It isn't comfortable watching other people argue in front of you. Maybe you want one person to prevail, maybe not. You certainly don't want to get in the middle: the one in the middle gets the bullet hole! Earlier in my life, I tried to get in the middle, and was amazed that both sides ended up angry at me! After a number of unexpected bruises, I stopped going there.

Mediating is not putting yourself in the middle; it is facilitating discussion and problem solving. Mediators hold a position of neutrality—more accurately, they approximate neutrality, since it is almost impossible to be totally neutral. The best we can expect to do, as mediators, is keep our biases at bay and interfere as little as possible in the reconciliation process.

When two people at work are at war—or worse, when there are warring factions—the organization suffers, as do individuals. Information doesn't flow the way it should, and, as we all know, information is key to any organization's success. I believe that another reason, beyond greed that so many organizations go astray is due to all of the internal wars that go on. Often at such companies, the leaders don't try to stop the conflict, much less teach the combatants to problem solve; they either turn a blind eye or support one side over the other. In this way, they deliver a message to the troops that it's acceptable to argue, but just make sure you are on the winning side. Or, put another way, disagreements are okay, as long as you are right. And we know that being right usually can be determined only in hindsight.

Working around two people (or two teams) that are at war can be awkward, personally as well as professionally. The discomfort grows more extreme when the conflict hampers your ability to do your job. Also, as conflict heats up, either side might look to you to become its ally.

Remaining neutral is definitely a skill you can develop. People who are viewed as neutral often have a perceived strength, as they can communicate with either side of the conflict with relative ease. Obviously, once you take a side, you risk alienating the opposition.

Taking a side on an issue that you feel strongly about one way or the other is an experience we have all had. You agree with one side and so align yourself with others who feel the same way. What becomes critical is how you and your allies participate in the disagreement. Acting as a person with integrity and values will take you a long way, especially if your side does not prevail. Keep in mind, you will have to work with these adversaries again, once the issue has been resolved. If your side is victorious, those you disagreed with will be more likely to be cooperative in the future if you competed with integrity and with respect for all concerned. This is not naïve, I assure you. Over the long term, it is those professionals who have integrity and an intense drive that others respect.

I began working with one company when it was two years into a merger. When employees referred to "we," they meant the company they used to work for, not the merged entity. Alliances were based on which company you came from, thereby inhibiting a collaborative incorporation of the two firms, which had been successful as individual entities. When I asked an employee how a process was carried out, for example, I was told, "This is the way we did it, and it is much better than the way they do it."

On the upside, management did institute training classes and distributed newsletters in an effort to promote a more cooperative working environment, in an attempt to make the merger successful. On the downside, performance reviews and compensation practices did not match up; they did not reward collaboration, but individual effort. As a result, astute employees and managers who knew the value of collaboration built alliances with the other side. I observed that the ongoing conflict slowed down the progress of the merger, and cost the combined company a great deal in lost productivity. Leadership, with all good intentions, took the stance of a parent: "Now play well, all of you!"

I had another experience relating to this challenge, one in which I got caught in the crossfire. When I worked in human resources, my team was charged with supporting multiple business units. At one company, I worked for two senior managers who hated each other—I do mean hate! Clearly, I had to remain neutral, as I reported to both of them. One of the men complained about the other; the second man never trusted me because he thought I might pass along confidential information to his foe. I was caught in the middle, and so was my staff. Still, I was careful never to speak critically of either man to anyone.

The conflict between these two managers prevented, among other things, the amicable transfer of employees from one unit to the other, successful cross-selling and adequate implementation of companywide initiatives. After a number of months in the job, I offered to sit down with them both, in an effort to get them to address some of the business (not personality!) issues coming between them.

Business was being negatively affected for both of them in part due to their disagreements, so they agreed. We met on neutral territory, and covered basic business and HR issues. We came up with a plan, and my team and I ensured impartial support for its success. Subsequently, although there was a lot of slipping and sliding (senior management tacitly encouraged the conflict), things did improve. They improved because each man was highly motivated to succeed, and my mediation highlighted the need for them to collaborate on some issues, and this gave both of them a better chance to meet their objectives.

Throughout this book, I hope you have noticed that courage is one of the hallmarks of the stories I share with you. I feel strongly about being courageous—prudently courageous. I have known many people who have exhibited great courage in dealing effectively with conflict at work. This challenge, "Mediate or take a side?" has an underlying question: "What do you have the courage to do when other people around you are in conflict?" Taking action does not necessarily imply having courage. Wisdom is a far stronger indicator of courage, and that means knowing when to act and when not to.

