1. Begin with the Basics: The What and Where of Entertainment Marketing

Entertainment marketing, regardless of which platform we discuss, has some commonality with other industries. Licensing, merchandising, sponsorship, brand extension—all of these occur elsewhere, no matter what the product might be...that is, if you’re fully exploiting the profit potential of your product.

However, entertainment has some unique properties that affect the use and distribution of the brand. Before we go deeper into the unique worlds of each entertainment platform, let’s discuss the common threads that tie them all together.

The Four Cs

The structure that defines the whole of the entertainment industry can be described in four words, all of which begin with the letter “C”:

![]() Content: The actual entertainment product, from the initial idea to the finished offering, always creative-driven or -derived and occasionally manipulated with technology. The book, movie, song, game, experience—even a software package from the likes of Microsoft—ready to be delivered to the consumer.

Content: The actual entertainment product, from the initial idea to the finished offering, always creative-driven or -derived and occasionally manipulated with technology. The book, movie, song, game, experience—even a software package from the likes of Microsoft—ready to be delivered to the consumer.

![]() Conduit: The pipe through which the entertainment product flows to get to the customer: coaxial cable, Ethernet, Wi-Fi, television receive-only (TVRO) dish, ultra high frequency (UHF), very high frequency (VHF), digital transmission, the Internet. These pipes are not limited to electronics. In the entertainment world, product also flows to the customer through movie theaters, arenas, stages, or brand experiences—anything that carries the product to the audience.

Conduit: The pipe through which the entertainment product flows to get to the customer: coaxial cable, Ethernet, Wi-Fi, television receive-only (TVRO) dish, ultra high frequency (UHF), very high frequency (VHF), digital transmission, the Internet. These pipes are not limited to electronics. In the entertainment world, product also flows to the customer through movie theaters, arenas, stages, or brand experiences—anything that carries the product to the audience.

![]() Consumption: The form in which the consumer actually makes use of the product: the digital-download, CD, DVD, smartphone, tablet, personal computer, application, film, Internet-protocol (IP) enabled high-definition television, set-top box, the written page, or the live event.

Consumption: The form in which the consumer actually makes use of the product: the digital-download, CD, DVD, smartphone, tablet, personal computer, application, film, Internet-protocol (IP) enabled high-definition television, set-top box, the written page, or the live event.

![]() Convergence: The coming together of technology that enables the consumption of entertainment across multiple screens and venues, fed by digital transmission. Compressed data streaming everywhere, downloadable and consumable over a variety of devices. This might take place with an application that allows you to download a movie and send it to all of your devices—smartphone, PC, HDTV. Or in a digitally enabled theater, where you watch a live performance of the Metropolitan Opera while listening through the earbuds on your iPhone.

Convergence: The coming together of technology that enables the consumption of entertainment across multiple screens and venues, fed by digital transmission. Compressed data streaming everywhere, downloadable and consumable over a variety of devices. This might take place with an application that allows you to download a movie and send it to all of your devices—smartphone, PC, HDTV. Or in a digitally enabled theater, where you watch a live performance of the Metropolitan Opera while listening through the earbuds on your iPhone.

Each of the four Cs stands alone yet is fed by the others. Each of them offers a way to further exploit the initial idea, transforming that original thought into a product, a business, or a saleable commodity. Each involves some type of transaction with the consumer that calls for a well-developed, fully executable marketing strategy that will allow for the full capitalization of the idea.

The entertainment industry has a huge stake in each and every one of the Cs. Therefore, entertainment marketing must fully focus on

![]() What the consumer ultimately watches / listens to / reads / experiences

What the consumer ultimately watches / listens to / reads / experiences

![]() What form the content takes to be consumed

What form the content takes to be consumed

![]() What conduit the consumer chooses

What conduit the consumer chooses

![]() What mix of technology and media the consumer might use to create his or her own personal experience

What mix of technology and media the consumer might use to create his or her own personal experience

Think of it this way: It isn’t just the movie. It’s the consumer seeing it in a theater, on a DVD, via premium cable, or downloading it to a tablet. Or buying the electronic game based on it. Or purchasing the newly released Kindle version of the original book.

