Chapter 15

Narrative Voice and Viewpoint

“I think point of view is a bugaboo for many beginning writers because so many terrifying things have been said about it. It is entirely a matter of feeling comfortable in the writing, the question of through whose eyes you should tell the story.”

—Patricia Highsmith, Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction

Writing is all about making choices, and one of the first choices you make when you sit down to write is who narrates. Which characters will get to tell their version of what happened? Will you be in one character’s head throughout, or will you let several characters speak to the reader?

When you read a Sherlock Holmes story, you get Watson’s version of events. Stephanie Plum puts her pungent spin on what goes down in Janet Evanovich’s Stephanie Plum series. One thing that made Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl such a blockbuster is that readers doesn’t know which of its two narrators, Amy or Nick, to believe. Then it turns out both of them are lying.

PICKING NARRATORS

Usually in a mystery, the sleuth tells some or all of the story. He functions much like a camera, and the scenes he narrates are filtered through his personal lens. The reader has access to his senses, emotions, and thoughts.

Some mystery novels have one narrator throughout. Others have two. Others have many. More than convenience should drive the decision to give a character viewpoint. There should be something important in that character’s firsthand experience of the events in the novel or in the past that will add complexity and power to the overall tale.

In Tess Gerritsen’s series featuring detective Jane Rizzoli and medical examiner Maura Isles, both characters get to narrate. Sometimes Gerritsen has to pick which one will one narrate a scene they’re both in. I asked her how she decides, and her answer surprised me. She said she chooses the character who is feeling the most off balance.

When you allow a character to narrate, you are inviting the reader inside that character’s head. In a mystery novel this can be a tricky proposition if that character knows a secret that you want to withhold from the reader.

Changing the Narrator Changes the Story

Who narrates a scene is a critical decision. The reader sees only what that character sees, is privy to his interpretation of the events, which are biased by his personality and past.

