4.0

DIGITAL FIRST

TO DESIGN EXPERIENCES YOU MUST EXPERIENCE THE JOURNEY FOR YOURSELF

You’ve got to start with customer experience and work back toward the technology.

—Steve Jobs1

In 2003, Bernd Schmitt, a professor at Columbia Business School in New York, introduced “Customer Experience Management” as “the discipline, methodology and/or process used to comprehensively ‘manage’ a customer’s cross-channel exposure, interaction and transaction with a company, product, brand or service.”2 It’s time to move beyond the concept of managing to that of designing.

These days you want to define and enliven experiences for customers—but not just react to or simply manage them. This process is defined by a strong emphasis on innovation as a competitive differentiator—and, crucially, a value proposition to customers.

This design process must start by asking, Do you really know the quality of the experience you’re currently offering? Have you gone through the experience personally, across multiple devices and real-world scenarios, to see and feel what it’s like as a digital customer to do business with you? You might be in for an unsettling surprise.

THE THREE Ds OF CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE

In November 2005, Harvard Business School published “The Three Ds of Customer Experience” by James Allen, Frederick F. Reichheld, and Barney Hamilton.3 These “three Ds” were inspired by a Bain & Company survey that looked at 362 companies and found that 80 percent believed that they were delivering a “superior experience.” But when they asked customers of these companies about their own perceptions, only 8 percent felt that this was true. So Bain attempted to understand what set the elite 8 percent apart from the others.

The team found that the elite take “a distinctively broad view of the customer experience.” The other 92 percent, however, “reflexively turn to product or service design to improve customer satisfaction.”

The elite tended to pursue three imperatives simultaneously:

1. They design the right offers and experiences for the right customers.

2. They deliver these propositions by focusing the entire company on them with an emphasis on cross-functional collaboration.

3. They develop their capabilities to please customers again and again—by such means as revamping the planning process, training people in how to create new customer propositions, and establishing direct accountability for the customer experience.

THE 3Ds

D1 = Designing the correct incentive for the correctly identified consumer, offered in an enticing environment

D2 = Delivering the desired experience by focusing the entire team across various functions

D3 = Developing consistency in execution

To implement the 3Ds requires every strategist in every organization to recognize that they are not as customer-centric as they could be.

DO YOU REALLY KNOW WHAT YOUR CUSTOMERS ARE DOING, THINKING, AND FEELING?

Answering this question is the first step toward identifying and ultimately mapping a blueprint for the connected customer journey. One methodology for doing so is customer journey mapping. Done right, customer journey mapping is an opportunity to learn, not assume, how customers behave, where they go and why, and which devices they use in a variety of scenarios and a variety of contexts.

To improve your customer experience offerings the two most basic questions you have to answer are:

1. What is the experience our customers have today?

2. What could or should it be tomorrow?

Through a rigorous customer journey mapping process you’ll find many gaps between desired experience and reality, and those are your opportunities to compete for customer loyalty and advocacy in powerful new ways.

The process of journey mapping is critical in experience architecture. It forces you to ask questions like:

1. Have you defined the experience you want customers to have before, during, and following transactions?

2. Are your owned pages discoverable, usable, and adaptive/responsive to screens/devices and browsers?

3. If most connected customers are starting their journey on the smart phone, can they finish it using the same device?

4. If they must multiscreen, is context applied to continue the journey seamlessly?

5. How are you weaving in peer experiences from outside networks to win your customers over in every moment of truth?

6. Is there a strategy for fostering and rewarding shared experiences to influence impressions and actions of their connected peers?

No experience work you do can be complete or relevant without completing this process. Going through the experience of your customers—how they navigate, on which devices, in what contexts, and to what things—reveals the quality of your experience at all touch-points.

Don’t leave it to agencies or consultants to do this behind the scenes. You have to feel it.

MAKE IT DIGITAL FIRST

Asking the question, “What would my digital customer do?,” is the first step toward creating a blueprint for a rich connected customer journey. These days, 67 percent of the buyer’s journey is done digitally,4 and growing. Yet most journeys are still a hodgepodge of legacy touch-points governed by aging methodologies and systems duct-taped together by generations of different technologies.

At Altimeter Group, I surveyed executives and digital strategists to learn about the state of digital transformation. As you can see in the graphic here, I learned that 88 percent of the companies I surveyed were at the time undergoing a formal digital transformation effort to pursue the digital customer. Clearly almost every business believes in the importance of investing in the digital customer experience.

At the same time I found that only 25 percent had actually mapped out the digital customer journey. Said another way, 88 percent are investing in digital transformation but only 25 percent really know why. I also learned that 42 percent haven’t even studied the digital customer journey. Yikes!

UNDERSTANDING THE DYNAMIC CUSTOMER JOURNEY

Customer journey mapping yields a new understanding of how to create delightful experiences that are seamless and native to the screen and the context of the engagement. Companies must be asking the following key questions:

What uniquely defines our customers?

What is different about how digital customers undergo their customer journey versus traditional customers?

What touch-points do they frequent? How do they use them, and with what devices?

What are their expectations? What do they value? How do they define success?

How are they influenced, and by whom? How and whom do they in turn influence?

Companies that have committed to the process have reaped great benefits.

THE BEAUTY OF MAPPING THE CUSTOMER JOURNEY

In 2012, Sephora undertook a significant CX makeover to define the ideal customer experience and how it would play out in digital and real-world channels—including in-store engagement—with the aim of their complementing and optimizing one another.5 The world-renowned beauty retailer invested in an entirely new shopping experience that integrates mobile, social, and in-store activity. The process began with mapping the customer journey. Bridget Dolan, vice president, Sephora Innovation Lab, explained that the company outlined a complicated path where customers may or may not follow any one route. “Sephora is such a multifaceted experience that there’s not one path or map you could create,” Dolan said. “We think of it as optimizing experience by experience. We look at each piece and how it interrelates.” This process should also be ongoing. Dolan continued, “We’re constantly surveying and watching what clients are doing to use different technology in-store, online, and on mobile.”

