STEP SEVEN

Adjust Your Schedule

OVERVIEW

Contemplation—the Zen of Project Management

The Project Schedule as a Tracking Device

Sponsor-Level Decisions

Ten Warning Signs of Trouble on the Project

Once the project starts, the phone will ring. There will be news about the project that will seriously affect your project schedule. In this step, you'll learn how to adapt to these changes while minimizing stress.

Years ago, my company contracted with a large firm to create training on the processes required to run a new manufacturing facility. The decision had been made to build this facility, staff it, and open it in two months, no matter what. We were asked to propose enough resources to get the training developed in three weeks and delivered in two more. More than 100 people would be trained in 10 different types of jobs. The client agreed during the Define phase that the #1 constraint for this project was speed (time), the second priority was quality, and the third was cost. The sponsor was willing to pay whatever it took to get this facility up and operating in the time given. This was one of the largest projects we'd ever done, and we were excited about it.

The contract was signed but, surprisingly, it took a couple weeks. Our five-week project began later than we had hoped. The training course developers tried to contact the client to set up interviews with the firm's subject-matter experts and to get copies of the job processes to be taught. After many attempts to contact the subject-matter experts and the project manager failed, we finally got a return call a week later. Process documentation was sent to us, but it was neither complete nor final. The subject-matter experts were too busy to meet with our training people until three weeks later, and then the project manager would be on vacation the week the experts were available. It was starting to look like this was not a time-constrained project after all.

Startled

and foggy-headed, Goldy patted the ground around him when his cell phone rang at midnight.

“Goldy?” said a quiet voice on the phone. “It's me, the BB. I heard that you and the boys were making houses to keep me out. I just wanted to give you an update on my plans.”

Now Goldy was wide awake. And he knew exactly where he was—inside a box made of hay, cardboard, and trash scraps. He really never thought the wolf would come back, at least not so quickly.

“Uh, uh, that's mighty polite of you,” he said. And he sat up so straight that his tipsy roof collapsed on his head.

“Well, I'm a polite kind of wolf,” said the caller. “So, here's the thing…. I'm standing outside your house, I think—although the roof here just fell in, so maybe I'm not at the right place. Anyhow, I'm getting ready to huff and to puff. Then, I'm off to Speedy's to see what I can get done over there tonight. My stomach's starting to rumble, and ham sounds good.”

Goldy hadn't squirmed more than five feet from the back side of his straw house before the hay was huffed and puffed away. He ran past the giant oak toward Speedy's house.

Speedy was sitting up, playing one tune and then another, when Goldy flew through the door. Some sticks broke away as he yanked it shut behind him.

“It's the wolf! It's the wolf!” he squealed. “He just blew down my house and he's coming this way. Are you sure these sticks will hold?” And a few more twigs fell out.

“Sure they'll hold,” said Speedy. “You worry too much. Look, these sticks are sturdy enough to make beautiful musical instruments, so they sure can stand up to one raggedy wolf. Catch your breath and listen to my music for a minute.”

Goldy didn't feel all that secure in his brother's house, but it looked much tighter and sturdier than what he had built. He guessed Speedy had spent a lot of time on it. Goldy'd been cheap—he hadn't had the money to build a place the way he wanted, and now he wished he'd worked with his brother instead of wasting time on his straw house. He felt like such a failure.

It wasn't long before the little pigs heard something not at all musical—a sound like a mighty wind. Little sticks, then big sticks began to fly around inside the house. The brothers, wide-eyed and frightened, crashed through the back wall just before it and all the other sides of the house blew across the clearing.

As they ran through the dark toward Demmy's house, the little pigs could hear BB whistling some music of his own.

In his neck of the clearing, Demmy was carefully securing his wagon-roof with the last of his bricks. He was exhausted, and it suddenly seemed he felt a chill in the air. Demmy slipped inside his cozy house and immediately fell sleep.

The constraints of the project obviously differed from those expressed by the client during the Define phase. If this truly was a time-constrained project, the firm's experts would be available to us and the project manager would not have been planning a vacation. The fact that the processes were incomplete and hadn't received final approval this late in the game was another warning sign. Al-though the opening date hadn't changed, every behavior we en-countered suggested that time was not a priority.

