Chapter 4

The Villain

“I do empathise with people who are driven by dreadful impulses. I think to be driven to want to kill must be such a terrible burden. I try, and I think I succeed, in making my readers feel sorry for my psychopaths, because I do.”

—Ruth Rendell

As any mystery reader knows, today’s villain is no Snidely Whiplash, standing in broad daylight, twirling his moustache and sneering. Any character who looks that nefarious will almost certainly turn out to be innocent.

Readers are delighted when the bad guy was hiding in plain sight, an innocuous-looking character who cleverly conceals his true self, luring trusting victims and then snaring them in a death trap. But “the butler did it” won’t wash in a modern mystery. Minor characters who are part of the wallpaper for the first twenty-eight chapters can’t be promoted to villain status at the end just to surprise the reader. And you can’t give a character a personality transplant in the final chapter. Disbelief will trump surprise unless you’ve left subtle clues along the way.

PLANNING AHEAD

Some writers know from the get-go which character is guilty. They start with the completed puzzle and work backwards, shaping the story pieces and fitting them together. Others happily write without knowing whodunit until the scene when the villain is unmasked. Then they rewrite, cleaning up the trail of red herrings and establishing subtle clues that make the solution work.

Do you need to know the bad guy’s identity before you start writing? I do. I always think I know, but about half the time I turn out to be wrong. My friend and fellow author, Hank Phillippi Ryan, says she never knows the identity of the villain until she writes it. She’s as surprised as her readers.

CREATING A VILLAIN WORTH PURSUING

You can’t just throw all your suspects’ names into a bowl and pick one to be your villain. For your novel to work, the villain must be special. Your sleuth deserves a worthy adversary—a smart, wily, dangerous creature who tests your protagonist’s courage and detective prowess. Stupid, bumbling characters are good for comic relief, but they make lousy villains. The smarter and more invincible the villain, the harder your protagonist must work to find his vulnerability and the greater the achievement in bringing him to justice.

Must the villain be loathsome? Not at all. He can be chilling but charming, like Hannibal Lecter. She can be shrewd, gorgeous, and vulnerable, like Brigid O’Shaughnessy in The Maltese Falcon. (Who among us isn’t a little bit conflicted when Sam Spade lets the police cuff her?) It’s better when the reader can muster a little empathy for a complex, realistic bad guy who feels his crimes are justified.

So, in planning, try to wrap your arms around why your villain does what he does. What motivates him to kill? Consider the standard motives like greed, jealousy, or hatred. Then go a step further. Get inside your villain’s head and see the crime from his perspective. To law enforcement, it might look like a murder motivated by greed. To the perpetrator, it might look like a means to a noble, even heroic, end.

Here’s how a villain might justify a crime:

- righting a prior wrong

- revenge (the victim deserved to die)

- vigilante justice (the criminal justice system didn’t work)

- protecting a loved one

- restoring order to the world

- God’s will

Finally, think about what happened to make the villain the way he is. Was he born bad? Did he sour as a result of a past experience? If your villain bears a grudge against society, why? If she can’t tolerate being jilted or ignored or teased or shortchanged, why? You need to know your villain’s backstory, even if you never share it with your reader.

By understanding how the villain justifies the crime to himself, and by knowing the formative events in his life, you give yourself the material you need to get past a black-hatted caricature and to paint your villain in shades of gray.

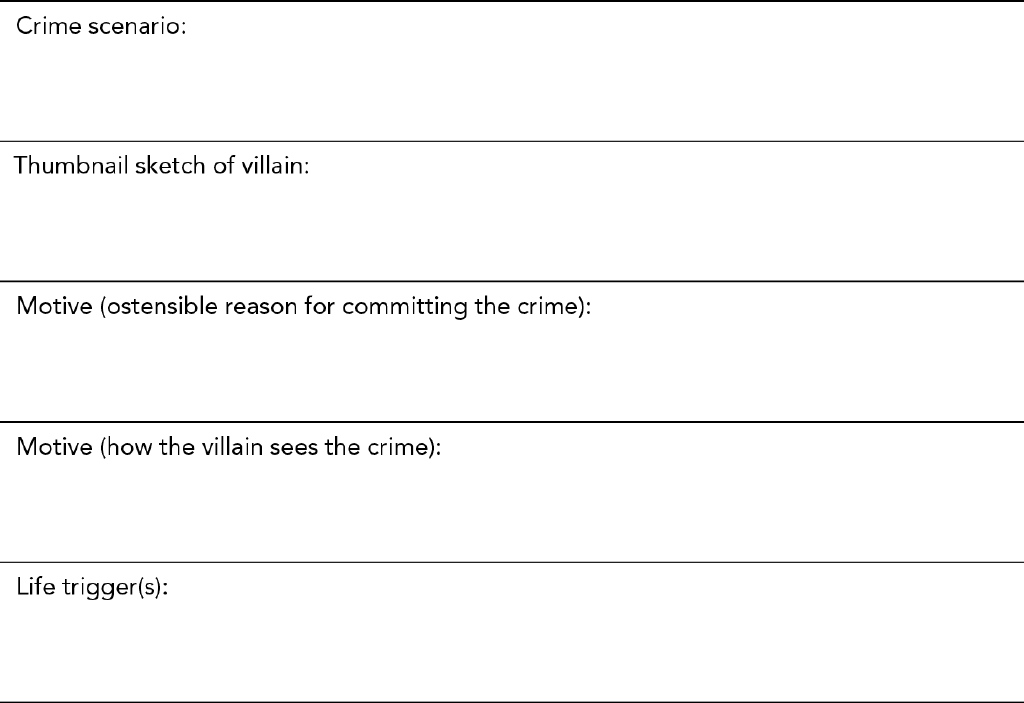

Here’s an example of the information you need to decide about your villain before you write.

