6.0

HOLY PERSONA

PERSONIFY YOUR CUSTOMERS AND WALK IN THEIR SHOES

In order to animate your understanding of your customers, to give them lives and specific desires, hopes, and dreams, you must craft nuanced, detailed portraits of them. One of the fundamental techniques of HCD is the development of these portraits, referred to as personas. They allow you to take the customer data you have and the observational research you’ve done and create a revelatory story about both the experience you’re offering them now and the new, richer experience you can design. This is where experience architects begin to sketch their building plans and it starts with people first.

You want to create personas both for the people who buy from you today as well as for those who don’t, whom you’re targeting. The research that goes into the accurate portrayal of current and potential aspirational customers and their behavior and goals should be a combination of demographic, psychographic, and ethnographic studies. It must not be guesswork! While not everyone has the time, resources, or budget to pursue each of these types of research in depth, you must make the best effort possible. Even a set of fairly simple interviews with customers can provide a wealth of information to work with.

The big mistake that’s often made in persona development is that they’re based just on supposition about customers. The whole purpose of them is to remind your team that they are in fact selling to real people, so they must be highly specific and drawn from true customer information. Otherwise you run the risk of simply reinforcing false assumptions you’re making about your customers.

Once you’ve collected the data and analyzed it, you want to create a set of composite characters with the details you have about preferences, lifestyle, purchasing habits, and so on. Each of these composite individuals represents a customer group.

One good approach for crafting personas is to describe the range of types of customer in the way characters are introduced in a screenplay or script. Here is a simple example of the original character descriptions for the cast of the Friends television show.1 Typically this is enhanced with visuals, activities, and goals.

This exercise forces you to humanize your customers and those who aren’t coming to you yet, making them much more relatable. This is a remarkably powerful device for developing empathy for them. Remember, every persona has their own influence ecosystem. When it comes to experiences, we need to understand their little worlds to become part of theirs and them part of ours.

As I was researching interesting persona work, I discovered a series of case studies by research and design firm Bolt | Peters, an agency focused on UI, usability, and UX, that I was extremely impressed by. It’s worth noting that like Adaptive Path, Bolt | Peters was acquired by Facebook to bring its unique expertise in-house to design for the future now.

One project in particular, with Dolby Laboratories, stood out for me. Dolby creates surround-sound, imaging, and voice technologies for cinemas, home theaters, PCs, mobile devices, and games. The company wanted to understand the behavior of their customers better by humanizing them. It asked Bolt | Peters to create a set of personas that would serve as a foundation for future projects.2 Rather than crafting the personas on the basis of user circumstance and demographics, Bolt | Peters user focused on studying user behavior. The firm conducted 20 interviews, also investing heavily in quantitative and qualitative customer data analysis. This allowed the team to identify six personas, each with distinct preferences in consumer electronics.

The personas offered realistic pictures of what the consumers with each of these preference profiles might be looking for in their entertainment systems. One of the examples—shown here—introduces us to two Dolby customers: Tim the escapist and Megan the entertainer.

The Original Character Descriptions for the Cast of Friends

Tim is described as a skillful, solitary, and immersive person for whom perfecting audio settings is a stress reliever. He’s an immersive gamer, and enjoys HD movies with full surround-sound. He’s a bit of an audiophile, preferring a perfectly tuned setting and a clean sound. In fact, Tim enjoys his sound so much that even when he’s on the go or working, he uses high-end headphones to enjoy the experience. He’s a tech expert and an evaluative shopper. For Tim, the Dolby brand represents good sound quality, but it should represent perfectly calibrated sound for complete escape.

Megan, on the other hand, is outgoing and community oriented and the consummate entertainer. She wants to be in the middle of the action with her friends and neighbors, and she hosts parties to watch the big game on her flat screen with surround-sound. Megan also uses the surround system for background sound or music. Sometimes she plays games on it, but only when her friends are visiting. Away from home, she occasionally listens to music on the go.

Megan has to have the latest equipment, and she evaluates her purchases with great care. She is an extremist when it comes to quality. For Megan, Dolby represents “theater stuff,” but it should symbolize a way to provide the next best thing to being right there in the midst of the action.

With these descriptions of your customers in hand, your team should now develop scenarios of their interactions with your company and product for all touch-points. In crafting these, you want to describe their needs, goals, aspirations, and intended outcomes. These user scenarios will be instrumental in helping you to create a nuanced and insightful customer journey or experience map. Here is an example of a user persona + scenario shared online by Questionable Methods.3

Scenario

Bob is older and also a father.

He is a self-proclaimed expert.

Bob needs to buy a car for his son.

Bob is computer savvy and knows how much he wants to spend.

Bob gets minimum requirements from his son.

Bob does his research specifically online, in print, and also via Consumer Reports.

After research, Bob uses his home computer to do all of this research.

At this point, the scenario plays out in a series of steps that helps Bob buy a Honda Fit. But imagine you’re working with a car brand that is interested in Bob and other people who also might be interested in a Fit. Understanding the series of different personas who undergo these types of scenarios helps you identify how to reach them—more so, how to better design, market, sell, and serve them.

TECED, a UX consultancy founded in 1967 in Ann Arbor, Michigan, provides user-modeling services. They offer a helpful description of their process:

Persona development begins with assumptions about user profiles, based on data from initial market research. Through interviews and observation, researchers expand and validate the profiles by identifying goals, motivations, contextual influences, and typical user stories for each profile. Having a fictional person (persona) representing a profile grounds the design effort in “real users.”

