STEP FIVE

Collaborate Successfully

OVERVIEW

A Shared Vision for Your Project

Interaction with Diverse Personalities

Delegating and Coaching

Productive Project Meetings

My company worked on a large training roll-out for state agencies getting new software. As our project team developed the training, they often were irritated by the software developers' inability to get them the screens, reports, and basic application functionality that the training was supposed to teach. Each morning a different course developer would remark about what jerks the software people were. When classes began, the trainers often were furious to find that the programmers hadn't reset the test data or had changed another screen during class! Rarely did a day go by that someone wasn't mad at a software company staff member.

I'm guessing that the same conversations were happening at the software company. I can imagine its staff telling their managers what jerks were on the training team. I'm sure it irritated them that we continually were interrupting their work, making it even more difficult to finish the system. To them, it was much more important to complete the software development than to build training, especially because the software was what they were being paid to deliver.

With his fine stash

of new band instruments all ready to share with his brothers, Speedy turned toward his house. A few sticks lay at his feet and, when he tossed them onto the roof, it tipped at a shaky angle.

“Well, I'll get plenty of ventilation,” he thought. He'd pretty well convinced himself that the wolf was long gone, so he packed up his instruments and went to look for his brothers.

Dusk was falling as he clattered across the clearing. In the distance, he could just glimpse a figure struggling toward him, pulling a wagon.

“Demmy!” he shouted, and hurried ahead to help.

“Speedy, thank goodness you're here. I'm about to give out. Please give me a hand pulling these bricks into the clearing.”

Speedy stared at the wagon and couldn't think of anything he'd less like to do. “Demmy,” he pleaded, “forget this house business. I've found a way to make instruments out of sticks! We'll form a band and make so much money that we can pay the wolf off, if he ever comes back.”

Demmy was furious. “Speedy, this is serious. The wolf's probably watching us from the woods right now, just waiting for a good time to strike! Haven't you built any house at all?”

“Well, sure I have,” Speedy answered. “It's over there—the one made from sticks. Let's go there and get a good night's sleep, and we can talk more about this in the morning.”

Demmy shook his head and tugged on the wagon pull. With a shrug, Speedy went looking for Goldy.

He found that brother struggling with the last touches on his unstable structure—and in a nasty mood, too.

“Are you crazy?” Goldy screamed, as Speedy tried to tell him about the band. “I've finally finished this stupid house, and I'm over it! Just leave me alone. I'm going to sleep.” And he very carefully edged into his cardboard-topped cabin.

“Fiddle-dee-dee,” thought Speedy, “It'll all be better tomorrow.” Then he carried his sticks back across the clearing and went to bed.?

This interpersonal dynamic is so common on projects! There's always an us and a them. Whether it's the project team and the business sponsors, or the IT developers and the subject-matter experts, people naturally build alliances to protect themselves from other alliances. Business has a long tradition of encouraging competing tribes on project teams. It's so easy to slip into this dynamic. Add increasing stress to the situation as the project progresses, and you can have outright civil war.

In his book Selling the Dream, Guy Kawasaki talks about the value to a team of having a strategic enemy. Nothing unites a group of people faster than a common foe. Unfortunately, teams left to their own devices often will pick a completely inappropriate enemy and thus damage the velocity of the project. Stakeholders who turn on each other challenge a project timeline more than anything else that can happen.

A project's success comes from delivering the right solution to a business challenge or opportunity. One stakeholder can't be successful at the expense of another. In a project that develops new software applications and puts that software successfully into use, how can the software be implemented effectively without good training? How can good training occur without good software? Us against them is common, but it's selfish and mutually destructive. It helps no one.

The project manager owns the success or failure of the project, and, thus, is responsible for keeping all the stakeholders connected in a positive way. Adversarial relationships aren't built suddenly—they develop. Collaboration is the same—it's a moment-by-moment, individual decision. Each day, in a thousand different conversations, you'll be faced with the subtle decision to choose conflict or collaboration, as will every stakeholder. Many times you'll really want to pick conflict. The smart project managers, however, know that the way to win is to seek first to collaborate, no matter what.

Collaboration doesn't mean that there will be no conflict. Conflict is a good thing on projects, ensuring that teams are learning from each other and moving in the same direction. (You'll learn more about conflict and negotiating in Step 8.)

In this step, which is still part of the Define phase, you'll set the stage for practicing great project leadership. You'll state and communicate the vision of the project, coach and delegate effectively, treat each stakeholder in a way that is uniquely suitable, hold productive meetings, and practice being resilient in the face of change.

Time to Complete This Step

The act of collaborating takes only seconds at a time, but it must be practiced many times a day. The amount of time you'll spend leading is proportional to the project risk. Consider blocking time to think about collaboration at the same time each week. What things that have happened during the week have prompted feelings of anger? How has this anger been shutting down your communication? What can you do to build collaborative behavior instead?

