30 Social network actors and novel information for adaptive capacity

Introduction

Social network theory (SNT) and social network analysis are used in this chapter as a theoretical frame to examine how social networks function and if/how community members share information within the networks that then facilitate their coping or adaptive capacity to climate vulnerability. SNT has been used to interpret human relationships through nodes and ties, where a node is the individual actor in the network and ties are the relationships between the actors. Together with social network analysis, the theory has been applied to map human connections, patterns of communications, and their implications (Barnes, 1954; Granovetter, 1973; Rogers, 1986; Wasserman and Faust, 1994; Haythornthwaite, 1996).

Mark Granovetter´s Theory of the Strength of Weak Ties (1973) anchored the notion that most innovative or novel information comes from weak ties or bridging ties that connect two disparate groups. Expanding on Granovetter’s theory, Ronald Burt (2004, 2005) established that network brokers are those who create the bridging ties between groups and that brokers have access to information which leads to competitive advantages for groups to develop new or novel ideas for change (2004, 2005). In the context of human adaptation to environmental dimensions of change or climate related impacts (such as extreme and unexpected flooding) these theoretical foundations allow two key questions to be posed: Do brokers inside and outside community networks provide innovative information or knowledge that villagers use to adopt short-term coping, and/or long-term adaptive strategies to climate stresses? Are there other network actors that are important in group innovation? Social network theory provides a frame to discover who provides innovative knowledge and whether communication methods change during different weather events. The field data presented in this chapter addresses these questions while also examining the attributes of different network actors.1

Theoretical framework

Social network theorists have shown that within industries, villages, regions, and administrative units, people often specialize their roles in groups or clusters to create advantages for individual or group change (Barnes, 1954; Granovetter, 1973; Rogers, 1986; Burt, 2004; Wasserman and Faust, 1994; Haythornthwaite, 1996; Putnam, 2000; Borgatti, 2003). How knowledge is transferred among network members has been shown in violent gang networks (Grann, 2011), natural resource management structures (Crona and Bodin, 2006), social-ecological systems and adaptive governance (Olsson et al., 2006), water resource management (Adger, 2003; Olsson, et al., 2004); and student social movements (Gladwell, 2010). Olsson and colleagues (2004) provide evidence that key leaders can create opportunities to assist resource users in adaptive resource governance, and that leadership and networks are needed for successful transformations in social-ecological systems. There is also data to support that groups integrate and build knowledge through brokers who create bridges across the groups (Krishna, 2002; Burt, 2005). Fernandez and Gould (1994) exemplified how brokers can mediate flows of information between two disparate actors or groups and thus wield influence. Brokers within social networks have been shown to play a role in interactions between investment bankers, between real estate agents, and in small business transactions where the internal networks were strongest combined with someone who brokered deals outside of the group (Burt, 2005).

Granovetter’s Theory of the Strength of Weak Ties focuses on the cohesiveness of the ties one person has to another, and theorizes that most novel information is devised from liaison actors who have weak and bridging ties that connect two networks or groups together. These individuals are ‘best placed to diffuse […] innovation’ (Granovetter, 1973: 1367). Granovetter argues that we know little about interactions within small groups and how they aggregate to form larger patterns (1973: 1360), yet these small interactions are important for sharing knowledge and information, as well as for community social cohesion. If one views climate change adaptation as adjustments in group behavior for the purpose of reducing vulnerabilities to climate related impacts, then brokers who provide this novel information that spurs either autonomous or planned actions can serve as agents to enhance community adaptive capacity. Brokers can not only transfer crucial information between groups, but they are able “to see how a belief or practice in one group could create value” in another group (Burt, 2004: 355). These network actors have a competitive advantage in that they are able to see good ideas by being on the network periphery. “What matters is the value produced by the idea, whatever the source.” People with connections across structural holes have early access to diverse information “which gives them a competitive advantage in seeing and developing good ideas” (Burt, 2004: 388). Entrepreneurial and innovative opportunities in networks are created by brokers, whether they serve as a liaison, representative, gatekeeper, or coordinator who brings about change (Fernandez and Gould, 1989; Burt, 2000: 12). In understanding more fully who communicates information (and what attributes they possess) in community level social networks, what information is communicated, and how the information leads to change, learning can be garnered about how communities cope and adapt to climate variability.

