Ronald F. Ries, CPA

American Express Tax and Business Services, Inc.

Ian J. Benjamin, CPA

American Express Tax and Business Services, Inc.

The authors wish to acknowledge that the exhibits and inspiration for this work were derived from the work Financial and Accounting Guide for Not-for-Profit Organizations, Fifth Edition, by Price Waterhouse LLP, Malvern J. Gross Jr., Richard F. Larkin, Roger S. Bruttomesso, and John J. McNally (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1995).

Not-for-profit organizations range from the large and complex to the small and simple. They include hospitals, colleges and universities, voluntary social service organizations, religious organizations, associations, foundations, and cultural institutions. All are confronted with accounting and reporting challenges. All are presently covered by authoritative accounting literature. This chapter discusses not-for-profit accounting and reporting conventions and examines accounting pronouncements, auditing concerns, and the regulatory environment applicable to different types of not-for-profit organizations. Health care organizations are covered in Chapter 36.

As this latest edition of the Handbook goes to press, there are many issues within our community, including the accounting environment, which requires all organizations, including not-for-profits, to adhere to accounting policies and principles with the utmost due diligence required to satisfy a scrutinizing public and government regulators.

Not-for-profit accounting has undergone a period of profound change. In the recent past, authoritative accounting principles and reporting practices were established for many not-for-profit organizations that previously had neither.

In 1972, the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) issued an Industry Audit Guide for hospitals. In 1973, an Industry Audit Guide for colleges and universities was issued. And in 1974, a third not-for-profit Industry Audit Guide, for voluntary health and welfare organizations, was issued. In 1990, the AICPA issued a new audit and accounting guide, "Audits of Providers of Health Care Service," to replace the 1972 hospital audit guide.

In late 1978, the AICPA issued Statement of Position (SOP 78-10), "Accounting Principles and Reporting Practices for Certain Nonprofit Organizations." SOP 78-10 defines accounting principles and reporting practices for all not-for-profit organizations not covered by earlier guides.

For several years, as the most current broad-scope pronouncement of the accounting profession on not-for-profit accounting, the SOP was the authoritative reference for not-for-profit accounting and reporting questions for the organizations covered, and it was consulted for guidance by other organizations on questions not addressed in their respective audit guides.

These guides and the SOP had a dramatic effect on not-for-profit accounting, as they represented the first authoritative attempt to codify accounting principles and reporting practices for the not-for-profit industry. However, inconsistencies existed among the four guides, and they frequently contradicted one another on key accounting concepts. Also, the accounting principles presented in the guides had limited authority as they constituted Generally Accepted Accounting Procedures (GAAP) only until formal standards were set on this subject by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB).

By the early 1980s, persons interested in not-for-profit accounting issues had identified the following key areas of accounting that would have to be considered in unifying the diverse not-for-profit accounting practices:

Reporting entity (when controlled and affiliated organizations should be included in an entity's financial statements)

Depreciation

Joint costs of multipurpose activities, particularly those involving a fund-raising appeal (on what basis such costs should be divided among the various purposes served)

Revenue recognition for expendable/restricted receipts (when, in which fund, and how such items should be reported as revenue)

Display (what format should be used to present financial data)

Valuation of investments

Contributions (how these should be valued, when and how they should be reported)

Grants awarded to others (when these should be accrued and expensed by the grantor)

Before accounting principles could be written, concepts had to be developed. The FASB had originally excluded not-for-profits from concepts development, but later started a separate project for not-for-profits. The first concepts statement under this project was issued in 1980. SFACNo. 4, "Objectives of Financial Reporting by Nonbusiness Organizations," proved to be so similar to the corresponding statement for businesses (SFAC No. 1) that the FASB started thinking in terms of only one set of concepts. Indeed, SFAC No. 2 was amended to include not-for-profits; SFAC No. 6, "Elements of Financial Statements" covers both types of entities, although some parts of this statement deal separately with the two sectors.

The FASB identified five areas in which it planned to develop accounting principles for not-for-profits: depreciation, contributions, the reporting entity, financial statement display, and investments, and has issued the following standards that have revolutionized not-for-profit accounting.

Depreciation is the subject of SFAS No. 93. Effective in 1990, this requires all not-for-profits to depreciate long-lived tangible assets, except that museum collections and similar assets often considered to be inexhaustible need not be depreciated if verifiable evidence of their inexhaustibility is available.

Accounting for contributions received and made and for museum collections is the subject of FASB Statement No. 116, effective beginning in 1995. Upon adoption it requires a number of significant changes to accounting practices previously followed by many not-for-profit organizations. It requires immediate revenue recognition for all unconditional gifts and pledges, regardless of the presence of donor restrictions and regardless of the intended period of payment (pledges payable in future periods will be discounted to Present Value (PV). Donors will follow a similar policy for recording expenses and liabilities. Donated services of volunteers will be recorded by charities if certain criteria are met. Museum collection items will be capitalized unless certain criteria are met.

The requirement for immediate recognition of revenue for purpose and time restricted gifts results from FASB's conclusion in SFAC No. 6 that unspent expendable restricted gifts do not normally meet the definition of a liability (deferred revenue).

Financial statement format was initially the subject of initial work by an AICPA task force. FASB issued a statement of financial accounting standards No. 117 on financial statement format in June 1993. It became effective in 1995, at the same time as the new standard on contributions (previous bullet).

In 1995, the FASB issued SFAS No. 124, "Accounting for Certain Investments Held by Not-for-Profit Organizations." Briefly, its requirements are that all marketable securities be reported at current value in the balance sheet, and that unrealized losses be reported in the unrestricted class of net assets (absent donor restrictions or law which would require reporting losses in a restricted class). A more detailed summary of this standard is at Section 35.2(i).

In 1999, the FASB issued SFAS No. 136, "Transfers of Assets to a Not-for-Profit Organization or Charitable Trust that Raises or Holds Contributions for Others." It differentiates situations in which not-for-profit organizations act as agents, trustee, or intermediaries from situations in which not-for-profit organizations act as donors and donees. It also indicates how organizations that act as agents, trustees, or intermediaries are to report receipts and disbursements of assets if those transfers are not its contributions as defined in SFAS No. 116 and how a beneficiary is to report its rights to the assets held by a recipient organization.

Both Statements were issued in June 1993. They were effective for fiscal years beginning after December 15, 1994 (e.g., for a June 30 year-end entity, for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1996). Adoption of No. 117 must be made retroactively; adoption of No. 116 can be made either retroactively or prospectively. Copies are available from the FASB Order Department: P.O. Box 5116, Norwalk, CT 06856.

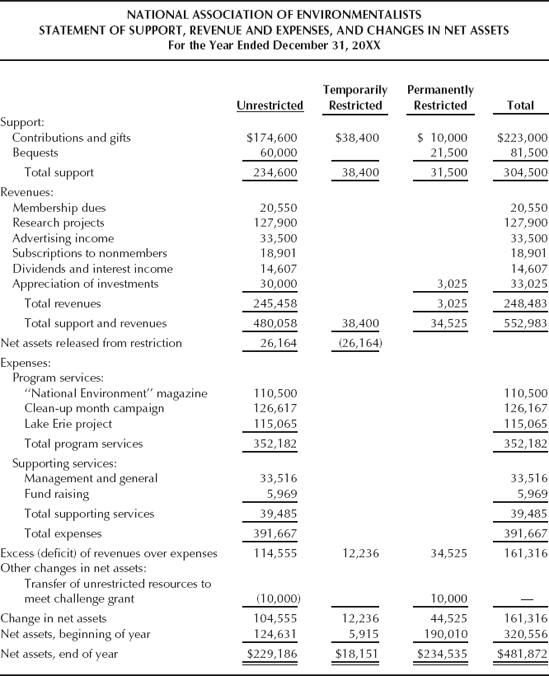

Statement No. 117 requires organizations to present aggregated financial data: total assets, liabilities, net assets (fund balances), and change in net assets. Some not-for-profits already do, but many have not done this in the past. Organizations are free to present data disaggregated by classes of net assets (corresponding to funds), but, except for donor-restricted revenue, net assets, and change in net assets, no detail by class is explicitly required.

