Opportunities and challenges for Bolivia’s water sector

Introduction

Large parts of the world population live in areas where the freshwater supply is not secure. A recent study found that as much as 80 percent of the world’s population is exposed to high levels of threat to water security (Vörösmarty et al., 2010). According to a UNICEF/WHO report (2012: 2) almost 780 million people lack access to safe drinking water and 2.5 billion – 40 percent of the world’s population – have no access to improved sanitation. Adding to this grim picture is the threat of climate change and a growing population. Degradation of water bodies and changes in rainfall patterns, which affect the hydrological cycle, increase the vulnerability of regions affected by intense floods and droughts (UNESCO, 2009; Huntjens and Pahl-Wostl, 2010). Failing to ensure access to water and sanitation has immense human costs, both in social and economic terms, and therefore, water resources can drive or limit social and economic development especially in developing countries. The global crisis in water consigns large segments of humanity to lives of poverty, vulnerability and insecurity (UNDP, 2006) and has led to a crisis in water management in terms of delivery of water services in many countries, where competition and potential disagreement between two or more stakeholder groups over the use of the scarce resource is observed (Steelman and Ascher, 1997; UNDP, 2004). Ensuring access to water and sanitation for all people is not simply a question of availability of water resources, technology, and infrastructure, but also of setting priorities, tackling poverty and inequality, addressing societal power imbalances, and, above all, political will (UNESCO, 2009).

In this context, water managers are looking for ways to maintain and improve the state of water resources under a changing environment (Pahl-Wostl, 2007). So far this has been a challenging task since water management systems are characterized by complex governance and need coordination of different components of the resource, interaction of various actors at all levels, consideration of links in the water chain and establishment of complex institutional arrangements (Beierle, 1998; Meadowcroft, 2002; Butterworth et al., 2010). The traditional “command-and-control” approach typically targeted at high predictability and controllability has proven to fail in times of uncertainty and increasing complexity of environmental problems and global change. In the past two decades, new and more integrated and participatory approaches to water management have been developed to overcome these shortcomings, such as Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) and adaptive water management (Pahl-Wostl et al., 2007; Merrey, 2008). IWRM has become quite popular among international cooperation organizations and water sector professionals, and has been implemented in many countries around the globe as a main governmental strategy to manage water resources (Watson, 2004; Merrey, 2008). The Global Water Partnership (GWP) (2000: 22) defines IWRM as “a process which promotes the coordinated development and management of water, land and related resources, in order to maximize the resultant economic and social welfare in an equitable manner without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems”. One of the main characteristics of this approach is its promise to bring real participation and transparency to the processes in the water sector and consider basins as the most suitable geographic unit for implementation (Coelho et al., 2008; Merrey, 2008). It claims that participatory approaches can contribute to better informed policy, more effective water governance, and social, psychological, and political empowerment of poor and vulnerable populations that have traditionally been marginalized sectors of the population (Steelman and Ascher, 1997; Feás et al., 2004; EMPOWERS Partnership, 2007).

However evidence from the ground indicates that increased participation in the water sector can have mixed results, and many considerations should be taken into account to achieve real engagement and avoid conflicts (Michener, 1998; Ramírez, 1999). To be effective, IWRM should consider the specific institutional, cultural, and socioeconomic contexts (Pahl-Wostl et al., 2007; Ingram, 2008), as well as address the interests and concerns of the different stakeholders at the moment of negotiation and decision making because each one of them assigns different values to different ecosystem services and risks (Lebel et al., 2006). However, this is rarely achieved in practice because power is unevenly distributed among the stakeholders involved in (water) management (Ingram, 2008). As power can be defined as the degree of control over material, human, intellectual and financial resources exercised by different sections of society (VeneKlasen and Miller, 2002), the understanding that the control of these resources becomes a source of individual and social power is crucial. In some contexts, powerful political interests attempt to discredit disadvantaged groups, making it impossible for citizens without resources or affiliation to get their voices heard, even if they represent a substantial population. Then the battle over access to resources can become a driver for marginalized groups to challenge existing system and fight for their inclusion and for bringing their needs to the decision making table.

The concept of empowerment is central to the understanding that imbalances in power relations affect people’s capacity to make effective choices and benefit from poverty reduction efforts. The World Bank defines empowerment as increasing the capacity of individuals and groups to make choices and transform these choices into desired actions and outcomes (Power, Rights and Poverty, 2004).

