Clifford H. Schwartz, CPA

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP

Suzanne McElyea, CPA

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP

Real estate encompasses a variety of interests (developers, investors, lenders, tenants, homeowners, corporations, conduits, etc.) with a divergence of objectives (tax benefits, security, long-term appreciation, etc.). The industry is also a tool of the federal government's income tax policies (evidenced by the rules on mortgage interest deductions and restrictions on "passive" investment deductions). The real estate industry consists primarily of private developers and builders.

Other important forces in the industry include pension funds and insurance companies and large corporations, whose occupancy (real estate) costs generally are the second largest costs after personnel costs.

After a decade of growth spurred by steadily falling interest rates in an expanding economy, the new millennium brought in its wake a series of traumatic events that highlighted the uncertainties inherent in the real estate industry:

Collapse of the dot-coms. The sudden rise and dramatic collapse of the Internet-related economy delivered the first shock to real estate markets since the banks scandals of the 1980s. A seller's market was turned on end as rapid retrenchment left behind a glut of office space.

The attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. The attacks dealt a hard blow to an already declining economy and real estate market. It exposed the vulnerability of the United States to terrorist attacks and made planning for such attacks a central part of real estate management. It was followed by a sharp rise in unemployment and severe weakness in financial markets. It also called into question long time practices of concentrating corporate functions and resources in one location.

Enron. The collapse of Enron led investors and regulators to seriously question the use of off-balance sheet financing vehicles, such as conduits and synthetic leasing, which had become the darlings of Wall Street financiers, growing to more than $5.2 trillion over the last 30 years.

Overbuilding, accounting reform, terrorist threats, and weak markets will continue to plague the recovery of many real estate markets. The sources and extent of available capital for financings and construction will be a concern. This concern will be centered on the ability and willingness of financing institutions to continue lending in an uncertain market, and lenders will increasingly require creditworthiness or enhancements to reduce to their exposure to real estate risk.

Real estate sales transactions are generally material to the entity's financial statements. "Is the earnings process complete?" is the primary question that must be answered regarding such sales. In other words, assuming a legal sale, have the risks and rewards of ownership been transferred to the buyer?

Prior to 1982, guidance related to real estate sales transactions was contained in two American Institute of Certified Public AccountantsAmerican Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Accounting Guides: "Accounting for Retail Land Sales" and "Accounting for Profit Recognition on Sales of Real Estate." These guides had been supplemented by several AICPA Statements of Position that provided interpretations

In October 1982, Statement of Financial Accounting StandardsStatement of Financial Accounting Standards (SFAS) No. 66, "Accounting for Sales of Real Estate," was issued as part of the Financial Accounting Standards BoardFinancial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) project to incorporate, where appropriate, AICPA Accounting Guides into FASB Statements. This Statement adopted the specialized profit recognition principles of the above guides.

The FASB formed the Emerging Issues Task ForceEmerging Issues Task Force (EITF) in 1984 for the early identification of emerging issues. The EITF has dealt with many issues affecting the real estate industry, including issues that clarify or address SFAS No. 66.

Regardless of the seller's business, SFAS No. 66 covers all sales of real estate, determines the timing of the sale and resultant profit recognition, and deals with seller accounting only. This Statement does not discuss nonmonetary exchanges, cost accounting, and most lease transactions or disclosures.

The two primary concerns under SFAS No. 66 are:

Has a sale occurred?

Under what method and when should profit be recognized?

The concerns are answered by determining the buyer's initial and continuing investment and the nature and extent of the seller's continuing involvement. The guidelines used in determining these criteria are complex and, within certain provisions, arbitrary. Companies dealing with these types of transactions are often faced with the difficult task of analyzing the exact nature of a transaction in order to determine the appropriate accounting approach. Only with a thorough understanding of the details of a transaction can the accountant perform the analysis required to decide on the appropriate accounting method.

SFAS No. 66 (pars. 44– 50) discussed separate rules for retail land sales (see Subsection 30.2(h)). The following information is for all real estate sales other than retail land sales. To determine whether profit recognition is appropriate, a test must first be made to determine whether a sale may be recorded. Then additional tests are made related to the buyer's investment and the seller's continued involvement.

Generally, real estate sales should not be recorded prior to closing. Since an exchange is generally required to recognize profit, a sale must be consummated. A sale is consummated when all the following conditions have been met:

The parties are bound by the terms of a contract.

All consideration has been exchanged.

Any permanent financing for which the seller is responsible has been arranged.

All conditions precedent to closing have been performed.

Usually all those conditions are met at the time of closing. On the other hand, they are not usually met at the time of a contract to sell or a preclosing.

Exceptions to the "conditions precedent to closing" have been specifically provided for in SFAS No. 66. They are applicable where a sale of property includes a requirement for the seller to perform future construction or development. Under certain conditions, partial sale recognition is permitted during the construction process because the construction period is extended. This exception usually is not applicable to single-family detached housing because of the shorter construction period.

Transactions that should not be treated as sales for accounting purposes because of continuing seller's involvement include the following:

The seller has an option or obligation to repurchase the property.

The seller guarantees return of the buyer's investment.

The seller retains an interest as a general partner in a limited partnership and has a significant receivable.

The seller is required to initiate or support operations or continue to operate the property at its own risk for a specified period or until a specified level of operations has been obtained.

If the criteria for recording a sale are not met, the deposit, financing, lease, or profit sharing (co-venture) methods should be used, depending on the substance of the transaction.

Once it has been determined that a sale can be recorded, the next test relates to the buyer's investment. For the seller to record full profit recognition, the buyer's down payment must be adequate in size and in composition.

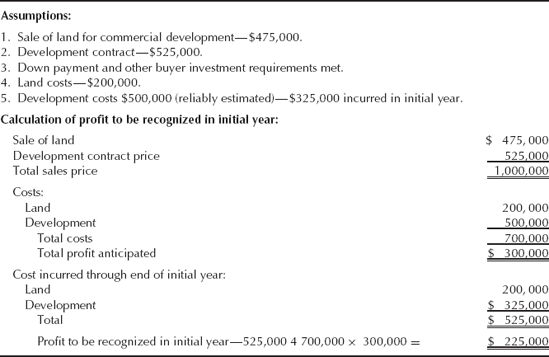

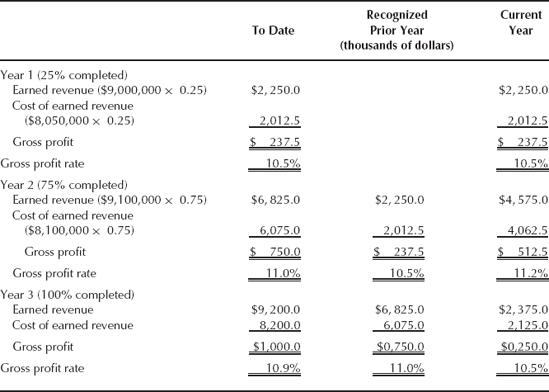

The minimum down payment requirement is one of the most important provisions in SFAS No. 66. Appendix A of this pronouncement, reproduced here as Exhibit 30.1, lists minimum down payments ranging from 5 percent to 25 percent of sales value based on usual loan limits for various types of properties. These percentages should be considered as specific requirements because it was not intended that exceptions be made. Additionally, EITF Consensus No. 88-24, "Effect of Various Forms of Financing under FASB Statement No. 66," discusses the impact of the source and nature of the buyer's down payment on profit recognition. Exhibit A to EITF No. 88-24 has been reproduced here as Exhibit 30.2

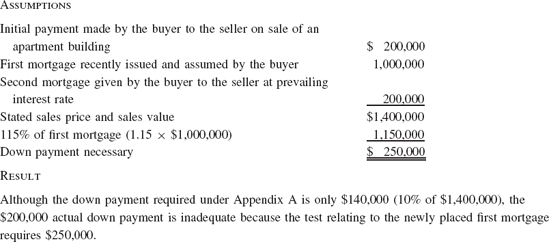

If a newly placed permanent loan or firm permanent loan commitment for maximum financing exists, the minimum down payment must be the higher of (1) the amount derived from Appendix A or (2) the excess of sales value over 115 percent of the new financing. However, regardless of this test, a down payment of 25 percent of the sales value of the property is usually considered sufficient to justify the recognition of profit at the time of sale.

