34 Uncovering the essence of the climate change adaptation agenda

The policy sciences as a problem-oriented approach

Introduction

Over the last few years, calls for research into climate change adaptation have seen a general shift from defining vulnerability to likely impacts of future climate change (Kelly and Adger, 2000) towards broader and more problem-oriented approaches that focus on present conditions and experiences (Schröter et al., 2005; O’Brien et al., 2007; Roman et al., 2011). This broader approach includes climate change as a process operating within a biophysical and socio-economic system and recognizes the intricate and far-reaching interactions that occur in the coupled human-biophysical system and beyond (O’Brien et al., 2007; Patt, 2009). Adaptation in this broader context is also better placed to serve the common interest, given the emphasis that is placed on the importance of context and congruent valued outcomes for those concerned (Lynch and Brunner, 2007; Lynch et al., 2008). For the purposes of this discussion, the common interest is broadly understood as interests widely shared by and beneficial to the members of a community. It must be constructed in each community on the basis of their interests that are both appropriate (consistent with basic community values) and valid, i.e. consistent with the evidence available (Roman et al., 2011).

An important consideration when differentiating between common and special interests, rests on the values that underpin these interests and how these form part of the context in which a given problem unfolds. Values are increasingly being recognized as influential and critical in advancing our understanding of how action on climate change unfolds, or could potentially unfold (e.g. see Morss, 2005; de Chazal et al., 2008; O’Brien, 2009; O’Brien and Wolf, 2010), notwithstanding the many challenges in problem framing and definition when distinct worldviews and values are implicated (Roman et al., 2011; Adler et al., 2012). Also to be excluded are pre-conceived “solutions” that masquerade as problems, i.e. when “people see a condition as problematic only because it is the mirror image of a solution they already believe in” (Bardach, 1981: 164). As Bardach (1981) points out, the definition of the problem should be as general and tactful as possible by removing causal and prescriptive qualifiers of the problem and instead focusing on identifying the feelings of discontent, effectively describing the perspectives and myths entrenched in them.

In this chapter we present insights on the common interest, based on conclusions and lessons learned from earlier versions of work conducted in Alpine Shire, Victoria, Australia (see Roman, 2010; Roman et al., 2010; Roman et al., 2011). The insights discussed here center on key methodological and conceptual considerations for how we used problem-oriented approaches to move forward on adaptation in the context of irreducible uncertainties as well as cognizant of values and interests at stake. We begin this chapter by first providing an overview of the main features of the policy sciences as a problem-oriented approach that clarifies and focuses on relevant and evidence-based factors in a given context. This is then followed by a case study application, and finally some of the main conclusions and reflections from this experience.

The policy sciences as a problem-oriented approach

Problem-oriented approaches are said to reflect philosophical underpinnings in pragmatism, a discourse characterized as an extension of critical theory and referring specifically to the usefulness, workability, and practicality of ideas, policies, and proposals as criteria of their own merit, even though it is not necessarily committed to any one philosophy or reality (de Leon, 1994; Creswell, 2007; de Leon and Vogenbeck, 2007). Instead of focusing meticulously on methods alone, the important aspect of research in pragmatism is the problem being studied and the questions asked about this problem (Creswell, 2007). A fundamental point of difference that differentiates pragmatism from other philosophical stances is the ethical dimension that is embraced (Brunner, 2006). In pragmatism, “change” is treated as an inevitable condition of life, so pragmatist approaches seek for ways in which change can be directed for compatible individual and social benefits, both in the present and for the future (Clark et al., 2000; Brunner, 2006). Its distinguishable notions of community, dialogue, and democracy have significant implications for and application “in a world characterized by uncertainty, change, and instability” (Hytten, 1994: 1). It represents a philosophical stance that is transdisciplinary, whereby ethical considerations define the purpose for present and future actions “as if people matter” (Max-Neef, 2005: 8).