This chapter discusses the role that conflicts over water played in the empowerment of indigenous communities in Bolivia. The chapter draws on lessons from a water project in the Ravelo River Basin that provides most of the drinking water to the city of Sucre, Bolivia’s historic capital. We argue that the disputes over control and access to water resources have resulted in recent national social reforms that in turn have contributed to reshaping the relations among stakeholders in the water sector through the redistribution of power. Our case shows how the legal inclusion of the indigenous villagers has raised their consciousness, spurred them to action to claim their rights over the water resources, and finally brought about social change in the country.

Social reforms and the empowerment of indigenous people in Bolivia

Bolivia is a South American country with high levels of inequity and poverty. Almost two-thirds of its population lives under the poverty line, about 60 percent have their basic needs unsatisfied, illiteracy and child mortality rates are higher than the world’s average, and ethnic, gender and regional divisions are very deep.

The Bolivian environment is now facing serious threats caused by uncontrolled exploitation of natural resources, deforestation due to the agro-industrial expansion, and water pollution from domestic and industrial sources (PROSALUS, 2009). Nevertheless, Bolivia remains a global leader in certified forestry and one of the countries with greatest water resources availability on the planet (PROSALUS, 2009).

In spite of general availability of water resources in Bolivia almost half of the territory (western and southern part) is experiencing water scarcity. There are multiple reasons for this: increased competition between water users, lack of water infrastructure, pollution of water bodies from the mining and oil industries, and climate change. The situation is especially hard for the rural population almost 80 percent of which are involved in agriculture as their main economic activity, and therefore highly dependent on water resources (Van Damme, 2002). The country is also confronted by adverse impacts from climate change with implications for water security including glacial retreat, and more frequent and intense floods (UNDP, 2004). Recently the demand for water in the country from the agricultural, domestic and industrial sectors has risen equally in the different regions giving rise to new sources of conflicts (Van Damme, 2002).

Bolivia is currently facing a transition stage after a period of social and political instability. The distribution of power favors some individuals or groups over others, creating an environment of inequity and discrimination (Boelens, 2002). Almost two-thirds of the country’s population (60 percent) is composed of indigenous people of whom the majority live below the poverty line (INE, 2008). Over the years, one of the main conflict drivers for social crisis has been the constant disputes over the rights to use and benefit from natural resources for marginalized sectors of society. During the last 10 years, this once ignored majority has found new forums to express their opinions and concerns, to consolidate their efforts, and to assert their rights (Zibechi, 2005; Fuentes, 2008). The ever growing strength of the indigenous people’s social movement in the country has triggered social change (Zibechi, 2005). Deep legal and institutional reforms at national level have resulted in the empowerment of the country’s indigenous communities that have heavily impacted the means of their involvement into the decision-making in the water sector. Nowadays, the country is struggling for the democratization of society through the broader involvement of its citizens in the decision-making processes and social inclusion of previously ignored indigenous people.

Briefly reviewing the main events of this process of change in Bolivia, the starting point can be found in the early 2000s with continuous protests and public demonstrations of organized indigenous groups, claiming access to natural resources, especially to water and natural gas (Bustamante, 2002). After the “Water War” in 2000, in which social movements were able to overturn the privatization of the water utilities in the city of Cochabamba and contributed to the election of Evo Morales as the first indigenous president of the country in 2005, Bolivia and its profound social reforms gained international attention. The once marginalized indigenous people became important players in the national decision-making process (Crabtree 2005; Zibechi, 2005).

After these events, the water sector was used as a platform to empower indigenous people through legal and institutional reforms. In this regard, the Ministry of Water (now the Ministry of Water and Environment) was established and water was recognized as an essential element for people’s wellbeing and the country’s economic development. Later, the concept of integrated water resources management (IWRM) was introduced as a strategy to achieve broader stakeholder and public involvement in planning and decision-making. Specific articles on water management and indigenous rights were included in the National Constitution adopted in 2009. The constitution declares human rights to water, stipulates that all Bolivians are entitled to have access to clean drinking water and sewer systems, and prohibits privatization or granting concessions on them. It confers special rights to the local indigenous communities to use, allocate and manage their natural resources. As a result, indigenous people in the country are officially recognized as legitimate actors and have started openly expressing their willingness to participate in the decision-making.

However, the recent empowerment of local communities in Bolivia has brought not only the opportunities, but also challenges for both the communities themselves and other stakeholders. According to Bartle (2008), social and political change require corresponding change in mindsets of the entire society, and in Bolivia not all actors are prepared to embrace or acknowledge the rights of indigenous people due to the country’s long history of unequal relations.

We use a case study on the construction of a dam in the Ravelo River Basin to supply water to Sucre and the conflict around it in order to analyze how the recent remarkable political and legal reforms at the national level have empowered marginalized local communities, driven their inclusion into the negotiation process, and provoked social change leading to the their recognition as the equal stakeholders in the water decision-making at the basin level.

