9.0

THIS IS WATER

all business is personal

Your journey with this book is nearing its end, but hopefully this is just the beginning of another journey for you, into the exciting and rewarding world of experience architecture. I hope that after you start to apply what’s been presented here, you will share your experiences with me. If you share your story, I will share it with others, and we’ll all continue this journey together. You can reach me here: [email protected].

Before you go, I’d like to introduce you to Erik Davis, a writer, scholar, journalist, and public speaker who has written interestingly about experience design. In 2001, Davis predicted that we were entering an Experience Design2 era, and he poetically described experience as “that evanescent flux of sensation and perception that is, in some sense, all we have and all we are.”

I know it won’t be easy, but I hope you will keep thinking about what we can do when we invest in understanding and appreciating others’ existing and desired sensations and perceptions. Doing so will not only greatly improve the experiences of your customers, but also your own experiences in serving them and beyond. Davis wrote:

By recognizing that the material that we are now focused on is not technology but human experience itself, then we take a step closer to that strange plateau where our inner lives unfold into an almost collective surface of shared sensation and reframed perception—a surface on which we may feel exposed and vulnerable, but beginning to awake.

All business is personal, and I want to make this book more personal for a moment, sharing some words that I have been holding onto while writing this book:

The really significant education in thinking . . . isn’t really about the capacity to think, but rather about the choice of what to think about. But most days, if you’re aware enough to give yourself a choice, you can choose to look differently.3

These words were spoken by the late author David Foster Wallace as part of his 2005 Kenyon College commencement speech, titled “This Is Water.” It was the only public talk he gave about his views on life. The speech was so powerful that it was eventually released as a posthumous book, This Is Water: Some Thoughts, Delivered on a Significant Occasion, about Living a Compassionate Life. In it, he told a short tale of two fish:

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?”

Wallace’s speech felt more like an intimate conversation between parent and child, mentor and student, or idol and fan than a commencement speech. It was personal. And he wanted his audience to take it personally. He wanted to remind us to be human, to be in the moment, and to appreciate the moment to make it matter.

He posed the challenging question, “How do we get ourselves out of the foreground of our thoughts and achieve compassion?” He wanted us to recognize that how we see life and how we live life are about choice and perception. We should always try to be aware, he suggested, of the water we’re all swimming in:

[T]he real value of a real education [has] almost nothing to do with knowledge, and everything to do with simple awareness; awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, all the time, that we have to keep reminding ourselves over and over: This is water. This is water.

Doing so requires that we find ways to broaden our perspective and get out of own minds, to train our senses on other people’s hopes and fears and joys—to get outside of ourselves. Wallace forthrightly shared:

[E]verything in my own immediate experience supports my deep belief that I am the absolute center of the universe . . . there is no experience you have had that you are not the absolute center of. The world as you experience it is there in front of you or behind you, to the left or right of you, on your TV or your monitor. . . . Other people’s thoughts and feelings have to be communicated to you somehow.

This is the fundamental mission of experience architecture—to help us see things through others’ eyes, to feel what they feel, and hear the thoughts they don’t speak. The fact that this is so difficult to do is why experience design requires an architect. I hope it’s you. I hope you go on to make a dent in the experience universe. We need you.

X

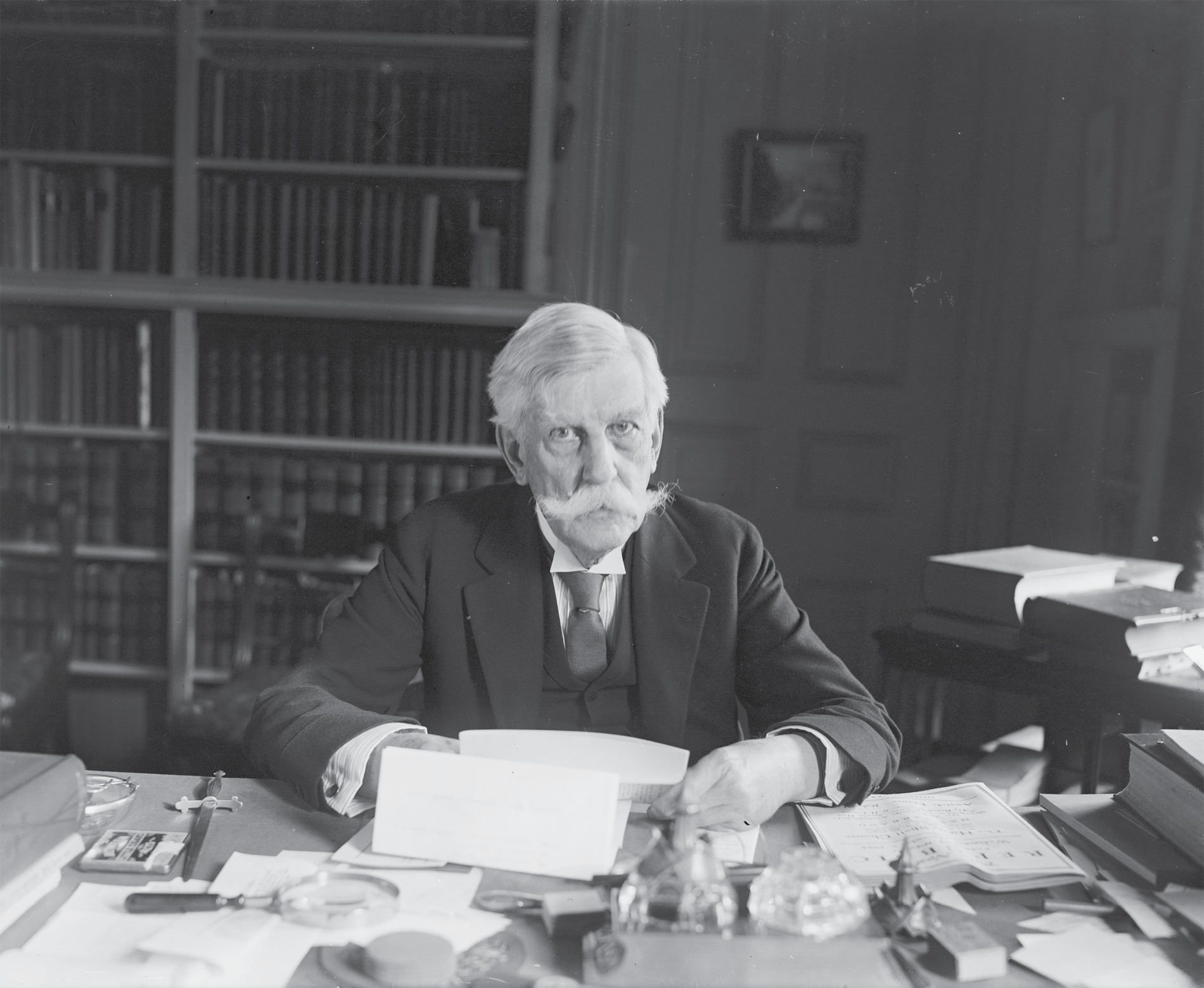

A mind that is stretched by a new experience can never go back to its old dimensions.

—Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

1 Photo courtesy of Steve Rhodes: https://www.ickr.com/photos/ari/88166765.

2 www.academia.edu/11656018/Experience_Design_And_the_Design_of_Experience_.

3 http://web.ics.purdue.edu/~drkelly/DFWKenyonAddress2005.pdf.