As our course developers struggled to build materials without clearly knowing the client requirements, more conflicting clues emerged. The subject-matter experts reviewed our draft course materials and sent them back, saying that the topics needed to be taught in a different order or the underlying job process had changed again. Pilot courses were scheduled, but then cancelled. Two weeks before the facility was scheduled to open, we were notified that getting the new facility running was postponed indefinitely and the training would not be needed.

We were paid for most of the work that we did. When the con-tract was signed, I suspect the client may have thought that the facility might never open, but there'd been no official notification. Every-one acted with blinders, including us. Suspicious that changes were coming, we all found it easier to go forward with the plan, even though the plan made less sense every day. It was a great learning experience, but painful. It was nobody's fault—everyone tried to do the best they could with what they knew. Signs of serious trouble were all around us—and no one took a hard look. If we had, we'd have challenged the project manager and thereby avoided a lot of fruitless work on our part and a lot of wasted money on the client side.

In this step, you'll learn how to look for the signs of trouble and react appropriately before it's too late. We're now entering the Manage phase of project management, and in this step you'll learn the zen of project management. You'll learn to respect and listen to the little voice in your head that warns you about trouble before you see the actual proof.

In Step 4 you learned a couple of ways to gauge the risk of a project. Using the quick-and-dirty risk assessment, you rated the project risk based on project size, requirements stability, and technology. You learned that you can use the average of these three numbers to choose the amount of time you'll spend practicing the zen of project management.

You probably were asked to lead a project because you had shown real talent at completing projects. For example, gifted programmers who have shown an ability to deliver code on time ultimately will earn a chance to lead other programmers toward the same end. The down-side is that the two different roles require very different skill sets, and “doing” aptitude is not the same as “managing” aptitude. When under stress, a project manager who's been great at “doing” will tend to go back to that same behavior to rescue the project instead of finding ways to engage the entire team. Project management is replaced by project doing—and the doing keeps the manager so busy that she or he no longer hears the inner voice pointing out warning signals.

Even if the project manager stays focused on managing, there's a lot to do: organizing and directing resources, controlling communication, and responding to revised requirements and other changes. A less active or less frantic practice, however, is frequently allocating time to think. Having this discipline forces the project manager to be more strategic about the project, looking at the future rather than just the problem of the moment. In Step 4 (tool 4.2) you learned how to determine how much project time you should invest in project management efforts based on the quick-and-dirty risk assessment. Now think about how much time you should set aside regularly for monitoring, contemplating, and listening to your inner voice—that is, how much time should be zen time. Tool 7.1 roughly estimates that time, based again on the project's risk level.

TOOL 7.1

Time Spent Monitoring, Contemplating, and Listening to Your Inner Voice—Zen Time

| Quick-and-Dirty Overall Risk Score | Zen Time |

| 1-2 | 15 minutes once a week |

| 3-5 | 1 hour once a week |

| 6-7 | 45 minutes twice a week |

| 8-9 | 30 minutes on each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday |

| 10 | 1 hour each morning, in company with the project sponsor |

Notice that the greater the risk, the more time you must hold and protect to think about your project. And, of course, it's the higher-risk projects that leave you no extra time, so it will be extremely difficult to practice this contemplative discipline. No matter how difficult it is, I promise you it's the best insurance against project failure that you can get.

I've found it easier to dedicate a specific time each week to thinking about all my projects. I use Friday mornings as often as possible to review each project, update the project spreadsheets, and send status reports to my stakeholders.

Time to Complete This Step

Step 7 is about monitoring your project from the time the first task in the project schedule begins until the sponsor says the project is officially complete. The time you, as project manager, will spend on this step is proportional to the risk of the project. The higher the risk, the more time you'll want to reserve for listening to your instincts and taking corrective action.

Stakeholders

The stakeholders possess the clues to the real, current state of the business need that the project is funded to serve. The closer you stay to your stakeholders, the clearer the true environment will be. The stronger the trust, the more you and your stakeholders will be able to manage uncertainty with honesty, even though neither of you will want to face reality. The trust you established during the Define and Plan phases (Steps 1 through 6) will help you do a great job working through the Manage phase. Here are two ways that good project monitoring improves your relationships with your stakeholders:

1. Keeping close track of the project and regularly communicating project status helps you manage stakeholders' expectations by letting them know what you're working on, what you need to get it done, and how it contributes to the success of the project.

