Chapter 11

Writing a Dramatic Opening

“I find that most people know what a story is until they sit down to write one.”

—Flannery O’Connor

No pressure, but the opening of your book is the gatekeeper in determining whether your novel will sell. If your opening is weak, it won’t matter if chapter two is a masterpiece. Editors and agents and booksellers and librarians and readers will stop reading before they get there.

If you completed your blueprint, you’ve already scoped out a dramatic scene to open your novel. You know who’s in the scene and what’s going to happen to propel the novel forward.

Your opening scene can be long or short. It can be action packed, or moody and rich in description, or skeletal and spare. It may contain a vivid sense of setting or a strong shot of character. Regardless of what’s in that scene, the reader should have some idea of what the novel is going to be about after reading it, or at least have a good sense of the theme. Most of all, when they finish, readers should be eager to keep reading.

ANALYZING A DRAMATIC OPENING

So what makes for a good dramatic opening? In the absence of any useful rules, the best I can offer is an example. Consider this excerpt from the opening scene of Julia Spencer-Fleming’s award-winning debut novel, In the Bleak Midwinter.

| Think about: | Opening scene from In the Bleak Midwinter by Julia Spencer-Fleming |

|---|---|

How does the opening sentence set up the scene? What’s the out-of-whack event, and how does it pull the reader forward? In what tense is this told, and from which character’s point of view? What do we know about the setting? What’s the weather and time of day? What do we learn about Russ Van Alstyne? Why does this event matter to this protagonist? What does this opening scene suggest that the book is going to be about? Does this opening develop plot or character? | It was one hell of a night to throw away a baby. The cold pinched at Russ Van Alstyne’s nose and made him jam his hands deep into his coat pockets, grateful that the Washington County Hospital had a police parking spot just a few yards from the ER doors. A flare of red startled him, and he watched as an ambulance backed out of its bay silently, lights flashing. “Kurt! Hey! Anything for me?” The driver waved at Russ. “You heard about the baby?” “That’s why I’m here.” Russ waved, then pushed open the antiquated double doors to the emergency department. … “Hey! Chief!” A blurry form in brown approached him. Russ tucked his glasses over his ears and Mark Durkee, one of his three night shift officers, snapped into focus. As usual, the younger man was spit-and-polished within an inch of his life, making Russ acutely aware of his own non-standard-issue appearance: wrinkled wool pants shoved into salt-stained hunting boots, his oversized tartan muffler clashing with his regulation brown parka. “Hey, Mark,” Russ answered. “Talk to me.” The officer waved his chief down the drab green hallway toward the emergency room. The place smelled of disinfectant and bodies, with a whiff of cow manure left over by the last farmer who had come in straight from the barn. … “How’s the baby look?” “Fine, as far as they can tell. He was wrapped up real well, and the doc says he probably wasn’t out in the cold more’n a half hour or so.” Russ’ sore stomach eased up. He’d seen a lot over the years, but nothing shook him as much as an abused child. He’d had one baby-stuffed-in-a-garbage-bag case when he’d been an MP in Germany, and he didn’t care to ever see one again. |

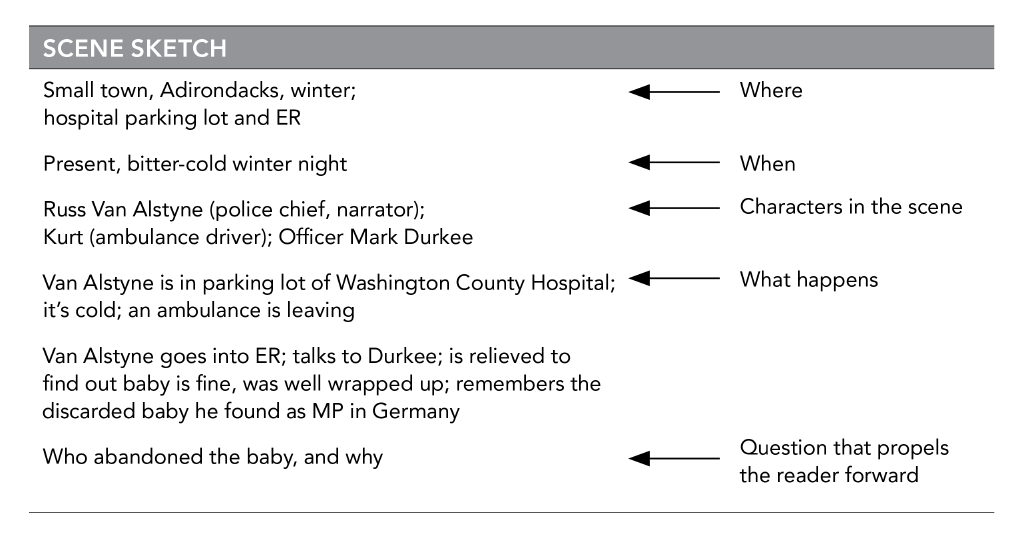

Plot and character take equal weight in this excerpt. It’s as much about introducing police chief Russ Van Alstyne (one of the series’ two protagonists) as it is about setting up the story of an abandoned baby. Every sentence, every detail is a deliberate choice, and by the end, the reader knows that the novel will answer two questions: Who abandoned that baby, and why?