INTUIT SIMPLIFIES THE BUSINESS OF LIFE BY STUDYING THE DCX6

Intuit creates business and financial management solutions that simplify the business of life for small businesses, consumers, and accounting professionals.7 The company closely studies the relationship between customer technology usage and path to purchase. They start with a simple but integral question: “Based on technology adoption, what is our customer’s path to purchase?” To be successful, the team looks beyond demographics and invests in looking at psychographics (i.e., shared behaviors and interests) to create accurate buyer personas and better understand the new customer journey. They know who their customers are because they have studied a “day in the life of” to understand the challenges they face and as well as their aspirations and goals.

LEGO INVESTS IN THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF CUSTOMER DECISION-MAKING

In LEGO’s work, the company learned that there were often two journeys: one for those who love LEGOs and another for those who purchase them on behalf of someone else. As a result, LEGO mapped two customer journeys, one for children and one for parents. Insights from each help the company focus on developing touch-points within each journey while also ensuring synergy and intersection between them.

Lars Silberbauer, global director of Social Media and Search at LEGO, shared the advantages of the company’s approach:

Shoppers are not the same as consumers. Consumers are usually kids without the ability to buy things. At the same time, we want them to tell their parents, and we want their parents to have a good experience as they shop.

DISCOVER DISCOVERS A NEW PRODUCT THAT CATERS TO DIGITAL CUSTOMERS

Customer journey mapping can also lead to insights that contribute to serendipitous product and service innovation. Our discussions found that studying customer expressions along with journey mapping revealed common customer questions, interesting ideas, beneficial product opinions, and competitive sentiment.

When credit card provider Discover invested in journey mapping it unearthed the opportunity to offer a new type of card, called the Discover it® card. When it comes to introductions, Discover it® is in elite territory as it offers some industry-leading introductory rates on purchases and balance transfers.8 It seems to resonate quite well with a new generation of consumers, earning high marks for its services, benefits, and incentive programs.

BUILD THE RIGHT TEAM FOR THE JOURNEY

In order to do the right job of mapping the customer journey, you must have the right people on your team. The work requires expertise in human-centered design and what I like to call data artistry. But just what the role of these experts should be, and how they should be contributing to the process, is unclear to many people in experience design in part because the terminology is such a riot of acronyms—UCD, HCD, UX, and so on. So let’s take a good look at what these specialists should be doing and how they can make such a contribution to much more effective experience architecture.

1 Steve Jobs Keynote Presentation, World Wide Developers Conference (May 1997). See www.complex.com/pop-culture/2012/10/steve-jobs-quotes/starting-with-the-customer.

2 Bernd H. Schmitt, Customer Experience Management: A Revolutionary Approach to Connecting with Your Customers (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2003, ISBN 0-471-23774-4).

3 James Allen, Frederick F. Reichheld, and Barney Hamilton, “The Three Ds of Customer Experience,” in Working Knowledge for Business Leaders (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School, November 7, 2005).

4 Sirius decision.

5 www.briansolis.com/2012/09/sephora-gets-a-digital-makeover-to-attract-connected-customers/.

7 www.intuit.com/company/press-room/press-releases/2014/SmallBusinessEmploymentTakesAnotherStepForward.

8 www.reviews.com/rewards-credit-cards/discover-it/.

4.1

DESIGN FOR HUMANS

PEOPLE ARE PEOPLE: PUTTING THE PEOPLE IN P2P

What people seek is not the meaning of life but the experience of being alive.

—Joseph Campbell

As the sample journey maps presented earlier show, designing experience takes just that: both design and experience—experience that you and your team may not have yet. You will need to either bring people on staff who do, or partner with a firm. Capital One acquired Adaptive Path because to compete for tomorrow’s consumer, you need designers who see what you don’t or can’t. If you can’t hire top talent, buy it!1 Capital One said Adaptive Path would help it to “push our thinking” as it tries to “reimagine banking.”

The fundamental skill that most companies must bring into their internal operations and make the guiding determinant of all of their experience creation work is referred to as human-centered design (HCD).

Another, perhaps more familiar term, is user-centered design (UCD), and frankly, discussion of design in business has become something of an alphabet soup of acronyms that have muddied understanding. Let’s consider the differences between UCD and HCD, whether there really should be any, and why the elements of each should be at the core of what you need to be doing.

UCD is often discussed in terms of the design of technology interfaces. It’s more than that. The Usability Professionals’ Association2 defines UCD as an approach to design that grounds the process in information about the people who will use the product. Said another way, UCD is a product and service creation process that puts the needs, wants, and limitations of end users at the center of decision making at each stage of the design process. The aim of UCD is to create applications or products that are not only easy to use but offer users added value above just basic functionality.3

That sounds great, right? So what’s the need for more lingo by introducing the notion of human-centered design? The limitation of UCD is that designing for a “user” usually leads to an overemphasis on simply optimizing the characteristics of the product, system, or service based on a set of preconceived plans. Susan Gasson is associate professor, Information Systems at Drexel University College of Computing and Informatics.4 Gasson studies the design, use, and impacts of digital technologies for boundary-spanning collaboration. In her work comparing HCD and UCD published in 2003, Gasson found that “user-centered system development methods fail to promote human interests because of a goal-directed focus on the closure of predetermined, technical problems.”5

Experiences are human and experiences are also more than products or designs.

ENTER HUMAN-CENTERED DESIGN

HCD takes a step back to see the whole person, not merely thinking of customers as users of your product, but rather in the wider context of living their daily lives. A fundamental principle is that we can learn a great deal about how to better serve people by understanding how they spend their time not only with our products, but in all other walks of life. By getting to know them as well-rounded people who do all sorts of things other than using our products, we can identify opportunities to appeal to them and serve their needs that we would not otherwise come up with. We’ll see a couple of great examples of this in the next chapter.

