Lawrence F. Ranallo, CPA

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP

Keith R. Ugone, PhD

Analysis Group, Inc

INTRODUCTION[80]

Complex business disputes often require complex financial expert witness testimony. Depending on the nature of the case or the cause of action, financial expert witness testimony could cover a very broad range of accounting, financial, and economic topics. These topics might include historically based analyses, such as the insolvency date of a business or the past profitability of a business. Alternatively, the financial expert witness might testify regarding certain counterfactuals, such as the profitability of a business in the absence of an alleged wrongful act. Finally, a financial expert witness might even testify on economic causation issues, including the impact of market-related events (i.e., industry downturns or increased competition) on the profitability of a business.[81]

Hence, depending on the facts and circumstances of a business dispute, financial expert witnesses could have a number of interwoven important roles. The financial expert witness could provide the trier of fact with guidance as to the economic harm the plaintiff may have suffered. Alternatively, the financial expert witness could provide guidance as to the existence/nonexistence of a financial causal linkage between the alleged wrongful conduct and the claimed economic harm.[82] A certified public accountant (CPA), a financial analyst, an economist, or a statistician, depending on the facts and circumstances of the dispute, could be equally well qualified to render these types of opinions.

The requirements for expert witness qualification in federal cases are provided in certain federal rules, and, since 1993, in the Daubert case and its case progeny.[83] The requirements for expert witness qualification in state cases vary by jurisdiction; some states follow the Daubert criteria while other states apply requirements similar to the older Frye criteria.[84]

Rule 702 of the Federal Rules of Evidence provides for the admissibility of expert testimony as follows:

If scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will assist the trier of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue, a witness qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education, may testify thereto in the form of an opinion or otherwise, if (1) the testimony is based upon sufficient facts or data, (2) the testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods, and (3) the witness has applied the principles and methods reliably to the facts of the case.[85]

In its Daubert opinion, the Supreme Court established four now commonly cited nonexclusive criteria for the admissibility of scientific and technical expert testimony. These criteria were developed to assist the trial judge to "make a preliminary assessment of whether the testimony's underlying reasoning or methodology is scientifically valid and properly can be applied to the facts at issue."[86] The criteria are:

Whether the theory or technique in question can be (and has been) tested

Whether the theory or technique has been subjected to peer review and publication

Whether the theory or technique has a known or potential error rate and the existence and maintenance of standards concerning its operation

Whether the theory or technique has attracted widespread acceptance within a relevant scientific community

The Kumho Tire case in 1999 clarified that the nonexclusive "Daubert criteria" were also applicable to financial experts such as CPAs, financial analysts, economists, and statisticians, among others, in federal cases.

Consequently, financial expert witnesses must be aware of the criteria being used to judge the admissibility of their work and opinions. Since Kumho Tire, there has been a particular focus on how courts have applied the "Daubert criteria" to financial experts—especially since financial experts are often used in the liability aspects of cases involving accounting and auditing issues and are used for damage quantification and related economic causation issues.

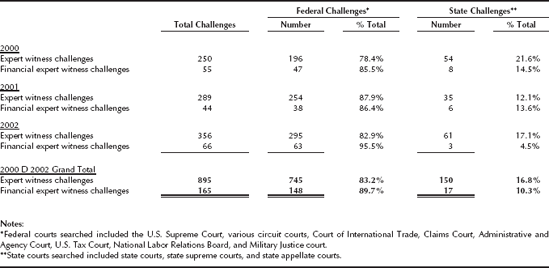

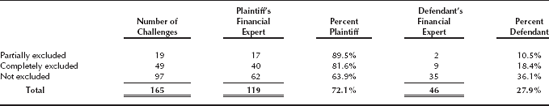

In this chapter we present our findings from an analysis of published opinions of federal and state cases relating to challenges and exclusions of financial expert witnesses over the 2000–2002 time period (i.e., post-Kumho Tire). It is important to note that our search criteria included published opinions that referenced the Kumho Tire case decision explicitly—which we used as a primary indicator of matters likely to involve challenges to nonscientific experts such as CPAs, financial analysts, economists, and statisticians. (See Exhibit 47.1.)[87] Our sample included 895 challenges identified through published opinions meeting these criteria.[88] Financial experts were named in 165 of these 895 challenges, with 68 financial experts being excluded either in whole or in part.[89]

Several interesting conclusions can be drawn from the opinions reviewed, including the fol-lowing:

The number of challenges to experts of all types is increasing. In 2000, there were 250 challenges to expert witnesses in general.[90] This number increased to 289 in 2001 and 356 in 2002. This trend is to be expected. The exclusion of a litigant's expert is often devastating to that party's case. Hence, challenging the admissibility of an expert's opinion is an increasingly utilized weapon in the arsenal of opposing counsel.