2. Checking in with stakeholders occasionally as they complete project tasks to see how you can help builds their trust in you. It encourages them and helps you earn their respect.

It's critical to remember once again who owns the project. The sponsor, who is funding the project, owns the business decisions and the project. All changes to the business objectives, scope, project objectives, and constraints must be approved by the project sponsors. You, as project manager, prompt and facilitate the discussions needed to determine and support these changes when challenges come up because you're often the first person to notice that things are not going as planned. It's the sponsor, though—not the project manager—who has the final decisions to make. For example, if you figure out that, because of new requirements, the project is going to need either to be delivered two months later or to be reduced in scope, you would share your recommendation with the project sponsor, but he or she would ultimately choose.

TOOL 7.2

Questions to Ask Yourself at This Stage of the Project

1. What is the status of the project? Which tasks have struggled? Why? Which tasks have been completed with no problems? Why?

2. What are the critical deliverables that are holding up progress on the project? Who owns them? Why are they delayed?

3. What decisions made during the past seven days concern you, even just a little? What is it about the decisions that have triggered this concern?

4. What did you overhear through informal channels that rang warning bells for you?

5. Who haven't you talked to in a long time? Why have they gone silent?

Questions to Ask

The zen of project management is a term I use to describe the power of contemplation that all good project managers use. Based on your history with projects, you know a warning sign when you see it. Unfortunately, we often are too busy to listen to that inner voice and to adjust accordingly. To make time to correct this, at least once a week find a quiet place where you can sit down with the project schedule and answer the questions in tool 7.2.

When you give yourself time to focus, you let your inner voice move to a conscious level. In our hurried multitasking, it's normal to push the nagging inner voice away. There's certainly no time for bad news! But, as one of our customers likes to say, “Bad news early is good news.” Most executive sponsors don't like bad news about their projects, but they'd rather hear it while they can still do something about it. As project manager, the earlier you can react to a change, the more options you have available to you for moving forward successfully.?

Project Manager's Toolkit: Monitoring and Managing

In this section you'll learn techniques for figuring out when it's time to adjust your project definition and schedule. Many projects flounder because changes aren't made to the project schedule, rendering it unusable. It's important to note that if the business objectives, project objectives, scope, risk, or constraints change, the project definition will have to change as well. Once the impact of the change is understood, you'll apply a thought process you'll learn in this step to analyze your choices for moving forward.

Using the Project Schedule to Track the Project

In Step 6 you learned how to create critical path and Gantt diagrams to create a project schedule. At the outset, these diagrams show your best guess on how the project will go—and, in truth, the project never will go exactly that way. Once the first task be-gins, you use these diagrams to give you a visual model to monitor the status of the project. The critical path diagram is useful for adjusting your task dependencies and seeing how the changes affect the critical path, which predicts the project's completion date. The Gantt diagram can show you how the elapsed time on the clock or calendar will be affected by changes, including the scheduling of people working on the tasks.

Although it's tempting, when you're pressed for time, to skip the updates or just throw some additional tasks on it without really thinking of their effect, that's a temptation you must avoid. A well-maintained schedule is absolutely necessary. Updating your critical path diagram, your Gantt chart, or even your tracking spreadsheet (on smaller projects) shows you the downstream effects of upstream changes. Use the questions in Tool 7.3 when you're changing the project schedule to ensure that the change hasn't messed up some-thing else.

If you're using project management software on larger projects, you'll be able to enter actual task duration while keeping the planned task duration for historical purposes. The software will let you visit your planned view and your actual view at the end of the project so you can learn from the gap.

TOOL 7.3

Questions to Ask When Revising the Schedule Diagrams

1. Which tasks depend on others, and thus can't be started any earlier?

2. Which tasks depend on the same resources, and thus can't be done at the same time?

3. Which stakeholders will be most affected by these changes?

4. How will I communicate quickly and effectively with the affected stakeholders?

5. What will be the impact on the milestones (dates)?

6. What will be the impact on the people working on the project? As the tasks are pushed farther out on the calendar, will key resources still be available?

