Chapter 19

Writing Suspense

“A character who unknowingly carries a bomb around as if it were an ordinary package is bound to work up great suspense in the audience.”

—Alfred Hitchcock

Suspense happens when a scene becomes charged with anticipation. It’s the possibility of what might happen that keeps readers on the edge of their chairs.

Think of the classic suspense scene in the Alfred Hitchcock movie Suspicion. The Joan Fontaine character believes that her charming husband, played by Cary Grant, is an embezzler and a murderer who is going to kill her. There’s a long shot as Grant mounts the stairs, and then the camera focuses on the nightly glass of milk he carries up to her. Everyone in the audience is wondering: Is it poison? To heighten the threat and foreboding, Hitchcock placed a lightbulb in the glass so the milk gives off an eerie glow.

To create suspense, your job is to do the literary equivalent of what Hitchcock did by putting that lightbulb in the milk: Build dramatic tension by making the ordinary seem menacing. Two writing tools for achieving this are sensory detail and the slowing down of time.

TURNING UP SENSORY DETAIL

By focusing on the right sensory detail, you can heighten the sense of potential menace in everyday objects.

Read this example from my suspense novel Never Tell a Lie. In it, Ivy Rose, who is hugely pregnant with her first child, realizes someone has been in her house.

Ivy toweled off the dog in the mudroom, locked the door, and hung the spare key back on its hook. She was halfway through the dark kitchen when she stopped. Turned back.

Something was off.

She flipped on the switch, and the overhead fixture flooded the room with light. Her purse was not on the kitchen counter, where she was sure she’d left it. Her keys were gone, too.

Instead, on the counter sat one of her grandmother’s red glass dessert plates. On it lay the newspaper clipping of Ivy and David’s engagement announcement.

A siren went off in Ivy’s head. Someone was in the house. She had to get out of here. But she couldn’t take her eyes off the clipping. Yellow and curled, it looked like the copy she’d found in Melinda’s bedroom at her mother’s house.

But how could it be? Hadn’t Jody gathered up all that material from Ivy’s hospital bed and burned it?

Ivy stepped closer. Where her own face had been cut out, another face now filled the hole. She turned the clipping over and ripped away the photograph that had been taped onto the back.

It took her a moment to process what she was seeing—the face was in a frame from one of the photo-booth strips she’d found in Melinda’s old bedroom.

A low growl sent a chill rippling across Ivy’s back. Phoebe stood in the doorway to the mudroom, teeth bared and snarling, staring past Ivy toward the dining room.

In that short passage, the tenor gradually shifts from normal to fully charged with tension. Taking apart the pieces, here’s what happens and the details that are used to create the suspense:

| What Happens | Details to Increase Tension |

|---|---|

Ivy realizes someone is in the house. | Ivy’s purse isn’t where she left it, and her keys are missing. A newspaper clipping Ivy thought was destroyed is on display on the counter. Ivy’s face in the newspaper clipping has been cut out, and Melinda’s face has been taped into the hole. The dog growls and snarls, alert. |

Ivy reacts in stages:

- She realizes that something is off.

- A siren goes off in her head.

- In internal dialogue, she asks herself, how could it be?

- A chill ripples across her back.

By making your character hyper-aware and ratcheting the dramatic tension in stages, you create a feeling of impending danger. Suspense is sustained by the absence of anything terrible happening and the continued focus on unnerving details.

When you write suspense, remember that your goal is to heighten anticipation. Here are some useful devices for doing so:

- Atmospherics: Building storm clouds, a flash of lightning, or distant thunder suggest something bad is about to happen, even if they are a bit clichéd.

- Shadows that cover objects, or a bright light that reveals something that was hidden: Create the suggestion of hidden menace with closed curtains, a tarp covering something, a folding screen set up in the corner of a room, a closed (or just barely ajar) door, a shadow, and so on. Or flood the setting with light to suddenly reveal something that was previously obscured.

- Internal sensations: Show that your character feels the anticipation, too. She might pull up her coat collar, pat her pocket to be sure she’s got her mace, or feel her scalp prickle.

- Something that’s not quite right: A telephone off the hook, a broken window, a single high-heeled shoe discarded on a front walk, water left running in a kitchen sink—these not-quite-right details create suspense.

TURNING DOWN THE VELOCITY

Slowing down time increases suspense. I deliberately drew out the moment when Ivy realizes her face has been torn from the old engagement announcement and Melinda’s pasted in.

Here are some tools for slowing things down:

- Complex sentences. To create a feeling of apprehension about what might happen next, use longer, more complex sentences rather than a rat-a-tat subject-verb-object structure.

- Internal dialogue. Let the reader hear your character’s thoughts.

- Camera close-up. You want the reader as close as possible, experiencing firsthand the tension the narrator is feeling.

- Quiet and darkness. Stillness, shadows, and dark suggest hidden menace.

- Exposed tipping point. Isolate and expand the moment when things go from being okay to not okay. In this example, the words “Something was off,” which stand alone as a paragraph by themselves, serve that function.