NOT JUST SERVING PEOPLE, HELPING THEM CHANGE

The more we are taking into account the whole person when we examine our customer experience ecosystem, the more we can discover how to help them not only meet their current needs, but make changes that improve their lives in unexpected ways. Steve Jobs was a maestro at this. When he got a glimpse of a graphical user interface and the computer mouse, he understood how they could help not only do computing faster, but break down the barrier between the alien world of the digital computer and the familiar world of tools that fit our hands and their particular talents well. He did this over and over again.

Through consistently understanding the deeper desires of people and how innovation could help them improve their lives, his Apple products have substantially changed the relationship of so many people to technology.

Michael Shanks is an archaeologist at Stanford University in California who explores transformative design. He featured a fascinating interview on his site with Banny Banerjee, director of the Stanford Design Program,6 in which Banerjee discussed how good design can influence changes in people’s behavior:

Our behavior is deeply influenced by the norms and frameworks that surround us and design can be used to create systems and experiences that work with an underlying understanding of human behavior and cause people to fall into entirely new patterns of behavior.

Banerjee sees this as a golden opportunity for companies who bring in the right design talent:

Because behavior can be influenced—not just observed—it provides an important opportunity [that is] perhaps best addressed with design. Uniquely trained to simultaneously consider human factors, technology and business factors, designers can help identify a behavioral goal . . . and then work from that to employ the best systems, ideas, experiences, and technologies to enable alternate realities in the future.

Shanks also tells the story of a time when Leslie Witt of IDEO, the influential Silicon Valley design firm, visited Stanford University to talk to students about how design plays a role in changing behavior.7 Witt said that most people want or need to change. But unless someone helps them or breaks down the journey to change into actionable, approachable steps, they see change as something for everyone else. Witt sees this as a market opportunity. I see this as a baseline for experience architecture. It has the capacity to give people the tools for changing their lives.

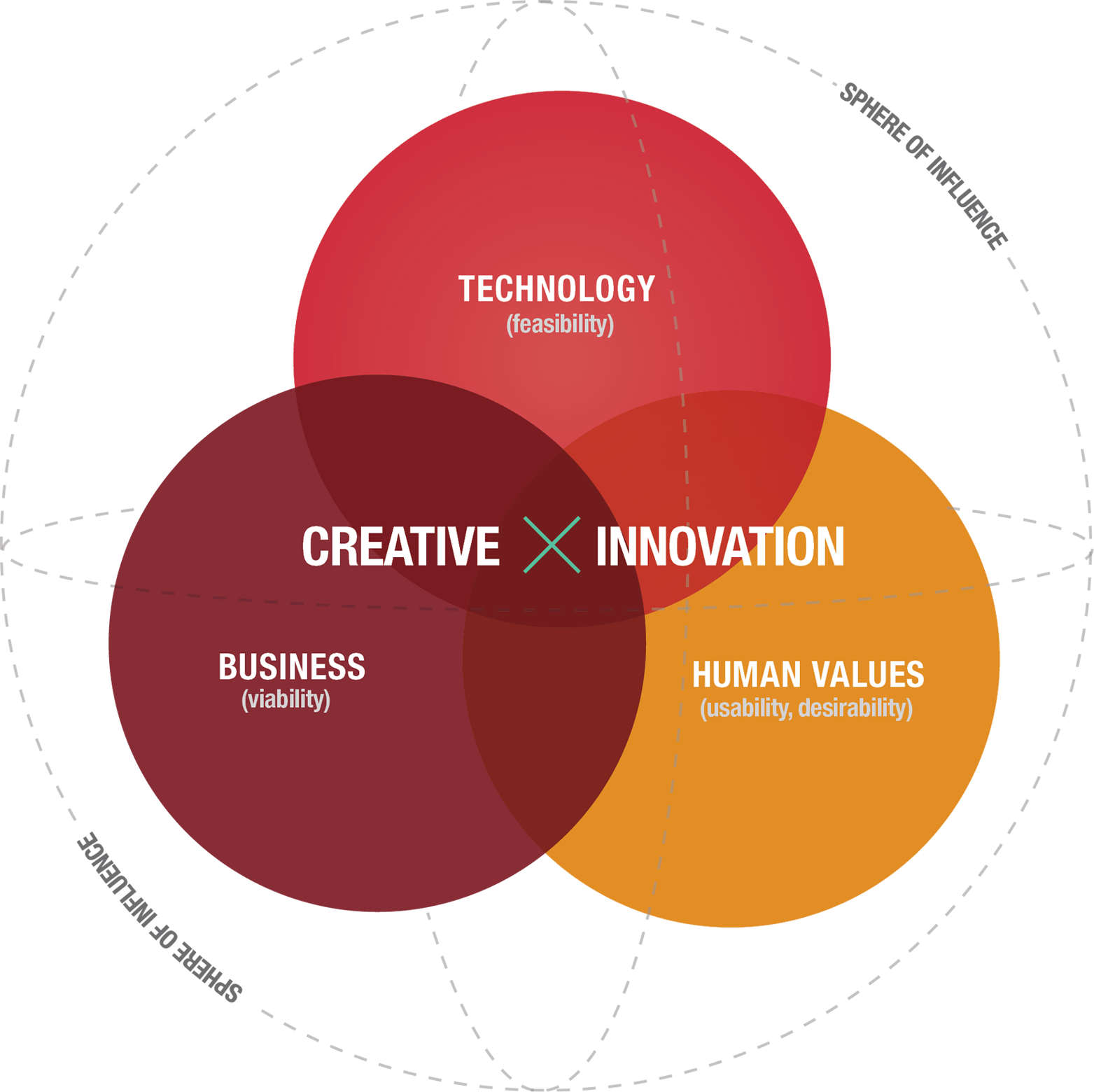

IDEO developed a powerful graphic that helps to keep the mandate of incorporating a sensitivity into human wants and needs at the center of the product and service development process. I modified it to include aspects from the X framework.