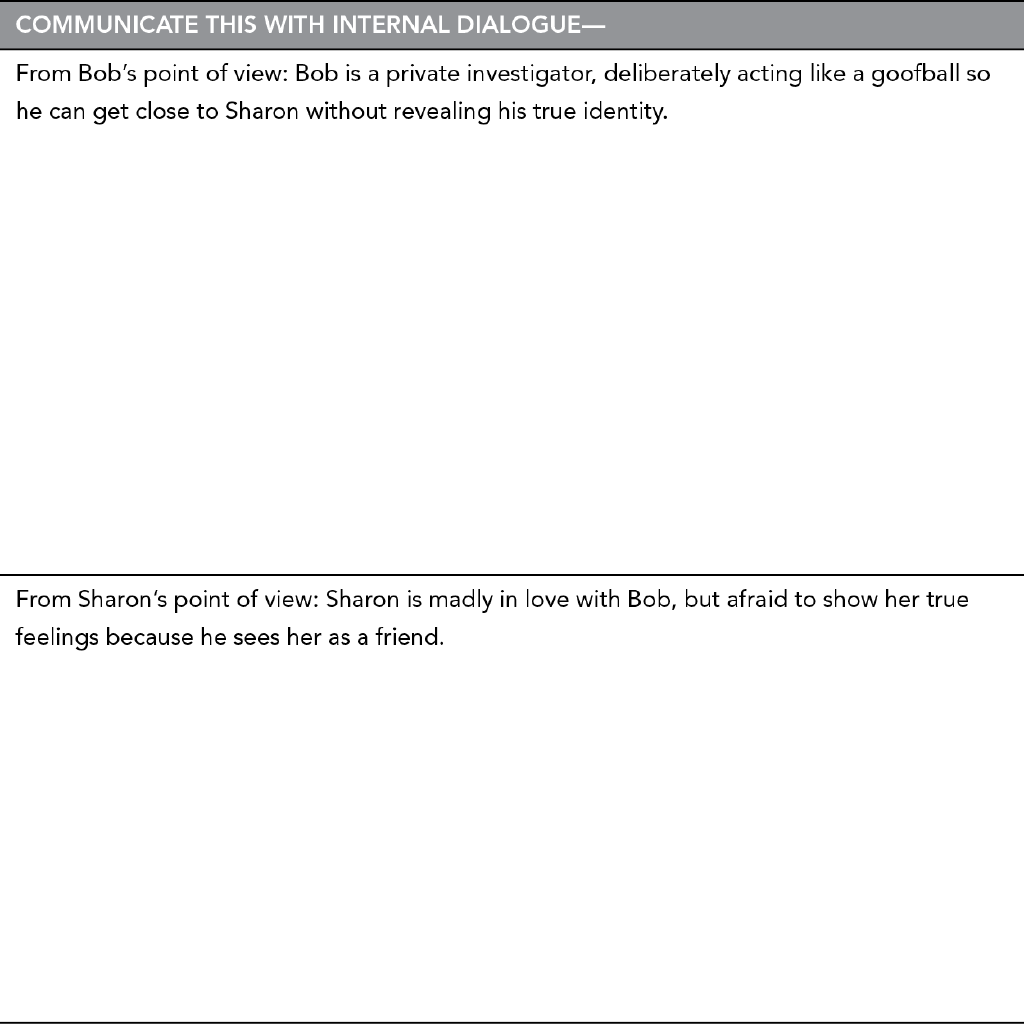

Here are two versions of the same action, written from the point of view of two different characters. Read each version, and think about how the change in point of view affects the story. Notice that only the dialogue (bolded) remains the same.

| Sharon’s Point of View | Bob’s Point of View |

|---|---|

“Sharon?” The voice echoed in the courtyard. I turned, and immediately wished I’d just kept going. “What do you want now, Bob?” My voice sounded strident. If only he’d back off, ease up on the full court press. I just wanted to get away, be by myself for a while. “Hold up a sec.” I stood there, barely able to keep myself from bolting for my car. His boot heels stomped across the concrete, crunching bits of broken glass. The flowers he held out were roses, shopworn, their heads already starting to droop. Pathetic, really. I suppressed a groan. | When I got there, Sharon was walking across the courtyard. Looked as if she was heading for her car. A minute later and I’d have missed her. I hid the flowers behind my back. I’d surprise her. “Sharon?” I yelled. My voice echoed in the courtyard. She paused and turned back. “What do you want now, Bob?” I felt my shoulders sag. Why had I bothered? You’re so pathetic—you just can’t take no for an answer, I heard my ex-wife’s hectoring voice in my head. But I couldn’t turn back now. “Hold up a sec.” I closed the space between us. Her eyes were hard, and there were lines of tension in her forehead. When I held out the flowers, her expression changed to pity. Should have known. Why the hell had I bothered? |

In both versions, the same action takes place: Bob calls out; Sharon stops; he gives her flowers. The dialogue is identical. The differences are in the narrator’s internal dialogue—and what a difference that makes.

Now You Try: Revise the Narrator (Worksheet 15.1)

Revise the scene between Sharon and Bob. Use only this dialogue:

Bob: “Sharon?”

Sharon: “What do you want now, Bob?”

Bob: “Hold up a sec.”

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

MAKING EACH NARRATOR’S VOICE MEMORABLE

If you were writing a memoir, the narrator’s voice would be your own. You’d tell the story of the events in your life from your perspective, sharing your thoughts and feelings along the way. Your language and word choice, jokes, cultural references, and metaphors would reflect who you are.

The challenge of writing fiction is to tell a story in a voice that’s not your own. You conjure the personality behind it and show who he is by how he tells the tale.