The Ravelo River Basin case study

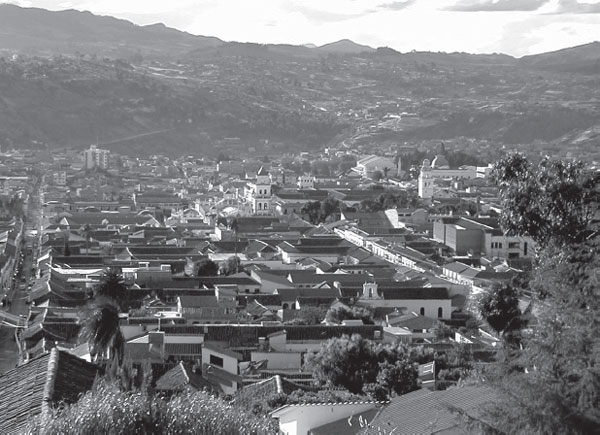

The Ravelo River Basin is situated in the south east of Bolivia, and is shared by two neighboring municipalities, Ravelo and Sucre, located in the Departments of Potosí and Chuquisaca respectively (Figure 25.1). The municipality of Ravelo (Figure 25.2), where the villages of Sasanta and Yurubamba are located, has a population of 20,536 habitants of which, 100 percent live in rural areas, 68 percent are below the extreme poverty line and 78 to 93 percent of the inhabitants have no access to safe drinking water (INE, 2008).

The municipality of Sucre (Figure 25.3), located in the Department of Chuquisaca, with a population that increased to 230,000 habitants, 90 percent of whom live in urban areas and 27 percent are below the poverty line (HAMS, 2007; INE, 2008). In terms of basic services, 90 percent of the population had access to safe drinking water provided by the local water company ELAPAS (HAMS, 2007).

With the aim to improve water supply in Sucre in the long-term, the city’s water company “ELAPAS” started working on a project to construct a reservoir with a capacity of 6.5 million m3 in the Ravelo River between the villages Sasanta and Yurubamba in 2003 (ELAPAS, 2009). However, the project was not implemented until 2010 due to strong opposition of the villagers. According to meeting records, the initial negotiations in 2003 involved only the representatives of both municipalities and some local leaders, neglecting the opinion of indigenous people who anticipated losing their land and homes because of construction of the reservoir. Later, in 2004 and 2007, the city’s water company tried to promote the project through a socialization program that aimed to persuade the villagers to accept the dam construction. This acceptance was required by the national and international donors to receive financial aid. The indigenous people from Sasanta and Yurubamba requested the first socialization meetings to be carried out in the local communities in order to facilitate the participation of most of the villagers and therefore to allow them to reach a decision at a community level. Nevertheless, the water company failed to comply with this requirement and instead, decided to hold the meetings in Sucre. As a result, the villagers refused to attend those meetings, delaying the project approval once again. The negligence shown by the city’s water company over the years and its resistance to acknowledging the local villagers’ interests and to recognizing them as active participants in the project resulted in growing mistrust among the villagers and the loss of their intention to engage in further negotiations.

By the end of 2008, the city water company managed to secure funding for the project and tried to start the construction work, but met strong opposition from the rural villagers in Sasanta and Yurubamba. The latter claimed that the decision to implement the project was illicit because it was taken without any consultation with the affected people who would lose their land and properties. Although the project had been endorsed by previous governments, the villagers argued that it would not be implemented without their approval. Relying on the new constitution that stated their rights and acknowledged their role as legitimate stakeholders in the allocation of water in the basin, the villagers fought back.

Later, in 2009, the villagers’ position was strengthened even further by the broad social reforms in the country. The Bolivian government committed itself to protecting the rights of indigenous peoples and to support their demands in this and similar cases. A representative from the Ministry of Water and Environment was appointed to support the villagers in the negotiations that followed. Consequently, the water company was forced to find ways to bring the villagers’ demands to the negotiating table in order to find a compromise to make the project implementation viable. The villagers mainly demanded compensations for the loss of their fields, which were going to be inundated after construction of the reservoir, and for water withdrawal, which was to be allocated to Sucre. Besides, during the negotiations, it was clear that they also expected to gain some benefits if they decided to approve the dam construction, in terms of compensation such as the implementation of development projects for the municipality of Ravelo like the improvement of their public infrastructure (roads, water supply systems, etc.). They realized that, if the quality of life of the inhabitants of Sucre would be improved with the dam construction, they could also find ways to use the project to improve their lives.

