STEP THREE

Manage Scope Creep

OVERVIEW

Stakeholders Providing inputs

Project Objectives

Project Scope and Scope Diagrams

Stakeholders Receiving outputs

We've all done it; in fact, I just did. Here I sit, determined to make some progress on this book, phone call, and all the intrigue happening at the coffee shop I'm visiting. Distraction is a kind of scope creep—easily succumbed to and difficult to avoid. With our mobile email and phones, we're in touch with everyone everywhere 24/7. It's always tempting to get pulled away by something new and exciting, or something old and ugly.

In project management, scope creep is the number-one killer of success. Inevitably, you'll start a project with certain parameters, and then it begins to grow, morphing into something bigger. This type of scope creep usually doesn't happen with a big decision or a loud confrontation; it happens quietly, one small concession at a time. Someone you like asks you to make a simple addition to your work that won't take you any time at all. Uh-huh. Before you know it, your tiny, simple project has become mission critical and due tomorrow.

Who creates scope creep? We all do. Project managers blame the stakeholders for changing their minds, but constant changes in business dictate that the stakeholders will have new requirements throughout the project. Stakeholders blame project team developers—IT programmers who grow enamored of some fancy new technology that isn't really imperative, or graphic designers who spend additional hours unnecessarily tweaking cool animation. And, ironically, project managers can expand the scope by doing a good job of communicating because better information helps stakeholders think of factors they didn't consider before. And, you know what happens then.

In no time

at all, Speedy had finished his house. All that remained was a final inspection to see that he'd done everything he needed to do to protect himself. Sitting on his porch and tapping leftover sticks together, he noticed that different sticks made different, almost musical sounds. He had a wonderful idea—he'd get his brothers to form a band with him! All thoughts of his house and a final once-over flew out of his head as he turned his attention to gathering lots of unusual sticks to make new sounds and amaze his brothers. What a pity! If he'd paid more attention to his building, he'd have noticed that the top wasn't hooked into the four walls.

Meanwhile, Goldy ran out of straw—all the pieces he'd found on the ground had covered only half a house. He knew he could go to town and buy some straw, but that seemed extravagant. He wandered around, searching for things that would work like straw and not cost him anything. He gathered small pieces of paper, a tin can, a dead but leafy branch, and his favorite find—a giant piece of cardboard.

As Demmy went down the road to town, he stopped to talk with people he knew, asking their opinions about where to get the best bricks. With his friend Bob, he had a long talk about the history of brick as a building material, and they agreed it was important for Demmy to spend some time online researching types of brick before he chose his own. So off he went to the library.

Scope creep isn't a bad thing. But it must be managed. In fact, managing the change in scope as a project progresses is an important part of the manager's role. Scope will evolve continually. Many people have the impression that project management means controlling or eliminating scope creep—but that's completely wrong. If a project is going to continue to provide the business benefit detailed in the business objectives drafted and documented in Step 2, it has to evolve over time. If you could finish a project in several minutes or even a few days, you might have a fighting chance of starting and ending with the same scope, but most projects take much longer than that. And the longer the project takes, the more the scope will change, of course.

It does seem like I've just argued both sides of the scope creep dilemma—down with distractions and endless alterations and up with evolution! Here's the point. Scope creep kills a project only when the stakeholders, including the project manager, don't agree that the scope has changed. The big problem occurs when the scope has changed and the project sponsor doesn't think it has. The project team has more work to do but the sponsor expects it to be done with the resources originally assigned (time, people, and money).

Scope creep, when managed well, is a productive change process, ensuring that the project ultimately will meet the needs of the business. For everyone to be in agreement about what changes have been made and what the impact of these changes will be requires that

![]() the scope is defined and agreed to before the project starts

the scope is defined and agreed to before the project starts

![]() any changes to the scope are added to the scope definition and agreed to before they are scheduled

any changes to the scope are added to the scope definition and agreed to before they are scheduled

![]() changes to the scope are reflected in realistic changes to deadlines, budget, and people time.

changes to the scope are reflected in realistic changes to deadlines, budget, and people time.

The business objectives, established in Step 2, help prioritize some of the scope changes. In this step, you'll create project objectives that are the criteria all will use to measure the final project results. As project manager, you'll use these project objectives as a contract with your stakeholders. But words on a page are not as meaningful as a picture, so here you'll also learn how to draw a picture of the scope so that scope communication is easier and everyone stays on the same page.

