2. Getting the Product to Market: Who and How

In an industry that depends not only on getting to market before a trend has passed—and in some cases, even creating the trend in the first place—what does it take to create big box office, platinum records, bestsellers, and all the associated revenue streams attached to that original content?

The usual marketing questions are all present: where to market the product and to whom; how to price, package, and position; when to introduce the product; how to communicate the product’s values, benefits, and availability.

But as discussed earlier, in entertainment the cycle is condensed. Entertainment products are of the moment. They are not investments, like cars or furniture. They are not consumables, like detergent or toothpaste. They are seasonal only from the perspective of blockbusters for the summer or family movie for the holidays. The content is ever-changing and, when successful, ever-growing.

This chapter examines what it takes to bring an entertainment product to market in today’s world and the people and players who drive this enormous business.

Molding the Message

If entertainment itself can be broken into four Cs, the entertainment hierarchy can be defined by three Ps: people, power, and players.

Although many of the broad issues in the entertainment industry are the same as they might be in almost any business, the speed at which a product must be delivered, coupled with the budgets associated with the product, demand that hundreds of dots be connected in a very short time span. That level of play requires the power to make things happen, and people willing to do what it takes to make them happen in time.

With no creative production lines and no linear progression from start to finish, marketing must ride the development process, supporting all the products associated with the core content: soundtracks, electronic games, theatrical scripts, licensed merchandise—any intellectual property that will put the original product into the black. The marketing message must maintain crystal-clear consistency to reach these goals. Even the aspiring actor sweating under the Orlando sun inside a theme park character costume must deliver an experience that is harmonious with the consumer’s expectation.

Entertainment starts as a momentary fancy in the public’s imagination; the role of marketing is to carefully feed and water that fancy until it grows into something much larger, more extendable, and more profitable.

In most industries, marketing decisions are based on deep and thorough research, tied into short- and long-term planning objectives. Strategic planners have reams of data on what the other guys are doing, how the market is responding, what price points have been covered, market saturation, and how this year’s new product introduction will open the door for something slightly more radical next year.

Although research plays a part in entertainment development, the entertainment marketing executive must understand the public’s tastes and be able to guess where those tastes may be heading—often in the face of research or precedents that might say otherwise. After all, data doesn’t become data until after a trend begins. Entertainment must exploit new veins while mining old ones.

The executive must know in his or her gut when to give the green light, that final nod of approval—knowing full well that his or her head may roll if that gut feeling is wrong. The associated marketing campaign must absolutely recognize all the factors, all the trends, and all the tastes to best position and promote the product while the product is still in the content phase. A wrong decision can destroy a major asset and the millions or billions of dollars in goodwill developed over decades.

Even as the core content is undergoing this gut-wrenching ride, the associated products—that which will feed the revenue streams—must undergo the very same rollercoaster. Missing the opportunity at the wrong time of the year—say, Christmas—can leave a gaping hole in the company’s balance sheet.

Finally, the marketing of entertainment demands an approach that is entertaining in and of itself. Entertainment and marketing have become so incredibly intertwined that it is almost impossible to separate one from the other. Consider this: What is a T-shirt with the name of the latest hot band printed across the front? Is it a promotional item, or an extension of a revenue stream?

In the Good Old Days...

Regardless of the industry, product, or service, marketing is about brand development, customers, and matching one to another while motivating the prospects to make a purchase decision. This has been the province of traditional companies—the Coca-Colas, Fords, and Apples—throughout the twentieth century.

During most of this time—certainly up until the 1970s—entertainment remained a cottage industry developed by entrepreneurs and wheeler-dealers who had little use for marketing, other than an add-on when a film was ready for release. They spent money only on product production and the sales representatives they needed to close the deal and gain distribution. Entertainment and media had several things in common, but most importantly, they were all experiential businesses, simply giving the customers a good time or a break from their everyday problems.

This was relatively easy because the competition for discretionary time and disposable income was fairly uncomplicated. A simple announcement or awareness campaign would sell out movie tickets, sports events, rock concerts, Broadway shows, and most other entertainment options. The three television networks made channel switching a minor issue, and counter-programming was but a twinkle in the strategist’s eye.

But in the middle of the twentieth century, the entertainment and media world took on a new look, with major corporations or investment groups buying up well-known studio brands that had struggled and were experiencing hard times. Some were bought for the glamour of the name. Some were bought for the real estate the studio was built on. The film libraries of these studios were of lesser concern—after all, the only way to remonetize those movies was to ship them off to the Million Dollar Movie, shown at 10:30 p.m. in metro marketplaces. There were no VCRs, DVDs, tablets, smartphones, or cable networks.

Yet.

By the early 1980s, a huge shift had begun to take place. Major brands gave the entertainment industry access to a world market. Competition between products and leisure services began to intensify as the consumer’s available time became more compressed. A cultural revolution was opening the pocketbooks of women and teens. The need to refine the marketing strategy within the various entertainment niches became more apparent as more products competed for the same dollars.

Vive La Revolution!

Entertainment executives, eager to hold on to and increase their market share, overcame their earlier reluctance to expend time and resources on marketing. The pendulum now swung to enormous advertising and promotion budgets to attract and motivate consumer purchases.

Today, studios with 12 to 15 films releasing in one year mount a marketing war chest of $500 to $750 million. They work with leading global advertising agencies or media buying services, supported by in-company creative units and directed by experienced marketing professionals.

Television networks have also thrown their hats into the marketing fray. Having for years relied on free or unused airtime on their own networks to promote new programs, research showed that this form of promotion simply spoke to the same committed network viewers. Marketing plans for networks began to include the previously unmentionable or impossible idea of using print advertising in newspapers, magazines, TV guides, or even TV listing pages in local tabloids. They then expanded to using cable, outdoor billboards, and the ubiquitous subway and bus posters, where millions of urban workers spend their transport time to and from work.

Magazines, already in partnership with advertising agencies and advertisers, took some of their own marketing advice and developed dual-strategy marketing campaigns: one for the consumer to build awareness of upcoming magazine issues and the other directed at the business community to announce growing circulations. This enhanced the quality of their reader demographics in terms of age, family size, income, and even spending habits. Marketing campaigns based on special promotions encouraged readership trials.

