What happens when you have to defend your organization to an outsider, all the while knowing that what your company did was not right?

How difficult is it to defend the actions of your boss to a subordinate when you disagree with the boss?

How do you handle a meeting where you know one of the participant's lies may cause great damage?

These are situations that can keep us up at night. This isn't a book about ethics; however, ethics and conflict often form a symbiotic relationship, one feeding upon the other. We face a very real dilemma when we witness something that undermines the success of the organization in the long term. The dilemma becomes even more poignant when what we observe has the potential to undermine our personal success.

This challenge isn't about those situations where laws or regulatory practices are broken. In those cases, each of us has a moral and legal obligation to take action. Still each of us has personal decisions to make and no one can guide us but our conscience. It's easy to say, "Take action!" It's the taking action that's hard. In those very difficult circumstances, I suggest you move ahead carefully, get sage and/or legal advice, and be as brave as you can be.

Here, I want to focus on those more frequent occasions where your actions might be at odds with your conscience. No laws or regulations are being broken, but the actions of another person or the organization are, you believe, unethical.

An example: A number of years ago, I was at a regional review meeting at a company I worked for, watching a dog and pony show, where key leaders of the region were reporting on business results to the national leader of the business. Also present was the CFO—my peer, the regional VP, and his two top directors. It was obvious the regional VP wanted to put everything in the best light possible. One of the four account executives stood and discussed his major accounts. One of the accounts, he boasted, had been obtained by lying to the customer. He stated this quite plainly, with a broad smile on his face. I couldn't help but notice, as he was saying this, the company values prominently displayed on the wall, in a beautiful framed plaque. After this account executive finished his spiel, he left the room. The four of us—the regional VP, my boss, the CFO, and I—were seated at the conference table.

"Is this a usual practice?" I asked the group, referring to the account exec lying to a prospect. No one answered. I pushed a little harder: "Am I the only one who is bothered by this?" To my amazement, still no one answered. Tom, the regional VP, began instead to speak on a new topic, and the meeting went on without any acknowledgment of my queries.

Unfortunately, this kind of practice was rather common at this company. I believe it was part of the reason the company did so poorly: no one trusted anyone else; the culture was one of "every man for himself." Such behavior undermines the collective focus on company goals.

Why are there so many failing organizations in U.S. business? One of the most cogent reasons is greed. Too many people share the outlook that: "Everybody cuts their own deals. I want my piece of the action, and I want as much as I can get, as quickly as I can get it. The company doesn't care about me, so why should I care about it?"

But that's building a house of cards, and, ultimately, if the majority continues to act in that manner, the house of cards will tumble down. Our entire economy almost fell all the way to the ground not so long ago, and this was after so many supposedly in the know believed there could be no down cycle.

If, instead, we deal professionally and appropriately with situations that raise ethical questions, we can support ourselves, maintain our values, and help the organizations we work for to succeed. And if we work for a firm where unethical practices are the norm, we need to ask ourselves why we are working there.

Assume you witness an activity that is clearly not kosher. This knowledge makes you nervous, understandably! It feels as if you are holding a ticking bomb. Along with recognizing that this might be unethical and/or against company's values, you also worry about yourself, even if you didn't participate in what you saw. You think, "If I say something, I could anger someone or, worse, lose my job." You might even think, "Does anyone want to hear what I have to say?"

I believe that you can say something, if you plan and act wisely. You might even come to be regarded as a hero, but that shouldn't be your motivation, and certainly isn't my motivation in telling this story. My motivation is always that the organization succeeds and thrives and that its employees are valued. In the story relating to this challenge, I demonstrate how The Working Circle can help you deal with just such a situation, without shooting yourself in the foot.

Aimee was a customer service trainer for a medium-sized electronic parts firm. She traveled to offices across the country, providing training for sales and service representatives. She had been in her job for a year and a half. Her supervisor was a no-nonsense kind of guy, who pushed hard to get the training completed and satisfy each local manager. Aimee liked him well enough, though there wasn't much socializing in the department, because everyone (three trainers) was on the road most of the time.

While Aimee was conducting a class at the Atlanta office, she was told something that upset her. The reps were bragging that their region had led the division for 12 months straight—they certainly seemed proud. Then, during a break in the class, one of the participants was talking to Aimee, and alluded to the fact that the reps had been instructed by their manager to double-count certain electronic components so that the numbers would add up to more than they actually were. Aimee listened, and then asked the rep how he felt about that.

"Not good; but what can you do? If you speak up, you will lose your job," was his response. "Besides, we get a good bonus for our production, and I don't want to lose that, either."

Aimee was disturbed by this conversation. She knew of other representatives in other regions who were working just as hard, but could not match the results of this region. Now she knew why: this region's manager was fudging the results.