Three classes of net assets are defined: unrestricted, temporarily restricted, and permanently restricted. Net assets of the two restricted classes are created only by donor-imposed restrictions on their use. All other net assets, including board-designated or appropriated amounts, are legally unrestricted, and must be reported as part of the unrestricted class, although they may be separately identified within that class as designated if the organization wishes.

Permanently restricted net assets will consist mainly of amounts restricted by donors as permanent endowment. Some organizations may also have certain capital assets on which donors have placed perpetual restrictions. Temporarily restricted net assets will often contain a number of different types of donor-restricted amounts: unspent purpose-restricted expendable gifts for operating purposes, pledges payable in future periods, unspent explicitly time-restricted gifts, unspent amounts restricted for the acquisition of capital assets, certain capital assets, unmatured annuity and life income funds, and term endowments.

One requirement that is a significant change for many organizations is the reporting of all expenses in the unrestricted class, regardless of the source of the financing of the expenses. As expendable restricted revenue will be reported in the temporarily restricted class, when these amounts are spent, a reclassification (transfer) will be made to match the restricted revenue with the unrestricted expenses.

A second requirement is that all capital gains or losses on investments and other assets or liabilities will be reported in the unrestricted class, no matter which class holds the underlying assets/liabilities, unless there are explicit donor restrictions, or applicable law, which require the reporting of some or all of the capital gains/losses in a restricted class. This practice will often have the effect of increasing the reported unrestricted net asset balance (and decreasing the other net asset balances), compared with previous reporting principles.

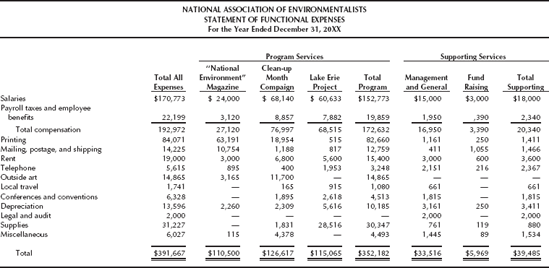

All organizations must report expenses by functional categories (program, management, fund-raising). Voluntary health and welfare organizations must also report expenses by natural categories (salaries, rent, travel, etc.) in a matrix format; other organizations are encouraged to do so. Reporting in functional categories is new for some organizations, mainly those that do not raise significant amounts of contributions from the general public, such as trade associations, country clubs, and many local churches.

A new financial statement for many organizations is a statement of cash flows, showing where the organization received and spent its cash. Cash flows will be reported in three categories: operating flows, financing flows (including receipt of nonexpendable contributions), and investing flows. This statement has been required for businesses for several years by SFAS No. 95, which should be consulted for further information.

Statement No. 95 permits either of two basic methods for preparing the statement of cash flows: the "direct" or the "indirect" method. Briefly, the indirect method starts with the excess of revenues over expenses and reconciles this number to operating cash flows. The direct method reports operating cash receipts and cash disbursements, directly adding these to arrive at operating cash flows. The authors believe the direct method is much more easily understood by readers of financial statements, and thus recommends its use.

Much of the information used to prepare a statement of cash flows is derived from data in the other two primary financial statements, some of it from the preceding year's statements. Thus, when planning to prepare this statement for the first time, it is helpful to start a year in advance so that the necessary prior-year data is available when needed.

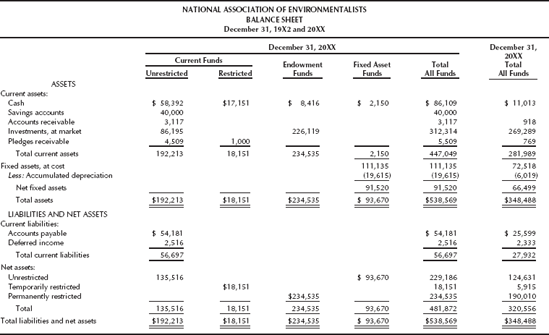

Sample financial statements, illustrating formats that contain the disclosures required by Statement No. 117, are shown in Appendix C to the Statement.

This document establishes one set of standards for all recipients of contributions, replacing the four different standards in the four AICPA audit guides. It also sets standards for donors of gifts; no explicit standards have heretofore existed, except for private foundations. For-profit organizations are also covered by this part of the document.

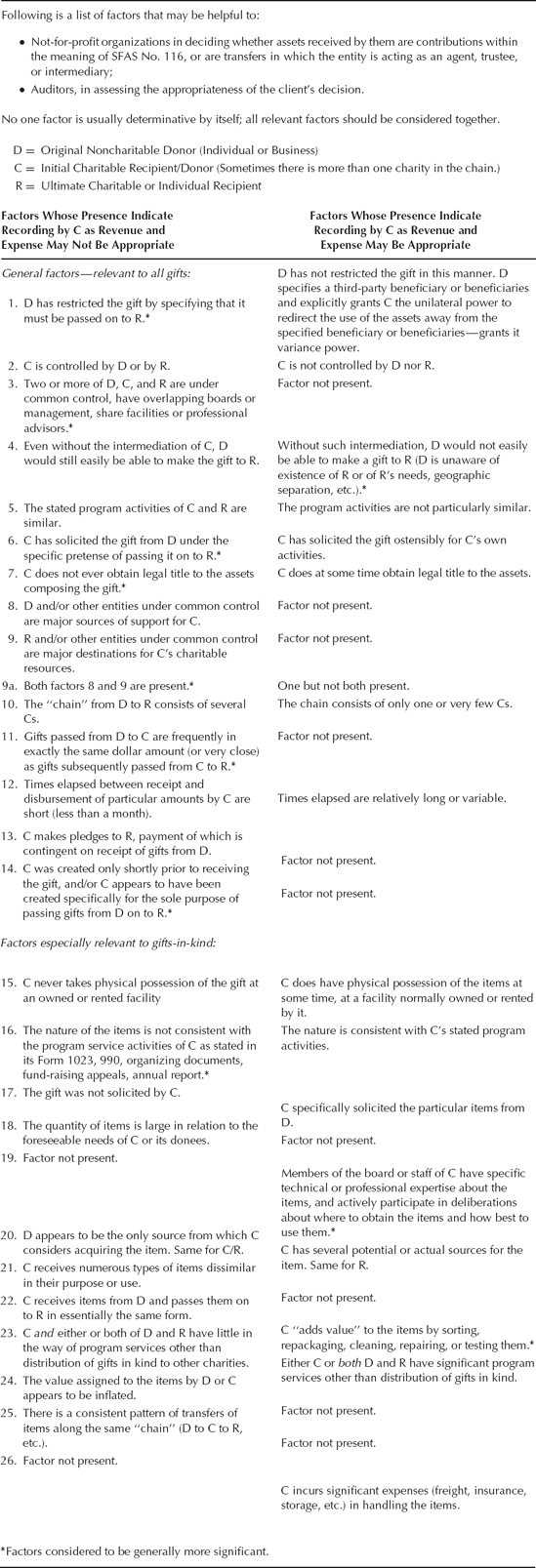

Certain types of transactions are not considered contributions: transactions that are in substance purchases of goods or services (even though they may be called grants) and transactions in which a recipient of a "gift" is merely acting as an agent or intermediary for, and passes the gift on to, another organization. Unfortunately, there is not much specific guidance for how to distinguish these two situations from real contributions; organizations will have to use judgment on a case-by-case basis.