CREATIVE x INNOVATION

Technology (feasibility)

Business (viability)

Human values (usability + desirability)

Sphere of experience (shared experiences)

THE FULL SET OF HUMAN FACTORS

In order to keep this whole-human focus in designing your experience ecosystem, your team must tell the story of its inhabitants, your customers and stakeholders, and how you see them living in this world in their preferred ways. You must describe the community in which they live, what life is like, their rituals and aspirations, and their challenges and successes. Here is a checklist of factors that must always be taken into account:

Story: The narrative of the product, how it relates to the brand, and the consumer’s role in the overall journey. How do people become part of the story their way?

Design: The intended styling and aesthetics of the product and how it appeals to consumer senses of touch, smell, sight, sound, and taste.

Capability: Providing customers with the ability to do something they hoped to accomplish—or didn’t know they could do until your product.

Sensation: The architecture of how a brand and product should make customers feel—not just through marketing, but through product design, ownership, support, and advocacy. This is the stage of emotional bonding with the product as perception unfolds along the desired narrative and intended impression you’ve created. (sight, sound, touch, smell, taste)

Expression: How the product aligns with the personal or professional lifestyle of the customer. Your product can serve as an extension of who they are and help them become part of a community that means something more than the individual or the product alone. What is the experience you want people to share? How does it become part of them?

Cognition: The result of the intended experience and how people learn to think about it in relation to their everyday life and what their life can become.

WHAT IT TAKES

The International Standards Organization, an independent, nongovernmental membership organization and the world’s largest developer of voluntary international standards, identifies six major ways to humanize design:

1. The adoption of multidisciplinary skills and perspectives (more than any one function, experience design crosses borders and brings people together under a common vision).

2. Explicit understanding of users, tasks, and environments (people, behaviors, context, preferences, goals/aspirations).

3. User-centered evaluation driven/refined design (everything from products to interfaces to the journey to engagement are centered in human engagement).

4. Consideration of the whole user experience (experience architecture).

5. Involvement of users throughout design and development (don’t assume; engage).

6. Iterative process (refine, improve; customers and their needs and expectations are always changing).8

To do all of this takes having the right people on the bus, as Jim Collins would say. So now we’ll take a look at the core personnel of HCD.

1 www.americanbanker.com/issues/179_193/capital-one-seeks-creative-spark-with-purchase-of-design-rm-1070379-1.html.

2 http://uxpa.org/resources/denitions-user-experience-and-usability.

3 www.usabilitynet.org/management/b_overview.htm.

4 http://cci.drexel.edu/faculty/sgasson/.

5 S. Gasson, “Human-Centered vs. User-Centred Approaches to Information System Design,” Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application (JITTA) 5, no. 2 (2003): 29–46.

6 www.mshanks.com/2010/01/13/on-design-and-changing-behavior/.

7 www.mshanks.com/2010/01/17/design-and-behavior/.

8 www.iso.org/iso/home/about.htm.

4.2

BX + UX + CX = X

THE FUTURE OF CX IS UX

UX has come up quite a bit. It’s important. Any company that doesn’t have a user experience design (UX) specialist on the customer experience team must bring one in; UX expertise is vital to the process.

We referenced transportation engineering earlier in the book. What transportation engineering is to urban planning, UX is to customer experiences. In fact transportation engineering is not unlike UX, which encompasses all aspects of a consumer’s interaction with the company, its services, and its products.1

In the business of user experience design, the Nielsen Norman Group is among the world’s best. Co-founder Donald Norman is widely regarded for his expertise in the fields of design, usability engineering, and cognitive science. He is also highly regarded for his books on design, especially The Design of Everyday Things.2 Much of Norman’s work involves the advocacy of user-centered design.

For this discussion, I’d like to replace user with human in describing the practice. To be effective in human-centered design, Norman suggests we need an authoritative strategist and designer who can examine the suggestions from colleagues and even people themselves and evaluate them. It is essential not only to consider requests thoughtfully but to have the expertise to ignore some requests, even if they seem commonsensical or seem like low-hanging fruit. Paradoxically, sometimes the best way to satisfy people is to ignore them.

Every business needs at least one expert UX designer for crafting its experience ecosystem and protecting and optimizing it over time. UX design encompasses all aspects of the end-user’s (or person’s) interaction with the company, its services, and its products. As UX luminaries Nielsen and Norman once wrote, “The first requirement for an exemplary user experience is to meet the exact needs of the customer, without fuss or bother. Next comes simplicity and elegance that produce products that are a joy to own, a joy to use.” This is especially true if those needs aren’t yet voiced by people.

Many companies do employ UX professionals, but I’ll make a sweeping generalization here and say that they’re usually underutilized and underappreciated. This is in part because UX is so often confused with UI (user-interface design) or the design of technology for usability.

UX is about much more than optimizing layouts, product designs, and site navigation. While those are all part of UX, such issues represent merely a sliver of the purview of the discipline. It’s important. That’s why Capital One acquired Adaptive Path. So let’s take a moment to better understand the role of UX and how it is different from usability and UI. It all applies to your work in experience design.

USABILITY

Usability is the ease with which customers can use and learn about a human-made object. Usability also refers to methods for improving ease-of-use or engagement during the design process.3

Jacob Nielsen, Donald Norman’s partner in the Nielsen Norman Group, codified the elements of usability this way:

Learnability: How easy is it for users to accomplish basic tasks the first time they encounter the design?

Memorability: When users return to the design after a period of not using it, how easily can they reestablish proficiency?

Errors: How many errors do users make, how severe are these errors, and how easily can they recover from the errors?

Utility: This refers to the design’s functionality—does it do what users need?