During the next part of the class, she picked up other clues that led her to believe that what she had been told was true.

She called her manager in New York. (This was definitely not content for an e-mail!) She told him what she had discovered, and asked what he thought should happen.

"If management doesn't catch it, it's none of our business," Aimee's boss told her. That didn't satisfy Aimee. She had friends in other regions who weren't getting the bonuses they deserved because of the practices in the Atlanta office, dictated by its manager, who also seemed to be intimidating his staff, and made them complicit with this double-counting.

Aimee remembered other company meetings she had attended where the leadership had made a point of the high ethical standards at the firm. The last such speech, given by the COO, relayed the message that it was incumbent upon each and every employee to "do the right thing."

What to do? Aimee's manager's boss, the VP of human resources, was a rather stiff and unapproachable individual, and Aimee was a bit intimidated by her. She wondered where this VP would stand on an issue like this.

She also considered the national VP of sales, who was a gregarious, friendly man. Aimee had met him, but had not had much contact with him in the past. Still, she thought, if anyone would be concerned about this issue, it should be him!

Aimee decided to go to The Working Circle to determine what she would, or would not, do.

Before she "walked" around the Circle, Aimee reviewed the numbers for the six regions in the country. The results of the Atlanta region had far surpassed the other five regions for more than a year, and consequently the sales team there had received kudos from senior management, plus bonuses galore.

There were a lot of emotions surrounding this situation for Aimee. She reminded herself to answer Question 1 by acting as if she were a camera, taking snapshots of the circumstances.

The aspects of the situation she captured were:

It was highly probable that the Atlanta region was double- counting some results to appear to lead the country in sales.

The participant in Aimee's class who divulged the information to her was too frightened to do anything about the situation himself.

Aimee's manager would not pass the information up the food chain.

It was entirely up to her whether to address this situation.

Aimee's friends in other regions were not getting remunerated as they deserved because of the tactics of the Atlanta office.

Aimee felt she had a moral and ethical responsibility to do something, but was also concerned that if she did, it might hurt her career at the company.

If she did nothing, there would be no damage to her career; her boss had assured her of that.

Aimee was angry at the Atlanta regional manager for (probably) being an unethical leader.

As she answered this question, Aimee felt like she was between a rock and a hard place. Do nothing? Do something? She decided to calm her concerns and continue on with the Circle.

Aimee wrote down the following items as being negotiable in solving the conflict she faced:

Whether she did something about the situation was totally negotiable—the ball was in her court.

If she decided to take action, whom she approached was negotiable.

If she decided to do something, when she did it was negotiable.

Aimee knew very well that values in a corporation could be negotiable, depending on who the leader was and which polices were being reinforced in the company. To date with this company, she had seen most people walking their talk.

It wasn't a long list, as it seemed to Aimee that very few aspects were negotiable for her. This made her feel like she was tiptoeing through a minefield.

Aimee's list of nonnegotiable items was much longer.

Number one, Aimee's values weren't negotiable. She had been raised by wonderful parents, who taught her it was better to lose than to win by cheating.

Expecting her boss to address the situation was definitely out of the picture.

It was becoming more and more clear to Aimee that if she did nothing, she would be disappointed in herself.

The company's values were portrayed as nonnegotiable from, "Do the right thing!" to, "We are honest and ethical in everything we do." The plaque was on the wall for all to see.

Aimee's loyalty to her friends was nonnegotiable: she wanted to help them get what they were working so hard for, and deserved.

She didn't in any way want to implicate her manager. No one had to know that she had spoken to him at the outset.

Her loyalty to the company was nonnegotiable, as well—as long as she was being treated fairly and equitably. In the year and a half she had been an employee, this had been the case, so her loyalty was intact.

Aimee was 33 years old. She had been raised in a Midwestern town where there were fewer students in her high school than there were in her apartment building in New York City. She had grown up believing that with hard work, one could succeed. Within a week after arriving in New York to start work at her first corporate job, she had had her purse stolen on Broadway. Over the 11 years she had lived in the city, she had become less trusting and more skeptical.

In particularly difficult and/or sticky circumstances, this question asks us to search our life experiences for lessons we have learned and how they might be applied to the current situation. At times, what comes to our mind may seem remote and disconnected to the current dilemma, but I have learned that if I think of it, I'll find it has meaning and relevance. The lesson we learned is the key.

Two incidents came to Aimee's mind as she considered this question.

The first occurred when she was 10 years old. One of the students in her fifth grade class had been stealing from the other children. By accident, Aimee discovered who it was and told the teacher, quietly and in confidence. The culprit was caught and punished, and Aimee was rewarded by her teacher, her best friend, and her parents.