Stakeholders

As project manager, try to get all the stakeholders and members of the project team together at the beginning of the project to talk about your project vision and how you will lead the project. Doing so will set a baseline for future discussions when conflict starts.

Questions to Ask

As leader of the project, answer the following:

1. How can I share my vision of the project with the stakeholders?

2. What leadership strengths and challenges do I bring to a project?

3. How can I delegate responsibilities and coach team members effectively?

4. How can I adapt my communication style to different team members so that I meet their unique needs?

5. How can I ensure that our project meetings are productive?

6. Knowing that the project will change frequently, how can I model and teach others the ability to recover from or adjust easily to change?

7. Have I said anything that might lead my staff to believe I support ongoing conflict?

8. Have I done anything that might lead my staff to believe I support ongoing conflict?

9. How can I help my team continually choose a problem-solving approach that promotes collaboration?

A leader must model the behavior he or she is asking of others. It's easy to get annoyed when the stakes are high and you're in charge, but the staff replicates the behavior of the leader, so you must stay mindful of how you're behaving all the time. When the leader screws up—and all leaders do—he or she quickly must fess up to the mistake and get behaviors back in synch with project success. Worksheet 5.1 is a brief assessment you can use to evaluate your strengths and challenges as a project leader.

The competencies that you rate as high are the behaviors you do well and are most comfortable doing. Other people most likely would describe your strengths in these terms. The competencies you rate as low are the behaviors that you struggle with. It's important to be aware of these, but it's highly unlikely that you could ever turn them into strengths. Instead, build a network of friends and staff who you can depend on to fill this gap for you. The competencies that you rate as medium can be vastly improved with a little learning (through training or mentoring) and practice. To validate the results of your self-assessment, you might want to ask a couple of your peers, your staff, and maybe your boss to tell you their opinions.

Project Manager's Toolkit: Create and Lead an Effective Team

As the project progresses, it becomes more and more of a challenge to continue to lead. In this section, you'll learn effective means of project leadership, including

![]() setting a project vision and getting others to buy into it

setting a project vision and getting others to buy into it

![]() delegating and coaching

delegating and coaching

![]() holding productive project meetings

holding productive project meetings

![]() building resilience among team members.

building resilience among team members.

WORKSHEET 5.1

Assessment of Your Project Leadership Abilities

Instructions: This assessment is intended to show you where your project leadership strengths lie and where you have room to improve. On each of the following abilities, honestly rate yourself high, medium, or low.

1. |

Build cohesive teams with shared purpose and high performance |

RATING: |

2. |

Set, communicate, and monitor milestones and objectives |

RATING: |

3. |

Gain and maintain buy-in from sponsors and customers |

RATING: |

4. |

Prioritize and allocate resources |

RATING: |

5. |

Manage multiple, potentially conflicting priorities |

RATING: |

6. |

Create and define systems and processes to translate vision into action |

RATING: |

7. |

Maintain an effective, interactive, and productive team culture |

RATING: |

8. |

Manage budget and project progress |

RATING: |

9. |

Gather and analyze appropriate input, and manage the “noise” of information overload |

RATING: |

10. |

Manage risk-versus-reward and return-on-investment equations |

RATING: |

11. |

Balance established standards with the need for exceptions in decision making |

RATING: |

12. |

Align decisions with business and organizational/team values |

RATING: |

13. |

Make timely decisions in alignment with customer and business pace |

RATING: |

Sources: Adapted from Lou Russell and Jeff Feldman, IT Leadership Alchemy (New York: Prentice Hall, 2003); and Lou Russell, Leadership Training (Alexandria, VA: ASTD Press, 2003).

Setting a Project Vision

For a long time, vision has been acknowledged as an essential quality of leadership. But vision is still something not entirely understood by everyone. Even when the trait is understood, the practice is rarely mastered. This section will address the dynamics of vision—how we understand it as a concept, how we create it, and how we apply it to inspire achievement in a fast-paced, challenging world.

Vision is a vividly imagined sense of a desired future. It's the destination we aim for, the outcome we want. Vision also is a path we travel in carrying out our project's purpose—not just a destiny, but the actual journey in pursuit of that destiny. Vision isn't an answer only in response to the questions, what do we want? or where are we going? It also answers the question, how do we get there? Although it may seem that knowledge of the destination must precede the choice of paths, that may not always be true. Certain destinations only become clear when the journey along a specific path has begun—thus the need to keep vision dynamic.

We might choose to think of vision as a story. There is great power in story as a medium for communicating a message. Story captures the imagination, conjures powerful images, and creates strong connections. Vision is the story we tell about our future, and as we tell and retell the story, it becomes familiar to us. We come to know how it unfolds and how it ends—and we become attached to that ending.