Even cable TV, long a free-rider on network TV’s coattails, came to the conclusion that effective marketing was necessary to brand new channels, build awareness, and stand out from a universe of exploding channel growth—hundreds of choices and still counting.

Radio, sports venues, electronic games, theme parks, blockbuster books, and unique imprints all rapidly joined this entertainment marketing revolution. Budgets expanded and new, sometimes outrageous themes and tactics were implemented to stand out in this fast-paced, perishable world of glamour, glitz, and blockbuster entertainment.

As all of this rolled along, the companies themselves became blockbusters, sprawling concerns stuffed with synergistic opportunities. The idea of using other media to market one’s core concept grew into owning that other media, using it in the ever-widening battle for the consumer.

Super-Size Me

Today, in the place of the old-time studios, we have mega-entertainment and media companies built and nourished to capture every possible penny connected with their intellectual property. With this new beast came a breakthrough in marketing, a strategy known as integrated communications, which calls for all the various tactics in the brand or company’s portfolio to work together under one umbrella strategy.

Originally, this approach meant that classic advertising—television, cable, radio, outdoor, direct marketing, sales promotion, public relations, yellow pages, skywriting—all worked in tandem and stayed on point toward the ultimate brand message. This was employed as the marketing machinery turned on behind studio films, major television shows, the launch of new electronic games and consoles such as PlayStations 1,2,3, Xbox, and Wii. The marketing of the brand or content continued throughout each of the windows: home video, premium cable, network TV, streaming video, Internet portals—and international repeats of these domestic windows. A whole marketing universe opened, extending the life of the otherwise perishable product for years.

Then came another breakthrough. The brand handlers (managers and chief marketing officers) found that content sectors such as animation, action adventure, and certain dramatic series could go beyond the windows of basic distribution and consumer consumption. These onscreen (large and small) brands could morph into games, books, toys, clothing, theme park rides, ice shows, Broadway events, and myriad products frequently manufactured offshore, creating tsunami of gain and profit. The revenue from these products was and is difficult to collect as data, but the revenue has a huge impact on the bottom lines of the media conglomerates and their suppliers.

The outcome of this strategy might be known as compounded marketing, given that it has the same effect as compounded interest, forever growing against the principal—in this case, the original content.

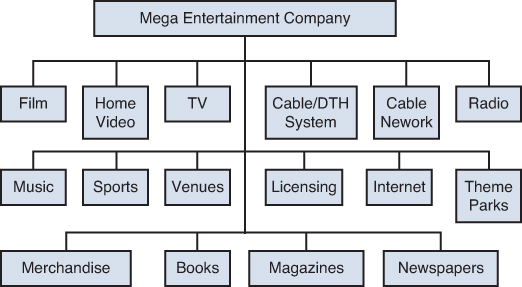

Today’s mega-company looks something like what you see in Exhibit 2-1.

How does this come to be? Let’s use Viacom as an example.

First, start with a chain of movie theaters for stability, then add a movie studio, a book publishing company, a cable operator (with several major cable programmers), and a leading video retailer. Next, sell off the cable franchises, add a retail store, close the retail store, acquire a national radio network. Add a billboard company and get a television network in the bargain. Sell off the textbook division of the publisher, trigger the option on acquiring the majority share of another television network, and then grab a wrestling franchise and incorporate it under the programming umbrella. Then go after a major studio in a world-class hostile takeover and add another publisher as part of the deal.

Viacom became a mega-entertainment company, owning Paramount Studios, CBS, MTV, Nickelodeon, and BET, among a raft of other acquisitions. This was big news back in 2002 when we published The Entertainment Marketing Revolution. But in true mega-entertainment company style, the show wasn’t over yet.

In 2005, Viacom, interested in giving some oomph to a stagnating stock price, announced that it would spin off parts of the company. CBS Corporation would now own the CBS television network, CBS Radio, Showtime, CBS Outdoor, CBS Distribution, and Simon and Schuster. The new version of Viacom would own MTV, BET, Nickelodeon, and Paramount. Two rival executives, Les Moonves and Tom Freston, were put in charge of the two new companies, Moonves with CBS Corporation and Freston with Viacom.

It was thought that CBS would be the “slow growth” wallflower of the two, with the assumption being that cable would grab ratings share. But through retransmission, licensing, and great programming moves—with such hit series as Survivor and all the various CSI franchises—CBS and Moonves became the wunderkinds.

The other piece—the new Viacom—lost its way. Freston didn’t do well in this spinoff. Only eight months into his tenure, he failed to purchase MySpace, which was snatched up by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation for $580 million, instead of the $500 million Viacom might have taken it for earlier. Freston’s head rolled. Changes at the executive suite left management to newbies. The new management team did not aggressively continue their marketing posture and lacked clarity on their audience segments, muddying the message and losing viewers, while their competition—Cartoon Network and the Disney Channel mainly—came charging up from behind.

MySpace? Sold by News Corp. in 2012 for $35 million. Mr. Freston might have gotten one last laugh.

The Viacom story is an excellent example of the importance of keeping brand identity and brand equity. Marketing is about presenting the clearest communication of the corporate mission, along with the products, name, logo, and various divisions.

Probably the best example of an entertainment marketing powerhouse with a clear brand strategy is The Walt Disney Company. This company preaches synergy day and night, strategizing marketing and its halo effect, enabling one form of a product to morph into another. Think of their original products—The Lion King and Beauty or the Beast, for example—which have translated into hundreds of thousands of spin-off retail items. Both were turned into Broadway musicals, launching a whole new division of the company. Disney is able to stretch those brands into as many different successful products as consumers will accept and purchase.

