Chapter 9

Staking Out the Plot

“An outline is crucial. It saves so much time. When you write suspense, you have to know where you’re going because you have to drop little hints along the way. With the outline, I always know where the story is going.

—John Grisham

“I do a very minimal synopsis before I start, and I know where I end up, I know sort of stations along the way, but I give myself freedom to kind of just discover things as I go along.”

—Louis Bayard

“I just dive in and hope the book comes out at the other end. And as I get to the character, slowly the plot develops like a Polaroid.”

—Tana French

A great mystery plot is like a thrilling ride on a roller coaster. The cars go shooting out of the starting gate. Then there’s a slow, steep climb before a deep plunge. There’s a brief respite before the ride gathers speed, going fast and then faster, rising to a hairpin turn and an even steeper drop. You barely catch your breath and the ride gains speed again, rising to yet another twist and plunge. There’s a final twist and a heart-stopping plunge, and then you coast back to the platform, exhilarated and ready to ride again.

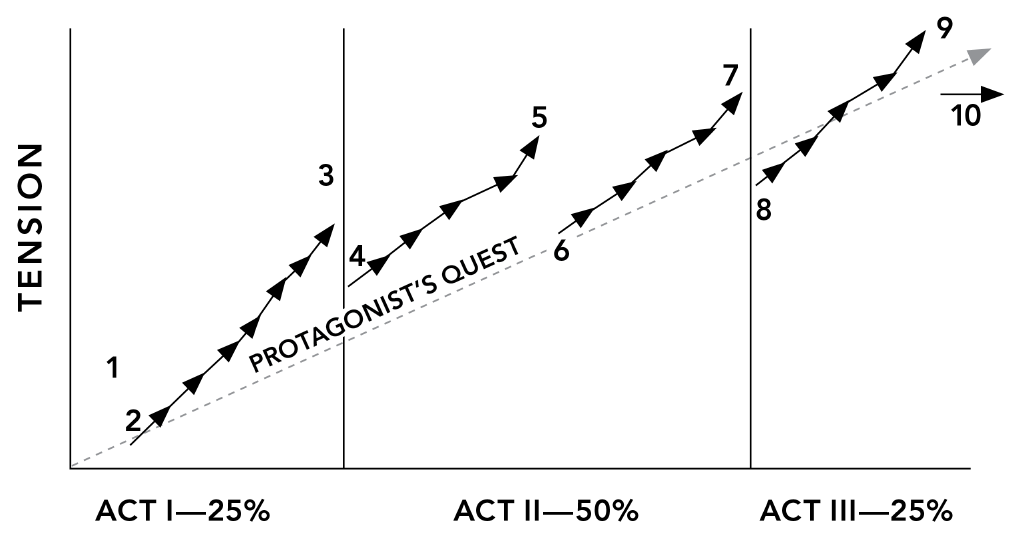

In more mundane terms, a mystery novel is comprised of groupings of scenes that can be thought of as acts, sandwiched between a dramatic opening that sets up the novel at the beginning and a coda that explains all at the end.

During each act, tension rises to dramatic climaxes and plot twists. At or near the end of the last act, there’s a slam-bang dramatic finale in which the protagonist is in jeopardy and the truth revealed. At the end, loose ends are tied up and the world is safe from evil once more.

THE SHAPE OF A MYSTERY PLOT

The graphic below shows the big picture: the typical three-act structure of a mystery novel.

Tension rises as the story moves forward through three acts. The short arrows are meant to suggest that each act is made up of scenes—though in fact there are many more scenes than are shown, and tension rises and falls among them. The dashed line represents the protagonist’s quest.

Briefly, this is how a plot might unfold over the three acts:

Act I

1. The act begins with a dramatic opening, the incident that sets the story in motion.

2. The story continues: The protagonist, the main characters, and the setting are developed along with the main problem of the story and the initial goal.

3. The act ends with a major plot twist, usually a revelation and a reversal that sets back or derails the investigation.