It was one hell of a night to throw away a baby.

Right away, the opening establishes the out-of-whack event: a baby has been abandoned. This intriguing opening is a line of internal dialogue that puts the reader firmly in Russ’s head. The point of view is the third-person limited, and we experience this scene as if the camera is looking through Van Alstyne’s eyes. His thoughts filter the images we see. It’s written in the past tense, but the feeling is one of immediacy.

The cold pinched at Russ Van Alstyne’s nose and made him jam his hands deep into his coat pockets, grateful that the Washington County Hospital had a police parking spot just a few yards from the ER doors.

You’ve probably heard the author’s adage “Show; don’t tell.” Throughout this brief passage, Spencer-Fleming shows us what Van Alstyne is like. She shows that he is chief of police: The ambulance driver addresses him as “Chief,” and he parks his car in a police parking spot. She also shows how cold it is with the phrase “the cold pinched his nose” and with the way Van Alstyne jams his hands into his pockets. The bitter cold isn’t mentioned just for ambience; it brings home to the reader how dangerous it was for that baby to be left on the church steps.

The place smelled of disinfectant and bodies, with a whiff of cow manure left over by the last farmer who had come in straight from the barn.

In a few descriptive phrases, we get a visceral sense of place. We know this is a hospital, and we know it’s located somewhere rural.

We get a detailed description of what Van Alstyne is wearing (wrinkled wool pants shoved into salt-stained hunting boots) as he mentally compares himself to a younger officer (spit-and-polished within an inch of his life.) Van Alstyne is a guy with more than a few miles on him who doesn’t fuss with his appearance.

“How’s the baby look?” Van Alstyne asks. He cares. And already we’re wondering: Who left this baby on the church steps, and what happened to the baby’s mother?

“He was wrapped up really well, and the doc says he probably wasn’t out in the cold more’n a half hour or so.”

Clues!, thinks the astute reader. Someone wrapped that baby up well. Maybe that someone was even watching to be sure the baby was found in time.

Here’s what Spencer-Fleming doesn’t give the reader: a whole lot of backstory. Backstory is background information about how a character arrived at this particular place and time. When a load of backstory has been dumped into the opening chapter, it’s a sure sign that the novel was written by a novice. At this point we get only a whiff of Van Alstyne’s past and a hint of why an abandoned baby matters to him:

He’d had one baby-stuffed-in-a-garbage-bag case when he’d been an MP in Germany, and he didn’t care to ever see one again.

That’s all the reader needs to know at this point.

Now You Try: Analyze a Dramatic Opening

Reread the opening scenes of some of your favorite mystery novels. Pay careful attention to how the authors handle these five elements:

- the opening paragraph

- the final paragraph

- how characters are introduced

- the setting and how it’s established

- the unanswered question that sets up the novel

SKETCHING OUT A DRAMATIC OPENING

As an exercise in chapter eight, you wrote a description of your opening scene. If you have a clear picture in your mind of exactly what happens in the scene, you may feel you can jump right in and write the dramatic opening of your novel. But if you find that blank page daunting, sketch out the scene before you try to write it.

Here’s an example of what the sketch for a scene looks like, using the opening of In the Bleak Midwinter as an example.