In general, personas and scenarios should cover the following attributes and behaviors:

Name

Age

Lifestyle and work style

A one-liner with supporting narrative that distinguishes the persona from others:

For example, Brian is a 40-something who when online behaves like a 20-something (swiping with vigilance until he finds what he needs) and aspires to engage in experiences that contribute to his vision of becoming a creative force in his world—he’s a revolutionary!

Key attributes and characteristics that will affect user experience:

Expectations of the product

Channels and channel integration (i.e., app, website, social, mobile)

Frequently performed tasks + desired tasks

Tools and touch-points used

Trusted advisors and resources

Pain-points relevant to the design space (and experience architecture)

Goals and aspirations that the product can solve or unlock

Scenarios to get to, through, and post-product usage

In developing personas this is a very helpful set of questions to ask about your customers:

Who are we designing for?

What activity (or activities) are they attempting to complete?

What are the contexts in which they are trying to operate?

What is familiar to them?

What are their needs and desires?

How do they think about this space?

What are their goals?

What motivates them?

What are some of the things our user/customer/audience might do?

What cultural considerations should we be aware of?

What are the analogous competitive experiences?

What technologies or devices are involved?

What is the technology environment intended to support this project?

What are the business goals? (Funding? Support? Vision?)

The contexts in which customers are engaging with your company or product are vital to keep in mind. Stephen P. Anderson, a speaker and consultant based out of Dallas, Texas, whose work focuses on design and psychology,4 describes the design of experiences as involving “People, their Activities, and the Context of those activities.”

Sample Context to Consider (courtesy of Stephen P. Anderson, poetpainter.com)

Anderson developed a rich visual that helps to keep this in mind.5

Running through the middle of the peanut-shaped diagram is a horizontal line that divides explicit considerations (tasks, users, business goals) from deeper considerations—the insights, motivations, behaviors, and other, softer focus areas that separate the good experiences from the great.

As you are making these considerations, you want to include descriptions of people’s desires, belief systems, prior experiences, emotions, and personality type. You also want to describe the types of activities they like to do, and not only with your products. These activities should include ones that aren’t necessities, but that they value highly, such as types of entertainment they enjoy.

The types of context you consider should include where they live, the type of community they live in, and cultural issues, as well as what they might have been experiencing on a given day when they engage with you. Don’t be afraid to test this model out with you as the subject.

ASSESS PROBLEMS AND OPPORTUNITIES

The next step here is to evaluate opportunities for solving problems or introducing new solutions. You should take the personas and scenarios and encapsulate what you’ve learned about your customers and their expectations, challenges, and behaviors into a brainstorming workshop or series of concept sessions, along with your customer journey or experience map. In these sessions, you will consider the experiences of your profiled customers at every stage of the journey—before, during, and after transactions—assessing also what they share with others in each step and in all ways, for example, in the variety of social networks, review sites, and also in your customer surveys and other research done with them.

To get momentum quickly and keep the team on board, start small. Don’t try to come up with a plan for your whole ecosystem all at once. One possible approach is to start with a series of gap analyses, comparing the current experience you’re offering to what it could be in terms of brand promise versus reality, product promise, customer support/service, community building, and loyalty/advocacy. This is the experience divide for which you can immediately solve.

At a minimum you want to make these five assessments for this basic set of engagements:

1. Awareness

2. Consideration

3. Action

4. Ownership

5. Loyalty/advocacy

Let’s take the case of brand promise as an example. Shown opposite is a quadrant where brand promise is evaluated against various personas.

A great technique for making these evaluations is to play out a series of if this, then that (IFTT) scenarios. Ask yourself: If someone wants to learn more information about a product or service, what can they do? You might say they can click or swipe their way toward a landing page or microsite. Yes, for those familiar with geek culture, in programing IFTT is a service for stringing together that connects different web applications such as Facebook, Evernote, Weather, Foursquare, and Dropbox, developed by Linden Tibbets.6 It’s used because it helps to keep in mind all possibilities. It works the same way in experience evaluation.

Going through this process allows you to formulate a good understanding of experience you should be offering for each customer type at each moment of truth. For example, if your customer visits YouTube seeking a video overview of your product or company, then you should be sure to have assembled (curated and created) a vast quantity of useful videos for a variety of contexts, ambitions, and keywords.

Evaluating Brand Awareness against Different Personas

If a user has a problem with your product and needs help, then you should have outlined several paths for her to contact you in ways that meet her expectations and make her feel better about the product even after the negative experience.

If a customer is seeking a relationship beyond purchase that helps him continually add value to the product experience, then you should have introduced programs that teach users new ways to use and enhance the product and new services that extend the life of the product as a means of building the relationship. Additionally, you should enhance communication with the customer throughout the product lifecycle.

Think of these IFTT scenarios as storylines. They will identify for you the new experiences you must begin designing. This manner of IFTT assessment leads to planning that is more activity-centered and attends to the full range of customer needs and desires.

Once you’ve completed these steps, you will have experienced the current customer experience for your variety of personas and surfaced a number of gaps between what you’re offering and what you should be offering. Now you must begin to formulate your plans for the new, improved experiences you’ll design.