In policy, problems are seen as human constructions of how a situation is perceived versus a preferred outcome (Lasswell, 1971). However, given how uniquely perspectives are shaped by values, a problem can therefore yield many definitions among the individuals concerned thus influencing whether a problem should (or should not) be addressed (Morss, 2005). The policy sciences approach offers a means to analyze and evaluate these complex contexts wherein people derive meaning and perspective and the outcomes that result when interacting with others (Lasswell and McDougal, 1992; Clark et al., 2000). This is not to imply that addressing complexity necessarily translates to a complete analysis, given the inherent human limitations that inhibit complete examination of all details in any given situation. Instead, the policy sciences offer procedures that bring relevant content to the focus of attention through selectivity and comprehensiveness (Lasswell and McDougal, 1992).

The framework is based on three principles (Lasswell, 1971). First is contextuality, recognizing that decisions are derived and made within a larger social process that is also largely values-based. Mapping the social and decision-making processes (the context) provide the detail and focus required to inform on perceived discrepancies between the status quo and goals aspired to (the problem). Second is problem orientation, an analytical task used to procedurally identify the essence of a problem. In problem orientation, the emphasis is on synthesizing, rather than sequencing intelligence centered on a problem (Auer, 2007). This requires a multi-method and interdisciplinary approach, one that derives knowledge from a number of intellectual foundations. Third is diversity in the methods employed to collect and analyze the empirical evidence that clarifies a problem. Freedom through insight, rather than predictions based on generalizations, is how the role of “science” is characterized in policy sciences, highlighting the need for integrated approaches for problem orientation (Lasswell and Kaplan, 1950; Brunner, 1991, 2001; ABS, 2009). It is a comprehensive yet sufficiently precise approach that directs attention to all the important features of the total context (Lasswell and McDougal, 1992).

The policy sciences approach has been widely applied across many disciplines, often only making implicit references to the framework itself even though elements of the framework are embedded and recognizable (see examples cited in Roman et al., 2011). These include a number of studies that have explored problems of environmental focus, including climate change. The significance of the approach through its applications is that it places emphasis on the goals and values of all participants with valid interests, rather than their risks, vulnerabilities, or resilience even though these factors form part of the study, providing a flexible and powerful tool for analysis.

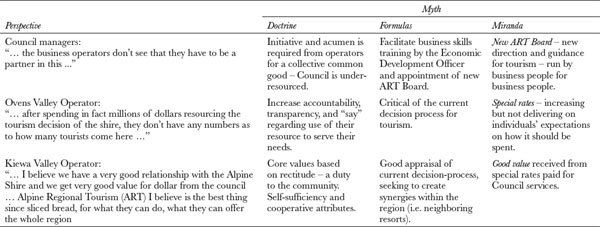

The policy sciences framework also contributes to a better understanding of the different motivations and even myths that operate in a local community, clarifying the fine distinction that should be made when describing special versus common interests. From a policy sciences perspective, myth is akin to a stance or worldview (Lasswell, 1971), and is described by its doctrine – core beliefs, formula – preferred ways of achieving doctrinal outcomes, and miranda – symbols that manifest core beliefs (see for example Clark et al., 2008).

A case study of the tourism sector at Alpine Shire, Victoria, Australia

Framing the problem

In Australian mountain regions, much of the research conducted on vulnerability to climate change has largely focused on the biophysical impacts that climate change is likely to impose, for example the issue of diminishing winter snow in the Australian alpine environment (Worboys and Pickering, 2002; Hennessy et al., 2003; Pickering et al., 2004). Adaptation to climate change has also gained attention as a significant strategic issue for regions that rely on tourism as a principal economic activity (Becken and Hay, 2007; Dwyer et al., 2009), however given the prevailing focus on biophysical impacts, the consideration of viable climate adaptation options for these mountain regions has been somewhat narrow and devoid of commuunity values in context (Roman et al., 2010). Previous work carried out in Alpine Shire identified the importance of tourism as a vital activity for economic development and viability (Tryhorn, 2008). Expanding from those initial findings, the aim of the research reported through this case study is to further explore the concept of contextual vulnerability and implications for adaptation with a view to include values and perspectives, using the policy sciences approach.