Entertainment is a hugely diverse industry with an equally huge opportunity to create income streams. And the marketing of that entertainment is the key to the vault. However, there is one huge challenge facing the entertainment marketing professional, a factor that is different from other industries: perishability.

Lightning in a Bottle

Entertainment is a luxury, not a necessity. Movies won’t give you a dependable ride to work, and a downloaded song won’t feed your family for a week. People will only consume entertainment when they have time, money, and the desire to do so. That desire comes about through any number of variables, but once it’s there, you’d better deliver—now. Entertainment must be available to the public when the public wants it, not a minute sooner or a second later.

It is this perishability that poses the biggest challenge to the industry. Trends in automobiles or home furnishings—large investments—may ebb and flow over several years. Those industries can follow a linear path in the life of a product, taking more time to create the new version, model, style. Entertainment? Today’s hot thing can be cold as a clam tomorrow. The consuming public is fickle, so if you want to take advantage of their interest, you need to mobilize all your forces immediately.

This wasn’t always so. In the early days of mass entertainment, when a much smaller investment might have been at stake, products were often carefully nurtured, strategies tested and retested. But in today’s incredibly fast-paced world—with consumers tweeting, YouTube-ing, and texting their opinions—managing buzz is like holding on to a lightning bolt. Every entertainment product is in a race to the finish line from the moment the light goes green.

That “wanna-see, wanna-read, wanna-watch, gotta-hear” marketing produced for the launch of a product can mark the difference between success and failure. To grab the public’s interest, the promotions that create these compelling messages cannot wait until the launch of the product. They must simultaneously weave in and out throughout the process of production, distribution, and consumer transaction.

And, all of this must happen at every step of every extension of the brand to fully maximize the product’s potential. Again, it isn’t just the movie (song, book, team, electronic game); every other product associated with or spun off from the movie (song, book, team, electronic game) must be addressed as well.

So where do we start the process of creating entertainment? With content.

The First C: Content

If marketing is the key, content is the coin. All entertainment starts with content. The term “content” covers everything that happens to produce the actual entertainment product that is ultimately delivered to the consumer in one form or another.

Even though the idea for content might possibly come from the mind of one person, it takes an army of dedicated professionals to craft that idea into a product that hits the market at just the right time, in just the right form, with exactly the right buzz to grab the lion’s share of the consumer’s disposable income and discretionary time.

Creating content is a multilayered process, much like an onion. Like said onion, it’s hard to peel one bit without grabbing part of the next, but in general, there are four elements in content, regardless of which sector of entertainment we’re discussing. They include

![]() The development of a creative idea to prime the pump or start the production process

The development of a creative idea to prime the pump or start the production process

![]() The endorsement and utilization of technology to help complete the production

The endorsement and utilization of technology to help complete the production

![]() The use of talent to act in or flesh out the idea and make it work

The use of talent to act in or flesh out the idea and make it work

![]() The perishability of the product, given, as discussed, that time is always of the essence due to changes in consumer trends and tastes.

The perishability of the product, given, as discussed, that time is always of the essence due to changes in consumer trends and tastes.

Planting the Seed: The Creative Idea

Without Walt Disney’s initial creation of Mickey Mouse, there would be no Disneyland, Walt Disney World, Tokyo Disney, EuroDisney, Disney Cruise Line, Disney on Broadway, Disney books, videos, games, T-shirts, coffee mugs, designer furniture, stuffed animals, or Disney Happy Meal toys. Somewhere along the line, there has to be the heart of the movie, the book, the script, the score—the creative idea. Oh, and if there’s a cute little furry something that can be morphed into a billion products, so much the better.

In today’s entertainment world, the creative product is often an outgrowth of a strategic research process that has minutely identified a market, like a vein of ore waiting to be mined. The strategic development (SD) team at any major entertainment provider is often the initiator of what will ultimately become a new product or destination. Millions of dollars and thousands of hours might have been invested in a concept long before the actual creative process fully begins. SD, which typically has a full-time staff as well as outside consultants, carefully examine the market demographics, competition, impact on brand identity, development cost, and ultimate return on investment in a search for new revenue streams.