1 http://popculturebrain.com/post/29583091480/the-original-character-descriptions-of-friends.

2 boltpeters.com/clients/dolby/.

3 www.questionablemethods.com/2011/11/scenarios-are-your-product-ideas.html.

5 www.poetpainter.com/thoughts/files/Fundamentals-of-Experience-Design-stephenpa.pdf.

6 www.quora.com/Who-is-the-team-behind-ifttt-com.

6.1

STORYTELLING

LET ME TELL YOU A STORY

STORIES ARE THE CREATIVE CONVERSION OF LIFE ITSELF INTO A MORE POWERFUL, CLEARER, MORE MEANINGFUL EXPERIENCE. THEY ARE THE CURRENCY OF HUMAN CONTACT.

—ROBERT MCKEE

A good customer experience ecosystem grabs customers’ attention and then delights them all through their journey with you. It should engage and move them in the same way a good book pulls you into its pages, the way you become the star of a movie, or the way you become the hero in a video game. Each of these examples is a type of story; so is customer experience. This means that your team must play the role of storyteller.

Storytelling is an ancient art thought to have been practiced around the fire by our prehistoric ancestors. We have an innate desire to be told stories, and we form strong attachments to great storytellers.

Sadly, most of the time, other than in the best advertising, companies don’t act as storytellers. Rather than immersing people in an engaging story, we talk at people, hawking our brand message. In doing so, we most often sensationalize and overdramatize, making our stories implausible and often even annoying.

A great storyteller is highly attuned to the reactions the story is eliciting, listening carefully for how the story is being received and modulating the story accordingly. The pacing of the story is carefully crafted to hold attention. Vivid images are conjured and the emotions are stirred. Scenes or chapters open in compelling ways, and the ending of each draws us powerfully on to the next. The end of the book, game, movie, or composition leaves us wanting more. The story has put us through an experience that we want to revisit again and again, as any parent who has ever read a classic children’s story to a son or daughter knows all too well. It is just this kind of experience that you should be designing for customers.

The value of companies learning to be great storytellers was expressed brilliantly by filmmaker and screenwriter Cindy Chastain in an article that was part of a series about storytelling in Smashing magazine by Francisco Inchauste, titled “Better User Experience with Storytelling.”1 In part two of the series, Inchauste interviewed Chastain about storytelling as an element in experience design in business. Chastain said:

We tell stories that seek to order chaos, provide meaning and engage the emotions of our listeners. . . . Knowing the craft of narrative will help us build better stories, which will help us turn a set of lifeless features and functions into a whole experience that engages the minds and emotions of customers.

For so long, most companies have thought of the story they tell customers as their brand message. This is much too limited. As Chastain also commented:

Brand message is no longer the thing that sells. Experience sells.

If the intangible pleasure, emotion, or meaning we seek can be made tangible through the use of story and narrative techniques, we will build more compelling product experiences. And if the experience is more compelling, businesses will profit from droves of loyal, experience-discerning customers.

Without this understanding, choices about what features should be included and how they should behave seem both uninspired and disconnected. Sure, we have business goals, user needs, design principles, and best practices to draw on, but these things won’t get us to a place where a team is collaborating in the same conceptual space, let alone designing for emotion and meaning.

If we can begin to think of every engagement a customer has with us as a story, an engaging drama with a beginning, middle, and end, we will be at a great advantage in crafting experiences that are gripping and memorable and that inspire customers to share them.

What makes some stories so much more engaging than others? One element of a good story is a strong opening.