When you first meet with the sponsors and stakeholders, their natural focus will be on what they'll get when the project is complete. In a way, it doesn't matter to them who you'll have to work with to get to that point. The stakeholders are the people who provide you with the inputs you need and/or request something from the project. The scope of the project, then, is the point at which these inputs and outputs touch a stakeholder. Put another way, I can create a blog for an external customer to use, but within the scope of that blog-creating project, I can't make the customer use it. The stakeholders represent an imaginary set of fence panels around the project, and what is enclosed by those panels is the scope.

Time to Complete This Step

After you've gathered the information you need, expect to spend less than one hour writing the project objectives and one hour drawing the scope diagram. How long it takes to gather the information will depend on how many stakeholders you have to question. Bringing your stakeholders to consensus on the project objectives and scope diagram could take a significant amount of time, depending on how hard it is to get people to attend meetings or respond to email in your corporate culture. If the project really is needed by the sponsors, you should be able to get consensus on these within a couple of weeks.

Stakeholders

All stakeholders should be involved in the scope discussion if possible, facilitated by and including the project manager (you). Tool 3.1 shows the process I've found most useful for gaining stakeholder consensus about project objectives and the scope diagram. If you adopt this process early and use it regularly, it will teach the sponsors and stakeholders what you'll require from them throughout the project.

Questions to Ask

At this point, if you're working on a business-related project, ask the stakeholders Who will provide necessary guidance to the project team while we build the solution. Who are the subject-matter experts? Does one trump another? This information often is called the “project requirements,” and it represents what I am calling one kind of “input” to the project. Sample questions to use in identifying the other types and sources of project inputs are offered in Tool 3.2

TOOL 3.1

Steps to Gaining Consensus among Stakeholders

- Research (without interviewing) any sources and materials that will help you create good, rigorous questions to ask when you meet with sponsors and stakeholders.

- Meet individually with each sponsor and stakeholder, and ask your questions. Explain when you will send them a prototype of the project scope information, and by what date you would like to receive their revisions and suggestions.

- Summarize the results of all your sponsor/stakeholder meetings and prototype the project scope information.

- Send your prototype to the sponsors and stakeholders, with a reminder of the return date.

- Gather their responses—and nudge as needed to hit the dates you 've specified.

- If necessary, negotiate critical differences of opinion among sponsors and stakeholders.

- Publish the project scope information with credit to each of the sponsors and stakeholders.

TOOL 3.2

Questions Concerning Project Inputs

- Who will provide the requirements—that is, the specifications or details about what 's ultimately needed at the completion of the project?

- Who will be writing the check for the work? Who manages the project 's budget?

- Who will tell the project manager what processes or standards are to be followed?

- Who will provide the technology needed?

- Who will provide the people to work on the project, if needed?

- Who will do the design work?

- Who will do the testing or compliance work?

You'll also ask yourself, who or what will receive information and deliverables from this project? These “outputs” could be final products of the project but might also be interim information or prototypes developed as the project progresses. For example, it would be a good idea to send a list of the project objectives to the stakeholders for approval before moving along with the project—that list would be output. Tool 3.3 provides a few sample questions to help you describe and direct the outputs expected from your project

POINTER

Give It a Try

Try asking the inputs and outputs questions about one of the projects you're managing right now. What did you discover you hadn't thought of before?

To illustrate typical answers to questions posed in your search for input and output information, let 's consider our blog project and ask the questions in tools 3.2 and 3.3. I 've compiled a set of answers for you in example 3.1. At first glance, this project appears pretty simple, but as questions are raised, you can see in Example 3.1 that there are very important things that aren't clear. For example, the question of how the blog will be transferred from the development team to the person monitoring it will be critical to successful implementation. No decision has been reached

TOOL 3.3

Questions Concerning Project Outputs

- To whom will the project reports be delivered?

- Who will receive the final project deliverables?

- Are there any systems with which the project must build interfaces?

- Who will do the training for the rollout when the project is completed, and what will they need to have for the training?

- Who will handle marketing/sales for the rollout, and what will they need for that?

EXAMPLE 3.1

Blog Project Answers to Input and Output Questions

Project description: For our software development company, create a blog to answer customers' frequently asked questions.

Inputs:

- Who will provide the requirements—that is, the specifications or details about what's needed?

We will use Google Blog services. There is no pertinent expertise in the company, so we will learn how to do it through the Google Blog website.

- Who will be writing the check for the work? Who manages the project's budget?

The marketing VP has agreed to pay for 10 hours of one person's time to do this project, and to dedicate a person 1 hour per day to monitor this blog. There is no other budget money for this.