Act II

4. Throughout the act, complications mount (roadblocks, more danger, the stakes grow higher and more personal); secrets are revealed; and past events are revealed.

5. At the midpoint, a major plot twist occurs.

6. Through the second half, there are more complications, the stakes rise, and the clock ticks.

7. The act ends with another major reversal; the protagonist hits the wall and seems utterly defeated.

Act III

8. The protagonist rebounds from the reversal at the end of Act II.

9. The story builds to a dramatic climax during which the protagonist faces off against the villain and triumphs.

10. A final few scenes serve as a coda, tidying up loose ends and bringing the story to a close.

WELDING CHARACTER TO PLOT: PLAGUING THE PROTAGONIST

The protagonist’s quest to find the killer unifies a mystery novel. In the plot diagram, this quest is represented by the dashed line. In Act I the protagonist’s goal is set, though the goal might shift before the final shoes drop. What keeps the reader hooked are all the roadblocks and setbacks the sleuth has to overcome and how the stakes increase as the story moves forward.

Drama works in direct proportion to how miserable you make your protagonist. Here are some ways to plague him:

- Discomfort: The hungrier, thirstier, colder (or hotter), achier, and generally more pissed off he becomes, the more heroic the quest. Give him a scraped knee, sprained ankle, dislocated finger, bloody nose, broken arm, or gunshot wound, and show how he pushes past pain and disability in order to continue his pursuit. Make sure the reader knows he feels the pain, but be careful about letting him bitch and moan too much about it—no one likes a whiny hero.

- Inner demons: If you’re going to throw your character into a snake-filled pit, establish beforehand that she’s terrified of snakes. If your character is an alcoholic trying to stop drinking, make her quest for the killer take her into bars.

- Mishaps: Throw obstacles at your character to slow him down. His car can break down, or he can be set upon by thugs who turn out to be protecting the villain, or his car can roll over and end up in a ditch after being nudged off the highway by a semi. Maybe your character learns something damaging about one of the suspects, but she can’t get anyone to listen to her. After each setback, the sleuth comes back stronger and more determined.

- Modulating the misery: Begin with minor woes and build as the story progresses to its final climax. From time to time, things should improve. Then, just when it looks as if your protagonist is out of the woods, let the next disaster strike.

- Raising the stakes and making it personal: On top of all those plagues, keep raising the stakes so your protagonist’s need to bring the killer to justice gets stronger. For example, an innocent character is about to be convicted of the crime. Or maybe the protagonist or a loved one is in jeopardy. Or a villain threatens to escalate his attacks, and your protagonist is the only one who can stop him.

Reaching the end goal should feel heroic, worth all the pain and misery your protagonist had to overcome along the way.

Now You Try: Your Sleuth’s Quest (Worksheet 9.1)

In a sentence or two, describe your sleuth’s quest. What does she want or need to achieve before the novel ends? Where does the quest start, and where does it end? Then make a list of plagues—potential setbacks, roadblocks, and other forms of misery you might throw in her way. Finally, decide how you’re going to raise the stakes.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

A DRAMATIC OPENING: THE SETUP

Open your mystery novel with a dramatic scene in which something out of the ordinary happens. It might be a murder or just some out-of-whack event with an element of mystery to it.

Your novel might open with the murder itself. Or it might begin with your protagonist discovering that someone has been murdered. Or it might start with an event that happened years before the main story begins.

Your book has to start in an exciting or intriguing way by posing an unanswered question that provides a narrative hook that pulls the reader forward. You don’t have to have a body drop in the first chapter. And you usually can’t solve the problem of a flat, uninspired opening by inserting a prologue that flashes forward to the murder, followed by a chapter one that takes place earlier.

Here are some examples of award-winning bestsellers in which the opening scene sets up the book and pulls the reader forward without a murder:

Out-of-whack-event: A baby is found abandoned on the steps of a church. (In the Bleak Midwinter, Julia Spencer-Fleming)

Unanswered question: Who left the baby on the church steps, and what happened to the baby’s mother?

