Chapter 18

Writing Investigation

Clues, Red Herrings, and Misdirection

“Another clue! And this time a swell one!”

—Joe to Frank in The Tower Treasure, the first Hardy Boys mystery by Franklin W. Dixon

Investigation is the meat and potatoes of a mystery novel. The sleuth talks to people, does research, snoops around, and makes observations. Facts emerge. Maybe an eyewitness gives an account of what he saw. A wife has unexplained bruises on her face. The brother of a victim avoids eye contact with his questioner. A will leaves a millionaire’s estate to an obscure charity. A bloody knife is found in a laundry bin. A love letter is discovered tucked into last week’s newspaper.

Some of this evidence will turn out to be clues that eventually identify the villain. Others are red herrings—evidence that misdirects the reader and leads to false conclusions. On top of that, some of the information your sleuth gathers will turn out to be nothing more than the irrelevant minutiae of everyday life, inserted into scenes to give a sense of realism and to camouflage the clues.

INVESTIGATING: OBSERVING AND INTERROGATING

A sleuth’s investigation centers on two main activities: observing and asking questions. If your sleuth is a professional detective or a police officer, then investigating might include examining the crime scene, questioning witnesses, staking out suspects, pulling rap sheets, checking DMV records, and going undercover. If your sleuth is a medical examiner, we’re talking autopsies and X-rays, analysis of stomach contents and DNA. If your character is an amateur sleuth, he’s going to sneak around, ask a lot of questions, and cozy up to the police.

How your sleuth investigates should reflect his skills and personality. Here is an example from one of Peter Robinson’s DCI Banks mystery novels, Friend of the Devil. DCI Banks observes the crime scene:

“Looks like we have manual strangulation to me, unless there are hidden causes,” Burns said, stooping and carefully lifting a strand of blond hair, gesturing toward the dark bruising under her chin and ear.

From what Banks could see, she was young, no older than his own daughter Tracy. She was wearing a green top and a white miniskirt with a broad pink plastic belt covered in silver glitter. The skirt had been hitched up even higher than it was already to expose her upper thighs. The body looked posed.

Banks is a pro. He’s unemotional and analytical in his observations, even though the victim is the same age as his daughter. His years of experience have shown him what dead bodies look like, so he knows when one seems “posed.”

Whether your sleuth schmoozes over tea with the victim’s neighbor, makes telephone calls to witnesses, formally interrogates a suspect, or huddles with colleagues to discuss blood spatter, your sleuth asks questions and gets answers. Talk, talk, talk. It can get pretty boring if all you’re doing is conveying information. So create a dynamic between the characters during the Q&A to hold the reader’s interest. Interrogation becomes interesting when the relationship between the characters has an electrical charge, some inner dynamic, as in this passage in which DCI Banks interrogates a suspect later in Friend of the Devil:

“Never mind the bollocks, Mr. Austin,” said Banks. “You told DC Jackman that you weren’t having an affair with Hayley Daniels. Information has come to light that indicates you were lying. What do you have to say about that?”

“What information? I resent your implication.”

“Is it true or not that you were having an affair with Hayley Daniels?”

Austin looked at Winsome, then back at Banks. Finally he compressed his lips, bellowed up his cheeks and let the air out slowly. “All right,” he said. “Hayley and I had been seeing one another for two months. We started about a month or so after my wife left. Which means, strictly speaking, that whatever Hayley and I had, it wasn’t an affair.”

“Semantics,” said Banks. “Teacher shagging student. What do you call it?”

“It wasn’t that,” said Austin. “You make it sound so sordid. We were in love.”

“Excuse me while I reach for a bucket.”

“Inspector! The woman I love has been murdered. The least you can do is show some respect.”

“How old are you, Malcolm?”

“Fifty-one.”

“And Hayley Daniels was nineteen.”

With his word choice (bollocks, shagging) and attitude (“Excuse me while I reach for a bucket.”), Banks shows his working-class roots and his disdain for Malcolm Austin. He’s not at all impressed with this man’s pedigree as a teacher, and he doesn’t suffer fools. His disgust with this man who seduced a young woman is more than professional; it’s personal—the victim reminds Banks of his own daughter.

