Chapter 5

Innocent Suspects

“Everybody has something to conceal.”

—Sam Spade in Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon

“I’ve called you all together …” announces the great Hercule Poirot as he rearranges Staffordshire figurines on a marble mantle into perfect symmetry before turning his beady-eyed attention on the suspects gathered around in the drawing room. With great drama, he lays out the case against suspect number one, only to reveal his innocence. He does the same with suspect number two, and so on around the room until, somewhere around suspect number five Poirot spins around and confronts anew one of the earlier suspects and reveals him to be, ta-dah, the killer.

Modern mysteries are rarely so heavy-handed, but the basic bait-and-switch principle still applies. There’s a passel of suspects, each with a motive for murder, each with a secret or two. Attention moves from one suspect to the next until the villain is revealed. For the solution to surprise the reader—and credible surprise is what readers crave—then either the most obvious suspect is not the killer, or the crime is not what it appears to be.

How many suspects do you need? At least two (plus the true villain) will keep the reader guessing. More than five and it starts to feel like a parlor game.

DETERMINING THE SUSPECTS’ SECRETS

Create a cast of innocent suspects who have secrets. Secrets have the power to make characters look guilty or reveal their innocence.

A secret can be something the suspect doesn’t know. For instance, a suspect might not know that her husband was once married to the victim. Or a suspect might not be aware that she’s the prime beneficiary of her murdered aunt’s estate.

A secret can be something the suspect knows and lies about to cover up.

Or the secret can even be that the suspect doesn’t exist. A clever villain might plant evidence implicating someone who’s dead or whose identity was entirely fabricated.

Here are some examples of suspects’ secrets and lies:

| Secret | Lie |

|---|---|

A suspect is on the run from an abusive ex-boyfriend. | She lies about her true identity to keep her ex-boyfriend from finding her. |

A suspect was robbing a bank across town when the murder happened. | He says he was with his girlfriend at the time of the murder; he’s lying to avoid being arrested for the heist. |

A suspect thinks her brother is guilty. | She says her brother was with her at the time of the murder to protect him. |

MAKING INNOCENT SUSPECTS LOOK GUILTY

Virtually any character in your novel can be made to look suspicious. Here’s a rule of thumb that’s familiar to any mystery reader: The guiltier a character looks at the beginning of the story, the more likely he will turn out to be innocent.

Here are some devices that you can use to cast the shadow of guilt on innocent characters:

- Obvious motive: The character inherits the estate, or was having an affair with the victim’s husband, or was being blackmailed by the victim, or had been jilted by the victim.

- A vanishing act: The character is nowhere to be found when investigators come to question him after the murder.

- Stonewalling: The character can’t remember or refuses to tell the police where she was at the time of the murder.

- Contradictory behavior: A character who claims to be clueless about guns has an NRA membership card in his wallet.

- Eavesdropper: The character is overheard telling the victim, “Drop dead.”

- Enmity between the character and the victim: The two are cutthroat business rivals, were engaged in a nasty lawsuit, or are in love with the same person.

- Overeagerness to answer questions: The character goes to investigators and provides bushels of information that implicate others … but not all of it turns out to be true.

- Rotten rep: The character is known to be a swindler or a compulsive liar.

- Guilt by association: The character hangs out with other unsavory characters or is married to someone who hated the victim.

- Previously suspected: The character was questioned in a similar homicide investigation; someone else was convicted, but now investigators wonder.

- Previously convicted: The character was convicted of a similar crime, though he claims he was innocent.

- Skeletons in the closet: No one knows it, but the character was once a compulsive gambler, alcoholic, drug addict, pedophile, or embezzler.

- Cracks in the veneer: A flawlessly beautiful, kind, or generous character is seen kicking a dog, slapping a child, or grinding a delicate trinket under his heel.