Out-of-whack-event: A criminal defense attorney meets her new client—a woman accused of killing her cop boyfriend. The woman extends a hand and says, “Pleased to meet you, I’m your twin.” (Mistaken Identity, Lisa Scottoline)

Unanswered question: Is this woman the defense attorney’s twin, and is she a murderer?

Out-of-whack-event: PI Bill Smith receives a late-night telephone call from the NYPD, who is holding his fifteen-year-old nephew Gary. (Winter and Night, S.J. Rozan)

Unanswered question: Why would Gary ask for Smith? Smith hasn’t seen his nephew for years and is estranged from Gary’s parents.

A warning: Don’t allow your opening scene to steal your book’s thunder. It’s tempting to write something that foreshadows the big secret, but keep in mind that in doing so you might weaken the reveal at the end.

So pick your opening gambit, and examine it with a critical eye. Be sure it sets up your novel, propels the reader forward, but doesn’t rob your story of potential surprise by revealing too much too soon.

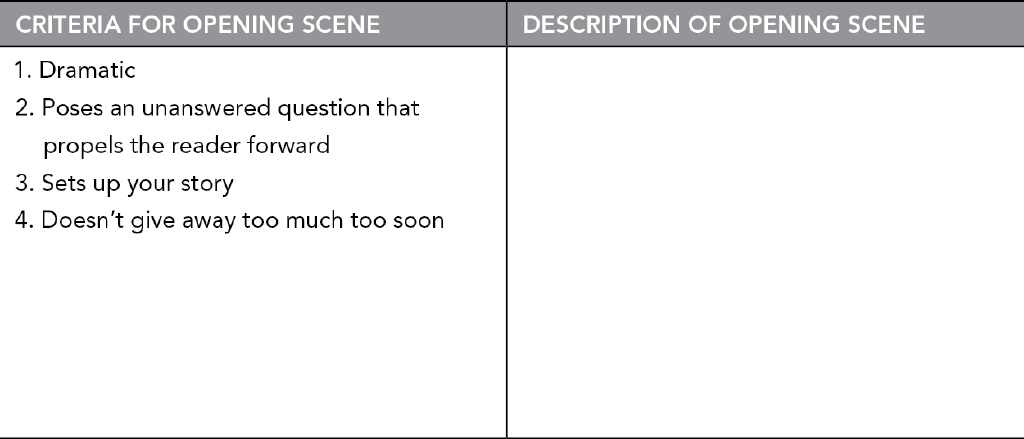

Now You Try: Find Your Opening Scene (Worksheet 9.2)

Review your crime scenario and your sleuth’s quest. Think about where you want your story to start, and find a dramatic opening scene. Is it the crime itself? The start of the investigation? Or is it some other dramatic prelude to your story?

Write a one-paragraph description of your opening scene. Be sure your scene meets the criteria shown below.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

PLOT TWISTS

The plot twist is the most basic ingredient in a mystery. The unanswered question posed at the end of your opening scene is your novel’s first plot twist. A twist might raise the stakes, exonerate one suspect or implicate another, or completely change the reader’s understanding of the crime or the nature of one of the main characters. A major plot twist changes the direction—or the urgency of the investigation.

Plot twists should be surprising and credible at the same time. If the reader sees a plot twist coming, it’s not a twist.

As you develop your plot, keep asking: What does the reader expect to happen next? What could happen instead? Brainstorm possibilities, and go in an unexpected but plausible direction.

Here are just a few of the many ways to twist your plot:

- A witness is discredited.

- A witness recants his story.

- A witness disappears.

- The victim isn’t dead after all.

- New evidence is discovered implicating a new suspect.

- New evidence is discovered implicating the sleuth.

- The true implications of evidence that was previously misinterpreted are revealed.

- Evidence is discredited.

- Evidence disappears.

- A secret in a victim’s past is revealed.

- A secret in a suspect’s past is revealed.