- Who will tell the project manager what processes or standards are to be followed?

We will use our normal time-tracking system to report actual hours spent on this project. No extraordinary processes or standards are required.

- Who will provide the technology needed?

We will use existing technology.

- Who will do the testing or compliance work?

The marketing VP will accept the final version of the blog. He will assign a staff member to do the final testing. There are no compliance issues. about who will have the final say on the finished products. People like to start projects on an agreeable note, so these types of pivotal questions often are avoided and neglected.

Outputs:

- To whom will the project reports be delivered?

The marketing VP will receive usage statistics at the end of each week from the person monitoring the blog.

- Who will receive the final project deliverables?

The marketing VP and the person in charge of monitoring the blog will be taught how to view and maintain the blog.

- Who will do the training for the rollout when the project is completed, and what will they need to have for the training?

The project manager will do all development work, including the training mentioned above.

Let's return to our family deck-building project for a moment. Imagine how talking over the specifics of project inputs and outputs before the project begins will maintain harmony among all those involved. There will be fewer but similar inputs questions, and you'll notice that each primary question generates an additional, deeper question:

1. Who will provide the requirements of the project?

1a. Who decides how big the deck will be, what type of wood will be used, the final design?

2. Who will be writing the check for the work? Who manages the project budget?

2a. Where will this money come from—cash? home equity loan?

3. Who will tell us what processes or standards are to be followed?

3a. Are there times when the construction should not be done—at night? before what hour in the morning or on weekends? Will the garage be used to prep materials? For how long will that area be needed?

3b. Do we need any permits? Where do we get them?

4. Who will provide the technology needed?

4a. Will we need to buy/rent tools? What kind and where?

5. Who will provide labor?

5a. Who will help us? How available are they?

And here are some pertinent outputs questions:

1. To whom will the project reports be delivered?

1a. How will we measure progress?

Many relationships could be saved if couples used these kinds of simple questions to prompt a discussion before projects begin!

Project Manager's Toolkit: Project Objectives and Scope Diagram

Scope can be documented using the left (analytical) and right (visual) parts of your brain. In this step, you create project objectives (left brain) and a scope diagram (right brain).

Project Objectives

Project objectives are the written criteria against which a project's final deliverables are judged. They define how a finished project will? be measured in terms of time, cost, and quality. Most projects have several or many objectives.

The most common guideline used for writing objectives of all kinds is the SMART approach. Tool 3.4 shows the characteristics of SMART objectives. You have asked the questions by this point and have lots of data from sponsors and other stakeholders to build your initial prototype of project objectives. Example 3.2 presents sample blog project objectives.

Scope Diagram

After you've collected the answers you need, you're ready to draw the picture. In that it focuses on where the project's boundaries are, a scope diagram is like a plat map of your property. Primarily, as with the questions asked earlier and the project objectives, the diagram helps you define for stakeholders the inputs and outputs the project will need to be successful. It also identifies which stakeholders will supply what inputs and which stakeholders will receive what outputs. Essentially, it clarifies everyone's responsibilities and expectations at the outset.

TOOL 3.4

Characteristics of SMART Project Objectives

![]() Specific: The objective tells exactly what, where, and how the completeness of the project deliverable will be measured.

Specific: The objective tells exactly what, where, and how the completeness of the project deliverable will be measured.

![]() Measurable: The objective states exactly how the project deliverable will be quantified—how much, how many, and how well.

Measurable: The objective states exactly how the project deliverable will be quantified—how much, how many, and how well.

![]() Action-oriented: The objective uses “activity indicators” to ensure that something will be done. Use action-oriented verbs such as deliver, implement, establish, and supply to define how the project will present the expected results.

Action-oriented: The objective uses “activity indicators” to ensure that something will be done. Use action-oriented verbs such as deliver, implement, establish, and supply to define how the project will present the expected results.

![]() Realistic: The objective is a result that can be achieved in the time allowed and with the resources supplied.

Realistic: The objective is a result that can be achieved in the time allowed and with the resources supplied.

![]() Time-bound: The objective includes a specific date by which it must be achieved.

Time-bound: The objective includes a specific date by which it must be achieved.

EXAMPLE 3.2

Blog Project Objectives

![]() A prototype blog website with 90 percent of all planned features and information will be available for testing 20 days before the launch date.

A prototype blog website with 90 percent of all planned features and information will be available for testing 20 days before the launch date.