Notice how Robinson uses body language as subtext, conveying to the reader a character’s emotions without spelling it out, letting the reader do the work of interpreting:

Austin looked at Winsome, then back at Banks. Finally he compressed his lips, bellowed up his cheeks and let the air out slowly.

That physical description, inserted in the middle of spare back-and-forth dialogue, highlights a tipping point—a transition between Austin’s insistence that he wasn’t having an affair with the victim and his confession that he was. Instead of rushing past this key moment, Robinson opens it up , slowing the reader down and drawing attention to the shift by inserting a physical description between the lines of dialogue.

Look for tipping points in your novel where the emotional balance shifts or a revelation comes to light. Open those tipping points by slowing down the narrative, but don’t bang your reader over the head with them or spoon-feed conclusions. Often you can let the reader interpret what it means.

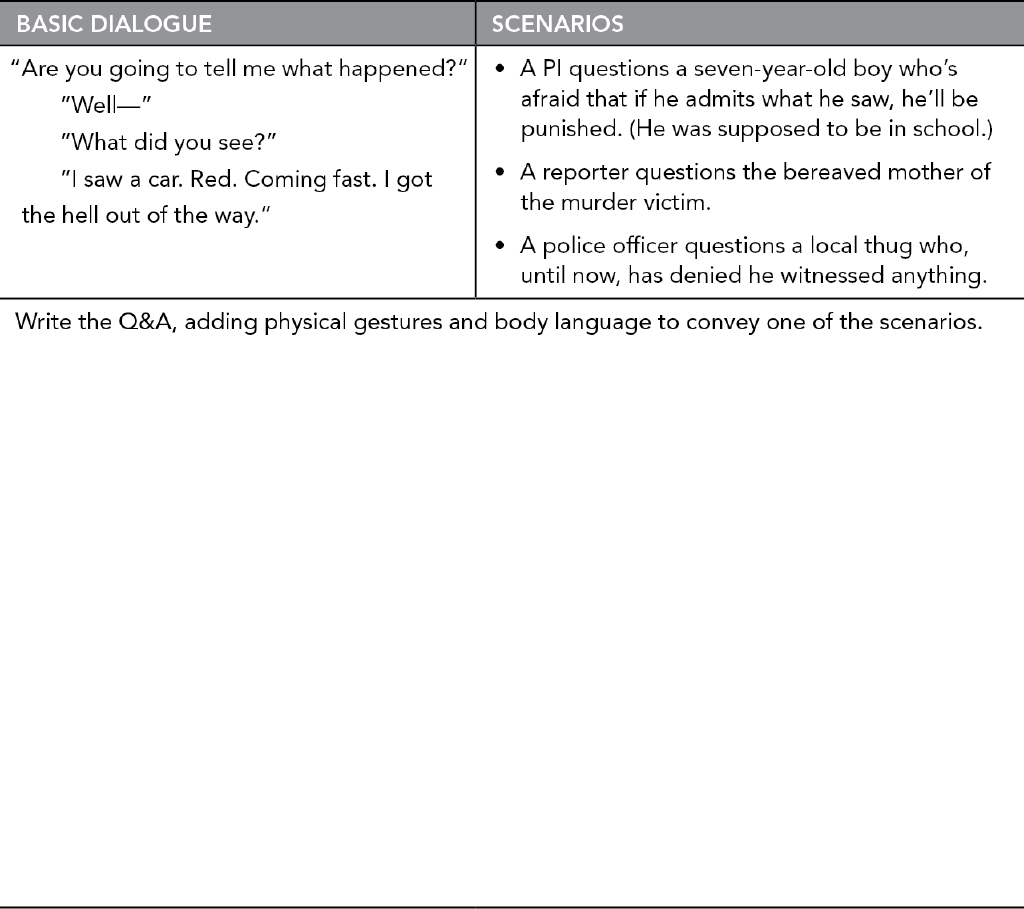

Now You Try: Nuance Q&A

Here are two examples in which body language conveys inner dynamics and shows the relationship between characters. The bolded dialogue in both passages is identical. Read and analyze. Which Cassandra is more likely telling the truth, and how does the body language suggest that?