SFAS No. 116 explicitly introduces a new concept into accounting for contributions: the conditional promise to give (pledge). This concept has implicitly existed for a long time, but has never before been articulated so clearly. A conditional pledge is one that depends on the occurrence of some specified uncertain future event to become binding on the pledgor. Examples of such events are the meeting of a matching requirement by the pledgee, or natural or man-made disasters such as a flood or fire. The mere passage of time is not a condition. Note that the concept of a condition is completely separate from that of a restriction. Conditions relate to events that must occur prior to a pledge becoming binding on the pledgor; restrictions relate to limits on the use of a gift after receipt.

Unconditional pledges are recorded at the time verifiable evidence of the pledge is received. Conditional pledges are not recorded until the condition is met, at which time they become unconditional. Pledges payable in future periods are considered implicitly time-restricted and are reported in the temporarily restricted class of net assets until they are due. Long-term pledges are also discounted to their present value to reflect the time value of money (in accordance with Accounting Principles Board Opinion No. 21); this is a new practice for most organizations. Accretion of the discount to par value will be reported as contribution income.

All contributions are reported as revenue, in the class of net assets (unrestricted, temporarily restricted, or permanently restricted) appropriate to any donor restrictions on the gift, at the time of receipt of the gift. This applies to unconditional pledges as well as cash gifts. The presence or absence of explicit or implicit donor-imposed time or purpose restrictions on the use of a gift do not affect the timing of revenue recognition, only the class in which they are reported. This principle is a significant change in practice for many organizations, which have heretofore deferred donor-restricted gifts and all pledges until a later period when the restriction was met or the pledge collected. The effect is to report higher net asset amounts, mainly in the temporarily restricted class, than under previous principles. This principle has generated a lot of controversy between those who favor retaining the previous deferral method and advocates of the new standard.

Accounting by donors for pledges and other contributions will follow the same principles with respect to recognition and timing as the donees, though of course all the accounting entries are reversed: expense instead of revenue, pledges payable instead of pledges receivable. Also, for-profit donors do not categorize their financial reports into classes because this concept only applies to not-for-profits.

The reporting of the value of donated services of volunteers has changed for many organizations under SFAS No. 116. The new standard requires reporting such a value if either of two criteria is met: (1) the services create or enhance nonfinancial assets, or (2) the services require specialized skills, are provided by persons possessing those skills, and would typically otherwise have to be purchased by the recipient if volunteers were not available. If neither criterion is met, the services may not be recorded. Organizations need to consider which of their volunteer services meet either of the two criteria.

Another matter that was controversial during the process of developing SFAS No. 116 was the question of accounting for museum collections. An early FASB proposal was to require capitalization of such assets. After much discussion of the subject, FASB agreed to allow noncapitalization of these items, if certain conditions relating to the items were met and certain footnote disclosures made.

Organizations have a number of decisions available to them under SFAS Nos. 116 and 117. These are:

Restricted contributions:

Do we wish to report restricted contributions whose restrictions are met in the same accounting period as that in which they are received as restricted or as unrestricted support? (Contributions paragraph 14, third sentence.)

Do we wish to adopt a policy which implies that on gifts of long-lived assets, there exists a time restriction which expires over the useful life of the donated assets? (Contributions paragraph 16.)

Basic financial statement format:

What titles do we wish to use for the balance sheet and for the statement of activity? (No particular titles are required or precluded by SFAS No. 117.)

Do we wish to present additional detail in the statement of financial position of assets and liabilities by class? (Display paragraph 156, next-to-last sentence.)

Which of the sample formats for the Statement of Activities do we wish to follow? (Display paragraph 157 and its examples that follow.)

Do we wish to present a measure of "operations"? (Display paragraphs 23, 163–167) (See Appendix 35.6 for further guidance.)

Do we wish to prepare the statement of cash flows using the direct or the indirect method? (SFAS No. 95, "Statement of Cash Flows," paragraphs 27–28.)

Do we wish to present comparative financial data for prior year(s)? (Display paragraph 70.)

Classification of expenses:

On the face of the statement of activities, do we wish to categorize expenses by functional or by natural classifications? (Display paragraph 26, second and third lines.)

If we are not required to disclose expenses in natural categories, do we wish to make such disclosure voluntarily? (Display paragraph 26, last sentence.)

If expenses have not previously been categorized by function, what categories (beyond the basic categories of program, management, fundraising, membership-development) do we wish to present? (Display paragraphs 26–28.)

Do we wish to disclose the fair value of contributed services received but not recognized as revenues? (Contributions paragraph 10, last sentence).

Collection items:

If our organization has assets that meet the definition of collection items at Contributions paragraph 11, do we wish to capitalize these assets or not?

If we have not previously capitalized but now wish to capitalize these items, do we wish to do so retroactively, or only prospectively? (Contributions paragraph 12.)

If we choose to capitalize these items retroactively, how do we wish to determine their value for this purpose? (Contributions, footnote 4.)

Do we wish to present nonmonetary information, as discussed in Display footnote 6?

Do we wish to retain our fund accounting system and convert our financial data to the new class structure by worksheets prior to preparing the financial statements, or do we wish to convert our entire accounting system to reflect the three-class structure discussed at Display paragraph 3 and Appendix D?

The division of net assets (formerly called fund balance) into three classes—unrestricted, temporarily restricted, and permanently restricted—as set forth in SFAC No. 6, and other matters discussed in that document, has a significant effect on the format of the financial statements of many not-for-profit organizations.

In 1996, the AICPA issued two new audit guides, one for health care organizations (discussed in Chapter 36 and one for all other not-for-profit organizations. It provides additional implementation guidance for FASB Statements Nos. 116, 117, and 124, as well as other matters affecting not-for-profit organizations. Topics it covers in particular detail include reporting of split-interest gifts and expenses. Its provisions are discussed throughout this chapter.

The AICPA issues technical practice aids to address questions it receives from practitioners. Preparers of not-for-profit organization financial statements should be familiar with these Technical Practice Aids (TPAs) that are included in the AICPA publication Technical Practice Aids at Section 6140.

Important aids that relate to the implementation of SFAS Nos. and 117 include the following:

6140.03 Lapsing of Time Restrictions on Receivables that Are Uncollected at Their Due Date. SFAS No. 116 requires that pledges receivable be recorded as temporarily restricted with an implied time restriction that expires on the due date. Practice is sometimes to release restrictions when a pledge is paid rather than when it comes due. This TPA clarifies that release should occur at the due date; the due date needs to be identified based on the specific circumstances.

6140.04 Lapsing of Restrictions on Receivables if Purpose Restrictions Pertaining to Long-Lived Assets Are Met before the Receivables Are Due. Many organizations raise funds for capital campaigns for building projects with pledges that are payable over a period that extends some time after the building is placed in to service. SFAS No. 116 provides that restrictions expire when the last restriction expires, but the contributions specified for the current period are not considered time restricted. Accordingly, it may be appropriate to release the restrictions on capital campaign pledges when the building is placed into service.

6140.05 NPO Accounting for Loans of Cash that Are Interest Free or that Have Below-Market Interest Rates. The TPA sets out the accounting to be followed to record the contribution of interest at fair value where an organization receives a loan that is interest free or below market. For loans with terms of more than one year, the value needs to be recorded for the full term of the loan at the time of the loan agreement, with recording of interest expense over the term of the loan.

6140.06 Functional Category of Costs of Sales of Contributed Inventory. The TPA recommends that organizations establish a separate classification for such cost of sales as a supporting activity unless the item sold relates to a program activity, in which case it would be reported as such.

6140.7 Functional Category of Costs of Special and 6140.08 Functional Category of the Costs of Direct Donor Benefits. The TPA clarifies that not all costs of special events, in particular the cost of direct benefits to donors, are fund-raising costs. However, direct benefits to donors are fund-raising costs if the donor has not paid specifically for those benefits in an exchange transaction such as purchasing a ticket to a special event.

