Chapter 29

Placing Your Novel with a Traditional Publisher

“Traditional publishing and indie publishing aren’t all that different, and I don’t think people realize that. Some books and authors are bestsellers, but most aren’t. It may be easier to self-publish than it is to traditionally publish, but in all honesty, it’s harder to be a bestseller self-publishing than it is with a house.”

—Amanda Hocking

Traditional publishing houses have been publishing mystery novels since 1876, when Harper and Brothers published The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins. The Big Five (Penguin Random House, Macmillan, HarperCollins, Hachette, and Simon & Schuster) all have imprints that feature crime fiction, and some have digital-only crime fiction imprints. Amazon’s publisher for crime fiction, Thomas & Mercer, functions much like a traditional publisher. Smaller traditional publishers that specialize in crime fiction include Soho, Permanent Press, Midnight Ink, and Seventh Street Books.

NAVIGATING THE PATH TO TRADITIONAL PUBLICATION

The path to traditional publishing begins with a finished, polished manuscript. Really. No, you cannot sell a partial manuscript or a proposal for a first mystery novel to a traditional publisher—not unless you’re James Patterson or Beyoncé.

The usual path to traditional publishing starts with a query. The author crafts a query letter pitching the novel and sends it (or his literary agent sends it) to an editor at a publishing house. If the editor likes the pitch, he’ll request the manuscript. If he likes the manuscript well enough, most editors have to pitch it to their publishing boards before making an offer.

If the author accepts the offer, the author or his agent negotiate the contract that defines such essentials as the following:

- royalty or flat fee

- advance and payment schedule

- delivery date

- publication date

- second-use rights (e-book, audio, translation, etc.)

- free author copies of the book

- review of the cover design

- … and much more

Don’t ignore the “and much more.” Contracts are long and complicated affairs. Publishers draft boilerplate contracts with terms that benefit them. If you do not have a literary agent negotiating on your behalf, I strongly suggest that you bone up on publishing contracts. The Authors Guild website has a legal services section with postings open to nonmembers. There are also books on the topic. If you can afford it, hire an attorney who is knowledgeable about intellectual property and book publishing (not the one who helped you settle an estate or fight a lawsuit).

UNDERSTANDING WHAT TRADITIONAL PUBLISHERS DO

Traditional publishers edit, format, design, produce (in both physical and digital versions), market, distribute, and sell the book. Traditional publishing is notoriously slow. Months can pass from when a manuscript is submitted and accepted or rejected. Then the book’s editing and production cycle can take another nine months to two years before the final book is available from retailers. In general, traditionally published books command higher prices than self-published books, but authors get a smaller percentage of the proceeds.

Traditional publishing offers authors and their books better visibility in the marketplace, including reviews in the mainstream media and book industry trade journals like Kirkus Reviews and Publishers Weekly. Traditionally published books also are more likely to find a spot on the shelf at brick-and-mortar bookstores, making it easier for readers to discover them.

GETTING A LITERARY AGENT

You need a literary agent if you want your book to be considered by most large and medium-sized traditional publishing houses. Their mystery imprints each publish a few debut mystery authors every year, and most of them are picked from manuscripts submitted by literary agents. You may not need a literary agent to be considered by a small press. Most small presses post submission guidelines on their websites.

What a Literary Agent Does for You

Literary agents have become the gatekeepers for traditional publishing. Many agents critique their authors’ manuscripts, vetting revisions until they deem a manuscript strong enough to pass muster. A literary agent submits your manuscript to editors she believes, from past experience and track record, are looking for the kind of mystery novel you’ve written. Then the agent follows up with those editors to make sure your manuscript doesn’t get lost in the heaps of submissions. The better your agent’s reputation, the more quickly your manuscript is likely to rise to the top of an editor’s slush pile and get considered.

However, having a brilliant agent doesn’t guarantee a book contract. When your book gets rejected—and most submissions do at least a few times—your agent should tell you the reasons given and send you the rejection letters. Your agent will contact you when an editor expresses interest. She will try to encourage an auction—a bidding war between publishing houses for your novel—and negotiate contract details with your interests at heart. Many agencies have access to an attorney who reviews contracts as needed. Agencies also negotiate foreign language rights and subsidiary rights like audiobooks or a movie option.