| Q&A 1 | Q&A 2 |

|---|---|

I reached out and touched Cassandra’s arm. “Are you going to tell me what happened?” She looked away. “Well—” “What did you see?” She looked around, frantic for a moment, cornered, then swallowed and sat back in her chair. “I saw a car,” she said. “Red. Coming fast. I got the hell out of the way.” | I pulled over a chair and pushed Cassandra down into it. “Are you going to tell me what happened?” “Well—” She shrugged me off and fluffed her hair. “What did you see?” She gave me a sideways look, the flicker of a smile. “I saw a car.” She stared down at her fingernails, picked at the peeling candy-apple red polish. “Red. Coming fast. I got the hell out of the way.” |

In Q&A 1, I intended to make the reader think that Cassandra is telling the truth. By having her seem frantic and then resigned, and swallowing before she says what she saw, I tried to convey fear and reluctance and to suggest that she may be telling the truth. Cassandra in Q&A 2 shrugs, doesn’t seem to care, gives a flicker of a smile, and then picks at her red nail polish before she says the car was red—maybe it occurs to her at that moment that she should say the car is red. These details are designed to suggest that she’s lying.

Now You Try: Adding Body Language (Worksheet 18.1)

Combine physical gestures, internal dialogue, and body language with the dialogue below to develop one of these scenarios. Alter the word choice and add more dialogue to convey the dynamics of the scenario you pick.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

Blending Clues and Red Herrings

A clue can be just about anything:

- an object the sleuth discovers (a bloody glove)

- the way a character behaves (he keeps his hands in his pockets)

- a revealing gesture (a woman straightens her boss’s collar)

- what someone says (“Julia Dalrymple deserved to die.”)

- what someone wears (a locket stolen from the victim)

- an item that doesn’t fit with the way the person presents himself or his history (a suspect’s fingerprint is lifted from a room the suspect says she was never in)

Here are some techniques that enable you to play fair and, at the same time, keep the reader guessing:

- Emphasize the unimportant; deemphasize the clue. The reader should see the clue but not recognize its significance. For example, the sleuth investigates the value and provenance of a stolen painting and pays little attention to the identity of the woman who sat for the portrait.

- Establish a clue before the reader can grasp its significance. Introduce the key information before the reader understands the context it fits into. For example, the sleuth strolls by a character spraying her rose bushes before discovering that a neighbor was poisoned by a common herbicide.

- Have your sleuth misinterpret the meaning of a clue. Your sleuth misinterprets evidence that takes the investigation to a dead end. For example, the victim is found in a room with the window open. The sleuth thinks that’s how the killer escaped and goes looking for a witness who saw someone climbing out of the house. In fact, the window was opened to let out telltale fumes.

- Have the clue turn out to be something that should be there but isn’t. The sleuth painstakingly elucidates what happened, failing to notice what should have happened but didn’t. The most famous example is from the Sherlock Holmes story “Silver Blaze.” Holmes deduces there could not have been an intruder because the dog didn’t bark.

- Scatter pieces of the clue in different places and mix up the logical order. Challenge your reader by revealing only part of a clue at a time. For instance, the sleuth might find a canary cage with a broken door in the basement, along with other detritus; later the sleuth has a “Wait a minute!” realization when he discovers the dead canary with its neck wrung.

- Hide the clue in plain sight. Tuck the clue among so many other possible clues that it doesn’t stand out. For example, the murder weapon, a nylon stocking, might be neatly laundered and folded in the victim’s lingerie drawer. Or the sleuth focuses on the water bottle, unopened mail, pine needles, and gas station receipt on the floor of the victim’s car and fails to recognize the significance of a telephone number written in the margin of the map.

- Draw attention elsewhere. Have multiple plausible alternatives vying for the reader’s attention. For example, the sleuth knows patients are being poisoned. He focuses on a doctor who gives injections and fails to notice the medic who administers oxygen.

- Create a time problem. Manipulate time to your own advantage. For example, suppose the prime suspect has an alibi for the time of the murder. Later the sleuth discovers that the time of the alibi or the time of death is wrong.

- Place the real clue right before a false one. People tend to remember what was presented to them last. For example, your sleuth notices that the stove doesn’t light properly and immediately after that discovers an empty prescription bottle, marked with the label “Poison,” stuffed in the trash. Readers (and your sleuth) are more likely to remember the hidden bottle than the malfunctioning stove that preceded it.

- Camouflage a clue with action. If you show the reader a clue, insert some extraneous action at the same time to distract attention. For example, your sleuth gets mugged while reading a flyer posted on a lamppost; the mugging turns out to be irrelevant, but the flyer contains an important clue.