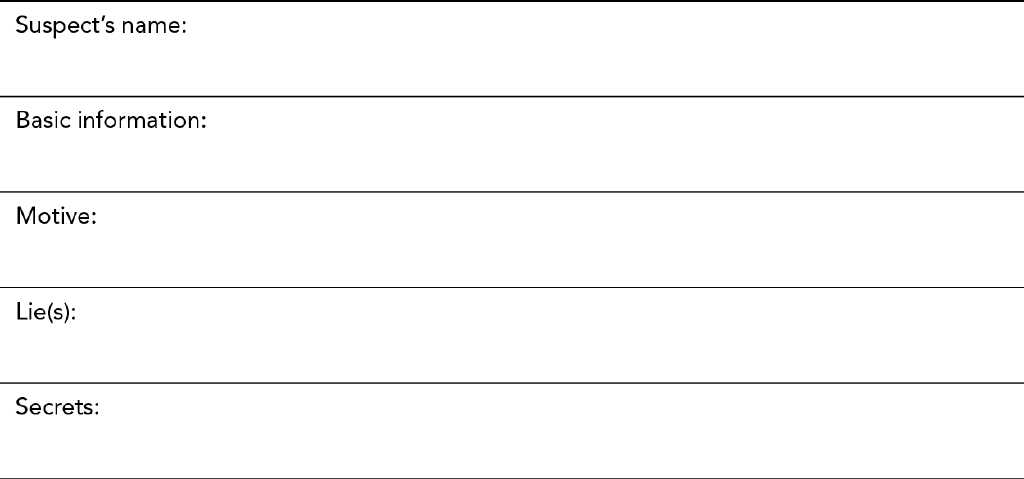

PLANNING A SUSPECT

A good way to prepare for bringing a suspect to life on the page is to create a thumbnail sketch. Use unexpected contrasts to keep your suspects from turning into clichés. A jealous, bleached-blond, Armani-wearing wife might once have been a Peace Corps volunteer who still sponsors Bolivian orphans. A rigid, controlling bank manager might love to share knock-knock jokes with his five-year-old daughter. Contrasts like these make characters feel human.

A thumbnail sketch of a suspect should include the following:

- Basic information: The suspect’s name, relationship to the victim, age, gender, any distinguishing physical characteristics, anything significant about his personality or past, a few telling details (something he owns or does, a favorite expression, etc.) that define him, and quirky contrasts to make him unique.

- Motive: Why this character might have committed the murder.

- Lie(s): The lie(s) this character tells.

- Secret(s): The secret that makes this character look guilty; the secret that demonstrates this character’s innocence.

Here’s an example of a thumbnail sketch of a suspect:

Crime scenario: Martha Collicott, a wealthy, elderly widow, is strangled in her bed.

Suspect: Terry Blaine

Thumbnail sketch:

Basic Information

He’s Martha’s nephew, twenty years old, unemployed, handsome, fair-haired college dropout; bright but an underachiever; was always Martha’s favorite nephew; drives a vintage Corvette and wears $200 sneakers; no regular address (says he’s “staying with friends”). He’s the only one who cried at Martha’s funeral.

Motive

He inherits Aunt Martha’s money.

Lie

He says he was at a friend’s house, alone, watching television at the time of the murder.

Secrets

Secret that makes him look guilty: Terry is a compulsive gambler, deeply in debt, and being threatened by loan sharks; he needs Aunt Martha’s money to save himself.

Secret that demonstrates innocence: Terry was dealing drugs at the time of the murder.

Now You Try: The Suspect’s Secrets (Worksheet 5.1)

For one innocent suspect in your novel, come up with the following:

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

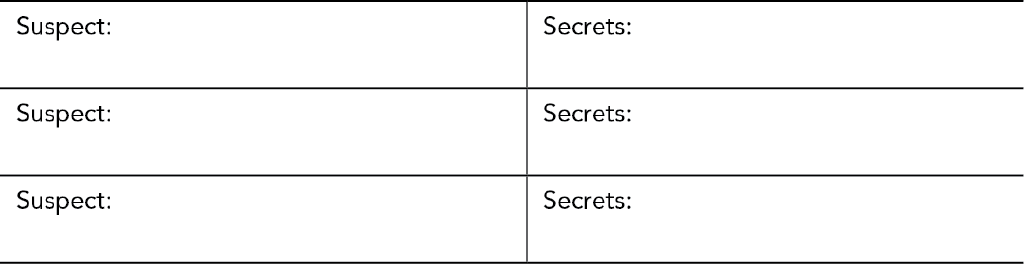

On Your Own: Innocent Suspects (Worksheet 5.2)

1. Watch a crime show such as NCIS or Law and Order. List the characters who become suspects, and note the secrets revealed about each one. Notice that sometimes the secret makes a suspect appear to be guilty; other times the secret demonstrates a suspect’s innocence.

2. Write a one-paragraph description of each innocent suspect in your novel.

3. Pick one innocent suspect in your novel. Brainstorm a list of possible secrets the suspect might be hiding.

4. Write a one-paragraph first-person monologue in the voice of the suspect you picked in step three, talking about the secret he’s hiding.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

Complete the Innocent Suspects section of the blueprint at the end of Part I.