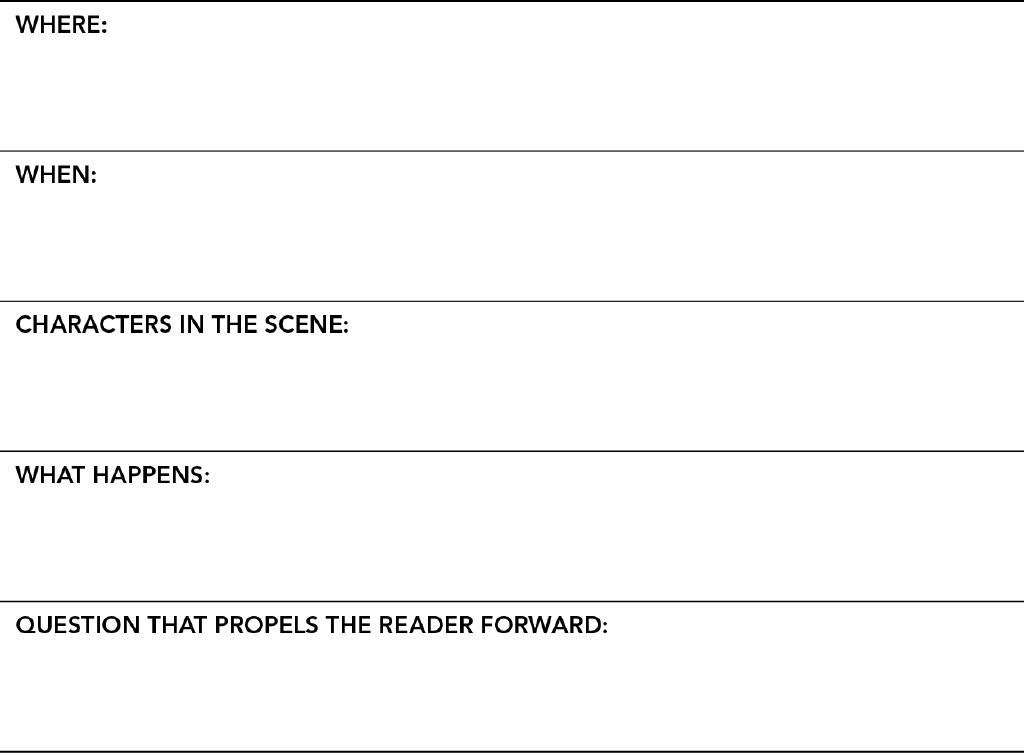

Now You Try: Sketch Out a Dramatic Opening (Worksheet 11.1)

Review your description of your novel’s dramatic opening. Then visualize the scene in your mind. Sketch it out below.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

WRITING THE DRAMATIC OPENING LINE

One way to effectively launch the opening scene is to jump right into the action. Here are some opening lines that catapult the reader into the story:

When the first bullet hit my chest, I thought of my daughter. (No Second Chance, Harlan Coben)

She’d been brutally stabbed and slashed more times than Carella chose to imagine. (Widows, Ed McBain)

Gordon Michaels stood in the fountain with all his clothes on. (Banker, Dick Francis)

The house in Silverlake was dark, its windows as empty as a dead man’s eyes. (The Concrete Blonde, Michael Connelly)

I was fifteen years old when I first met Sherlock Holmes, fifteen years old with my nose in a book as I walked the Sussex Downs, and nearly stepped on him. (The Beekeeper’s Apprentice, Laurie R. King)

Augie Odenkirk had a 1997 Datsun that still ran well in spite of high mileage, but the gas was expensive, especially for a man with no job, and City Center was on the far side of town, so he decided to take the last bus of the night. (Mr. Mercedes, Stephen King)

Annie Holleran hears him before she sees him. (Let Me Die in His Footsteps, Lori Roy)

Your opening line is important, but don’t obsess about it. Just write an opening line that drops the reader into the scene, and keep going. You can perfect it later.

WRITING THE DRAMATIC OPENING SCENE

The first scene of your book presents some unique problems. Your primary job is to get your story moving. At the same time, you need to introduce your characters, the setting, and the situation. It’s a tall order, and it’s easy to bore the reader with too much information or to confuse him by laying too little groundwork.

Keep your eye trained on the story you’re setting up—something intriguing has to happen. Lay in just enough character and setting description to orient the reader. You have the rest of the book to fill in the blanks.

Write the opening scene using the elements you sketched out. You can make revisions later, applying lessons from later chapters in this book, such as setting the scene, introducing characters, writing dialogue and internal dialogue, and creating action.

ENDING THE DRAMATIC OPENING WITH FORWARD MOMENTUM

End your dramatic opening scene with an unanswered question that is implied or stated. Your goal is to make it impossible for the reader to put down your novel.

Here’s how Harlan Coben ends the opening scene of No Second Chance:

So I like to think that as the two bullets pierced my body, as I collapsed onto the linoleum of my kitchen floor with a half-eaten granola bar clutched in my hand, as I lay immobile in a spreading puddle of my own blood, and yes, even as my heart stopped beating, that I still tried to do something to protect my daughter.

The reader wants to know: Did he die? Was his daughter okay? And what was he trying to protect his daughter from?

Review the sketch of your opening scene. Decide how you should end it to achieve maximum forward momentum. Steer clear of a “Had I but known” ending or a generic “Boy, was I surprised and terrified by what happened next” statement that could be tacked on to the end of any novel’s opening.

On Your Own: Write a Dramatic Opening

- Write the opening scene for your novel.

- Review your scene, and examine your choices:

- Does the first sentence set up the scene?

- What’s the out-of-whack event?

- Does the scene pose an unanswered question?

- In what tense is this scene told, and which character is the narrator? Are you happy with these choices?

- Have you dumped a load of unnecessary backstory into the opening?

- Revise, and move on.