A social network is defined here as a group of individuals that form a constellation of relationships (Magsino, 2009). Actors within networks include key individuals, brokers, and members. A key individual is a person who has stature within the social network and is viewed as influential (through formal or informal means) by other network members. A broker is a network actor who creates bridges that link one group to another group. The bridge is the method by which the broker shuttles information or knowledge between two groups or networks. Bridges help to facilitate communication and encourage innovation. A formal broker is a person who is a part of the main social network, while an informal broker is positioned outside the main network, but someone who possesses information that can be useful to members in the main network. Members are individuals in the network, in this case, the village members.

Climate change impacts include social, spatial and temporal risks that lead to various coping and adaptive methods and practices, including livelihood diversification, migration, pooling of resources, and use of social networks to share risk (Agrawal and Perrin, 2009: 355, 449). Adaptation is viewed here as a dynamic process that involves multiple actors in society, and as a wide array of strategies that individuals, communities or groups employ when faced with hazards or vulnerabilities (IPCC, 2007). Adaptive capacity is viewed as the ability of groups to adjust to extreme events or stresses, to moderate potential damages (IPCC, 2007), and to manage risks and impacts through the development of new knowledge and effective approaches. Social networks are one mechanism through which communities harness or mobilize their adaptive capacity, and new knowledge development within social networks can lead to innovative tools for coping with climate impacts.

Data from a Bangladeshi village provides useful insights about how a rural social network is composed; who plays which role in the network, what attributes the actors display, and that network actors are potentially important agents in coping and adaptive capacity.

Methods

Bangladesh is one country that will very likely suffer severe climate impacts in the future. Projected impacts will exacerbate the current natural hazards that affect Bangladesh today. The country will witness more frequent and severe tropical cyclones; heavier and more erratic rainfall in some areas and decreased rainfall in others; warmer and more humid weather; and sea level rise (Bangladesh Ministry of Environment and Forests 2008: 13). Several of these impacts will lead to higher river flows, an increase in riverbank erosion and increased sedimentation in riverbeds, affecting the agriculturally dependent population, and further challenging their coping mechanisms and adaptive capacities. The 2005 Bangladesh National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA) lays out the Bangladesh governmental plan for the support of local and national future adaptation mechanisms to reduce adverse effects of climate change. One of the planned adaptation strategies suggested in the NAPA is to disseminate adaptation information to vulnerable communities for emergency preparedness measures and awareness raising (Ministry of Environment and Forest Government, 2005: xvi). This strategy indicates that social networks and their actors could serve as sources of information, as well as dissemination mechanisms to affected groups.

Social network data was collected during 2008 and 2009, during both the wet and dry seasons in the village of Tartapara, Bangladesh. Methods employed include focus group interviews (three groups of 25–30 villagers), in-depth interviews (eight interviews with identified key individuals) and 15 household questionnaires. These tools were used to collect social network data and attribute data characterizing the network actors; to map who acts as a broker within the social network; assess the role of bridges and linkages within the village and other linked networks and organizations; and to identify the key individuals and brokers who villagers turn to both during a climatic event and during non-event periods. Interviews were conducted in Bangla, through an interpreter, and questionnaires were translated from English to Bangla and answered by household members with the assistance of the translator.

Results

Tartapara is located in Jamalpur District, 180 km from Dhaka, on the edge of the Brahmaputra River (locally referred to as the Jamuna River) and is composed of approximately 400 households, and 2,200 people. Roofs are often made of dried grass and leaves, while some homes have corrugated iron roofs. The literacy level of the population is 8 percent. Employed villagers work as day laborers both in Tartapara and nearby villages, and in seasonal agriculture. Those who do possess assets own their houses and/or cattle, hens or goats. Several female villagers described cattle as precious and wealth determining as they served as a risk covering asset that they could sell “at any crisis moment” (Focus group 1, 2008) such as during a flood. Infrastructure around and within Tartapara is extremely limited, and during the rainy months, a boat is often used as transport to and from the village. The Jamuna River creates much lateral erosion and river flooding from June to September, and in Tartapara, villagers reported that the river “had split itself ” (Focus group 1, 2008) creating two major rivers around small swathes of land.