First, communal meetings were held in Yurubamba and Sasanta where people discussed among themselves and decided what compensation would be fair to them. After that, several rounds of negotiation were organized engaging representatives of both the water company and the communities. The representatives from the Ministry of Water and Environment played the crucial role of mediators in these negotiations. They provided technical advice to the villagers helping them to understand the proposals of the water company on one hand, and on the other they guarded the villagers’ interests and rights. Finally, the conflict was largely resolved in 2010 after a compromise had been achieved, and the financing for the project implementation was approved. The official version of the Sasanta-Yurubamba Project shows considerable benefits that the villagers of Sasanta and Yurubamba will gain from the project implementation. Among others, the water company, the regional government of Chuquisaca, and the municipality of Sucre agreed to buy their lands at a fair market price in order to compensate for the loss of indigenous terrains due to inundation, to finance the construction of health, road, public and educational infrastructure; and to implement small development projects such as improved agricultural techniques, irrigation, and pisciculture.

Conclusions

To some extent, the water sector in Bolivia has served as one of the driving forces behind the recent drastic social changes. IWRM as a strategy to broad stakeholder and public involvement in planning and decision-making was put in place. As well, legal and institutional frameworks for the sector have drastically changed with newly introduced national policies, legislation, the creation of the Ministry of Water, and the inclusion of indigenous people as the main stakeholders in the decision-making processes. This has led to the empowerment of the once marginalized indigenous communities that now also have the support of governmental institutions. These radical reforms undertaken to empower indigenous people revived their willingness to participate in the decision-making, where they are now recognized as legitimate actors.

In the Ravelo River Basin, the conflict between the water company and the local indigenous communities delayed the implementation of the important water supply project for the country’s capital city for seven years. The national political and legal reforms have reshaped relations among the stakeholders through the redistribution of power and have made it possible for the community of Ravelo to stand up and claim their rights. This reactivated the negotiation and resulted in finding a compromise that was accepted by all parties involved.

However, the biggest challenge is still ahead, and that is to create an environment conducive to closing the gaps between promise and practice since changed policies do not necessarily mean they will be effectively and fairly implemented. On one hand, community empowerment requires significant cultural changes representing a complicated and long-term process while also having to cope with the existing social problems in the country such as poverty, illiteracy, and mistrust. On the other hand, the recently approved legislation in the water sector in Bolivia lacks detail and a clear strategic view on the sector’s development that poses some challenges for its implementation.

References

Bartle, P. (2008) ‘Human factor and community empowerment’, Review of Human Factor Studies, 14 (1): Special Issue.

Beierle, T.C. (1998) Public participation in environmental decisions: An evaluation framework using social goals, Resources for the Future, Discussion Paper 99-06. Online. Available HTTP: http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/10497/1/dp990006.pdf (accessed 15 November 2012).

Boelens, R. (2002) Water law and indigenous rights: research, action and debate, Wangeningen, the Netherlands: University of Wageningen.

Bustamante, R. (2002) Legislación del agua en Bolivia. Centro andino para la gestión y uso del agua, Cochabamba, Bolivia: Centro Agua, UMSS..

Butterworth, J., Warner, J., Moriarty, P., Smits, S. and Batchelor, C. (2010) ‘Finding practical approaches to Integrated Water Resources Management’, Water Alternatives, 3 (1): 68–81.

COANDINA (2009) ‘Integrated management of the Ravelo river basin’, Potosí: Bolivia.

Coelho, A.C., Fontane D.G., Vlachos E. and Maia R. (2008) ‘Delineation of water resources units to promote IWRM and facilitate transboundary water conflicts resolution’, paper presented at IV International Symposium on Transboundary Waters Management, Thessaloniki, Greece, October 15–18t, 2008.

Crabtree, J. (2005) Patterns of protest: politics and social movements in Bolivia, London: Latin America Bureau.

ELAPAS (2007–2009) ‘Executive summary: “Construction of a system for the regulation and increase of the water discharge in the concession of the Ravelo River for the city of Sucre”’, Sucre: Bolivia.

EMPOWERS Partnership (2007) The EMPOWERS approach to water governance: guidelines, methods and tools. Online. Available HTTP: http://waterwiki.net/images/d/d2/EMPOWERS_Guidelines%2C_Methods_and_Tools.pdf (accessed 15 October 2010).

Feás, J., Giupponi C. and Rosato P. (2004) ‘Water management, public participation and decision support systems: the MULINO approach’, paper presented at iEMSs International Conference Complexity and Integrated Resources Management, 14–17 June 2004 University of Osnabrück, Germany.

Fuentes, F. (2008) Bolivia: the struggle for change, Global Research, 2 December 2008. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.globalresearch.ca/bolivia-the-struggle-for-change/11269 (accessed 10 June 2009).

