STEP TEN

Follow Up to Learn Lessons

OVERVIEW

Post-Project Reviews

A Learning History

Sticky-Note Analysis

Appreciative Inquiry

Web Surveys

Nominal Group Technique

When the project is over you'd like to think about something else. Your entire team feels the same way and, in the hallway, stakeholders are avoiding eye contact with you. The last thing anyone wants to do is revisit the project and its missteps, bad choices, delays, conflicts, and weak outcomes. No one even wants to bring up the good parts—the happy surprises, the mended relationships, the amazing saves, or the deep friendships. But there is gold in all those hills, and the last step in successful project management is to find it and mine it.

Years ago, I was the leader of the IT subproject on a large project that was highly time constrained and very visible to our external customers. It was politically charged, and we dared not fail. The end product was a two-week customer event at pre-Olympic trials. Among other things, we had to deliver sports tickets, hotel rooms, meals, shows, and transportation. From the perspectives of sponsor and customer, the project was a success. From the teams' perspective, there were some big problems. It was in this project that I first saw the value of holding a post-project review.

When BB opened

the diner door and let in the three little pigs, everyone at the counter turned around, surprised to see this group come in and sit together as friends.

As the four ate their pancakes, they talked about all they'd been through together.

“You know, fellas, my family got into the huff-and-puff business when they passed that law about not eating chickens,” BB told them. “Chickens were our bread and butter, and they took that away. Knocking down your houses wasn't personal—it was survival.”

The pigs told BB about their three strategies for building shelters. Speedy said he'd moved too fast because he couldn't believe BB would be coming after him. In his hurry, he veered off course and slapped together a house that didn't meet his original goals. And then he got distracted by the sticks and the music he could make with them.

Goldy admitted that he'd made a few mistakes of his own. He moved too slowly, looking for the cheapest way to get something done. He'd found free straw—but not enough of it. It was too late to get more straw, so he'd used scraps of trash to finish his house. His original plan wasn't solid, and the makeshift result was far from stable.

Demmy was glad his house had saved them, but he said he knew there were flaws in his approach, too. He'd been so caught up in building the perfect house that he was paralyzed by planning. When he finally began to build, it was almost too late. And the roof was such an afterthought that without his brothers' help, it never would have held.

So, they'd all learned some lessons:

- Balance speed, cost, and quality for any project because focusing on just one will generally make you fail.

- A little planning and “what-if” thinking really helps.

- Three pigs are better than one.

- Collaboration is the path to success. Both BB and the three little Oinks had a problem. And when they listened calmly to one another, they found a way to solve it so everyone was satisfied.

Emotions were high during the project. One project manager oversaw project leaders heading six different subprojects, and everyone lived in different states. For all of us, our project responsibilities (presented to us as a “great career opportunity”) were in addition to our regular jobs.

As the project started to hit snags, strategic alliances began to develop, roles became murky, and at least one person didn't pull his weight. We all grew angry about the shirking, and a few of us went to the project manager to ask that he do something about the non-performer. He did nothing, and if you'd asked me then what the major project problem was, I'd have told you we had a weak and ineffective project manager because he wouldn't control the team.

Three months after the project ended, we met again as a team. Prior to that meeting, we each put our thoughts about the project on paper and emailed them to the project manager. Although I don't remember ever seeing the results of those emails, it forced me to take a careful look back at the project. From three months out, my opinion had changed. To my surprise, I realized that when the project manager refused to solve our team issues, he helped the project tremendously. If we had had to depend on him to monitor and manage our relationships, we never would have met our project goals. Instead, we were forced to take care of the shirking problem ourselves, often picking up the dropped work. In fixing the problem, we kept the project on track. I don't know if the project manager did this on purpose, or if it was his natural style and just lucky for this project. Either way, it worked. It was a lesson that I try to remember on my own projects because I tend toward micromanaging.