The villagers are primarily focused on securing their next meal and planning the next crop, or obtaining a small loan. Annual floods are a fact of life for them, having learned to cope with and respond to annual floods as a natural process (Huq, 2009; Rahman, 2009). However, a widely held view among villagers was that the Jamuna River is “more dangerous” now and that it “can kill”: Floods are “unpredictable now” and are occurring more frequently (Focus groups 1 and 2, 2008). For example, villagers spoke about experiencing severe floods two to three times per year (as in 2007). In the past, the villagers expected an annual flood and prepared for it like their ancestors: “We watch the ants!” (Elected Member B interview, 2008). One of the village elders explained that for as long as he can remember, they have relied on the ants to indicate when it is time to move the houses to higher ground. The ants moved their houses up to safety and the villagers followed, just as far as the ants had relocated. Villagers can no longer solely rely on the ants, because the floods come “with no warning” and more often. As one villager said, “we can be flooded at any time of night!” (Elected Member B interview, 2008).

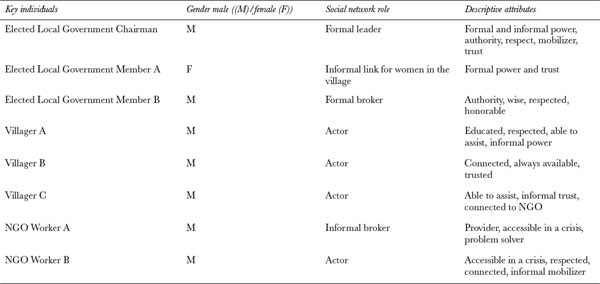

Focus group discussions revealed eight key individuals who were identified by the villagers as the people who they depended on before, during, and after flood periods. Follow up in- depth interviews garnered information about attributes and qualities of the key individuals, and what motivates the linkages within the village network, as exhibited in Table 30.1. Interview findings indicated that the Elected Local Government Chairman (Chairman) and Elected Local Government Member B (described as the Matabbar in Bangla, meaning Social Leader) were the key individuals who served as the formal leader and the formal broker, respectively, within the social network. Elected Local Government Member B (Elected Member B) is described as an “honorable wise leader” by other villagers (Focus groups 1, 2, and 3, 2008; in depth interview Elected Government Member B, 2009) in part perhaps because of his age (68 years) and because he is an elected member of the Union Parishad.2

Elected Government Member A (Elected Member A), the only female key individual, served as the main contact for the other female members of the community. Informally, the women gather at the evening market to discuss concerns. If there is an issue that the women feel is not being addressed by the Chairman (for example, they wished to press the Chairman to request governmental authorities to build a dam up river) they voice their concerns through Elected Member A. Elected Member A, in turn, communicated directly to Elected Member B, who then communicated with the Chairman.

All of the interviewees agreed that the formal leadership in the village rests with the Chairman. They also agreed that non-governmental organization (NGO) Worker A serves as an informal broker who creates a bridge for flow of information and employment opportunities. NGO Worker A is informally linked to the network during both dry and wet seasons. During the dry season, he explained, he can reach the 150 villagers in his programme3 directly, but during

a natural disaster or flood, I contact the local government leader (Chairman) and social leader (Elected Member B) in the village, as during flood time they make the decision as to what the community needs most … because of their power, we keep in contact with them.

(In-depth interview, NGO Worker A, 2009)

In-depth interviews with the eight key individuals revealed that honesty (five mentions), acceptance by others (four mentions), and trust (four mentions) were cited most frequently as those leadership qualities that key individuals valued most. When asked how leadership is exhibited in Tartapara, “informal” was used by all of the respondents, both in describing the leaders and the leadership structure. The interviewee responses about the key individual attributes indicate that authority, trust, and accessibility in a crisis appear to be important for brokers to possess for villagers to turn to them when in need, as evidenced in Table 30.1.