All reputable literary agents work strictly on commission. That’s the built-in incentive. If your agent doesn’t sell your book, he doesn’t get paid. Checks from your publisher go to your agent, so you don’t get paid until your agent does. Agents take out their agreed-upon commission (typically 15 to 20 percent) from book advances and royalties, and pay authors the remainder.

What a Reputable Literary Agent Should Not Do

An agent who charges you for services prior to selling your novel is violating accepted industry practices. Some agents charge for expenses such as photocopying. This is fine if it’s been documented and agreed upon up front. But beyond that, if you’re being charged for services before you get a book contract—whether they call it a reading fee, a marketing fee, a retainer, or another euphemism—something’s fishy.

When in doubt, refer to the Canon of Ethics on the Association of Authors’ Representatives (AAR) website.

How to Target Agents Who Are Right for You

Honesty, integrity, chutzpa, smarts, and knowledge of the book business and contract negotiations—those are the basic ingredients of a competent literary agent. There are hundreds of them out there, many of them former editors and publicists with inside knowledge of the publishing business. Some agents have formidable track records. Others are just starting out and hungry to prove themselves.

Finding the right agent for you is a little bit like finding a soul mate, though the match should be between your writing and the agent’s taste. You want an agent who has unvarnished enthusiasm for your work combined with the knowledge of which editors will share that enthusiasm—that’s the ticket.

Target agents who represent crime fiction. When I last checked the online database of the Association of Authors’ Representatives (AAR), 386 literary agents were listed, and 138 of them represented the mystery genre. To find out which agents are bringing home the bacon, read Publishers Weekly or get a free subscription to the online newsletter Publishers Lunch and read their weekly Deal Lunch, which reports on recent agent/publisher deals. You can find out more information about specific agents in Writer’s Digest Books’s annual Guide to Literary Agents, which prints profiles submitted by literary agents.

Agents receive an overwhelming number of queries each day from authors, so look for ways to make your query stand out. Here are some tips to help ensure your query is seriously considered:

- Obtain referrals from friends, relatives, and fellow writers. A referral from a friend, colleague, or family member, ideally a published author, editor, or reviewer, is hands down the best way to get your work considered. Ask everyone you know—you’ll be surprised to discover that you know people who know literary agents. Network with published writers you meet at mystery conferences, or join the local chapter of Mystery Writers of America, Sisters in Crime, or the National Writers Union. I have found that most published mystery authors are happy to share their experiences with agents, and you might even get a referral.

- Meet agents at writing conferences and workshops. Agents teach, speak on panels, critique manuscripts, and listen to pitches from writers at many writing conferences and workshops. They are looking for new talent. At mystery conferences like the New England Crime Bake, Sleuthfest, Thrillerfest, and Left Coast Crime you can sign up to pitch your novel to an agent.

- Identify agents who represent books like yours. A little online research (for instance, Google “James Patterson’s agent”) will quickly turn up the name of the literary agent who represents any well-known author. Or go to the mystery section of a bookstore and pull out every recently published mystery novel that reminds you of your own, or that is written by any author whom you admire. Read the acknowledgments page. Most writers thank their agents. Make a list of which agent represents which author. It’s a good bet that any of those agents are worth querying.