![]() The blog site will be hosted through the free service Google Blog so it will be available to customers 99.5 percent of the time.

The blog site will be hosted through the free service Google Blog so it will be available to customers 99.5 percent of the time.

![]() In a customer focus group, 80 percent of the customers surveyed will rate the usefulness of the site greater than 7 out of 10.

In a customer focus group, 80 percent of the customers surveyed will rate the usefulness of the site greater than 7 out of 10.

![]() All customer responses, comments, or other blog information will be monitored and proctored through an IT resource before being made available to other customers on the site.

All customer responses, comments, or other blog information will be monitored and proctored through an IT resource before being made available to other customers on the site.

![]() An email link for comments will be included at the bottom of each blog page, and all visitors who submit a comment via this link will receive a personal reply within one business day.

An email link for comments will be included at the bottom of each blog page, and all visitors who submit a comment via this link will receive a personal reply within one business day.

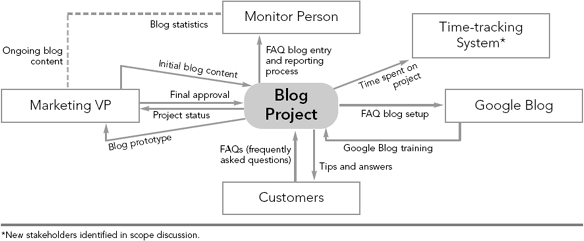

Let's use example 3.3 to illustrate a scope diagram. As we talk about how to read it, you'll be learning how to draw a diagram for your own project.

The rounded rectangle in the center is the project itself. Start there. It's too early really to know all the activities that will have to happen to get the project done, so at this point there's no detail about tasks inside that rectangle.

The squares surrounding the rectangle are the stakeholders. Every stakeholder identified for the blog project in Step 2 has his or her own square on this diagram. That's also true of each person mentioned in the answers to questions asked earlier in this step. (Note: Be sure to add those people to your stakeholder list, too.) Notice that stakeholders are not only specific people. Sometimes the square may name a role or position (for example, marketing VP), a department or team (accounting), an external entity (Google Blog), or an application (time-tracking system).

POINTER

Artificial Project Objectives

Don't let creating project objectives become an academic exercise. Objectives don't take a lot of time to write, but it does take time to write them well. Avoid the temptation to show your brilliance by using big words that don't communicate fully, or by putting in artificial measurements (for example, the customer will find the item he wants in 3.2 seconds). It's impossible to make the objectives perfect this early in the project. Try to capture 80 percent of what the project will do and continue to update and develop the list as the scope changes.

EXAMPLE 3.3

Blog Project Scope Diagram

Lines connect inputs from a stakeholder to the center rectangle, with arrows indicating the direction of flow. Likewise, lines connect project outputs to recipient stakeholders, with arrows showing the flow from the center rectangle to the receiving square. Each of the lines is labeled with the input or output flowing along it. When you construct your diagram, if you've already done more work on defining your objectives, you may want to use those objectives to draw the output arrows first. After that, look carefully at those output arrows and ask yourself, what else has to happen? That will prompt thoughts about other outputs and all of the inputs needed to produce them.

You'll have to make some decisions about granularity—what level of detail you show. You don't show every little input and output detail on this chart. For example, I try to avoid showing a request for information to a stakeholder (output); instead I prefer to show just the flow of the information back to the project (input). You're beginning to illustrate, at a high level, how your stakeholders will measure the success of the project. For example, “FAQ blog entry and reporting process” as an output to “Monitor Person” is a pretty general but important deliverable, and its arrow indicates a significant process handoff from the project team to the person who will monitor the website from implementation forward. There's going to be a lot to these process definitions that are transferred over, but at this point the label serves simply to show the significance of the Monitor Person as a stakeholder and to identify the type of flow to expect.

Here are some tips about drawing a scope diagram:

![]() Don't use double-headed arrows because it buries too much detail. It usually means you are showing that you've requested something and received it. These actually are two different flows and, as mentioned earlier, it may be that it's not necessary to show the request. There is almost no chance that whatever is going from the stakeholder to the project will go back to the stakeholder unchanged. If it wasn't changed, why was it needed?

Don't use double-headed arrows because it buries too much detail. It usually means you are showing that you've requested something and received it. These actually are two different flows and, as mentioned earlier, it may be that it's not necessary to show the request. There is almost no chance that whatever is going from the stakeholder to the project will go back to the stakeholder unchanged. If it wasn't changed, why was it needed?