As mentioned in Step 6, adding actual duration to tasks can change the tasks that are on the critical path and the slack time for other paths. The software recalculates the dates based on the actual task duration as soon as that's entered. It's not unusual for a delayed task to cause the critical path to change. In other words, the path on which a delayed task is positioned has now become the longest path—and that makes it the critical path.

POINTER

Information Updating Options

It requires discipline and time to keep the project schedule up-to-date with project management software. To collect and update actual task durations on a large project can be a full-time job. It's a good idea to have someone play the role of project librarian or administrator, responsible for keeping all the documentation current and for handling status communications. If your project isn't large enough to need this kind of detail, consider using the spreadsheet approach.?

Maintaining the critical path diagram as changes occur will help you keep a steady focus on the most critical tasks. A good project manager knows to keep one eye on the critical path while monitoring the other paths—at any moment, the path that is critical may change.

Emailing the Tracking Spreadsheet

You learned about the project tracking spreadsheet in Step 6. On small to medium-size projects, the critical path diagram may not be as important to maintain, and the tracking spreadsheet may be enough. When there are fewer people working on the project, there are fewer parallel task paths to monitor. The project tracking spreadsheet manages the project from a due-date perspective rather than a task-completion perspective. In other words, a row in the spreadsheet may show you that the task has to be done by the first of next month; the duration is really irrelevant.

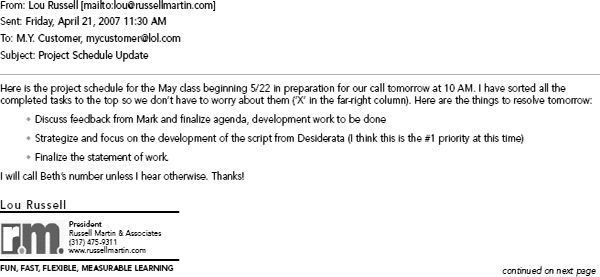

The tracking spreadsheet is a vital tool for managing expectations with your stakeholders. As tracks completed, you'll update L the start of the project, send the updated version of the spreadsheet to your stakeholders on a regular basis, ideally at the same time each week. Create a pattern of regular communication. Example 7.1 is a sample email that includes a current spreadsheet in the body of the email.

When you update your spreadsheet, color-code the rows and include the explanatory legend in each email. I like to use red for late tasks, blue for tasks that are in progress, strikethroughs for tasks that we've agreed to delete from the plan, and black for tasks. that are pending. Color adds a level of instant comprehension when the legend is understood. I indicate completed items with an “X” in the Done column so they can be sorted to the top. Including the completed tasks is important to show progress so everyone feels part of the success.

POINTER

Tips for the Project Spreadsheet

When using a spreadsheet to monitor the plan, and managing to a due date rather than a task, it's very easy to overestimate how much work can be done by a specific date. Keep an eye on your resources, especially those who are working on other things at the same time. Whenever possible, under-promise and over-deliver.

EXAMPLE 7.1

Sample Project Update Email

Managing Issues When They Arise

In Step 4 you learned to identify, analyze, and plan for risk. Once a project starts, issues arise. The difference between a risk and an is-sue is that a risk is an anticipated possibility, but an issue really has happened. Some issue will affect a task, the project schedule, and/or the budget. You'll need to identify and address the issue in a creative way, and that will minimally affect the project's forward progress.

When an issue arises, your first instinct as manager is to react quickly—to jump to solving the problem immediately. Reacting quickly to an issue without thinking about all of the ramifications can cause more problems than the issue itself. It's better to use the guidelines in Tool 7.4 and think through the issue in detail before you move forward.

Checking the Warning Signs

There are very clear warning signs when a project's priorities are changing. Tool 7.5 has a complete list of questions you can ask yourself to help you see these signs, and below we'll look at the signs in detail.

Warning Sign 1: Faces Are Missing

Not seeing your project sponsors face to face or not communicating with them in some two-way fashion over more than a week is one of the most telling signs of trouble. If your project sponsors don't hear from you on a regular basis, they'll assume the worst. You may feel relieved if you don't hear from your project sponsor regularly, but you also may be losing your sponsor to a new job or a new company. If face-to-face interactions are too difficult to schedule, a less personal form of communication (like email) in both directions must be regular and predictable in its timing.