6140.9 Reporting Bad Debt Losses. This TPA clarifies that bad debt losses cannot be netted against revenue. It should be noted, though, that losses do not have to be treated the same way as expenses in the statement of activities. Accordingly, to the extent that there is a bad debt loss related to a pledge that has not yet come due, that loss can be recorded as a reduction in temporarily or permanently restricted net assets. This can be helpful to an organization in not increasing the percentage of expenses that relate to supporting activities.

6140.10 Consolidation of Political Action Committee Political Action Committee PAC. This TPA clarifies that SOP 94-3 applies to the consolidation of political action committees (PACs). Accordingly, a PAC should be consolidated when its government committee is appointed by a not-for-profit organization that benefits from its activities.

6140.11 Costs of Soliciting Contributed Services and Time that Do Not Meet the Recognition Criteria in FASB Statement No. 116. This TPA arose from the practice of recording the costs of soliciting volunteers as a program activity. This is of particular importance to the many organizations that use volunteers extensively in meeting their program goals. In many cases the value of these services is not recognized in the financial statements consistent with the requirements of SFAS No. 116. The TPA clarifies that SFAS No. 117 requires that all costs of soliciting contributed services be recorded as fund raising even if the contributed services are not recognized in the financial statements. Organizations with large volunteer departments need to separately identify those costs of soliciting volunteers from the costs of managing volunteers, which may well be program in nature if the volunteers are meeting program goals. If such fund-raising costs are significant, organizations may wish to identify them separately in the financial statements so that readers can relate fund-raising costs with the value of the funds raised.

As of early 2002, the FASB was working on the following additional projects that are particularly applicable to not-for-profit organizations. For current status, refer to the FASB Web site at www.fasb.org.

The FASB issued Statement No. 141, "Business Combinations," and specifically excluded not-for-profit organizations. SFAS No. 142, "Goodwill and Intangible Assets," delays implementation for not-for-profit organizations until the FASB issues a statement on the combination of not-for-profit organizations.

The FASB tentatively determined that not-for-profit organizations should follow SFAS Nos. 141 and 142 except for circumstances in which a different approach is appropriate because of circumstances unique to not-for-profit organizations. Currently, not-for-profit organizations are required to account for business combinations and acquired intangible assets following the guidance in APB Opinion No. 16, "Business Combinations," and APB Opinion No. 17, "Tangible Assets." However, practice varies considerably and this results principally from combinations where there is no exchange of consideration. Many combinations of not-for-profit organizations have been accounted for using the pooling-of-interest method. The elimination of that method in SFAS No. 141 requires the development of clear guidance for not-for-profit organizations.

The FASB has tentatively concluded that a standard when issued will require identification of the acquiring organization in all combinations. The standard will include criteria to help identify the acquiring organization.

The assets and liabilities, including intangible assets, of the acquired organization will then need to be valued in accordance with the criteria applicable to business organizations in SFAS Nos. 141 and 142.

For combinations with no exchange of consideration, the acquiring organization will record the acquisition as receipt of a contribution in accordance with SFAS No. 116 at fair value.

In situations in which the fair value of the liabilities exceeds the fair value of the assets, the FASB has tentatively concluded that the difference should be accounted for as goodwill. However, the FASB is expected to reconsider this conclusion prior to the issuance of an exposure draft. Alternative approaches would appear to be to reduce the value of acquired assets so as not to exceed the value of the liabilities or to record the excess as an expense at the time of the combination.

For combinations in which there is an exchange of consideration, the FASB would require that SFAS No. 141 be followed. However, if the consideration is only part payment, the fair value of all assets and liabilities would need to be computed and the difference reported as a contribution.

A major difference for most combinations of not-for-profit organizations is the adjustment of values of assets and liabilities of the acquired organizations to fair value and the requirement to record the value of acquired intangible assets, including the value of trademarks and donor lists.

The FASB has not completed its deliberations, and an exposure draft is not expected until the first quarter of 2003.

The FASB has been considering a proposed Statement that would require business enterprises and not-for-profit organizations that control other entities to include those subsidiaries in their consolidated financial statements. "Control" would be defined as the nonshared decision-making ability of one entity to direct the policies and management that guide the ongoing activities of another entity so as to increase its benefits and limit its losses from that other entity's activities.

During 2001, the FASB determined that it had insufficient support to complete this project. FASB members had difficulty agreeing on the definition of "control." Accordingly, the FASB has suspended its work in this area. Not-for-profit organizations cannot expect new guidance in the near future, so the current rules on SOP 94-3 remain applicable (see Section 35.2(k), "Related Organizations.")

The various accounting standards discussed in this chapter affect considerably the accounting and financial reporting of all types of not-for-profit organizations. A list of the most significant requirements follows.

Accounting for Contributions (see SFAS No. 116, SFAS No. 136, and the AICPA Audit Guide)

Pledges are recorded when an unconditional promise to give is communicated to the donee.

A conditional promise to give is not reported until the condition is met.

(The distinction between conditional and restricted gifts is not always clear.)

Pledges are discounted to their present value and are reported net of an allowance for the estimated uncollectible amount.

All gifts, including pledges and restricted gifts, are reported as revenue when received.

Donors (including for-profit donors) must follow the same rules as donees (in reverse—an unconditional pledge must be recorded as an expense and a liability when made). (Fund-raisers should take note of this, as it will affect some donors' willingness to make unconditional pledges.)

Split-interest gifts are essentially treated as pledges (Audit Guide, Chapter 6); these include:

Gift annuities, remainder annuity trusts, unitrusts, Pooled Income Funds (PIF), lead trusts.

Irrevocable trusts held by others are reported in the beneficiary's financial statements.

Gifts-in-kind are recorded at fair value—including property, use of property, equipment, inventory for sale or use, services by other organizations (including bargain purchases).

Donated services of individual volunteers are recorded only when specified criteria are met:

The services create or enhance nonfinancial assets (building something), or

The services require specialized skills, the volunteer possesses those skills, and the donee would typically have to purchase the services if the volunteer were not available (the services involve a significant and central activity of the entity).

A pass-through entity may not be able to record gifts as revenue, depending on the circumstances of the gift.

A museum does not have to capitalize its collection if certain criteria are met.

New principles apply to transfers of cash or other financial assets from a donor to a recipient organization that agrees to use the assets on behalf of or transfer the assets to a specified beneficiary.

If the recipient organization and the specified beneficiary are unaffiliated, the recipient organization reports the assets at fair value and a liability of equal amount. However, if the donor explicitly grants the recipient organization variance power—unilateral power to redirect the use of the assets to another beneficiary—or if the recipient organization and the specified beneficiary are financially interrelated, the recipient organization reports the fair value of the assets as a contribution received.

A specified beneficiary reports its rights to the assets as an asset at fair value while it has rights to the assets, unless the donor explicitly granted the recipient organization variance power. If the beneficiary and the recipient organization are financially interrelated, the beneficiary reports at fair value its interest in the net assets of the recipient organization and adjusts that interest for its share of the change in net assets of the recipient organization. However, if the recipient organization is explicitly granted variance power, the specified beneficiary does not report its potential for receipts from the assets held by the recipient organization.

Financial statement format (see SFAS No. 117 and the AICPA Audit Guide)

Required disclosures are: totals of assets, liabilities, net assets, change in net assets.

Net assets (formerly, fund balance) and revenue are categorized into three classes:

Unrestricted; temporarily restricted; permanently restricted (per donor restrictions only).

Restrictions imposed by nondonors do not change category (e.g., contracts).

Required disclosures for each class are: net assets, change in net assets.

A statement of cash flows is required (the "direct" method is preferred).

All expenses are reported in the unrestricted class.

Temporarily restricted net assets are reclassified to match related expenses.

Expenses are reported on a functional basis (program, management, fund raising).

Revenues and expenses are reported gross, not net (exception: investment management fees).

Related items (e.g., sales/cost of sales) may be shown as: gross, deduction, net.

(See below for treatment of capital gains/losses.)

Affiliated entities are combined if specified criteria are met (SOP 94-3):

For-profit affiliate: criteria based on ownership.