This initial investment, however, does not guarantee that a product will ever come to market. More often than not, a concept is shelved when the idea being researched proves to be either unprofitable or not profitable enough. Disney, for example, believes that a new product line (for example, a Disney Theatrical Group or Cruise Line) must ultimately become a billion-dollar—that’s right, billion with a “b”—revenue stream to be seriously considered. Although some products and concepts might be launched because they extend the brand equity, each project is minutely researched and can even come to fruition in terms of a product rollout, only to be shuttered if full-profit expectations are not met.

But none of this investment—either from a strategic development perspective or the simple act of a singular idea that slips in as a no-brainer product—would be worth a cent if it could not be protected in some way. Thus, we come to the most important aspect of content: the ability to legally protect it and to create ownership.

The process of establishing ownership is known as copyright.

Copyright

In the late 1970s, when the movie industry finally awoke from its glitz-induced slumber (probably aided by the sound of a thousand MBAs thundering up the road, swarming to save several bankrupt studios from complete annihilation), the new business-based management focused its full concentration on copyright. The bottom line was this: Without copyright, there is no entertainment industry—for there is no legally protectable product that can be bought, sold, licensed, leveraged, extended, and otherwise shaken by the ankles until every penny drops out of its pockets into the hands of the investors.

This focus on copyright dovetailed with the passage of the Copyright Act of 1976, which gave creators and their assignees exclusive rights to reproduce, distribute, and make the most of other uses of their original works. With the passage of this act, made necessary by changes in technology and global usage, copyright also applied to much more than traditional writings; it now protected motion pictures, videotapes, sound recordings, computer programs, databases, and many other original creations, including artwork and sculpture. Additionally, certain works were now exempted from copyright protection—in particular, works of the U.S. government.

As a result, contracts flowing from within all areas of the entertainment world now contain phrases such as “intellectual property,” “work product,” and “work for hire.” All of these terms define the who, when, why, and where of idea or concept ownership—that an idea itself can be owned by a person or an entity (and not necessarily by the actual creator of the same), and therefore not copied in any form or fashion by anyone else—including that creator—either for fun or for profit.

The ownership of ideas and concepts is a complex and important subject, given copyright allows for the syndication of TV shows, the licensing of brands, the sale of sports paraphernalia, or the inclusion of comic book characters on lunchboxes (or in mega-blockbuster movies and their endless string of sequels). Creativity might be the soul of entertainment, but copyright is the key to the cash.

The exploding growth of global entertainment creates new challenges to face in this area. Although digital streaming has allowed for faster transmission to markets around the world, it has also opened the doors to piracy. Copyright is recognized in the courts of many established countries, but emerging markets often lie outside those confines. In addition, the Internet has created a country of its own—the Wild Web—where nearly anything goes. Entertainment companies must be constantly on the alert for those who would steal their protected content and bootleg it.

From a marketing perspective, the ballyhoo has already begun at the creative stage of content—whether it’s news about what major star has been signed for what upcoming blockbuster movie, which must-read author has holed up to pen another tale, what software giant is working on the latest version of the hottest game—the machine is cranked up to whet the consumer’s appetite. This part of the campaign might be relatively low-key—a PR placement here or there, a one-sentence insertion in People, a small post on Facebook—in case the project takes a turn.

Now that the creative and copyright elements have joined together to begin the content process, the product must now be filmed, animated, scripted, recorded, promoted, and shipped out the door to be experienced by the customer. So on to the next layer of the onion.

Production

The production phase includes everything it takes to produce the best book, movie, home video, downloadable song, network TV or cable show, radio program, electronic game, or any other of a myriad of packaged or preproduced entertainment products. This would include the launch of a new ride or exhibit at a theme park, the completion of a state-of-the-art movie, or the final burnishing of live theater.

Again, this is not linear—the project can swing back and forth from the creative stage to production throughout these first two steps, whether for rewrites, legal challenges, or a change in players. This can be especially true concerning shifts in talent in film, given that each new player who comes to the table might require a slightly different approach to his or her character—and that character’s interaction with other characters—both of which are highly dependent on that new player’s position in the Hollywood pecking order.

