Chapter 20

Writing Action

“I once started a detective story to make money—but I couldn’t get the murder to take place! At the end of three chapters I was still describing characters and the milieu, so I thought, this is not going to work. No corpse!”

—Mary McCarthy

Every mystery novel includes action sequences. An action sequence can be a getaway, a chase, or a desperate rush to catch a plane. It can be a confrontation: an attack, a fistfight, a gun battle, or a murder. Your character could get tied up and thrown in a car trunk or stumble through a forest in the dead of night while being tracked by attack dogs. To make it work, you have to write convincing physical action.

In the hands of a master, writing action seems simple. Take this passage from Lee Child’s The Enemy, in which Jack Reacher beats a hasty retreat:

I stood up and raced the last ten feet and hauled Marshall around to the passenger side and opened the door and crammed him into the front. Then I climbed right in over him and dumped myself into the driver’s seat. Hit that big red button and fired it up. Shoved it into gear and stamped on the gas so hard the acceleration slammed the door shut. Then I turned the lights full on and put my foot to the floor and charged. Summer would have been proud of me. I drove straight for the line of tanks. Two hundred yards. One hundred yards. I picked my spot and aimed carefully and burst through the gap between two main battle tanks doing more than eighty miles an hour.

This paragraph leaves the reader breathless. Take a minute to reread, analyzing Child’s word choice and sentence structure.

Here are some things that make it work:

- “And … and … and …”: A run-on sentence of short action statements connected by ands creates a sense of urgency and a repetitive drum-beat rhythm: I stood up and raced the last ten feet and hauled Marshall around to the passenger side and opened the door and crammed him in the front.

- Sentence fragments: Sentence fragments starting with the verb (Hit that red button…; Shoved it into gear…) suggest quick actions.

- Powerful action verbs: The sentences aren’t freighted with complex phrases, descriptions, adjectives, or adverbs; the verbs (stood, raced, hauled, crammed, climbed, dumped, hit, shoved) do all the heavy lifting.

- Actions and reactions: Just like in the real world, when something violent happens, there’s a reaction: … stamped on the gas so hard the acceleration slammed the door shut.

- A moment of introspection: A bit of internal dialogue (Summer would have been proud of me) allows the reader to catch a breath in the middle.

- The countdown: Two hundred yards. One hundred yards. I picked my spot and aimed carefully … Internal dialogue like this puts the reader in the middle of the action, moving forward, closing in.

I asked Lee Child to explain his approach to writing this action sequence. Here’s what he told me:

There’s a lot of visualization. I used to be a TV director, and all this stuff is choreographed in my head, like I’m watching a phantom screen.

Also, I try to pre-explain anything that would slow the scene in question. Much earlier in the book, I established that Humvees are low and wide inside, so it seemed okay that Reacher could be shown climbing over Marshall and diving for his own seat. And earlier in that Reacher/Marshall scene, I had established the big red button instead of a regular key. That was quasi-researched inasmuch as I’m pretty sure I read it somewhere. I think it’s accurate. But even if it’s not, it sounds right, which is 99 percent of my research process.

How many revisions did it take Lee Child to craft an action sequence of this quality? I nearly cried when he gave me his answer: “With climax pieces like that one, I always use the first draft. No revision at all. I’m usually in a zone by then, and that makes the first pass the best.”

What I wouldn’t give to get a ticket to whatever “zone” he’s talking about. For me, and for most writers I know, it takes quite a few rewrites to achieve action that’s this spare and effective.