What's meaningful about that story here in Step 10 is that I would not have learned that lesson if I hadn't taken the opportunity to reflect on the completed project from the vantage point of a little time and distance. What nuggets can you learn from your previous project experiences? Learning theory and knowledge management research have shown that people can't learn on a macro level while they're in an experience. Learning occurs after the experience is over when they think about what happened.

POINTER

It's tough to get people to participate in a review unless your company has a pertinent and enforceable policy. Even if no one else is able to participate, give yourself an hour to think through the lessons learned on the project. Ask yourself these questions:

1. What went well on this project? What would I do again on future projects?

2. What did not go well on this project? What would I change on future projects?

Simply becoming conscious of what did or didn't work will improve your ability to manage projects successfully.

We are at the last phase of our Dare to Properly Manage Resources Model. In this step, we focus on Review. You'll learn about both the value of and processes for facilitating a post-project review. If possible, find a quick and simple way for all participants to share their thoughts about the project. Obviously, you have to have a pretty tough skin to ask for feedback, but it's well worth it. If they won't participate, do a post-project review yourself. Learning still will occur.

Time to Complete This Step

A post-project review can take anywhere from 30 minutes to two days. If you're doing it by yourself, you can grab a cup of coffee and think about the project for 30 minutes or so. If you're doing the review through a facilitated session with a large number of stakeholders, it can take from one to two days, depending on the techniques used and the number of participants.

Stakeholders

If you can get all of your project's stakeholders to participate in a post-project review, it's a tremendous gain for everyone. All of the perspectives that will be represented at the table offer a rare 360-degree view of the project. The sponsors will see the project from a different viewpoint than the stakeholders and the project team members. And they'll all see it somewhat differently from the way you see it.

Questions to Ask

Questions can be simple and wide ranging or pointed and more deeply revelatory. On the simpler side are these two questions:

1. What went well on this project? What would I do again on future projects?

2. What did not go well on this project? What would I change on future projects?

These questions are open-ended and can be used for sponsors and stakeholders who won't be able to commit much time to a review. The questions are also excellent for leading a discussion face-to-face with the project team. By leaving the discussion more open, you'll get very different responses from different people, and those responses will trigger great learning.

For a more pointed review of the specific aspects of your project, use the questions in tool 10.1 with members of the project team and with stakeholders who were more involved in the work. If the project was larger and more complex, thus meriting more review time and investment, use these more probing queries. These questions also may produce better responses than the more open questions when the review is not going to be done face-to-face.

Project Manager's Toolkit: Techniques for Post-Project Reviews

Companies serious about growing project management competence keep the project lessons learned in a searchable file. Keeping a knowledge base of these data requires a commitment of time, database expertise, and business intelligence expertise. Investing in this type of knowledge base provides the company with a way to learn from actual results. These results can be used to jump-start new project teams, which improves project results dramatically. The project management office is a good place for this activity to be housed.

Example 10.1 lists some of my favorite learning nuggets from reviews I've done for clients. Use this list to jump-start your next project.

Depending on the size and risk of your project and the current time commitments of the people whose participation you'd like to engage in your review, choose among the following approaches when holding a post-project review:

![]() face-to-face versus virtual meetings via phone, webinar, or email

face-to-face versus virtual meetings via phone, webinar, or email

![]() discussions versus individual surveys

discussions versus individual surveys

![]() mixed groups versus subteams focused on one aspect or activity of the project.

mixed groups versus subteams focused on one aspect or activity of the project.