![]() Usually there are inputs from and outputs to the same stakeholder, but it is possible for a stakeholder to be only a supplier or a receiver (for example, a customer).

Usually there are inputs from and outputs to the same stakeholder, but it is possible for a stakeholder to be only a supplier or a receiver (for example, a customer).

![]() Don't draw lines between stakeholders. As project manager, you can't monitor, control, or always know about flows between stakeholders, so don't try to document it. If you document it, you'll own it—and that creates scope creep. If illustrating such a flow is necessary to clarify some aspect of the project, show it with a dotted line rather than a solid line (as shown in example 3.3, from the marketing VP to the person doing the monitoring). This makes it clear that it takes place, but that it isn't in the scope of the project.

Don't draw lines between stakeholders. As project manager, you can't monitor, control, or always know about flows between stakeholders, so don't try to document it. If you document it, you'll own it—and that creates scope creep. If illustrating such a flow is necessary to clarify some aspect of the project, show it with a dotted line rather than a solid line (as shown in example 3.3, from the marketing VP to the person doing the monitoring). This makes it clear that it takes place, but that it isn't in the scope of the project.

![]() Create the diagram on a flipchart page and carry it around to show people. Don't draw it on the computer (weird, huh?). When people see a beautiful computer picture, they don't think they can disagree with it, but people feel very comfortable changing something on a flipchart. It's better to know early what they're going to change.

Create the diagram on a flipchart page and carry it around to show people. Don't draw it on the computer (weird, huh?). When people see a beautiful computer picture, they don't think they can disagree with it, but people feel very comfortable changing something on a flipchart. It's better to know early what they're going to change.

Using your own project and worksheet 3.1 as a practice template, build a scope diagram. Share it with others who know what's involved in the project, preferably stakeholders. What do you learn in this activity that you never thought of before?

Communication

It's important that all stakeholders, especially project sponsors, review the project objectives and the scope diagram to ensure that they are accurate and complete. Avoid the temptation to email the objectives to your stakeholders. If they're busy, most people will agree without really reading them. Because, ideally, you're going to be making in-person visits to present the scope diagram and explain its symbols, you might as well present the objectives at the same time. This kind of interaction provokes the most thoughtful exchange with stakeholders. In the real world, a brief meeting may not be possible, however, so here are a few ideas for getting the project objectives and the scope diagram validated:

![]() Create the project objectives prototype and distribute it through email for feedback. Use these objectives to draw a prototype scope diagram.

Create the project objectives prototype and distribute it through email for feedback. Use these objectives to draw a prototype scope diagram.

![]() Explain the scope diagram in a brief presentation. Walk the stakeholders through the diagram and get their feedback about its accuracy. Update the project objectives from this feedback

Explain the scope diagram in a brief presentation. Walk the stakeholders through the diagram and get their feedback about its accuracy. Update the project objectives from this feedback

![]() When the scope diagram and the project objectives have been updated to reflect the stakeholders' feedback, send both documents out to the stakeholders for a final look.

When the scope diagram and the project objectives have been updated to reflect the stakeholders' feedback, send both documents out to the stakeholders for a final look.

Any changes to the scope should be added to the project objectives and the scope diagram, with the sponsors' permission. When added, new objectives will either be accompanied by more money or time, or will be accompanied by the removal of other project objectives they replace.

POINTER

Advantages of the Scope Diagram

![]() Pictures speak a thousand words. All stakeholders would rather review a picture with you than a document set in 10-point Times Roman.

Pictures speak a thousand words. All stakeholders would rather review a picture with you than a document set in 10-point Times Roman.

![]() Drawing the inputs and outputs provokes new questions and new clarity.

Drawing the inputs and outputs provokes new questions and new clarity.

![]() Sharing this graphic representation with stakeholders helps them better understand the complexity of the project.

Sharing this graphic representation with stakeholders helps them better understand the complexity of the project.

![]() If you have multiple stakeholders, seeing the many flow lines helps them see why it isn't just all about their needs and their resources.

If you have multiple stakeholders, seeing the many flow lines helps them see why it isn't just all about their needs and their resources.

As we discussed earlier, novice project managers look for ways to freeze the scope of the project from the beginning. Your job is a lot easier if you can guarantee that the scope won't change, but you can't. Business doesn't work like that. Scope will change because business changes all the time. The diagram helps the project manager manage the change; it doesn't help refuse the change. The stakeholders get to decide what stays and what goes, and this diagram facilitates that conversation.