TOOL 7.4

Guidelines for Dealing with Issues

![]() Analyze the problem causing the issue. Move past the symptoms to the real causes. Don't jump to a solution before you understand the issue.

Analyze the problem causing the issue. Move past the symptoms to the real causes. Don't jump to a solution before you understand the issue.

![]() Determine the impact on the project. Which of these elements does the issue affect: business objectives, project objectives, scope, risk, constraints, resources, schedule, budget, or some other aspect?

Determine the impact on the project. Which of these elements does the issue affect: business objectives, project objectives, scope, risk, constraints, resources, schedule, budget, or some other aspect?

![]() Decide who owns the issue so you can identify who needs to be involved in the solution. Make the following determinations:

Decide who owns the issue so you can identify who needs to be involved in the solution. Make the following determinations:

![]() Who has the decision-making authority to act on the issue?

Who has the decision-making authority to act on the issue?

![]() Does this person know the decision belongs to her or him?

Does this person know the decision belongs to her or him?

![]() When should the issue be brought to higher-level attention (escalated)?

When should the issue be brought to higher-level attention (escalated)?

![]() Is moving the issue up the line a positive thing?

Is moving the issue up the line a positive thing?

![]() Is the escalation path clearly defined?

Is the escalation path clearly defined?

![]() Identify potential solutions when escalating an issue.

Identify potential solutions when escalating an issue.

![]() Involve project sponsors when needed.

Involve project sponsors when needed.

As part of your communication plan, make sure that high-level and factual project status reports are getting to your sponsor(s) each week.

Warning Sign 2: Status Meetings Become “Who Hunts”

You're getting a leading indicator that it's time to step into team dynamics when project status meetings become Who Hunts—ineffective gatherings where time is spent trying to blame someone in-stead of moving forward to a solution.

When your status meetings are eaten up by ineffective blame games, you have a team that's confused about direction and roles. Lead people through a discussion about the problems they have. Let people express themselves honestly, then help them work through the conflict so they can perform effectively again. An effective project meeting drives project success. Ineffective meetings burn project hours with no benefit.

TOOL 7.5

Questions to Ask When You Go Looking for Trouble

1. How often are you meeting with sponsors? (warning sign #1)

2. How effective are your project status meetings? (warning sign #2)

3. How accurate have the task estimates been so far? (warning sign #3)

4. Are there key sponsors who may be leaving? (warning sign #4)

5. How often does the core project team meet? (warning sign #5)

6. Are the team and stakeholders still engaged? (warning sign #6)

7. Are there new project risk factors being discovered? When was the last risk assessment performed? (warning sign #7)

8. Has the scope of the project changed? (warning sign #8)

9. Are any key stakeholders leaving the project? (warning sign #9)

10. How healthy are the team members? (warning sign #10)

Additional questions to think about include

![]() Is the project documentation up-to-date?

Is the project documentation up-to-date?

![]() Are there regular communications with all the stakeholders?

Are there regular communications with all the stakeholders?

![]() What are your instincts telling you about the current state of the project?

What are your instincts telling you about the current state of the project?

Warning Sign 3: An Early Task Is Greatly Underestimated

If one of the early tasks on your project schedule takes several times as long as you had estimated, there are two ways you can view the delay. You can write it off as an understandable ramping-up fluke and just resolve to make up the time on later tasks, or you can consider this a serious sign of ultimate danger and make massive changes to your project schedule.

POINTER

Email Tip

Including the spreadsheet in the body of the email rather than as an attached file keeps the stakeholders from doing their own updating and sending their version of the spreadsheet back to you. If every stakeholder can make alterations, you'll chew up a lot of valuable time trying to get the different views back together. If you cut and paste the spreadsheet into the body of the email, people will be forced to send you an email update explaining their changes. This lets you compile all the requested revisions and resolve conflicting changes from multiple stakeholders. If, instead, everyone updated the same spreadsheet and sent it back to you, some changes surely would be lost.