Interviews and questionnaires, and consultations with village members, allowed the author to outline the functioning social network of Tartapara during wet and dry seasons, as depicted in Figure 30.1, and shows that the Tartapara villagers are connected to the Chairman (the formal leader), through the Elected Member B (the formal broker). The direct link between the villagers and these two individuals are indicated by a solid line. The villagers are also informally linked to NGO Worker A (informal broker), as shown by a dashed line. In turn, NGO Worker A is connected to the Chairman, as shown by the broken line. Lastly, the entire network is loosely linked to NGO Worker A’s own NGO network, as indicated by the dotted line.

Figure 30.2 depicts the Tartapara network during a “hothat ban” scenario, or when a sudden flood impacts the village, and indicates that the brokers have limited roles during this scenario. Figure 30.2 also introduces the presence of “spontaneous young leaders” who are young, strong men in the community, described by the other villagers as those who saved the community from literally falling into the river during a sudden flood.

Villagers described communication and the action steps that the community follows during both seasons. Table 30.2 depicts these steps, and an additional set of steps followed when the floods “come suddenly” (hothat ban), during the wet season. Before 2006, villagers explained that Tartapara witnessed annual, predictable “water rising for three days or so” (Focus Groups 1, 2, and 3, 2008) that forced villagers to relocate and resettle. All respondents reported that they had relocated at least once, either with the entire village, or from another village. Many members talked about having relocated three or more times. In 2007, however, sudden floods began (and continued to occur in 2008 and 2009); occurring in both late June and then again in mid-July. The latter persisted for over two weeks, rather than a few days: villagers then realized they could no longer rely on floods to be predictable. Instead, they had to be ready to act at any time. The data here presents information from three years, making it impossible to know whether reactive adaptive measures will be become more formalized amongst the villages in future years. It can be suggested, however, that sudden floods will become increasingly likely with climate change.

I. Wet season |

II. Dry season |

III. Wet season hothat ban scenario |

|---|---|---|

1 Villagers are warned by megaphones or radio by local agencies that the river is likely to flood. |

1 The villagers talk amongst themselves about a concern, for example, their desire to build a dam up river. |

1 No warning that the river is likely to flood. |

2 Elected Member B and the Chairman mobilize the network: They organize the villagers to move to the river embankment and to shelters for temporary resettlement. |

2 The villagers approach Elected Member B, as the social leader, to express their concern. They ask Elected Member B to approach the Chairman with their concerns, depending on the topic. |

2 When the water encroaches on the village, the villagers organize themselves to relocate. |

3 After the flood recedes, the Chairman manages the resettled community; which includes tending to new needs and providing linkages with outside agencies. For example, the village often finds shelter in a school building close by. The Chairman has direct communication with the school authorities and arranges for school to be suspended and formally appropriated by the villagers for use as a shelter for a period of time. |

3 Elected Member B approaches the Chairman, and acts as a broker of information between the villagers and the Chairman. NGO Worker A contacts villagers on a daily basis, providing them with an opportunity for daily labor, as well as longer-term economic development options. He provides them with information from his own network outside the village. |

3 The network between Elected Member B and the Chairman has no time mobilize. Spontaneous young leaders work to save the villagers and their possessions. People try first to rescue their family and assets, and then they turn to assist others. After rescuing others, the villagers regroup at a shelter. |

4 The Chairman renders a decision on which action will be taken in the village. |

4 After the village resettles, and only after the resettlement, the network between Elected Member B and the Chairman sets itself in motion. |