Recognizing there is nothing you can do to alleviate a situation takes wisdom and courage. Taking sides out of expediency demonstrates pragmatism, which is often necessary to keep one's job—and one's sanity. Deciding to mediate likewise takes courage, and doing it effectively takes wisdom. We all need to maintain our self-respect and integrity in the face of conflict.

Enough said on these points. On with the story relating to this tricky challenge.

Brian was a sales representative for an insurance broker. He had been selling property and casualty insurance for four years, and enjoyed the work. Recently, the brokerage had not been doing well, and the agency had to let a number of salespeople go. After the layoffs, Brian was required to sell property/casualty and health insurance. That meant he now had two managers, one for each product line. Bill (property and casualty) had been Brian's manager for a year; Erin (health) was his new boss. They were very competitive with each other.

The prospects Brian needed to call on were different for each product line. Leadership in the company assumed (as leadership often does) that the new arrangements would work out just fine; they expected everyone to understand these were trying times.

Under stress, people tend to become either heroes or villains. Stress brings out the best or the worst in us. In this case, it did not bring out the best in Bill and Erin, much to Brian's chagrin.

When Bill gave Brian his sales goals after the new arrangement went into effect, he made it clear that he resented that Brian would now be working only 50 percent of the time for him. He had modified the goals slightly to reflect that. Brian was assured that he could accomplish these goals, as they were more modest than they had been in the past. As already noted, Bill had been Brian's manager for the last year, and they got along well. Bill was a regular kind of guy; he worked hard, had a family, coached Little League, and basically worked a nine-to-five day, most days. Bill was not a star at the firm, but he was a steady producer. In the past, Brian would have preferred that Bill be more aggressive with sales, but Bill consistently took the middle-of-the-road approach, preferring safety to spectacular results. His sales were always good.

Erin, in contrast to Bill, had big plans for herself. She did not respect Bill; he was milquetoast to her. She wanted to rise up in management, and with Brian now reporting to her, she believed she could increase her numbers, on the back of his efforts. Erin was willing to do what it took to increase sales, and when she sat down with Brian, she told him so.

"Go out there and kick butt! Now is the time to sell group insurance," she said, taking into account what had been happening in Washington in regard to health care. She believed that now was the time to sell the affordable products the agency offered.

Erin also told Brian that if he exceeded the goals set for him, she would ensure that he would be promoted to a management position within a year. That promotion would give Brian more responsibility, as well as more money, which he certainly needed, with a baby on the way. But then she added a comment that changed the tenor of the conversation.

"Don't tell Bill that I spoke to you about the possible promotion," Erin confided to Brian. "He's not going anywhere, and he's lucky he wasn't included in the layoffs." At this point, Brian became uncomfortable with the conversation. He liked Bill and knew how much he needed his job. Moreover, the office gossip about Erin was that though the owners of the agency liked her, she was regarded as a "dragon lady"; she took no prisoners. Brian began to wonder how this split in his responsibilities was going to work out.

Over the next three months, the tension mounted. Erin and Bill gave Brian conflicting directions, and they began to criticize each other in front of Brian, which caused him even greater discomfort. Adding to Brian's stress level was that both Bill and Erin wanted more and more of his time and effort. He started to feel as if he were being stretched in two directions, and that he could easily fail both managers as their demands and expectations of him grew.

As the conflict intensified, both Bill and Erin would ask Brian questions about the other. Each also leaned on Brian to not move as quickly for the other. If, for example, Brian had a good week with one product line, the opposing manager would chide him for not working hard enough for him or her. The environment grew steadily more tense, at the same time the agency's results were not improving significantly, raising fears of more layoffs.

Brian now believed that the managers wanted more of him not just to improve the results of their divisions, but to outdo the other. He also realized that to meet each manager's expectations, he would probably have to work a 70-hour week! He was becoming more and more concerned about his future; how could he possibly succeed in such a contentious environment? If he fell short, would Erin blame him and make him the fall guy? Was Bill strong enough to keep his job with the agency? How would that affect Brian's prospects?

Brian tried to explain to Bill and Erin, in separate conversations, that their conflict was making it harder for him to succeed, for them and for himself. Bill was compassionate, but insisted that property and casualty was where Brian needed to direct his focus. For her part, Erin continued to remind Brian that if he wanted to succeed, he would have to ride on her coattails.

Brian had to figure out what he could do—if anything. He had approached Tom, the senior manager, one day, very casually, and hinted at the conflict between his two managers. Tom merely laughed and said, "May the best man, or woman, win!" He was not going to get any help there, thought Brian. Tom was flaming the fires of the conflict to increase results; everybody knew he loved a good fight.