Once challenged, the rate at which financial experts are excluded in whole or in part is decreasing. Based on our sample of cases, 22.0 percent of the challenges in 2000 involved financial expert witnesses. The corresponding figures in 2001 and 2002 were 15.2 percent and 18.5 percent, respectively. Hence, the relative proportion of challenges between financial and nonfinancial expert witnesses has not appreciably changed between 2000 and 2002.[91] Interestingly, however, the percentage of financial experts excluded in whole or in part (once challenged) over this same time period declined from 54.5 percent to 40.9 percent to 30.3 percent. While at first this result may appear paradoxical, we believe it is the natural result of the increased emphasis on challenging the admissibility of the opposing financial expert's opinions. Two forces are creating this result. To the extent a Daubert challenge is a strategy increasingly utilized by opposing counsel, the quality of challenges and the likelihood of exclusion may not be as high at the margin when increasing numbers of challenges are made.[92] In addition, to the extent it is likely a financial expert has to withstand both a Daubert challenge and cross-examination, financial experts are more inclined (at the margin) to perform higher-quality investigations, to use generally accepted methodologies, and to use methodologies that fit the facts and circumstances of the particular matter. In other words, financial experts have appropriately responded to the incentives created by the likelihood of a Daubert challenge. Diminishing returns to financial expert witness challenges and financial expert witness response to the Daubert environment have caused the percentage of financial experts excluded in whole or in part to decline.

Plaintiff side financial experts are challenged and excluded more frequently than defense side financial experts. Based on our sample of cases, plaintiff financial experts are two to three times as likely to be challenged relative to defense financial experts. In 2000, 76.4 percent of financial expert challenges involved plaintiffs' financial experts. The corresponding figures in 2001 and 2002 were 68.2 percent and 71.2 percent, respectively. These trends carry over to actual exclusions as well. In 2000, 79.3 percent of financial expert exclusions were plaintiff financial experts. This number increased to 83.3 percent in 2001 and 90.0 percent in 2002. Again, in many respects, these results are not surprising. First, a defendant can survive without its financial expert witness better than a plaintiff can survive without its financial expert witness. (The plaintiff needs a financial expert to put forth a claimed damages figure, whereas a defendant could always just cross-examine the plaintiff's financial expert without putting its own expert on the witness stand.) Hence, at the margin, there is a greater incentive to challenge the plaintiff's financial expert than the defendant's financial expert. In addition, the plaintiff's financial expert often is building or constructing a damage model, while the defendant's financial expert is often just evaluating the work of the plaintiff's financial expert. In terms of pure numbers, the plaintiff's financial expert has many more assumptions and inputs to justify relative to defendant's financial expert, leading to a greater likelihood of a challenge. For the same reason, there is a greater likelihood the plaintiff's financial expert will ultimately be excluded in whole or in part.