Disney’s success is not limited to feature films and animation. For example, Disney took a very successful cable channel, ESPN, and multiplexed that brand into ESPN2 as a platform for extreme sports and college games. Then it launched ESPN magazine, which is now considered a legitimate competitor to Sports Illustrated. Today’s ESPN owns the rights to televise Major League Baseball, NFL, NBA, NASCAR, tennis, a host of college conferences, the Bowl Championship Series, and the new playoffs the BCS has just announced. ESPN and ESPN2 have 98.5 million subscribers and bring in more than $6 billion annually from subscriber fees alone.1

1 “Fox to Create New Network It Sees as Rival for ESPN,” New York Times, March 5, 2013.

In 1995, Disney launched its cruise line business with the decision to build two purpose-built ships, designed specifically to accommodate both families and adult cruisers with no children. Although many wondered if Disney could pull this off—especially considering there would be no gambling, a cruise-line staple—the company has performed spectacularly. There are now four ships in the line, cruising around the world. It is estimated that Disney Cruise Line owns nearly 3% of the world cruising market.2

2 “2013 World Wide Market Share,” Cruise Market Watch, 2013-4-29.

The Mouse also has a house in the interactive world, courtesy of Disney Interactive Media Group, which includes Disney Interactive Studios (offering games based on Disney franchises and new properties across multiple video game platforms); Disney Online Studios (immersive, online virtual worlds such as Disney Club Penguin and the World of Cars Online); Disney Mobile (mobile entertainment content, including music-based games, casual games, franchise apps, digicomics, and informational apps); Disney Online (access to Disney movies, television, games, music, travel, shopping and live events); and Playdom, which produces casual games for social networks such as Facebook and Mr. Freston’s old nemesis, MySpace.

Within every branch of these mega-companies there are contingency budgets, teaser campaign budgets, tie-in product budgets, and (in the case of movies) budgets to encourage home video rentals and sales as well as pay-per-view cable viewing. The game of out-spending and out-marketing at the highest dollar level is played only by the leading studios, eager to take advantage of the various consumer viewing windows available to them in the entertainment universe.

But not everyone in the entertainment world is a major player with huge resources; companies with small or non-existent budgets are becoming more mainstream. Every aspect of the industry—faced with politics, budget cuts, forced retirements, and fallout from the vast quantity of consolidations—finds hundreds of talented youngsters and experienced professionals creating production companies and support businesses. These include advertising boutiques, public relations enterprises, media buying shops, and other opportunities built around the business.

From blockbuster extravaganzas to off-off-off-Broadway plays, the marketing team is an intrinsic part of the success, creating strategies that will develop awareness for the product and extend the brand as far as it can possibly stretch. On the awareness side, it could be major stars meeting the press at a five-star hotel or stenciled messages on a New York sidewalk. On the revenue side, it’s licensing the brand in as many ways as possible.

Whatever it takes, entertainment marketers must focus the public’s attention on their product above all others. Their ability to do so—and the revenue that results from their efforts—has led to a revolution in entertainment marketing.

Decisions, Decisions

Marketing professionals face a variety of decisions on each project, in no way limited to how much or where to spend, which define the nature of the message. How those decisions are made differs across the board. Some professionals pride themselves on seat-of-the-pants, nose-to-the-breeze, arbitrary guesswork, while others swear by the application of sophisticated analysis, feeding off the ever-growing mountain of information now known as Big Data. In any case, there is very little margin for error.

And yet error and the unpredictability can reign. With movies, slippage plagues the release of each film. No matter how careful the planning, there may always be the surprise that makes winners out of weak entries and losers out of sure things. As mentioned previously, social networking—that bonanza of buzz—can be a blessing or a curse.

Surprises may come from other corners of the marketing universe, especially with the constant stream of related decisions being made in other areas, decisions that are difficult to categorize or visualize until they are fully discussed, formulated, argued over, and weighed against the possible political repercussions. This keeps everyone on their toes, trying to predict the unusual or unpredictable—or at least being flexible enough to shift positioning if the circumstances require it. In the tightly wound world of entertainment, “positioning” could refer to the positioning of the product or the personal position of a team member savvy to the politics of the industry.

In any case, decisions can be broken down into three categories:

![]() Large decisions

Large decisions

![]() Small decisions

Small decisions

![]() No decision at all

No decision at all

Small Decisions

Small decisions include those that are recurring, consistent, must be made week after week, month after month, season after season, and usually look similar from studio to studio—or even from sector to sector. These decisions, formulated by the marketing team and signed off on by the executive in charge, include

![]() What is the marketing budget?

What is the marketing budget?

![]() When will we launch it in the marketplace?

When will we launch it in the marketplace?

![]() Who is the hypothetical target audience?

Who is the hypothetical target audience?

![]() Will we spend the advertising budget in network, Internet, mobile, cable, and print or use some other media mix?

Will we spend the advertising budget in network, Internet, mobile, cable, and print or use some other media mix?

![]() What is our fallback plan, and how fast can we employ it?

What is our fallback plan, and how fast can we employ it?

![]() What are the key elements for the visual aspect of the campaign?

What are the key elements for the visual aspect of the campaign?

![]() Which service organizations will be used for research and advertising?

Which service organizations will be used for research and advertising?

![]() Is there a seasonal message as part of the marketing push?

Is there a seasonal message as part of the marketing push?

There are hundreds of these small decisions that must be made, some with a planning timetable of 6 to 12 months and some that must be made with the snap of the fingers to respond to the particular situation in the marketplace at the moment.

Large Decisions

Large decisions, usually made by the leader or chief executive of the company with the brain trust of advisors and board members, include

![]() Should the company acquire a competitor or any allied company?

Should the company acquire a competitor or any allied company?

![]() If there is a merger or acquisition, what will its impact be on the marketplace situation?

If there is a merger or acquisition, what will its impact be on the marketplace situation?

![]() Will a merger or acquisition allow for a dominant share of market in the sector?

Will a merger or acquisition allow for a dominant share of market in the sector?

![]() What will be the expected impact on the competition’s marketing practices?

What will be the expected impact on the competition’s marketing practices?

![]() What will the government accept or reject?

What will the government accept or reject?

![]() Is there potential for expanding global marketing clout?

Is there potential for expanding global marketing clout?