- A threatening message is received.

- Another victim dies.

- A witness dies.

- The prime suspect dies.

- The sleuth is attacked.

- The sleuth is arrested.

At the end of each act, plan a dramatic climax that provides an ending to the story so far and a major plot twist that propels the reader forward to the next act.

THE FINAL CLIMAX AND CODA

Most mystery novels have a final climactic action scene fraught with mortal danger, during which the protagonist and the villain duke it out. That scene contains the payoff for the entire novel. It’s one of the most important scenes in your book—second only to the dramatic opening.

After the climax, there’s often a coda, a more contemplative scene in which all is explained. You can write three hundred pages of a great book, but if the final twenty don’t fulfill the promise, it’s a washout.

The ending should be plausible, surprising, and, most important, satisfying. In many mysteries, the protagonist triumphs, the villain is defeated, and justice is served. Don’t feel bound by convention if a more unusual ending suits your story, but whatever you do, be sure that in the end it is crystal clear whodunit, why, and how. Readers should never be left scratching their heads.

PAGES, SCENES, CHAPTERS, AND ACTS

Scenes are the building blocks of a mystery novel. A scene contains the dramatic action of an event that occurs within a single time frame, in a single place, narrated throughout by one of the characters. When the time or place or narrator changes, this calls for a new scene. Every scene in a mystery novel should have a payoff—something that happens or changes to propel the story forward.

There’s no ideal scene length. Several scenes may be grouped into a chapter, or a chapter may be one long scene, or a really long scene can be broken up across several chapters.

The acts in your novel are dramatic structures; they end with major turning points. While the text usually looks like the end of any chapter, it should feel to the reader as if a major part of your story has ended—tension has risen to a crescendo and a major plot twist has been introduced. The beginning of the next chapter is the beginning of the next act, and it feels as if the momentum is starting to build all over again: The tension has ratcheted down, and the characters take time to digest the implications of the latest plot twist.

The dramatic opening and Act I generally comprise the first quarter of the novel. Act II makes up roughly half of your total pages. Act III is the final quarter. Here’s an example of how a three-hundred-page novel might lay out:

| # Pages | # Scenes | # Chapters | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Act I | 75 | 11 | 9 |

| Act II | 150 | 24 | 16 |

| Act III | 75 | 13 | 10 |

| Total | 300 | 48 | 35 |

Now You Try: Analyze Plot Structure (Worksheet 9.3)

