Chapter 6

The Supporting Cast

“Without Goodwin’s badgering, Wolfe would surely starve, collapse under the weight of his own sloth …”

—Loren D. Estleman, from the introduction to the 1992 Bantam paperback edition of Fer-de-Lance by Rex Stout

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle gave Sherlock Holmes a full panoply of supporting characters. There was Dr. Watson, the quintessential sidekick, to provide Holmes with a sounding board; Scottish landlady Mrs. Hudson to cook and clean and fuss over Holmes; Scotland Yard detective Inspector Lestrade to provide a foil for Holmes’s intuitive brilliance, as well as access to official investigations; the Baker Street Irregulars to sneak around where Holmes can’t and ferret out information; and Mycroft Holmes, his politically powerful older brother, to provide financial and strategic support.

Likewise, your cast of supporting characters should reflect what your protagonist needs. For instance, an amateur sleuth needs a friend or relative with access to inside information: a police officer, private investigator, or reporter fits the bill. A character who is arrogant and full of himself needs a character to keep him from taking himself too seriously, maybe an acerbic co-worker or his mother. You might want to show a hard-boiled police detective’s softer side by giving him kids or a pregnant wife.

THE SIDEKICK

The most important supporting character is the sidekick. Many mystery protagonists have one. Rex Stout’s obese, lazy, brilliant Nero Wolfe has Archie Goodwin—a slim wisecracking ladies’ man. Robert B. Parker’s literate, poetry-quoting Spenser has black, street-smart, tough-talking Hawk. Harlan Coben’s former basketball star turned sports agent, Myron Bolitar, has a rich, blond, preppy friend, Windsor Horne Lockwood III. Tess Gerritsen’s medical examiner, Dr. Maura Isles, plays a cool, self-contained, and logical counterpoint to Detective Rizzoli’s hot-tempered passionate impulsivity (they’re each other’s sidekicks).