![]() Is this potential ally going to provide access to a new audience segment?

Is this potential ally going to provide access to a new audience segment?

![]() Will it provide marketing efficiencies that create greater returns on advertising and branding investments?

Will it provide marketing efficiencies that create greater returns on advertising and branding investments?

These decisions are generally made over a much longer period of time but may also appear quickly on the radar screen, depending on opportunities in the marketplace. They call for strong leadership and good instincts in the industry as a whole.

No Decision at All

The dreaded no-decision-at-all decision can happen when a process has gotten out of control, costs have skyrocketed, finished product has been delayed, and no one wants to take the blame for a bad call.

In still-entrepreneurial environments, the practice of avoidance and the seeking out of scapegoats for potentially bad decisions or inactivity are signals that the marketing and management processes have broken down, the organization is frozen, and the leadership is failing.

Relying on Research

To avoid the no-decision-at-all scenario, companies rely on research. Though this may sound at odds with the earlier discussion regarding shelf life, it’s important to remember that entertainment doesn’t just follow trends; it creates them. One of the jobs of the entertainment marketing executive is to understand where the zeitgeist might be heading and to license products around that.

Research can uncover new veins in the mother lode of consumer desires. With the dollars at stake, creating any kind of marketing plan without a carefully designed research program is a cardinal sin. This need for research extends to the introduction of a new product, the relaunch of an old product, the extension of a successful product line, or the capture of leadership share for a corporation or division.

But even the most hardened professionals will admit that research can only measure so many variables and give limited but reasonable direction. Industry stories abound of huge research projects, costing hundreds of thousands of dollars, that were ignored by the CEO—who put a finger into the wind and went with his gut.

These stories are usually told only when a project was ultimately successful.

Research now shapes television programs to meet market demand. The AC Nielsen companies provide the most comprehensive network/local television ratings and “share of audience” research systems, through diary panels and some recording boxes. Arbitron gives similar information for local and national radio stations, and Starch helps advertisers understand the influence of powerful ads in the magazine editorial environment. EDI-Neilsen is now one of two or three companies that specializes in the electronic transmission of audience ticket sales over a weekend, providing instant gratification—or the Maalox moment—to tension-stricken executives waiting for the results of a box office hit or bomb. Measurement also exists for music sales, cable audience penetration, and movie box office sales.

And of course, there’s the set-top box: that black blinking thing that links you with your cable provider. That box sends back all sorts of information about who watches what during which time period. So does your smartphone, your tablet, your Roku, your Apple TV—any digital device that brings entertainment to you is capable of taking information from you. Your media actions and preferences are constantly tracked. This wealth of knowledge allows the entertainment marketing ecosystem to plan, target, create, and monetize new content.

The availability of finely tuned research has increased the number of decisions made in any entertainment sector. Product diversification, fragmentation, and a rapidly increasing population have led to a trend away from mass marketing and toward niche marketing. Just as Coca-Cola realized there are diet soda natural fruit-based beverage and just plain water market segments in addition to the classic cola segment, the entertainment industry has realized there are different demographic, age, gender, and other niche target markets for a variety of vastly different film, TV, sports, radio, and publishing genres. This is great for cross-media marketing but certainly creates even more decisions in an already pressure-packed industry.

Tailoring the Team

As mentioned previously, today’s entertainment marketing team has become a key player in the development of the initial entertainment concept itself, molding concepts to fit demographic niches. The marketing team is now a standard fixture at the conceptual stage of product development in all entertainment sectors. The team’s presence at this stage allows for additional time to develop a creative strategy, a marketing plan, a media schedule, and alternatives to each that take into consideration goals achieved, exceeded, or not reached.

There are those who sometimes decry the influence of the marketing team in the development stage, pointing to the reliance on research and data that can change quickly in today’s fast-moving world. And, there are those who feel that content is better left in the hands of its traditional sponsor, the production team. On occasion, if the production team is under pressure to produce results, there is an adversarial atmosphere. In this case, if a movie is successful, it is the brilliance of the production team; if a film fails, it is the fault of the marketing team.

Roles and Jobs

In the best of all worlds, it is usually the excellence of the often hundreds needed to make it all come together. In this integrated environment, the questions of who is on the team, what they do, and how they work together tend to overlap in the process of creating a sustainable product that meets the marketing goals of the company.

The simplest way to explain the complex structure of the entertainment/marketing team is to make a distinction between roles and jobs. For example, the job of a talent agent or business manager may include the responsibility of assembling and packaging a team of talent for the production of a creative product. The agent’s/manager’s role might also embrace the marketplace positioning of the product, through the particular relationships with the team members he or she has helped assemble. Regardless of the task, the agent’s or manager’s goal is to make the product a “must see,” a “must read,” or a “must watch.”

The titles of the marketing professionals reflect the intertwining of marketing and production. They may include the president of licensing and merchandising, head of home video sales, entertainment attorney (who could be in-house or at a firm), chief financial officer, talent agent, literary agent, and president of an independent production company.

Then there are the heads of subsidiaries that could provide synergy and develop supplementary income streams. These would include the head of television production, the head of cable and DBS licensing, the head of theme park ride conception, the heads of the music and publishing divisions, as well as their business development and marketing executives. And let us not forget the head of publicity, an executive who has moved up through the ranks of public relations and owns the fattest contact list in town.

All of these executives will not be found at every meeting. They are kept informed with daily and weekly updates on the progress of production, the market potential, and any audience research that has been done in the field. They are well aware of the usual “windowing” dates (the time gap allowed between the arrival of the film in theaters and the date on which the film should be released in each of the supplementary or ancillary distribution forms—network broadcast, premium cable, DVD, Netflix, and so on). They must know the final, or “drop dead,” dates and which critical decisions must be made for the final and confirmed release dates of the entertainment products in production.

They must be fully aware of the various synergistic products that may have been created to grow the concept. If the marketing plan involves a CD with a soundtrack from the film, or a PBS concert features a major pop or operatic world star about to release a video, then everyone, in all jobs and responsibilities, must collaborate on a consistent message and audience target.