TOOL 10.1

Questions for a Thorough Review

1. How close to the scheduled completion date was the project actually finished?

2. What did we learn about scheduling that will help us on our next project?

3. How close to budget was the final project cost?

4. What did we learn about budgeting that will help us on our next project?

5. What did we learn about communication during the project?

6. At completion, did the project output meet client specifications without additional work?

7. What, if any, additional work was required?

8. What did we learn about writing specifications that will help us on our next project?

9. What did we learn about staffing that will help us on our next project?

10. What did we learn about managing conflict through negotiation on this project?

11. What did we learn about monitoring performance that will help us on our next project?

12. What did we learn about taking corrective action that will help us on our next project?

13. What technological advances were made on this project?

14. What tools and techniques were developed that will be useful on our next project?

15. What recommendations do we have for future research and development?

16. What lessons did we learn from our dealings with service organizations and outside vendors?

17. If we had the opportunity to redo the project, what would we do differently?

EXAMPLE 10.1

Sample Lessons Learned in Post-Project Reviews

1. You can never ask too many questions.

2. Trust your instincts.

3. The more you can help people focus on one task, the more velocity your project can maintain.

4. Hand-offs kill.

5. During times of trouble, more communication is better than less.

6. Without project management documentation and process, everyone depends on the project manager to answer all their questions and direct them. For small projects, you might be able to depend on a single person to keep all the project knowledge in his or her head, but for a medium-size to large project, it isn't feasible.

7. No project will be perfect.

8. No issue is insurmountable if you're creative enough.

9. Projects generally don't fail because the project definition is faulty or the project schedule is inadequate. Projects fail because people fail to communicate.

10. Investing in structured processes, rules of order, and roles to make your meetings effective is an important way to improve the odds of project success.

In planning your review, remember that the more diverse the groups involved, the better the results—but there's also more risk of conflict. Think about how you'll gather the lessons learned and how you'll share the results after you've synthesized everyone's responses.

How Long Should You Wait Before Conducting a Review?

I've found that post-project reviews are most effective when they occur between three and six months after a project is completed. Such a pause ensures that the project is really over, but isn't so long that people really can't recall details. The trick to successfully timing the review is to get far enough from the day-to-day action of the project that your participants have a more holistic view of it, but not to wait so long that the details are gone.

What Can You Do at the Post-Project Review?

If you have the luxury of face-to-face meetings, you can do the post-project review and celebrate the successful completion of the project in the same event, and you should do both. This works well for very large projects that were geographically dispersed. It may take a few months to get the relevant players together. The added benefit is that a “celebration” tends to trigger better participation than a more serious-sounding “post-project review.”

If possible, find as a facilitator someone who wasn't directly involved in the project. (It's also good if meeting participants don't work for the facilitator.) If it's impossible to find someone to facilitate, the project manager may end up playing that role.

In either case, simply leading an open discussion without a structured facilitation approach is generally not an effective and safe way to gather lessons learned. There can be a lot of charged-up feelings waiting to explode, and there may be people who don't feel their views are important to anyone else. Using one of the facilitation techniques described below will promote equal participation. In addition, these facilitation techniques will be different enough from the normal project meetings that participants will be unable to fall into their old communication patterns. This tends to make the discussions not only more safe, but also more open. Consider using one, some, or all the following techniques.

Learning History

Use this technique where there were some major conflicts on the project that have never been discussed fully. This technique offers a safe way for participants to reveal the emotional baggage they carried from the project, and it helps keep them from lugging that baggage to future projects. The technique comes from the field of knowledge management, and the process is described in tool 10.2.

TOOL 10.2

Steps of the Learning History Review Process

1. Ask everyone to type up a one-page description of the project, viewed from their perspective. Ask them to tell a story of something that happened that they believe is indicative of things that happened throughout the project. Each person will have an individual story that's extremely meaningful to them. In some cases, the stories involve big wins, but most often the stories will focus on things that didn't go well for the writers.

2. Ask each participant to email her or his one-page “learning history” to the facilitator. Explain that copies will be made for other participants.

3. At the group meeting, the facilitator hands out copies of the stories so that all attendees can read along as each person reads his or her story aloud.

4. After each story, other participants are invited to ask clarifying questions about the story.

5. When the questions have been discussed, the facilitator asks the group to brainstorm lessons, and then lists them on a flipchart. This same process is repeated for each story. When all stories have been read and discussed, review the lessons listed on the flipchart.

