURE 5.7 and see how well you did.

FIGURE 5.3 The illustration shows how I discerned the shapes in my art using TCM. This is a step that I imagine only in my mind. The faded clocks demonstrate how I orient the faces in my mind before placing my anchor points.

FIGURE 5.4 I continue to use TCM to discern all of my anchor point placements and precisely form the path shape needed to match my drawing.

FIGURE 5.5 Look at this drawn shape and discern where you'd place anchor points using TCM. You may not need to use all four clock points on every curved shape.

FIGURE 5.6 Using TCM, I've discerned the first shape in the form. Can you discern the rest? Refer to Figures 5.3 and 5.4 for help if you need it.

FIGURE 5.7 This shows all of the final TCM locations of the anchor points. How did your discernment compare to this?

You'll build your vector art one anchor point at a time, mentally picturing the clock, rotating it if needed, and associating the point on the clock with the anchor point you need to place to form the specific curve within the drawn form. Some curved shapes may associate with one or more points of the clock; it all depends on how you visualize it in your mind. Once you've discerned an anchor point's location, you place it and then move to the next shape in your design and repeat the same process until you have the entire vector path built as shown in FIGURE 5.8.

FIGURE 5.8 This shows many of the mental TCM discernments we made as we built the vector path in order to determine the final Prime Point Placement (or PPP), which we'll cover in greater detail later in this chapter).

Applying The Clockwork Method

Of course, all shapes aren't as simple as the circle shown in Figure 5.1. And, naturally, art usually contains many shapes and curves with many different angles. Still, discerning the anchor point placement on any shape is easier if you use TCM. Regardless of how irregular a shape may be, if you think of it as a clock, you'll be able to place the anchor points with greater accuracy.

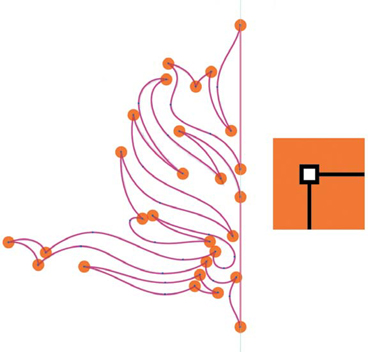

Let's try TCM on a more complex shape. Remember, the first step is to analyze the shapes in the art (FIGURE 5.9). Then, think of the clock positions and how they can be roughly approximated on those shapes. (Again, refer to Figures 5.3 and 5.4.) Because of the angles in the shapes of this flame motif, we'll rotate our mental clock to associate it with the many curves within the art.

Where do you start? The most obvious anchor point placements within any design are the areas that come to a point. Those are no-brainers, and it's a good place to start your building because you don't have to discern anything. These are absolutes: Any area of your art that comes to a point gets a point (FIGURE 5.10).

After you've identified all of the angles that come to a point, you can move on to determine the other coordinates (FIGURES 5.10–5.13).

The more you train your brain to discern shapes using TCM, the easier it gets. Like anything new, it feels awkward and strange at first, but stick with it and you'll enjoy the results.

FIGURE 5.9 The first step is to perform shape surveillance by isolating the various curved shapes and mentally associating them with a clock.

FIGURE 5.10 Most of the points in this design are corner anchor points since most of the shapes come to a point. The rest of the points associate with a mental clock orientation of 12 o'clock.

FIGURE 5.11 Here are all of the anchor points in this flame motif that match my mental clock orientation of 3 o'clock.

FIGURE 5.12 Here are all of the anchor points that match my mental clock orientation of 6 o'clock.

FIGURE 5.13 Here are all of the anchor points that match my mental clock orientation of 9 o'clock.

There are many variables that will affect the quality of your vector art, as we discussed in chapters 3 and 4. But the most important fundamental aspect of building your vector graphics starts with your anchor point locations. Get the anchor point locations wrong, and you'll have a hard time building.

We'll get into this in more detail a little later in this chapter when we discuss Prime Point Placement (PPP) later in this chapter.

More on Rotating Your Clock

As I mentioned before, when a shape within your design is angled, it helps to also angle your clock face to match it. Since this can be more confusing than a simple north/south orientation, let's consider another example.

If you look at FIGURE 5.14, you'll notice that many of the anchor points run along paths that are angled. In such cases, simply set your mental clock face to the same angle and start placing points. This is an instance for which one clock face can accommodate all of the angles. (I should point out that you could also select the vector art and your placed refined sketch and rotate them to align with a normal north/south TCM orientation. I've done that on occasion, but it isn't always practical.)