POINTER

Successful Projects Matter to People

Research by Michael Ayers looked at the causes of resistance to work and found that people resist work for five key reasons:

- The purpose of the project doesn't engage them.

- The project doesn't need them.

- The project seems impossible.

- The project isn't consistent with their personal values.

- They don't know what they're supposed to be doing.

Clear project communication, vision, and coaching help people deal with all five of these concerns.

An engaging vision is a key deliverable for a project manager because it offers the following advantages:

![]() It provides focus—In a world full of opportunity and distraction, a clear vision enables all parties to remain focused on the commitments we are making to ourselves, our customers, and other organizational business units. Constant attention to the vision keeps us on course and allows correction when things change.

It provides focus—In a world full of opportunity and distraction, a clear vision enables all parties to remain focused on the commitments we are making to ourselves, our customers, and other organizational business units. Constant attention to the vision keeps us on course and allows correction when things change.

![]() It provides inspiration—The inspiration it offers is what makes vision such a vital component of leadership. Leaders harness human potential and human energy toward a desired end, inspiring performance by getting people excited about their roles in the project.

It provides inspiration—The inspiration it offers is what makes vision such a vital component of leadership. Leaders harness human potential and human energy toward a desired end, inspiring performance by getting people excited about their roles in the project.

![]() It provides hope—As the demands for speed, results, and constant change grow ever stronger, it's easy to become frustrated and disillusioned. Vision provides a positive, forward-facing focus—a we-can-do-this” attitude.

It provides hope—As the demands for speed, results, and constant change grow ever stronger, it's easy to become frustrated and disillusioned. Vision provides a positive, forward-facing focus—a we-can-do-this” attitude.

The vision of a project remains steadfast, even in times of rapid change. In fact, the boundaries and guidelines framed by vision help us navigate such change successfully. The essence of vision remains constant, regardless of the pace of change.

Information gathered and generated by the following questions answered in Steps 1 through 4 of this book have set the stage for creating a vision for your project:

1. What is the ultimate outcome we want for this project?

2. What will each of us have to do in support of that outcome?

3. What is our timeframe?

4. How will we measure our success? Who will measure it?

5. What benchmarks will we set as a means of measuring our progress along the way?

6. What communication process will we use to keep all stakeholders aligned and informed of the vision as it unfolds?

Now it's time to write a vision statement. This is a simple process that can be done during a one-hour meeting. Here are the steps to follow:?

1. Ask each sponsor, stakeholder, and team member to write his or her own description of the project's vision, using three verbs and one noun. Be sure to be ready with several examples to get them started—but don't make them examples that pertain to the current project.

2. Make a list of all the verbs and a list of all the nouns used in the statements. You can do this by collecting everyone's work or by asking participants to call out the words while you write them on a flipchart.

3. Discuss the differences among the verbs and among the nouns, and come to an agreement on which one noun and which three verbs are most suited to the group's vision of the project.

4. Write a concise and meaningful vision statement from these words.

Do your best to energize stakeholders in this visioning effort. The more you can get them involved in writing the vision statement, the easier it will be to enroll them in the vision itself.

Example 5.1 uses our blog project to illustrate this process. Notice the difference in the three initial vision statements. Each one reflects the narrow perception of an individual. The blog project will create a blog, and if it's successful it will streamline product sales and enable the customer to communicate more effectively back to the company.

As project team members share their “local” views, it will become clear that there is an engaging, bigger-picture view that will require all of them to work together. A good vision gives you a reason to look forward to going to work. No one jumps out of bed in the morning saying, “Yeah! I can just get by today!”

It's common during this exercise for people in the first round to focus only on the project deliverables for which they're responsible, like technology or a new product, or new/more customers. Sometimes those narrow-focus deliverables are a means to an end—technology and products are obvious examples. Remember the importance of the business objective—increase revenue, avoid costs, and? improve service. The final vision focuses on customer communication, with the technology as an enabler. When you're writing your project vision, it's OK to break the one-noun rule to make the vision statement more clear, as long as you keep the main object of the sentence clear.

EXAMPLE 5.1

Creating the Blog Project Vision Statement

| 1. | The project manager received these three vision statements from project stakeholders: |

|

|

|

| 2. | The manager wrote the following lists on the whiteboard: |

| Verbs | Nouns | |

| design streamline | blog site | |

| implement initiate | product sales | |

| build demand | customer communication | |

| grow respond | ||

| enable |

| 3. | At the end of the discussion, the group agreed to the following vision statement for their project: The blog project will initiate, enable, and respond to customer communication through a web blog site. |

Enrolling Sponsors and Stakeholders in the Vision

If the sponsors participated in the vision exercise, that's wonderful. In most cases, there are stakeholders who either are not available or are too high up in the organization to have time for project team meetings. But that doesn't mean you just leave them out of the vision loop. Rather, once your visioning meeting has produced a vision statement that everyone attending the meeting has agreed to, it's time to communicate it to all the stakeholders (including those who didn't attend the meeting) to secure their buy-in.