A learning history is a stunningly effective technique for revealing feelings. People write and then read stories about the project with greater honesty than they normally would share in a forthright discussion format. Good facilitation is critical, and it may be important to lay out some ground rules at the beginning. No person may be victimized or ridiculed for his or her honesty. The discussion that follows each reading must be controlled so that it doesn't become a debate over the accuracy of the story. Remind the participants that what each story reveals is the writer's perception of reality, and it may or may not be the same reality others perceived.

After everyone has had a turn, review the flipchart list of lessons learned, removing and combining them as the group suggests to make a concise list that can be shared with others.

Sticky-Note Analysis

Use this technique when a great deal of conflict still exists among the participants. This approach will allow differing opinions to be expressed anonymously. The technique works well as an opening facilitation approach when followed by a different technique that drills down further into the specifics of the conflict, like the learning history technique.

Tool 10.3 describes the process for sticky-note analysis. As with the learning histories, the products of this review are documented lessons learned.

Appreciative Inquiry

Use this technique when the project team has worked really hard and been very successful but hasn't been recognized for their effort or the project outcome. Often, teams that have a major disaster and then recover are recognized more than teams that stayed the course and finished well without a major incident.

There are many resources available—especially on the web—to help you facilitate this technique. Here we'll use a basic approach, described in tool 10.4. The idea behind appreciative inquiry is to look for the positive rather than the negative aspects of a successful project. In identifying what factors supported and promoted specific and overarching successes, participants discover how to repeat these successes in the future. The energy of discussing and learning from the positives is a wonderful way to learn from each other and celebrate project completion.

Web Surveys

Use web-based surveys when you need to gather lessons learned without revealing respondents' identities or when respondents are dispersed geographically and unlikely to come back together. There are inexpensive ways to do web surveys that make it easy to gather and summarize information, including www.surveymonkey.com or www.freeonlinesurveys.com. Use these tools to create one of the following:

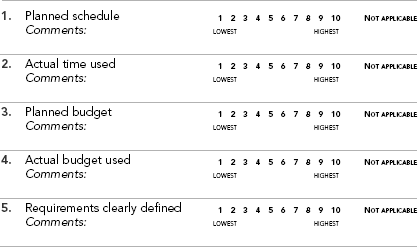

![]() Simple survey (sometimes called a “smile sheet”): In this type of survey, you list the issues on the project that you believe will be important to the participants. Then, you ask each participant to rate the importance of the issue numerically—for example, from Not Important (1) to Extremely Important (5). Using a numeric ranking approach makes it easy to summarize large amounts of data. However, if you find out that an issue has been rated low, it's difficult to understand why people feel that way. Tool 10.5 is a sample survey of this kind.

Simple survey (sometimes called a “smile sheet”): In this type of survey, you list the issues on the project that you believe will be important to the participants. Then, you ask each participant to rate the importance of the issue numerically—for example, from Not Important (1) to Extremely Important (5). Using a numeric ranking approach makes it easy to summarize large amounts of data. However, if you find out that an issue has been rated low, it's difficult to understand why people feel that way. Tool 10.5 is a sample survey of this kind.

![]() Emotion-based survey: In this type of survey, participants are asked how they feel about the project success, and then asked why they feel that way. Through this approach, participants generate the issues they feel merit discussion. By starting with emotions, people tend to list the things that really affected them. The strength of the emotion is used to prioritize which issues really affected the project team. This type of survey is more difficult to construct and summarize using simple survey tools, but web versions are available (for example, see the Clarity survey at www.russellmartin.com). Tool 10.6 offers some typical items from a survey of this type.