What does a strong voice look like? Meet Christopher John Francis Boone, a fifteen-year-old boy in Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time:

It was 7 minutes after midnight. The dog was lying on the grass in the middle of the lawn in front of Mrs. Shears’ house. Its eyes were closed. It looked as if it was running on its side, the way dogs run when they think they are chasing a cat in a dream. But the dog was not running or asleep. The dog was dead. There was a garden fork sticking out of the dog. The points of the fork must have gone all the way through the dog and into the ground because the fork had not fallen over. I decided that the dog was probably killed with the fork because I could not see any other wounds in the dog and I do not think you would stick a garden fork into a dog after it had died for some other reason, like cancer for example, or a road accident. But I could not be certain about this.

What happens in this brief passage? Not much, right? It’s narrated in the first person with Christopher trying to figure out what happened to his neighbor’s dog. But through what he observes, and how he tells us about it, we learn a great deal about him. He is logical, precise (he tells us it’s 7 minutes after midnight). Even though finding a dead dog might be traumatic to most boys, he is unemotional and observant, noticing the concrete facts of the situation, not its horror. This is amplified by his short, precise, and complete sentences; he never uses contractions. He almost sounds like a robot.

Consider next this excerpt in which Stella Hardesty confronts a friend’s abusive husband in A Bad Day for Sorry:

Stella lowered her gun to her side and let the Raven hang there casually. She could go from full dangle to aimed and ready to shoot in about a tenth of a second. That was a trick she’d worked on most of last winter when business was slow at the shop—sitting on her stool behind the cash register and practicing her draw, tucking the gun into the drawer when the bell at the door signaled a customer’s arrival.

She’s also taught herself to spin the thing on her finger just like Gary Cooper in High Noon, but that trick was strictly for her own enjoyment. She didn’t mind having a little flair, but she wasn’t an idiot: guns, after all, were serious business.

Again, not much happens. Stella is just standing there, her gun at her side. She’s narrating in third person. Her voice is tough and direct, and her sentences are laced with colorful phrases and a regional twang.

An analysis of the differences between Christopher Boone and Stella Hardesty reveals some pointers on how to create your own strong narrator:

- Directness: Christopher speaks in the first person, directly to the reader. Stella is rendered in third person, though it feels just as direct.

- Word choice, sentence structure: Christopher speaks in short, subject-verb-object sentences filled with specific details and simple language. Stella’s speech is much more colorful, her sentences varied in structure and laced with humor.

- Emotion: Christopher’s words feel like a blank façade; Stella’s are packed with dry humor and innuendo. We get the sense that Stella has a great deal of insight into her own emotions and actions, whereas Christopher does not.

- Tone: Christopher’s passage, even though it’s devoid of emotion, reveals to the reader how vulnerable he is because he doesn’t understand the nuance of the situation. Stella seems like someone who’s had all the protectin’ she needs in this lifetime, thanks very much.

To create a strong narrative voice, incorporate all these elements into your prose: directness, sentence structure, word choice, and tone. Channel your character’s personality. Revise until you’ve developed a narrative voice that satisfies you. Try to keep that voice in your head and on the page whenever that character narrates, all the way to the end of the book.

DETERMINING POINT OF VIEW (POV)

Decide at the outset in what point of view (POV) you’re going to write, and how many of your characters will narrate. This sounds pretty simple, and sometimes it’s clear to the writer which POV and narrative strategy is going to work best for a given manuscript. Other times the writer struggles, starting in first person and discovering part way through that it’s too limiting, or he starts the novel in third person, with multiple narrators, but then feels the story loses its focus and needs the emotional intensity of a single first-person narrator.

Of course you can begin writing in first person, for example, and then decide that third person works better. But you’ll have to rewrite everything you’ve written up to that point. I know because I’ve done it. To avoid a major rewrite halfway through, experiment early with different point-of-view choices. See which feels right for the story you want to tell.

Here are the point-of-view choices:

- First person: One character holds the camera; the narrative is written using the pronouns I and me.

- Third-person limited: One character holds the camera; the narrative is written using the pronouns he/she and him/her.