Not-for-profit affiliate: criteria based on control and economic interest.

Accounting for Investments (see SFAS No. 117 and 124)

Marketable securities are reported at current market value.

Capital gains and losses on endowment are reported mostly in the unrestricted class, unless state law or a donor stipulation specifies otherwise.

Other Matters

Depreciable assets must be depreciated (see SFAS No. 93).

Not-for-profits must follow requirements of generally accepted accounting principles (see SOP 94-2).

Joint costs of multipurpose activities can be allocated to program functions only if certain criteria are met:

Purpose; audience; content, including a call to action other than giving (see SOP 98-2, which replaced SOP 87-2).

Contribution rules in SFAS No. 116 do not affect the timing of revenue recognition for advance payments of earned income: dues, fees, sales, season tickets, and so on—these are still deferred until earned.

Not-for-profit organizations frequently maintain their records on a cash basis, a bookkeeping process that reflects only transactions involving cash. On the other hand, most commercial organizations, as well as many medium and large not-for-profit organizations, keep accounts on an accrual basis. In accrual basis accounting, income is recognized when earned and expenses are recognized when incurred. For bookkeeping purposes, either basis is acceptable.

Each accounting basis has certain advantages. The principal advantage of cash basis accounting is simplicity—its procedures are easy to learn and easy to execute. Because of this simplicity, a cash basis accounting system is less complicated and less expensive to maintain than an accrual basis system. A less complicated system will be easier for a volunteer bookkeeper who does not feel comfortable with the more complicated accrual methods. Because there is often no material difference in financial results between cash and accrual basis accounting for small organizations, the incremental cost of an accrual basis system may be unwarranted. In addition, many not-for-profit organizations think it more prudent to keep their books on a cash basis. They often do not want to recognize income prior to the actual receipt of cash.

The principal advantage of accrual basis accounting is that it portrays financial position and results of operations on a more realistic basis—a complex organization with accounts receivable and bills outstanding can present realistic financial results only on the accrual basis. In addition, accrual basis accounting usually achieves a better matching of revenue and related expenses. Also, many individuals who use the financial statements of not-for-profit organizations, such as bankers, local businesspeople, and board members, are often more familiar with accrual basis accounting.

Organizations wanting the accuracy of accrual basis accounting, but not wishing to sacrifice the simplicity of cash basis bookkeeping, have alternatives. They may maintain their books on a cash basis and at year end record all payables, receivables, and accruals. These adjustments would permit presentation of accrual basis financial statements.

An organization can also keep its books on a cash basis, except for certain transactions that are recorded on an accrual basis. A popular type of "modified cash basis" accounting is to record accounts payable as liabilities are incurred, but to record income on a cash basis as received.

Fund accounting is the process of segregating resources into sets of self-balancing accounts on the basis of either restrictions imposed by donors or designations imposed by governing boards.

In the past, most not-for-profit organizations followed fund accounting procedures in accounting for resources. This was done because many organizations regard fund accounting as the most appropriate means of exercising stewardship over funds. Reporting all the details of funds, however, is not required of all not-for-profit organizations, and in many cases is not recommended. Fund accounting, if carried to its logical extreme, requires a separate set of accounts for each restricted gift or contribution; this leads to confusing financial statements that often present an organization as a collection of individual funds rather than as a single entity. Today, many not-for-profit organizations are combining funds and eliminating fund distinctions for reporting purposes to facilitate financial statement users' understanding of the organization as a whole.

The FASB Standard on financial reporting (SFAS No. 117) specifically requires the reporting of certain financial information by what it calls "classes" rather than funds.

An infinite variety of funds is possible. To limit the number of funds reported, broad fund classifications may be used. One scheme commonly used today is classification of resources by type of donor restriction. Another criterion for classifying funds is the degree of control an organization possesses over its resources. Under this approach, funds are combined for reporting purposes into two groupings—unrestricted and restricted. A third approach classifies resources on the basis of their availability for current expenditure on an organization's programs. Under this approach, funds are combined into two categories, expendable and nonexpendable.

When resources are classified by type of donor restriction, four fund groupings are commonly used—current unrestricted, current restricted, endowment, and fixed asset funds.

The current unrestricted fund contains assets over which the board has total managerial discretion. This fund includes unrestricted contributions, revenue, and other income and can be used in any manner at any time to further the goals of the organization. For all not-for-profit organizations, "board-designated" funds should be included with current unrestricted funds. Board-designated funds are voluntary segregations of unrestricted fund balances approved by the board for specific future projects or purposes.

Current restricted funds are resources given to an organization to be expended for specific operating purposes.

Endowment funds are amounts donated to an organization with the legal restriction that the principal be maintained inviolate either in perpetuity or for a stated period of time and amounts set aside by the organization's governing board for long-term investment. Investment income on such funds is generally unrestricted and should be reported in the current unrestricted fund. Occasionally, endowment gifts stipulate restricted uses for the investment income, and such restricted income should be reported in the appropriate fund.

The fixed asset fund represents the land, buildings, and equipment owned by an organization. Since these assets are usually unrestricted in the sense that the board can employ (or dispose of) them in any manner it wishes to further the goals of the organization, fixed assets need not be reported in a separate fund, and may be reported as part of the current unrestricted fund.

Under SFAS No. 117, organizations must access each component of each fund on an individual basis to determine into which class that fund balance (net assets) should be classified. This assessment, as to the temporarily and permanently restricted classes, is based only on the presence or absence of donor-imposed restrictions. All funds without donor-imposed restrictions must be classified as unrestricted, regardless of the existence of any board designations or appropriations.

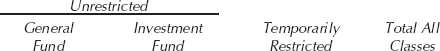

Following is a chart showing typical classes into which various types of fund balances will normally be classified:

Funds | Unrestricted | Temporarily Restricted | Permanently Restricted |

|---|---|---|---|

Endowment | Quasi | Term | Permanent |

Specific purpose, or current restricted | Board-designated | Donor-restricted | N/A |

Loan | Board-designated | Donor-restricted[a] | Revolving[a] |

Split-interest (annuity, life income, etc.) | Voluntary excess reserves | Unmatured | Permanent[b] |

Fixed asset | Expended;[c] Board-designated | Donor-restricted unexpended; Expended donated | See note [d] |

General/Operating | Unrestricted | Donor-time restricted | N/A |

Custodian | All (on balance sheet only)[e] | N/A | N/A |

[a] A permanently restricted loan fund would be one where only the income can be loaned, or, if the principal can be loaned, repayments of principal by borrowers are restricted to be used for future loans. A loan fund in which principal repayments are available for any use would be temporarily restricted until the loans are repaid, at which time such amounts would become unrestricted. [b] For example, an annuity fund that, upon maturity, becomes a permanent endowment. [c] Expended donor-restricted plant funds will be either unrestricted or temporarily restricted, depending on the organization's choice of accounting principle under paragraph 16 of SFAS No. 116. [d] Fixed assets could be permanently restricted if a donor has explicitly restricted the proceeds from any future disposition of the assets to reinvestment in fixed assets. Museum collection items received subject to a donor's stipulation that they be preserved and not sold might also be considered permanently restricted. [e] Note that because no transactions related to custodian funds are reported in the income statement of the holder of the assets, and because there is never a fund balance amount (assets are always exactly offset by liabilities), reporting of such funds as separate items becomes an issue only when a balance sheet is disaggregated into classes. The logic for reporting the assets and liabilities of custodian funds in the unrestricted class is that such assets are not the result of donor-restricted gifts, which is a requirement for recording items in one of the restricted classes. | |||

The use of fund accounting necessitates transfers in some situations to allocate resources between funds or classes. Financial statement readers often find it difficult to comprehend such reclassifications. In addition, if not properly presented, reclassifications may give the impression that an organization is willfully manipulating amounts reported as income.