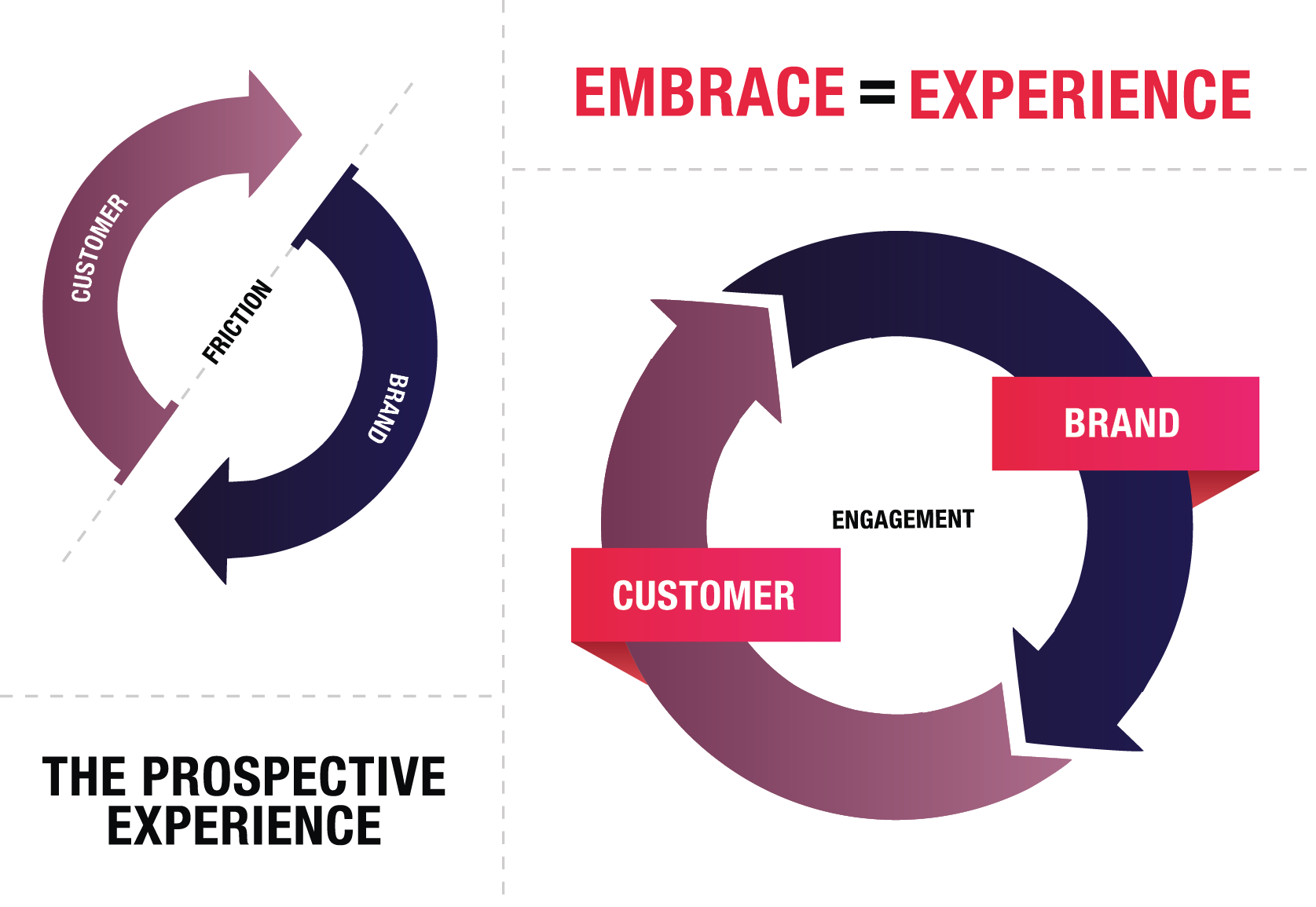

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN: THE EMBRACE

Great storytellers pull their audience in with alluring opening lines like “It was a dark and stormy night,” which drew readers into Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s novel Paul Clifford, and “When Gergor Samsa woke up one morning from unsettling dreams, he found himself changed in his bed into a monstrous vermin,” from Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis. In movies and TV dramas, viewers are often put right into the heat of action, known as in media res. In composing one of the most dramatic musical compositions of all time, Beethoven opened his Fifth Symphony with four notes that are so compelling that even listeners who have only heard the piece once would immediately recognize those notes.

In marketing, we’ve also put great emphasis on getting attention, and it’s vital. But it’s no longer sufficient.

Attention does not equal aspiration—and it’s not enough. Just because you have someone’s attention doesn’t mean you’ve engaged them. While attention can be fleeting, engagement can be long term, potentially endless. You don’t want to just get your customers’ attention, you want to embrace them.

Once you have someone’s attention, you have to shape engagement into something significant and mutually beneficial. This takes consideration, understanding, and design. It has to have meaning and direction and must feel natural.

We touched upon “the embrace” earlier, the moment when you have someone’s attention and an opportunity to do something meaningful with it, as a key moment in the steps that form the Sphere of Experience. The embrace makes you think of your interactions with customers at all touch-points in that way. In an embrace, you are holding someone, and that’s also what you want to do, figuratively speaking, with customers. An embrace is a sign of affection, respect, and support, and to be pleasing, it should feel natural and comforting. We’ve all experienced the awkward embraces in which someone smothers us in a bear hug. An embrace has to be carefully calibrated. This is a moment for enchantment.

When you design for the embrace, you design for meaning, purpose, and desirable aftereffects. The result is reciprocity. And, reciprocity is what relationships are all about.

There are two ways to affect human behavior: 1) manipulate it or 2) inspire it. We can either inspire them or manipulate them. Today, there’s far too much emphasis on manipulation. Think about how many times you’re manipulated versus inspired as a consumer. Imagine now what experiences, and customer relationships, would look like if we all designed for the embrace.

THE STORY OF THE STORY ARC

Brand storytelling is largely ineffective because rather than embracing customers we scream and holler for their attention. We also don’t build stories with good story arcs. In great stories, the drama builds up and up to a climax. And throughout, spikes of drama are plotted so that the story never becomes too predictable or boring.

This is a well-established illustration of an effective story arc, which is characterized by a number of crises that the protagonist faces, assuring regular bursts of dramatic tension. The mandate for a good story that this classic arc sets forth is as follows:

Beginning: Introduce the protagonist and the first crisis.

Middle: A series of additional crises must be confronted, each building on the last to ramp up the dramatic tension.

End: One final crisis leads to the triumphant climax, otherwise known as the denouement.

Now take a look at the typical arc of the stories most businesses tell customers.

This is the campaign model, in which we front-load the drama, putting all sorts of resources into the attention-getting opening, and way too little as the rest of the customer experience unfolds. The story dissipates and eventually fizzles out until the next campaign:

“Look at this! Look at us!”

“Don’t you wish! Join us—become like us!”

“Sorry, we have to go because we’re out of time and money. Don’t worry, though. We’ll be back with another creative campaign! And it may or may not connect the dots!”