| Crime Scenario | Who gets hurt, how, and where | Lorinda Lewis, a thirty-year-old bank teller, is carjacked, thrown from the car, and killed. |

|---|---|---|

| Thumbnail Sketch of Villain | Basic information: name, age, job, physical description, family, background | Drew MacNee, bank manager, boyishly handsome; fiftyish; father of two teenage girls; married to the mousey but wealthy Melinda for twenty-five years; lifts weights and runs thirty miles a week; grew up the youngest and the only son with three older sisters in an affluent household and always got what he wanted. |

| Motive | Ostensible reason for committing the murder | To keep Lorinda from revealing his many affairs with young, attractive bank tellers (including Lorinda). |

| Motive | How the villain sees the crime | “Lorinda, that vengeful bitch, couldn’t stand it when I dumped her; now she’s out to destroy everything I’ve worked so hard for. I’ve got to stop her and protect my family.” |

| Life Trigger(s) | Past experience that might explain why the villain commits this crime | When Drew was captain of his high school football team, he and his buddies raped a girl and were protected from prosecution by the coach and town officials. |

Now You Try: Spending Time in Your Villain’s Head (Worksheet 4.1)

Think about the villain in your mystery novel. Jot down your ideas.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

MAKING THE CRIME FIT THE VILLAIN

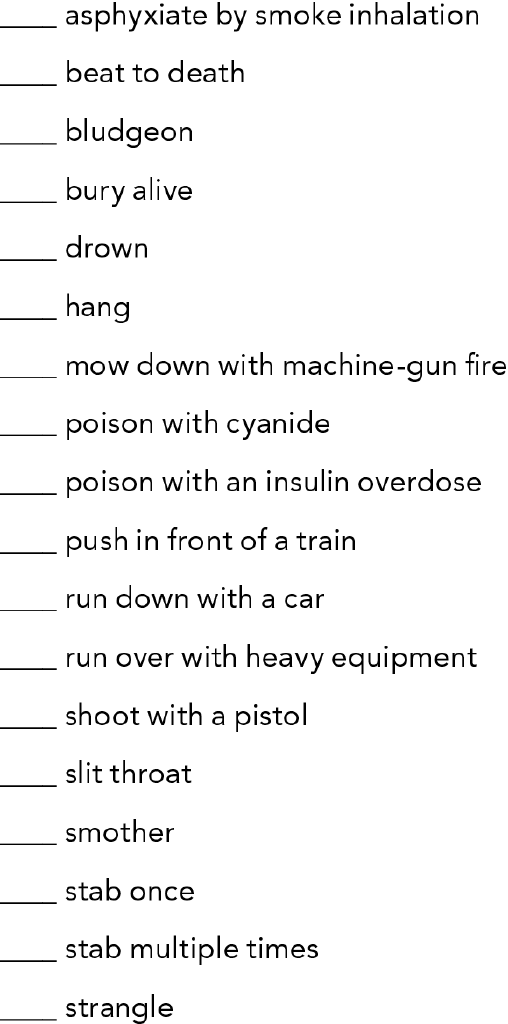

There are many ways to kill off a victim. You can have him shot, stabbed, strangled, poisoned, or pushed off a cliff. You can have her run over by a car or bashed in the head with a fireplace poker. But murder is not a random event. The first issue to consider is the following: Would this particular villain have the expertise, capabilities, and disposition to commit this particular crime?

Here’s an example: Suppose I’m writing about a surgeon who, up to page 302, has been the soul of buttoned-down respectability. Suddenly, on page 303, he leaps from a hospital laundry bin brandishing a machine-gun and mows down his professional rival, another doctor who’s competing with him for the open hospital director position. Never mind that up to that point in the novel, this guy has done nothing more than attend board meetings, get drunk and obnoxious at a cocktail party, and perform heart surgery. Now, suddenly, he’s the Terminator? The behavior doesn’t fit the character. If he stabbed, poisoned, or pushed his rival off the hospital roof, the reader might swallow it. The author might get away (barely) with the shooting if hints were dropped earlier that this surgeon once served in military Special Forces.

Choose a modus operandi that your villain (and your suspects) might plausibly adopt, and establish that your villain has the capability and expertise required. A murder by strangling, stabbing, or beating is more plausible if your villain is strong and has a history of physical violence. If your villain plants an electronically activated, plastic explosive device, be prepared to establish how he learned to make a sophisticated bomb and how he got access to the components. If a woman shoots her husband with a .45 automatic, be prepared to show how she learned to use firearms and that she’s strong enough to handle the recoil of a .45.

The second issue to consider: Is the rage factor appropriate?

The more extreme the violence, the more likely the crime was motivated by hatred and rage. A robber shoots a victim once; an enraged husband pumps bullets into the man who raped his wife. A villain may administer a quick-working, deadly poison to a victim he wants out of the way, but a villain who hates his victim might pick a poison that’s slow and painful, and then hang around to watch the victim die.

Adjust the violence quotient to match the amount of rage your villain has toward his victim.

Now You Try: Make the Crime Fit the Villain (Worksheet 4.2)

How would your villain kill his victim? Consider your villain’s motive, strength, and expertise. Consider the rage factor. Check the methods that could fit.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

On Your Own: The Villain

- Reread a favorite mystery novel, or read Scott Turow’s Presumed Innocent or Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None (Ten Little Indians). Pay special attention to the villain. Think about how the author creates a bad guy who is somewhat sympathetic and three-dimensional, and how the villain rationalizes the crime.

- Brainstorm your villain and jot down your ideas: family background, physical appearance, education, formative events, and so on.

- Pick a plausible modus operandi for your villain, taking into account your villain’s capabilities, expertise, and relationship to the victim.

Complete the Villain section of the blueprint at the end of Part I.