Figure 30.1. Minimum initial investment requirements. (Source: SFAS No. 66, "Accounting for Sales of Real Estate" (Appendix A), FASB, 1982. Reprinted with permission of FASB.)

Figure 30.2. Examples of the application of the EITF consensus on Issue No. 88-24. Source: EITF Issue No. 88-24, "Effect of Various Forms of Financing under FASB Statement No. 66" (Exhibit 88-24A), FASB, 1988. (Reprinted with permission of FASB.)

An example of the down payment test—Appendix A compared to the newly placed permanent loan test—is given in the following:

The down payment requirements must be related to sales value, as described in SFAS No. 66 (par. 7). Sales value is the stated sales price increased or decreased for other consideration that clearly constitutes additional proceeds on the sale, services without compensation, imputed interest, and so forth.

Consideration payable for development work or improvements that are the responsibility of the seller should be included in the computation of sales value.

The primary acceptable down payment is cash, but additional acceptable forms of down payment are:

Notes from the buyer (only when supported by irrevocable letters of credit from an independent established lending institution)

Cash payments by the buyer to reduce previously existing indebtedness

Cash payments that are in substance additional sales proceeds, such as prepaid interest that by the terms of the contract is applied to amounts due the seller

Examples of other forms of down payment that are not acceptable are:

Other noncash consideration received by the seller, such as notes from the buyer without letters of credit or marketable securities. Noncash consideration constitutes down payment only at the time it is converted into cash.

Funds that have been or will be loaned to the buyer builder/developer for acquisition, construction, or development purposes or otherwise provided directly or indirectly by the seller. Such amounts must first be deducted from the down payment in determining whether the down payment test has been met. An exemption from this requirement was provided in paragraph 115 of SFAS No. 66, which states that if a future loan on normal terms from a seller who is also an established lending institution bears a fair market interest rate and the proceeds of the loan are conditional on use for specific development of or construction on the property, the loan need not be subtracted in determining the buyer's investment.

Funds received from the buyer from proceeds of priority loans on the property. Such funds have not come from the buyer and therefore do not provide assurance of collectibility of the remaining receivable; such amounts should be excluded in determining the adequacy of the down payment. In addition, EITF Consensus No. 88-24 provides guidelines on the impact that the source and nature of the buyer's initial investment can have on profit recognition.

Marketable securities or other assets received as down payment will constitute down payment only at the time they are converted to cash.

Cash payments for prepaid interest that are not in substance additional sales proceeds.

Cash payments by the buyer to others for development or construction of improvements to the property.

If the buyer's down payment is inadequate, the accrual method of accounting is not appropriate, and the deposit, installment, or cost recovery method of accounting should be used.

When the sole consideration (in addition to cash) received by the seller is the buyer's assumption of existing nonrecourse indebtedness, a sale could be recorded and profit recognized if all other conditions for recognizing a sale were met. If, however, the buyer assumes recourse debt and the seller remains liable on the debt, he has a risk of loss comparable to the risk involved in holding a receivable from the buyer, and the accrual method would not be appropriate.

EITF Consensus No. 88-24 states that the initial and continuing investment requirements for the full accrual method of profit recognition of SFAS No. 66 are applicable unless the seller receives one of the following as the full sales value of the property:

Cash, without any seller contingent liability on any debt on the property incurred or assumed by the buyer

The buyer's assumption of the seller's existing nonrecourse debt on the property

The buyer's assumption of all recourse debt on the property with the complete release of the seller from those obligations

Any combination of such cash and debt assumption

Even if the required down payment is made, a number of factors must be considered by the seller in connection with a receivable from the buyer. They include:

Collectibility of the receivable

Buyer's continuing investment—amortization of receivable

Future subordination

Release provisions

Imputation of interest

Collectibility of the receivable must be reasonably assured and should be assessed in light of factors such as the credit standing of the buyer (if recourse), cash flow from the property, and the property's size and geographical location. This requirement may be particularly important when the receivable is relatively short term and collectibility is questionable because the buyer will be required to obtain financing. Furthermore, a basic principle of real estate sales on credit is that the receivable must be adequately secured by the property sold.

Continuing investment requirements for full profit recognition require that the buyer's payments on its total debt for the purchase price must be at least equal to level annual payments (including principal and interest) based on amortization of the full amount over a maximum term of 20 years for land and over the customary term of a first mortgage by an independent established lending institution for other property. The annual payments must begin within one year of recording the sale and, to be acceptable, must meet the same composition test as used in determining adequacy of down payments. The customary term of a first mortgage loan is usually considered to be the term of a new loan (or the term of an existing loan placed in recent years) from an independent financial lending institution.

All indebtedness on the property need not be reduced proportionately. However, if the seller's receivable is not being amortized, realization may be in question and the collectibility must be more carefully assessed. Lump-sum (balloon) payments do not affect the amortization requirement as long as the scheduled amortization is within the maximum period and the minimum annual amortization tests are met.

For example, if the customary term of the mortgage by an independent lender required amortizing payments over a period of 25 years, then the continuing investment requirement would be based on such an amortization schedule. If the terms of the receivable required principal and interest payments on such a schedule only for the first five years with a balloon at the end of year 5, the continuing investment requirements are met. In such cases, however, the collectibility of the balloon payment should be carefully assessed.

If the amortization requirements for full profit recognition as set forth above are not met, a reduced profit may be recognized by the seller if the annual payments are at least equal to the total of:

Annual level payments of principal and interest on a maximum available first mortgage

Interest at an appropriate rate on the remaining amount payable by the buyer

The reduced profit is determined by discounting the receivable from the buyer to the present value of the lowest level of annual payments required by the sales contract excluding requirements to pay lump sums. The present value is calculated using an appropriate interest rate, but not less than the rate stated in the sales contract.