TOOL 5.1

Questions to Help You Get Stakeholders to Buy Into the Vision

| 1. | What does this audience most want to hear? How can the vision statement appeal to, address, or satisfy that desire? |

| 2. | If your vision is presented in story form, rather than as a declarative statement of intention, how clearly will this audience identify themselves as vital characters in it? How can their character roles be clarified further and brought to life more fully? |

| 3. | In which aspects of the vision statement will this audience find inspiration? How can you maximize the inspirational quality? |

As you plan how you'll present the vision statement to people who haven't been involved in fashioning it, remember that knowing your audience means knowing what will inspire them, and using that knowledge to your advantage means packaging your message accordingly. Use the questions in tool 5.1 to prepare your presentation to your stakeholders.

Visions must be communicated early and often—once is not enough. A successful vision statement comes up in discussions about changes and challenges. You may inspire your stakeholders and get their commitment through your initial communication process, but carrying out the agreed vision can be a long and arduous endeavor, and initial enthusiasm will wane over time. Stakeholder commitment must be reasserted and reinforced repeatedly as the vision unfolds. You must nurture the connection your stakeholders have to the vision to remind them of the value of the work they do and to continue fueling their internal fires for that work. This is one of your key responsibilities as a project leader.

The mistake that's made often is to confuse a vision with the actual written statement. The vision is so much more than its description. It's never enough to email a vision to someone or give them a document with the vision typed on the cover. A vision demands special treatment and repetition. Think of how you can make the vision come alive. Here are some ideas:

![]() Have coffee cups or coffee cup tiles emblazoned with the vision, expressed either graphically or in words.

Have coffee cups or coffee cup tiles emblazoned with the vision, expressed either graphically or in words.

![]() Make posters expressing the vision and have the project team and stakeholders sign them. Post them everywhere there's a stakeholder.

Make posters expressing the vision and have the project team and stakeholders sign them. Post them everywhere there's a stakeholder.

![]() Have a 15-minute, one-on-one meeting with the sponsor so you can share the vision enthusiastically.

Have a 15-minute, one-on-one meeting with the sponsor so you can share the vision enthusiastically.

![]() Mention the vision in meetings. Use it in your language as you work through project challenges with team members. When you're making decisions together, ask others, “What should we choose if we want to honor our vision?”

Mention the vision in meetings. Use it in your language as you work through project challenges with team members. When you're making decisions together, ask others, “What should we choose if we want to honor our vision?”

Dealing with Diverse Personalities

When the vision has been stated, everyone needs to know what they're supposed to be doing. Prior to building a detailed project plan that spells out each stakeholder's specific output and the pertinent schedule (you'll do that in Step 6), it's important that you know how to delegate project tasks successfully and how to coach as the work gets under way to ensure it all stays on plan.

Building a collaborative project team involves working well with various personality types. Whether you're communicating with stakeholders or your project team, behavioral profiles help you understand how different people interact with one another and react to stress and conflict. They also provide insight on how to adapt to different communication preferences.

A warning is in order: All assessments are just models; in no way do they offer a complete picture of any unique individual. They never should be used to judge others or to limit someone's career opportunities. Instead, be careful to use them as one indicator of the most effective way to communicate with another person.

In this section, we'll look at one behavioral assessment—the DISC profiles—and at how you can use the understanding you gain from them to build a project team that works well. It's probably true that the human resources department at your company has other behavioral profiles available for your use as well.

In 1920, William Moulton Marston developed a theory to explain people's emotional responses to various stimuli. The current DISC assessments, offered by several companies, are based on his initial research. DISC is designed to help people explore personality and behavior types so they can better understand themselves and others.

In the DISC approach, each person's profile is based on the combination of the following four primary behavioral dimensions:

![]() Dominance: direct, driver, decisive—Ds are strong-minded, aggressive, strong-willed people who enjoy challenges, action, and immediate results.

Dominance: direct, driver, decisive—Ds are strong-minded, aggressive, strong-willed people who enjoy challenges, action, and immediate results.

![]() Influence: social, optimistic, and outgoing—An I is a “people person” who prefers participating on teams, sharing ideas, and entertaining and energizing others. This person likes to gain consensus.

Influence: social, optimistic, and outgoing—An I is a “people person” who prefers participating on teams, sharing ideas, and entertaining and energizing others. This person likes to gain consensus.

![]() Steadiness: stable, sympathetic, and cooperative—Ss tend to be helpful team players. They prefer being behind the scenes, working in consistent and predictable ways. They don't like rapid change, and they don't like conflict. They're often good listeners.