MODULATING SUSPENSE

Building suspense takes time. No matter how much menace your descriptions carry, the reader will lose interest if you pile on sensory detail after sensory detail. Break the tension by inserting a pause in the tension.

There are many ways to insert a pause into suspense. A telephone rings. One of the characters cracks a joke; in real life, we use humor to get through tense times. Or something that seemed menacing is revealed to be ordinary: A scary shape turns out to be the shadow of a moonlit tree; scuffling outside a window is just a squirrel; the person placing a hand on your protagonist’s shoulder at a tense moment turns out to be his best buddy.

Or suspense can continue to rise as something bad happens. Here’s how Never Tell a Lie continues:

Ivy turned. A figure emerged from the shadows. The woman who’d been at their yard sale stood there, staring at Ivy. Was this Melinda? Ruth?

Raw terror clawed its way up Ivy’s throat. “Get out of my house.”

The woman stepped into the bright kitchen. She was not pregnant.

“Keep away from me!”

The woman took a step closer.

“Why are you doing this?”

The woman’s gaze dropped to Ivy’s belly. “Because that’s my baby.”

Ivy backed up fast, banging against the kitchen counter. She grabbed one of the knives from the block and held it out in front of her, the tip wavering, the blade catching the light.

“Stay away!” Ivy screamed.

FORESHADOWING VERSUS TELEGRAPHING

Creating a suspense sequence that ends harmlessly is a good way to foreshadow something more sinister that happens later in your novel. For example, in chapter three, your protagonist goes into a dark, dank basement and emerges, joking about spiders and things that go bump in the night. In chapter twenty-three, she goes down into that same basement, and this time she finds the villain waiting for her. Just be careful you’re foreshadowing and not telegraphing. Giving away too much too soon is guaranteed to ruin the suspense.

The line between foreshadowing and telegraphing is a subtle one. Let’s say your female sleuth meets a man who turns out to be a serial rapist/murderer who preys on young businesswomen whom he picks up in bars at fancy restaurants. What would be foreshadowing, and what would be telegraphing? Consider this list of possibilities. Where would you draw the line?

- The man is charming; his nails are manicured, and he smells of expensive aftershave. She finds herself feeling a bit uneasy around him, but she can’t put her finger on why.

- The man’s eyes linger on her chest when they’re introduced.

- When the man shakes her hand, he places his other hand on the small of her back.

- When she gets ready to leave, he offers to walk her to her car, saying there have been some muggings in the neighborhood.

- She finds his direct, penetrating blue eyes unnerving.

- She notices a scratch on his face; he notices her noticing and says his cat scratched him.

- She’s repelled by the man. He reminds her of the college football player who tried to rape her years earlier.

- The man opens his briefcase; she notices a copy of Hustler magazine tucked inside.

- The man opens his briefcase; she notices a roll of duct tape and handcuffs inside.

- The man’s name is Vlad Raptor.

For me, it’s around number seven when foreshadowing starts to tip over into telegraphing.

When you insert a hint of what’s to come, look at it critically and decide whether it’s something the reader will glide right by but remember later with an Aha! That’s foreshadowing. If, instead, it’s like a blinking neon sign that tells the reader what’s coming, you’ve telegraphed.

ENDING SUSPENSE WITH A PAYOFF

You can write a suspense sequence early in your novel that ends with nothing more than a harmless tabby padding off into the night. But as you near one of your novel’s end-of-act climaxes, the suspense sequence should pay off. In other words, the bad thing should happen.

The payoff can be an unsettling discovery of evidence of a crime: a dead body, bloodstained clothing, a weapons cache, or a dug-up basement floor.

Or the payoff might be the revelation of a secret. Finding love letters or a personal diary might reveal a hidden relationship between two characters. Finding drug paraphernalia in a car might suggest that a suburban housewife has a secret life.

Or the payoff can be a plot twist. The bad guy confesses. The sleuth gets attacked, locked in a basement, or lost in a cave. Someone else is murdered. Or the police show up and arrest the sleuth.

Here’s an excerpt from an end-of-act suspense sequence in Michael Connelly’s 9 Dragons. It’s set in the dark, creepy, empty hull of a ship; Harry Bosch is looking for evidence that his missing daughter was kept there:

There was no trash here. A battery-powered light hung from a wire attached to a hook on the ceiling. There was an upturned shipping crate stacked with unopened cereal boxes, packs of noodles and gallon jugs of water. Bosch looked for any indication that his daughter had been kept in the room, but there was no sign of her.

Bosch heard the hinges on the hatch beneath him screech loudly. He turned just as the hatch banged shut. He saw the seal on the upper right corner turn into locked position and immediately saw that the internal handles had been removed. He was being locked in. He pulled the second gun and aimed both weapons at the hatch, waiting for the next lock to turn.