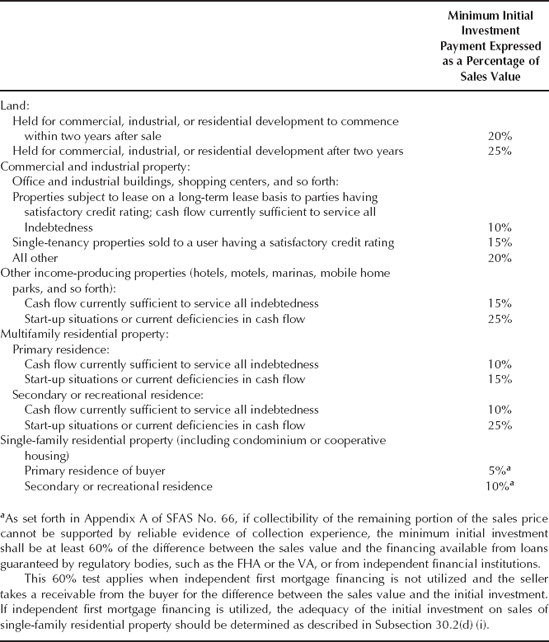

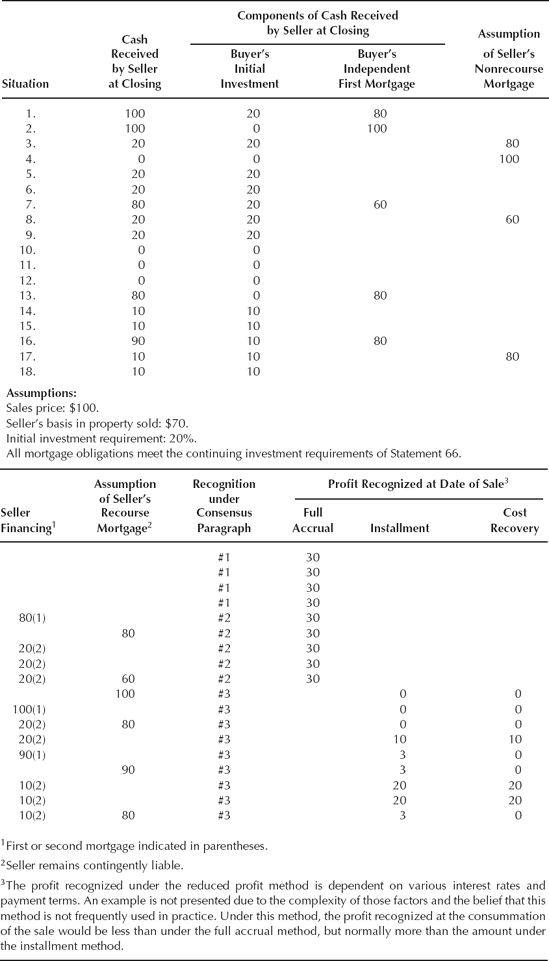

The amount calculated would be used as the value of the receivable for the purpose of determining the reduced profit. The calculation of reduced profit is illustrated in Exhibit 30.3

The requirements for amortization of the receivable are applied cumulatively at the closing date (date of recording the sale for accounting purposes) and annually thereafter. Any excess of down payment received over the minimum required is applied toward the amortization requirements.

If the receivable is subject to future subordination to a future loan available to the buyer, profit recognition cannot exceed the amount determined under the cost recovery method (see Subsection 30.2(j)(iii)) unless proceeds of the loan are first used to reduce the seller's receivable. Although this accounting treatment is controversial, the cost recovery method is required because collectibility of the sales price is not reasonably assured. The future subordination would permit the primary lender to obtain a prior lien on the property, leaving only a secondary residual value for the seller, and future loans could indirectly finance the buyer's initial cash investment. Future loans would include funds received by the buyer arising from a permanent loan commitment existing at the time of the transaction unless such funds were first applied to reduce the seller's receivable as provided for in the terms of the sale.

The cost recovery method is not required if the receivable is subordinate to a previous mortgage on the property existing at the time of sale.

Some sales transactions have provisions releasing portions of the property from the liens securing the debt as partial payments are made. In this situation, full profit recognition is acceptable only if the buyer must make, at the time of each release, cumulative payments that are adequate in relation to the sales value of property not released.

Careful attention should be given to the necessity for imputation of interest under Accounting Principles BoardAccounting Principles Board (APB) Opinion No. 21, "Interest on Receivables and Payables," since it could have a significant effect on the amount of profit or loss recognition. As stated in the first paragraph of APB Opinion No. 21: "The use of an interest rate that varies from prevailing interest rates warrants evaluation of whether the face amount and the stated interest rate of a note or obligation provide reliable evidence for properly recording the exchange and subsequent related interest."

If imputation of interest is necessary, the mortgage note receivable should be adjusted to its present value by discounting all future payments on the notes using an imputed rate of interest at the prevailing rates available for similar financing with independent financial institutions. A distinction must be made between first and second mortgage loans because the appropriate imputed rate for a second mortgage would normally be significantly higher than the rate for a first mortgage loan. It may be necessary to obtain independent valuations to assist in the determination of the proper rate.

If the criteria for recording a sale have been met but the tests related to the collectibility of the receivable as set forth herein are not met, the accrual method of accounting is not appropriate and the installment or cost recovery method of accounting should be used. These methods are discussed in Subsection 30.2(j) of this chapter.

A seller sometimes continues to be involved over long periods of time with property legally sold. This involvement may take many forms such as participation in future profits, financing, management services, development, construction, guarantees, and options to repurchase. With respect to profit recognition when a seller has continued involvement, the two key principles are as follows:

A sales contract should not be accounted for as a sale if the seller's continued involvement with the property includes the same kinds of risk as does ownership of property.

Profit recognition should follow performance and in some cases should be postponed completely until a later date.

A sale of real estate may include or be accompanied by an agreement that provides for the seller to participate in future operating profits or residual values. As long as the seller has no further obligations or risk of loss, profit recognition on the sale need not be deferred. A receivable from the buyer is permitted if the other tests for profit recognition are met, but no costs can be deferred.

If the seller has an option or obligation to repurchase property (including a buyer's option to compel the seller to repurchase), a sale cannot be recognized (SFAS No. 66, par. 26). However, neither a commitment by the seller to assist or use his best efforts (with appropriate compensation) on a resale nor a right of first refusal based on a bona fide offer by a third party would preclude sale recognition. The accounting to be followed depends on the repurchase terms. EITF Consensus No. 86-6 discusses accounting for a sale transaction when antispeculation clauses exist. A consensus was reached that the contingent option would not preclude sale recognition if the probability of buyer noncompliance is remote.

When the seller has an obligation or an option that is reasonably expected to be exercised to repurchase the property at a price higher than the total amount of the payments received and to be received, the transaction is a financing arrangement and should be accounted for under the financing method. If the option is not reasonably expected to be exercised, the deposit method is appropriate.

In the case of a repurchase obligation or option at a lower price, the transaction usually is, in substance, a lease or is part lease, part financing and should be accounted for under the lease method. Where an option to repurchase is at a market price to be determined in the future, the transaction should be accounted for under the deposit method or the profit-sharing method.

When the seller is a general partner in a limited partnership and has a significant receivable related to the property, the transaction would not qualify as a sale. It should usually be accounted for as a profit-sharing arrangement. A significant receivable is one that is in excess of 15 percent of the maximum first lien financing that could be obtained from an established lending institution for the property sold.

The buyer's investment in the property cannot be evaluated until adequate permanent financing at an acceptable cost is available to the buyer. If the seller must obtain or provide this financing, obtaining the financing is a prerequisite to a sale for accounting purposes. Even if not required to do so, the seller may be presumed to have such an obligation if the buyer does not have financing and the collectibility of the receivable is questionable. The deposit method is appropriate if lack of financing is the only impediment to recording a sale.

SFAS No. 66 (par. 28) states: "If the seller guarantees return of the buyer's investment, ... the transaction shall be accounted for as a financing, leasing, or profit-sharing arrangement."

Accordingly, if the terms of a transaction are such that the buyer may expect to recover the initial investment through assured cash returns, subsidies, and net tax benefits, even if the buyer were to default on debt to the seller, the transaction is probably not in substance a sale.

When the seller guarantees cash returns on the buyer's investment, the accounting method to be followed depends on whether the guarantee is for an extended or limited period and whether the seller's expected cost of the guarantee is determinable.

SFAS No. 66 states that when the seller contractually guarantees cash returns on investments to the buyer for an extended period, the transaction should be accounted for as a financing, leasing, or profit-sharing arrangement. An "extended period" was not defined but should at least include periods that are not limited in time or specified lengthy periods, such as more than five years.

If the guarantee of a return on the buyer's investment is for a limited period, SFAS No. 66 indicates that the deposit method of accounting should be used until such time as operation of the property covers all operating expenses, debt service, and contractual payments. At that time, profit should be recognized based on performance (see Subsection 30.2(j)). A "limited period" was not defined but is believed to relate to specified shorter periods, such as five years or less.

Irrespective of the above, if the guarantee is determinable or limited, sale and profit recognition may be appropriate if reduced by the maximum exposure to loss as described below.

If the amount can be reasonably estimated, the seller should record the guarantee as a cost at the time of sale, thus either reducing the profit or increasing the loss on the transaction.