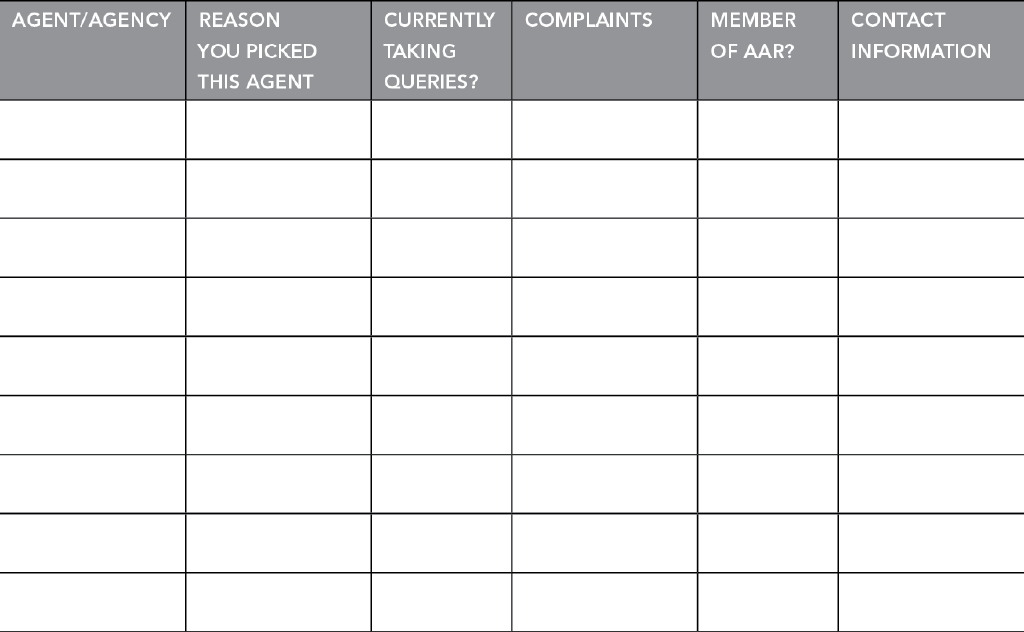

Now You Try: Create an Action Plan to Target Agents (Worksheet 28.1)

1. In the first column, compile a list of ten to thirty potential agents.

2. Write down why you picked each agent:

- name of the friend, relative, colleague, or other writer who referred you

- date and event where you met the agent

- published mystery author this agent represents

- the great deal this agent recently negotiated

3. Cut one: Check with the agency’s website and eliminate any that are currently not taking queries.

4. Cut two: Notice whether any agency on your list has had complaints against it, and if so, do you see a pattern? Websites with useful information for identifying agents with sketchy reputations include Preditors & Editors and Writer Beware (hosted by Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America).

5. Check to see if the agent is a member of the Association of Authors’ Representatives (www.aar-online.org/). While there are good agents who are not AAR members, it may be something to consider when you prioritize.

6. Sort: Prioritize your list, from most desirable to least.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

WRITING THE QUERY

Wouldn’t it be nice if you could attach your manuscript to an e-mail, shoot it over to a list of agents and editors, and instantly get a yes? Unfortunately, the publishing world doesn’t work that way. Most agents and editors like to be queried first—which is a fancy way of saying they want to hear the elevator pitch of your novel so they can decide if it’s worth their while to read it.

Check the agent’s website to see if she has specific requirements for queries. An agent will usually say, for instance, whether she wants to be queried by snail mail or e-mail, and whether she wants a pitch only or pages, too. A typical query includes:

- a letter, customized for each agent

- a synopsis or the first ten pages of the manuscript

Never send your entire manuscript unless an editor or agent has specifically asked for it. An agent is more likely to respond to your query if you demonstrate some knowledge of who she is, so never send a boilerplate query letter that begins Dear Agent.