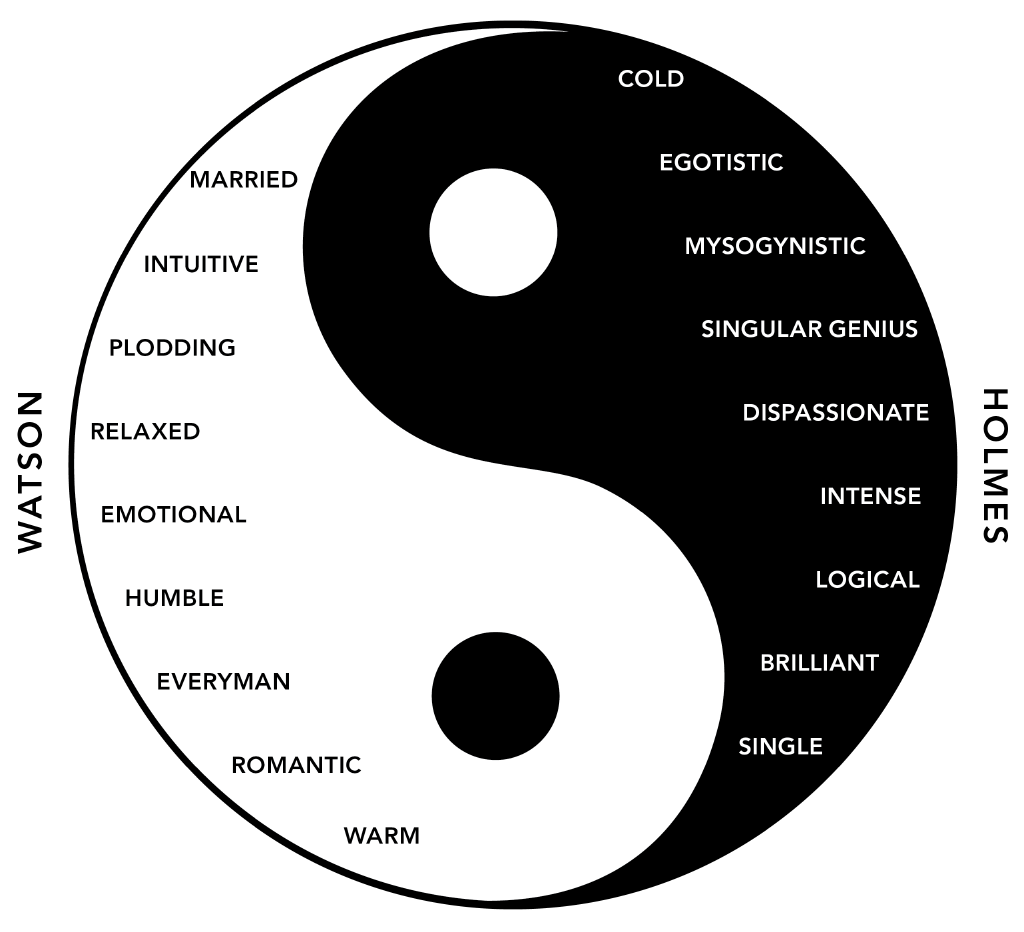

Dr. Watson, a married medical doctor, romantic and sentimental, says of Holmes in “A Scandal in Bohemia”: “All emotions … were abhorrent to his cold, precise, but admirably balanced mind. He was, I take it, the most perfect reasoning and observing mind that the world has ever seen.”

See a pattern? It’s the old “opposites attract” setup. Mystery protagonists and their sidekicks are a study in contrasts. Sidekicks are the yin to the protagonists’ yang. The contrast puts the protagonist’s characteristics into relief.

So the place to start in creating a sidekick is the profile you developed of your sleuth in chapter two. Think about how the sidekick’s traits can mirror those of the protagonist.

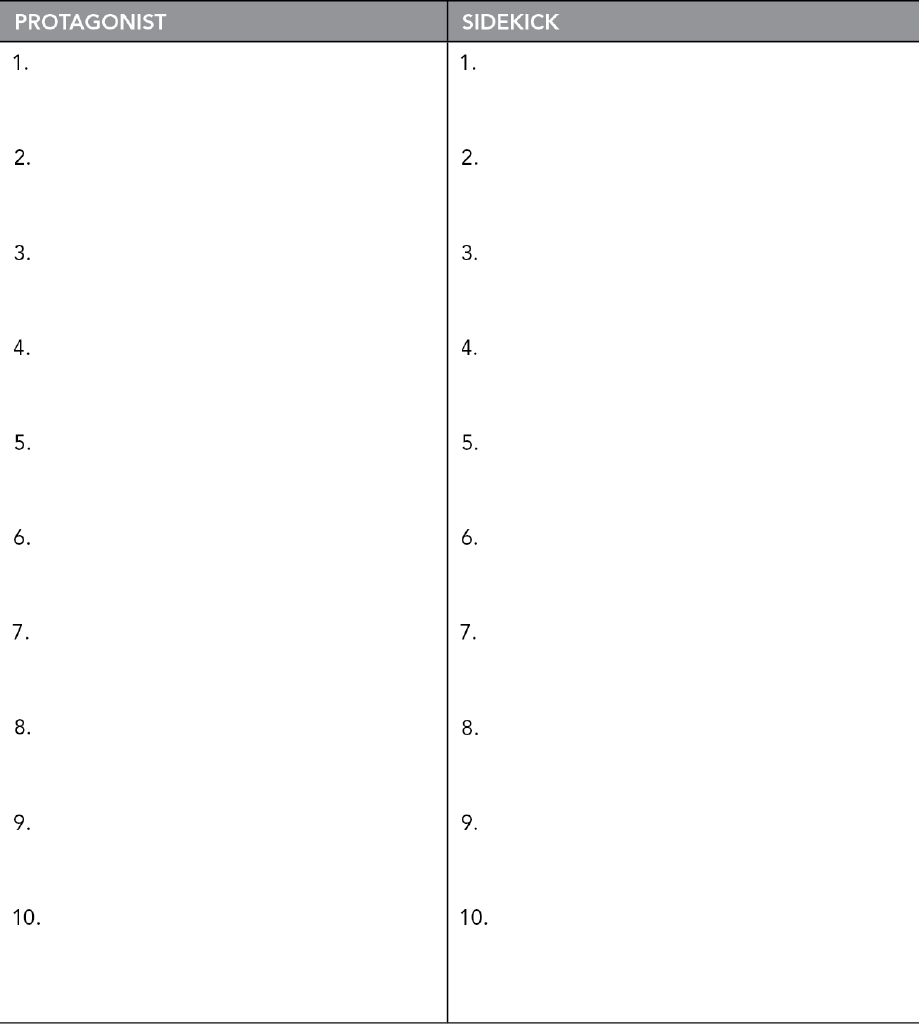

Now You Try: Traits for a Sidekick (Worksheet 6.1)