Communication is the essential purpose of this diagram. As the scope changes throughout the project, this graphic representation can be adjusted so that everyone understands the choices that were made. It's an evolving element of the project.

You will realize the value of this scope diagram later in the project when, well down the road, someone suggests an additional requirement. If all the parties have seen and agreed to the scope diagram in the beginning, you, as the manager, have a tool to use in negotiating revisions in a nonconfrontational manner. Without the diagram, such discussions tend to become blame focused—”I told you it was in there; you just forgot it!” With this diagram you can help the stakeholder understand the impact of the change and make the best choices for the business.

What If I Skip This Step?

It's amazing how tempting it is not to clarify the scope. When I teach our project management simulations, it's very common for students not to ask when they don't understand the scope. When pressed, many people say they didn't have time to work out the scope. What they're saying is that is makes more sense to do a project wrong quickly than do it right with less of a jackrabbit start. Most stakeholders probably would not agree with that conclusion.

When we discuss the tendency not to ask or not to plumb a little deeper at the outset, most people confess that they're afraid they won't like the answer. That takes us right back to our Step 1 discussion about who owns the project. Not asking the questions, not considering the answers, not defining the boundaries lets you as project manager make the scope whatever you want until the project is about 80 percent done. If you haven't given them the chance before, suddenly the stakeholders tell you what they want and you're tossed into crisis mode, reorganizing and reworking. Remember, the sponsor owns the project and stakeholders define it. It's the stakeholders who will judge its success at the end. The more channels of communication you establish and travel in the beginning, the more likely it is that they'll get what they expect and be happy when the project is complete. Skipping this step is just shooting yourself in the foot.

The scope diagram also helps you jump-start some project work you'll be doing in future steps: For example,

![]() The more stakeholders (squares) you have, the more project risk you face because of increased communication. You'll use the information portrayed in the diagram to prepare for those risks and to build future communication plans.

The more stakeholders (squares) you have, the more project risk you face because of increased communication. You'll use the information portrayed in the diagram to prepare for those risks and to build future communication plans.

![]() The diagram illustrates which stakeholders are most crucial to the project—they're the ones with the most arrows. Understanding their significance is a great help in building a communications plan.

The diagram illustrates which stakeholders are most crucial to the project—they're the ones with the most arrows. Understanding their significance is a great help in building a communications plan.

![]() Each arrow represents at least one project activity (most likely, more than one). Realizing that will help you jump-start brainstorming the tasks for the project as you build a project schedule in Step 6.

Each arrow represents at least one project activity (most likely, more than one). Realizing that will help you jump-start brainstorming the tasks for the project as you build a project schedule in Step 6.

Lurking Landmines

![]() You ask too many questions and add scope to the project. As you get the answers to your questions, keep comparing them to the original business objectives from Step 2. It's tempting to expand the scope of the project while defining it, but try to resist that temptation.

You ask too many questions and add scope to the project. As you get the answers to your questions, keep comparing them to the original business objectives from Step 2. It's tempting to expand the scope of the project while defining it, but try to resist that temptation.

![]() Different stakeholders want different things. This diagram is great for showing all the stakeholders the full picture, so it's an asset when one stakeholder doesn't know what the other has asked for. Use your intuition—if it starts to feel like you're trying to do more than one project under the guise of a single project, use the diagram to question that approach. From a risk perspective, two tightly focused projects have more chance of success than one large, vague project.

Different stakeholders want different things. This diagram is great for showing all the stakeholders the full picture, so it's an asset when one stakeholder doesn't know what the other has asked for. Use your intuition—if it starts to feel like you're trying to do more than one project under the guise of a single project, use the diagram to question that approach. From a risk perspective, two tightly focused projects have more chance of success than one large, vague project.

Step 3 Checklist

![]() Ask good questions and create a list of project objectives.

Ask good questions and create a list of project objectives.

![]() Identify the sources of the inputs to your project.

Identify the sources of the inputs to your project.

![]() Identify the recipients of the project outputs.

Identify the recipients of the project outputs.

![]() Draw a scope diagram showing stakeholders, inputs, and outputs.

Draw a scope diagram showing stakeholders, inputs, and outputs.

![]() Review project objectives and scope with all stakeholders, revising them until you achieve consensus (or at least compromise).

Review project objectives and scope with all stakeholders, revising them until you achieve consensus (or at least compromise).

The Next Step

In the next step, you'll learn how to predict the project risks and build contingency plans to meet them. When you've completed the work of Step 4, you'll be ready to start the project.