If the amount cannot be reasonably estimated, the transaction is probably in substance a profit-sharing or co-venture arrangement.

If the amount cannot be reasonably estimated but a maximum cost of the guarantee is determinable, the seller may record the maximum cost of the guarantee as a cost at the time of sale, thus either reducing the profit or increasing the loss on the transaction. Alternatively, the seller may account for the transaction as if the guarantee amount is not determinable. Implications of a seller's guarantee of cash flow on an operating property that is not considered a sale-leaseback arrangement are discussed in Subsection 30.2(f)(x).

A guarantee of cash flow to the buyer sometimes takes the form of a leaseback arrangement. Since the earnings process in this situation has not usually been completed, profits on the sale should generally be deferred and amortized.

Accounting for a sale-leaseback of real estate is governed by SFAS No. 13, "Accounting for Leases," as amended by SFAS No. 28, "Accounting for Sales with Leasebacks," SFAS No. 98, "Accounting for Leases: Sale-Leaseback Transactions Involving Real Estate," and SFAS No. 66. SFAS No. 98 specifies the accounting by a seller-lessee for a sale-leaseback transaction involving real estate, including real estate with equipment. SFAS No. 98 provides that:

A sale-leaseback transaction involving real estate, including real estate with equipment, must qualify as a sale under the provisions of SFAS No. 66 as amended by SFAS No. 98, before it is appropriate for the seller-lessee to account for the transaction as a sale. If the transaction does not qualify as a sale under SFAS No. 66, it should be accounted for by the deposit method or as a financing transaction (see Subsection 30.2(j)(v)).

A sale-leaseback transaction involving real estate, including real estate with equipment, that includes any continuing involvement other than a normal leaseback in which the seller-lessee intends to actively use the property during the lease should be accounted for by the deposit method or as a financing transaction.

A lease involving real estate may not be classified as a sales-type lease unless the lease agreement provides for the transfer of title to the lessee at or shortly after the end of the lease term. Sales-type leases involving real estate should be accounted for under the provisions of SFAS No. 66.

Profits should be deferred and amortized in a manner consistent with the classification of the leaseback:

If the leaseback is an operating lease, deferred profit should be amortized in proportion to the related gross rental charges to expense over the lease term.

If the leaseback is a capital lease, deferred profit should be amortized in proportion to the amortization of the leased asset. Effectively, the sale is treated as a financing transaction. The deferred profit can be presented gross, but normally is offset against the capitalized asset for balance sheet classification purposes.

In situations where the leaseback covers only a minor portion of the property sold or the period is relatively minor compared to the remaining useful life of the property, it may be appropriate to recognize all or a portion of the gain as income. Sales with minor leasebacks should be accounted for based on the separate terms of the sale and the leaseback unless the rentals called for by the leaseback are unreasonable in relation to current market conditions. If rentals are considered to be unreasonable, they must be adjusted to a reasonable amount in computing the profit on the sale.

The leaseback is considered to be minor when the present value of the leaseback based on reasonable rentals is 10 percent or less of the fair value of the asset sold. If the leaseback is not considered to be minor (but less than substantially all of the use of the asset is retained through a leaseback) profit may be recognized to the extent it exceeds the present value of the minimum lease payments (net of executory costs) in the case of an operating lease or the recorded amount of the leased asset in the case of a capital lease.

Losses should be recognized immediately to the extent that the undepreciated cost (net carrying value) exceeds the fair value of the property. Fair value is frequently determined by the selling price from which the loss on the sale is measured. Many sale-leasebacks are entered into as a means of financing, or for tax reasons, or both. The terms of the leaseback are negotiated as a package. Because of the interdependence of the sale and concurrent leaseback, the selling price in some cases is not representative of fair value. It would not be appropriate to recognize a loss on the sale that would be offset by future cost reductions as a result of either reduced rental costs under an operating lease or depreciation and interest charges under a capital lease. Therefore, to the extent that the fair value is greater than the sale price, losses should be deferred and amortized in the same manner as profits.

A sales contract may be accompanied by an agreement for the seller to provide management or other services without adequate compensation. Compensation for the value of the services should be imputed, deducted from the sales price, and recognized over the term of the contract. See discussion of implied support of operations in Subsection 30.2(f)(x) if the contract is noncancelable and the compensation is unusual for the services to be rendered.

A sale of undeveloped or partially developed land may include or be accompanied by an agreement requiring future seller performance of development or construction. In such cases, all or a portion of the profit should be deferred. If there is a lapse of time between the sale agreement and the future performance agreement, deferral provisions usually apply if definitive development plans existed at the time of sale and a development contract was anticipated by the parties at the time of entering into the sales contract.

In addition, SFAS No. 66 (par. 41) provides that "The seller is involved with future development or construction work if the buyer is unable to pay amounts due for that work or has the right under the terms of the arrangement to defer payment until the work is done."

If the property sold and being developed is an operating property (such as an apartment complex, shopping center, or office building) as opposed to a nonoperating property (such as a land lot, condominium unit, or single-family detached home), Subsection 30.2(f)(x) may also apply.

If a seller is obligated to develop the property or construct facilities and total costs and profit cannot be reliably estimated (e.g., because of lack of seller experience or nondefinitive plans), all profit, including profit on the sale of land, should be deferred until the contract is completed or until the total costs and profit can be reliably estimated. Under the completed contract method, all profit, including profit on the sale of land, is deferred until the seller's obligations are fulfilled.

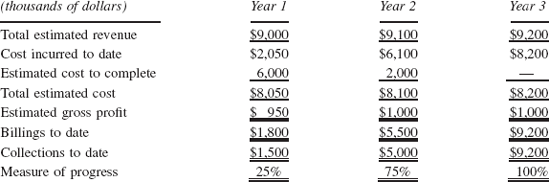

If the costs and profit can be reliably estimated, profit recognition over the improvement period on the basis of costs incurred (including land) as a percentage of total costs to be incurred is required. Thus, if the land was a principal part of the sale and its market value greatly exceeded cost, part of the profit that can be said to be related to the land sale is deferred and recognized during the development or construction period.

The same rate of profit is used for all seller costs connected with the transaction. For this purpose, the cost of development work, improvements, and all fees and expenses that are the responsibility of the seller should be included. The buyer's initial and continuing investment tests, of course, must be met with respect to the total sales value. Exhibit 30.4 illustrates the cost incurred method.

If the property sold is an operating property, as opposed to a nonoperating property, deferral of all or a portion of the profit may be required under SFAS No. 66 (pars. 28– 30). These paragraphs establish guidelines not only for stated support but also for implied support.

Although the implied support provisions do not usually apply to undeveloped or partially developed land, they do apply if the buyer has commitments to construct operating properties and there is stated or implied support.

Assuming that the criteria for recording a sale and the test of buyer's investment are met, the following sets forth guidelines for profit recognition where there is stated or implied support.

A seller may be required to support operations by means of a guaranteed return to the buyer. Alternatively, a guarantee may be made to the buyer that there will be no negative cash flow from the project, buy may not guarantee a positive return on the buyer's investment. For example, EITF Consensus No. 85-27 "Recognition of Receipts from Made-Up Rental Shortfalls," considers the impact of a master lease guarantee. The broad exposure that such a guarantee creates has a negative impact on profit recognition.

The seller may be presumed to be obligated to initiate and support operations of the property sold, even in the absence of specified requirements in the sale contract or related document. The following conditions under which support is implied are described in footnote 10 of SFAS No. 66:

A seller obtains an interest as general partner in a limited partnership that acquires an interest in the property sold.

A seller retains an equity interest in the property, such as an undivided interest or an equity interest in a joint venture that holds an interest in the property.

A seller holds a receivable from a buyer for a significant part of the sales price and collection of the receivable is dependent on the operation of the property.