Steadiness: stable, sympathetic, and cooperative—Ss tend to be helpful team players. They prefer being behind the scenes, working in consistent and predictable ways. They don't like rapid change, and they don't like conflict. They're often good listeners.

![]() Compliance: concerned, cautious, and correct—Cs usually plan ahead, constantly check for accuracy, and use systematic approaches.

Compliance: concerned, cautious, and correct—Cs usually plan ahead, constantly check for accuracy, and use systematic approaches.

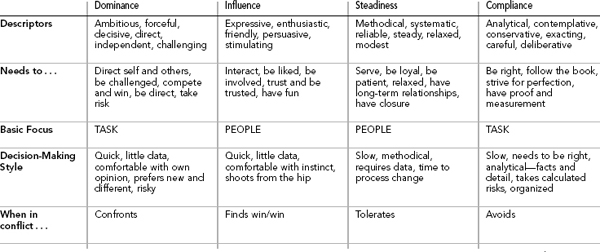

Worksheet 5.2 offers a quick DISC self-assessment for you to try. It's a short-cut, nonscientific way to get people thinking about their traits and ways of behaving in the world.1 As you read through the words, circle any words that you think describe you. Circle as many or as few as you like. When you're done, tally the number of words/phrases you've circled under each letter, D, I, S, and C. Everyone has a different combination of these descriptors. The letters under which you circled the most and the second-most number of words or phrases probably are your preferred behaviors.

WORKSHEET 5.2

DISC Behavioral Self-Assessment

Instructions: Circle all the words that you think describe you. The words you've circled indicate your behavioral preferences.

DISC assessments measure how you behave, and how others would describe your behavior. Each person on your team may manifest any of the behaviors mentioned and has a unique combination of all of them. Each of us has preferred behaviors that burn less energy and generate less personal stress. In other words, some behaviors are easy for us, some are more difficult. In the first part of the self-assessment in worksheet 5.2, users circle the words they believe best describe them. The words are arranged in four blocks: DISC. Let's talk about what each of those sections reveal. We'll work from the top-right quadrant and proceed clockwise.

A person with D behavior tries to complete tasks as quickly as possible. The two key words for D are urgent and task. A strong D competes against himself or herself every day to get more done and, at the end of a day, will wonder, did I check off more tasks to-day than ever before? Not being able to finish tasks causes stress for a D, and that shows up as anger at others. Someone with a lot of D gets angry when someone else is preventing him or her from completing tasks.

A person with I behavior will try to sway people as quickly as possible. The two key words for I are urgent and people. A strong I is looking to others to get the positive reinforcement that spells success and, at the end of a day, will ask, did I get more people to like me today than ever before? Not being special and liked by others causes stress for an I, which shows up as hurt behavior.

People with S behavior like things to stay on an even keel and prefers that everyone be happy. The two key words for S are diligent and people. A strong S is looking to others to learn whether he or she is successful at keeping everyone else fine. At the end of a day, this person will ask, did I make sure that everyone I know was OK today? Studies show that about 40 percent of the people working at your company manifest high S behaviors. Not being able to take care of others causes stress for an S, and that stress shows up as passive-aggressive collaboration behavior. Someone with a lot of S always smiles and nods positively at you, whether she or he agrees or not. She or he doesn't want to hurt your feelings.

A C likes to do tasks perfectly and doesn't like to be rushed. The two key words for C are diligent and task. At the end of a day, a strong C will ask, did I finish a task perfectly? If it wasn't possible to do the work perfectly, the C-behavior worker won't have finished it at the end of the day. Not being able to take whatever time is needed to produce perfect output causes this worker stress, which shows up as redirection. In other words, a C will create or point out a distraction that gets people involved elsewhere so she or he can finish the task undisturbed.

People classified in one of those four ways typically are found in predictable company roles or departments: Ds are executives, leaders, CEOs; Is are trainers and salespeople; Ss are managers, individual contributors; and Cs are programmers, accountants, and engineers.

Conflict comes from the clash of different behavioral perspectives. Obviously, a strong D and a strong S are going to have trouble working together because their perspectives are so different. Similarly, an I and a C will have difficulties. In each case, there will be a natural instinct for conflict with the other. Ironically, if a D learns to work with an S, or an I with a C, they complement each other perfectly, filling in for one another's weaknesses with their own strengths. Thinking of the likely roles these behavioral types will occupy, a project manager won't be surprised to see the conflict inherent in relationships between engineers and salespeople or programmers and trainers. Similarly, a manager easily can describe how the changing whims of a CEO make him or her crazy.

People with similar profiles also often have difficulty getting along. Two strong Ds with two different checklists can undermine a project quickly. Two strong Cs with different views of perfection can cripple a project. Two Is or two Ss will enjoy each other enormously, but they won't get much done without strong leadership.