Marketing is in serious swing by this point in the project, especially as production moves closer to release. The idea is to build up the desire of the public to see/hear/read the product so that by the time it’s finally poured into its respective conduit, the public is in a lather, waiting at the other end to be showered with the latest release.

The Second C: Conduit

Conduit, the distribution of an entertainment product in a high-tech age, refers to two elements of the delivery process: the where and the how. In simple terms, the conduit is the actual process by which a product is distributed, as opposed to the consumption (coming later in this chapter), which is the final form in which the consumer receives the product. For example, think of a theater as the conduit and the exhibition of a movie as the consumable.

Ten years ago, when we wrote the first edition of this book, we wrote—with great sagacity—that big box retail was the big winner in the race for retail, severely damaging the Mom and Pop Shops. We believed that only the big chains would succeed with a public that wanted more, faster, at less cost.

Though we were smart enough to make a few prognostications on the Internet that did come to pass, we stand amazed by the speed at which this conduit has changed the industry. Tower Records? Virgin Records? Gone. Barnes and Noble? Still hanging on by its fingertips, but the competition—Borders Books—gone. Even Loews and the other theater chains are doing their best to keep people coming to the movies instead of waiting for the movies to come to them.

In their place we have Amazon.com, not only selling books by the zillions, but publishing them, both hardcover and Kindle versions. iTunes owns the music download business. Netflix is busy tucking everyone into their home media rooms with pay-for-play movies, broadcast network series, cable programs, and now, their own original content. Digital transmission, streaming away, is putting a whole new spin on all forms of retail, and UPS is having a field day.

The Internet has brought innovation to every corner of our lives, changing the way we do business, learn, and communicate in a profound manner. We have yet to know the full scope of its impact. But as we’ve said: the Internet is not entertainment. It’s just another pipe. A really amazing pipe with an incredible reach, but a pipe, nonetheless.

Of course, the old conduits are still in place—movie multiplexes, broadcast and cable television, live theater, radio, satellite dish, direct marketing catalogs—and still deliver the lion’s share of content to the consumer. But the Internet is more than a technology shift; it’s a lifestyle shift, so we have yet to see how any or all of these traditional delivery systems morph.

The Third C: Consumption

The consumption phase is the point at which the finished entertainment product has been offered to the public. Effective advertising, as part of a fully integrated marketing program, results in a transaction—someone paying for and consuming the product. The consumption phase is when the marketing rubber really hits the road, where the marketing executive depends on his or her ability to successfully lure the consumer.

The transaction could be buying a ticket at the local cinema; viewing episodes of a TV series on Netflix; listening to satellite radio; clicking the channels on a set-top box; downloading a book to a Kindle, Nook, or iPad; or for the old-fashioned, purchasing a book at a local bookstore. Or it could be a visit to a live concert, where 100,000 fans are motivated emotionally and physically by pulsating laser lights, incredibly loud music, and the sense of sharing it all with their fellow devotees.

In the U.S., there are five major television broadcasting networks,1 1,781 television stations,2 280 cable networks,3 39,000 movie screens,4 15,256 radio stations,5 13,000 newspapers,6 and 24,000 magazines7 for people to consume. There are hundreds of electronic games, both hard copy and mobile. We have yet to identify the number of new, old, and classic CDs, books, newsletters, live concerts, Broadway shows, off-Broadway shows, summer theaters, nightclubs, and theme parks to enable the consumer to feed his or her entertainment habit.

1 http://benton.org/node/65435.

2 http://transition.fcc.gov/Daily_Releases/Daily_Business/2013/db0412/DOC-320138A1.pdf.

3 www.ncta.com/About/About/HistoryofCableTelevision.aspx.

4 www.natoonline.org/statisticsscreens.htm.

5 http://transition.fcc.gov/Daily_Releases/Daily_Business/2013/db0412/DOC-320138A1.pdf.

6 www.stanford.edu/group/ruralwest/cgi-bin/drupal/visualizations/us_newspapers.

7 www.magazine.org/insights-resources/research-publications/trends-data/magazine-industry-facts-data/1998-2010-number.

The typical American annually watches 1560 hours of television (across all platforms),8 listens to 880 hours of radio,9 and spends 176 hours reading newspapers10 and 120 hours reading magazines.11 We are a consumer society, and we consume entertainment with abandon across a wide variety of platforms and technology.