The questions before Brian were: "Should I take sides? Should I do nothing? Should I attempt to mediate?"

Brian and I went to The Working Circle.

Here's how Brian answered Question 1:

He wanted to succeed, and one day move into management.

Brian liked Bill, but was wary of Erin.

Brian did not want to get in between Bill and Erin's conflict.

Senior management was encouraging the conflict between Bill and Erin, hoping it would increase revenue.

The conflict and tension was growing worse between Bill and Erin, and for Brian, too.

If things continued the way they were going, Brian's ability to succeed would be hampered, as each manager wanted more and more of him.

Brian liked Bill better than Erin, but Erin might be more successful at the agency in the long term.

This was a messy situation at best, and at worst could cost him his job.

He wasn't enjoying his job anymore.

This was not the best time to look for another job, although that might become a possibility in the future (when the economy improved and after the baby was born).

Brian felt stuck. He was working very hard, yet wasn't producing the results he would have liked in either product line.

Brian believed he could work for either Erin or Bill, but working for both of them was becoming intolerable.

Brian listed these items as being negotiable in resolving the conflict he was facing:

Brian was willing to sell either property and casualty or health insurance—he liked both.

He had a good relationship with Bill—a general level of trust existed between the two men—and so he felt he had some leeway in what he said to him.

An offsite meeting, scheduled for a month out, might offer a good opportunity for Brian to sit down with both his managers, if he decided to go forward.

Brian didn't necessarily see himself working at this agency long term; certainly, if things didn't improve, he was open to going elsewhere when it became feasible for him.

As Brian listed his negotiable items, he started to feel less trapped. Whether he took action or not, he knew that, eventually, the economy would improve, his baby would be born, and he could go elsewhere, if need be. With this more positive outlook, he continued around the Circle.

Most people working the Circle have an easier time figuring out what is nonnegotiable than what is negotiable. Brian was no exception:

He was unwilling to compromise his values for either Bill or Erin.

Although Brian liked Bill more than he did Erin, he would not take sides. That was far too dangerous in this uncertain environment.

Brian wanted to remain neutral; he preferred that position and felt it to be a more professional stance to take.

At this point, the question regarding the situation changed for Brian. He had begun by asking: "Should I take sides? Should I do nothing? Should I attempt to mediate?" It was clear now to him that he would not, and should not, take sides. That was not an option, for he could not be sure which way things would wind up at the agency.

Brian continued answering what was nonnegotiable for him.

In no way did he want to jeopardize his career in insurance.

He did not intend to leave the agency until after his baby was born. Changing benefit plans midway in his wife's pregnancy was not advisable.

He was determined to succeed; failure was not an option.

Reviewing his responses to this question, Brian became bolder still. Somehow, knowing how and where he would put his foot down made him feel more in charge, and less trapped in the conflict between Bill and Erin. He also became clearer that his preference for one manager over the other really had nothing to do with addressing the situation; he was well aware that alliances shifted all too easily in an uncertain environment.

As soon as Brian asked himself this question, a memory from his childhood popped into his mind. He was the middle child in his family, and his older sister and younger brother were always fighting. When they were kids, Brian's siblings used him as bait to incite one another. Consequently, Brian often felt angry and taken advantage of—caught in the middle. He realized how similar the current situation was.

What had Brian learned from his childhood experience? His parents, like senior management, were of very little help to him. They were not home a lot; both worked to provide for the family. Brian complained to his siblings, but they were so embroiled in their own conflict that they weren't really aware of the effect it was having on their brother. Brian felt helpless. His solution was to avoid his siblings as much as he could, but this, too, left him feeling angry, helpless, and lonely.

The lesson Brian learned was that being helpless left him feeling empty, and caused him to withdraw. As an adult, this was definitely not what he wanted to carry over into his professional life.

Answering Question 4 raises another important point, which many of my clients prefer to run through or avoid totally, relating to hindsight. We often learn from the consequences of our past decisions, whether or not they worked the way we wanted. (Note that I deliberately avoid using the word "right." My point here is about where the consequences of our decisions have taken us, not whether we were "right" or "wrong." If we could minimize such binary-type thinking, we all would become better conflict resolvers.)

Hindsight gives us insight, knowledge, as well as the ability to correct our courses. Asking "What did I learn from previous experiences?" opens us up to learning and closes the door to blaming. Blaming does not encourage learning; rather, it encourages avoidance and, for some, dishonesty. When was the last time you attended a meeting at work and the past was used as a foundation for learning and discussion?