- Multiple third person: One character at a time holds the camera; the narrative is written using the pronouns he/she and him/her.

- Omniscient: The camera can be anywhere; the narrative is written using the pronouns he/she, him/her, and they/them.

Let’s take a closer look at the strengths and weaknesses of each of these choices.

First-Person POV

Many mysteries are written entirely from the point of view of a sleuth who is a first-person narrator. Series authors often choose first person because it helps create a bond between the reader and the protagonist, which is essential in a successful series.

Robert B. Parker wrote Hugger Mugger, a Spenser series novel, in first person. Read this example to see how an expert wields first-person viewpoint:

I was at my desk, in my office, with my feet up on the windowsill, and a yellow pad in my lap, thinking about baseball. It’s what I always think about when I’m not thinking about sex. Susan says that supreme happiness for me would probably involve having sex while watching a ball game. Since she knows this, I’ve never understood why, when we’re at Fenway Park, she remains so prudish.

With a first-person sleuth narrator, Parker gives the reader an intense and personal inside view of his character. First-person narrative also reinforces the illusion that the sleuth and the reader are solving the puzzle together, finding clues, getting lured into blind alleys, surviving physical peril, until they finally discover the truth.

Series authors with first-person sleuth narrators include some of the biggies: Sue Grafton, Jonathan Kellerman, Lawrence Block, Kathy Reichs, Linda Fairstein, and James Patterson.

A single first-person narrator is the simplest to manage for new writers. It’s easier to get a single point of view under control, and you only have to create one strong narrator’s voice.

But here’s the rub: When a first-person narrator gets locked in a dark, dank basement for days, your story gets held captive with him. If your first-person narrator isn’t present when something dramatic (like the murder) happens, you can’t dramatize it. Your character has to find out indirectly by visiting the scene of the crime, hearing it described by another character, reading the autopsy report or newspaper article, or interviewing surviving witnesses. Events perceived after the fact or secondhand don’t pack nearly the wallop as those experienced firsthand and dramatized as they unfold.

Third-Person Limited POV

You can convey an equally strong sense of the main character by writing in third-person limited. The story is still narrated by one character, but writing in third-person limited enables you to insert more distance between the character and the reader, providing a narrator’s filter for the point-of-view character’s experience.

Consider this example from P.D. James’s Devices and Desires:

By four o’clock in the morning, when Alice Mair woke with a small despairing cry from her nightmare, the wind was rising. She stretched out her hand to click on the bedside light, checked her watch, then lay back, panic subsiding, her eyes staring at the ceiling, while the terrible immediacy of the dream began to fade, recognized for what it was, an old spectre returning after all these years, conjured up by the events of the night and by the reiteration of the word “Murder,” which since the Whistler had begun his work seemed to murmur sonorously on the very air.

Did you notice how James inserts distance between the reader and the point-of-view character? It’s written as if we’re looking down on Alice, interpreting her actions, reading her thoughts.

If you want to insert this kind of distance between your point-of-view character and the narrative, write in third person instead of in first person. You’ll be able to draw back the camera from time to time and show the reader a bigger picture than what your point-of-view character can see.

Keep in mind, though, that narrative written in the third-person limited is more difficult to control than narrative written in first person. It’s easy to slip out of one character’s head and into another’s or slide into omniscience. And you’re still limited in what you can show the reader since a single character tells the story.

Multiple Third-Person POV

Thriller writers often opt for multiple points of view. They write in third person, with the camera close over the shoulder of one character at a time. Different scenes can be narrated by different characters.

With multiple points of view, you have more flexibility in telling your story. Shifting the point of view enables you to create considerable dramatic tension and suspense. For example, suppose you have two main characters, partner sleuths. When one of them gets trapped in a cave, you can let the other character take over, narrating his struggle to find her. Shift back to the trapped partner, and show her feeling colder and wetter as water rises. Shift back to the other partner, searching frantically, trying to find the cave entrance.