If the obvious choice to you is to catch up later, know this: that choice is insane. A task coming in late at the beginning is the leading edge of a trend, not a fluke. The right choice is to look at the project schedule and figure out what you'd do if all the tasks took three times as long as you've estimated. Gulp. Take this sign as a gift and adjust your schedule now, before it's too late.

Warning Sign 4: Email Recipients Change

Keep an eye on formal emails. When you start noticing changes in who is copied on project emails, red lights should go on all around you. On one of my recent projects I noticed that suddenly my project sponsors were no longer copying the company president on project status documentation. He left the company shortly thereafter.

Warning Sign 5: There Is No Time for Status Meetings

It's a signal if you get too busy with other duties to hold a status meeting or people stop showing up for meetings. There could be several causes. Maybe people on the team believe they're fully aligned and don't need to spend time talking. This is a great feeling of a healthy team, but can create a surprising negative side effect. Any team that doesn't talk eventually will find itself misaligned. When things are going well, keep the meetings brief and to the point. Standing appointments work well for early meetings.?

It's also possible that the project is starting to tank and every-one's afraid to talk about it. Of course, this is the exact time when a project status meeting is critical. Do whatever you must to get the right people in the meetings.

A third possibility is that the meetings have become tedious. The same people speak, and the same topics are covered over and over again. Get some help from your HR organization or local consultants to make your meetings productive again—create some new facilitation techniques, help people listen more effectively, and de-sign more effective ways to resolve and track issues. Sometimes a little change is all participants need to be attentive again.

Warning Sign 6: The Silence Is Deafening

It's a bad sign when you stop hearing from people. Track how many project-related emails you get every day. This number should never go down—only up. Email quantity decreasing might indicate that the project is no longer a business priority and is about to be cancelled.

Warning Sign 7: Risk Factors Appear to Have Changed

If you're taking advantage of your contemplative zen time, your inner voice will tell you when a new risk appears. Be aware of what you ob-serve and hear all around you, and let your intuition speak. If you believe something is posing an unanticipated risk to the success of the project, bring it up at a private or group meeting with your sponsors or stakeholders. Don't ignore it until it's too late to mitigate.

Warning Sign 8: Scope Has Changed

If one of the subject-matter experts or sponsors says to you, “It's only a little change; thanks for doing me this favor,” and you make the change, you're in trouble. A task cloaked as a favor can kill your project because it sets a dangerous precedent that it's OK to ignore the project schedule and expand the scope. Be vigilant and help your team be vigilant against sneak attacks. Scope change must be handled the same way each time. Everyone has to know it's there and agree to it, and then resources have to be adjusted accordingly.?

Warning Sign 9: Some Team Member Is Really Dressed Up

There's an interview in that person's immediate future. It doesn't have to be the sponsor to have serious repercussions on the project. It can be any critical member of your project team. Talk privately with this person to see what you can do to keep her or him.

Warning Sign 10: People Are Getting Sick

If you're noticing an uptick in sick time, late arrivals, early departures, doctor's appointments, or other reasons people use for avoiding tasks or meetings, pay attention early. This is an indicator of a stressed project team. Stressed teams don't complete tasks effectively. Invest time in figuring out with your team how to improve their work environment, or the project quality will suffer. More important, people's lives will suffer.

Adjusting Your Project

Your project will struggle at some point and may struggle the entire way. As manager, you must make strategic choices to get the project back on track. If you wait for problems to be fixed magically on their own, your project will fail. You must acknowledge and address change, or choices will be made for you.

In Step 2 you documented the starting constraints of the project. When the project begins to struggle, it's a good idea to revisit the constraints with all the sponsors to see if anything has changed that will reorder the constraint priorities. If the #1 constraint is still the top priority, you won't be able to negotiate any more of it. Instead, negotiate the #2 or #3 constraint with the sponsor.

Any project may be plagued by one or more of these conditions:

1. It may be behind schedule.

2. It may be over budget.

3. It may be producing output of insufficient quality.

4. The scope may have increased without a corresponding increase in schedule or budget.

The solutions to those problems could be

1. increase the time

2. increase the budget

3. decrease the quality requirements

4. decrease the scope.