Discussion and conclusion

Data about the personality attributes of the social network actors in Tartapara, as depicted in Table 30.1, indicate that Elected Local Government Member B was described in terms such as “authority, wise, respected, and honorable,” while NGO Worker A was described as a “provider, accessible in a crisis, and problem solver.” These descriptions indicate that there are no distinctive overlaps between the attributes of these two brokers, providing no conclusive information about which types of people serve best as bridging brokers (Burt, 2005). More data in similar settings needs to be gathered to clarify which attributes effective brokers possess and that are most important for the diffusion of innovative information. Respect, trust and accessibility during a crisis, however, were important attributes for key network actors to possess, not only the brokers. The change in network structure presented in Figure 30.2 indicates that communication methods and network structure do change during unpredictable floods. The social network structure breaks apart and roles change. Both the formal and informal brokers are pushed to the periphery of, or completely outside, the network. Instead, the young spontaneous leaders in this community play a distinctive role during sudden flood events, working to save the community members. The young leaders’ relationship ties and attributes need to be further studied to understand if they too act as brokers (during certain unpredictable climatic events) whose linkages help to diffuse innovative information to the other networks actors in the village. To date, data has not been gathered from these actors about their knowledge and methods of information diffusion to other villagers: We do not yet know what long-term effect the young leaders have on the strength of ties within the network or on long-term adaptation in the community, however they appear to play an important role in community coping during unpredictable natural events. These young leaders should also be drawn upon when devising future development and adaptation policies as they most likely have important knowledge for local innovation and change.

Table 30.2 exemplifies not only steps that the village network actors follow but also illuminates how brokers and the mobilizer share information and knowledge between networks and among network actors. For example, NGO Worker A has the benefit of not only being on the periphery of the network, but he is connected to his professional external network that provides an avenue for innovative ideas. This network actor spoke about the importance of having “loose linkages” to the village network between the village Chairman, the village elder, the villagers, and of not “disturbing the formalities” (in-depth interview, NGO Worker A, 2009) of the village network, indicating that his connections to the formal network were weak, yet important to the daily lives of the villagers. Elected Local Government Member B has the advantage of having strong ties to various smaller groups within the community and thus serves as a broker who approaches the Chairman with ideas/concerns from other community members. Elected Local Government Member B also shuttles and interprets information and decisions from the Chairman back to the villagers.

The theoretical frame presented here (Granovetter, 1973; Burt, 2005) suggests that the combination of Elected Local Government Member B’s linkages to the villagers and the Chairman, coupled with the weak linkages from the NGO Worker A, could lead to the creation of new and innovative knowledge that could in turn lead to the development of group adaptive actions. However, from the data collected to date in Tartapara, one cannot conclude that it is these linkages that lead directly to adaptive action. The theory maintains that network brokers have a competitive advantage (Burt, 2004) in that they have access to diverse information which leads to new ideas and strategies: NGO Worker A’s weak ties to the network enhances his ability to provide innovative knowledge (Burt, 2005) to the village network actors for the benefit of short-term coping and potentially long-term adaptive capacity. The Chairman and the brokers potentially facilitate action as they use their positions to provide necessary leadership and organizational management during flood times, while they also enable a communication structure where new knowledge for innovative change can be exchanged. They provide the framework for villagers to communicate, mobilize and voice concerns, and they create a link to local organizations and attend to the various and changing needs of villagers.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible by a grant from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida). Tartapara network data presented here was derived from: Rotberg, F. (2010) ‘Social networks and adaptation in rural Bangladesh’, Climate and Development, 2: 65–72.

1 Burt offers the theory that a gap in the theoretical discussion surrounds the idea of who becomes a broker, and what general attributes brokers possess that helps them lead others towards change. Burt argues that attribute data need to be collected to understand and to assess whether a broker is more effective if he/she engages in informal or formal relationships between the different groups (2005: 28, 50).

2 There are three levels of local government in Bangladesh: 1) Upazila (Sub-District), 2) Union Parishad (City Council) and 3) Village Council. All of those serving on these levels are directly elected by public vote, for a term of five years. The Elected Local Government Chairman and the two members referenced in Table 30.1 are elected by the people to the local Union Parishad, or City Council. The City Council is composed of one Chairman and nine members.

3 The program was focused on “eco development,” where the villagers were provided with day labor opportunities, such as helping to build a government road, or longer-term loan options, providing them with the ability to purchase animals. Villagers were also exposed to training and capacity building programs.