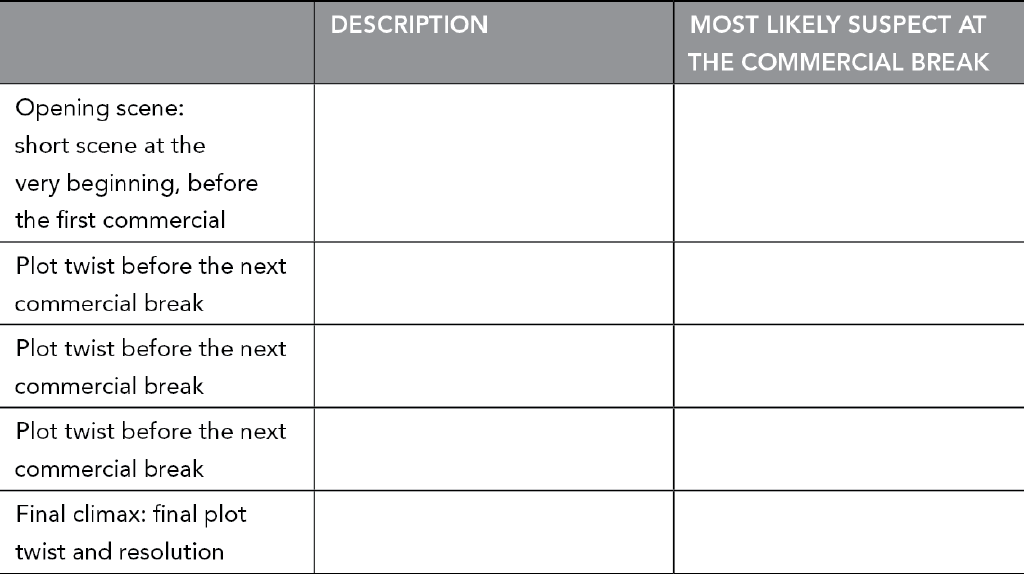

To get the hang of how a mystery works, analyze the plot of a standard, one-hour crime show. These tend to be structured like mystery novels. They begin with a dramatic opening, and the commercial breaks impose a four-part structure. Usually there’s a plot twist before each commercial. Often they end after the final dramatic scene, dispensing with a coda.

Watch a show and analyze the structure of the plot by filling out this scorecard:

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

SUBPLOTS

Mysteries have secondary plots interwoven with the main one. Subplots can make the novel more complex and interesting and the characters more three-dimensional. They can also provide the reader with a breather or some comic relief from the ongoing, increasing tension of the main plot.

Subplots can be heavy or lightweight, tragic or comic, but they should always be integral to the novel, not slapped on. They should tie directly to the main plot, echo its themes, complicate the crime investigation, or provide the main character an opportunity to address inner demons.

Here are some different kinds of subplots:

- A romance: The main character becomes romantically involved. Now we have a character the protagonist cares about, someone who can be put in jeopardy, which ratchets up the stakes.

- Trials and tribulations of the main character’s friends and family: Colorful relatives or friends can provide comic relief or complicate the protagonist’s quest in interesting ways.

- Health issues: A character attempts to lose weight or get pregnant, deal with a disability, or fight a life-threatening disease.

- Challenges of the protagonist’s day job: There are many ways to use the drama of the character’s day job to complicate the story; for example, the character has an ongoing rivalry with a co-worker, deals with a demanding boss, tangles with bureaucracy, or gets fired.

- Investigation of another, apparently unrelated crime: A major plot twist occurs when this second crime ties into the main one.

- Unresolved event in a character’s past: The narrative seesaws back and forth between the present action and some unresolved past event. The ending of the book is doubly satisfying when the crime is solved and a past wrong is righted.

How many subplots does your story need? There should be at least one, and some novels can handle as many as five or six. While you should resolve the main plot at the end of the novel, a subplot can be left hanging—which is especially useful if you’re writing a series. For instance, you can bring a romantic subplot to the brink of intimacy and then leave the reader panting to read the next book.

TO OUTLINE OR NOT TO OUTLINE

Is a detailed scene outline essential or a waste of time? Some writers can’t start writing without one. Others say outlines are stifling and dry up their creative juices, preventing their characters from “taking over.”

I’ve written books from detailed outlines and books from nothing but a whiff of an idea, and while the writing process is very different, I can’t discern a difference in terms of final quality or overall writing time. When I do write an outline, it’s a spare, dry working document, pure and simple.

Here’s an example of the outline of the first scenes in my novel There Was an Old Woman.

| Scene | Narrator | Setting/plot points in There Was an Old Woman | Time Line |

|---|---|---|---|

1 | Mina | At home reading obits. Ambulance arrives for Mrs. Ferrante next door. Mrs. Ferrante asks her to “call Ginger” and “don’t let him in until I’m gone.” | DAY 1: Friday |

2 | Evie | At Empire State Building, retrieving B52 Bomber engine from elevator shaft. Gets call from sister, Ginger, which she doesn’t answer. | |

3 | Evie | At historical society, bringing back engine. Gets message from Ginger: Mom’s in the hospital. | |

4 | Evie | In Evie’s office. Takes Ginger’s call; they argue. “It’s your turn”; agrees to go home and deal with Mom. | |

5 | Evie | Goes to Mom’s. Stops at convenience store and reconnects with Finn. Sees house: it’s a hoarder’s nest, and her mother never was a hoarder. | DAY 2: Saturday |