With storytelling for experience the story doesn’t end at all. As one great tale is finishing, another is just beginning. I refer to this as pervasive or responsive storytelling. The end of one story is the beginning of another. And it’s always culturally and contextually relevant on each screen and in each network.

Pervasive storytelling assumes that you have developed not only a master story arc but also micro-arcs that overlap one another so that you are always engaging the customer in a way that’s experiential, entertaining, and empowering. These are the micro-experiences; think of them as micro-stories.

You need a good story for each moment of truth, with its own micro-beginning, -middle, and -end, and with endings that always leave them wanting more.

A great example of this was highlighted by Francisco Inchauste in Smashing magazine.2 He examined the deeper story told by the packaging and the unboxing of the Apple iPhone. To do so, he layered the classic story arc diagram over the iPhone box to emphasize the point.

The Story of the Packaging of the Apple iPhone by Kate Briggs, Akavit

Anyone who has bought an iPhone will fondly remember the drama of opening that box and unpacking the phone and its accouterments. The story unfolds with a series of mini-dramas as you work your way through the layers of packaging. The box itself is a masterfully designed product. And of course, the climax is holding the phone in your hand and beginning to explore its rich offerings. And here is where Apple continues the story.

The phone is loaded with so many goodies to test out. As Inchauste pointed out, stories are not all overtly told; they’re not all a matter of messaging. They can be embedded in a product, and, as Apple has so artfully shown, in its packaging. But they can also be embedded in every encounter a customer has with us or our products. And they can in fact be stories actually told, perhaps with video or with rich photography, or even typography. As Inchauste wrote:

There are many experiences in which storytelling is used to create a compelling message that draws users in. The stories are not always visible or apparent right away, but underneath many good experiences we can find great stories. They may appear in a series of interactions that tie into a larger story or simply in an emotional connection that we form with a product or brand.

Think of customer experience storytelling not as the art of brand messaging but as the art of engagement.

THE A.R.T. OF ENGAGEMENT

In order to hold customers’ attention and truly embrace them, you must design every encounter with three things in mind:

A: Actions

R: Reactions/interactions

T: Transactions

A: Actions speak louder than words. What actions do they hope to achieve, what outcomes do they seek, and how can you present an intuitive, native opportunity for them to do so?

R: Reactions are an emotional response to the engagement. What reaction do you want them to have, and what should follow it? How does the conversation play out? Who’s involved, why, to what extent—and what’s in it for them?

T: Transactions aren’t limited to selling and purchasing; rather, they are comprised of a series of exchanges. Engagement either brings people closer to you or pushes them away. You can ensure that they reciprocate the embrace by inspiring them to learn more about you and your brand, products, and services and to hear about the experiences of others with you as well as inspiring them to purchase.

You must design thoughtful and mutually beneficial micro-engagements throughout the whole customer journey:

Awareness

Discovery

Commerce

Usage

Support

Loyalty

1 www.smashingmagazine.com/2010/02/11/better-user-experience-through-storytelling-part-2/.

2 www.smashingmagazine.com/2010/02/11/better-user-experience-through-storytelling-part-2.

6.2

STORYBOARDING

EXPERIENCES, LIKE ANIMATION, NEED A STORYBOARD

The best storytellers create a story outline to figure out in advance how to structure the story and what experiences they will put their characters through. In movie-making, this is done through storyboarding.

Storyboards are meant to tell stories to immerse viewers in the character’s journey. Cell by cell, the story unfolds with each image bringing the scene to life. As we follow along, we’re introduced to sequence, context, behaviors, action, location through brief narrative, and simple sketches. You see and feel everything. As a result, you’re inspired because the journey is enchanting and unforgettable.

But there’s more than meets the eye with storyboards. While their purpose is to allow for the visualization of a motion picture or interactive or animation sequence, they are really meant to help everyone involved in production vet ideas and iterate and test the realness of the characters, their journeys, and the plot. More so, they test the logical and emotional impact of every step, allowing for hidden feelings to establish emotional salience. Storyboards are also an exceptional technique for prototyping meaningful customer experiences. They inspire you to figure out what experience you are putting your audience through. The process of storyboarding channels empathy. If they have a superpower, the gift of empathy would be it.