Using multiple points of view can feel liberating. You can dramatize virtually anything—just shift to the point of view of a character who’s there. You can even write scenes from the villain’s point of view.

Best-selling authors who excel at using multiple points of view include Lisa Scottoline, Val McDermid, Tony Hillerman, and Dennis Lehane. These authors are also big talents with a lot of writing experience under their belts.

Don’t underestimate the skill it takes to create a single strong, distinct narrator’s voice, never mind more than one. Too often, inexperienced writers attempt to write in multiple points of view, resulting in a book that feels disjointed, without a coherent story line or an emotional core.

Third-Person Omniscient POV

With an omniscient viewpoint, the narrator is a disembodied presence, a storyteller who sees all and knows all. The omniscient narrator can hover above the action, offer ongoing commentary that goes beyond the perspective of the individual characters, provide emotional insight, and even disclose information that none of the characters knows.

Omniscient viewpoint was often used in nineteenth-century novels like Pride and Prejudice. It’s a technique modern writers use more often in fantasy and science fiction. Examples include Philip Pullman’s The Golden Compass, Frank Herbert’s Dune, and the Harry Potter books.

The omniscient-third-person point of view offers the narrator the advantage of going anywhere and seeing anything. If the sleuth gets trapped in a cave, the narrator can describe the deserted scene a few feet outside the cave’s wall where birds are singing and the sun is shining.

However, an omniscient narrator who picks and chooses what information to share can make the reader feel distanced and manipulated, turning the mystery into more of a tease than a puzzle. In addition, using the omniscient third person can weaken the bond between the reader and the sleuth.

Many authors shun the omniscient voice, concerned that it seems stilted and old-fashioned. Still, it has its place. Plenty of authors use it occasionally to pull the camera back and show the reader a bird’s-eye view of the goings on.

Here’s an example of a modern master using the omniscient point of view from P.D. James’s Death Comes to Pemberly.

It was generally agreed by the female residents of Meryton that Mr. and Mrs. Bennet of Longbourn had been fortunate in the disposal in marriage of four of their five daughters. Meryton, a small market town in Hertfordshire, is not on the route of any tours of pleasure, having neither beauty of setting nor a distinguished history, while its only great house, Netherfield Park, although impressive, is not mentioned in books about the county’s notable architecture. The town has an assembly room where dances are regularly held but no theatre, and the chief entertainment takes place in private houses where the boredom of dinner parties and whist tables, always with the same company, is relieved by gossip.

In an authorial voice, James introduces the readers to Meryton and establishes the context for this modern murder-mystery sequel to Pride and Prejudice.

A little omniscience goes a long way in a mystery novel, so use it sparingly.

Sliding Point of View (Head Hopping)—A No-No

Whether you tell your story in first or third person, or have a single point-of-view character or several, anchor the narration in each scene in a single character’s head.

If Bob is the narrator, you can show his thoughts and feelings:

Bob was afraid he was going to throw up.

If Linda is the narrator, the same content becomes:

Bob looked like he was going to throw up.

Don’t let the viewpoint slide from head to head. For instance, suppose you write a scene in which police arrive and investigate a shooting. You begin writing the scene from the point of view of the detective in charge. You can show the detective observing blood spatter, gunshot residue, and the position of the corpse. You can show the detective questioning the victim’s boyfriend and interpreting his reactions. But to reveal what the boyfriend really thinks and feels would require a viewpoint shift.

