Chapter 24

Writing the Coda

“Readers don’t want to guess the ending, but they don’t want to be so baffled that it annoys them.”

—Sue Grafton

Mystery novels usually end with a final scene or two of reflection. I call it the coda. It contains the final resolution or clarification of the plot. Coming after the book’s pull-out-all-the-stops final climax, the coda is like a cleansing breath after vigorous exercise. It’s a chance to tie up loose ends. The coda might be nothing more than dialogue between two characters talking about what happened. It might be an extended internal dialogue in which your main character thinks about the events of the story. It might include a lighthearted scene between your protagonist and the love interest. By the end of the coda, all of your plot’s puzzle pieces should fit snugly together.

THE FINAL CODA: AN EXCERPT

Here’s part of the ending of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep, a novel about pornography and blackmail, and one of the first classics of the hard-boiled genre. As you read, think about how the main character’s introspection puts the story in perspective and provides a sense of closure.

I got into my car and drove off down the hill.

What did it matter where you lay once you were dead? In a dirty sump or in a marble tower on top of a high hill? You were dead, you were sleeping the big sleep, you were not bothered by things like that. Oil and water were the same as wind and air to you. You just slept the big sleep, not caring about the nastiness of how you died or where you fell. Me, I was part of the nastiness now. Far more a part of it than Rusty Regan was. But the old man didn’t have to be. He could lie quiet in his canopied bed, with his bloodless hands folded on the sheet, waiting. His heart was a brief, uncertain murmur. His thoughts were as gray as ashes. And in a little while he too, like Rusty Regan, would be sleeping the big sleep.

On the way downtown I stopped at a bar and had a couple of double Scotches. They didn’t do me any good. All they did was make me think of Silver-Wig, and I never saw her again.

Not much happens here: Detective Philip Marlowe walks out of a house, drives to a bar, and has a couple of drinks. The action itself is irrelevant except to serve as a foil for Marlowe’s final bitter reflections. But these poignant paragraphs provide an elegiac coda as Marlowe leaves the story behind figuratively and literally (I got in my car …). He contemplates “the big sleep” to which others have gone and ruminates about the meaning of death (What did it matter where you lay …) and how he’s become tainted by what’s happened (I was part of the nastiness now …). He stops at a bar and knocks back two double Scotches, presumably to forget, but instead he remembers Silver-Wig, the girl who helped him dodge the big sleep (… and I never saw her again.).

PURPOSE OF THE CODA

The final coda should not be a long scene that belabors every point in the story or gives a cumbersome synopsis. It shouldn’t introduce new plot strands or new characters. Instead, the coda should bring the protagonist full circle and show the reader how he’s been changed by what happened. Here are some of the purposes it can serve:

- Resolve the major conflicts. These include internal conflicts—the dilemmas your main character had to deal with, such as reconciling a past event—as well as external conflicts—the obstacles your protagonist had to overcome to find the killer.

- Account for the facts. This is your last chance to make sure all the important facts are accounted for: why the villain did what he did and who was hiding what secrets.

- Tell what happened next. Clue the reader in on what’s happened since the book’s climactic action sequence. Did the protagonist survive the wounds he suffered in the final shoot-out? Has the villain been arraigned? Were the stolen jewels returned to the museum?

- Resolve the subplots … The coda is a good place to put the finishing touches on any subplots, such as a romance or rivalry between characters.

- … Or leave a subplot dangling. You may want to leave a subplot involving your cast of supporting characters unresolved. For example, the detective might be on the brink of connecting with a love interest, or the sleuth might be relegated to desk duty and fighting charges of insubordination at work. Dangling subplots can be carried forward into the next series novel.

- Get the sleuth’s take on the case. Is she satisfied with the outcome? Does she feel justice was served? Does this change her in any fundamental way—does it show that there is hope in this world, or only despair?

- Sail off into the sunset … The final scene can be a happily-ever-after ending with your characters setting out into a world that’s safer because evil has been defeated.

- … Or leave your hero off balance. The final scene can leave your protagonist feeling unsettled, with issues to be resolved (in the next book!). Maybe the killer was captured, but the person who put him up to it got away. Maybe your hero did something questionable that he’s going to have to live with (killed someone, told lies, put a loved one in mortal danger, slept with the enemy).

- Inject a final shocker. You save a final plot twist for the coda. For example, in one of the final chapters of Gone Girl, Nick has left his wife, Amy, and is about to publish a tell-all novel revealing her as a sociopath, when she informs him that she’s pregnant with his child. He’s stuck. He’ll have to stay with her and keep her secrets hidden in order to protect their child.

- Leave the reader satisfied. The ending need not be a happy one, but it should be satisfying.