Before he moved on to the next question, Brian remembered another circumstance that he thought might shed light on his current situation. When he was working at his first job out of college, two peers who were in conflict asked him to step in and mediate between them. They trusted Brian, and preferred talking to him over going to management. Although Brian felt he had no skills as a mediator, he agreed to try to help. Over a few beers, and with Brian's help, the two peers came to a resolution. They were very grateful to Brian, and thanked him over and over. From Brian's point of view at the time, all he did was ask questions and let them talk.

Now, remembering this event, Brian thought that he might be able to facilitate a conversation between Bill and Erin—if it could take place in a relaxed setting, such as the upcoming retreat the company was planning. And, as he responded to each question in The Working Circle, he was growing bolder about taking action.

Looking into past experiences was helping Brian expand his perspective on the present situation. His confidence was growing that this very sticky situation might be resolved, and not necessitate his looking for a new job.

That's another valuable aspect of The Working Circle: it offers hope for finding solutions to difficult problems. I've seen client after client begin with little hope they could arrive at a satisfactory or peaceful resolution to their problem. Then, as they work through the Circle, I see their hope begin to resurface. In my experience over 14-plus years using the Circle, I've discovered that for most situations, (excluding dangerous situations or those involving rigid or disturbed individuals), this collaborative problem-solving approach works. The process, along with the introduction of a collaborative, non-accusatory language, makes resolution of even the most conflicted situation possible. Have faith!

At first, Brian felt a little silly relating past experiences to the present. But he came to understand that those memories were providing confirmation of his abilities. With renewed confidence, he moved on to the next question.

When Brian arrived at this question, he stopped to ponder before beginning to answer it. People didn't ask "feeling" questions at work, and, truth be told, he generally preferred not to reveal how he felt. So he found himself resisting answering this question.

To help him through this impasse, I asked him a few peripheral questions.

"How do you feel now versus how you felt when you started with The Working Circle?"

"More confident and a little more relaxed", he responded. "At the same time, I am on edge about determining what I am going to do."

His response was completely understandable. One can feel better about something while still being anxious about what to do.

To prompt him once more, I asked, "If you review your answers to the first four questions, how do you feel about what you have said so far?"

Brian took a moment to go through his notes (which he had been taking as we went along, an activity I highly recommend). As a result, he went back to his nonnegotiable list and added another item. (For convenience, I included the item in the list of responses to Question 3.)

One of the purposes of this question is to allow us to take a moment before we jump into planning. Brian was a man of action; that was one of the traits that made him a superb salesman. But in resolving conflict, we need to move with prudence; we need to be thoughtful before we take action. Answering Question 5 motivates us to review our responses. In this way, we can go back and add and/or delete responses as we see fit to any or all of the preceding questions.

The more thorough we are in addressing Questions 1 through 5 before we begin to develop our game plan, the more comprehensive the plan will be. That then increases our chance of facilitating a win!

One additional point here, before we move on: Brian, in reviewing how he felt about the situation, also reflected on the behavior of Bill and Erin. "You know, I'm annoyed at both of them for causing this situation. They really are acting worse than my kids," he said.

We both laughed.

After Brian made that comment, he paused again, then smiled. "You know, I actually feel good about what I have said so far," he said. "I'm ready to make a plan."

Thanks to growing confidence in himself, Brian decided to attempt mediation. He had talked it over with his wife, too, who expressed pride in his courage, and agreed that he was right to attempt mediation.

What follows is Brian's plan:

Make a list of his sales prospects and estimate how much he thinks he can sell in the next six months.

Chart a breakdown of how much of his time he spends on prospecting, sales, and service. Give to Bill and Erin for the purpose of demonstrating how unrealistic their collective demands are becoming.

Scope out a room at the site of the agency retreat where the three of them can meet in private.

A week before the retreat, tell Erin and Bill that he would like to sit down with them together to discuss the very difficult situation he is facing. Stress the importance of the meeting, and that his goal is to make it a problem-solving interaction, not a confrontation.

Take The Working Circle diagram with him to the discussion. This will be helpful to him in his role as the mediator. It should also be helpful for Bill and Erin, as they will be able to recognize it as a nonthreatening process for guiding their conversation.

Take notes during the conversation, to ensure that all three of them will have a record of what was said, to help them adhere to the agreements they make.

Bring a small gift for each of the managers, as a thank you for participating—something lighthearted, to make them all smile.

Brian summarized his objective for the meeting in this way: Increase sales results through a more efficient use of time and reduction of conflict. This objective was not intended to be interpreted either as blaming or complaining; Brian simply wanted to do the best for all of them, and they needed to understand that their conflict was inhibiting that goal.