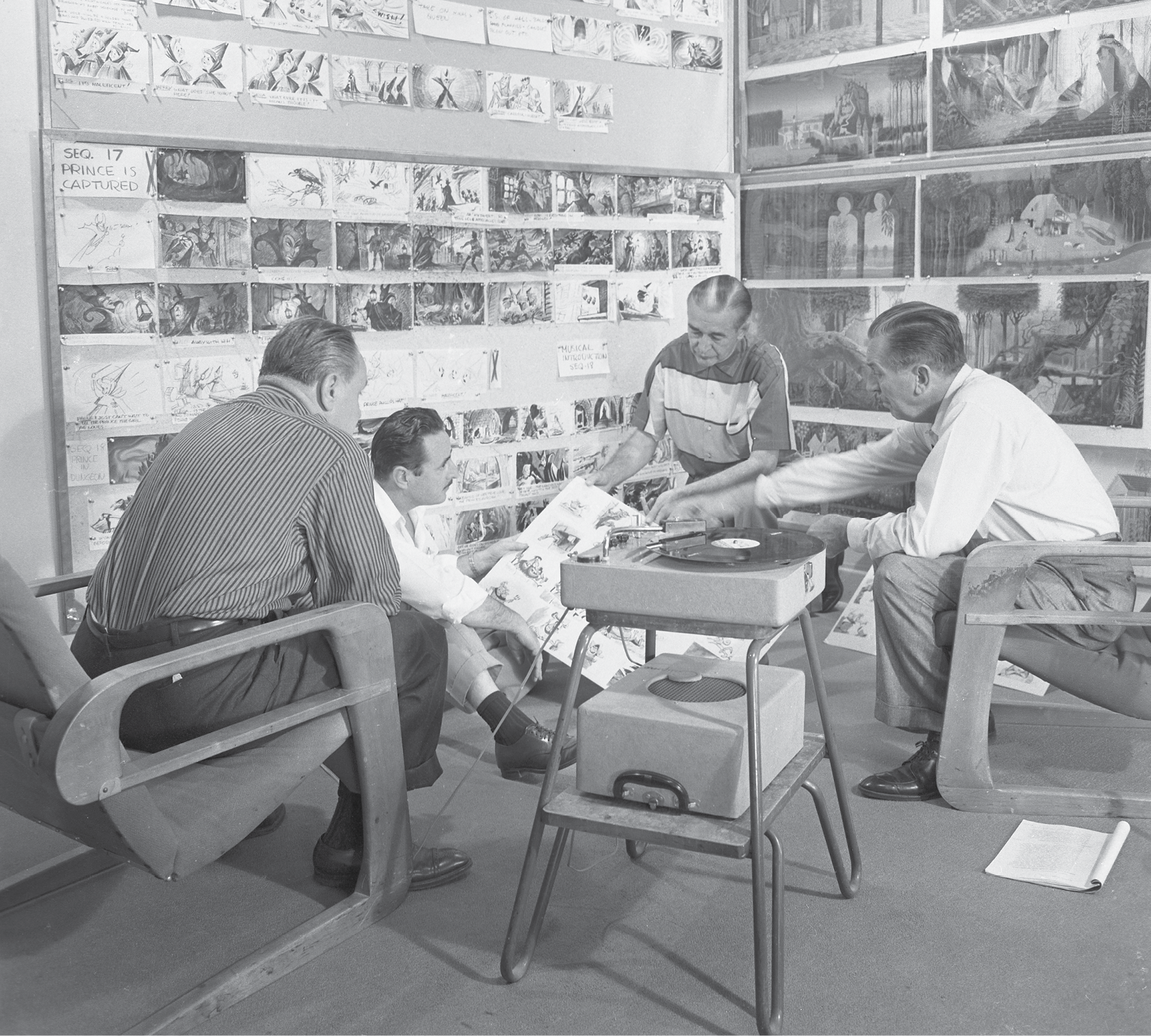

Storyboards were invented in the 1930s by an animator named Webb Smith, who worked at Walt Disney Productions. He illustrated scenes on individual sheets of paper and then pinned them up next to one another on a bulletin board to tell the story in sequence. By the early 1930s, storyboards had evolved from comic-book-like “story sketches” to elaborate drawings.2 One of the most famous uses was in the animated feature film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. Thousands of sketches were created and pinned to a wall with the production crew acting out each scene to bring it to life. They were, at the time, pioneering in both art and technology.

Walt Disney and Crew Working with the Snow White and Seven Dwarfs Storyboards1

Storyboards allowed Disney and his animators to work out all of the details of the story before expensive animation began. They facilitated the sharing of information, targeting problem solving and cross-departmental collaboration. Early on, Disney partnered story people (those with ideas) with sketch artists (cartoonists), which represented a complementary collaboration between thinkers and doers. These story artists were largely responsible for making up the content of the films. Eventually these roles combined.

Of all of our inventions for mass communication, pictures still speak the most universally understood language.

—Walt Disney

Because it is entirely concerned with actualizing a character’s emotional journey, narrative storyboarding holds incredible potential for exploring and representing the user experience and journey. By thinking through scenarios, emotions, ambitions, and narrative, we can visualize how the journey unfolds in real life in much the same way as animators storyboard movies.

Burny Mattinson, who is in story development at Walt Disney Feature Animation, certainly feels empathy, explaning:

When you’re actually drawing the story sketches, you get emotional about them yourself. You’re looking for things that have a lot of heart. You’re trying to draw that in a simple way to express what you’re feeling.

THE STORYBOARD IS THE BLUEPRINT FOR YOUR CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE AND THE WHOLE CUSTOMER JOURNEY

A storyboard is useful when it tells the story you’re trying to tell and makes that story ring true. I heard over and over again in my many conversations with animators that one of the key metrics of success is that the storyboard be rich in believability and sincerity. Believability refers to a metric based around faith and self-judgment: In my deepest heart, do I believe this? Does it feel true to my experience? The entire enterprise of Pixar filmmaking, for example, is based around the idea that if something resonates with me, it’ll resonate with you, too. It’s a kind of quantitative research that, instead of looking out, looks inside; relatability is where empathy is born.

Did you know that it takes Pixar Animation Studios roughly four years to make a film?3 They know that it takes time to get a story right. In fact, Pixar refers to the storyboard process as story “re-boarding.” They know that once you start to lay out the story, ideas for changes are inevitable and an important part of the creative process. The process of fine-tuning emotion through formal elements is the reason that animated films take so long to make and why—when the stars align—they can be so impactful. Storyboarding allows filmmakers to design just the right sequence of events to allow people to connect with ideas, turning experience into something emotionally meaningful.