In each sector, the nature and job description of the teams may differ, but there is no doubt that the planning, strategy development, implementation, and measurement of success—or the learning experience of a failure—separate a superior marketing team and secure its place in the corporate environs. However, all of this presumes that business is careening along as usual. When business becomes “unusual”—a star is replaced on a film, the script goes through rewrite number 33, or the lead singer needs surgery on her vocal cords—the dates, the costs, and the marketing plans must be reworked.

In any case, keeping the marketing machine on track means managing myriad details, from concept to consumption. In some cases, major entertainment companies reach outside their own in-house teams for additional support and input. This often involves the use of an advertising agency.

The Role of the Outside Agency

Of the over 2500 advertising agencies listed in the Red Book (a major reference source in the ad business that provides information on clients, geographic concentration, specialties, global coverage, billings, revenue, and senior executives), most do not list an entertainment company as a client—for a variety of reasons. For some, it is lack of experience; for others, it is the challenge of the industry’s volatility; and for others still, the unbundling of services makes the industry unaffordable to service.

The reported spending for this sector of the economy totaled well over $10 billion in measured media for the year 2000. The spending level has increased consistently over the last 10-plus years. As digital movies have reduced the money spent on prints, advertising budgets have ramped up. Over $100 million was spent in advertising on the worldwide launch of Avatar alone. With similar amounts for Harry Potter, Pirates of the Caribbean, Spider Man, and The Avengers, the figure for U.S. spending on advertising for entertainment products, across all platforms, rocketed to nearly $100 billion in 2012.

Agencies that have established a foothold in the industry find great loyalty and very little turnover of the account until there is a perceived client conflict or deep business decline. They also find a feeding frenzy when the mega-million-dollar media budgets and total marketing programs for Disney, Warner Bros., and NBC/Universal go up for periodic review.

Entertainment companies also frequently access other suppliers through advertising agencies, including research firms, consulting firms, data suppliers, direct marketing companies, trailer houses, media planning and buying specialists, public relations firms, Internet agencies, and lobbying firms. Each of these serves a different purpose in the development of an integrated entertainment marketing plan and implementation program.

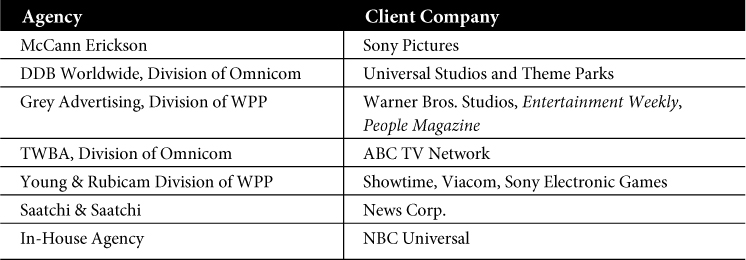

Today’s agency scorecard looks like what’s shown in Exhibit 2-2.

Exhibit 2-2 Major Agencies Representing the Entertainment Industry3

3 As of September 2012.

There are also many small and mid-sized agencies handling diverse creative and media projects for entertainment companies. These agencies are finding new ways to showcase their other clients through their entertainment accounts. The entertainment companies are more than happy to help them out through lucrative sponsorship, licensing, and (in growing numbers) product placement deals.

In the entertainment marketing industry, large budgets and intense time frames call for seasoned teams of marketing professionals who have the right instincts, the ability to make quick decisions, the knowledge of when to rely on research, and great contacts both inside and outside their own companies. Making the right decision on a consistent basis—along with a healthy dose of handshaking, back-scratching, and the right moment at the right time—can propel a professional to the top of the heap, where he or she is recognized as a leader.

Movers and Shakers

Regardless of who he or she has placed on the team, the leader bears the ultimate responsibility for moving the entire process forward to the end result: a transaction for money—in fact, lots of transactions for lots of money. The successful leader accomplishes this task through a very fragile series of relationships and deals: some based on talent, some on money, some on power, and almost all (in entertainment) based on personalities. The people who rise to the top of the entertainment industry understand how to manipulate all of these factors to create a winning outcome.

Follow the Leader

While teams of experts assist with the various steps involved in the marketing timelines, including awards presentations, deal negotiations, and contract completions, they can only help the boss navigate the precarious grounds in the attempt to avoid disaster: cost exceeding revenue, or the other side of the creative-based coin of entertainment, nothing happening at all. Delays can come from a strike by writers, a concession demanded by a star, even a hurricane—either in the form of weather or a disgruntled studio executive.

In an industry based on human talent, the leader must be a consummate politician, a brilliant strategist, and a charismatic executive who can make things happen. He or she must lead, guide, direct, manage, support, compensate, build, and structure the creative process.

In the entertainment world, money is the ultimate report card—a report card that is published not only in industry magazines, but also in consumer periodicals ranging from The New York Times to People magazine. Entertainment leaders, who consistently make great bets for big studios, may make far less money than a film’s superstar (though nothing to sneeze at), but they deal in a different reward: the power that allows them to make picture after picture, with greater long-term results for the leader. These leaders are known for their development of value in the market.

To develop value, it is important to make investments of three kinds of capital. The first, financial capital, are the funds needed to run a business. These funds are usually raised through public or private placements. The second is human capital—the individuals who create the ideas, make the decisions, and provide the professional services or selective experience to make a successful product launch through a disciplined marketing program.

But it is the third form that entertainment leaders use for exploration, analysis, and even implementation. It is called social capital—the relationships that exist among the veterans of the industry wars. Relationships are more important than title or money in the entertainment industry. Relationships create power and authority through the ability to get things done. Even when a recent project has failed, or a set of prior circumstances may not have been all they could have been, certain industry players can still get the green light based on who they know.

Nowhere is the old adage, “Be careful on your way up because you never know who you’ll meet on your way down,” more true than in this industry. A poker game at an executive’s home can often be as important as a major staff meeting at the studio. More than one major project has come about after a Friday night discussion of what movie to make, who to hire, and how to craft the financials.