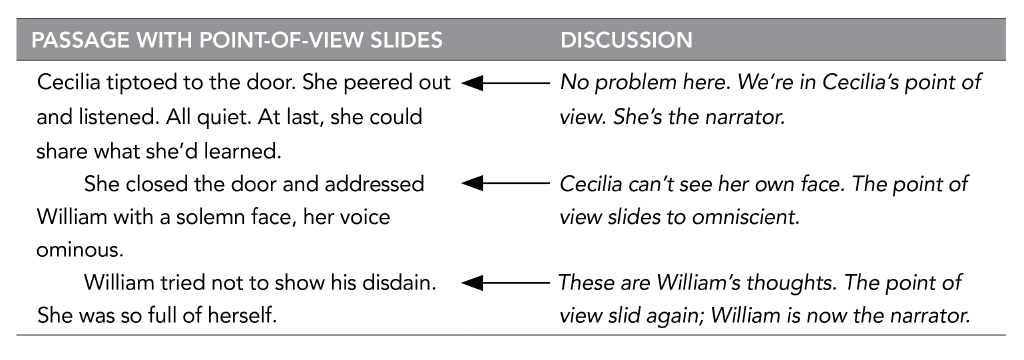

Reading a scene where the point of view slides from one character’s head to another can feel like riding in a car with loose steering. Here’s an example. Cover up the discussion on the right, and try to find the spots where the viewpoint slides. Then read the discussion.

To keep the point of view from sliding, keep asking yourself: Who is telling the story? Then, as you write, anchor yourself in that character’s head. Write the scene as that character experiences it, revealing his thoughts and feelings, his observations of other characters, and his interpretation of what other characters might be thinking and feeling.

You can have a different narrator tell the story in the next scene, but try not to head hop within a single scene.

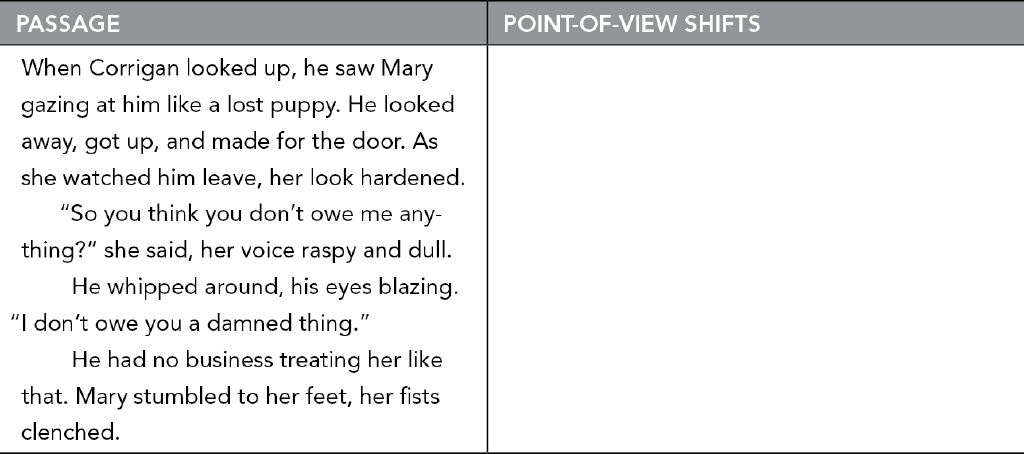

Now You Try: Slipping and Sliding Point of View (Worksheet 15.2)

Read the passage below and find the point-of-view shifts.

Revise the entire passage so Corrigan is the only narrator.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

On Your Own: Narrative Voice and Point of View

- Scan through some of your favorite mysteries; examine the point-of-view choices the authors make:

- First person or third?

- Single or multiple narrators?

- Open one of your favorite mysteries to scenes at the beginning, middle, and end of the book. In each scene, analyze how the author creates a distinct, compelling narrative voice. Look at each of the following:

- directness

- sentence structure

- word choice

- tone

- Examine the scenes you’ve written so far, and ask yourself:

- Are you satisfied with your choice of first- or third-person narrative?

- Are you satisfied with the character(s) you picked to tell the story?

- Have you kept control of the point of view, or have you allowed it to slip and slide?

- Continue writing. Keep in mind that in every scene, you should be telling the story in a single character’s (and not your authorial) voice.