Make a list of your protagonist’s characteristics; list the opposites you could give to a sidekick. Circle the ones you like best.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

THE ADVERSARY

Every protagonist/mystery sleuth needs an adversary, too. This is not the villain but a good-guy character who drives your protagonist nuts, pushes his buttons, torments him, puts obstacles in his path, and is generally a pain in the patoot. She might be an overprotective relative or a know-it-all co-worker. Or she might be a police officer or detective who “ain’t got no respect” for the protagonist. She might be a boss who’s a micromanager or a flirt.

Sherlock Holmes’s adversary is Inspector Lestrade, who has much disdain for Holmes’s investigative techniques. In the same vein, Kathy Reichs’s forensic anthropologist, Temperance Brennan, has a tormentor in the person of Montreal police detective sergeant Luc Claudel. Their sparring is an ongoing element in her books. In Monday Mourning, Brennan finds out Claudel is going to be working with her on the case. She describes him this way:

Though a good cop, Luc Claudel has the patience of a firecracker, the sensitivity of Vlad the Impaler, and a persistent skepticism as to the value of forensic anthropology.

Then she adds:

Snappy dresser, though.

Conflict is the spice that makes characters come alive, and an adversary can cause the protagonist all kinds of interesting problems and complicate your story by throwing up roadblocks to the investigation.

An adversary may simply be thickheaded—for example, a superior officer who remains stubbornly unconvinced and takes the protagonist off the case. Or an adversary may be deliberately obstructive. For example, a bureaucrat’s elected boss might quash an investigation that threatens political cronies, or a senior reporter may fail to pass along information because he doesn’t want a junior reporter to get the scoop.

In developing an adversary, remember that he or she should be a character who is positioned to thwart, annoy, and generally get in your protagonist’s way. With an adversary in the story, the protagonist gets lots of opportunity to argue, struggle, and show her mettle and ingenuity.

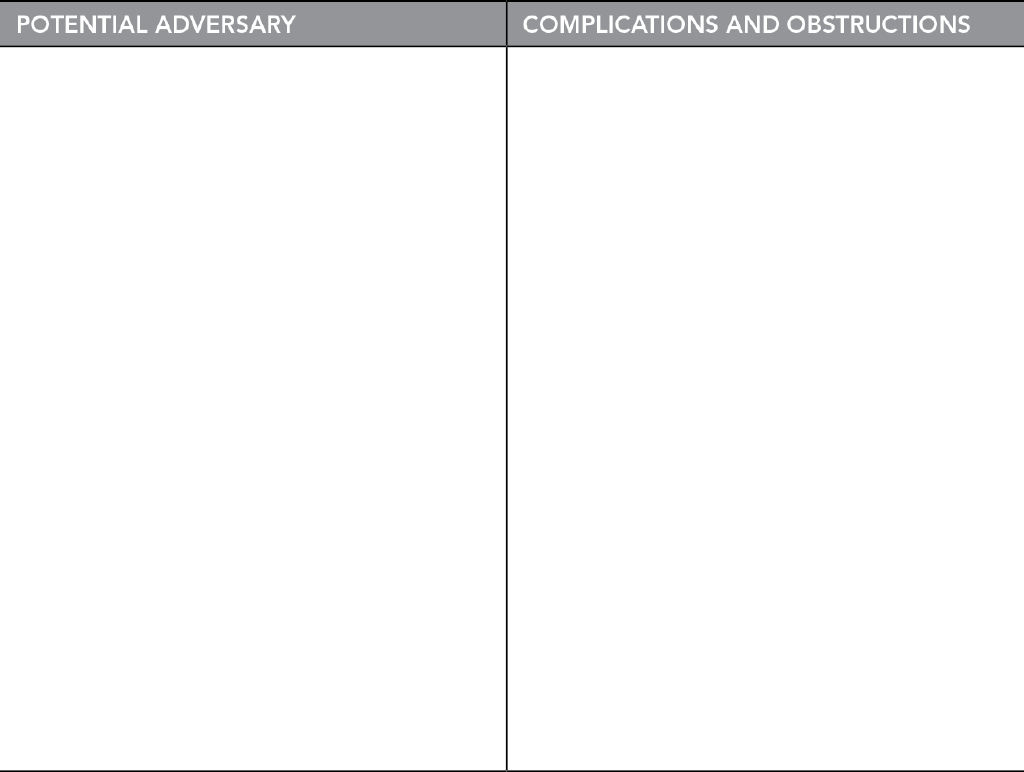

Now You Try: Find an Adversary (Worksheet 6.2)