6 | Evie | At home, sifting through the mess: cat food cans (her mother has no cats), empty liquor bottles (Mom’s an alcoholic); broken bedroom window. |

Put in as much or as little detail as you need. Consider including these elements:

- sequential scene numbers (you can chunk scenes into chapters later)

- the viewpoint character (if you have more than one narrator)

- the setting

- the characters in the scene

- events and major plot points

- the date or day of the week and the time of day

An outline like this is useful when you start writing. It keeps your place, helps you see the big picture, keeps track of time elapsed, and provides scaffolding on which to hang your story. It’s also easy to revise—you can move whole clumps of scenes from one place to another with a quick cut and paste.

Don’t feel tethered to your outline. Consider it a starting point. Treat it as a working document, and revise it as you write to reflect your current draft.

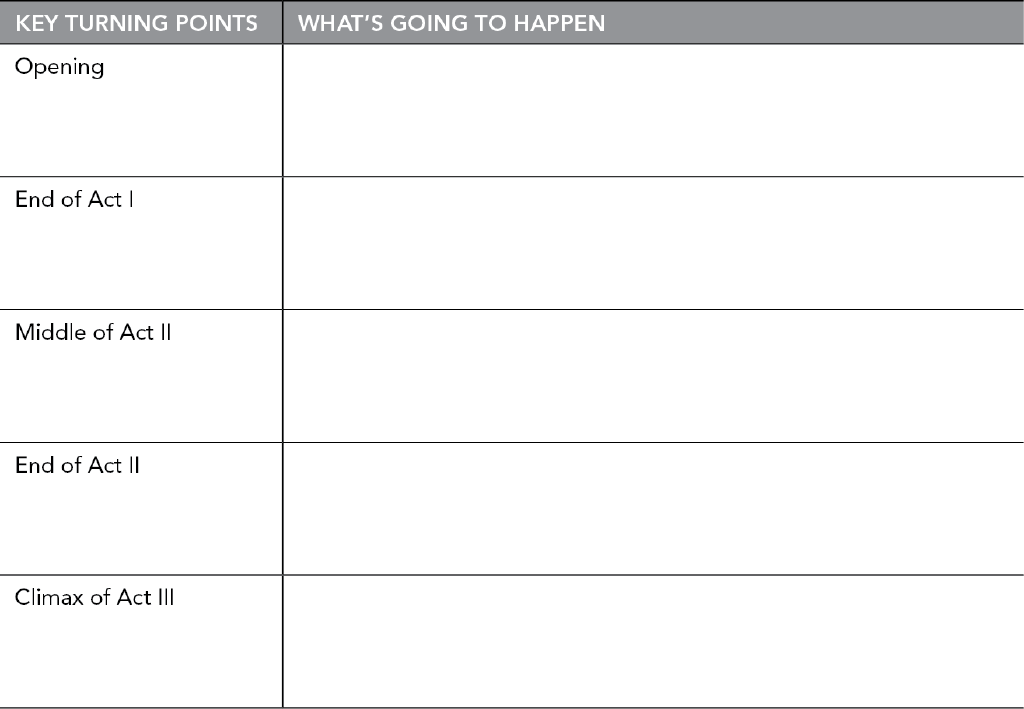

Now You Try: Outline the Main Turning Points (Worksheet 9.4)

While outlining the entire book in advance may seem daunting, mapping out the turning points is a good planning exercise. Briefly describe what’s going to happen at a few key moments in your book.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

WRITING A BEFORE-THE-FACT SYNOPSIS

In addition to (or instead of) an outline, you may want to write a before-the-fact synopsis of your book. As its name suggests, this synopsis is written before you start writing. It introduces the characters and the backdrop, and tells the story dramatically from start to finish. Here’s the beginning of a before-the-fact synopsis I wrote for There Was an Old Woman.

There Was an Old Woman [working title] tells the story of two women, one young and one old, who connect across generations in spite of the fact that, or perhaps because, they are not related.