It was lower right. The moment the bolt started to turn Bosch aimed and fired both guns repeatedly into the door, the bullets piercing metal weakened by years of rust. He heard someone call out as if surprised or hurt. He then heard a banging sound out in the hallway as a body hit the floor.

Bosch moved to the hatch and tried to turn the bolt on the upper right lock with his hand. It was too small for his fingers to find purchase. In desperation, he stepped back a pace and then threw his shoulder into the door, hoping to snap the lock assembly. But it didn’t budge and he knew by the feel of the impact on his shoulder that the door would not give way.

He was locked in.

The payoff comes when his search is interrupted by the hatch banging shut. He springs into action, shooting at the door and then trying to force it open. Connelly brings the action to a standstill with that short sentence that sits so effectively on a line by itself: “He was locked in.”

Now You Try: Analyze Suspense (Worksheet 19.1)

Analyze this passage from Hank Phillippi Ryan’s The Wrong Girl:

Jane couldn’t move. Couldn’t risk it. From her place against the wall—light switch stabbing her in the back through her jacket—her line of sight was a narrow sliver.

She couldn’t see the office door across the carpeted hall. She’d have to listen for the click of the latch. Listen for footsteps.

When whoever it was got close enough to her, she’d have them in view. Briefly. Long enough to know the score. If it was Jake and all was well she’d stay hidden, and he’d never know she was there. Nor would anyone else.

In that case, she’d leave, come back later. Make an appointment. All by the book.

Her eyes hurt from having to look sideways. Her neck was complaining. But she couldn’t risk a move.

Footsteps. A door closing.

They were coming.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

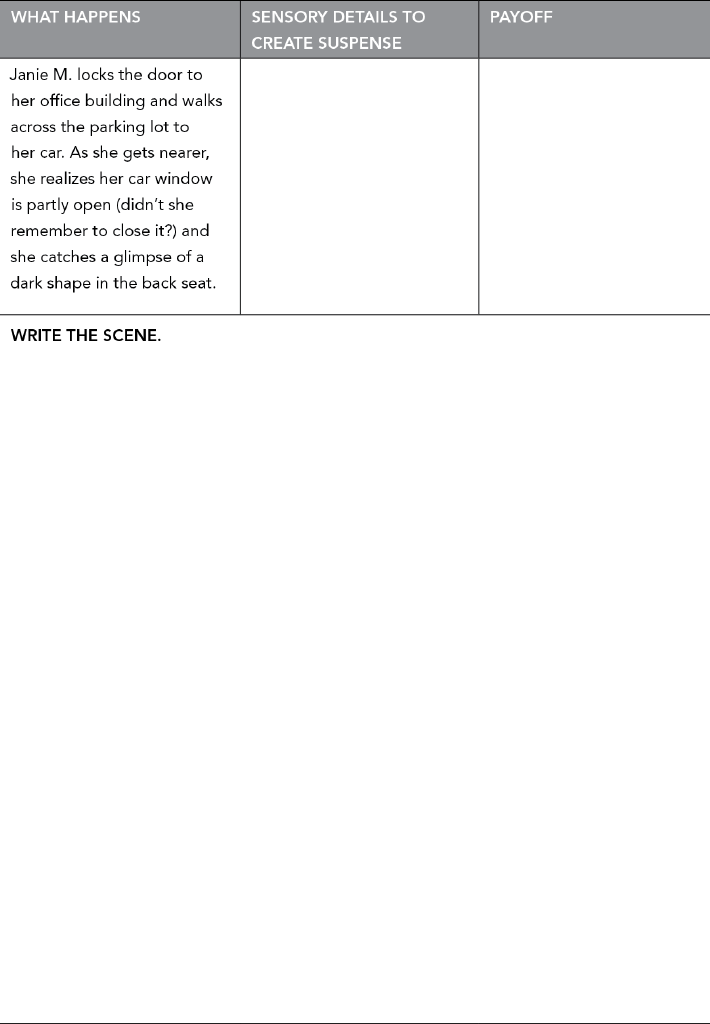

Now You Try: Create Suspense (Worksheet 19.2)

Using the simple scene description below, make a list of sensory details you might use to create suspense. Try to use details that incorporate all the senses. Decide what the payoff will be. Then write the scene.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

On Your Own: Writing Suspense

- Pick a novel you’ve read that is filled with suspense. If you can’t think of one, pick anything by Jeffery Deaver or Mary Higgins Clark. Skim the last third until you find a scene with rising suspense. Examine how the author creates dramatic tension and the sense of anticipation. Does the author provide moments of respite, and how? What’s the payoff?

- Write (or rewrite) a suspense sequence from your outline, focusing on sensory detail and slowing down time to create rising tension.

- Continue writing. Use this suspense checklist to guide your work:

__ Use sensory detail to make everyday objects seem menacing.

__ Consider using the weather, obscured objects, or your character’s internal sensations.

__ Don’t rush. Use description, internal dialogue, and complex sentences to slow the pace.

__ Pull the camera in close.

__ End suspense with a payoff.

__ Foreshadow; don’t telegraph.