In entertainment, there is little formula to fall back on and even less insight to the rapidly changing tastes of the market. Yet the leader must make consistently successful decisions—while dealing with pop culture and fickle loyalties at the box office/retail outlets/broadcast distribution points. No one can rely on history to assess and create the direction for tomorrow’s projects. The only history available is the amount of money a project made or lost, under whose guidance. Often, regardless of whatever may have come to pass during the actual production of an entertainment product, good or bad, it is that final report card—the money made—that makes the next project happen—that, and the relationships maintained.

The leaders that maintain these relationships manage the ultimate selection of the product. They employ vast numbers of creative people at salaries and perquisites that range from union-required minimums to the most extravagant levels that managers and agents can negotiate.

But it isn’t an easy ride, all glitz and glamour. The president of worldwide marketing, the president of production and distribution, the CEO of the studio must all have the ability to develop marketing strategies and implement the marketing plan under minimum input situations. Often there is only bare-bones research and budgets and timetables that are out of control. There’s often little room for error, careers on the line, and hundreds of millions at stake.

Yet decisions must be made and implemented—decisions that will make or break careers. When dollars are tight, some of these decisions may be affected by a true entertainment art form: the making of a deal.

Deal Me In

Deal-making is usually associated with the initial steps in formalizing a creative project and gaining financing. However, when it comes to creative marketing, deal-making proceeds as the producer or the director—or on occasion, the star—tries to usurp responsibility for the marketing message and even the selection of the media. If the team member has experience in this arena and knows when to push the right buttons, it can go very well. If nonmarketing professionals get involved with the marketing—to brandish their egos, burnish their images, or simply exercise power—the implementation can go wildly astray. This can lead to the wrong audience seeing a film. If that audience is disappointed and spreads negative word of mouth, a very big-budget movie can become a very big financial failure.

However, the right use of the deal is critical to success. Getting a star on the right primetime talk show requires deals to be made at the highest studio and network levels, especially when a star from one network is promoted on a talk show owned by another. Here is where contacts, relationships, experience, and public relations savvy become very valuable in the integration of the marketing communications plan.

Nothing in deal-making happens as a reflex. It is not “the way it has been done in the past” or “the way we have always done it.” Everything is negotiated, starting with the time an event should begin, the size of the budget, the people to be involved, the expected outcome, the titles or credits, and the friends who will receive some form of participation. Even the promotions department requires deals to be made to get sponsors or product placement people to provide items for free, funding for contests, sweepstakes, wardrobe, air tickets, limousine services, hotels, and catering. This is often where the true mettle of the marketing team member is tested: putting the package together with maximum effort and minimum cost.

Deal-making is also a specialty of the stars themselves. Big names can certainly have an impact on the green lighting of a project, but some ventures are still considered too risky for studios to undertake. When this occurs, there are other considerations that go into the making of a decision. If Barbra Streisand wants to make Yentl or Madonna wants to star in a third remake of Evita, the studio might need to maintain good relations with their music division and produce, finance, or at least distribute the project. It took almost 15 years for John Travolta, an acknowledged devotee of Scientology, to get a movie made from one of the books written by the deceased founder of the popular religion—a project that turned out to be a box office disaster.

The ultimate—and riskiest—type of deal-making is the grass-roots effort of an actor or actress who wants to promote him or herself in a personal project to increase his or her visibility. This is a labor-intensive, frequently frustrating experience for actors whose goal is to build a star role or platform. The actor may write the script and find the financing; that dedicated soul may also develop the marketing, advertising, and public relations in order to build an audience. The Big Night, written, produced, and starring Stanley Tucci, got Hollywood’s attention and built a fan base for Stanley, who soon after won roles in several movies. This type of self-marketing may include everything from the occasional billboard to attendance at every possible function, including film festivals and charity dinners. And then there’s the leading gossip columnists, who must be pampered.

If it works, it’s golden. If it doesn’t, it’s history, as might be the actor.

Generally speaking, the true artists of the deal—and the legends of Hollywood—are those superpowers who rise to the top of the industry through a combination of deals, talent, experience, and luck: the moguls.

Top of the Heap: The Moguls

Entertainment moguls have always been with us—stories of Louis B. Mayer and Daryl Zanuck abound, kingpins of the studios in the early days—but in today’s world, it takes a lot more than a studio chief to be considered a mogul. The growth of the entertainment industry, stretching out into all the platforms discussed in this book, has created a world in which true mogul-dom is conferred upon those who know how to tie it all together, creating endless streams of revenue for their mega-companies.

But it also takes a lot more than revenue to make an entertainment mogul. Apple may be on the brink of being the first company to be valued at over $1 trillion, but for the time being, its reach is well within the world of conduits, not content. Steve Jobs...rest his soul...would not be considered an entertainment mogul, though he certainly was a genius with technology, and understanding that design was the driver that whets the consumer’s appetite.

No, moguls in this industry are people who wield enough power and vision to create the giant companies that feed the public’s desire for all that drives the entertainment and media industry. But beware, you who aspire to these heights. The glare of fame and power can often hide the lights of the oncoming semi. Ask any one of the four moguls who were featured in the first edition of this book, a mere 10 years ago. All four powerful men, divining the future of the business, creating the very engines that have taken this industry to the over $1 trillion it takes in today, have fallen far behind the scenes.

Michael Eisner was booted from the board of Disney by angry shareholders, led by Walt’s nephew, Roy Disney. Michael Ovitz, forever linked to Eisner in a disastrous run as president of Disney, never reattained his position as the most powerful man in Hollywood. Barry Diller, dreams of a fourth network long gone, is busy redistributing the intellectual property of those that do exist—and making no friends in the process. And Gerald Levin? Well, that Time-Warner/AOL merger did get approved—and flamed out in a spectacular super-nova. Far from his old corner office, Levin—a distant memory—publicly apologized for the merger as late as 2010.

So, who shall we choose this time? Who stands at the precipice of power now?

And how will their reigns end?