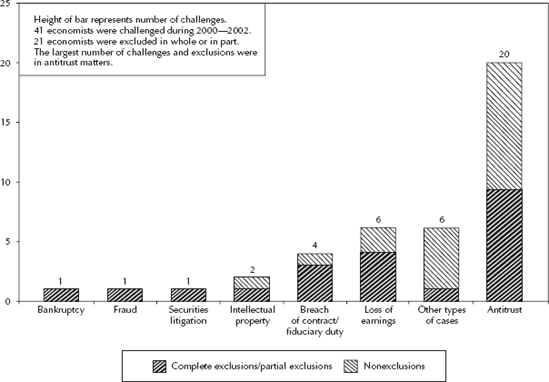

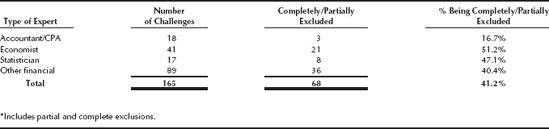

The rate of challenges to accountants/CPAs as testifying experts appears to be lower than that for other types of financial experts. The success rate of excluding accountants/CPAs is lower as well.[93] Of the 165 challenges to financial experts, 18 related to accountants/CPAs, 41 related to economists, and 17 related to statisticians.[94] Only three of the accountants/CPAs were excluded in whole or in part, while 21 of the economists and eight of the statisticians were excluded in whole or in part. Care should be exercised when interpreting these figures, however. These figures should not be interpreted as meaning a financial expert with a CPA is necessarily less susceptible to challenges and exclusions relative to financial experts with a PhD in economics (for example). To the contrary, these figures are likely the product of (a) the nature of the engagements traditionally assigned to different types of financial experts, (b) the data that may be available to properly conduct the required analysis in the engagements traditionally assigned to different types of financial experts, and (c) the degree to which the required testimony deviates from the interpretation of historical data toward projecting business performance under an alternative set of conditions. CPAs, in certain types of engagements, may be assessing accounting rules, using accounting rules to support their opinions, or opining on issues relating to the actual past performance of a business. In contrast, the majority of the challenges and exclusions relating to economists pertained to antitrust cases. (See Exhibit 47.2.) Defining a relevant market and/or hypothesizing as to prices, output, market shares, and profits in the absence of an alleged monopolization may place the economist at greater risk of challenge and possible exclusion than an accountant/CPA functioning as a financial expert in matters that do not involve these components. Hence, we believe it is the nature of the cases and the required analyses that explain the different exclusion rates of CPAs and economists rather than alternative explanations.[95]

Other details to our study are presented in the remainder of this chapter, followed by additional conclusion.

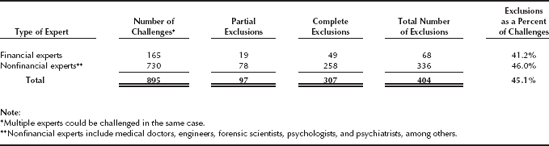

Reported in Exhibit 47.3 is the number of challenges relating to the admissibility of financial and nonfinancial expert witnesses over the January 2000 through December 2002 time period. The results of these challenges are also reported in Exhibit 47.2 Our investigation indicates that:

Of the 895 challenges identified using our search criteria, financial experts were challenged a total of 165 times (18.4 percent) while 730 challenges (81.6 percent) involved nonfinancial experts.

When financial experts were challenged, their testimony was excluded in whole or in part in 68 cases or 41.2 percent of the time.[96] In contrast, nonfinancial experts were excluded in whole or in part in 336 cases or 46.0 percent of the time.[97]

Financial and nonfinancial experts have their testimony excluded entirely at a higher rate than excluded in part. Our investigation reveals 72.1 percent of the financial expert exclusions and 76.8 percent of the nonfinancial expert exclusions were in whole rather than in part.

Based on the above data, once challenged, financial and nonfinancial experts appear to be excluded in roughly the same proportions.

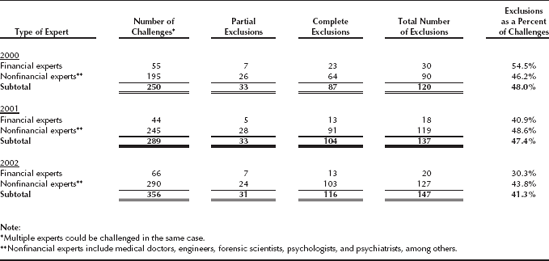

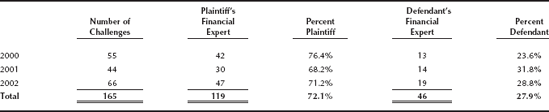

The annual number of challenges and rate of exclusions of financial and nonfinancial expert witnesses over the 2000–2002 time period is presented in Exhibit 47.4. Based on annual data:

The number of challenges of experts has trended upward. The total number of expert challenges increased by 15.6 percent in 2001 (from 250 in 2000 to 289 in 2001) and increased by 23.2 percent in 2002 (from 289 in 2001 to 356 in 2002).

Financial expert challenges have stayed relatively steady as a percentage of the total number of challenges over this three-year period. In 2000, 55 of the 250 challenges (22.0 percent) were challenges of financial experts. In 2002, 66 of the 356 challenges (18.5 percent) were challenges of financial experts.