Alpine Shire, located 270 km northeast of Melbourne (see Figure 34.1), covers 4397 km2, and with a resident population of 12,988 (DPCD, 2007). Recreational skiing and the formation of local skiing clubs in the 1880s were the first activities to promote tourism (Webb and Adams, 1998), followed by sporting, cultural and musical events initiated by the mining community when gold was discovered in the mid- to late 1800s. Over the years, much of the tourism development in the region has been attributed to improvements in infrastructure such as rail and sealed roads, allowing visitors access from centers such as Melbourne (Webb and Adams, 1998).

Nowadays, tourism in Alpine Shire is characterized by a diverse range of products, experiences and services that include food and wine, festivals and events, sport, sightseeing, nature and adventure-based activities, touring and four-wheel driving, and historical attractions (ARTB, 2009). Various local actors coalesce to facilitate tourism in the region, including government at various scales – federal, state and local, tourism operators, service providers, regional tourism organizations (RTOs) and committees, chambers of commerce, and neighboring alpine resorts and national parks. Tourism in the Shire is spread across all four seasons of the year but peaks during the summer months. Whilst winter is not identified as a significant tourist season in the valleys, there are four areas within the Shire’s geographical boundaries that are reliant on winter snow-based tourism. These areas include the two alpine resorts of Mount Hotham and Falls Creek, which are managed externally from the Alpine Shire Council by the Alpine Resorts Coordinating Council (ARCC) under state-level jurisdiction. The third is a smaller snow-play recreational area within Mount Buffalo National Park, managed by Parks Victoria, and the fourth and only alpine area entirely within the Shire’s jurisdiction is Dinner Plain Village located just outside Mount Hotham.

Methodology – data collection and analysis

We based our analysis on primary and secondary sources of information in order to construct our description of the social and decision-making processes for tourism in Alpine Shire. Whilst the case study is centered on tourism in Alpine Shire, it is not necessarily bounded by its jurisdiction given that there are valid interests that are non-resident (e.g. stakeholders in neighboring alpine resorts and national parks) and invalid ones within the Shire itself (e.g. individuals promoting a special interest that is incompatible with the common interest of the tourism sector). For these reasons, input was sought from a diverse set of actors such as tourism operators and service providers operating in the Shire, Alpine Shire government leaders, Council officers, chambers of commerce, national park rangers, and alpine resort operators. Following transcription of these interviews, identification of themes and issues of concern were checked and validated through peer-triangulation amongst the authors as well as an informal focus-group session held in August 2008, with a few of the case study respondents.

Through “a vision of beauty and contentment,” the residents of Alpine Shire have documented their vision for their community’s future to 2030 (Alpine Shire Council, 2005). This vision points to the preferred future, and in many ways, these would also influence and underpin the type of destination that would be offered to tourists visiting the region. This formed the basic premise of our initial consultation with relevant tourism actors at Alpine Shire. The aim was to try and identify their main issues of concern particularly with respect to potential and actual barriers to those stated aspirations. Of interest to us was to also ascertain the extent to which climate change and/or climatic factors figured within these concerns, and if so, how.

A number of issues of concern emerged and were identified (see Table 34.1). Through these consultations, we identified the initial framework of widely recognized and on-going issues of concern in this region, and therefore provided confidence that further in-depth analysis would bear insightful, relevant and fruitful information as well as remaining open to ongoing refinement and correction.

Table 34.1 Summary of issues of concern (sourced from Roman, et al., 2010)

Issue of concern |

Description of the issue |

|---|---|

Representation and leadership |

State-level approach to strategic tourism development difficult to engage with locally, consequently affecting branding and marketing efforts as the local scale, functions of the Alpine Region Tourism Board (ARBT) |

Stakeholder relationships |

Socio-political barriers evident amongst major town centers in the Shire, as well as conflicting interests for tourism development with external stakeholders such as local alpine resorts |

Data and statistics |

Lack of consistency in tourist-related data gathering and reporting |

Seasonality and weather variability |

Season-specific tourism offer, drought conditions resulting in water restrictions, observed extremes and shifts in weather patterns and their variability (e.g. bushfire conditions, onset of frosts in autumn) |

Natural disaster management |

Post-disaster recovery and access to support for re-building, as well as the media’s role in the post-disaster recovery process |

Business capacity |

Skills shortage, employability and lack of adequate business skills |

Infrastructure and transport |

Closure of Mt Buffalo Chalet, road signage and tourist attraction signage, touring and public transport options |