Mega-Moguls

The events of the last ten years have left two true moguls standing. These men—Sumner Redstone and Rupert Murdoch—are old-school. Though both inherited businesses from their fathers—Redstone a theater chain in the Northeast; Murdoch, a daily newspaper in Australia—each built his empire over time, mashing together all sorts of elements, bundling and unbundling as new opportunities presented themselves, rising to the very top of the entertainment and media pyramid. In literature, men like these form the basis for thinly disguised characters in sweeping family sagas. They are both billionaires many times over.

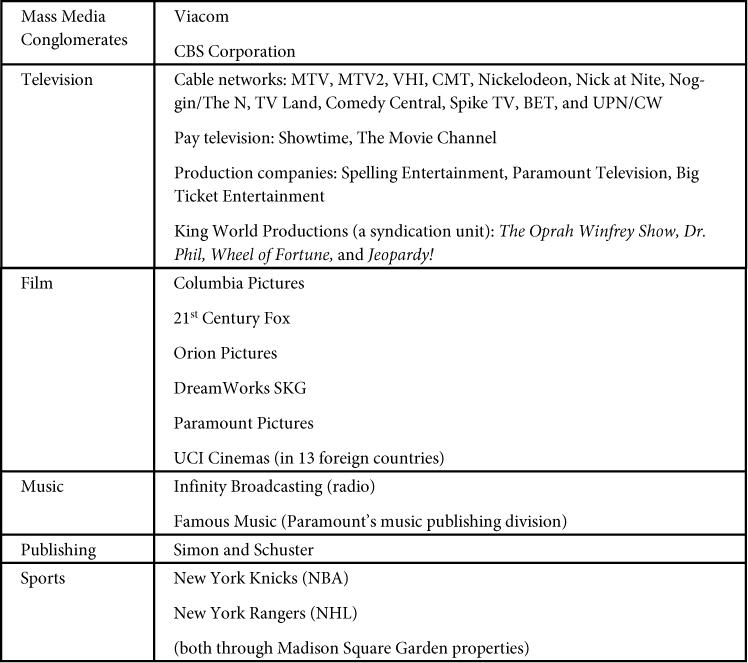

Redstone—the man who said “content is king”—practices what he preaches. Though he may not own or control all of the following now, over the course of his reign he has parlayed the many holdings listed in Exhibit 2-3, in addition to many others. He is the current chairman of both Viacom and CBS, which split from one another, as described earlier in this chapter. His personal chess game has knocked knights from their horses, and brought new kings to old networks.

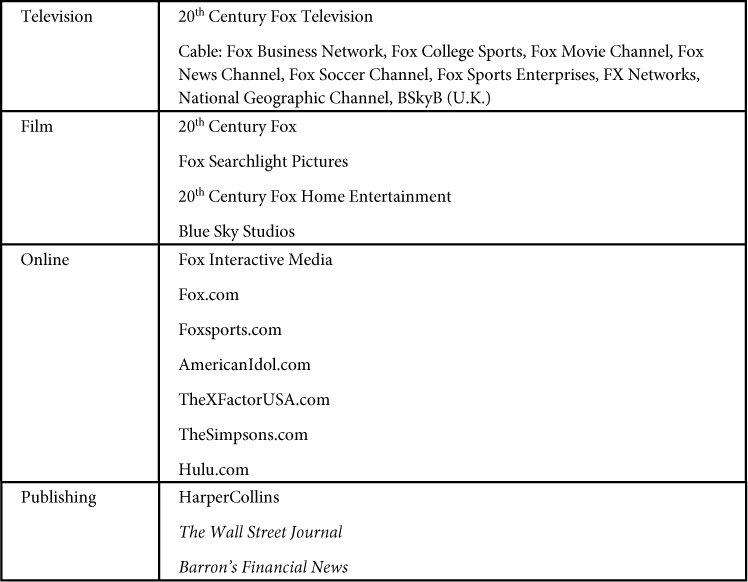

A partial list of Rupert Murdoch’s holdings includes filmed entertainment, television, online, and print media (see Exhibit 2-4).

Like the mega-moguls before them, neither has had an entirely smooth ride of all of this, notably Murdoch, with the News of the World phone-hacking scandal that shook the very roots of his British business dealings in 2011.

But we do not aim to add another commentary to the list of thousands that have been written on this situation, only point out that Redstone and Murdoch may be the last two men with such intimate knowledge and control of their businesses, having built them ground-up. They may be the very last of the old-style moguls, and for better or worse, they have changed the entertainment and media landscape forever.

Media Monarchs

Mogul-ness depends as much on personality as it does on holdings—the perception that this person has the vision and the nerve to create something bigger, shifting the destinies of the businesses and people they lead. To look for today’s power brokers, we follow the intersecting paths of entertainment, media, and technology—or convergence, which was described in Chapter 1, “Begin with the Basics: The What and Where of Entertainment Marketing.”

It is this intersection that creates the power that will continue to drive entertainment marketing. Content is useless without a conduit. Conduits are useless without content. Therefore, it is those industry leaders who bring the two together—the convergence—that get the nod for this edition.

Let’s divide the players via three of the Four Cs (keeping in mind that one C, consumption, has to do more with the choices the end-user makes to consume the media).

Content

Top of the List: Bob Iger, Disney

Iger stepped in to the vacuum left by Michael Eisner and quietly—in comparison to the man he followed—took this entertainment monolith to new heights. While steering a steady course for the Mouse, Iger resolved the thorny relationship with Pixar by buying the company, providing an excellent return for the company. Iger then showed his gumption with the acquisition of Marvel Entertainment. Though many in the industry thought he had overpaid (at $4 billion), the skyrocket success of The Avengers silenced the critics. As of September 2012, The Avengers box office stands at $1.5 billion. Who knows what windowing will add to this pile, and there’s no way to track the millions...or billions?...that licensing will bring. Iger then capped off his strategic run by buying LucasFilm, with all the glory of the Star Wars franchise, effectively buying a base of boys to complement Disney’s long-standing hold on princess-loving girls.