FINAL WORDS

The last lines of your book should feel like an ending. One way of doing this is to show your protagonist looking back and looking forward, like the two-faced Janus from Roman mythology, putting the past to rest and moving on. Here are examples of final lines from best-selling mysteries that show the protagonist moving on:

With a deep sigh, George put his car in gear and slowly edged back on to the Scardale road. No matter what the future might hold, it was time to take the first step on the road to burying the past, this time forever. (A Place of Execution by Val McDermid)

Overhead, the sky was a brilliant blue. The hot Miami sun warmed hearts and minds and points south. A late-afternoon breeze rattled in the palms and caused the water of Biscayne Bay to gently lap against the boat hull. Life was good in Florida. And okay, so I was going back to working on cars. Truth is, I was pretty happy with it. I was looking forward to working on Hooker’s equipment. I’d seen his undercarriage and it was damn sweet. (Metro Girl by Janet Evanovich)

She walked away from that building of captive souls. Ahead was her car, and the road home. She did not look back. (Body Double by Tess Gerritsen)

Spend time crafting your final sentences. Make them memorable, and leave readers looking forward to your next book.

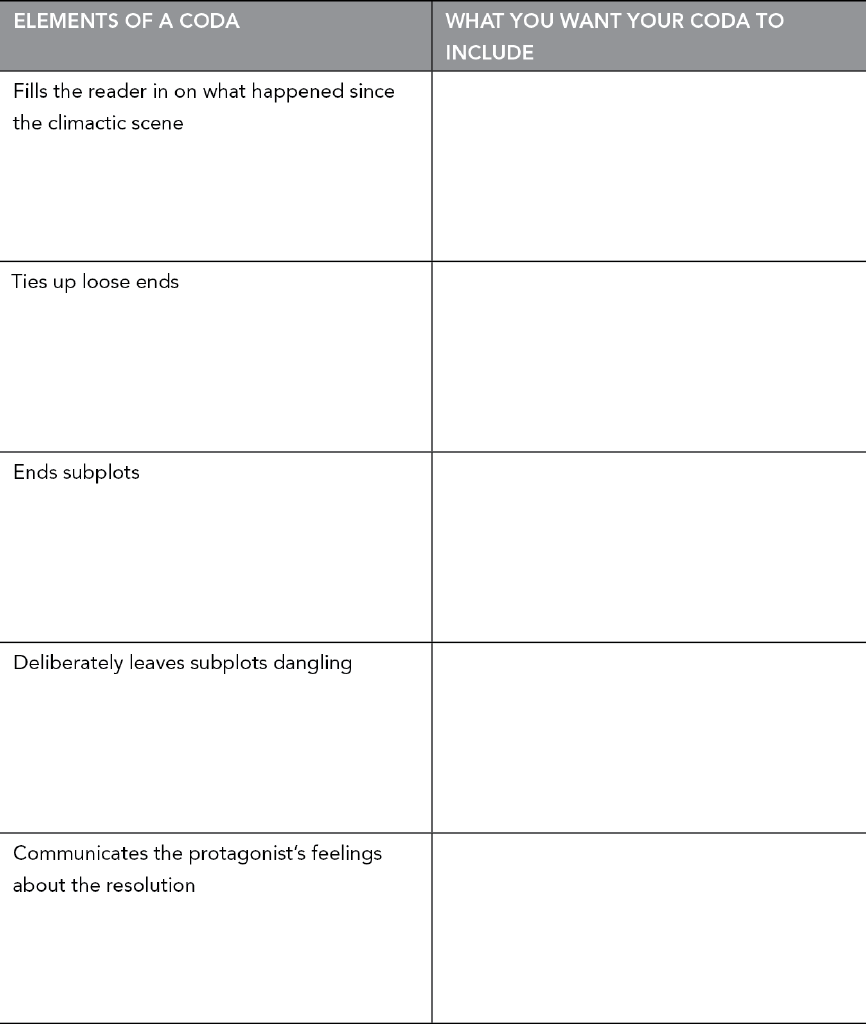

Now You Try: Write the Final Coda (Worksheet 24.1)

A final coda is a workhorse of a scene, so a little housekeeping is needed to make sure it provides a satisfying conclusion to your novel. Make a list of everything you want the ending to accomplish.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

On Your Own: The Final Coda

- Decide the backdrop for the coda: What action will take place while your characters reflect on what happened?

- Write the coda. Use this checklist to guide you:

___ Tell what’s happened since the last climactic scene.

___ Summarize the resolution, and communicate the protagonist’s feelings about how things turned out.

___ Resolve any loose plot and subplots.

__ Tell what happened since the climactic final scene.

___ Make the final lines sing.