Let's take a closer look at those four solution options, starting with increasing the time. When companies establish dates for project completion, those dates may or may not be fixed in stone. There's an interesting dance that occurs in business: Sponsors may ask for very ambitious dates because they know the projects are always de-livered late. If you need to ask for more time, the time to ask for it is not a week before the project is due. Ask as early as possible.

Perhaps a bigger budget is possible. Sometimes you can hire consultants or add staff when a project is under resourced. In general, however, adding people to a project that's already in trouble will increase your trouble. Having more people on a project team requires more communication. In his book The Mythical Man-Month, Frederick Brooks explains that some tasks can't be subdivided easily—for example, you can't hire nine women to have a baby in one month.

A third option might be to work faster and for more hours and to eliminate less-essential tasks. This is what novice project managers try to do under stress. This strategy usually risks the project quality. Working as hard as you can is not sustainable (remember Warning Sign 10). In addition, it's often true that the less-essential tasks that are skipped are related to audit and control activities or simply are things the project team doesn't enjoy. Skipping tasks like “testing” will result in poor output quality.

As a fourth option, you can decrease project scope by doing a smaller subset of the total project with the available time and budget. This is actually the sanest approach. If you can narrow the scope of a project, and deliver a smaller but still full-quality project on time, you can deliver the rest in subsequent releases. This is a common approach, but it only works if the scope was clear and shared at the very start of the project. Some project managers, however, use this approach as a crutch for poor estimating, and sponsors get pretty sick of hearing about releases after a while.

Pushing the Decision to the Sponsor

It's hard but important to remember that the project belongs to the sponsor, the person with the business need and the money. The project manager is the steward of the project, watching it, nurturing it, and taking care of it until it's completed. The planning, organizing, and controlling of the project belong to the project manager. Unfortunately, project managers also make decisions every day about the future of their projects—decisions that should be made by the sponsor.

Project sponsorship requires establishing the business case for the project and then making the choice to invest, based on analysis of the return on that investment. Good sponsorship is not practiced enough in most companies, so it falls to the project manager to help the sponsor understand the imperatives of the role. More important, when project constraints or scope change, the manager must push choices with investment ramifications back to the person who owns them—the sponsor.

Let's say a project is running out of time and likely not to meet the deadline. The project manager has the options you read about above: deliver late (and likely over the budget), buy some help, de-liver poor quality, or reduce the scope. Project management beginners make that decision on their own or with their team, but it's a decision that belongs to the sponsor. In many cases, here's what happens: The sponsor (or someone from her or his organization) re-quests that the manager increase the scope of the project, based on a change in the market. The sponsor, however, doesn't tell the project manager about the business market change. The project manager first grumbles and complains about how the sponsor is always changing her or his mind, and then sets off to increase the scope by stealing time from other project tasks, buying more resources, or neglecting quality.?

As project manager, don't lose your sense of identity in the project—or your commitment to your appropriate responsibilities. And remember that the project belongs to someone else; it's simply on loan to you.

Communication

Figure 7.1 illustrates the findings of research done with IT projects. The results indicated that project managers who lie about their project status are likely to bring their projects in extremely late and over budget, if at all (on average 100 percent over budget). Project managers who tell the truth tend to bring the project in on time (if they keep their jobs). Why? Because telling the truth gets you the help you need before it's too late. Unfortunately, no one likes to deliver bad news upward, so the tendency to stretch the truth is very prevalent. Depending on corporate culture and politics, it may be necessary for you to pass project information to some other person who then will share it with the corporate sponsors. In that case, be sure to craft your communication in a clear and easily presentable form so that all the other person has to do is deliver the message. If your message isn't explicit and easy to grasp, you run the risk of playing project management “telephone,” with your intermediary rephrasing and possibly misinterpreting what you're trying to say to your sponsors. If your news isn't good, there's a strong risk that the person you're depending on to deliver your project status report will join “The Liars Club” and minimize the bad news. Make sure your relationship with the intermediary helps him or her tell the truth.