References

Adger, W.N. (2003) ‘Social capital, collective action and adaptation to climate change’, Economic Geography, 79 (4): 387–404.

Agrawal, A. and Perrin N. (2009) ‘Climate adaptation, local institutions, and rural livelihoods’, in N. Adger, I. Lorenzoni, and K. O’Brien (eds) Adapting to Climate Change, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bangladesh Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh (2008) ‘Bangladesh climate change strategy and action plan 2008’, Dhaka: Ministry of Environment and Forests.

Barnes, J. (1954) ‘Class and committees in a Norwegian Island Parish’, Human Relations, 7: 39–58.

Borgatti, S. P. (2003) ‘The key player problem’, in R. Breiger, K. Carley and P. Pattison (eds) Dynamic Social Network Modelling and Analysis: Workshop Summary and Papers, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Burt, R. (2000) ‘The network structure of social capital’, in R. Sutton, R. and B. Staw (eds) Research in Organizational Behaviour, 22, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Burt, R. (2004) ‘Structural holes and good ideas’, American Journal of Sociology, 110 (2): 349–399.

Burt, R. (2005) Brokerage and Closure: An Introduction to Social Capital, New York: Oxford University Press.

Crona, B. and Bodin, O. (2006) ‘What you know is who you know? Communication patterns among resource users as a prerequisite for co management’, Ecology and Society, 11 (2): 7–40.

Elected Member Government Member B (2009) Personal interview, Tartapara, Bangladesh.

Focus Group 1 (2008) Village of Tartapara, Bangladesh.

Focus Group 2 (2008) Village of Tartapara, Bangladesh.

Focus Group 3 (2008) Village of Tartapara, Bangladesh.

Gladwell, M. (2010) ‘Small change’, The New Yorker, October 4: 42–49.

Grann, D. (2011) A murder foretold, The New Yorker, April 4: 2–61.

Fernandez, R. and Gould, R. (1994) ‘A dilemma of state power: brokerage and influence in the natural health policy domain’, American Journal of Sociology, 99 (6): 1455–1491.

Granovetter, M. (1973) ‘The strength of weak ties’, American Journal of Sociology, 78 (6): 1360–1380.

Haythornthwaite, C. (1996) ‘Social network analysis: an approach and technique for the study of information exchange’, Library and Information Science Research, 18: 323–342.

Haythornthwaite, C. (1998) ‘A social network study of the growth of community among distance learners’, Information Research, 4 (1).

Huq, S. (2009) International Institute for Environment and Development, personal communication, Dhaka, Bangladesh, February.

IPCC (2007) ‘Summary for policymakers’, in M.L. Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson (eds) Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Krishna. A. (2002) Active Social Capital. Tracing the Roots of Development and Democracy, New York: Columbia University Press.

Magsino, S. (2009) Applications of Social Network Analysis for Building Community Disaster Resilience, Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Ministry of Environment and Forest Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh (2005) National Adaptation Programme of Action, Final Report, November.

NGO Worker A (2009) Personal interview, Tartapara, Bangladesh.

Olsson, P., Folke, C. and Hahn, T. (2004) ‘Social-ecological transformation for ecosystem management: The development of adaptive co-management of a wetland landscape in Southern Sweden’, Ecology and Society, 9 (4): 2–26.

Olsson, P., Gunderson, L., Carpenter, S., Ryan, P., Lebel, L., Folke, C. and Holling, C.S. (2006) ‘Shooting the rapids: Navigating transitions to adaptive governance of socioecological systems’, Ecology and Society, 11 (1): 18–39.

Putnam, R. (2000) Bowling Alone, New York: Simon and Schuster.

Rahman, A., Bangladesh Centre for Advanced Studies. Personal Communication, Dhaka, Bangladesh, April 2008 and February 2009.

Rogers, E.M. (1986) Communication Technology: The New Media in Society, New York: Free Press.

Smit, B. and Wandel, J. (2006) ‘Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability’, Global Environmental Change, 16: 282–292.

Wasserman, S. and Faust, K. (1994) Social Network Analysis, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.