Useful: Is it something that users want?

Usability testing is a must in all design, but before that, you must consider the needs, expectations, and desires of users to be sure you’re serving them. As Nielsen observes,

It matters little that something is easy if it’s not what you want. It’s also no good if the system can hypothetically do what you want, but you can’t make it happen because the user interface is too difficult. To study a design’s utility, you can use the same user research methods that improve usability.

DEFINITIONS

Utility = whether it provides the features you need

Usability = how easy and pleasant these features are to use

Usefulness = usability + utility

UI: USER INTERFACE DESIGN

As for UI, it refers specifically to the design of the means in which a person controls a software application or hardware device. A good user interface allows users to interact with software or hardware in a natural and intuitive way.4

For example, Apple’s new smart watch required the development of an entirely new UI that brought the familiarity of iOS on iPhones and iPads to an entirely new (and smaller) screen and ultimate experience. Apple introduced a digital crown, a winding mechanism on the side of the watch, which helps users navigate in a way similar to the dial on the original iPod. In short, UI is a sub-practice of UX.

UX: USER EXPERIENCE DESIGN

UX has incorporated the insights, principles, and methods of both usability studies and UI, and has added practices from other disciplines as well. A good basic definition was given by Lauralee Alben in her 1996 book, Quality of Experience:

[UX] covers all the aspects of how people use an interactive product—the way it feels in their hands, how well they understand how it works, how they feel about it while they are using it, how well it serves their purposes, how well it fits into the context in which they are using it, and how well it contributes to the quality of their lives.5

UX also encompasses all aspects of customers’ interactions with the company and its services, and wider consideration of the nature of their daily lives and how the company can help to improve them. UX takes design out of the studio and away from the screen and into our lives. This takes us into the realm of experience architecture, providing a powerful set of tools for helping us to craft richer experiences that not only serve needs but anticipate them and that not only please but delight.

Experience architecture is a broad art form. You’re designing for everything from vision and mission to products and performance to moments of truth and the technology and UIs in between. This is why it requires so much more than technical expertise and our own perspectives on what customers want.

In an interview with Wired,6 Steve Jobs spoke about the importance of a breadth of experiences and why great artists approach design through experience architecture:

[T]hey were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things. And the reason they [designers] were able to do that was that they’ve had more experiences or they have thought more about their experiences than other people.

With each word, Jobs reminded us that our own experiences can complement but not always dictate meaningful and shareable experiences for those around us. We need inspiration and empathy:

Unfortunately . . . a lot of people in our industry haven’t had very diverse experiences. So they don’t have enough dots to connect, and they end up with very linear solutions without a broad perspective on the problem. The broader one’s understanding of the human experience, the better design we will have.

EXPERIENCE ANTHROPOLOGY

One way UX allows us to better understand how to do this is by the incorporation of some lessons from the human observational science of anthropology.

Some of the biggest companies in the world are hiring anthropologists for this reason. Google, for example, hired an ethnographer to study mobile behavior. Intel has an in-house cultural anthropologist, and Microsoft is reportedly the second-largest employer of anthropologists in the world.7 As Christian Madsbjerg, a partner at ReD Associates,8 said in an interview on Fox Business,9 “The holy grail of business . . . is to understand why [customers] do what they do and why they buy your product. Human science is about understanding people’s worlds.” Most of the ReD’s employees are experts in psychology, philosophy, sociology, and anthropology, trained to bring astute and nuanced insights about customer behaviors and ways of thinking and feeling into the experience design process.

In his interview with Fox Business, Christian Madsbjerg told the story of how Samsung made use of observations of people’s use of devices in their homes to craft the design of their TVs:

Samsung has a very good take on what’s important to somebody who buys a TV or a mobile phone. What are the things that they look for? Instead of asking people directly, which kind of TV do they want? They go into people’s homes and look at what’s a TV, what’s a TV experience, and what’s a good experience for them? What they found was that even though the men in most families think that they buy the TVs, women actually decide. When women decide on TVs, they look for furniture, not electronics. That’s why the TVs look the way they look and why they sell them the way they sell them.

Imagine really knowing what moves your customers, why they do or feel certain things, and what inspires them. By carefully observing them in their daily lives, you can.

THE POWER OF OBSERVATION

In their book, Everything Connects: How to Transform and Lead in the Age of Creativity, Innovation and Sustainability, Faisal Hoque and Drake Baer tell us of the power of observation.10 I believe that observation is at the core of almost every design philosophy and is core to effective UX and experience design ultimately. The power of observation delivers more than information or insight. Observation leads to inspiration, which then sparks creativity, and innovation follows.

To tell their story, the authors refer to the keen observational curiosity of one of the greatest artists and innovators of all time, Leonardo da Vinci:

Beginning as a painter before he became a sculptor, an engineer, an anatomist, and a painter again, da Vinci was long trained in experiencing and appreciating the natural world—thus the power of his representations. His core skill and greatest passion was observation. . . .

This enthusiasm informed all his work: if you were to peer into his notebooks, you would find sketches of the movement of water, evidencing his lifelong preoccupation with hydraulics, drawings that became foundational studies of the workings of the human body, as well as portraits of the faces of the ugly and beautiful people he encountered in Florence, Rome, and Milan. Many people look, he said, but few people see—and that mindful seeing is the foundation of direct experience, itself the foundation of direct knowledge.

This same acuity of observation can lead to transformative realizations. You have to ask questions. You have to see what no one else sees.

LEGO PUTS THE MISSING PIECES TOGETHER

Observation of customer behavior was the key to LEGO, everyone’s favorite imagination builder, turning around a dramatic drop-off in sales. Just a decade ago, the company was facing a life-threatening downward spiral. In 2000, LEGO was the fifth-largest toymaker in the world. In January 2004, it announced a huge deficit bleeding cash to the amount of $1 million every day. At the time, owner and CEO Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen, grandson of founder Ole Kirk Christiansen, explored a range of strategies to turn the company around. He decided the only option was to step down and turn things over to Jørgen Vig Knudstorp, a former McKinsey consultant, as the new CEO of the company.