A seller agrees to manage the property for the buyer on terms not usual for the services to be rendered and which is not terminable by either seller or buyer.

When profit recognition is appropriate in the case of either stated or implied support, the following general rules apply:

Profit is recognized on the ratio of costs incurred to total costs to be incurred. Revenues for gross profit purposes include rent from operations during the rent-up period; costs include land and operating expenses during the rent-up period as well as other costs.

As set forth in SFAS No. 66 (par. 30):

[S]upport shall be presumed for at least two years from the time of initial rental unless actual rental operations cover operating expenses, debt service, and other contractual commitments before that time. If the seller is contractually obligated for a longer time, profit recognition shall continue on the basis of performance until the obligation expires.

Estimated rental income should be adjusted by reducing estimated future rent receipts by a safety factor of 33⅓ percent unless signed lease agreements have been obtained to support a projection higher than the rental level thus computed. As set forth in SFAS No. 66 (par. 29), when signed leases amount to more than 66

A partial sale includes the following:

A sale of an interest in real estate

A sale of real estate where the seller has an equity interest in the buyer (e.g., a joint venture or partnership)

A sale of a condominium unit

Except for operating properties, profit recognition is appropriate in a sale of a partial interest if all the following conditions exist:

Sale is to an independent buyer.

Collection of sales price is reasonably assured.

The seller will not be required to support the property, its operations, or related obligations to an extent greater than its proportionate interest.

Buyer does not have preferences as to profits or cash flow. (If the buyer has such preferences, the cost recovery method is required.)

In the case of a sale of a partial interest in operating properties, if the conditions set forth in the preceding paragraph are met, profit recognition must reflect an adjustment for the implied presumption that the seller is obligated to support the operations.

No profit may be recognized if the seller controls the buyer. If seller does not control the buyer, profit recognition (to the extent of the other investors' proportionate interests) is appropriate if all other necessary requirements for profit recognition are satisfied. The portion of the profit applicable to the equity interest of the seller/investor should be deferred until such costs are charged to operations by the venture. Again, with respect to a sale of operating properties, a portion of the profit relating to other investors' interests may have to be spread as described in Subsection 30.2(f)(x) because there is an implied presumption that the seller is obligated to support the operations.

Although the definition of "condominium" varies by state, the term generally is defined as a multiunit structure in which there is fee simple title to individual units combined with an undivided interest in the common elements associated with the structure. The common elements are all areas exclusive of the individual units, such as hallways, lobbies, and elevators.

A cooperative is contrasted to a condominium in that ownership of the building is generally vested in the entity, with the respective stockholders of the entity having a right to occupy specific units. Operation, maintenance, and control of the building are exercised by a governing board elected by the owners. This section covers only sales of condominium units.

The general principles of accounting for profit on sales of condominiums are essentially those previously discussed for sales of real estate in general. The following criteria must be met prior to recognition of any profit on the sale of a dwelling unit in a condominium project:

All parties must be bound by the terms of the contract. For the buyer to be bound, the buyer must be unable to require a refund. Certain state and federal laws require appropriate filings by the developer before the sales contract is binding; otherwise, the sale may be voidable at the option of the buyer.

All conditions precedent to closing, except completion of the project, must be performed.

An adequate cash down payment must be received by the seller. The minimum down payment requirements are 5 percent for a primary residence and 10 percent for a secondary or recreational residence.

The buyer must be required to adequately increase the investment in the property annually; the buyer's commitment must be adequately secured. Typically, a condominium buyer pays the remaining balance from the proceeds of a permanent loan at the time of closing. If, however, the seller provides financing, the same considerations as other sales of real estate apply concerning amortization of the buyer's receivable.

The developer must not have an option or obligation to repurchase the property.

Sales of condominium units are accounted for by using the closing (completed contract) method or the percentage of completion method. Most developers use the closing method.

Additional criteria must be met for the use of the percentage of completion method:

The developer must have the ability to estimate costs not yet incurred.

Construction must be beyond a preliminary stage of completion. This generally means at least beyond the foundation stage.

Sufficient units must be sold to assure that the property will not revert to rental property.

The developer must be able to reasonably estimate aggregate sales proceeds.

This method involves recording the sale and related profit at the time a unit closes. Since the unit is completed, actual costs are used in determining profit to be recognized.

All payments or deposits received prior to closing are accounted for as a liability. Direct selling costs may be deferred until the sale is recorded. Where the seller is obligated to complete construction of common areas or has made guarantees to the condominium association, profit should be recognized based on the relationship of costs already incurred to total estimated costs, with a portion deferred until the future performance is completed.

This method generally involves recording sales at the date a unit is sold and recognizing profit on units sold as construction proceeds. As a result, this method allows some profit recognition during the construction period. Although dependent on estimates, this method may be considered preferable for some long-term projects. A lack of reliable estimates, however, would preclude the use of this method.

Profit recognition is based on the percentage of completion of the project multiplied by the gross profit arising from the units sold. Percentage of completion may be determined by using either of the following alternatives:

The ratio of costs incurred to date to total estimated costs to be incurred. These costs could include land and common costs or could be limited to construction costs. The costs selected for inclusion should be those that most clearly reflect the earnings process.

The percentage of completed construction based on architectural plans or engineering studies.

Under either method of accounting, if the total estimated costs exceed the estimated proceeds, the total anticipated loss should be charged against income in the period in which the loss becomes evident so that no anticipated losses are deferred to future periods. See further discussion of this method in Section 30.6, "Construction Contracts."

As previously mentioned, future costs to complete must be estimated under either the closing method or the percentage of completion method. Estimates of future costs to complete are necessary to determine net realizable value of unsold units. Estimated future costs should be based on adequate architectural and engineering studies and should include reasonable provisions for:

Unforeseen costs in accordance with sound cost estimation practices

Anticipated cost inflation in the construction industry

Costs of offsite improvements, utility facilities, and amenities (to the extent that they will not be recovered from outside third parties)

Operating losses of utility operations and recreational facilities (Such losses would be expected to be incurred for a relatively limited period of time—usually prior to sale of facilities or transfer to some public authority.)

Other guaranteed support arrangements or activities to the extent that they will not be recovered from outside parties or be the responsibility of a future purchaser

Estimates of amounts to be recovered from any sources should be discounted to present value as of the date the related costs are expected to be incurred.

Estimated costs to complete and the allocation of such costs should be reviewed at the end of each financial reporting period, with costs revised and reallocated as necessary on the basis of current estimates, as recommended in SFAS No. 67, "Accounting for Costs and Initial Rental Operations of Real Estate Projects." How to record the effects of changes in estimates depends on whether full revenues have been recorded or whether reporting of the revenue has been deferred due to an obligation for future performance or otherwise.

When sales of condominiums are recorded in full, it may be necessary to accrue certain estimated costs not yet incurred and also related profit thereon. Adjustments of accruals for costs applicable to such previously recognized sales, where deferral for future performance was not required, must be recognized and charged to costs of sales in the period in which they become known. See Subsection 30.2(g)(ii) for further discussion.

In many cases, sales are not recorded in full (such as when the seller has deferred revenue because of an obligation for future performance to complete improvements and amenities of a project). In these situations, the adjustments should not affect previously recorded deferred revenues applicable to future improvements but should be recorded prospectively in the current and future periods. An increase in the estimate of costs applicable to deferred revenues will thus result in profit margins lower than those recorded on previous revenues from the project.

An exception exists, however, when the revised total estimated costs exceed the applicable deferred revenue. If that occurs, the total anticipated loss should be charged against income in the period in which the need for adjustment becomes evident.

In addition, an increase in estimated costs to complete without comparable increases in market value could raise questions as to whether the estimated total costs of the remaining property exceed the project's net realizable value.