Exposure to external factors of macro-scale |

Fluctuations in economic indicators such as the value of the Australian dollar, interest rates, inflation, GDP growth and fuel prices |

Whilst there was some consistency in the way respondents were able to identify and describe the circumstances under which these issues manifest in the Shire, the importance placed on some of these concerns tended to differ depending on geographic or spatial perspective and the actor’s own base values and role in the industry. Table 34.2 summarizes some of these distinct perspectives, with exemplar quotations to clarify on the perspective presented. The table also makes reference and links to the concept of myths as used in policy sciences, to illustrate the usefulness of these categories in distinguishing between special and common interests.

These distinct clusters of values and perspectives were broadly grouped as those belonging to Council members and operators in the Ovens and Kiewa valleys. Interestingly, comparable observations were also reported by Wearing (1981), almost 30 years prior, when the Shires of Bright and Mt. Beauty operated independently. During surveys conducted as part of that earlier study, Wearing (1981: 3) reported that “… the Mt Beauty and Tawonga residents were less inclined to criticize council planning than were the Ovens Valley people.” It was noted that these differences in and range of needs and opinions must be taken into account, despite the fact that no further elaboration was presented as to possible underlying causes. It is clear from this analysis that values and perspectives that underscore a point of view must not be assumed and should therefore be appraised with evidence and procedure, as well as validated for the context they represent.

Yet, the question remains as to how to legitimize those that address the common interest, if that interest can be constructed. As discussed earlier, special interests that are inconsistent with the common interest, as well preconceived solutions that masquerade as problems, are excluded. Comparable to findings in Mattson et al. (2006) and Clark et al. (2008), these results suggest an adaptation problem for the Shire that is embedded in unclear strategic directions, uncertain information, and diverse and strongly felt perspectives among actors. Finding common ground was certainly difficult. However, an approximation to the common interest centered on active engagement to raise the business capacity of all tourism operators in the Shire, allowing Council to better facilitate relations with state authorities in order to mobilize resources and make the sector more resilient in the face of climatic and non-climatic shocks (Roman, 2010).

It is clear from the competing formula espoused by actors in Shire’s tourism sector that a problem can be defined by the mismatch between desired outcomes and current policies and practices. But just as important, the context that makes up this mismatch, the problem, can also insinuate on pathways to adaptation. An analysis of these actors in situ enabled an understanding of behaviors, relationships and developments that contribute to the clarification of the unique context within which the sector operates in Alpine Shire.

Discussion and conclusions

In this chapter, we sought to present insights that center on key methodological and conceptual considerations for how we may use problem-oriented approaches to move forward on adaptation in the context of irreducible uncertainties. We began by first discussing challenges in problem framing and definition when distinct worldviews and values are implicated in a given context, followed by an overview of the main features of the policy sciences approach as a means to structure and navigate through this complexity. This was then followed by a case study of the tourism sector in Alpine Shire, Victoria, Australia, to illustrate this application and harness lessons learned from that experience.

The policy sciences framework was applied as a problem-oriented and integrative approach to explore underlying problems in context and characterize potential barriers to adaptation. As depicted from the case study, experiences with climate as extreme weather-related events were considered to impact upon this community’s ability to develop its tourism industry, however, these experiences were not isolated from a much broader context where non-climatic factors also mattered. The complexity and interaction seen in the types of issues raised provided us with an appreciation for a much broader contextual vulnerability present and the various problem definitions often implicitly articulated by the respondents. However, given the number of problems for adaptability in the tourism sector, the question about how to legitimize those that address the common interest still remains.

An analysis of the myths associated with those issues of concern, and compared against how well they serve the preferred outcome i.e. reducing vulnerability of what is valued, allowed us to distil those concerns that serve a special interest versus that which serves a common interest. Based on our identification of an approximation to the common interest in the Alpine Shire tourism sector, further work involved the presentation of these issues of concern to study participants for correction and refinement and for the development of a comprehensive set of creative policy alternatives that might be explored to resolve the problem (Roman, 2010).