GWP (2000) Integrated water resources management, GWP Technical Committee Background Paper 4, Stockholm.

HAMS (2007) Plan de desarrollo municipal 2003–2007, Sucre, Bolivia.

Huntjens, P. and Pahl-Wostl C. (2010) ‘Climate change adaptation in European river basins’, Regional Environmental Change, 10: 263–284.

INE (2008) Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Bolivia. Online. Available HTTP: www.ine.gov.bo (accessed 11 September 2008).

Ingram, H. (2008) ‘Beyond universal remedies for good water governance: A political and contextual approach’, paper presented at the Rosenberg Forum for Water Policy, Zaragoza, Spain, June 25–26.

Lebel, L., Anderies J.M., Campbell, B., Folke, C., Hatfield-Dodds, S., Hughes, T.P. and Wilson, J. (2006) ‘Governance and the capacity to manage resilience in regional social-ecological systems’, Ecology and Society, 11 (1): 19.

Meadowcroft, J. (2002) ‘Politics and scale: some implications for environmental governance’, Landscape and Urban Planning, 61: 169–179.

Merrey, D.J. (2008) ‘Is normative integrated water resources management implementable? Charting a practical course with lessons from Southern Africa’, Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, 33: 899–905.

Michener, V. (1998) ‘The participatory approach: contradiction and co-option in Burkina Faso’, World Development, 26 (12): 2105–2118.

Pahl-Wostl, C. (2007) ‘Transitions towards adaptive management of water facing climate and global change’, Water Resources Management, 21: 49–62.

Pahl-Wostl, C., Sendzimir J., Jeffrey, P., Aerts, J., Berkamp, G. and Cross, K. (2007) ‘Managing change toward adaptive water management through social learning’, Ecology and Society, 12 (2): 30.

Power, Rights, and Poverty: Concepts and Connections (2004) A working meeting sponsored by DFID and the World Bank March 23–24, 2004, Ruth Alsop (ed.) World Bank, Washington, DC.

PROSALUS (2009) Análsis de la realidad de Bolivia. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.prosalus.es/gestor/imgsvr/publicaciones/doc/An%C3%A1lisis%20de%20la%20realidad%20Bolivia.pdf (accessed 3 September 2012).

Ramirez, R. (1999) ‘Stakeholder analysis and conflict management’, in D. Buckles (ed.) Cultivating Peace: Conflict and Collaboration in Natural Resource Management, International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, Canada.

Steelman, T. and Ascher W. (1997) ‘Public involvement methods in natural resource policy making: Advantages, disadvantages and trade-offs’, Policy Sciences, 30: 71–90.

UNDP (2004) Water governance for poverty reduction: key issues and the UNDP response to Millennium Development Goals, United Nations Development Programme. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.undp.org/water/pdfs/241456_UNDP_Guide_Pages.pdf (accessed 1 November 2008).

UNDP (2006) Human Development Report 2006. Beyond scarcity. Power, poverty and the global water crisis, United Nations Development Programme. Online. Available HTTP: http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/HDR06-complete.pdf (accessed 15 January 2010).

UNESCO (2009) Outcome of the international experts’ meeting on the right to water, UNESCO, Paris, 7–8 July 2009, SEP Nimes, France, 16 p.

UNICEF, WHO (2012) Progress in drinking-water and sanitation: 2012 update, WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation (JMP), 2012.

Van Damme, P. (2002) Disponibilidad, uso y calidad de los recursos hídricos en Bolivia, World Summit on Sustainable Development, Johannesburg.

VeneKlasen, L. and Miller, V. (2002) A new weave of power, people and politics, the action guide for advocacy and citizen participation, Oklahoma City, OK: World Neighbors,.

Vörösmarty C.J., McIntyre, P.B., Gessner, M.O., Dudgeon, D., Prusevich, A., Green, P., Glidden, S., Bunn, S.E., Sullivan, C.A., Reidy Liermann, C. and Davies, P.M. (2010) ‘Global threats to human water security and river biodiversity’, Nature, 467: 555–561.

Watson, N. (2004) ‘Integrated river basin management: a case for collaboration’, International Journal of River Basin Management, 2 (4): 243–257.

WWAP (2009) The United Nations World Water Development Report 3: Water in a Changing World, World Water Assessment Programme Paris, UNESCO, and London: Earthscan. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.unesco.org/water/wwap/wwdr/wwdr3/pdf/WWDR3_Water_in_a_Changing_World.pdf (accessed 15 January 2010).

Zibechi, R. (2005) Bolivia: dos visiones opuestas del cambio social. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.cipamericas.org/es/archives/1231 (accessed 20 February 2009).