Perennial Evergreen(s): Harvey and Bob Weinstein, the Weinstein Company

After a 26-year run with Miramax—the last 12 under the ownership of the content king, Disney, the Weinsteins moved back to independence, founding their eponymous company in 2005. It’s hard to beat the brothers when it comes to sheer content, with their movies (The King’s Speech, The Artist, The Iron Lady, Silver Linings Playbook) constantly winning awards and accolades, not only from organizations but from the stars who work for them. But it’s more than their movie-making skill (and distribution deals, partnerships, and books); it’s the outsized personalities that fill any room they enter, demanding respect from all directions.

Conduit

Top of the List: Tim Cook, Apple

Much like Iger at Disney, Tim Cook has been handed the reins of what is arguably the biggest conduit company in the world. Apple continues to change the way technology is used, and therefore distribution is enhanced (or threatened, depending on which side of the intellectual property being played on the iPad you might stand). With a new smart TV project on the horizon, a successful patent infringement lawsuit against Samsung’s Galaxy on the books, and the continuing issuance of iPhones and iPads along with the sheer dominance of iTunes in the music distribution business, Apple—and Cook—may be on top for a long time to come. Can he out-Jobs Steve? Those are huge shoes to fill, and the competition is coming on very strong.

Finally Underway: Jeff Bezos, Amazon

In 1994, Jeff Bezos created an online bookstore, naming it Amazon partially to make sure the company name showed up early in alphabetical searches. When it went public in 1997, Bezos made it clear that he did not expect to turn a profit for several years. Stockholders complained that the company was moving too slowly, and when the dot-com bubble burst, all eyes turned to this upstart, wondering when the coffin would be carried out. Amazon seemed doomed to be just another punchline. But Bezos held on, broadening his offering beyond books, and turned his first profit in 2001—small, but a memorable milestone.

Today, online consumers can purchase nearly anything on amazon.com. Revenues exceed $47 billion, and the company is on track for $100 billion by 2015, mirroring the growth path of another American retail phenomenon, Wal-Mart. But more than this, amazon.com has defined online retailing, creating a comfort zone for consumers that has spread to other sites.

What truly brings Bezos to mogul status is his ongoing push into more than simply selling stuff. He pioneered e-books with the development of the Kindle and then decided to move past the middleman by developing online publishing, dealing a difficult blow to the already wobbling publishing industry. Amazon is also a major provider of cloud computing services, hosts websites for retailers such as Sears Canada, Marks & Spencer, and Lacoste, among others. The company also owns other online retailers such as IMDb (Internet Movie Database), Zappos (the shoe e-tailer), Reflexive Entertainment, a video game developer, and BoxOfficeMojo.com.

But in early 2013, Amazon announced its biggest entertainment venture to date. The company is now creating original content for its Amazon Prime Instant Video service, creating yet another competitor in the growing cord-cutting cable war.

Convergence

Top of the List: Jeffrey Bewkes, Time Warner

Like Bob Iger, Jeffrey Bewkes has come to his mogul-dom through a climb to the top of an already existing empire, and like his Disney counterpart, he’s doing a steady job of steering this ship. Time Warner is a multinational media company, with major operations in film, television, and publishing, including HBO, Time Inc., and CNN, along with New Line Cinema, Turner Broadcasting System, The CW Television Network, TheWB.com, Warner Bros., Kids’ WB, Cartoon Network, DC Comics, Warner Bros. Animation, and Castle Rock Entertainment.

We count Bewkes under convergence rather than content because Time Warner, up until Bewkes’s reign, seemed more focused on the pipeline than the content (especially with the disastrous merger with AOL, which he finally cleaned up in the last spinoff in 2009). But now Bewkes has publicly stated that he wants the new Time Warner to be a content company. Spending on content has jumped 7% annually since 2008 as Time Warner has shed costs in other areas.4 Given his track record at gold-standard HBO—his path to the top of the Time Warner ladder—Bewkes knows importance of content, so much so that he finally softened his stance on Netflix, putting together a deal with the streamer, even as his own HBOGo keeps its product close to home.

4 “Time Warner Trims Its Excesses,” New York Times, October 31, 2011.

However, his focus on content will not be extended to the magazine that launched the company. In early 2013, TimeWarner attempted to sell off its magazines, including Time, Sports Illustrated, Fortune, and Money, but when the deal with Meredith fell apart, the decision was made to spin the magazines off into a separate, publicly traded company. The end of an era—and another toll of the bell for magazine publishing.

Coming on Strong: Brian Roberts and Steve Burke, Comcast/NBC Universal

The deal spun between Comcast and GE for NBC Universal nearly defined the term convergence. Comcast, which controlled a lion’s share of the technology and conduit that feeds the American living room and home Wi-Fi networks, and NBC Universal, a top content provider, are now one company, an entertainment media giant with tentacles in all directions.

Brian Roberts, son of the founder, has spent his career with Comcast. Steve Burke came to Comcast in 1998, after a successful run with The Walt Disney Company (Disney Stores, ABC Broadcasting, EuroDisney). Under their watch, the company became the United States’ largest cable company, largest residential Internet service provider, and third largest phone company. Roberts is the chairman and CEO of Comcast and serves on the Board of Directors for NBC Universal. Burke serves as executive vice president of Comcast and CEO/president of NBC Universal.

Moguls as Mentors

Throughout these relationships, it is not only the moguls that ultimately affect the direction of the entertainment industry, but the people they mentor as well. The entertainment industry has a long list of mentoring moguls, people whose reign ultimately ended, but whose influence lives on. There is a continuum in the industry that reaches far and wide. This relationship network continues to bear fruit in the ongoing convergence. In many cases, it is the long-standing relationships of the moguls that bring these packages together.

Summary

As the entertainment industry has grown and the synergy between sectors has increased, the ability to make things happen, to break logjams, and to build effective teams has become increasingly important. Although the players of early Hollywood reveled in their power in the domestic film business, today’s mogul extends his or her reach well beyond the movies themselves. Through distribution, licensing, and sponsorship, entertainment moguls now direct international campaigns that move with the speed of an ever-widening pool of new technology.

But at the heart of it all, there is still that flickering image on the movie screen.