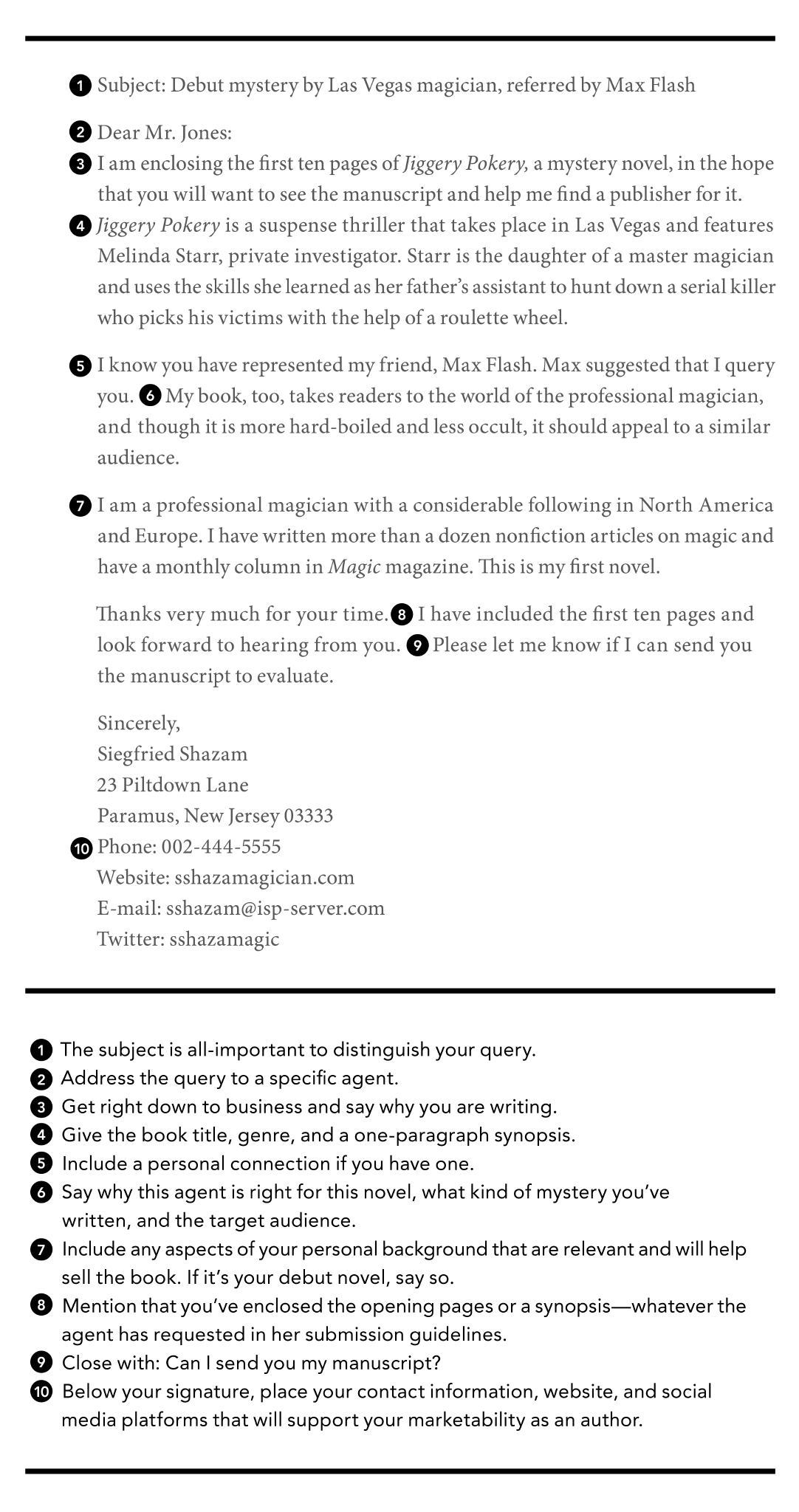

Anatomy of a Query Letter

The query letter should be short, no more than one printed page. Agents tell me they prefer direct, business-like letters that convey the concepts of your novel so enticingly that they simply must see your complete manuscript posthaste. The query is 100 percent marketing, somewhat like the copy on a book jacket, and its only purpose is to make an agent or editor want to read your book.

Keep in mind that the lion’s share of queries is screened by publishing interns or junior staffers. Your subject line is paramount.

Here’s some extra ammunition to use if you’ve got it. Let the agent know if:

- an author, editor, or other mutual acquaintance suggested you send your manuscript to this person

- you have anything in common with this person (attended the same college, grew up in the same town in Minnesota, both used to work in advertising)

- you met this person at a conference, bookstore, party … wherever

- you heard this person speak somewhere, or you read something this person wrote; comment on some idea you took away from his remarks

- established, respected writers or media personalities have read and liked your manuscript and agreed that you can convey their enthusiasm

- this will be your first published novel; publishers and agents are looking for undiscovered talent

- you’ve been published before (self- or traditionally) and sold an impressive number of books; say how many and over what time period

- you or your book are in some way comparable to a best-selling author or novel; cite the comparison, but avoid hyperbole

Finally, make sure your query is flawless—no spelling, grammar, or punctuation errors, no clunky sentences or awkward transitions. Triple-check that you have spelled the agent’s name correctly.

WRITING THE SYNOPSIS

The synopsis for querying agents and editors is much shorter and less detailed than the before-the-fact synopsis you may have written while planning your novel. Some writers, me included, find this short synopsis harder to write than the novel. You have only a page or two to get it right, and the future of your beloved novel hangs in the balance. The synopsis has to be informative, but it cannot be boring. It has to make your novel sound fabulous, but it can’t be puffed up with self-praise.

Say it with me: The synopsis is a marketing pitch. Remember, this is not a blueprint of the book or a summary of everything in it. It should be as specific as possible, including details that make your book unique.