The rate at which financial experts have been excluded, once challenged, has declined from 54.5 percent in 2000 to 40.9 percent in 2001 to 30.3 percent in 2002.[98] As discussed previously, this is likely the result of two forces. At the margin, with increases in the number of challenges, the likelihood of a successful challenge to a financial expert witness may be less. Also, at the margin, the quality of work prepared by financial expert witnesses may have improved in response to increased scrutiny stemming from tightened admissibility guidelines. Both of these forces likely explain the decline in the exclusion rate over the 2000–2002 time period.[99]

Interestingly, based on the data in Exhibit 47.4, it appears as though a crossover has occurred with respect to the rate of exclusions of financial and nonfinancial expert witnesses once challenged. Whereas in 2000, when challenged, financial experts were excluded at a higher rate than nonfinancial experts, by 2002 nonfinancial experts were excluded at a higher rate.[100] In 2000, 54.5 percent of the challenges of financial experts resulted in a partial or complete exclusion, declining to 30.3 percent in 2002. In contrast, 46.2 percent of the challenges of nonfinancial experts resulted in a partial or complete exclusion in 2000, declining only slightly to 43.8 percent in 2002.

We next determined the reasons financial experts were excluded or partially excluded.[101] This analysis was done in the context of the Rule 702 focus on the qualifications of the proposed expert as well as the relevance and reliability of the planned testimony. When financial experts are excluded, it is more likely to be as a result of the lack of reliability in the planned testimony than as a result of relevance issues or the qualifications of the expert. While multiple reasons were often given for the exclusions of the financial experts studied, reliability was mentioned in over 80 percent of the exclusions, relevance was mentioned in half of the exclusions, and qualifications were mentioned in a quarter of the exclusions. Finally, when financial expert testimony is determined to be unreliable, it is more likely to be a result of problems with the quantity or validity of the data used by the expert than with any of the Daubert criteria.

Reported in Exhibits Exhibit 47.5, 47.6, and 47.7 is an analysis of challenges and exclusions by the party engaging the financial expert. Our analysis of the data shows:

Of the 165 financial expert challenges identified, 119 (or 72.1 percent) were engaged by the plaintiff. (See Exhibit 47.5.) Thus, it is more likely that a financial expert will be challenged when engaged by the plaintiff than the defendant.

The number of challenges of plaintiff financial experts relative to defense financial experts has remained consistent in each year. (See Exhibit 47.6.) At least two out of every three challenges to financial experts are plaintiff side in each year.

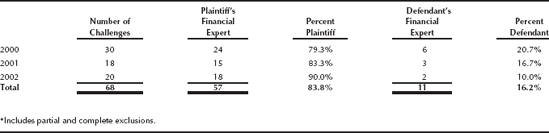

Once challenged, plaintiff financial experts are more likely to be excluded in whole or in part than defense financial experts. (See Exhibit 47.7.) Although 72.1 percent of the challenges are plaintiff side, 83.8 percent of the exclusions or partial exclusions are plaintiff side. In contrast, while 27.9 percent of the challenges are defense side, only 16.2 percent of the exclusions in whole or in part are defense side.

Notably, while the rate at which financial experts are excluded is declining (as previously discussed), such observations are not quite descriptive of the rate at which plaintiff financial experts are excluded (once challenged) relative to defendant financial experts.

The data reported in Exhibit 47.6 suggests plaintiff financial experts are consistently challenged at a rate two to three times that of defendant financial experts. Annually, over the 2000–2002 time period, 68.2 percent to 76.4 percent of the challenges to financial experts were to the plaintiff's financial expert. The data reported in Exhibit 47.7 suggests plaintiff financial experts are consistently excluded at a rate four to nine times that of defendant financial experts. Annually, over the 2000–2002 time period, 79.3 percent to 90.0 percent of the exclusions of financial experts were to the plaintiff's financial expert.

Exhibits 47.6 and 47.7 combined demonstrate that plaintiff and defendant financial experts have experienced declines in the proportion of exclusions, once challenged. However, the percentage of plaintiff financial experts excluded in whole or in part has not declined to the same extent as defense financial expert exclusions. In 2000, 24 exclusions occurred relating to the 42 plaintiff financial expert challenges (57.1 percent). In 2002, 18 exclusions occurred relating to the 47 plaintiff financial expert challenges (38.3 percent). In comparison, in 2000, 6 of 13 challenged defendant financial experts were excluded (46.2 percent). This figure was reduced to 2 of 19 challenged defendant financial experts being excluded in 2002 (10.5 percent).