Eighty-nine-year-old Wilhelmina “Mina” Yetner lives alone in the bungalow house where she grew up, in Taft Park in the Bronx, accompanied by her cat and surrounded by relics of her family’s past. Her father built her house in the 1910s to replace even tinier summer cottages, reserving the prime river view of the Manhattan skyline and the Empire State Building for his own house. Mina’s first job was as a secretary in the Empire State Building, and she was working there in 1945 when a B-52 bomber crashed into it. She’s the last living survivor of the fire that ensued.

Thirty-year-old Evie Ferrante grew up next door to Mina. She’s the daughter of Mina’s neighbor and a curator at a New York historical society. She lives in Brooklyn and is mounting her first solo-curated exhibition on historic NYC fires, including the Empire State Building fire after the plane crashed into it.

The book opens as Mina’s neighbor, Sandra Ferrante (Evie’s mother), a longtime alcoholic, is carried out of her house. She begs Mina to “call Ginger” (her daughter) and tell her, “Don’t let him in until I’m gone.”

This synopsis goes on for fifteen pages, summarizing the events of a three-hundred-page novel. A synopsis like this can be shown to an editor or agent. In fact, some publishers require authors to submit a synopsis as the first deliverable of a book contract.

Writing this kind of synopsis makes you think through all the plot twists and turns and articulate how one part of the story connects to the next. Once I’ve written a thorough synopsis, I find I’m less likely to write myself into a corner.

MAPPING CHARACTER TIME LINES

Every character in your book had a life before your book opens. Some of their past experiences were shared, and some were not. Some past experiences matter to the plot you’re writing. Some provide insight into why those characters do what they do in your novel.

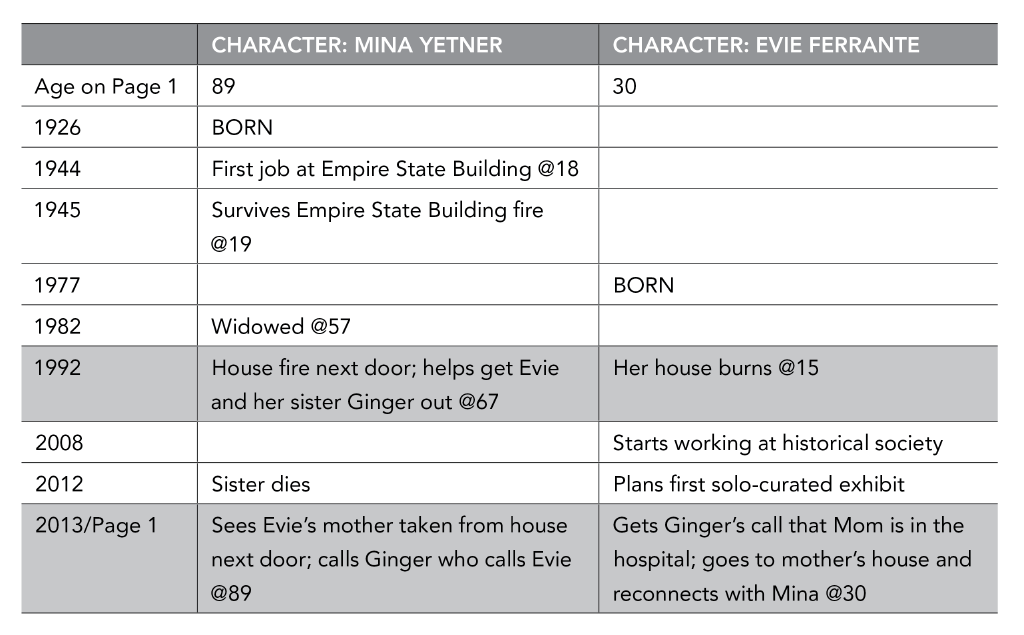

A multiple character time line can help you keep track of your characters’ most important past experiences, those that are critical to your story. Here’s the time line I put together when I was writing There Was an Old Woman.