MIRROR MIRROR ON THE WALL, ARE AIRBNB CUSTOMERS THE CHERISHED OF THEM ALL?

During a Christmas holiday, Airbnb co-founder Brian Chesky read a biography of Walt Disney. In the book, the story of Snow White and the importance of storyboarding in its production inspired Chesky to visualize Airbnb as way of guiding the company’s next steps.4

The company embarked upon a project appropriately named “Snow White” to visualize the entire journey for Airbnb hosts and guests, end-to-end. To do so, the team hired Pixar animator Nick Sung to help with the storyboarding process.

At Airbnb, storyboards served the exact same role as they did during the development of Disney’s Snow White. They were meant to define a long-term set of priorities for scale, moving away from transactional room rental, and toward customer experience, service, and lifestyle. In Sequoia Capitol’s blog,5 Airbnb CTO Nate Blecharczyk tells the story this way,

The storyboard was a galvanizing event in the company. We all now know what “frames” of the customer experience we are working to better serve. Everyone from customer service to our executive team gets shown the storyboard when they first join and its integral to how we make product and organizational decisions. Whenever there’s a question about what should be a priority, we ask ourselves which frame will this product or idea serve. It’s a litmus test for all the possible opportunities and a focusing mechanism for the company.

Airbnb Personas on Display at Company Headquarters, Photographed by Hui Yi

Before the company even visualized the journey, it first had to understand who the people were who would define the Airbnb community: its hosts and guests. As we reviewed earlier, persona development is a wonderful way to humanize the very people you wish to embrace. In this case, the company identified six different characters: 1) Cassandra (Casual Host), 2) Paul (Pro-Host), 3) Stephen (Semi-Pro Host), 4) Adrienne (Authentic Travel), 5) Veronica and Rick (Vacation Rental Travelers), and 6) Holly and Henry (Hotel Travel). Each is described and humanized in ways that not only enliven their personality but also their behaviors, expectations, aspirations, and so on.

These frames remind us to think holistically about the Airbnb experience. Use them to consider important touch-points, prioritize strategy, address customer needs, and remember the real life context of work.

As you explore Snow White, consider:

What is the person thinking or feeling in each frame?

What motivates these characters to progress in their journeys?

What opportunities exist to improve or enhance the experience for them?

How does your work influence what the character feels, knows, thinks, decides, or does?

The team explored and played out the message, story, and the feeling of the characters. Also in the process: They understood core concepts. The process brought the team together across functions and roles. As a team, they were united in their mission and purpose. They came together by finding the moments and accenting the key emotional points that are vital to experiences in every step of the journey. This is especially important because, as the team realized, the experience didn’t begin just upon arrival at an Airbnb home. It actually began with travel, including many real world elements that lie out of the realm of control for Airbnb.

By creating storyboards of the experiences you want to offer, it will similarly spur your team’s creativity and allow you to make refinements or even discover whole new ideas. Storyboarding continues to be used by product producers, marketers, engineers, UX designers—even members of the finance department. It was also used to completely rethink the Airbnb recruiting process, using the emotive states of applicants as the basis for developing best practices, alleviating pain points, and offering support.6

Project “Snow White” on Display at Airbnb HQ, Photographed by Hui Yi

Sample Storyboard Developed by Brian Solis to Highlight One Moment of Truth, Using Nespresso as the Hero

As one company represented shared with Fast Company, “We’re going to figure out a way by using storyboards to migrate ideas from every single person in the business, through a decision funnel so that actually all the brilliance in the business is reflected in the product.”

STORYBOARDING SCENARIOS

Storyboards possess a unique capacity for dramatizing ideas. But all too often, there are those who misinterpret storyboarding as simply a means of visualization. From what story artist Nick Sung has witnessed in his tech and branding adventures, the process is as follows: a team does a lot of brainstorming, lays out a framework, someone draws it, it’s shared, and that’s that. In a conversation about his experience with what brands get right and wrong in storyboarding, he shared with me,

While these boards encourage designers to think from a user-centered perspective, they only achieve this cursorily. As images without particular acuity, they reveal nothing in particular through their rendering.

I fell into the same trap. While I was writing this chapter, my editor recommended that I attempt to develop a storyboard using a real world moment of truth. For those coffee lovers on the go, here’s an all too common scenario.

Our hero has run out her favorite coffee. To design an incredible experience the experience architect explores all sorts of solutions, looking for those that will exceed expectations: in this case, an on-demand delivery service.

Even though I visualized the scenario, I didn’t really explore the story, aspiration, and emotion to help you better understand the customer or her world, to set the stage for creativity.

Of primary importance, as Nick taught me, is the question: What is this really about? Or, what is the drama in this situation? These questions aim at the heart of a moment, and attempt to discern the emotional and tactical motivations of an action. Life is not neutral, and products don’t win within a vacuum. Asking these questions is the difference between:

I have no time to run to the Nespresso or grocery store and I need coffee now!

I’m harried and can barely take care of my basic needs.

The former describes the situation; the latter describes the emotional state. The former speaks to the need for coffee and a time-saving service; the latter speaks to the need for relief and a service that is not only time saving, but—potentially—broad in scope, and perhaps demonstrative of a longer standing problem that could use solving.