Next we looked at the composition of financial expert challenges and exclusions in the context of the particular financial expertise involved. While the pool of financial experts identified in cases is diverse,[102] we have separately analyzed the challenges and exclusions of economists, statisticians, and accountants/CPAs. This data is reported in Exhibit 47.8. Note that because our analysis is focused only on those cases in which a challenge was made in federal and state cases referring to Kumho Tire, it is not possible to calibrate the rate of a particular expert exclusion to the many other cases in which a financial expert is not challenged and provides testimony. However, we have found:

Among financial experts, accountants/CPAs appear to be among the least frequently challenged financial experts.

Among financial experts, accountants/CPAs appear to have the lowest proportion of exclusions. Out of 68 financial expert exclusions in whole or in part, only three CPAs have been excluded. In contrast, each of the other categories of financial experts—economists, statisticians, and other financial experts—has a higher percentage of exclusions when challenged than accountants/CPAs.

However, as previously discussed, care must be exercised when interpreting these figures. The empirical data presented does not support the proposition that when two functionally different but equally qualified experts are being considered for retention, and the nature of the assignment is such that the talents of either type of expert are appropriate, the CPA will have a lower probability of being challenged or excluded.

Figure 47.8. Financial Expert Challenges and Exclusions* by Expert Type; January 2000–December 2002.

To the contrary, the figures reported above are likely the product of (a) the nature of the engagements traditionally assigned to different types of financial experts, (b) the data that may be available to properly conduct the required analysis in the engagements traditionally assigned to different types of financial experts, and (c) the degree to which the required testimony deviates from the interpretation of historical data toward projecting business performance under an alternative set of conditions. Hence, we believe it is frequently the nature of the cases and the required analyses that explain the different exclusion rates of CPAs and economists rather than alternative explanations.

The trends identified over the three-year survey period largely continued in the six-month period ended June 30, 2003, with some important exceptions. Reported below are notable results in the first six months of 2003.

Financial expert testimony was wholly or partially excluded in 24 situations (or 55.8 percent of the financial expert challenges). The exclusion rate in the first six months of 2003 was greater than the exclusion rate for the year 2002.

For these financial expert exclusions, there are a higher number of partial exclusions (17 cases) than complete exclusions (7 cases). This is a reversal of prior trends.

The reliability of the financial expert's opinion (based on the underlying facts and data considered and the methodology used to formulate an opinion) was again the predominant reason for exclusion. Deficiencies relating to the reliability of the proposed testimony were cited in nearly 80 percent of the 24 exclusions. The qualifications of the financial expert were cited in only one exclusion.

Of 43 total challenges, 30 (or 69.8 percent) were directed to plaintiff financial experts. Of these 30 challenges, plaintiff financial experts were excluded 63.3 percent of the time. This is in contrast to defense financial experts, who were excluded in 38.5 percent of the challenges reviewed.

Accountants/CPAs did not fare as well in the first six months of 2003. Whereas only 4 of the 43 financial expert challenges related to accountants or CPAs, all 4 of such experts were wholly or partially excluded, more than the total number of exclusions for this type of expert in all of the prior three years surveyed.[103]

In summary, certain observations and trends stand out in the analysis of federal and state cases over the past three years where the admissibility of the financial expert witness's opinions has been challenged:

The number of challenges to experts of all types is increasing.

Once challenged, the rate at which financial experts are excluded in whole or in part decreased over the 2000–2002 time period.

Plaintiff financial experts are challenged and excluded more frequently than defense financial experts.

The rate of challenges to accountants/CPAs as testifying experts appears to be lower than that for other types of financial experts. The success rate of excluding accountants/CPAs is lower as well.[104]

As discussed, we believe it is the nature of the cases and the required analyses that explain the different exclusion rates of CPAs and other financial experts rather than alternative explanations. However, it is worth mentioning, admittedly with a mix of both fact and intuition, that because the CPA designation is well established and well known, it may be qualifying in certain types of litigation roles and cases. While the designation is not a sine qua non for the admissibility of testimony, the accreditation of a CPA—which embodies completion of defined education, examination, experience, and annual continuing education requirements—is an established basis for qualification of the financial expert in a suitable litigation context.[105]

CPAs are often chosen for certain defined types of roles in a litigation context that are customarily and commonly within the province of CPAs. For example, the historical cost focus of accountants/CPAs is conducive to the evaluation of historical accounting data in a litigation context. This may be a factor explaining the lower rate of challenges and exclusions of CPAs relative to non-CPAs who conduct analyses outside of traditional historical accounting analyses.