8 http://blog.nielsen.com/nielsenwire/online_mobile/report-how-americans-are-spending-their-media-time-and-money/.

9 www.radioinsights.com/2010/04/how-much-do-people-listen.html.

10 http://paidcontent.org/2011/04/29/419-infographic-how-print-vs-online-news-consumption-compares/.

11 http://techcrunch.com/2010/12/15/time-mobile-newspapers/.

But the most important point? It’s all available at the same time.

This is the underlying challenge of entertainment marketing. Your target consumer is not simply waiting around for your product. Your consumer has literally thousands of entertainment choices to fill his or her time with. You are competing with each and every one of them, all the time.

After work and sleep, consumers have roughly 62 hours per week to spend on anything else—including entertainment. You are competing for every single second of that discretionary time.

And what’s driving the number of consumer choices through the roof?

The Fourth C: Convergence

From both technology and content standpoints, convergence is the true wave of the present and the future. Convergence is the coming together of technology that enables the consumption of entertainment across multiple screens and venues, fed by digital transmission and compressed data streaming, which is downloadable and consumable over a variety of devices. This convergence has created a boom in the marketing of entertainment, and it has made the consumer king (or queen).

According to Nielsen research, Americans spend more than 41 hours per week watching video across the screens.12 But how they’re consuming content—traditional TV and otherwise—is changing. Demonstrating that consumers are increasingly making Internet connectivity a priority, 75.3% pay for broadband Internet (up from 70.9% last year); 90.4% pay for cable, telephone company-provided TV, or satellite. Homes with both paid TV and broadband increased 5.5% between December of 2011 and December of 2012. This number continues to rise in 2013.13

12 “Free to Move Between Screens, The Cross Platform Report”, Nielsen, March 2013

13 http://blog.nielsen.com/nielsenwire/online_mobile/report-how-americans-are-spending-theirmedia-time-and-money

At the heart of convergence is the ability to create, transmit, and capture all information—movies, art, music, news—in a digital format. After that information has been reduced to the ones and zeroes of the digital world, it can be transmitted over any available form of the latest technology via satellite broadcast or cable transmission. Wired or wireless, the ability to move information fluidly from point to point has created a new world of information, entertainment, and services.

With thousands of choices at their fingertips, fed through any number of devices, consumers now fully control their entertainment options. They decide what, when, and how. Gone are the days where a studio could assume that consumers will go to a theater to watch the latest release. Theaters are still holding their own, but there is a growing segment of the market who is happy to wait for the premium cable or Netflix release to view a movie in the comfort of their own super-charged media rooms, with mega-sized HD-3D TV, surround sound, theater-style seating, and really great popcorn (with real butter). Or on their tablet. Or on their smartphone.

Note that the consumer is still paying for the movie. The transaction is still taking place, but the venues and devices have changed, which opens whole new fields of discovery and opportunity for the entertainment marketing professional.

What does all of this mean to the entertainment world, outside of the ability to move content digitally? Most important is the variety of conduit channels that are now available. As a simple example, consider the following statement: “I watched ESPN last night.” The entertainment marketing professional has to ask: Were you watching ESPN or ESPN2? Were you watching it on your television, or were you viewing it on a closed-circuit broadcast at the ESPN Zone down the street? Or were you viewing it on espn.com? On what? Television? Smartphone? Tablet? Laptop? And how? Via the Internet (either wired or wireless) or mobile?

Oh, and what other technology were you connected to while you were watching? Were you texting? Tweeting? Emailing? On Facebook, “liking” what you were watching, along with the rest of your friends?

Have I managed to reach you? The entertainment marketer ponders this question and more, trying to find the very best way to the pocketbook of that overloaded consumer. Riding the waves of discretionary time, disposable income, and expanding technologies, marketing teams must build brands, develop audience awareness, create need versus want, and leverage the brand to the nth degree, utilizing every avenue possible to create an ongoing income stream.