APB Opinion No. 20, "Accounting Changes," has been interpreted to permit both the cumulative catch-up method and the prospective method of accounting for changes in accounting estimates. It should be noted that SFAS No. 67 (pars. 42–43) requires the prospective method.

Retail land sales, a unique segment of the real estate industry, is the retail marketing of numerous lots subdivided from a larger parcel of land. The relevant accounting guidance originally covered by the AICPA Industry Accounting Guide, "Accounting for Retail Land Sales," and now included in SFAS No. 66, applies to retail lot sales on a volume basis with down payments that are less than those required to evaluate the collectibility of casual sales of real estate. Wholesale or bulk sales of land and retail sales from projects comprising a small number of lots, however, are subject to the general principles for profit recognition on real estate sales.

Sales should not be recorded until:

The customer has made all required payments and the period of cancellation with refund has expired.

Aggregate payments (including interest) equal or exceed 10 percent of contract sales price.

The selling company is clearly capable of providing land improvements and offsite facilities promised as well as meeting all other representations it has made.

If these conditions are met, either the accrual or the installment method must be used. If the conditions are not met, the deposit method of accounting should be used.

The following tests for the use of accrual method should be applied on a project-by-project basis:

The seller has fulfilled the obligation to complete improvements and to construct amenities or other facilities applicable to the lots sold.

The receivable is not subject to subordination to new loans on the property, except subordination for home construction purposes under certain conditions.

The collection experience for the project indicates that collectibility of receivable balances is reasonably predictable and that 90 percent of the contracts in force six months after sales are recorded will be collected in full. A down payment of at least 20 percent shall be an acceptable indication of collectibility.

To predict collection results of current sales, there must be satisfactory experience on prior sales of the type of land being currently sold in the project. In addition, the collection period must be sufficiently long to allow reasonable estimates of the percentage of sales that will be fully collected. In a new project, the developers' experience on prior projects may be used if they have demonstrated an ability to successfully develop other projects with the same characteristics (environment, clientele, contract terms, sales methods) as the new project.

Collection and cancellation experience within a project may differ with varying sales methods (such as telephone, broker, and site visitation sales). Accordingly, historical data should be maintained with respect to each type of sales method used.

Unless all conditions for use of the accrual method are met for the entire project, the installment method of accounting should be applied to all recorded sales of the project.

Revenues and costs should be accounted for under the accrual method as follows:

The contract price should be recorded as gross sales.

Receivables should be discounted to reflect an appropriate interest rate using the criteria established in APB Opinion No. 21.

An allowance for contract cancellation should be recorded and deducted from gross sales to derive net sales.

Cost of sales should be calculated based on net sales after reductions for sales reasonably expected to cancel.

Frequently, the conditions for use of the accrual method are met, except the seller has not yet completed the improvements, amenities, or other facilities required by the sales contract. In this situation the percentage of completion method should be applied provided both of the following conditions are met:

There is a reasonable expectation that the land can be developed for the purposes represented.

The project's improvements have progressed beyond preliminary stages, and there are indications that the work will be completed according to plan. Indications that the project has progressed beyond the preliminary stage include the following:

Funds for the proposed improvements have been expended.

Work on the improvements has been initiated.

Engineering plans and work commitments exist relating to the lots sold.

Access roads and amenities such as golf courses, clubhouses, and swimming pools have been completed.

In addition, there shall be no indication of significant delaying factors such as the inability to obtain permits, contractors, personnel, or equipment, and estimates of costs to complete and extent of progress toward completion shall be reasonably dependable.

The following general procedures should be used to account for revenues and costs under the percentage of completion method of accounting:

The amount of revenue recognized (discounted where appropriate pursuant to APB Opinion No. 21) is based on the relationship of costs already incurred to the total estimated costs to be incurred.

Costs incurred and to be incurred should include land, interest and project carrying costs incurred prior to sale, selling costs, and an estimate for future improvement costs.

Estimates of future improvement costs should be reviewed at least annually. Changes in those estimates do not lead to adjustment of deferred revenue applicable to future improvements that has been previously recorded unless the adjusted total estimated costs exceeds the applicable revenue. When cost estimates are revised, the relationship of the two elements included in the revenue not yet recognized—cost and profit—should be recalculated on a cumulative basis to determine future income recognition as performance takes place. If the adjusted total estimated cost exceeds the applicable deferred revenue, the total anticipated loss should be charged to income. When anticipated losses on lots sold are recognized, the enterprise should also consider recognizing a loss on land and improvements not yet sold.

Future performance costs such as roads, utilities, and amenities may represent a significant obligation for a retail land developer. Estimates of such costs should be based on adequate engineering studies, appropriately adjusted for anticipated inflation in the local construction industry, and should include reasonable estimates for unforeseen costs.

If the criteria for the accrual or percentage of completion methods are not satisfied, the installment or deposit method may be used. See Subsection 30.2(j) for a general discussion of these methods.

When the conditions required for use of the percentage of completion method are met on a project originally recorded under the installment method, the percentage of completion method of accounting should be adopted for the entire project (current and prior sales). The effect should be accounted for as a change in accounting estimate due to different circumstances. See Subsection 30.2(g)(iii) for further discussion of methodology.

On February 6, 1992, the AICPA issued Statement of PositionStatement of Position (SOP) 92-1, which provides guidance on accounting for real estate syndication income.

Syndicators expect to earn fees and commissions from a variety of sources: up-front fees such as lease-up fees, construction supervision fees, and financing fees; fees serving as an incentive; property management; participation in future profit or appreciation. At the time of the syndication, partnerships usually pay cash to the syndicator for portions of their up-front fees. These fees are usually paid from investor contributions or the proceeds of borrowings. Subsequent fees are expected to be paid from operations, refinancings, sale of property, or remaining investor payments.

The SOP states that SFAS No. 66 applies to the recognition of profit on the sales of real estate by syndicators to partnerships. It concludes that profit on real estate syndication transactions be accounted for in accordance with SFAS No. 66, even if the syndicator never had ownership interests in the properties acquired by the real estate partnerships.

The SOP states that fees charged by syndicators (except for syndication fees and fees for future services) should be included in the determination of "sales value" in conformity with SFAS No. 66. It further states that SFAS No. 66 does not apply to the fees excluded from "sales value." Fees for future services should be recognized when the earning process is complete and collection of the fee is reasonably assured.

This SOP requires that income recognition on syndication fees and fees for future services be deferred if the syndicator is exposed to future losses or costs from material involvement with the properties, partnerships or partners, or uncertainties regarding the collectibility of partnership notes. The income should be deferred until the losses or costs can be reasonably estimated.

The SOP requires that for the purpose of determining whether buyers' initial and continuing investments satisfy the requirements for recognizing full profit in accordance with SFAS No. 66, cash received by syndicators should be allocated to unpaid syndication fees before being allocated to the initial and continuing investment. After the syndication fee is fully paid, additional cash received should first be allocated to unpaid fees for future services, to the extent those services have been performed by the time the cash is received, before being allocated to the initial and continuing investment.

As previously discussed, in some circumstances the accrual method is not appropriate and other methods must be used. It is not always clear which method should be used or how it should be applied. Consequently, it is often difficult to determine the appropriate method and whether alternative ones are acceptable.

The methods prescribed where the buyer's initial or continuing investment is inadequate are the deposit, installment, cost recovery, and reduced profit methods.

The methods prescribed for a transaction that cannot be considered a sale because of the seller's continuing involvement are the financing, lease, and profit sharing (or co-venture) methods.

When the substance of a real estate transaction indicates that a sale has not occurred, for accounting purposes, as a result of the buyer's inadequate investment, recognition of the sale should be deferred and the deposit method used. This method should be continued until the conditions requiring its use no longer exist. For example, when the down payment is so small that the substance of the transaction is an option arrangement, the sale should not be recorded.