Further research revealed that at the heart of the matter was that the company had lost touch with its customers, and a team of researchers were tasked with learning what had gone wrong. According to The Moment of Clarity by Madsbjerg and Rasmussen,11 they immersed themselves in data on how kids play with LEGOs.

“We were constantly asking, ‘What is that kid doing over there? Is that the same as what this kid is doing here?’” After an intense period of discussion about the data, each researcher stepped away and made his or her own decision about the most important patterns.

The researchers brought a whole lifetime of critical training to the pattern recognition process, but they also brought themselves. They melded art with science by using their own perspectives to discern the experiences of the children.

Co-founders of ReD Mikkel B. Rasmussen and Christian Madsbjerg sum up the lessons of the LEGO story this way:

The company’s downward spiral was propelled by its determination to leverage the brand and move into new markets rather than to understand what its customers—young builders and their parents—really wanted from play with its products. . . .

Acting on mistaken assumptions, LEGO branched into action figures and videogames, believing that because kids were increasingly scheduled and often distracted by faster-paced electronic games, they no longer had the time or patience for its old-fashioned plastic bricks. So LEGO products got a lot cooler and more aggressive looking, but they also required less time and creativity from the kids playing with them. Meanwhile, parents’ nostalgia for the old LEGOs began to dissipate, and with it their impulse to buy the bricks.

Observations of people going about their daily lives should ideally be combined with data gathering of various kinds, including data mining, or what I prefer to call digital anthropology. In LEGO’s case, the team had created photo diaries of kids playing in their homes, and these proved instrumental in understanding the core appeal of the classic bricks. It turns out that children needed to rebel against overbearing parents (imagine that!):

During a session with the photo diaries . . . the researchers noted that the children’s bedrooms . . . tended to be meticulously designed by the mothers. One child’s bedroom in Los Angeles was suspiciously tidy with a stylish airplane mobile hanging down. “That looks staged,” an anthropologist observed, and the team discussed what that might mean. The researchers noted that the moms were also “staging” their children’s development.

ReD’s Rasmussen and Madsbjerg explain the LEGO team’s aha! moment:

Key insights began to emerge as the LEGO team methodically sifted through the data. Among them was that children play to escape their overly orchestrated lives and to hone a skill. This insight exposed the false assumption that kids were too busy to engage with LEGOs. In fact, it emerged, a subset of children have both the time and the desire to commit to the bricks and want to achieve mastery.

The research allowed us to make a decision about whom we wanted to reach. It was a decision that grew into a mantra: “We’re going to start making LEGOs for people who like LEGOs for what Legos are.”

This was a game-changing insight that conventional strategy processes—market data analytics, conjoint analysis, surveys, focus groups, and so on—had missed and probably could never have provided.

THE DISSOLVING DISTINCTION BETWEEN DIGITAL AND PHYSICAL

UX is not only about digital experience design, but also about designing the tangible experiences customers are offered in the physical world. For example, Starbucks encourages customers to personalize the drinks on its menu as a way of giving them a sense of ownership over the experience. Doing so creates a bond that’s hard to discount. The same is true with California-based In-N-Out Burger. By offering a secret menu with hidden references, the cheeseburger mecca has for more than 50 years sustained a cult-like relationship between brand and customers and customers and people who have not yet been baptized to the church of In-N-Out.

pashabo/Shutterstock.com

Quality experience now involves a good balance between the abstract and physical, the intangible and tangible.

I love the story told by Tyler Wells in UXMagazine to stress that UX is about the experience, not the product itself. Wells is co-founder of Los Angeles–based Handsome Coffee Roasters, now part of Oakland and San Francisco–based Blue Bottle Coffee. He wrote:

When I was 12, my dad taught me to drive in a 1979 VW Rabbit Diesel with a 4-speed manual transmission. We were on a dirt road in West Virginia. He told me what was actually important about driving: “Drive for your passenger’s comfort.”12

His point is that it’s not about the car, the luxury of the interior, or the quality of the sound system. It’s not about the technology or lack thereof. It’s about the people.

The design of good experiences requires the input of UX into the design of products, services, customer engagement, and also how customers interact with a company or representative online and in the real world. UX experts play the role not only of surveyors of your experience ecosystem landscape, but the construction site chiefs, helping to assure that the ecosystem is built to the right standard. In order to play this role effectively, your UX chief or team must have the clout to bring the wider team in line.

THE ELEMENTS OF USER EXPERIENCE WITH JJG

I was lucky enough a few years ago to sit down with Jesse James Garrett (JJG) for my television series (R)evolution13 to talk about the need to bring UX thinking into the C-Suite. In 2001, JJG founded Adaptive Path, now part of Capital One, to help companies solve user experience problems and advance the field of UX.14 He’s also the author of a significant book I read and reread as I began this project, The Elements of User Experience. 15 He’s a widely respected thought leader in UX design and someone whose work I highly regard.

He shared during our discussion that at a minimum, “Human psychology and behavior must be built into our products.” He continued that over time, UX evolved from a tactical role, which he suggests might share more in common with user interface design, into something where UX is deeply integrated into product strategies.

EXPERIENCES AS ENGAGEMENT

When you review existing customer experiences and begin experience design, I’d like you to think about these words of JJG, about the need to “design for engagement”16:

To use something is to engage with it. And engagement is what it’s all about. Our work exists to be engaged with. In some sense, if no one engages with our work, it doesn’t exist.

Designing with human experience as an explicit outcome and human engagement as an explicit goal is different from the kinds of design that have gone before. It can be practiced in any medium, and across media.

Engagement as a single transaction is simply competing and trying to win in the moment. Engagement as a series of connected experiences, which span across media and context, is what experience architecture is all about.