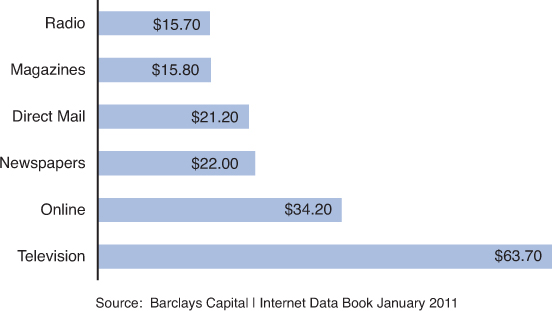

In fulfilling that mission, billions of dollars are spent to reach that coveted consumer (see Exhibit 1-1).

Do take note: Television spending is still—by a long shot—the big winner. The Internet is coming on strong, but it will take a bit more time to have the reach of TV. But another up-and-coming challenger is on its way. Mobile advertising topped $4 billion in 2012 and is expected to exceed $7 billion in 2013. If this trend continues, it may hit $21 billion by 2016.14

14 www.emarketer.com/newsroom/index.php/unexpected-growth-facebook-google-lead-significant-uptick-mobile-advertising-us-market-share/

This is the heart and soul of entertainment marketing: identifying unmet needs; producing products and services to meet those needs; and pricing, distributing, and promoting those products and services to produce a profit.15

15 This is opposed to advertising, which is a paid form of communicating a message by the use of various media, generally persuasive in nature, or public relations, which is a form of communication primarily directed toward gaining public understanding and acceptance, usually dealing with issues rather than products or services.

Successful marketing is the product of a carefully orchestrated attack, and often in today’s entertainment industry, that attack comes from a multitude of directions, stretching the brand—the original idea, the original content—into a variety of products and revenue streams. Those streams spread across a wide web, producing returns at all levels, in all dimensions:

![]() The marketing of the original content: The movie, the book, the song, the game.

The marketing of the original content: The movie, the book, the song, the game.

![]() The development of the relationship between the consumer and the original content that helps to sell another product: The sale of a McDonald’s Happy Meal, driven by the Finding Nemo toy inside.

The development of the relationship between the consumer and the original content that helps to sell another product: The sale of a McDonald’s Happy Meal, driven by the Finding Nemo toy inside.

![]() The utilization of marketing within the media: The creators who make money from the original concept; the cohort that makes money from retailing (the toy company that makes the Nemo toy and McDonald’s selling the Happy Meal); and the conduits that charge to carry the content and extract a fee from consumers to consume it (cable companies, Netflix, and so on). These are the people who remonetize the original content.

The utilization of marketing within the media: The creators who make money from the original concept; the cohort that makes money from retailing (the toy company that makes the Nemo toy and McDonald’s selling the Happy Meal); and the conduits that charge to carry the content and extract a fee from consumers to consume it (cable companies, Netflix, and so on). These are the people who remonetize the original content.

![]() The use of entertainment to sell new hardware: Hardware allows entertainment to be used anywhere, at any time, by any consumer, in any form that they want: televisions, tablets, smartphones, laptops.

The use of entertainment to sell new hardware: Hardware allows entertainment to be used anywhere, at any time, by any consumer, in any form that they want: televisions, tablets, smartphones, laptops.

Licensing, Merchandising, and Sponsorship

Whatever the approach, the ultimate payoff of this synergy is the creation of the three most conspicuous revenue streams evolving directly from the entertainment and media businesses: licensing, merchandise retailing, and sponsorship. Each acts not only as a revenue stream, but also as a marketing strategy—marketing that more than pays for itself. As always, there are several ways to measure the success of these supplementary revenues, either as separate categories related to the entertainment and media sectors or as a percentage of all sales, both domestic and international.