FIGURE 5.14 If a shape demands a path that needs an anchor point that falls outside the normal orientation of TCM, just rotate the TCM clock to match the angle of your shape.

Most designs that you'll build will require using both the normal (north/south) orientation and a wide variety of rotated TCM orientations, like the example in the next section.

Building Complex Shapes

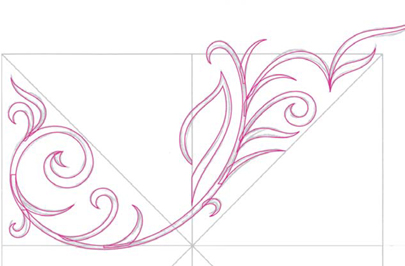

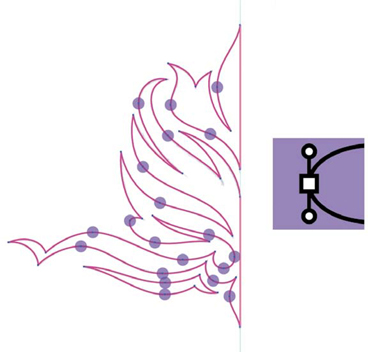

To demonstrate TCM on an even more complex shape, let's look at the elegant ornament design in FIGURE 5.15. The shapes in this art demand precise Bézier curves that can only be achieved if the anchor points are in the correct locations.

As always, TCM is the key to success (FIGURES 5.16–5.19).

FIGURE 5.15 Using TCM, I'll begin to perform shape surveillance on my refined sketch to figure out where to place my initial anchor points. The obvious locations are the corner anchor points found at each end of the vines. If your shape has a point, it'll get a point.

FIGURE 5.16 Using my refined sketch as my road map, I place my initial anchor points using TCM. At this stage, the correspondence of the drawn lines to the sketch lines underneath is not perfect. But it is the effective placement of the points that will ultimately create handles in just the right spots for pushing and pulling things into shape.

FIGURE 5.17 Once my anchor points are located in their correct positions, it's simply a matter of pulling out my Bézier curve handles to shape the path so it matches my refined drawing.

FIGURE 5.18 I continue to utilize TCM to build all of the individual shapes that make up this ornament design (points and handles are hidden here). I'm using both normal and rotated TCM orientations to pull off all of my shapes. (We'll cover shape building in greater detail in chapter 6.)

FIGURE 5.19 The final vector artwork for the ornament design.

Prime Point Placement

At the risk of sounding redundant, not to mention redundant, this bears repeating: When it comes to building your design using vector methods, it's of paramount importance that the initial anchor points you place are in the best possible locations as they relate to the shape you're attempting to form.

The paths in your final vector shape and the Bézier curves they utilize will be only as precise as the anchor points that control them. You want to make sure that the Prime Point Placement (PPP) of your anchor points is correct.

TCM will get you in the right neighborhood, but PPP will pinpoint the exact address at which your anchor point will live. Determining the exact location is a process, not an event, so you'll be leveraging both methods to fine-tune point locations.

Making a Point!

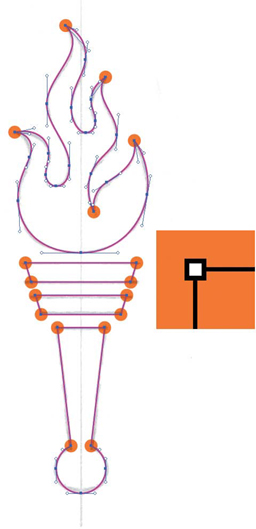

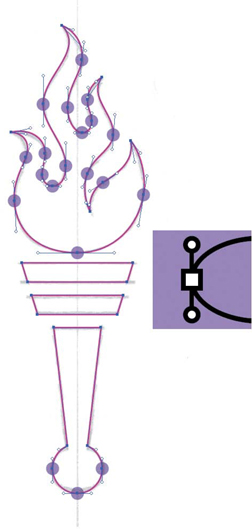

In chapter 4, we discovered there are only two types of anchor points, corner and smooth. Knowing how each controls a Bézier curve and path will help us understand where to place them using TCM and PPP.