Communicate early and often. I recently worked with a company that had aligned most of its resources with three critical and very large projects. The people on those project teams obviously had their hands full, especially with the political pressure on them. However, as I talked with people who were not involved with the critical projects, I learned they felt very left out. They were finding it impossible to secure the resources needed to get their own work done, and resources they thought they had often were swung over? to the big projects with little or no prior notice. When I asked them how the big projects were going, and what they could do to help them be successful, they stared at me with blank looks on their faces. “Nobody tells us anything,” they said.

FIGURE 7.1

Research Results: The Liars Club

The gray line indicates a typical “lying” project-one in which the real project status was not shared until it was too late. The black line indicates a typical “truth” projects—one in which the real project status was shared early and often (and, early on, the project was late), but the truth provoked the focus that the project team needed to proceed successfully.

Source: http://web.mit.edu/jsterman/www/Liar%27s_club.html.

It was an interesting learning experience for me. The success of the three mission-critical projects also depended on the individuals and teams who kept the operational side of the business going while the big projects were completed. They were stakeholders, but weren't being treated as such. No one thought of communicating with these people because they weren't directly associated with the project. The lesson for all project managers is to think of the public relations component when you're communicating project status. Think beyond those people who touch your project directly; remember the people whose buy-in may affect your project. How can you keep them enthusiastic and rooting for your success?

This is the point in the project when all the investment you have made in documenting the project will pay off. As change occurs—and it will—you'll have the information necessary to negotiate appropriate interventions. The deliverables themselves may change because they're artifacts of the life of the project. These deliverables include Each time one of these deliverables changes, communication must occur. The further into the project you are, the more updating and communication is necessary. For example, a change that affects the schedule most likely also affects the project objectives and scope.

1. the Define deliverables (Steps 1–5)—objectives, scope, risks, and constraints

2. the project schedule (Step 6)—the tasks, milestones, dependencies, and resource allocations

3. the key roles of project sponsor and subject-matter expert.

What If I Skip This Step?

It would be nice—but impossible—to skip change. Making choices and implementing contingency plans will be done either by the project manager, or by neglect and default. A good manager owns these choices. He or she knows how to take the time to contemplate the project and think strategically, not just tactically. The warning signs are watched for and addressed. The project sponsor makes the business decisions, not the project manager. These are all critical behaviors for a project manager, and if change is ignored, the project will fail.

Lurking Landmines

![]() The sponsor doesn't want to make any decisions and pushes everything to you. First, be careful which decisions you push to the sponsor. The choices sent upward often are either too detailed or too broad. The sponsor should not be making decisions about detailed project tasks. Keep the sponsor's focus on the project's return-on-investment. When problems arise, use your expertise to bring the sponsor your recommendations for solutions to the problem, but let the decision be made by the sponsor.

The sponsor doesn't want to make any decisions and pushes everything to you. First, be careful which decisions you push to the sponsor. The choices sent upward often are either too detailed or too broad. The sponsor should not be making decisions about detailed project tasks. Keep the sponsor's focus on the project's return-on-investment. When problems arise, use your expertise to bring the sponsor your recommendations for solutions to the problem, but let the decision be made by the sponsor.

![]() Something is unsettling, and you don't know what it is. If you have a funny feeling about a project, it could be that inner voice. You can't hear the inner voice unless you stop long enough to listen and cut out the surrounding noise enough to hear. Practice the discipline of giving yourself the time, as frequently as risk dictates, to answer the question, Do I know where my project is?

Something is unsettling, and you don't know what it is. If you have a funny feeling about a project, it could be that inner voice. You can't hear the inner voice unless you stop long enough to listen and cut out the surrounding noise enough to hear. Practice the discipline of giving yourself the time, as frequently as risk dictates, to answer the question, Do I know where my project is?

Step 7 Checklist

![]() Watch for the warning signs of pending project disaster.

Watch for the warning signs of pending project disaster.

![]() Give yourself time to think about your project.

Give yourself time to think about your project.

![]() Adjust your project, using the levers of time, money, quality, and scope.

Adjust your project, using the levers of time, money, quality, and scope.

![]() Push changes that affect the return-on-investment back to the rightful owner—the sponsor.

Push changes that affect the return-on-investment back to the rightful owner—the sponsor.

The Next Step

The next step will be about managing the people issues that can derail your project. In project management, it's always the people, so adapting to different communication styles and negotiating and managing conflict are key to project success.