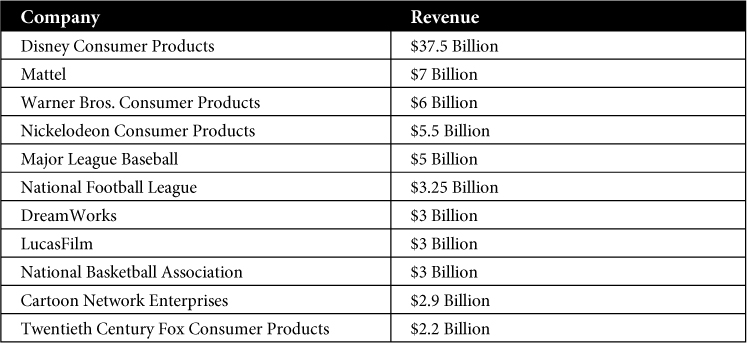

For example, worldwide licensing in 2010 was estimated at more than $192 billion.16 Although this total represents a wide variety of market segments, entertainment companies rank high in the listings of the top 125 Global Licensors. Consider the estimated revenue licensing brings to the following entertainment brands, as shown in Exhibit 1-2:

16 License!Global magazine, May 2012.

Exhibit 1-2 Entertainment Licensing Revenue

Source: License!Global magazine, May 2012

Consider this: Licensing is profit, pure and simple. When the lawyers have agreed on terms, the money flows back to the owner, with no other real investment.

Synergy also happens through deals with companies outside the parent company’s umbrella. Additional licensing can come from other forms, including household products, general merchandise, packaged goods, private-label store brands, and fashion designers.

In fact, the fashion industry is often represented as a close cousin to the entertainment industry. Fashion shows are staged like Broadway opening nights, with fabulous sets and the most current hit music driving the display of beautiful models—some of whom eventually realize their ambition to act in major motion pictures. The fashion business has also been well-integrated into the media, as it uses public relations, music videos, magazine covers, and product placement to burnish the brand—while adding to the bottom-line profitability of the entertainment product being utilized.

Fashion circles back around to join the entertainment industry in the growth of entertainment-related sponsorship sales. We find fashion icons like Hilfiger, Lauren, and Armani sponsoring major music concerts, film premiers, sports contests, product placement within network TV and cable shows, film festivals, and Broadway openings.

Continuing in a synergistic vein, consider the liquor, soft drink beverage, and fast food industries, which are certainly interested in their stockholders’ satisfaction and aggressively chase sponsorship and its important promotion subset, product tie-ins.

Most important, revenue from licensed products can cover the sins of box office failures, protect the funds needed to invest in new properties, and maintain shareholder value in a highly volatile and competitive segment of the world economy.

Another lesson to be learned from this group of self-promoting, income-generating vehicles is that licensing, merchandising, and sponsorship have the added benefit of being marketing tactics in and of themselves. Any marketing professional alive would give a year’s salary to have millions of consumers wearing his or her brand to schools, to the park on weekends, while shopping in the malls, lying on sheets, using towels, drinking from glasses—all with brand reminders. The buying and wearing of licensed products promotes the movie, the series, the team. They also look good on special-events ties, T-shirts, and expensive jackets. These products are live billboards that provide an implied endorsement, maintaining brand awareness and credibility.

Branding is a serious program and a commercial support system that is well worth the planning and involvement of marketing teams that can envision the future, even in the face of artistic criticism. Herein lies the separation between the art film or independent movie made as a statement of the director’s life view as contrasted with a film that is made for pure mass audience engagement with the prospect of a huge return on investment.

But branding is not only about momentary profits—it is a long-term strategy that can pay off handsomely over the years. A classic brand, sustained for 30 or 50 years, still as fresh and productive as when it was first invented, is a perfect example of value in equity. Franchises like Peanuts, Superman, Batman, and yes, all those Disney characters (we know you’re tired of hearing about Disney, but did you notice who the gorilla at the top of that chart was?) are often the pillars of major media companies, or at least the support of a division. They can be expected to perform financially every time they are brought out and relaunched for a new audience.

The good times will continue to roll as long as there is disposable income to fuel the purchases and discretionary time to enjoy the ever-growing portfolio of entertainment choices. Although movies themselves may be a relatively small part of the overall revenue stream in the entertainment industry, films are still the center of the entertainment universe, creating the launch pad for the remaining platforms: video, retail, DVD, books, magazines, electronic games, and more.

Now that we’ve defined the structure—on with the show!

Summary

Content, conduit, consumption, and convergence: These four elements form the basic structure of all entertainment products. However, because entertainment is generally based on a creative idea, the glue that binds the industry together is copyright, which gives the content-holder the ability to create protectable revenue streams, such as licensing and sponsorship based on the product.