In 2009, JJG delivered an impassioned speech at the 10th annual IA Summit, 17 an important industry conference for information architects, content publishers, and all who design information spaces.18 During the delivery of his “Memphis Plenary,” he asked members of the audience to raise their hands if they’re responsible for creating digital experiences. A majority of course did so. But then, JJG asked who’s involved in creating non-digital experiences. Not so many hands went into the air this time.

He wanted the UX industry—designers specifically—to think beyond websites and common digital touch-points. So must we. For me, this was and is a call for a rise of experience architects to build a connected world that seamlessly joins analog and digital. This is one of the core achievements that UX experts can help to bring about.

THE CRUMBLING DIFFERENCES BETWEEN BX, UX, AND CX

One question that should come up more than it does is, “What is the relationship between BX, UX, and CX?” The sad truth is that today, at most companies, there isn’t much, if any, relationship between them. It’s rare for specialists in these several disciplines to interact, and even less common for companies to integrate them in experience design efforts. This is a travesty, as they have much to share with one another. At this point in the book, you have to be the source for clarity and direction.

BX: BRAND EXPERIENCE

We haven’t had too much discussion about brand up to this point. A brand should be guided by a North Star, not a logo or a tagline. A brand should also communicate a vision and a purpose. It must be backed up by a brand architecture to serve as the standard for more than creative; it becomes the framework for experiences.

Specifically, a brand experience is a brand’s action or state perceived by a person. It’s felt. Every interaction between an individual and a tangible or intangible brand artifact contributes to the brand experience as a whole.19

CX: CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE

While the customer experience is often characterized as the perception a customer has after engaging with a company, brand, product, or service, as Beyond Philosophy, a consultancy focused on customer experience, points out, much of the customer’s experience is also subconscious:

A customer experience is not just about a rational experience (e.g., how quickly a phone is answered, what hours you’re open, delivery time scales, etc.).

More than 50 percent of a customer experience is subconscious, or how a customer feels.

A customer experience is not just about the what, but also about the how.

A customer experience is about how a customer consciously and subconsciously sees his or her experience.20

McKinsey partners Alex Rawson, Ewan Duncan, and Conor Jones observed in the Harvard Business Review that the focus of CX experts so much on what customers say in satisfaction surveys and in the actual interactions with companies has blinded them somewhat to the wider and deeper customer experience:

Companies have long emphasized touch-points—the many critical moments when customers interact with the organization and its offerings on their way to purchase and after. But the narrow focus on maximizing satisfaction at those moments can create a distorted picture, suggesting that customers are happier with the company than they actually are. It also diverts attention from the bigger—and more important—picture: the customer’s end-to-end journey.21

As we’ve spent the last chapters discussing UX, it’s hopefully clear that it is essential in enhancing the perspectives of CX and experiences holistically. If CX is to have genuine relevance at a human level, it must encompass a human-centered design approach. And it must mean something in everything and in every step and in every way, including mind, body, and soul.

Business meets design when:

1 www.nngroup.com/articles/denition-user-experience/.

2 www.amazon.com/Design-Everyday-Things-Donald-Norman/dp/1452654123.

3 www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-101-introduction-to-usability/.

4 www.techterms.com/denition/user_interface.

5 L. Alben, “Quality of Experience: Dening the Criteria for Effective Interaction Design,” Interactions 3, no. 3 (1996): 11–15.

6 http://archive.wired.com/wired/archive/4.02/jobs_pr.html.

7 www.businessinsider.com/heres-why-companies-aredesperateto-hireanthropologists-2014-3.

9 vimeo.com/89719698.

10 www.fastcompany.com/3024779/dialed/how-curiosity-cultivates-creativity.

11 Christian Madsbjerg and Mikkel Rasmussen, The Moment of Clarity: Using The Human Sciences to Solve Your Toughest Business Problems (Boston: Harvard Review Press, 2014).

12 http://uxmag.com/articles/ve-customer-experience-lessons-coffee-taught-me.

13 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QoYzFyp3Ezk.

19 www.brandexperience.info/denitions/.

20 www.beyondphilosophy.com/customer-experience/.

21 hbr.org/2013/09/the-truth-about-customer-experience/.

4.3

HUMAN ALGORITHM

THE HUMAN SIDE OF INFORMATION

At the point where X marks the spot, you’ll see that it stands at the intersection of people, technology, and humanities (the arts). As such, when it comes to customer experiences, there is no B2B or B2C or B2B2C; it’s all about P2P—people to people, what brought them to this moment, and what/how they’re moving forward.1 So getting to know the people who are your customers, not as numbers but as well-rounded, flesh-and-blood individuals, is the baseline.

The first step is appreciating that you and many of your customers are not much alike. You’re quite similar, I’m sure, to some of your customers, but most of them have different life experiences and perspectives, and different tastes and hopes and dreams than you do.

You’re probably already using data to some extent to inform you and your team about who your customers are and what they want. Big data provides great information about customers’ interests, personal and professional networks, location, and many other characteristics. But creating meaningful experiences requires us to get more personal than just mining data. One of my least favorite expressions is, “It’s not personal; it’s only business.”

Data is vital in effective experience architecture, but it’s not sufficient. You also need interpretation that offers deeper insights about customers’ lives, and about what you can offer to improve them. That kind of insight is what has allowed Apple to be so successful. If customer enchantment is about people, then equally it takes people, not politics or legacy processes, on the inside to bring about change.

Gathering data is the easy part. The challenge is connecting the data gathered to strategies for qualitatively changing the experiences being offered. This takes not only looking outward at your customers but also inward at your team.