Storyboarding is valuable in two key forms: 1) It is a process of conjecture, critique, and connection; a testing ground for the emotional resonance of ideas and the narrative structures that engender and undergird those resonances. 2) Storyboard is the resulting form of that exploration: a working model. The process is valuable because it allows the surfacing and testing of insights. The model is valuable because it allows for a critique of both the assumptions leading to design decisions and the possible execution of those decisions.

The development of a really robust storyboard sequence includes the following processes:

Ideation: Concept development, thematic development.

Modeling: The structuring of narrative and visual and cinematic ideas.

Critique: Often done in collaboration; a vetting of the emotional resonance

analysis of the narrative and visual structures toward the production of—not just a great sequence—but a great sequence within the context of the larger film.

Iteration: Adjustments based on the critique, to make the sequence increasingly powerful and resonant.

Additionally, storyboards rely on a command of the following elements:

Visual language: The capacity to convey ideas and emotions through visuals.

Point of view: One’s thematic thesis, and the perspective taken by the author.

Story sensibility: Natural inclination toward certain kinds of material (strengths + biases).

Sincerity and belief: You don’t tell a joke if you don’t think it’s funny, right?

The point of the work is to define and then refine the emotional connection between each moment of truth and ensure a desired experience through the customer journey. Your work should initially focus on the moments of truth and the context that leads up to them that define:

Discovery

Consideration

Transaction/purchase

Service/support

Satisfaction/retention

Loyalty

Ultimately, you want to create the story for all of the experiences at every touch-point, including, at a minimum:

State

Purpose

Design

Welcome/onboarding/unboxing

Usage of product or service

Product help or support

Follow-up customer touches

Re-engaging customers/retention

Rewarding experiences and customer behavior

STORYBOARDS NEED STORYTELLERS

If I could add just one more thing to the list, it would be to bring storyboards to life with stakeholders through narrative, voice, enthusiasm, dramatics, and other forms of stagecraft. Walt Disney was a master of storyboarding and he was also a master at storytelling. Walt crafted stories to inspire his employees, convey his vision, and make it come alive every step of the way.

During the winter of 1934 Walt rounded up his top animators on a soundstage. He stood in the front, only lit by a single spotlight. This is when he announced that he was going to launch an animated feature. Walt continued to tell the story of Snow White, acting and assuming the characters’ mannerisms, imitating their voices, and allowing his animators see exactly what he was envisioning. All together this performance took three hours. Through his love for animation he realized that telling a story can be a powerful tool when needing to focus an organization on a particular project, problem, or when needing to release the power to dream. Walt believed dreams could drive change.7

Before you turn to the next chapter, I want to share one last storyboard example. In the spirit of Walt Disney, I am inspired to share my own project “Snow White” with you. Upon completing the draft of this chapter, I partnered with Nick Sung, who now works as a consulting story artist in what he refers to as Narrative Design Strategy. Together, we developed a storyboard that reveals the inspiration of X and the journey I hoped we would go through together. Nick proved to be an invaluable advisor. His passion for storyboarding shaped this chapter and opened my eyes to new possibilities.

1

2

3

4

Let’s walk through each frame to get the storyboard behind the making of the book. It was designed with you in mind and you, therefore, are the hero in this journey.

1. CATALYST:

Sola and her team are tasked with leading change inside the company. Executives are out of touch with digital customers. They’re told to figure it out but it’s clear . . . the mandate is to increase sales and add shareholder value. They bring in expert after expert but no one seems to be able to guide Sola on the steps to actually take.

2. SEARCHING:

Searching for resources, she openly considers a variety of approaches to experience design. She reads blog posts and articles. She travels around the country to attend conference after conference. Sola becomes increasingly frustrated. “Everyone is saying the same thing and nothing at all,” she tells her colleagues back at the office.

But then someone tells her about “X” and the work that Brian Solis has been doing over the years to empower people to become change agents. “This is it! Someone actually gets me!,” Sola cheers.

She reads and re-reads. She continues with additional online research. She assembles a plan and organizes it into a timeline. She realizes the first thing to do is understand the customer and the customer journey.

3. TRIAL:

Led by Sola, the team is introduced to a new methodology, which challenges and invigorates them. She walks them through a storyboard that shares the story of one such digital customer journey. Everyone can easily see holes in the company strategy. They can feel that their customers too have feelings.

The entire process is a lattice of emotion that takes everyone on the customer journey. “It’s so easy to focus on our product, but it’s all about the user and their aspirations and real life context,” Sola’s teammate exclaims.

4. VALIDATION:

The hard work and empathy pay off. Little by little, they demonstrate success. Sola proudly reports the group’s success to the company. Change is underway!

1 © Disney.

2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BSOJiSUI0z8.

3 http://siliconprairienews.com/2010/10/josh-cooley-gives-an-in-depth-look-at-pixar-s-creative-process/.

4 www.fastcompany.com/3002813/how-snow-white-helped-airbnbs-mobile-mission.

5 https://www.sequoiacap.com/grove/posts/ezem/visualizing-the-customer-experience.

6 www.hci.org/lib/airbnb-hypergrowth-recruiting-story-holistic-automation-streamline-process-and-increase.

7 Capodagli & Jackson, 2001, p. 16, https://kashinterest.wordpress.com/2012/09/29/walt-disney-the-visionary-inside-the-bee-pollinating-his-workers-to-greatness/.