To minimize confusion and the appearance of deception, transfers must not be shown as either income or expenses of the transferring fund. Reclassifications of the total organization are merely an internal reallocation of resources and in no way result in income or expense recognition.

Columnar statements, which present the activity of each class in separate, side-by-side columns, facilitate clear, comprehensive presentation of reclassifications.

Appropriations (or designations) are internal authorizations to expend resources in the future for specific purposes. They are neither expenditures nor legal obligations. When appropriation accounting is followed, appropriated amounts should be set aside in a separate account as part of the net assets of an organization.

Appropriation accounting is both confusing and subject to abuse. It is confusing because "appropriation" is an ambiguous term, and many readers do not understand that it is neither a current expenditure nor a binding obligation for a future expenditure. It is subject to abuse because, when treated incorrectly, appropriations can appear to reduce the current year's excess of revenue over expenses to whatever level the board wants. The board can then, at a later date, restore "appropriated" funds to the general use of the organization.

The use of appropriation accounting is not recommended. If an organization wishes to follow appropriation accounting techniques and wants to conform with GAAP, it must be certain that appropriations are not presented as expenses and that they appear only as part of the net assets of the organization. Expenses incurred out of appropriated funds should be charged as expenses in the year incurred, and the related appropriations should be reversed once an expense has been incurred.

Disclosure in notes is an alternative to appropriation accounting. Under this approach, an organization does not refer to appropriations in the body of its financial statements but instead discloses such amounts only in notes to the financial statements.

Treatment of fixed assets is sometimes a perplexing accounting issue confronting not-for-profit organizations. There are three reasons some not-for-profit organizations have historically not recorded a value for fixed assets on their balance sheets. First, many not-for-profit organizations have not been as interested in matching income and expenses as are businesses. This being the case, management of these organizations has felt no compelling need to record assets and then charge depreciation expense against current income. Second, the principal asset of some not-for-profit organizations is real estate that was often acquired many years previously. In these inflationary times, many organizations do not wish to carry at cost and depreciate assets now worth several times their original purchase price. Third, many not-for-profit organizations plead poverty as a means of raising funds. By not recording fixed assets, they appear less substantial than they in fact are.

Confusion concerning fixed assets has been heightened by lack of a universally accepted treatment for fixed assets. Historically, there have been three common alternatives for handling fixed assets: immediate write-off, capitalization (with or without depreciation), and write-off, followed by capitalization.

Immediate write-off is the simplest method of treating fixed assets and is used most frequently for small organizations and those on a cash basis. Under this method, an organization expenses fixed asset purchases immediately on the statement of income and expenses.

The principal advantage of this approach is simplicity—the bookkeeping complexities of capitalization are avoided, and the amount of excess revenue over expenses reported on the statement of income and expenses more closely reflects the amount of money at the board's disposal.

The major disadvantage of immediate write-off is that the historical costs of an organization's fixed assets are not recorded, and its balance sheet does not present the true net worth of the organization. Another disadvantage is that expensing fixed assets may produce fluctuations in net income that are largely unrelated to operations. Finally, this approach does not conform with GAAP.

A second alternative available to an organization is to capitalize all major fixed asset purchases. Under this approach, all major fixed assets are reflected on the organization's balance sheet.

The principal advantage of this approach is that it conforms with GAAP and permits an auditor to express an unqualified opinion on an organization's financial statements. It also documents the amount of assets the organization controls, permitting evaluation of management performance, and allows the organization to follow depreciation accounting.

The major disadvantage of capitalization is that it renders financial statements more complex. An unsophisticated statement reader may conclude that an organization has more funds available for current spending than it actually has.

A third alternative is to immediately write off fixed asset purchases on the statement of income and expenses and then capitalize these assets on the balance sheet. This method permits an organization to report expenditures for fixed asset purchases on the statement of income and expenses, thus offsetting any excess of income over expenses that may have been caused by contributions received for fixed assets on its balance sheet.

However, this approach is very confusing, is inconsistent with other accounting conventions, does not permit depreciation accounting in a traditional sense, and does not constitute GAAP. Accordingly, the use of this approach is strongly discouraged.

Some organizations purchase or receive fixed assets under research or similar grants which provide that, at the completion of the grant period, the right of possession of these fixed assets technically reverts to the grantor. If the grantor is not expected to ask for their return, a fixed asset, whether purchased or donated, should be recorded as an asset and depreciated as with any other asset.

Depreciation has been as thorny a problem for not-for-profit organizations as the problem of fixed assets. If an organization capitalizes fixed assets, it is immediately confronted with the question of whether it should depreciate them: that is, allocate the cost over the estimated useful life of the assets.

Depreciation accounting is now a generally accepted practice for most not-for-profit organizations, and since 1990, it constitutes GAAP for all not-for-profit organizations. (Prior to that year it was optional for colleges.) SFAS No. 93, "Recognition of Depreciation by Not-for-Profit Organizations," requires not-for-profit organizations to record depreciation on fixed assets. Many arguments in favor of recording depreciation, such as the following, are valid for not-for-profit organizations:

Depreciation is a cost of operations. Organizations cannot accurately measure the cost of providing a product or service or determine a fair price without including this cost component.

Most organizations replace at least some fixed assets out of recurring income. If depreciation is not recorded, an organization may think that its income is sufficient to cover costs when, in reality, it is not.

If depreciation is not recorded, income may fluctuate widely from year to year, depending on the timing of asset replacement and the replacement cost of assets.

Organizations that are "reimbursed" by a government agency for the sale of goods or services must depreciate fixed assets if they wish to recapture all costs incurred.

Some not-for-profit organizations pay federal income tax on "unrelated business income." Depreciation should be reported as an expense to reduce income subject to tax.

Depreciation is computed in the same manner as that used by commercial enterprises. Depreciation is reported as an item of expense on the statement of income and expenses, and accumulated depreciation is reported under the "fixed assets" caption on the balance sheet.

If fixed asset purchases are capitalized but not written down through regular depreciation charges in the statement of income and expenses, it may be necessary to periodically write down their carrying value so that the balance sheet is not overstated. The preferred method of achieving this is to report the write-down as an expense on the statement of income and expenses and to reduce the asset value on the balance sheet.

Dividends and interest earned on unrestricted investment funds, including board-designated funds, should be reported as income in the unrestricted class.

Unrestricted investment income earned on endowment funds should also be reported as income directly in the unrestricted class.

Restricted investment income should be reported directly in the appropriate restricted fund. For example, if the donor of an endowment fund gift specifies that the investment income be used for a particular purpose, investment income should be reported directly in the temporarily restricted class rather than the unrestricted or the permanently restricted class.

The FASB reporting standard in Statement No. 117 required many organizations to change their method of reporting gains and losses on endowment funds from the method previously used and described in the seventh edition of this book. Briefly, the new method involves determining which portion of the gains are legally restricted, either by explicit donor restrictions or by applicable laws to which the organization is subject. All gains not so restricted will be reported directly in the unrestricted class rather than in the endowment fund.

Realized gains or losses on unrestricted investment funds should be reported directly in the unrestricted class. Unrestricted capital gains or losses may be reported in the statement of income and expenses as an income item along with dividends and interest, or they may be reported separately from other investment income, above the caption "Change in net assets."

Realized gains or losses on endowment investments were traditionally treated as adjustments to principal of the endowment fund. They have not been considered as income and were thought to possess the same restrictions as those that are attached to the principal. The legal status of gains or losses on endowment funds—as unrestricted income or as a component of restricted principal—is, however, currently discussed in SFAS No. 117. Where permitted by state law, such gains or losses should be treated as income and reported with dividends and interest in the unrestricted class above the caption "change in net assets." Restricted gains or losses may be treated in a similar manner except that they are reported in the appropriate restricted class.

Unrealized gains or losses did not pose accounting questions for not-for-profit organizations prior to 1973 because, before that year, investments could be carried only at cost and gains or losses were realized only at the time investments were sold or otherwise disposed of.