From a methodology perspective, application of the policy sciences has served as a robust framework for structuring the inquiry, as well as understanding and analyzing the empirical data. Admittedly, our experience in defining the problem in the first instance is that it can appear deceptively simple and we concur with Morss (2005) that although it is a crucial key activity defining the problem is also quite analytically challenging and time intensive. Nevertheless, our experience in applying the policy sciences approach has revealed many complex and interacting issues for the Shire’s tourism sector to the challenges of global change. These issues represent more immediate concerns for addressing contextual vulnerability and adaptability, and direct attention to the types of policies and measures that would streamline concrete action towards adaptation and sustainability. Provided these policies are treated as hypotheses to be tested (Lynch, 2009), i.e. appraised through action, it would allow the means towards technical, social and institutional learning for sustainable adaptation.

References

ABS (2009) Cat. No. 3218.0 Regional Population Frowth, Australia 2007–08, Table 2 – Estimated Resident Population, Local Government Areas, Victoria. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Commonwealth of Australia.

Adler, C., McEvoy, D., Chhetri, P. and Kruk, E. (2012) ‘The role of tourism in a changing climate for conservation and development. A problem-oriented study in the Kailash Sacred Landscape, Nepal’, Policy Sciences published online 16 October, 2012. Online. Available HTTP: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11077-012-9168-4# (accessed 5 December 2012).

Alpine Shire Council (2005) Alpine Shire: 2030 Community Vision, Adopted 7 June 2005, Bright: Alpine Shire Council.

ARTB (2009) Alpine Region Tourism Strategic Plan 2009–2011, Adopted February 2009, Alpine Shire, Bright: Alpine Region Tourism Board.

Auer, M.R. (2007) ‘The policy sciences in critical perspective’, in J. Rabin, W. B. Hildreth, and G. Miller (eds) Handbook of Public Administration, New York: CRC Press.

Bardach, E. (1981) ‘Problems of problem definition in policy analysis’, Research in Public Policy & Analysis and Management, 1: 161–171.

Becken, S. and Hay, J.E. (2007) Tourism and Climate Change: Risks and Opportunities, Bristol: Channel View Publications.

Brunner, R.D. (1991) ‘Global climate change: defining the policy problem’, Policy Sciences, 24: 291–311.

Brunner, R.D. (2001) ‘Science and the climate change regime’, Policy Sciences, 34: 1–33.

Brunner, R.D. (2006) ‘A paradigm for practice’, Policy Sciences, 39: 135–167.

Clark, T.W., Willard, A.R. and Cromley, C.M. (2000) Foundations of Natural Resources Policy and Management, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Clark, D.A., Lee, D.S., Freeman, M.M.R. and Clark, S.G. (2008) ‘Polar bear conservation in Canada: Denning the policy problems’, Arctic, 61: 347–360.

Creswell, J.W. (2007) Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, second ed, Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

de Chazal, J., Quétier, F., Lavorel, S. and van Doorn, A. (2008) ‘Including multiple differing stakeholder values into vulnerability assessments of socio-ecological systems’, Global Environmental Change, 18: 508–520.

de Leon, P. (1994) ‘Reinventing the policy sciences: Three steps back to the future’, Policy Sciences, 27: 77–95.

de Leon, P. and Vogenbeck, D.M. (2007) ‘Back to square one: the history and promise of the policy sciences’, in J. Rabin, W. Hildreth, and G. Miller (eds) Handbook of Public Administration, New York: CRC Press.

DPCD (2007) Local Government Victoria: Alpine Shire: Department of Planning and Community Development, State Government of Victoria.

Dwyer, L., Edwards, D., Mistilis, N., Roman, C. and Scott, N. (2009) ‘Destination and enterprise management for a tourism future’, Tourism Management, 30: 63–74.

Hennessy, K., Wheatton, P., Smith, I., Bathols, J., Hutchinson, M. and Sharples, J. (2003) The Impact of Climate Change on Snow Conditions in Mainland Australia, Australia: CSIRO Atmospheric Research & CERES.

Hytten, K. (1994) Pragmatism, Postmodernism and Education, Annual Meeting of the American Educational Studies Association, 13 November, Chapel Hill, NC.