Finally, CPAs may benefit from the professional standards to which they must adhere when faced with a Daubert challenge. Since the Daubert criteria include peer review and general acceptance of a methodology, the CPA can turn to the codified professional standards of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) and other standard-setting organizations, among other information, as a basis on which professional opinions may be drawn. Such accounting standards have heretofore been the result of an established process that largely includes focused research, public input, exposure of issues and standards for open comment, and expert deliberative decision making by members of panels and boards.

In a litigation context, the CPA is able to rely not only on generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), but also on the standards defined by the AICPA related to audit, consulting (including litigation or business valuation services) or attestation engagements to perform the analysis needed to support opinions relating to liability or economic damages. In contrast, other types of financial experts, though highly skilled and trained, do not have a set of technical standards as codified as those of CPAs. Of course, as a cautionary note, the protections these standards provide the CPA are only applicable to CPAs who are retained on matters where these standards play a role or are relevant to the nature of the inquiry being made. To the extent statistical, economic, or econometric analyses are required, the standards on which a CPA often relies may not be as directly relevant.

[80] 1We wish to thank Sharon Freeman, Na Dawson, and Aijun Besio for research assistance. The information contained in this chapter does not represent the views of either Pricewaterhouse-Coopers, LLP, or Analysis Group, Inc.

[81] 2This list is illustrative only and is not intended to be all-inclusive. It is quite common for financial experts to testify on these or similar subjects in securities-related matters, antitrust matters, intellectual property matters, breach of contract disputes, purchase price disputes, and loss of earnings matters, among others.

[82] 3Here we make a distinction between economic or financial causation versus legal causation (e.g., whether a wrongful act occurred).

[83] 4See, for example, William Daubert, et ux., etc., et al. v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (92–102), 509 U.S. 579 (1993) and Kumho Tire Company, LTD., et al. v. Patrick Carmichael, etc., et al. (97–1709), 526 U.S. 137 (1999).

[84] 5See Frye v. United States, 292 F. 1013 (1923). See also, for example, the Supreme Court of Texas case captioned E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, Inc. v. C. R. Robinson and Shirley Robinson (94–0843), 923S.W.2d 549 (1995).

[85] 6Rule 702, Federal Rules of Evidence (Including Amendments Effective December 1, 2000), 2000–2001 Edition, p. 113. As implied by Rule 702, the expert witness must use a reliable methodology and a methodology that fits the facts and circumstances of the case.

[86] 7Daubert, 113 Supreme Court Reporter, 509 U.S. 579, p. 2790.

[87] 8Although broader search criteria would identify additional cases in federal and state jurisdictions, the expert challenges identified using the stated search criteria provided interesting and meaningful insights into certain trends regarding challenges to financial expert witness testimony since Kumho Tire.

[88] 9We conducted research on cases citing Kumho Tire (526 U.S. 137) in the Lexis Nexis federal and state court cases database.

[89] 10Some identified published opinions addressed the proposed testimony of more than one expert.

[90] 11Using the Kumho Tire search criteria previously described.

[91] 12The purpose of this chapter is to identify and discuss certain observations and trends relating to expert witness challenges and exclusions. We have not analyzed whether statistically significant differences exist between certain percentages we report.

[92] 13Restated, in the aggregate, it is likely there are diminishing returns to Daubert challenges.

[93] 14While some courts identified the expert in question as a CPA, others simply identified the expert as an accountant. Consequently, the statistics reported in this article may include both CPAs and non-CPA accountants.

[94] 15The remaining financial experts were classified as "other financial experts" in our analysis. In some challenges, not enough information was reported to identify these "other financial experts" as CPAs, economists, or statisticians. In other challenges, "other financial experts" included financial analysts and appraisers, among others.