Now You Try: Analyze Action (Worksheet 20.1)

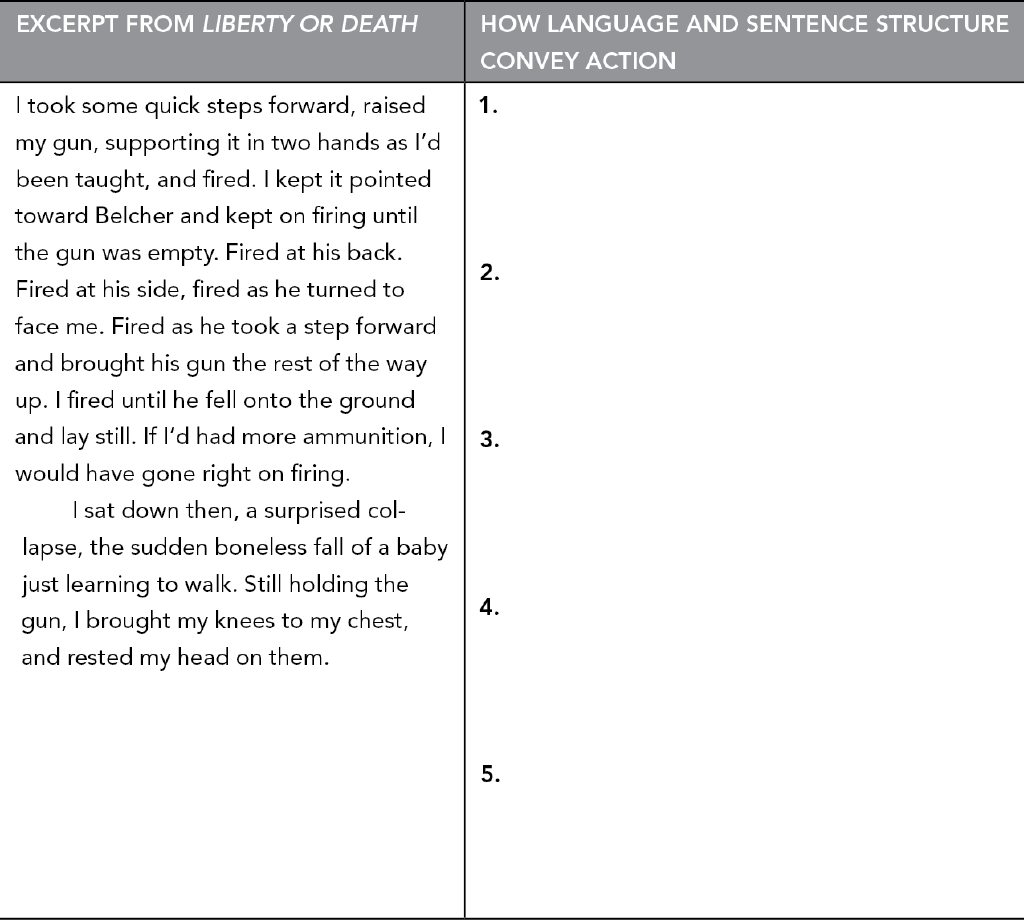

Read the following action sequence from Kate Flora’s Liberty or Death. List the ways Flora uses the language and sentence structure to convey action. Notice, also, how she conveys heroine Thea Kozak’s complete exhaustion, despite the action that’s going on.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

VISUALIZING IN ADVANCE

The first step in writing an action sequence is to visualize what you want to happen. Some people can visualize the whole scene from start to finish. Usually I can see what’s going to happen at the beginning and how it’s going to end, but the middle is a blur. I have to write my way into the action in spurts.