Emotion-based survey: In this type of survey, participants are asked how they feel about the project success, and then asked why they feel that way. Through this approach, participants generate the issues they feel merit discussion. By starting with emotions, people tend to list the things that really affected them. The strength of the emotion is used to prioritize which issues really affected the project team. This type of survey is more difficult to construct and summarize using simple survey tools, but web versions are available (for example, see the Clarity survey at www.russellmartin.com). Tool 10.6 offers some typical items from a survey of this type.

TOOL 10.3

Sticky-Note Analysis Review Process

Use these questions for this review technique:

![]() What went well on this project? What would I do again on future projects?

What went well on this project? What would I do again on future projects?

![]() What did not go well on this project? What would I change on future projects?

What did not go well on this project? What would I change on future projects?

Listed below are the steps to follow in facilitating this review.

1. Provide pencils and a pad of same-color sticky-notes to all participants.

2. Ask each participant to answer the questions about what went well on the project by writing one thought per note. Allow enough time for participants to keep writing until they've answered the questions as fully as they can. What usually works for this is to wait until about 80 percent of them are obviously finished and then announce that 30 seconds of writing time remains. Tell them to place their piles of notes in front of them.

3. Repeat Step 2 with the questions pertaining to what didn't go well.

4. Group the participants into teams of three to five people. Assign each group a specific area on the wall, and ask them to put all their individual sticky-notes up on that area without speaking to anyone else while they do it. This will take only a couple of minutes. They should remain at the wall until they're finished placing their notes.

5. With the same team of people, before the team members have time to start looking at each other's notes, ask them to begin—again silently—grouping similar notes together. Tell them they may move any note they wish (not just their own). At this point, people lose track of who wrote what, and that maintains the anonymous feel of this exercise.

6. Gently reinforce the silence of this part of the exercise, and let the grouping continue until about half the teams seem to be finished. This normally takes 5–10 minutes.

7. Ask participants to continue grouping for two more minutes, now letting them talk to each other. This enables them to clarify the groupings they've already made.

8. Give each team one pad of notes of a different color. Ask the teams to use these notes to label each grouping.

9. Ask each team to tell the entire group how they labeled their note groups and to read some of the details on the notes. When a team is done explaining its results, ask the group to brainstorm and share lessons learned from that team's work and to list the lessons learned on flipchart paper.

10. Conclude this review by asking each person to share what he or she thinks is the most important lesson. Record this by putting a checkmark next to that lesson on the flipchart page. This can also be typed up and distributed electronically to the participants and to future project managers.

TOOL 10.4

Appreciative Inquiry Review Process

Depending on the size of the group, break into teams of three to five people. Appoint a leader for each team, using strange criteria like “the person with the oldest car.” Explain that each team will follow this process:

1. The leader will ask each team member to share a story about a success on the project. Each person will take up to five minutes to tell the story. The others can ask questions.

2. Then the leader will ask the team to revisit each of the stories and define what it was that caused the success. Some examples might be good communication, strong leadership, innovation, and so forth. The team leader will document these causes on a flipchart or on note paper. Many stories will have similar causes.

3. The teams will be brought back into one large group, and the team leaders will share their lists while the facilitator writes the items of all the lists on a flipchart.

4. The group will discuss what steps to take on future projects to ensure that similar successes occur. In other words, they'll describe how to create an environment for success.

Nominal Group Technique

This technique leverages the power of email to gather information. You can use it when you don't have time to meet with everyone or they don't have time to meet with you. Use this technique to gather anonymous data through email. It works best when you start with open-ended instructions. Here are two that I use, depending on the project:

![]() List the 10 things you would do differently if we repeated this project.

List the 10 things you would do differently if we repeated this project.

![]() List the 10 things you would do the same way if we repeated this project.

List the 10 things you would do the same way if we repeated this project.