To get a feel for how to write a synopsis that pitches your mystery novel, visit an online bookstore and read publishers’ descriptions of mystery novels. Here are three excerpts from publishers’ descriptions of mystery novels:

Convicted murderer Melvin Mars is counting down the last hours before his execution—for the violent killing of his parents twenty years earlier—when he’s granted an unexpected reprieve. Another man has confessed to the crime. Amos Decker, newly hired on an FBI special task force, takes an interest in Mars’s case after discovering the striking similarities to his own life. (The Last Mile by David Baldacci, Grand Central Publishing)

Chief Inspector Armand Gamache of the Surêté du Québec and his team of investigators are called in to the scene of a suspicious death in a rural village south of Montreal. Jane Neal, a local fixture in the tiny hamlet of Three Pines, just north of the U.S. border, has been found dead in the woods. The locals are certain it’s a tragic hunting accident and nothing more, but Gamache smells something foul in these remote woods, and is soon certain that Jane Neal died at the hands of someone much more sinister than a careless bowhunter. Still Life introduces series hero Inspector Gamache, who commands his forces with integrity and quiet courage. (Still Life by Louise Penny, Minotaur Books)

On a hillside near the cozy Irish village of Glennkill, the members of the flock gather around their shepherd, George, whose body lies pinned to the ground with a spade. George has cared for the sheep, reading them a plethora of books every night. The daily exposure to literature has made them far savvier about the workings of the human mind than your average sheep. Led by Miss Maple, the smartest sheep in Glennkill (and possibly the world), they set out to find George’s killer. (Three Bags Full by Leonie Swann, Doubleday)

Your synopsis can be up to two pages long, single-spaced. Like publisher synopses, yours should introduce the main characters, establish the setting, and summarize your story including your opening gambit and some of the plot twists. You don’t have to reveal the ending.

Here’s the first page of the synopsis for my novel Come and Find Me.

For two years, Diana has been a recluse. The thirty-five-year-old computer security expert rarely leaves her modest suburban ranch house in a Boston suburb, not since she returned from Switzerland. There, in the shadow of the Eiger, she and her partner in life and in work, Daniel Spector, had been climbing the icy face of Waterfall Pitch. She was securing her own footing in the frozen cascade of water when Daniel slipped. Diana is haunted by the sound of his cry echoing across the gorge and by the image of his body frozen and wedged somewhere in an icy crevasse, suspended there forever because of that one moment when she looked away.

She and Daniel had been part of a group of hackers. Most of them were idealists whose goals were to expose security flaws and shake software companies, businesses, and government agencies out of their complacency. For some, the goal was to prove how smart and superior they were. But one after the other, fellow hackers peeled away. Some went to the dark side to make their fortunes by creating serious mayhem. Others went legit, taking high-level security jobs. Diana and Daniel, along with Daniel’s best friend, Jake, were about to open a security consulting company and get paid to ferret out security flaws and protect systems from predatory hackers. The trip had been to celebrate their impending transition.

Diana returned home devastated. She broke all the mirrors in her house, unable to bear the sight of her own reflection. For months she remained housebound, turning her home into a fortress ringed with invisible electronic security fences. Redundant satellite, fiber optic, cable, and DSL feeds ensured that the Internet, her link to the outside, never goes down. Whatever she needed from the outside she had delivered, and her only visitors were her sister, Ashley, and Jake.

When Diana’s sister goes missing, Diana is forced out of her protective crouch. She …

A synopsis offers a fast-forward overview of your book. Here are some techniques to borrow from these examples in writing your synopsis:

- Write in the present tense.

- Summarize your main characters.

- Describe the setting and context.

- For once, it’s okay to tell and not show; dramatizing takes too long.

- Summarize the plot, hitting the major plot twists.

- Communicate your protagonist’s motivation and key challenges.

- Don’t try to explain every character and plot point.

SENDING OUT QUERIES

Sending out queries and waiting for responses can be nerve-wracking, and it only gets worse after rejections start coming in. Try to disconnect from the whole process emotionally. Think of it as a marketing campaign for which you’re the hired help—because as surely as there are death and taxes, you will get rejections. This race goes to the persistent.

Make a plan, and keep track. Send e-mail queries to four or five of your top choices. Each time you get a rejection, send out a query to the next agent on your list. If it’s been four weeks and you haven’t gotten a response, send a follow-up e-mail. If after eight weeks you still haven’t heard, forget about that agent and send out the next query.