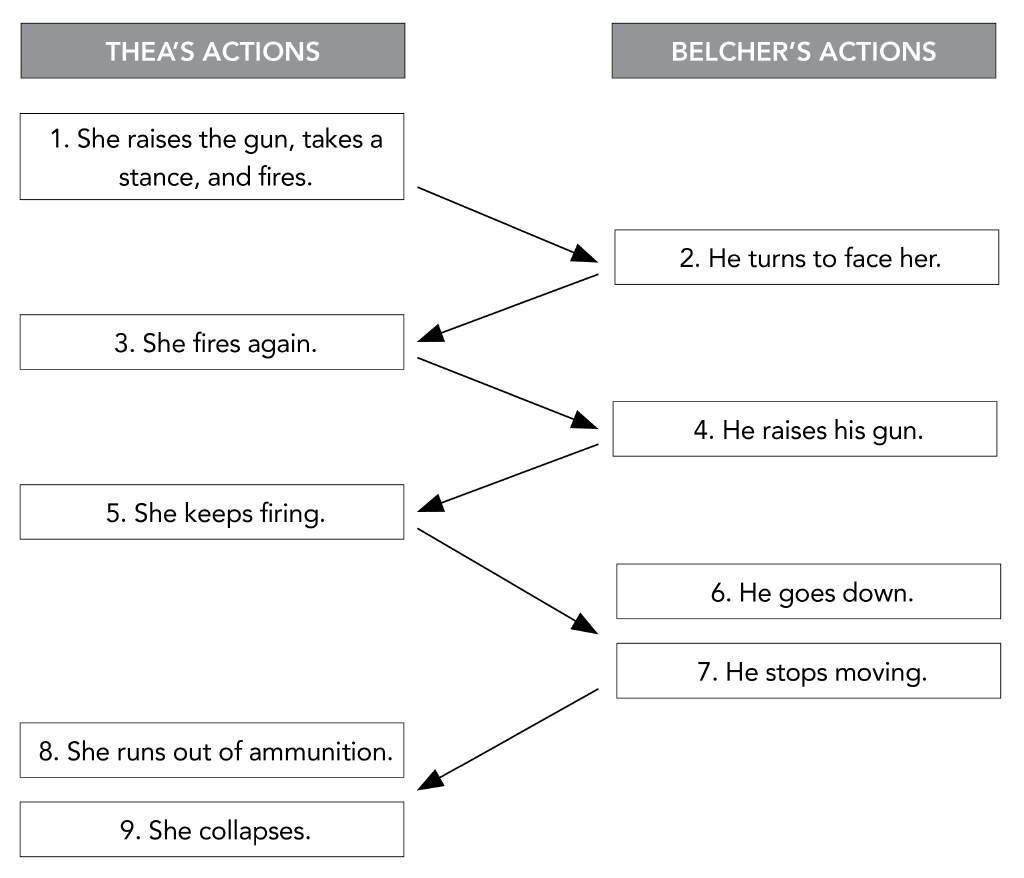

Action sequences are about action and reaction, action and response. A useful approach is to map out an action before you write it: choreograph it in your head, and then list the main points:

- where the action takes place

- what happens

- what the characters do in relationship to one another, step by step

For example, here’s how Flora’s action sequence might be mapped out:

- Who: Thea Kozak and Roy Belcher

- Where: In a field behind the house

- What happens: Thea shoots Belcher

Mapping out the action before dramatizing it in writing helps you visualize what your characters are going to do in the scene.