Think about the characters you have planned for your novel. Which ones can act as adversaries? List the possibilities below, and brainstorm how each character can complicate your character’s life or obstruct the investigation.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

THE SUPPORTING CAST

The supporting character can include anyone in your protagonist’s life: a relative, a friend, a neighbor, a co-worker, or a professional colleague; the local librarian, waitress, or town mayor; even a pet pooch. Maybe this character will get ensnared in the plot and land in mortal danger. He might even take a turn as a suspect.

Supporting characters come with baggage, so pick yours carefully. If you give your protagonist young kids, you’ll have to deal with arranging for child care. A significant other? Be prepared to handle the inevitable attraction to that sexy suspect. A pet St. Bernard? He’ll have to be walked—twice a day. And your readers will worry about the dog, even if you don’t.

Supporting characters give your character a life, but each one should also play a critical role in the story. Here are some of the roles the supporting characters can play:

- sounding board

- possessor of special expertise

- provider of access to inside information

- bodyguard or tough guy

- caretaker or worry wart

- drudge

- mentor

- mole

- money bags

- influential cutter of red tape

- love interest

Supporting characters might start out as stereotypes: a devoted wife, a nagging mother-in-law, a bumbling assistant, a macho cop, or a slimy lawyer. They can be typecast during the planning phase. But when you start writing, you’ll want to push past the stereotypes and flesh out supporting characters, turning them into human beings who do things that surprise you. You don’t want supporting characters to hog the spotlight, but cardboard cutouts shouldn’t be clogging up your story either.

NAMING SUPPORTING CHARACTERS

Give each supporting character a name to match the persona, and be careful to pick names that help the reader remember who’s who.

Nicknames are easy to remember, especially when they provide a snapshot reminder of the character’s personality (Spike, Godiva, Flash) or appearance (Red, Curly, Smokey). Giving the character a name inspired by his ethnicity (Zito, Sasha, Kwan) makes it memorable, too. Avoid the dull and boring (Bob Miller) as well as the weirdly exotic (Dacron).

It’s not easy for readers to keep all your characters straight, so help them out:

- Don’t give a character two first names like William Thomas, Stanley Raymond, or Susan Frances.

- Vary the number of syllables in character names—it’s harder to confuse a Jane with a Stephanie than it is to confuse a Bob with a Hank.

- Pick names that don’t sound alike. If your protagonist’s sister is Leanna, don’t name her best friend Lillian or Donna.

- Pick names that start with different first letters. Keep track so you don’t end up with a Mary, a Melinda, and a Michelle.

Names are hard to come up with when you need them. An obvious source for inspiration is your local telephone directory. And there are lots of websites with baby names and others that serve up surnames by ethnicity. On Social Security’s “Popular Names by Decade” website, you can look up the decade in which the character was born and find out which names were popular then.

Whenever I discover a name I like, I add it to a list I keep on my computer. My list begins with Cecilia Spoon, a name I once found in a local paper. Perhaps it’s a bit too Dickensian, but I know one day I’ll find a home for it.

Create a list of “keeper” names, and add to it whenever you find one you like.

On Your Own: The Supporting Cast

- Name and profile your sidekick(s).

- name

- occupation

- major roles vis-à-vis your protagonist (sounding board, love interest, etc.)

- personality

- background

- strengths and weaknesses

- Name and profile your adversary:

- name

- position of power that enables this character to obstruct your sleuth

- relationship between your protagonist and this adversary

- Make a list of the other supporting characters your story needs. For each one, create a brief profile that includes these elements:

- name

- role in the story

- brief description (including age, gender, appearance, personality, and anything else you feel is important about this character)

Complete the Supporting Cast section of the blueprint at the end of Part I.