The second incident took place at a conference Aimee had attended three years earlier. Lily Ledbetter, who had filed a gender discrimination suit against Goodyear, spoke at the conference. In describing her travails, she impressed Aimee deeply. How someone could risk so much?

Recalling these incidents in response to Question 4 about learning from experience reinforced Aimee's anger at the Atlanta regional manager. It also clarified for her that she would likely have to do something. But what? She still couldn't answer that, as she moved on to Question 5.

Here's how Aimee answered this question:

She wished that she had not found out about the probable unethical behavior.

She was worried what the repercussions might be to her for taking action.

She was, nevertheless, bound to do something, for speaking out, addressing the situation, aligned with her values and the stated values of the corporation.

Answering Question 5 cemented her decision: she would make a game plan, and it would involve her speaking out about what might be a very serious unethical practice taking place at the Atlanta office.

Aimee knew the difference between being brave and being foolhardy, and kept this in the front of her mind as she considered her game plan. Together with two close friends, sitting in her living room one evening, she began to lay out the plan. They were very helpful and very supportive; they also raised issues that she had overlooked, which was extremely beneficial.

The plan they developed contained these actions:

Contact George, the VP of sales, and ask for an appointment, at which time Aimee would to fill him in on information that might be helpful to the sales force.

She would mention the meeting in her weekly status report to her boss after she met with George, thereby in no way implicating him—that he had chosen not to address the situation.

At the meeting with George, the sales VP, she would assert that she wanted the discussion to be kept in confidence.

She would tell George what she had discovered in Atlanta, but not divulge the name of the individual who told her.

She would be clear that she had no hard evidence, but that she thought it viable enough to at least warrant an investigation by George.

Aimee would ask George to keep her out of the situation—that is, she wished to remain anonymous.

She decided she would not tell anyone else at work what she was intending to do.

The next morning, Aimee planned to call the sales VP's office and get on his calendar. She hoped she would not have to wait too long until they could meet.

All Aimee could really focus on at this point was what personal transformation might result from her decision to move ahead in confronting the situation. Anything beyond that was out of her control.

This is important to keep in mind when we respond to this question: The only person we can control is ourselves. In dealing with others, we can wonder about the potential transformation our actions might bring to us; we cannot expect others will change. In Aimee's situation, she could hope that practices in the Atlanta regional office would change (if the allegations were proven to be true), but that wasn't her response to this question.

Question 7 asks us to look at how we will change, or be changed, by our decision—perhaps in our confidence, how we act toward others, or how we feel about and perceive ourselves.

In pondering this question, then, here's what Aimee came up with:

In a competitive world, which seemed to produce mistrust of others, she would show herself to be an ethical, trustworthy person.

She believed she would feel proud and confident in a way she hadn't felt in quite a while.

She hoped she might help right a wrong at the company, even as she recognized that was unlikely to happen.

Her game plan seemed to reaffirm the Aimee she remembered from fifth grade: brave and willing to do what was right for the greater benefit of all. Now, she thought, she was beginning to sound like a girl scout, so she was quick to remind herself that this was business, not elementary school—and who knew what else might happen?

Aimee's answer to this question was split: On the one hand, her game plan would ultimately have a positive effect on her perception of herself as an honest professional, loyal friend, and a woman who tries to do the right thing. On the other hand, she had no idea what moving forward might do to her career; would she become a pariah, an outcast, and eventually have to leave the company? She didn't think so, but she wasn't 100 percent sure.

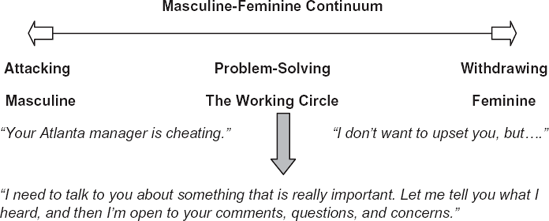

Let's examine the Masculine-Feminine Continuum to see the contrast in approaches for Aimee with George, the sales VP.

Here's how this challenge played out:

When Aimee got in to see George, and after some small talk, she told him she needed to speak to him in confidence, as per her game plan. After he agreed, she said to him: "I heard some disturbing information when I was in Atlanta. I am not sure it is true, but I decided to let you know, just in case it is. I know you will do what you think is best and I request that I remain anonymous. I will not speak of this to anyone else. I heard that the Atlanta regional manager is double-counting sales results so that his region will lead the country."

Their conversation continued for another 15 minutes, after which Aimee left his office, feeling both very nervous and very relieved. Three months later, the Atlanta regional manager was transferred to another position in the company. Three months after that, he left the company. George never said anything to Aimee again, but he did give her a handshake at the next national sales meeting, and a very big smile. Aimee was proud of herself and the company she worked for.