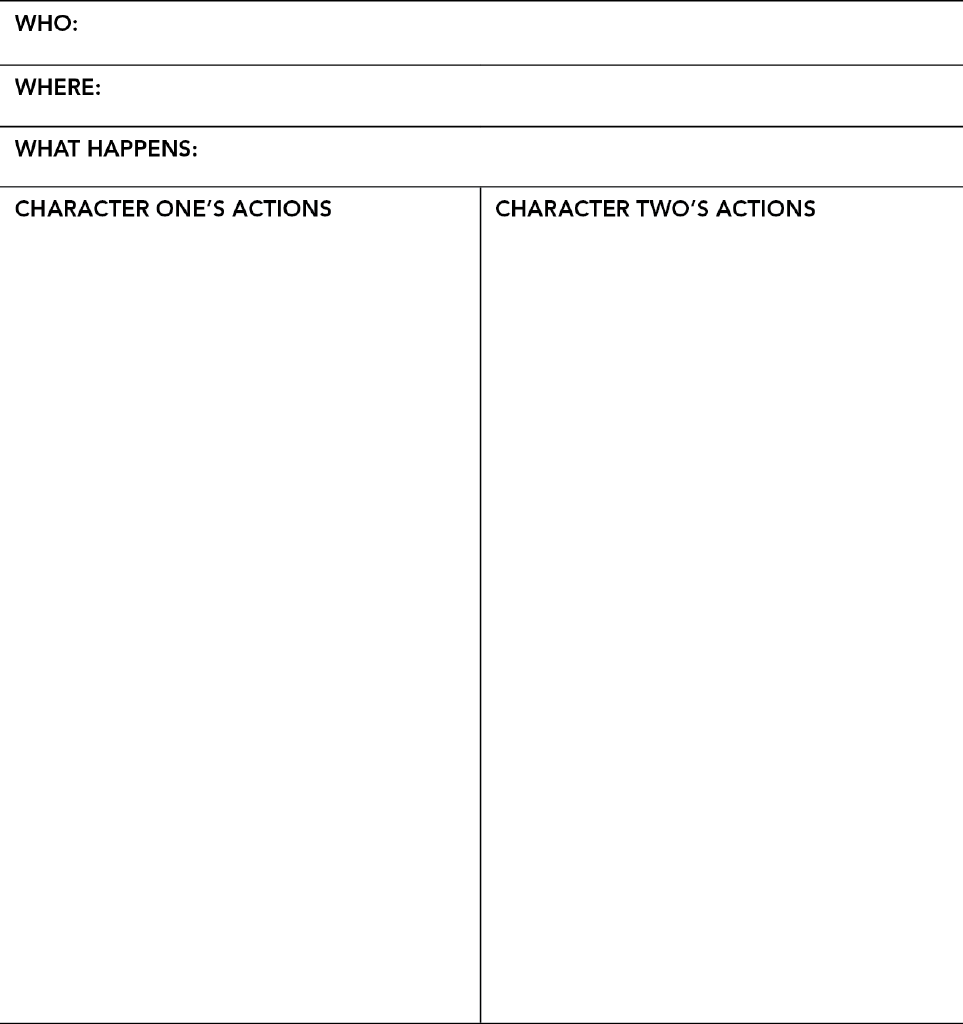

Now You Try: Mapping out the Action (Worksheet 20.2)

- Find a two-character action sequence from a television show or movie.

- Play one minute of this scene with the sound turned off, and replay it as many times as necessary to map out the sequence below.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

SPEEDING UP ACTION AND SLOWING IT DOWN

Sometimes you want to speed up an action sequence and compact time. Other times you want to slow things down and make it feel surreal. Both techniques can be riveting.

In Lee Child’s tank scene from The Enemy, he speeds up the action. He keeps the camera zoomed in and presents the action at a rapid-fire pace. His goal is to get his character the hell out of Dodge and leave the reader panting for breath.

In Kate Flora’s shoot-out, she slows down the action. Her character is exhausted, on the brink of collapse. By pulling the camera back and slowing down the sequence, she gives the sequence a dreamlike quality.

Here’s a guide for modulating the pace of an action sequence:

| To Speed Up the Action | To Slow Down the Action |

|---|---|

Focus, and pull the camera in close. Limit extraneous detail. Keep sentences short and direct; drop the pronouns. Minimize internal dialogue. | Pull the camera back. Provide descriptive detail. Use longer, more complex sentences. Convey some introspection. |

MAKING ACTION BELIEVABLE

A successful action sequence must be believable. Lapses in logic distract the reader from the drama you’re trying to create.

If your action has guns in it, make sure you know what you’re talking about. Are the characters using handguns, rifles, or shotguns? If they’re using handguns, are they revolvers or a semiautomatic pistols? I don’t know Glocks from Mausers, but if you’re writing about them, you should. You need to know how to load, aim, and fire, what the recoil feels like, what happens to the spent shell casing (if there is one), whether the gun gets hot, and, most important, whether your character could handle that particular weapon.

Kate Flora told me how she learned about guns:

One day I was sitting in a police station talking with an officer who was a good friend. When I mentioned that I had never shot a handgun, he looked at his watch, shook his head, and said, “We’ll have to fix that.”

He then took me to a shooting range in the basement of the department and walked me through the process of shooting. He taught me about how to hold the gun and the proper stance for shooting and bracing for recoil, and then I squeezed the trigger (not pulled) and everything I’d ever seen on TV or read about guns was literally blown away.