As project leader, you have to help people understand that, as a team, they can fill in each others' gaps. As different behaviors begin to impede progress on a project, encourage the individuals to adapt to each other by helping them understand their conflicting perspectives. This is a coaching effort that requires you to approach each staff member from a perspective that's consistent with his or her strengths. In other words, don't tell a D to try to be nicer. Help the D understand how seeking collaboration with others will help him or her check off tasks more quickly. Tool 5.2 summarizes the four profiles and how each communicates most effectively. You and the members of your project team will find this information invaluable as you work together.

TOOL 5.2

Behavioral Differences Based on DISC Profiles

It's most important that you model adapted behavior yourself. Learn to adapt to the different project team members, and work to communicate with them in a way that is best suited to their communication and behavioral styles. Adapting is also useful when working with other stakeholders.

Delegating and Coaching

As you develop the project plan in Step 6, you'll begin to delegate work to different project team members and perhaps stakeholders. Most of the delegation will occur as soon as the project schedule (Step 6) is complete and shared, but tasks will come up along the way as well. Each person helping will need different amounts of support as she or he completes the assigned tasks. Some people need only to see their names on the plan with a description of a task. Others need more help.

As project manager, you are responsible for the project meeting its objectives. The larger the project, the more people doing the project tasks. Some of these tasks (and people) won't be able to start until someone else has completed his or her work. That's why it's so critical that a project manager be able to

![]() assign the tasks to the people who have the skills and knowledge to complete them

assign the tasks to the people who have the skills and knowledge to complete them

![]() articulate clearly to the person (or people) doing the task exactly what is expected for successful completion, and then track the progress of the task as it moves along to ensure that it's on time, within budget, and meeting the quality criteria

articulate clearly to the person (or people) doing the task exactly what is expected for successful completion, and then track the progress of the task as it moves along to ensure that it's on time, within budget, and meeting the quality criteria

![]() coach the person (or people) performing the task if there are concerns or questions

coach the person (or people) performing the task if there are concerns or questions

![]() manage the successful hand-off to the person (or people) who'll perform the next task.

manage the successful hand-off to the person (or people) who'll perform the next task.

Those are the steps of delegating. Delegation is not doing all the tasks yourself, taking over a task from a person who's struggling, or micromanaging someone as he or she tries to complete a task. Delegation is getting the project done through a team of successful, aligned team members. Let's take a closer look at those steps.

Assign Tasks

Think about what it will take to do a task. Look at the people available to you and decide who is best qualified to do this task. Ensure that each person's responsibility is specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and clearly defines the time it will take.

Articulate Expectations and Track Progress

Starting with a full understanding of the tasks to be done avoids a lot of misunderstandings down the road. Remember the SMART mnemonic we used to create project objectives in Step 3? Use it again when delegating tasks.

Coach Your Team Members

Good leadership also requires monitoring progress and coaching, both if there's a problem with task completion and if the task's been completed extremely well. Sometimes people mistakenly believe that coaching is only about problems, but truly effective coaching occurs when the coach gives both positive and constructive/corrective feedback.

Sometimes we overstep the scope of project- or work-related coaching and we venture into personal areas. Not only is that inappropriate in a work setting, but it also may be unethical because very few of us are qualified as therapists. Figure 5.1 illustrates four ways that coaches may try to interact with the people they coach—advising, counseling, teaching, and reflecting. The shaded areas—advising and counseling—are not within the scope of project coaching. Personal problems should be avoided or redirected to the appropriate human resources staff.?

FIGURE 5.1

Four Ways of Coaching

Teaching means helping team members develop their skills or knowledge, either by sharing what you know or by lining them up with the resources they need to learn. Coaching means asking, listening, and then giving frequent feedback (both positive and developmental) on task performance. The coach is not “steering”—the coach is helping the person being coached decide how to steer for himself or herself. Coaching can take place in formal, one-on-one scheduled meetings or within small off-the-cuff conversations. The most effective coaching often happens in the moment, when you're talking in the hall about the project or someone walks into your office with a question.

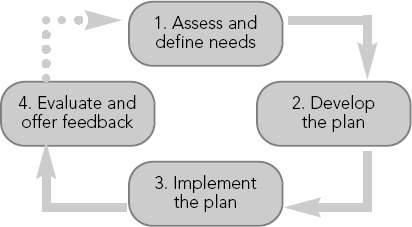

The asking, listening, and feedback activities of coaching follow the four-step process illustrated in figure 5.2. For each person you coach, (1) assess what he or she needs; (2) together, develop a plan to make that happen; (3) implement the plan; and (4) evaluate the outcome as you provide feedback. When the person you're coaching moves away from the plan, your responsibility as coach is to start this cycle again. When the person is doing a great job, it's also your responsibility to provide positive coaching.