QUERYING A SMALL PRESS

Just like a major publishing house, a small press enters into a contract with the author, edits and publishes the book, markets and handles distribution, and pays the author royalties. Generally speaking, a small press offers a smaller advance and has smaller print runs than larger publishing houses.

Most small presses post their submission guidelines on their websites. Some small presses accept unagented queries.

Targeting small presses requires due diligence. There are plenty of scam artists who dangle the promise of a book contract while their only goal is to take your money. So research the reputation of any small press before you query:

- Make sure it has a track record for selling books like yours.

- Look at some of its finished books. Do they look professionally designed and presented? Is the text clean and copyedited?

- Google the name of the press with the words “publishing scam.”

- Check out the publisher on the Preditors & Editors website or in Writer Beware on the Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America website.

- Look at the track record of some of the house’s published books. (Use Amazon’s “Sales Rank” feature.)

A red flag should pop up if you submit your manuscript and the editor starts talking about reading fees, publishing fees, a fee for cover art, or a fee to list your book on Amazon. You should also be suspicious if the editor suggests an unusually high list price for the book.

Ask about their distribution channels. It will be easier to get your book into bookstores and libraries if the small press sells its books through a major distributor such as Ingram Content Group or Baker & Taylor, Inc.

If you sell your manuscript to a small press without the help of a literary agent, I strongly recommend you either hire an attorney who knows how to evaluate a publishing contract or do the research required to evaluate and negotiate it yourself. You want to be sure your best interests are represented across the range of important issues, including how royalties are computed and reversion of rights (a.k.a. what happens when your book goes out of print or the small press goes belly-up).

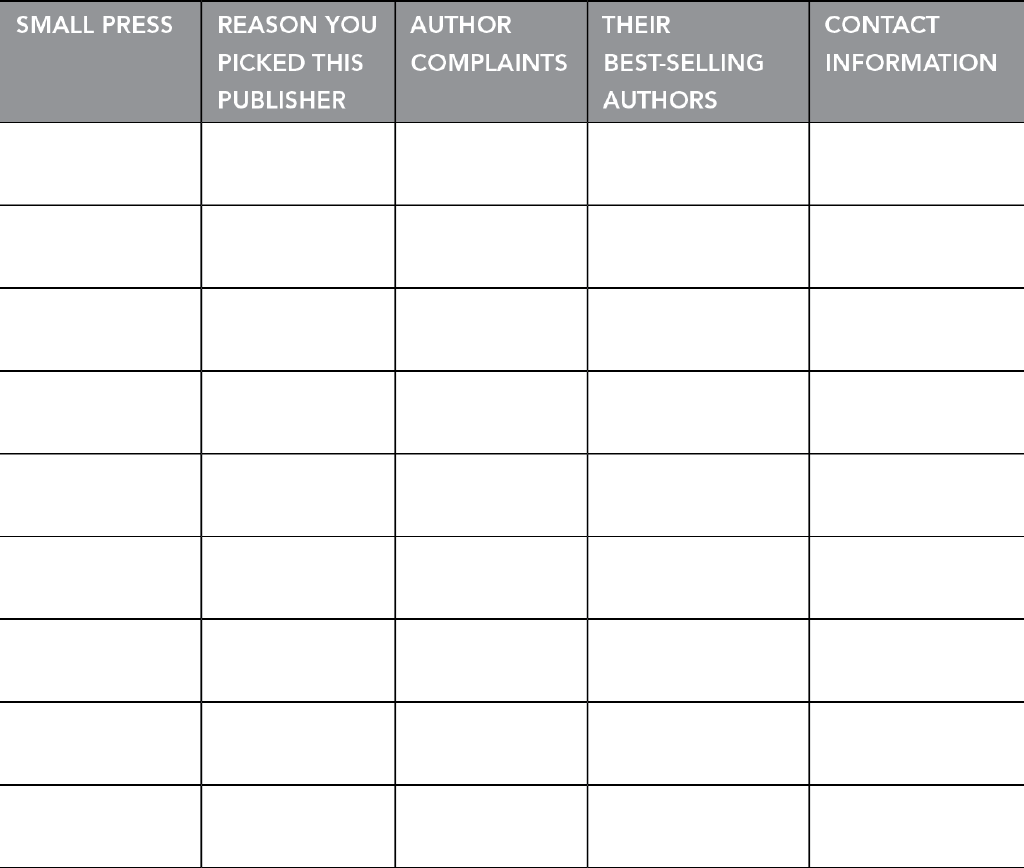

Now You Try: Prepare to Approach Small Presses (Worksheet 28.2)