Let’s take post-transactions as an example. Loyalty and POS (point-of-sale) data don’t necessarily have clear ownership, either, and channel leaders are kept in the dark about cross-departmental loyalty efforts. While everyday customers see only one brand—even if loyalty touch-points are not connected or working together internally—channel leaders are not kept abreast of what other departments are doing in terms of maintaining loyalty, and therefore aren’t aware of how it integrates into current infrastructure. As a result, multiple teams own important loyalty and point-of-service data, which makes it difficult—if not impossible—to locate and access that data.

FROM UX TO DX (DATA EXPERIENCE)

Data presents the ability to convert unknowns into knowns and assumptions into truths. In addition to UX expertise you need a data artist working with your team. These brilliant data analyzers can surface many revelatory insights that you’ve been missing in your customer data.

A true data artist performs sophisticated listening and applies analysis algorithms to transform mere data into stories about your customers’ experiences with you and in their wider lives, as well as about their hopes and dreams. The combination of the human science of observation and the insights of data artistry provides the fully robust understanding of your customers, their behavior, and the opportunities you have to improve their experiences, which should be your goal.

In his paper, “From Data Scientist to Data Artist,”2 author and consultant Jim Sterne defined the role this way, making a distinction between the basic job of a data gathering and analysis and this more qualitative insight generation:

A data scientist is responsible for understanding and advancing the nature of data, its collection methods, and the algorithms for processing it. . . . A data artist is responsible for delivering fresh insights from data to help an organization meet its goals. This is the person who takes the output from decision-support systems and turns it into consumable theories, postulates, and hypotheses that can be tested and applied to the business.

We have an almost overwhelming volume of data to work with these days, and that means that most companies are missing many important clues that could help transform their offerings. Those who are experts in divining the treasure to be had will not only make sure that you’re gathering all of the right data in the first place, but that it is probed into with the appropriate closeness of attention and experience in surfacing aha! realizations of the kind that LEGO came to about why kids love their classic bricks.

In addition to making sure you are tracking all the right data signals such as conversations with customer service and customer sentiment, data artists will produce a richer understanding of your customers’ preferences, the trends in their behavior and desires, areas for innovation or refinement of your products and services, areas in which R&D should be focused, and opportunities for co-creation with your customers and for relationship building.

You want to be unearthing insights into the following characteristics, habits, and values of your customers:

Persona—who I am and who I aspire to become

Expression—what I say

Publication—what I share

Profession—where I work

Opinion—what I think or believe

Details—how and where to join me

Reputation—what others say about me

Hobbies—what I’m passionate about

Certificates—who can certify my identity

Purchase—what I buy and/or intended to buy

Knowledge—what I know

Avatars—what represents me

Audience—whom I know

Interests—whom I connect to and what interests bind us together

Values—what I align with and stand beside and what’s important to me

Location—where I go

Trends—what my peers and I are investing in on the horizon

Experiences—what I experienced and what I shared with peers

CAPTURE THEIR INTENTS, NOT JUST THEIR COMPLAINTS

One great example of the creativity that a true data artist can bring to the enterprise of gathering and analyzing data is the concept of vendor relationship management (VRM), developed by Doc Searls, co-author of the highly influential The Cluetrain Manifesto, author of The Intention Economy, and fellow at the Center for Information Technology & Society (CITS) at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Searls has criticized the nature of the general practice of customer relationship management (CRM), arguing that most often it’s not truly focused on the relationship. Most companies focus too much on only one side of the engagement equation: how to market, sell, and serve. On the other side is how customers demand to engage and be engaged.

In a presentation at a national gathering of Internet Advertising Bureau members in 2013,4 Searls held nothing back regarding his views, saying: “Customer Relationship Management [today] is about [marketing and] sales and not about the relationship. It’s about deflecting customers and minimizing contact.” We encounter CRM not through personalized, continuous engagements throughout the lifecycle, he continued, but through call centers, junk mail, and “come-ons of various kinds.”

What if relationships actually mattered? Enter Searls’s idea of vendor relationship management. VRM encourages the development of engagement tools and services that make it easier for customers to engage with companies on their terms, in their preferred ways, which also allows companies to gather higher quality data about their desires and the experiences they’re having with the company.

At the heart of VRM is what Searls refers to as intent casting (#IntentCasting). Searls explained the concept in an interview with Tom Silver published in Harvard Political Review:5 “For example, if I want a stroller for twins from Boston Commons, and I’m willing to spend $200, I can advertise that fact and businesses can come to me.”

Intent casting is a sort of personal request for proposal (RFP) or request for quote. Searls shares the example of Airbus seeking new engines for a new project. The company might issue an RFP to Rolls Royce, Pratt & Whitney, and GE, just to name a few.6 Searls says that it’s only a matter of time before customers begin doing the same. Actually, they already are. And here is where data artistry comes in.

Most businesses just don’t have the infrastructure to notice or capitalize on these expressed intents and interests. So Searls is advising companies to create systems that connect posted intents and interests, allowing them to engage. This is the kind of qualitative improvement in your data systems that a data artist can help you make.

Now look ahead to the diorama of possibilities for more powerful data gathering and analysis as the Internet of Things develops, in which products will increasingly communicate directly with one another and through other devices to other products, machines, or customers. The cloud provides a domain where the voluminous information this will generate can dwell. But it can’t by itself produce valuable insights from that data. You’ve got to be sure you are optimizing your data gathering and analysis to do so.

Remember, data is just the beginning. Data must always tell a story. And that story must be about people. Good stories always are. This is where your UX expertise combines with data artistry to breathe life into your understanding of your customers. The beginning of bringing them together is the customer journey mapping process, so we’ll now turn to the specifics about creating great journey maps.

1 www.briansolis.com/2008/02/social-media-is-not-nal-frontier-of/.

2 http://anametrix.com/from-data-scientist-to-data-artist.

3 Photo: Alessio Jacona

4 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x5bHIL_kK8w.

5 www.iop.harvard.edu/digital-economy.

6 http://vint.sogeti.com/expert-talk-doc-searls-on-the-intention-economy-and-vrm/.