FIGURE 5.2

Four-Step Coaching Model

As a coach, you'll have times when you don't understand how a person could be so far off track. Before defaulting to conflict, consider asking yourself these four questions:

1. Does this person know what to do?

2. Does this person know why the task is important?

3. Does this person know how to do the task?

4. Has this person tried to do it?

These will help you avoid the temptation to make assumptions about what a person is thinking and what makes her or him unable to meet the needs of the project plan. Try to understand before telling someone else what to do and how to do it. Many project managers avoid coaching because they worry that they won't know what to say or that there'll be conflict. Good coaches know that coaching is more about asking than telling. Be prepared with a list of basic, open-ended questions to initiate a good discussion. Many times, good questions help a task manager discover how to proceed—and that's the best solution of all.

In addition, be certain that you clearly understand the problem or achievement and that you know what you'd like to happen—that is, what changed behavior would you like to see the task manager use to address the problem, or what behavior the task manager used that succeeded and that you'd like to support and encourage.

The following four questions will help you ensure that the information you're about to share in your coaching conversation is appropriate:

1. Is it factual—based on accurate data?

2. Is it free of emotion—calm, neutral, and not given in anger?

3. Is it fresh—pertinent to recent events or actions?

4. Does it recommend actions going forward?

If you can answer “yes” to all four questions, your feedback is ready to present.

Manage the Task Hand-off

When the person you've been coaching has completed the task, ensure its quality and begin the coaching process again with the next task to be done.

Holding Productive Project Meetings

On a recent television show, I saw a ton of tiny fish, minding their own business in their school formation, suddenly come under attack by sharks. These little fish instantly changed their formation into a spinning tornado. Although the sharks were able to crash into the formation and eat up some of the little fish, it became a much more difficult feat as the swirling fish confused their senses. If any of the little fish had broken out of the group, they would have been gobbled up instantly.?

It would be nice if this worked for project teams under attack, and it's a strategy that's often used. But it always fails miserably. Let's say your project has just started. To be polite, and because you're still not really clear who needs to be involved in decision making, you have your first project meeting and invite everyone. People are friendly, exchange polite ideas, and most leave with a good feeling about this project. Then the trouble begins. Something happens that threatens the project deadlines or budget. Let's say the project is running much later than anticipated. You call an “all-hands” meeting for a number of poor reasons, including these:

![]() You don't want to deal directly with the people who are causing the delay. You think it's better to call a meeting for everyone and hope the remedial words land on the of-fenders. Maybe you don't even know who or what is causing the delay. You feel there's no time to figure out what the problem is!

You don't want to deal directly with the people who are causing the delay. You think it's better to call a meeting for everyone and hope the remedial words land on the of-fenders. Maybe you don't even know who or what is causing the delay. You feel there's no time to figure out what the problem is!

![]() You want to get everyone involved in the trouble. This way, it becomes a shared problem and won't land on you.

You want to get everyone involved in the trouble. This way, it becomes a shared problem and won't land on you.

![]() Instead of sitting down and figuring out who really needs to be at the meeting, you think it's easier to just email invite the same people who attended the last meeting.

Instead of sitting down and figuring out who really needs to be at the meeting, you think it's easier to just email invite the same people who attended the last meeting.

This dynamic creates a phenomenon dubbed a “Who Hunt” by some of my smart IT friends at Community Hospitals. Rather than spending time discussing a solution to whatever the problem is, the large group spends most of its time figuring out whose fault it is (certainly not theirs). If any solutions are tossed around, people leave with the delusion that change will occur—but no one leaves with a clear understanding of exactly who will own those changes. When more project deadlines are missed, you call another all-hands meeting—and again nothing is really resolved. Progress continues to decline.

Unlike the action that worked to save most of the little fish, schooling your entire project team in giant, tornado-like meetings doesn't keep the sharks away. Here's why:

1. Decisions and solutions can be created with greater innovation and speed when the only people who have both the authority and passion to create them are working together. In other words, get the people together who can solve the problem, but no one else. Less is more.

2. Giant project meetings are outrageously expensive. If you have 15 people in a project meeting for an hour, you have lost 15 hours of velocity on your project. Two days. This is pretty serious for a late project. Meetings are not free.

3. Giant project meetings are not a good communication vehicle. Problem-solving meetings when a project is late aren't good ways to communicate project status or goals or even to cross train. If the goal is to solve a problem, hold a meeting to do just that. If the goal is to communicate project status or goals, organize the meeting specifically for that or consider other media. Training is a specific goal as well. Don't use meetings to be all things to all people.

TOOL 5.3

Project Meeting Guidelines

![]() Identify the problem characteristics and hold a quick, informal cubicle meeting with the people who can help you get to the facts and who know how to solve the problem.

Identify the problem characteristics and hold a quick, informal cubicle meeting with the people who can help you get to the facts and who know how to solve the problem.