After 1973, the tenor of accounting pronouncements on the carrying value of investments and the treatment of unrealized gains or losses changed dramatically. In 1973 and 1974, the AICPA Industry Audit Guides for colleges and universities and voluntary health and welfare organizations permitted those organizations to carry their investments at either cost or market. Hospitals were required in 1978 to carry equity investments at market if the fair value dipped below cost. SOP 78-10 permitted covered organizations to carry investments at market or the lower of cost or market.

When investments are carried at market, gains and losses are recognized on a continuing basis. Realized and unrealized gains or losses should be reported together in a single caption: "net increase (decrease) in carrying value of investments." It is appropriate to report this increase or decrease in the same section in which investment dividends and interest are reported.

In 1995, SFAS No. 124 was issued. Its requirements include:

Equity securities that have readily determinable fair market values and all debt securities shall be reported at current fair value.

In the absence of donor stipulations or law to the contrary:

— Capital losses shall reduce temporarily restricted net assets to the extent that donor-imposed restrictions on net appreciation of the fund have not yet been met.

— Any remaining loss shall reduce unrestricted net assets.

— Gains that restore previous losses shall be reported in the unrestricted class.

Even when investments are carried at cost, if market value declines "permanently" below cost, the carrying value of this investment should be written down to the market value. This is accomplished by setting up a "provision for decline in market value of investments" in the statement of income and expenses in the same section where realized gains or losses are presented.

Support for a not-for-profit organization can be received in many different forms. Each of the types of contributions will be discussed in a separate section of this chapter.

In 1993, the controversy about proper accounting for contributions was settled by the issuance of SFAS No. 116, "Accounting for Contributions Received and Contributions Made." In brief, it says that all contributions, whether unrestricted or restricted, and in whatever form—cash, gifts-in-kind, securities, pledges, or other forms—are revenue in full immediately upon receipt of the gift or an unconditional pledge. (The practice in many organizations was for restricted contributions not to be deferred until the restriction was met.) The revenue is reported in the class of net assets appropriate to any donor-imposed restriction on the gift (unrestricted, if there is no donor-imposed restriction). It also contains guidance on accounting for donated services of volunteers and an exception to the normal rule when dealing with museum collection objects.

This section discusses simple unrestricted cash gifts. Unrestricted gifts in other forms, such as pledges, gifts of securities, and gifts of equipment and supplies, are discussed in later sections. The general principles discussed here apply to all unrestricted gifts, in whatever form received.

Historical Practices. All unrestricted contributions should be recorded in the current unrestricted fund. This principle is fairly well accepted and followed by most not-for-profit organizations. What was not uniformly followed is a single method of reporting such unrestricted contributions. Some organizations followed the practice of adding unrestricted contributions directly to the fund balance either in a separate Statement of Changes in Fund Balances or in the fund balance section where a combined Statement of Income, Expenses, and Changes in Fund Balances was used. Others reported some or all of their contributions directly in an unrestricted investment fund, and worse still, some reported unrestricted contributions directly in the endowment fund as though such amounts were restricted. The result of all these practices was to make it difficult for the readers of the financial statements to recognize the amount and nature of contributions received. Sometimes this was done deliberately in an attempt to convince the readers that the organization badly needed more contributions.

Accounting for Unrestricted Contributions. All unrestricted contributions should be reported in the unrestricted class of net assets in a Statement of Income and Expenses or, if a combined Statement of Income, Expenses, and Changes in Net Assets is used, such unrestricted contributions should be shown before arriving at the "Excess of income over expenses" caption. It is not acceptable to report unrestricted contributions in a separate Statement of Changes in Net Assets or to report such gifts in a restricted class of net assets.

Bargain Purchases. Organizations are sometimes permitted to purchase goods or services at a reduced price that is granted by the seller in recognition of the organization's charitable or educational status. In such cases, the seller has effectively made a gift to the buyer. This gift should be recorded as such if the amount is significant. For example, if a charity buys a widget for $50 that normally sells for $80, the purchase should be recorded at $80, with the $30 difference being reported as a contribution.

It is important to record only true gifts in this way. If a lower price is really a normal discount available to any buyer who requests it, then there is no contribution. Such discounts include quantity discounts, normal trade discounts, promotional discounts, special offers, or lower rates (say, for professional services) to reflect the seller's desire to utilize underused staff or sale prices to move slow-moving items off the shelves.

Current restricted contributions are contributions that can be used to meet the current expenses of the organization, although restricted to use for some specific purpose or during or after some specified time. An example of the former would be a gift "for cancer research" (a "purpose restriction") and, of the latter, a gift "for your 20XX activities" (a "time restriction"). In practice, the distinction between restricted gifts and unrestricted gifts is not always clear. In many cases, the language used by the donor leaves doubt as to whether there really is a restriction on the gift.

Current restricted contributions cause reporting problems, in part because the accounting profession took a long time to resolve the appropriate accounting and reporting treatment for these types of gifts. The resolution arrived at is controversial because many believe it is not the most desirable method of accounting for such gifts.

The principal accounting problem relates to the question of what constitutes "income" or "support" to the organization. Is a gift that can only be used for a specific project or after a specified time "income" to the organization at the time the gift is received, or does this restricted gift represent an amount which should be looked on as being held in a form of escrow until it is expended for the restricted purpose (cancer research in the above example), or the specified time has arrived (20XX in the above example)? If it is looked on as something other than income, what is it—deferred income or part of a restricted net asset balance?

If a current restricted gift is considered income or support in the period received—whether expended or not—the accounting is fairly straightforward. It would be essentially the same as for unrestricted gifts, described earlier, except that the gift is reported in the temporarily restricted class rather than in the unrestricted class of net assets. But if the other view is taken, the accounting can become complex.

The approach required by SFAS No. 116 is to report a current restricted gift as income or support in full in the year received, in the temporarily restricted class of net assets. In this approach, gifts are recognized as income as received and expenditures are recognized as incurred. The unexpended income is reflected as part of temporarily restricted net assets.

Observe, however, that in this approach, a current restricted gift received on the last day of the reporting period will also be reflected as income, and this would increase the excess of support over expenses reported for the entire period. Many boards are reluctant to report such an excess in the belief this may discourage contributions or suggest that the board has not used all of its available resources. Those who are concerned about reporting an excess of income over expenses are therefore particularly concerned with the implications of this approach: a large unexpected current restricted gift may be received at the last minute, resulting in a large excess of income over expenses.

Others, in rejecting this argument, point out that the organization is merely reporting what has happened and to report the gift otherwise is to obscure its receipt. They point out that in reality all gifts, whether restricted or unrestricted, are really at least somewhat restricted and only the degree of restriction varies; even "unrestricted" gifts must be spent realizing the stated goals of the organization, and therefore such gifts are effectively restricted to this purpose even though a particular use has not been specified by the contributor.

There are valid arguments on both sides. This approach is the one recommended in the AICPA Audit Guide for Voluntary Health and Welfare Organizations and therefore has been very widely followed. It will now become the method used by all not-for-profit organizations if they want their independent auditor to be able to say that their financial statements are prepared in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles.

Grants for Specific Projects. Many organizations receive grants from third parties to accomplish specific projects or activities. These grants differ from other current restricted gifts principally in the degree of accountability the recipient organization has in reporting back to the granting organization on the use of such monies. In some instances, the organization receives a grant to conduct a specific research project, the results of which are turned over to the grantor. The arrangement is similar to a private contractor's performance on a commercial for-profit basis. In that case, the "grant" is essentially a purchase of services. It would be accounted for in accordance with normal commercial accounting principles, which call for the revenue to be recognized as the work under the contract is performed. In other instances, the organization receives a grant for a specific project, and while the grantee must specifically account for the expenditure of the grant in detail and may have to return any unexpended amounts, the grant is to further the programs of the grantee rather than for the benefit of the grantor. This kind of grant is really a gift, not a purchase.