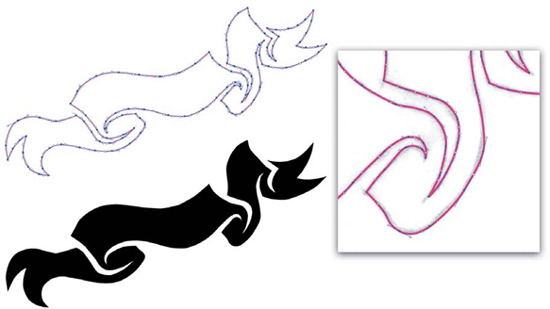

1. Corner Anchor Point: You'll place a corner anchor point anywhere your art has an apex that comes to a point. These types of anchor points can be used with or without Bézier curve handles pulled out from one or both sides when the transition between two paths doesn't need to be smooth (FIGURE 5.20).

2. Smooth Anchor Point: You'll place a smooth anchor point anywhere your art needs a curve that transitions from one path into the next. This sort of anchor point always uses Bézier curve handles pulled out from both sides to control the shape of the curve (FIGURE 5.21).

FIGURE 5.20 There are a total of 17 corner anchor points within the build shapes of this torch graphic (highlighted in orange). The handle shapes are made mostly from corner anchor points.

FIGURE 5.21 There are a total of 20 smooth anchor points within the build shapes of this torch graphic (highlighted in purple). The flame contains numerous Bézier curves, so most of the anchor points to shape it are smooth.

Combining PPP and TCM

![]()

![]()

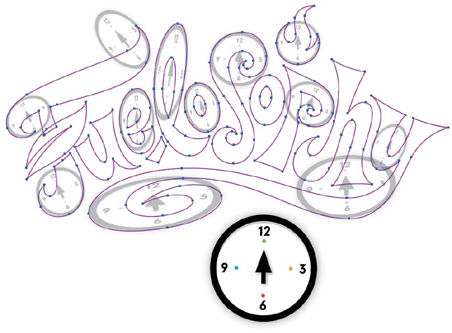

Let's take a closer look at a more complex vector graphic. Like before, we'll study the refined sketch and consider how to place our anchor points initially using TCM and then we'll use PPP to build the art precisely (FIGURES 5.22–5.25).

Note that the final design for this example (shown in FIGURE 5.25) is symmetrical, so we only have to build half of it—we'll copy the final paths and flip them to form our final art. (We'll cover more benefits of symmetrical design in the next chapter.)

FIGURE 5.22 Using TCM, I begin to perform shape surveillance on my refined sketch, discerning my anchor point placement and orienting my clock to associate with the shapes, rotating it as needed.

FIGURE 5.23 All of the anchor points in this vector ornament design are the correct type, either corner or smooth, depending on their PPP. Corner anchor points are highlighted in orange.

FIGURE 5.24 The smooth anchor points that control the Bézier curves, which bend smoothly from one side of the anchor point to the other, are highlighted in purple.

FIGURE 5.25 The final vector artwork for the ornament design was created by copying and flipping the paths created in the previous steps.

The Yin and Yang of Anchor Points

Don't assume you'll get your TCM correct all the time. No one is perfect. And when collaborating with others, you'll eventually be able to spot problem areas in their work as well. These are the most common problems:

1. Wrong Anchor Point: Make sure you are using the correct type of anchor point in your path, either corner or smooth.

2. PPP Isn't Correct: Some of your anchor points are still not in their correct positions to enable you to control the Bézier curves accurately. Go through your path and review each anchor point with TCM in mind and double check the PPP for each.

3. Not Enough Anchor Points in Path: You haven't placed enough anchor points to form the shape accurately. You are likely struggling to form the exact Bézier curves needed to make the path shape. Review your shape with TCM in mind and add anchor points on your path where needed using the Add Anchor Point Tool (+) (FIGURE 5.26).

4. Too Many Anchor Points in Path: You've placed too many anchor points to form the shape with precision. It will be hard to control the path shape and retain an elegant form. Review your shape with TCM in mind and remove the unnecessary anchor points from your path using the Delete Anchor Point Tool (-) (FIGURE 5.27). A well-built vector shape should contain only the amount of anchor points needed to pull it off. No more, no less.

FIGURE 5.26 Not enough anchor points have been placed to build the shape correctly. A telltale sign is overextended Bézier handles.

FIGURE 5.27 Too many anchor points have been placed here, which ruins the graceful shape of the design. Managing all of the small Bézier curve handles makes shaping curves a major pain in the keester.

An example: The anchor points in the design shown in Figure 5.26 are actually in their correct PPP, but the path doesn't contain enough placed anchor points to build the shape precisely. A telltale sign you're not using enough anchor points is overextended Bézier curve handles.