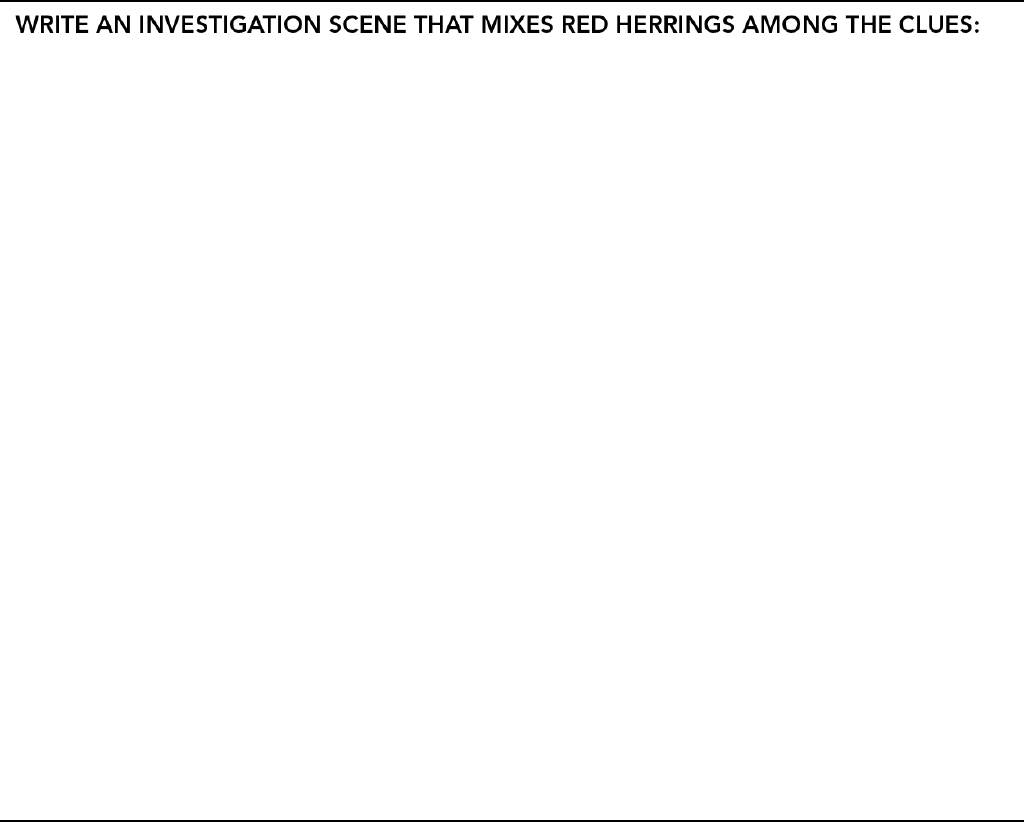

Now You Try: Mix Up Clues and Red Herrings (Worksheet 18.2)

Write a few paragraphs in which your sleuth does one of the following:

- inspects a murder scene

- searches a victim’s bedroom

- examines a suspect’s car

Have your sleuth find at least one real clue that implicates the villain, but camouflage it among false clues and extraneous details of everyday life.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

PLAYING FAIR

In a mystery novel, it’s considered bad form to flat-out withhold information that the narrator knows. It can be infuriating when an author withholds, even temporarily, some important piece of information that the point-of-view character knows.

Here’s an example:

Sharon’s cell phone rang.

“Sorry,” she told Bob. “This could be important.”

She flipped the phone open and pressed it to her ear. “Hello?”

Sharon recognized the caller’s voice, the last person she’d expect to call her after all that had happened. “What’s up?” she said, trying not to sound surprised.

“You need to know this—” the caller began.

As Sharon listened, she found herself pressing against the car door, trying to insert a few extra inches between herself and Bob. Bob was eyeing her closely, and his unconcerned look suddenly seemed no more than a thin veneer.

The chapter ends, and the reader doesn’t discover for twenty pages the identity of the caller or what troubling information that person imparted. Never mind that we’ve been hanging out in Sharon’s head for the last hundred pages and she’s been blabbing everything she sees, hears, feels, and thinks. Now, all of a sudden, she plays coy with this critical tidbit.