The line between ordinary current restricted gifts and true "grants" for specific projects is not important for accounting purposes because the method of reporting revenue is now the same for both. What can get fuzzy is the distinction between grants and purchase of services contracts. Most donors of current restricted gifts are explicit as to how their gifts are to be used, and often the organization will initiate a report back to the donors on the use of their gifts. However, restricted gifts and grants usually do not have the degree of specificity that is attached to purchase contracts. Appendix 35.1 contains a checklist to help readers distinguish between gifts and purchase contracts in practice.

Grants and contracts can be structured in either of two forms: In one, the payor remits the amount up front and the payee then spends that money. In the other, the payee must spend its own money from other sources and is reimbursed by the payor.

In the case of a purchase contract, amounts remitted to the organization in advance of their expenditure should be treated as deferred income until such time as expenditures are made that can be charged against the contract. At that time, income should be recognized to the extent earned. Where expenditures have been made but the grantor has not yet made payment, a receivable should be set up to reflect the grantor's obligation.

In the case of a true grant (gift), advance payments must be recognized as revenue immediately upon receipt, as is the case with all contributions under SFAS No. 116. Reimbursement grants are recognized as revenue as reimbursements become due, that is, as money is spent that the grantor will reimburse. This is the same method as is used under cost-reimbursement purchase contracts.

Some organizations have recorded the entire amount of the grant as a receivable at the time awarded, offset by deferred grant income on the liability side of the balance sheet. This is no longer appropriate under SFAS No. 116. If the entire grant amount qualifies as an unconditional pledge (see below), then that amount must be recorded as revenue, not deferred revenue.

Frequently, an organization will receive contributions that are in the form of investment securities: stocks and bonds. These contributions should be recorded in the same manner as cash gifts. The only problem usually encountered is difficulty in determining a reasonable basis for valuation in the case of closely held stock with no objective market value.

The value recorded should be the fair market value at the date received. Marketable stocks and bonds present no serious valuation problem. They should be recorded at their market value on the date of receipt or, if sold shortly thereafter, at the amount of proceeds actually received. However, the "shortly thereafter" refers to a sale within a few days or perhaps a week after receipt. Where the organization deliberately holds the securities for a period of time before sale, the securities should be recorded at their fair market value on the date of receipt. This will result in a gain or loss being recorded when the securities are subsequently sold (unless the market price remains unchanged).

For securities without a published market value, the services of an appraiser may be required to determine the fair value of the gift. See Subsection 35.2(b) for further discussion of investments.

Contributions of fixed assets can be accounted for in one of two ways. SFAS No. 116 permits such gifts to be reported as either unrestricted or temporarily restricted income at the time received. If the gift is initially reported as temporarily restricted, the restriction is deemed to expire ratably over the useful life of the asset: that is, in proportion to depreciation for depreciable assets. The expiration is reported as a reclassification from the temporarily restricted to the unrestricted class of net assets. Nondepreciable assets such as land would remain in the temporarily restricted class indefinitely—until disposed of. (Recognizing the gift as income in proportion to depreciation recognized on the asset is not in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles.)

Supplies and equipment should be recorded at the amount that the organization would normally have to pay for similar items. A value for used office equipment and the like can usually be obtained from a dealer in such items. The valuation of donated real estate is more difficult, and it is usually necessary to get an outside appraisal to determine the value.

Despite some controversy over the subject, the new AICPA Audit Guide specifically requires the recording of a value for contributed inventory expected to be sold by thrift shops and similar organizations at the time the items are received. The amount will be an estimate based on the estimated quantities and quality of goods on hand and known statistics for the percentage of the goods that will eventually be sold for cash (versus given away or discarded).

SFAS No. 116 makes an exception for recording a value for donated (and purchased) museum collection objects, if certain criteria are met and certain disclosures are made. Owners of such objects do not have to record them, although they may if they wish.

Many organizations depend almost entirely on volunteers to carry out their programs and sometimes supporting functions. Should such organizations place a value on these contributed services and record them as "contributions" in their financial statements?

Criteria for Recording. The answer is yes, under certain circumstances. These circumstances exist only when either of the following two conditions is satisfied:

The services create or enhance nonfinancial assets; or

The services:

Require specialized skills,

Are provided by persons possessing those skills, and

Would typically have to be purchased if not provided by donation.

If neither criterion is met, SFAS No. 116 precludes recording a value for the services, although disclosure in a footnote is encouraged. These criteria differ considerably from criteria in the earlier Audit Guides/SOP.

Creating or Enhancing Fixed Assets. The first criterion is fairly straightforward. It covers volunteers constructing or making major improvements to buildings or equipment. It would also cover things like building sets or making costumes for a theater or opera company, and writing computer programs, since the resulting assets could be capitalized on the balance sheet. The criterion says "nonfinancial" assets so as not to cover volunteer fund-raisers who, it could be argued, are "creating" assets by soliciting gifts.

Specialized Skills. The second criterion has three parts, all of which must be met for recording to be appropriate. The first part deals with the nature of the services themselves. The intent is deliberately to limit the types of services that must be recorded, thus reducing the burden of tracking and valuing large numbers of volunteers doing purely routine work, the aggregate financial value of which would usually be fairly small. SFAS No. 116 gives very little guidance about how to identify, in practice, those skills that would be considered "specialized," as opposed to nonspecialized. There is a list of skills that are considered specialized, but it merely recites a list of obvious professions, such as doctors, lawyers, teachers, carpenters. What is lacking is an operational definition of specialized that can be applied to all types of services. Appendix 35.2 contains a checklist to help readers make this distinction in practice.

The second part of the criterion will usually cause no problems in practice, as persons practicing the types of skills contemplated should normally possess the skills (if not, why are they performing the services?).

Would Otherwise Purchase. The third part of the criterion will be the most difficult of all to consider, as it calls for a pure judgment by management. Would the organization or would it not purchase the services? This is similar to one in SOP 78-10, which was as follows:

The services performed are significant and form an integral part of the efforts of the organization as it is presently constituted; the services would be performed by salaried personnel if donated services were not available ...; and the organization would continue the activity.

Probably the most important requirement is that the services being performed are an essential part of the organization's program. The key test is whether the organization would hire someone to perform these services if volunteers were not available.

This is a difficult criterion to meet. Many organizations have volunteers involved in peripheral areas which, while important to the organization, are not of such significance that paid staff would be hired in the absence of volunteers. But this is the acid test: If the volunteers suddenly quit, would the organization hire replacements? Appendix 35.3 contains a checklist to help readers assess this criterion.

Basis on Which to Value Services. An additional criterion that is not explicitly stated in SFAS No. 116 in connection with donated services is that there must be an objective basis on which to value these services. It is usually not difficult to determine a reasonable value for volunteer services where the volunteers are performing professional or clerical services. By definition, the services to be recorded are only those for which the organization would in fact hire paid staff if volunteers were not available. This suggests that the organization should be able to establish a reasonable estimate of what costs would be involved if employees had to be hired.

In establishing such rates, it is not necessary to establish individual rates for each volunteer. Instead, the volunteers can be grouped into general categories and a rate established for each category.

Some organizations are successful in getting local businesses to donate one of their executives on a full- or part-time basis for an extended period of time. In many instances, the amount paid by the local business to the loaned executive is far greater than the organization would have to pay for hired staff performing the same function. The rate to be used in establishing a value should be the lower rate. This also helps to get around the awkwardness of trying to discern actual compensation.

An organization may wish not to record a value unless the services are significant in amount. There is a cost to keep the records necessary to meet the reporting requirements, and unless the resulting amounts are significant, it is wasteful for the organization to record them.

Accounting Treatment. The dollar value assigned to contributed services should be reflected as income in the section of the financial statements where other unrestricted contributions are shown. In most instances, it is appropriate to disclose the amount of such services as a separate line.