Trying to build precise vector paths with overextended Bézier handles is like trying to paint a picture using a six-foot-long brush. You couldn't stand close enough to your canvas to control your forms, and clearly the art would pay the price. The same is true with overextended Bézier handles. If you can't control your forms with precision, your design will wind up paying the price.

Many of the anchor points in the design shown in Figure 5.27 are in their correct PPP, but the path contains far too many anchor points to form the shape gracefully. It ends up looking clunky.

FIGURE 5.28 All anchor points are in their correct PPP, and the shape contains the correct balance of anchor points needed to create the final shape accurately. The end result is a more elegant form.

An unnecessary anchor point by definition can never be in a correct PPP. Delete the points from your path and simplify the shape.

Your ultimate goal is balance (FIGURE 5.28). After placing the anchor points and shaping the Bézier curves with their handles to form your art, you'll know immediately if you haven't placed enough or if you've placed too many to build it accurately. Be diligent in your surveillance, and you'll see massive improvements in your design.

The more you utilize TCM, the more you'll avoid these common vector pitfalls. It's important that you're able to recognize problematic attributes in your own design and the design of others you work with so you can improve the quality and consistently create at a higher level.

Deconstructing the Vector Monster

Feeling overwhelmed? Let's deconstruct a a real-world project with TCM and PPP in mind. Then you will be ready for learning the various build methods presented in chapter 6.

I created this illustration for a publishing company. Using TCM and PPP to build core shapes played a key role in building the final vector artwork.

Of course, smart vector build methods were also crucial in this project's success. We'll be vetting them more fully in the next chapter. That said, it's kind of like love and marriage: you can't have one without the other. That's why it's important to see everything in context, as we will here.

1. The Clockwork Method: First, I performed shape surveillance and analyzed the shapes in my refined sketch using TCM as shown in FIGURE 5.29.

FIGURE 5.29 Using TCM, I place my anchor points in order to form the core base shapes I need to create my artwork.

2. Prime Point Placement: At this point, I may zoom in on my anchor points and move them into more precise locations to facilitate accurate Bézier curves, as shown in FIGURE 5.30.

3. Vector Build Methods: I continue to build every vector shape needed to create my final art using TCM, PPP, and additional vector build methods that we'll go over in chapter 6 (FIGURES 5.31 and 5.32).

4. Final Artwork: Once all of my core shapes are built, I move on to coloring my vector art. Once coloring is done, I'll continue to use TCM, PPP, and additional vector build methods that we'll cover in the next chapter to build the various shapes needed for detailing my final artwork (FIGURE 5.33).

FIGURE 5.30 With my PPP locked in, I pull out my Bézier curve handles and complete the shaping of my core base shapes.

FIGURE 5.31 I build every vector shape I can using the ”Point by Point” method (which we'll cover in the next chapter).

FIGURE 5.32 All the vector shapes needed to create my final art are now built using TCM, PPP, and additional build methods that we'll cover in chapter 6.

FIGURE 5.33 The final monster vector illustration. His name is ”Blinky.”

Progressive Improvements

Building your vector shapes using the systematic creative process I describe can seem like a monstrous task even for a simple design. To manage a complex design that can easily contain thousands of points and hundreds of paths might seem impossible. But with practice and time, it gets easier and the process becomes second nature.

You'll never get your PPP absolutely correct the first time all the time. But the more you get into the habit of using TCM, the more consistently your anchor points will fall within the correct vector zip code as you build.

TCM and PPP are actually the first steps in the ”Point by Point” build method that we'll introduce in chapter 6. This process will help you even more. And in chapter 8, you'll learn how to art direct yourself, an invaluable creative and managerial tool.

Design Drills: Spotting Clocks

When you get in the habit of using The Clock-work Method (TCM) to build your vector art, you'll start to see clocks in every vector-based design you look at, whether you designed it or not. And that's a good thing.

To kick-start the habit, let's take a look at a handful of designs from my portfolio and see where the clocks show up.

FIGURE 5.34 Sometimes the clock you associate with a shape will form the entire shape, and sometimes it will just help create part of the shape.

FIGURE 5.35 This chimptastic Monkey Character Illustration Was For A kid's play area in Utah.

FIGURE 5.36 Here, I apply TCM to guide me as I build letterforms in a logotype design.

FIGURE 5.37 Logotype design concept for new line of Pepsi drinks.

FIGURE 5.38 Remember, this is a mental trick to help you discern your anchor point placements. Polly want a clock?

FIGURE 5.39 This package illustration concept for ZuPreem, an exotic pet food line, was loved by the agency and client, but ultimately it failed in test marketing.