1. Decide if you want to be published by a small press.

2. Compile a list of small presses to target—fill in the first column below:

3. Check the reputation of each publisher on your list by consulting the Preditors & Editors website (pred-ed.com). Try to distinguish between a few disgruntled authors and a pattern of poor business practices. Eliminate any publishers with consistently reported problems.

4. Check out each publisher on your list in Novel & Short Story Writer’s Market, published by Writer’s Digest Books. Based on what you glean, add this publisher’s contact information or eliminate it from the list.

5. Search Amazon for mysteries published by each publisher, and note their sales rank. Search inside some of its books to see if they are professionally presented and edited. Decide whether this publisher seems like the company you want to keep.

6. Sort. Prioritize your list from the most desirable small presses and independent publishers to the least.

7. For your final choices, visit the publisher’s website and prepare a query package that meets their specifications for submissions.

HANDLING REJECTION

Expect rejection. You’ll have agents who say, “No thank you,” to your query letter; you’ll have editors who ask to see a chapter (shout for joy!) and then ask for the manuscript (cross all fingers and toes), and then send a letter saying sorry. An editor may even hold on to your book for months as your hopes mount, only to reject it.

Remind yourself how competitive this business is. A good agent already has a full plate of clients vying for attention. Each editor has slots for only a few new authors in a given year.

Most often, the rejection says something boilerplate and generic, like these examples from my very own pile of rejections:

“I am sorry to say that I don’t have the requisite enthusiasm to take on the project and represent it properly.”

“The market is very tight right now, and I am being highly selective about the new properties which I am taking on.”

“I’m afraid I don’t think I’d be able to sell it. The writing is good, but the storyline didn’t work for me.”

But you may get a rejection that goes on at some length about your novel’s strengths and weaknesses. Cherish these, because agents and editors rarely take time to say anything unless they see potential. If you start to see a pattern—for example, if several rejection letters say your main character isn’t strong enough, or if one points to a weakness in your plot and you agree, stop! Consider revising the manuscript to address the problems before sending it out to more agents and editors, and exhausting all of your top choices. Once you’ve been rejected by an agent or editor, you don’t get a do-over.

Even if an editor loves your manuscript, few editors can make yes-or-no decisions unilaterally. The editor usually has to convince other editors, as well as sales and marketing departments, that your book is terrific and that there’s a strong market for it. Book publishing is a business. A decision to publish a book is not a reward for literary quality; it’s a gamble for financial gain.

With each rejection, feel your skin thickening as your ego grows calluses—you’ll need them. Pick yourself up, dust yourself off, and send out a new query. The next one could be the one that clicks.

A FINAL WORD

If your mystery novel is a good one and luck is with you, it will find a publisher. When that happens, break out the champagne. Celebrate!

Then start writing the next book before you get sucked into the vortex of promoting the one you just sold.

On Your Own: Put Together a Query

1. Research the agents and publishers you intend to query; prioritize them.

2. Write a tailored query for each of the first five agents or publishers on your list. Use this checklist to guide you:

___ Address this specific agent or editor by name.

___ In the subject line, lead with what distinguishes this query from the pack.

___ Say why you are writing.

___ Include your book title, genre, and a one-paragraph synopsis.

___ Specify the kind of mystery and the target audience.

___ Say why you think this particular literary agent is right for your novel.

___ Include aspects of your personal background that are relevant and will help sell the book.

___ Include the opening pages or a synopsis—whatever the agent has requested in her submission guidelines.

___ Share any personal connection you have to the agent, including a reminder of where you met this agent or editor, or who referred you.

___ Mention praise for your work from a published writer who has agreed to let you use the quote.

___ Tell the agent or publisher if this is your debut novel.

___ Close with Can I send you my manuscript?

___ Below the signature, place your contact information, website, and social media platforms that will support your marketability as an author.

___ Check for spelling, grammar, and punctuation errors; revise clunky sentences and awkward transitions.

3. Prepare a second batch of five queries that are ready to go out when you receive a rejection.