All cash received under the deposit method (including down payment and principal and interest payments by the buyer to the seller) should be reported as a deposit (liability). An exception is interest received that is not subject to refund may appropriately offset carrying charges (property taxes and interest on existing debt) on the property. Note also the following related matters:

Notes receivable arising from the transaction should not be recorded.

The property and any related mortgage debt assumed by the buyer should continue to be reflected on the seller's balance sheet, with appropriate disclosure that such properties and debt are subject to a sales contract. Even nonrecourse debt assumed by the buyer should not be offset against the related property.

Subsequent payments on the debt assumed by the buyer become additional deposits and thereby reduce the seller's mortgage debt payable and increase the deposit liability account until a sale is recorded for accounting purposes.

Depreciation should be continued.

Under the deposit method, a sale is not recorded for accounting purposes until the conditions in SFAS No. 66 are met. Therefore, for purposes of the down payment tests, interest received and credited to the deposit account can be included in the down payment and sales value at the time a sale is recorded.

If a buyer defaults and forfeits his nonrefundable deposit, the deposit liability is no longer required and may be credited to income. The circumstances underlying the default should be carefully reviewed since such circumstances may indicate deteriorating value of the property. In such a case it may be appropriate to treat the credit as a valuation reserve. These circumstances may require a provision for additional loss. See Section 30.5 for further discussion.

When the substance of a real estate transaction indicates that a sale has occurred for accounting purposes, but that collectibility of the total sales price cannot be reasonably estimated (i.e., inadequate buyer's investment), the installment method may be appropriate. However, circumstances may indicate that the cost recovery method is required or is otherwise more appropriate. For example, when the deferred gross profit exceeds the net carrying value of the related receivable, profit may have been earned to the extent of such excess.

Profit should be recognized on cash payments, including principal payments by the buyer on any debt assumed (either recourse or nonrecourse), and should be based on the ratio of total profit to total sales value (including a first mortgage debt assumed by the buyer, if applicable). Interest received on the related receivable is properly recorded as income when received.

The total sales value (from which the deferred gross profit should be deducted) and the cost of sales should be presented in the income statement. Deferred gross profit should be shown as a deduction from the related receivable, with subsequent income recognition presented separately in the income statement.

The cost recovery method must be used when the substance of a real estate transaction indicates that a sale has occurred for accounting purposes but no profit should be recognized until costs are recovered. This may occur when (1) the receivable is subject to future subordination, (2) the seller retains an interest in the property sold and the buyer has preferences, (3) uncertainty exists as to whether all or a portion of the cost will be recovered, or (4) there is uncertainty as to the amount of proceeds. As a practical matter, the cost recovery method can always be used as an alternative to the installment method.

Under the cost recovery method, no profit is recognized until cash collections (including principal and interest payments) and existing debt assumed by the buyer exceed the cost of the property sold. Cash collections in excess of cost should be recorded as revenue in the period of collection.

Financial statement presentation under the cost recovery method is similar to that for the installment method.

When the substance of a real estate transaction indicates that a sale has occurred for accounting purposes, but the continuing investment criteria for full profit recognition is not met by the buyer, the seller may sometimes recognize a reduced profit at the time of sale (see additional discussion in Subsection 30.2(e)(ii)). This alternative is rarely used since a full accrual of anticipated costs of continuing investment will permit full accrual of the remaining profit.

A real estate transaction may be, in substance, a financing arrangement rather than a sale. This is frequently the case when the seller has an obligation to repurchase the property (or can be compelled by the buyer to repurchase the property) at a price higher than the total amount of the payments received and to be received. In such a case the financing method must be used.

Accounting procedures under the financing method should be similar to the accounting procedures under the deposit method, with one exception. Under the financing method, the difference between (1) the total amount of all payments received and to be received and (2) the repurchase price is presumed to be interest expense. As such, it should be accrued on the interest method over the period from the receipt of cash to the date of repurchase. As in the deposit method, cash received is reflected as a liability in the balance sheet. Thus, at the date of repurchase, the full amount of the repurchase obligation should be recorded as a liability.

In the case of a repurchase option, if the facts and circumstances at the time of the sale indicate a presumption or a likelihood that the seller will exercise the option, interest should be accrued as if there were an obligation to repurchase. This presumption could result from the value of the property, the property being an integral part of development, or from management's intention. If such a presumption does not exist at the time of the sale transaction, interest should not be accrued and the deposit method is appropriate.

A real estate transaction may be, in substance, a lease rather than a sale. Accounting procedures under the lease method should be similar to the deposit method, except as follows:

Payments received and to be received that are in substance deferred rental income received in advance should be deferred and amortized to income over the presumed lease period. Such amortization to income should not exceed cash paid to the seller.

Cash paid out by the seller as a guarantee of support of operations should be expensed as paid.

The seller may agree to make loans to the buyer in support of operations, for example, when cash flow does not equal a predetermined amount or is negative. In such a situation, deferred rental income to be amortized to income should be reduced by all the loans made or reasonably anticipated to be made to the buyer, thus reducing the periodic income to be recognized. Where the loans made or anticipated exceed deferred rental income, a loss provision may be required if the collectibility of the loan is questionable.

A real estate transaction may be, in substance, a profit-sharing arrangement rather than a sale. For example, a sale of real estate to a limited partnership in which the seller is a general partner or has similar characteristics is often a profit-sharing arrangement. If such a transaction does not meet the tests for recording a sale, it usually would be accounted for under the profit-sharing method. This accounting method should also be followed when it is clear that the buyer is acting merely as an agent for the seller.

Under the profit-sharing method, giving consideration to the seller's continued involvement, the seller would be required to account for the operations of the property through its income statement as if it continued to own the properties.

In October 1982, the FASB issued SFAS No. 67. This Statement incorporates the specialized accounting principles and practices from the AICPA SOPs No. 80-3, "Accounting for Real Estate Acquisition, Development and Construction Costs," and No. 78-3, "Accounting for Costs to Sell and Rent, and Initial Rental Operations of Real Estate Projects," and those in the AICPA Industry Accounting Guide, "Accounting for Retail Land Sales," that address costs of real estate projects. SFAS No. 67 establishes whether costs associated with acquiring, developing, constructing, selling, and renting real estate projects should be capitalized. Guidance is also provided on the appropriate methods of allocating capitalized costs to individual components of the project.

SFAS No. 67 also established that a rental project changes from nonoperating to operating when it is substantially completed and held available for occupancy, but not later than one year from cessation of major construction activities.

What are the general precepts? Costs incurred in real estate operations range from brick-and-mortar costs that clearly should be capitalized to general administrative costs that clearly should not be capitalized. Between these two extremes lies a broad range of costs that are difficult to classify. Therefore, judgmental decisions must be made as to whether such costs should be capitalized.

These costs include payments to obtain options to acquire real property and other costs incurred prior to acquisition such as legal, architectural, and other professional fees, salaries, environmental studies, appraisals, marketing and feasibility studies, and soil tests. Capitalization of costs related to a property that are incurred before the enterprise acquires the property, or before the enterprise obtains an option to acquire it, is appropriate provided all of the following conditions are met:

The costs are directly identifiable with the specific property.

The costs would be capitalized if the property had already been acquired.

Acquisition of the property or of an option to acquire the property is probable (i.e., likely to occur). This condition requires that the prospective purchaser is actively seeking acquisition of the property and has the ability to finance or obtain financing for the acquisition. In addition, there should be no indication that the property is not available for sale.

Capitalized preacquisition costs should be included as project costs on acquisition of the property or should be charged to expense when it is probable that the property will not be acquired. The charge to expense should be reduced by the amount recoverable by the sale of the options, plans, and so on.

Costs directly related to the acquisition of land should be capitalized. These costs include option fees, purchase cost, transfer costs, title insurance, legal and other professional fees, surveys, appraisals, and real estate commissions. The purchase cost may have to be increased or decreased for imputation of interest on mortgage notes payable assumed or issued in connection with the purchase, as required under APB Opinion No. 21.