[95] 16It is interesting to note the reasons given for the exclusion of the three accountants/CPAs discussed in the text. In re: Bonham (2000 Bankr. Lexis 727), a bankruptcy court judge excluded the CPA "based on substantial factual mistakes, speculation, innuendo, and inferences which are not supported by full explanations and analysis." In United States v. Sparks (2001 U.S. App. Lexis 8002), the circuit court judge upheld the exclusion of an accountant "because there was no indication of authenticity [of documents relied on], however, [the accountant's] testimony, which was based on those documents, did not 'rest on a reliable foundation' and had to be excluded under Rule 702. Daubert, 509 U.S. at 597." In United States v. Rockwell Space Operations (2002 U.S. Dist. Lexis 6650), the district court judge wrote, "As a consequence, the accuracy of [the CPA's] damage assessment is entirely dependent upon the accuracy and the credibility of [the plaintiff's] non-expert and unreliable estimates. [The CPA's] opinion is not reliable because it was built upon a faulty foundation: the uncorroborated and unreliable estimates of [the plaintiff]." [Bracketed terms have been added for clarity.]

[96] 17Financial experts were excluded in whole 49 times and excluded in part 19 times.

[97] 18Nonfinancial experts were excluded in whole 258 times and excluded in part 78 times.

[98] 19The rate at which nonfinancial experts have been excluded, once challenged, increased slightly in 2001 and then declined in 2002. However, the rate at which nonfinancial experts have been excluded did not decline to the same extent in 2002 as compared to the figures for financial experts.

[99] 20Analysis of future exclusions will provide insights as to whether the exclusion rate has reached its steady state or equilibrium level. While not part of this study, the case filings mix could also impact the exclusion rate of financial experts over time.

[100] 21In whole or in part.

[101] 22Based on a reading of the published opinions reviewed, reasons for the exclusion of financial experts were categorized as relating to relevance issues, reliability issues, and/or qualification issues. A particular expert may have been excluded for more than one reason.

[102] 23Financial experts in this context refer to economists, statisticians, accountants/CPAs, appraisers, finance professors, and so on.

[103] 24The reasons for these four exclusions are as follows. In re: EZ Dock, Inc. v. Schafer Sys (2003 U.S. Dist. Lexis 3634), the circuit court judge determined that "In his expert report, therefore, [the CPA] has not himself formed an opinion as to the existence of a 'two supplier' market; he has simply adopted Wortley's opinion regarding the nature of the market .... His proposed opinions regarding the existence of a demand for the patented product and the absence of non-infringing alternative products is 'not based upon sufficient facts or data' as required by Rule 702." In re: Valentino v. Proviso Twp. (2003 U.S. Dist. Lexis 11574), the circuit judge found that "[The CPA] stated he thought this analysis was widespread knowledge; however, neither [plaintiff's] response to the motion nor [the CPA's] subsequent affidavit makes mention of anything to support his assertion that his borrowing history analysis is widespread knowledge or a reliable method to determine the borrowing ability of a Township." In re: Space Maker Designs, Inc. v. Weldon F. Stump and Company, Inc. (2003 U.S. Dist. Lexis 3941), the district judge found that "Expert reports should be 'detailed and complete' so as 'to avoid the disclosure of 'sketchy and vague' expert information." Sierra Club at 571 .... Under the terms of the Agreed Amended Scheduling Order, Defendants were required to file a complete statement of all opinions to be expressed and the basis and reasons therefore. [The CPA's] expert report falls short of that standard." As to the CPA's licenses, the court found that "None of those licenses make him qualified to opine on economic trends and their likely effect on profits." In re: JRL Enterprises, Inc. v. Procorp Associates, Inc. (2003 U.S. Dist. Lexis 9397) the district court found that the expert's calculations were based solely on projections found in the agreement. The district court noted that the expert performed no market analysis to verify the reasonableness or accuracy of the projections in the DA Agreement. 1998 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 15414 at *1. The court found that this failure established that the expert's calculations could not be evaluated for accuracy. Furthermore, the court found that the expert had failed to establish that the expert's numbers had any basis in reality. The court found that "the expert had failed to offer any evidence of general acceptance, or known rate of error for his methods; finally, the court said that the plaintiff had shown no evidence that the expert's calculations were anything more than an exercise in arithmetic based on inherently unreliable values. 1998 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 15414 at *4." [Bracketed terms have been added for clarity.] Footnote citations have been removed.

[104] 25Subject to the caveats discussed in this article.

[105] 26This is not true in all types of litigation contexts. For example, a CPA designation would not provide a shield to a Daubert challenge if a CPA was attempting to opine on relevant market issues in an antitrust case.