The reader and the sleuth should realize the identity of the culprit at about the same time. Authors succumb to the temptation of withholding information the narrator knows to create suspense. When they do, they cheat the story and exasperate readers. I know, I know, mystery authors get away with this shtick all the time, but it’s a cheap trick. Here’s my advice: Don’t succumb.

This is why guilty narrators are problematic in a mystery. They know too much. But plenty of mystery writers have managed to pull off a villainous narrator, keeping the character’s identity hidden without enraging their readers. For example, Peter Clement’s The Inquisitor is written from the point of view of a particularly chilling villain who gets his jollies bringing terminal patients near death:

“Can you hear me?” I whispered, holding back on the plunger of my syringe.

“Yes.” Her eyes remained shut.

I leaned over and brought my mouth to her ear. “Any more pain?”

“No. It’s gone.”

“Do you see anything?”

“Only blackness.” Her whispers rasped against the back of her throat.

“Look harder! Now tell me what’s there.” I swallowed to keep from gagging. Her breath stank.

“You’re not my doctor.”

“No, I’m replacing him tonight.”

Notice that by writing this passage in first person, Clement not only conceals the villain’s identity but also the villain’s gender. This subterfuge leaves the author free to cast suspicion on both male and female characters.

But it’s cheating to spend chapter after chapter in a character’s head, only to reveal in a final climactic scene that she’s been hiding one small detail: She did it. You might get away with it if the character is an unreliable narrator who can’t remember (she has amnesia), doesn’t realize (she’s delusional, naïve, simpleminded, or bamboozled), or can’t admit even to herself that she’s guilty.

CONFUSION: AN INTEREST KILLER

Your goal is to misdirect but never to confuse. Lead the reader down a series of perfectly logical primrose paths—your reader must always feel grounded, even if the story is veering onto a false path. Set too many different possible scenarios spinning at once, or overwhelm your reader with a cacophony of clues, red herrings, and background noise, and your baffled reader will get frustrated and set the book aside—permanently.

As you write, keep track of the different scenarios and of the clues that implicate and exonerate each suspect. Also, be sure to track who knows what and when they know it—particularly if you’re writing from multiple viewpoints. If you’re confused, your reader is sure to be.

COINCIDENCE: A CREDIBILITY KILLER

All of us are tempted, from time to time, to insert a coincidence into a storyline. Wouldn’t it be cool, you say to yourself, to have a character run into the twin sister she never knew she had in a hall of mirrors at a county fair? Dramatic, yes. Credible, no.

Never mind that Agatha Christie wrote a story that turns on a similar coincidence: A man runs into his unknown twin brother coming out of a drugstore; the evil twin then commits a murder and implicates his brother. Never mind that you once read a newspaper article about separated twins who ran into each other in a supermarket. Life is full of bizarre coincidences. You can’t put a coincidence like that in a mystery novel today and expect your work to be taken seriously.

Coincidence is most likely to creep in when you maneuver your character into position for the sake of your plot. Maybe your character needs to find out when and where a crime is going to occur, so you have him coincidentally find that information in a letter someone drops on the sidewalk. Or maybe your character needs to find a buried clue, so you give her the inexplicable urge to plant petunias and dig in just the right spot. Or maybe your character needs to know the scheme two characters are hatching, so he happens to pick up the phone extension and overhears them planning.

It’s much more satisfying if you come up with logical ways to maneuver your character into position to find the clues and red herrings your plot requires. Repeat after me: Thou shalt not resort to coincidence, intuition, clairvoyance, or divine intervention. In a mystery, logic rules and credibility is paramount.

If you do put coincidence in your story, at least have your point-of-view character comment on the absurdity of the coincidence. While it’s not the most elegant solution, at least it will keep the reader from dismissing you as a hack.

On Your Own: Writing Investigation

- Check out a how-to book about magic. Mystery authors do well to take a few pages from magicians, who have perfected the art of misdirection. My favorite is the classic by Henning Nelms, Magic and Showmanship. Take to heart his distinction between diversion (good showmanship) and distraction (poor showmanship).

- Write a scene in your novel in which your sleuth questions one of the other characters. Show the dynamic between the characters.

- Keep track of your clues, noting the key pieces of information you reveal throughout the investigation:

- the clue

- what it reveals

- who knows it and when

- whom it implicates