Kelly, P.M. and Adger, W.N. (2000) ‘Theory and practice in assessing vulnerability to climatic change and facilitating adaptation’, Climatic Change, 47: 325–352.

Lasswell, H. (1971) A Pre-View of Policy Sciences, New York: Elsevier.

Lasswell, H. and Kaplan, A. (1950) Power and Society, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Lasswell, H. and McDougal, M. (1992) Jurisprudence for a Free Society: Studies in Law, Science, and Policy, The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Lynch, A.H. (2009) ‘Adaptive governance: how and why does government policy change?’ ECOS Magazine, 146: 31.

Lynch, A. and Brunner, R. (2007) ‘Context and climate change: an integrated assessment for Barrow, Alaska’, Climatic Change, 82: 93–111.

Lynch, A.H., Tryhorn, L. and Abramson, R. (2008) ‘Working at the boundary: facilitating interdisciplinarity in climate change adaptation research’, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 89: 169–179.

Mattson, D., Byrd, K., Rutherford, M., Brown, S. and Clark, T. (2006) ‘Finding common ground in large carnivore conservation: mapping contending perspectives’, Environmental Science and Policy, 9: 392–405.

Max-Neef, M.A. (2005) ‘Foundations of transdisciplinarity’, Ecological Economics, 53: 5–16.

Morss, R.E. (2005) ‘Problem definition in atmospheric science public policy: the example of observing system design for weather prediction’, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 86: 181–191.

O’Brien, K. (2009) ‘Do values subjectively define the limits to climate change adaptation?’, in W.N. Adger, I. Lorenzoni, and K. O’Brien (eds) Adapting to Climate Change: Thresholds, Values, Governance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O’Brien, K.L. and Wolf, J. (2010) ‘A values-based approach to vulnerability and adaptation to climate change’, Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 1: 232–242.

O’Brien, K., Eriksen, S., Nygaard, L.P. and Schjolden, A. (2007) ‘Why different interpretations of vulnerability matter in climate change discourses’, Climate Policy, 7: 73–88.

Patt, A.G. (2009) ‘Learning to crawl: how to use seasonal climate forecasts to build adaptive capacity’ in W.N. Adger, I. Lorenzoni, and K. O’Brien (eds) Adapting to Climate Change: Thresholds, Values, Governance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pickering, C., Good, R. and Green, K. (2004) Potential Effects of Global Warming on the Biota of the Australian Alps, Report to the Australian Greenhouse Office, Canberra.

Roman, C.E. (2010) On Being Adaptable: Transformative Lessons on Adaptation Through Problem-orientation. A Case of the Tourism Sector in Alpine Shire, Victoria, Australia, Melbourne: School of Geography and Environmental Science, Monash University.

Roman, C.E., Lynch, A.H. and Dominey-Howes, D. (2010) ‘Uncovering the essence of the climate change adaptation problem – a case study of the tourism sector at Alpine Shire, Victoria, Australia’, Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 7: 237–252.

Roman, C.E., Lynch, A.H., and Dominey-Howes, D. (2011) What is the goal? Framing the climate change adaptation question through a problem-oriented approach’, Weather Climate and Society, 3: 16–30.

Schröter, D., Polsky, C. and Patt, A.G. (2005) ‘Assessing vulnerabilities to the effects of global change: an eight step approach’, Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 10: 573–595.

Tryhorn, L. (2008) An integrated assessment of flooding vulnerabilities in the Alpine Shire of Victoria, Australia, unpublished PhD thesis, School of Geography and Environmental Science, Monash University, Melbourne.

Wearing, R.J. (1981) ‘Tourism: blessing for bright? The impact of tourism on a small community and its planning processes’, in Australian Institute of Urban Studies, La Trobe University (eds), Canberra: Paragon Printers.

Webb, D. and Adams, B. (1998) The Mount Buffalo Story, 1898–1998, Melbourne: The Miegunyah & Melbourne University Press.

Worboys, G.L. and Pickering, C.M. (2002) Managing the Kosciouszko Alpine Area Conservation Milestones and Future Challenges, CRC for Sustainable Tourism Pty Ltd, Mountain Tourism Research Report Series: No. 3. Gold Coast.