The shaded rows indicate Mina’s and Evie’s shared experiences that are pivotal to my plot, leading up to the book’s opening.

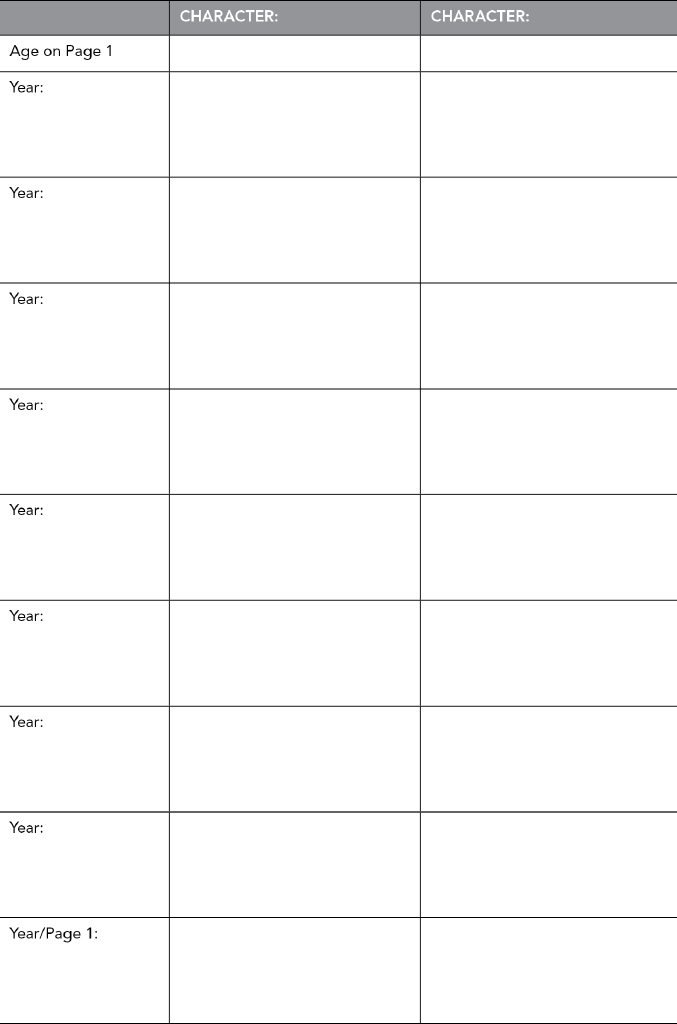

Now You Try: Map a Multiple-Character Time Line (Worksheet 9.5)

Choose two major characters in your book, and list events from their pasts in chronological order; shade the rows for events they experienced together.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

On Your Own: Staking Out Your Plot

Outline your story. Remember that you don’t have to outline every single scene in your novel before you start writing; you can do some detailed planning at the outset, write some scenes or chapters, then return to planning, and so on. This approach can be less overwhelming than outlining the entire plot before moving on.

- Create an outline that includes the following:

- the opening scene (the out-of-whack event)

- the rest of the scenes in Act I (Remember: every scene should have a payoff that moves the story forward.)

- the final scene in Act I, which contains a dramatic climax and plot twist

- a brief summary of what happens in Act II, plus a description of the climax and major plot twist

- a brief summary of what happens in Act III, plus a description of the climax and major plot twist

- the solution: whodunit and why

- After you’ve written the scenes in one act, outline the scenes in the next act. While you’re at it, revise the outline to reflect what you actually wrote.

- Repeat step two until you’ve finished the book.

Write a before-the-fact synopsis. Start small, and then add on.

- Write a one-paragraph synopsis that contains a dramatic summary of your novel. Include at least a summary of the dramatic opening, the crime, the investigation, and the solution.

- Expand the synopsis to one page, adding a summary of each act and the major plot twists.

- Expand it again, adding subplots.

- Keep expanding until everything in your head is down on paper.

Complete the Plot section of the blueprint at the end of Part I.