It was a big gun with a big jump and a flash of flame and a thunderous noise followed by a gust of smoke. The air filled with the smell of exploding gunpowder, the ejected shell flying back at me, and it left me stunned, shaken, and rubber-limbed. Shooting a gun is not a small thing.

If guns play a major role in your book and you don’t know a friendly cop who will take you to a firing range, take a firearms class.

Writing a physical fight requires some know-how, too. If you’re like me and you’ve survived this long by fleeing rather than fighting, you’ll need to do some research. There are many books and handbooks on the subject. For instance, the U.S. Army has an official training manual on hand-to-hand combat that covers different moves such as choke holds, throws, kicks, and blocks. Watch a hand-to-hand combat video, or, better yet, take a self-defense class—many community police departments sponsor them.

Get the medical detail in your action sequence correct. Ask any doctor, and you’ll quickly discover that a single blow to the head is almost never fatal. Rarely is death instantaneous from a stab or gunshot wound either. The pool of blood around a corpse’s head shouldn’t grow—dead men don’t bleed.

A good source for this kind of information is Forensics: A Guide for Writers by D.P. Lyle, M.D. (Writer’s Digest Books).

So do your homework, get the details right, but don’t show off. One guaranteed way to deflate a gun battle is to dump everything you’ve learned about semiautomatic pistols into the middle of it.

KILLING ACTION WITH CLINICAL DETAIL

You can also kill an action sequence by describing the action with excruciating detail. Here’s an example of what not to do:

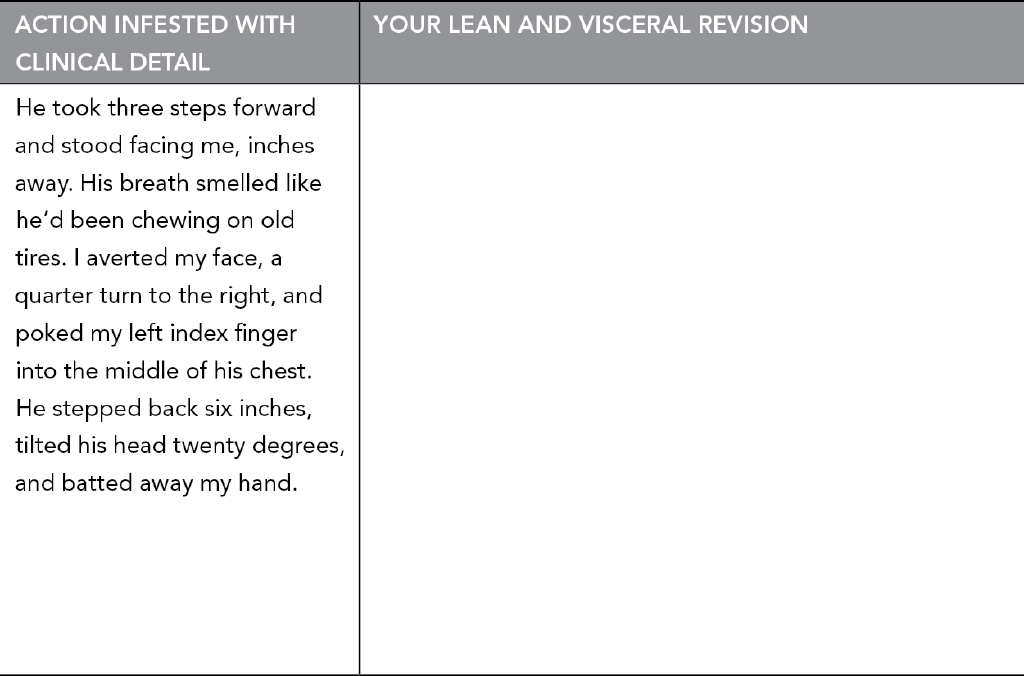

He took three steps forward and stood facing me, inches away. His breath smelled like he’d been chewing on old tires. I averted my face a quarter turn to the right and poked my left index finger into the middle of his chest. He stepped back six inches, tilted his head twenty degrees, and batted away my hand.