Brian reviewed his plan, and then his answers to all of the previous questions. "I'm ready," he said to me.

As always, Brian was ready for action, so I had to remind him that he had two more questions to answer.

"If you complete your plan, and mediate to meet your objective, what changes would you expect to see in the situation?" I asked Brian.

"Besides seeing them both [Erin and Bill] grow up and stop torturing me?" Brian asked with a smile, before answering more seriously, "I'd like to see them stop badmouthing each other to me, and most of all I'd like to be able to succeed with realistic goals and with realistic timeframes."

Once again I had to put the reins on Brian's desire to spring into action immediately. To do that, I asked him to enumerate the transformations that he thought might come as a result of his actions. Here is what he said:

Finally, to rubber stamp the discussion, I asked Brian Question 8.

Brian paused for a moment. "These changes will be positive only if the mediation doesn't backfire on me."

I understood his concern, but I also had complete confidence in Brian's ability to mediate with a good sense of what could and could not be accomplished. We completed the Circle and Brian began to put his plan into action.

To show how Brian worked the mediation, I will give you a summary of what transpired.

Following his plan, Brian asked Bill and Erin to meet with him at the retreat. He arranged for their talk to take place where they could be assured of privacy. He told his two managers that he wanted to talk to them about his performance, and working with the two of them. He was very careful not to criticize either of them or hint that they were doing anything wrong.

Bill and Erin agreed—although with some apprehension—to the meeting.

At the agreed-upon time and place, they all sat down—after some uneasy joking. Brian knew that his first words were critical.

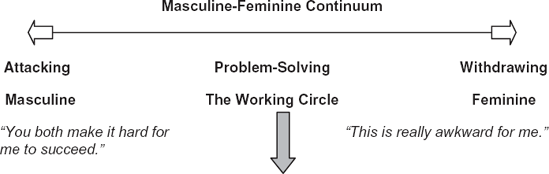

So, before we go further into the discussion, let's first look at the Masculine-Feminine Continuum to see the contrast of possibilities for Brian at this juncture.

Brian started the dialogue by taking a problem-solving approach, thereby setting the tone for collaboration:

"I wanted us to have this discussion because I want to succeed in meeting the goals set by each of you for me. Unfortunately, it is rather difficult due to the conflict that is going on between the two of you. I thought we could take a little time to clear the air, because if we don't, I fear my success is in jeopardy."

After a few comments from Bill and Erin—such as: "Of course I want you to succeed!" "I didn't know it was hard for you"—Brian introduced The Working Circle. He showed them the diagram and explained it was a useful tool they could use to help them discuss, without arguing. He asked for their agreement. Bill and Erin assented.

Brian stated that his goal for their conversation was twofold: to enable him to succeed, and to minimize the tension he was working under because of their conflict. (Note that he did not accuse either Bill or Erin; he spoke only for himself. That tactic enables collaborative discussion and problem-solving behavior.)

The three of them then walked through the questions of the Circle. Here is a summary of their findings:

Bill and Erin didn't like each other, but they both liked Brian.

They wanted Brian to succeed.

Times were tough, and Brian's dual assignment should last only until things got better—the economy improved.

Brian could divide his time and efforts as he saw fit.

Bill and Erin could determine how to handle their disagreements.

Erin and Bill would stop making negative comments about each other in Brian's presence. (This was a difficult one; both were on the defensive. Brian emphasized that the comments they had made weren't harsh, but they were unproductive.)

Brian's failure was not an option for any of them.

Unproductive conversation was not permissible!

Results at the company had to improve.

Difficult times pass.

Managers must do whatever they can to help their staff members succeed.

Personal conflicts should be left out of business discussions.

Brian was ecstatic when they got to Question 6, the game plan. Everyone agreed on the following:

They would schedule progress meetings for the three of them, at which time Brian would give Bill and Erin the same data at the same time.

Their meetings would also minimize the complaining that had been going on, and therefore would maximize the chances of Brian's success.

The managers agreed not to be critical of each other in front of Brian.

We all will have a greater chance for to succeed.

Brian will have a more manageable schedule.

The tension between Bill and Erin will, perhaps, ease.

One final note: During their discussion, Bill and Erin had touched lightly on their existing conflict, although Brian had not made that the primary issue. Now they acknowledged that whatever was going on between the two of them would probably continue, but they also agreed that Brian should not be caught in the middle of it any longer.

After the meeting, both Bill and Erin complimented Brian individually.

"That took courage," Bill said to Brian when they were alone.

Later, Erin told Brian, "My, my, you peacemaker! I like what you did!"