Costs directly related to improvements of the land should be capitalized by the developer. They may include:

Land planning costs, including marketing and feasibility studies, direct salaries, legal and other professional fees, zoning costs, soil tests, architectural and engineering studies, appraisals, environmental studies, and other costs directly related to site preparation and the overall design and development of the project

On-site and off-site improvements, including demolition costs, streets, traffic controls, sidewalks, street lighting, sewer and water facilities, utilities, parking lots, landscaping, and related costs such as permits and inspection fees

Construction costs, including onsite material and labor, direct supervision, engineering and architectural fees, permits, and inspection fees

Project overhead and supervision, such as field office costs

Recreation facilities, such as golf courses, clubhouse, swimming pools, and tennis courts

Sales center and models, including furnishings

General and administrative costs not directly identified with the project should be accounted for as period costs and expensed as incurred.

Construction activity on a project may be suspended before a project is completed for reasons such as insufficient sales or rental demand. These conditions may indicate an impairment of the value of a project that is other than temporary, which suggests valuation issues (see Section 30.5).

In EITF Issue No. 90-8, "Capitalization of Costs to Treat Environmental Contamination," the EITF reached a consensus that, in general, costs incurred as a result of environmental contamination should be charged to expense. Such costs include costs to remove contamination, such as that caused by leakage from underground tanks; costs to acquire tangible property, such as air pollution control equipment; costs of environmental studies; and costs of fines levied under environmental laws. Nevertheless, those costs may be capitalized if recoverable but only if any one of the following criteria is met:

The costs extend the life, increase the capacity, or improve the safety or efficiency of property owned by the company, provided that the condition of the property after the costs are incurred must be improved as compared with the condition of the property when originally constructed or acquired, if later.

The costs mitigate or prevent environmental contamination that has yet to occur and that otherwise may result from future operations or activities. In addition, the costs improve the property compared with its condition when constructed or acquired, if later.

The costs are incurred in preparing for sale that property currently held for sale.

In EITF Issue No. 93-5, "Accounting for Environmental Liabilities," the EITF reached a consensus that an environmental liability should be evaluated independently from any potential claim for recovery (a two-event approach) and that the loss arising from the recognition of an environmental liability should be reduced only when it is probable that a claim for recovery will be realized.

The EITF also reached a consensus that discounting environmental liabilities for a specific clean-up site to reflect the time value of money is allowed, but not required, only if the aggregate amount of the obligation and the amount and timing of the cash payments for that site are fixed or reliably determinable.

The EITF discussed alternative rates to be used in discounting environmental liabilities but did not reach a consensus on the rate to be used. However, the Securities and Exchange CommissionSecurities and Exchange Commission (SEC) observer stated that SEC registrants should use a discount rate that will produce an amount at which the environmental liability theoretically could be settled in an arm's-length transaction with a third party. That discount rate should not exceed the interest rate on monetary assets that are essentially risk-free and have maturities comparable to that of the environmental liability. In addition, SEC Staff Accounting BulletinStaff Accounting Bulletin (SAB) 92 requires registrants to separately present the gross liability and related claim recovery in the balance sheet. SAB 92 also requires other accounting and disclosure requirements relating to product or environmental liabilities.

In October 1996, the AICPA issued SOP 96-1, "Environmental Remediation Liabilities." The SOP has three parts. Part I provides an overview of environmental laws and regulations. Part II provides authoritative guidance on the recognition, measurement, display, and disclosure of environmental liabilities. And part III (labeled as an appendix) provides guidance for auditors. A major objective of the SOP is to articulate a framework for the recognition, measurement, and disclosure of environmental liabilities. That framework is derived from SFAS No. 5, "Accounting for Contingencies."

The accounting guidance in the SOP is generally applicable when an entity is mandated to remediate a contaminated site by a governmental agency. However, the SOP does not address the following:

Accounting for pollution control costs with respect to current operations, which is addressed in EITF Issue No. 90-8, "Capitalization of Costs to Treat Environmental Contamination"

Accounting for costs with respect to asbestos removal, which is addressed in EITF Issue No. 89-13, "Accounting for the Costs of Asbestos Removal"

Accounting for costs of future site restoration or closure that are required upon the cessation of operations or sale of facilities, which is the subject of the FASB's project, "Obligations Associated with Disposal Activities"

Accounting for environmental remediation actions that are undertaken at the sole discretion of management and that are not undertaken by the threat of assertion of litigation, a claim, or an assessment

Recognizing liabilities of insurance companies for unpaid claims, which is addressed in SFAS No. 60, "Accounting and Reporting by Insurance Enterprises"

Asset impairment issues discussed in SFAS No. 144, "Accounting for the Impairment or Disposal of Long-Lived Assets," and EITF Issue No. 95-23, "The Treatment of Certain Site Restoration/Environmental Exit Costs When Testing a Long-Lived Asset for Impairment"

Prior to 1979, many developers capitalized interest costs as a necessary cost of the asset in the same way as bricks-and-mortar costs. Others followed an accounting policy of charging off interest cost as a period cost on the basis that it was solely a financing cost that varied directly with the capability of a company to finance development and construction through equity funds. This long-standing debate on capitalization of interest cost was resolved in October 1979 when the FASB published SFAS No. 34, "Capitalization of Interest Cost," which provides specific guidelines for accounting for interest costs.

SFAS No. 34 requires capitalization of interest cost as part of the historical cost of acquiring assets that need a period of time in which to bring them to that condition and location necessary for their intended use. The objectives of capitalizing interest are to obtain a measure of acquisition cost that more closely reflects the enterprise's total investment in the asset and to charge a cost that relates to the acquisition of a resource that will benefit future periods against the revenues of the periods benefited. Interest capitalization is not required if its effect is not material.

Assets qualifying for interest capitalization in conformity with SFAS No. 34 include real estate constructed for an enterprise's own use or real estate intended for sale or lease. Qualifying assets also include investments (equity, loans, and advances) accounted for by the equity method while the investee has activities in progress necessary to commence its planned principal operations, but only if the investee's activities include the use of such to acquire qualifying assets for its operations.

Capitalization is not permitted for assets in use or ready for their intended use, assets not undergoing the activities necessary to prepare them for use, assets that are not included in the consolidated balance sheet, or investments accounted for by the equity method after the planned principal operations of the investee begin. Thus land that is not undergoing activities necessary for development is not a qualifying asset for purposes of interest capitalization. If activities are undertaken for developing the land, the expenditures to acquire the land qualify for interest capitalization while those activities are in progress.

The capitalization period commences when:

Expenditures for the asset have been made.

Activities that are necessary to get the asset ready for its intended use are in progress.

Interest cost is being incurred.

Activities are to be construed in a broad sense and encompass more than just physical construction. All steps necessary to prepare an asset for its intended use are included. This broad interpretation includes administrative and technical activities during the preconstruction stage (such as developing plans or obtaining required permits).

Interest capitalization must end when the asset is substantially complete and ready for its intended use. A real estate project should be considered substantially complete and held available for occupancy upon completion of major construction activity, as distinguished from activities such as routine maintenance and cleanup. In some cases, such as in an office building, tenant improvements are a major construction activity and are frequently not completed until a lease contract is arranged. If such improvements are the responsibility of the developer, SFAS No. 67 indicates that the project is not considered substantially complete until the earlier of (1) completion of improvements or (2) one year from cessation of major construction activity without regard to tenant improvements. In other words, a one-year grace period has been provided to complete tenant improvements.

If substantially all activities related to acquisition of the asset are suspended, interest capitalization should stop until such activities are resumed. However, brief interruptions in activities, interruptions caused by external factors, and inherent delays in the development process do not necessarily require suspension of interest capitalization.