TOOL 10.5

Simple Survey

TOOL 10.6

Emotion-Based Survey Items

1. Describe the problems experienced on the project by entering on this line the emotion you felt: _______

2. Rank the intensity of that emotion (1 = low, 10 = high): _______

3. What factors contributed to your feelings about the problems?

4. Describe the successes experienced on the project by entering on this line the emotion you felt: _______

5. Rank the intensity of that emotion (1 = low, 10 = high): _______

6. What factors contributed to your feelings about the successes?

Tool 10.7 describes the nominal group process using email. The technique also can be used in a group setting if the facilitator enforces strict rules for participation. Specifically, all participants must respond clockwise from the facilitator, and must speak for a defined period of time (for example, five minutes). No one else may talk during another person's time.

TOOL 10.7

Nominal Group Technique Using Email

To make this process easier to understand, we'll use an example. Let's say you're doing a review of a project on which there was an issue with the initial task estimate. Here are the steps you follow to use email with the nominal group technique:

1. Email all the stakeholders the following message, being careful to phrase the controversial project issue in neutral terms: “We will be using an email facilitation technique to share our thoughts around the initial task estimate. Please rate the impact of this issue by responding with a number between 1 (low impact) and 6 (high impact). Email me your choice by [insert date]. Your response will be kept completely anonymous.”

2. Tally the responses you receive and report the outcome to each participant with this email: “Thanks for your participation. Here are the results of my initial data gathering: the average response was 3.5, the highest response was 5, and the lowest response was 2. I would like you to participate in a second round by sharing with me your rating (you may change it or keep it the same), and three reasons why you chose that number. If you are contributing for the first time, simply let me know your rating (1 = low impact; 6 = high impact) for this issue and give me your three reasons for your choice.”

3. Again tally the choices and summarize the reasons respondents submit. Send the tally and summary back to each individual.

4. Continue this process until you have consensus (which will probably not occur over email) or you can see that two definitive alternatives are polarizing participants. Bring people together physically to discuss the final two alternatives and move to consensus.

Warning: If you do too many iterations of this technique, the results tend to polarize. Try to stop before it has become too obvious to people that lines are being drawn.

Communication

As early as possible in the project, remind stakeholders that you'll be inviting them to take part in a post-project review after the completion of the project. This will help them think as they go and notice project issues, constraints, successes, and lessons they can share with others later.

The lessons learned need to be summarized and captured. Revisit your initial communication plan and send the summarized lessons to the same list of stakeholders. The sponsor needs a very macro-level look at the results, whereas the project team members need a more detailed summary of the lessons so they can make the most of them in subsequent projects. At a minimum, remember to make sure that all participants receive summarized lessons. There's nothing worse than investing your time in one of these reviews and then never hearing anything from it after the fact.

What If I Skip This Step?

Most people skip the post-project review—and that may explain why most companies are struggling more than ever with their projects. If you don't learn from your mistakes, you're destined to repeat them. You alone choose whether to prioritize the time to learn. Even if no one else wants to do the project review with you, there is tremendous value in taking as much time as you can squeeze out of your day to think through the project and harvest lessons for subsequent work.

Lurking Landmine

![]() Nobody wants to come to your review meeting or complete your survey. There's a lot of resistance to reviews because many people fear that the meetings turn into blame sessions. Try to find a way that's less time consuming and completely safe to encourage people's participation. Even if you can get them to send you only a simple email with “what went well, what didn't go so well,” you'll learn something. Ask for their help—people generally like to respond to that. Ask more than once so they know it's important to you.

Nobody wants to come to your review meeting or complete your survey. There's a lot of resistance to reviews because many people fear that the meetings turn into blame sessions. Try to find a way that's less time consuming and completely safe to encourage people's participation. Even if you can get them to send you only a simple email with “what went well, what didn't go so well,” you'll learn something. Ask for their help—people generally like to respond to that. Ask more than once so they know it's important to you.

Step 10 Checklist

![]() Remind people during the project that there will be a post-project review approximately three months after project completion.

Remind people during the project that there will be a post-project review approximately three months after project completion.

![]() Document the lessons learned and share them with others.

Document the lessons learned and share them with others.