![]() If a person is slowing down a project because of performance problems, deal with it directly through effective coaching and performance-improvement goals.

If a person is slowing down a project because of performance problems, deal with it directly through effective coaching and performance-improvement goals.

![]() Grow your people. Give them the authority and responsibility to make decisions themselves and own their results. Be specific.

Grow your people. Give them the authority and responsibility to make decisions themselves and own their results. Be specific.

![]() When you're invited to a meeting, decline if you don't know what the meeting is about and how you can contribute. Defend your time.

When you're invited to a meeting, decline if you don't know what the meeting is about and how you can contribute. Defend your time.

Use the guidelines in tool 5.3 to think about each meeting before you call it.

Communication

Good project leadership drives good project communication. Problems that challenge collaboration and breed conflict are going to occur repeatedly. I estimate that conflict adds 30 percent overhead to the work of each individual involved. Use the information in this step to help individuals work together to achieve the project vision by choosing to collaborate.

What If I Skip This Step?

Thinking about leadership isn't as easy as counting budget dollars, days, and heads. However, if you think honestly about what has made your past projects struggle, you know it always comes down to one factor—people. Leadership involves investing your time to get the people where they need to be.

What are the advantages of the practices you perform in this step? Here are a few:

![]() Setting a project vision as the groundwork for effective project leadership starts a project well. Effective delegation and coaching drive the likelihood of success.

Setting a project vision as the groundwork for effective project leadership starts a project well. Effective delegation and coaching drive the likelihood of success.

![]() Using a DISC behavioral profile with your project team, whether at the beginning or during times of trouble, gives everyone a neutral language for explaining what he or she needs. It also helps people avoid conflict that comes from assuming certain behaviors are confrontational.

Using a DISC behavioral profile with your project team, whether at the beginning or during times of trouble, gives everyone a neutral language for explaining what he or she needs. It also helps people avoid conflict that comes from assuming certain behaviors are confrontational.

![]() Spending time planning and managing project meetings has been proved to be a leading predictor of project success. Letting project meetings degrade into Who Hunts will drag a project down quickly. The project manager is the only person who has the perspective and the authority to put pressure on project meeting participants to keep things collaborative.

Spending time planning and managing project meetings has been proved to be a leading predictor of project success. Letting project meetings degrade into Who Hunts will drag a project down quickly. The project manager is the only person who has the perspective and the authority to put pressure on project meeting participants to keep things collaborative.

Lurking Landmines

![]() Stakeholders and key business experts don't have time to come to the meetings. Approach them collaboratively and without blame. At the same time, be clear that the project deliverables can't be created without their involvement. Stress the impact on the schedule, without making it sound “or else.” If key business experts really are unable to come to the meetings right now, the project probably should be postponed.

Stakeholders and key business experts don't have time to come to the meetings. Approach them collaboratively and without blame. At the same time, be clear that the project deliverables can't be created without their involvement. Stress the impact on the schedule, without making it sound “or else.” If key business experts really are unable to come to the meetings right now, the project probably should be postponed.

![]() A project team member has a history of conflict with another member of the team. At the start, talk about the conflict separately and honestly with each person involved and explain the behavior you expect from each of them. Carefully monitor the situation, and provide feedback for both good and less appropriate behaviors. If the two can't resolve their issues, consider removing one or both from the team. This type of conflict often spreads like cancer on a project team.

A project team member has a history of conflict with another member of the team. At the start, talk about the conflict separately and honestly with each person involved and explain the behavior you expect from each of them. Carefully monitor the situation, and provide feedback for both good and less appropriate behaviors. If the two can't resolve their issues, consider removing one or both from the team. This type of conflict often spreads like cancer on a project team.

Step 5 Checklist

![]() As leader, model collaboration in all you do.

As leader, model collaboration in all you do.

![]() Establish an effective vision for all the stakeholders.

Establish an effective vision for all the stakeholders.

![]() Identify the behavioral styles of the project team and stakeholders.

Identify the behavioral styles of the project team and stakeholders.

![]() Delegate and coach project activity successfully.

Delegate and coach project activity successfully.

![]() Build a strategy for project meetings that increases collaboration through effective communication.

Build a strategy for project meetings that increases collaboration through effective communication.

The Next Step

Next you will define the project in very specific terms. Now that you know the business case, the scope, and the risks and the constraints, and are primed to lead the project, you're ready to develop the detailed project plan. You'll figure out what tasks need to be done, in what order, and by whom to ensure the successful delivery of the project.

1To enhance your understanding of this assessment, I strongly recommend that you license and use full DISC profiles that are available from a distributor (see the Resources section). Additional readings concerning these behaviors also are listed in that section. I suggest you try Julie Straw and Alison Brown Cerier's The 4-Dimensional Manager: DISC Strategies for Managing Different People in the Best Ways(San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2002).