This is an exaggeration, but you get the idea. The only detail I like in this passage is the bit about bad breath and the verb poked. Red flags should go up in your mind if you start writing about quarters and halves, left and right, inches and degrees. Yes, these details describe action, but all that measurement and specificity bring it to its knees.

Here’s an example from my novel Never Tell a Lie. Note how much leaner the description is, and yet the passage is still easy to visualize.

Ivy dropped the receiver, grabbed the teakettle from the stove and brought it down as hard as she could on the woman’s head. Then she raced into the mudroom. The spare key was there, hanging from the hook by the door.

She felt movement behind her. Hurry!

She jammed the key in the lock, turned it. She had the door barely open when the woman’s forearm clamped around her neck. Before Ivy could resist, she was shoved hard against the door, slamming it shut. The sound seemed to explode in her skull

Something stuck into Ivy’s side—the knifepoint, she realized, pricking through the sweatshirt and into her skin. She tried to pull away. Winded and breathing heavily, the woman wrapped her arm more tightly around Ivy’s neck and twisted the knife tip against Ivy’s ribs.

Ivy’s head throbbed, and patterns of yellow and black kaleidoscoped in front of her tightly shut eyes.

“Lock the door and give me the key,” the woman said, her voice low.

Ivy hunched her back, struggling to make a safe hollow for the baby. She screamed as the knife cut into her skin. She tried to angle her body to keep the baby from being crushed inside her, trying to ease the pressure of the knifepoint.

In an action sequence, less is more. Provide just enough detail to show the reader what’s going on, using simple sentences and powerful verbs. Establish crucial details in advance. Trust the reader to fill in what you judiciously leave out.

Now You Try: Revise to Eliminate Clinical Detail (Worksheet 20.3)

Rewrite this action sequence, getting rid of the clinical detail:

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

AVOIDING DETOURS DURING ACTION: ESTABLISHING IN ADVANCE

If you find yourself taking a pause in the middle of an action sequence to explain something to the reader, be aware that you are slowing the forward momentum. For instance, suppose your character is being chased along the edge of a cliff and you describe to the readers how high it is, how the waves crash on jagged rocks a hundred feet below. If you don’t, you reason, how will they appreciate how dangerous this is? They won’t. But ask yourself: Is this the best place to insert the description?

Don’t dump explanation into an action sequence unless you want to modulate the forward momentum. Instead, establish this setting earlier. Have your character walk his dog there while he’s thinking through the clues or searching for evidence. Describe the breathtaking view from this spot, or have his dog scrabble back from the edge. Then, later in the novel, when you get to the action sequence at that cliff’s edge, you can let ’er rip.

Now You Try: Write an Action Sequence

Dramatize the action sequence you mapped out earlier in this chapter. Then, follow these steps:

- Underline all your verbs. Are they strong enough? Replace the ones you feel need strengthening.

- Examine your sentence structure. Is it appropriate to the feeling you’re trying to convey—simple and straightforward if you want the scene to move fast, or more complex if you want it to slow down?

- Are you writing with the camera as close as you need it to be? Remember: Zooming the camera in heightens intensity and speeds up action; drawing back gives the scene a dreamlike feel and slows things down.

- Is the writing clear and lean?

- Is there anything in this scene that needs to be established earlier in the novel? Make a note in your outline to establish that information where you think it belongs.

On Your Own: Making Action

- Pick a novel you’ve read that’s filled with a lot of action. If you can’t recall one, pick anything by Lee Child or Lisa Scottoline. Skim the last third for an action sequence. Read and analyze it. What’s the overall effect of the scene, and how does the writer achieve it?

- Plan to research certain topics for the action sequences in your book. For instance, if you know your plot involves guns or hand-to-hand combat, your plan might include taking a firearms or self-defense class.

- Write action sequences, mapping them out in advance if you like. Use this checklist to guide your work:

___ Use powerful verbs.

___ Use active voice.

___ Use simple sentences.

___ Keep introspection to a minimum unless you’re deliberately slowing down the action.

___ Keep description to a minimum unless you’re deliberately slowing down the action.

___ Make sure actions have reactions.

___ Establish in advance anything that will bog down the scene.