Benjamin A. McKnight III, CPA

Arthur Andersen LLP, Retired

Many types of business have their rates for providing services set by the government or other regulatory bodies, for example, utilities, insurance companies, transportation companies, hospitals, and shippers. The enterprises addressed in this chapter are limited to electric, gas, telephone, and water (and sewer) utilities that are primarily regulated on an individual cost-of-service basis. Effective business and financial involvement with the utility industry requires an understanding of what a utility is, the regulatory compact under which utilities operate, and the interrelationship between the rate decisions of regulators and the resultant accounting effects.

Regulated utilities are similar to other businesses in that there is a need for capital and, for private sector utilities, a demand for investor profit. Utilities are different in that they are dedicated to public use—they are obligated to furnish customers service on demand—and the services are considered to be necessities. Many utilities operate under monopolistic conditions. A regulator sets their prices and grants an exclusive service area, which probably serves a relatively large number of customers. Consequently, a high level of public interest typically exists regarding the utility's rates and quality of service.

Only a utility that has a monopoly of supply of service can operate at maximum economy and, therefore, provide service at the lowest cost. Duplicate plant facilities would result in higher costs. This is particularly true because of the capital-intensive nature of utility operations, that is, a large capital investment is required for each dollar of revenue.

Because there is an absence of free market competitive forces such as those found in most business enterprises, regulation is a substitute for these missing competitive forces. The goal of regulation is to provide a balance between investor and consumer interests by substituting regulatory principles for competition. This means regulation is to:

Provide consumers with adequate service at the lowest price

Provide the utility the opportunity, not a guarantee, to earn an adequate return so that it can attract new capital for development and expansion of plant to meet customer demand

Prevent unreasonable prices and excessive earnings

Prevent unjust discrimination among customers, commodities, and locations

Insure public safety

To meet the goals of regulation, regulated activities of utilities typically include these six:

Service area

Rates

Accounting and reporting

Issuance of debt and equity securities

Construction, sale, lease, purchase, and exchange of operating facilities

Standards of service and operation

This chapter covers the historical development of regulated utilities as a monopoly service provider and the regulation of their rates as a substitute for competition. Although many of the historical practices continue, regulated utilities are increasingly operating in a deregulated, competitive environment. Certain industry segments have been more affected than others by the judicial, legislative, and regulatory actions, as well as technological changes, that have produced this shift. These industry segments include long distance telecommunications services, natural gas production and transmission, and electric generation.

Some knowledge of the history of regulation is essential to understanding utilities. Companies that are now regulated utilities find themselves in that position because of a long sequence of political events, legislative acts, and judicial interpretations.

Rate regulation of privately owned business was not an accepted practice during the early history of the United States. This concept has evolved because important legal precedents have established not only the right of government to regulate but also the process that government bodies must follow to set fair rates for services. The background and the facts of Munn v. Illinois [94 U.S. 113 (1877)] are significant and basic to the development of rate making since the case established a U.S. legal precedent for the right of government to regulate and set rates in cases of public interest and necessity.

In 1871, the Illinois State Legislature passed a law that prescribed the maximum rates for grain storage and that required licensing and bonding to ensure performance of the duties of a public warehouse. The law reflected the popular sentiment of midwestern farmers at that time against what they felt was a pricing monopoly by railroads and elevators. Munn and his partner, Scott, owned a grain warehouse in Chicago. They filed a suit maintaining that they operated a private business and that the law deprived them of their property without due process.

The case ultimately reached the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court decided that, when private property becomes "clothed with a public interest," the owner of the property has, in effect, granted the public an interest in that use and "must submit to be controlled by the public for the common good." The Court was impressed by Munn and Scott's monopolistic position while furnishing a service practically indispensable to the public.

From the precedent of Munn, railroads, a water company, a grist mill, stockyards, and finally gas, electric, and phone companies were brought under public regulation. Thus, when utilities finally came into existence in the 20th century, the framework for regulation already was in place and did not have to be decided by the courts. When state legislatures began to set up utility commissions, it was the Munn decision that established beyond question their right to do so.

A second important case that began to establish the principle of "due process" in rate making is Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad Co. v. Minnesota ex rel. Railroad & Warehouse Comm. [134 U.S. 418 (1890)]. In this case, the courts first began to address the issue of standards of reasonableness in regulation. The U.S. Supreme Court decided that a Minnesota law was unconstitutional because it established rate regulation but did not permit a judicial review to test the reasonableness of the rates. The Court found that the state law violated the due process provisions of the 14th Amendment because the utility was deprived of the power to charge reasonable rates for the use of its property, and if the utility was denied judicial review, then the company would be deprived of the lawful use of its property and, ultimately, the property itself.

A third important case, Smyth v. Ames [169 U.S. 466 (1898)], established the precedent for the concept of "fair return upon the fair value of property." During the 1880s, the state of Nebraska passed a law that reduced the maximum freight rates that railroads could charge. The railroads' stockholders brought a successful suit that prevented the application of the lowered rates. The state appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, which unanimously ruled that the rates were unconstitutionally low by any standard of reasonableness.

In its case, the state maintained that the adequacy of the rates should be tested by reference to the present value, or reproduction cost, of the assets. This position was attractive to the state because the current price level had been declining. The railroad was built during the Civil War, a period that was marked by a high price level and substantial inflation, and the railroad believed that its past costs merited recognition in a "test of reasonableness."

In reaching its decision, the Court began the formulation of the "fair value" doctrine, which prescribed a test of the reasonableness and constitutionality of regulated rates. The Supreme Court's opinion held that a privately owned business was entitled to rates that would cover reasonable operating expenses plus a fair return on the fair value of the property used for the convenience of the public.

The Smyth v. Ames decision also established several rate-making terms still in use today. This was the first attempt by the courts to define rate-making principles. These four terms include:

Original Cost of Construction. The cost to acquire utility property.

Fair Return. The amount that should be earned on the investment in utility property.

Fair Value. The amount on which the return should be based.

Operating Expenses. The cost to deliver utility services to the public.

Each of these three landmark cases, especially Smyth v. Ames, established the inability of the legislative branch to effectively establish equitable rates. They also demonstrated that the use of the judicial branch is an inefficient means of accomplishing the same goal. In Smyth v. Ames, the U.S. Supreme Court, in essence, declared that the process could be more easily accomplished by a commission composed of persons with special skills and experience and the qualifications to resolve questions concerning utility regulation.

A view of the overlays of regulatory commissions will be helpful in understanding their unique position and responsibilities.

The interstate activities of public utilities are under the jurisdiction of several federal regulatory commissions. The members of all federal regulatory commissions are appointed by the executive branch and are confirmed by the legislative branch. The judicial branch can review and rule on decisions of each commission. This form of organization represents a blending of the functions of the three separate branches of government.

The Federal Communications CommissionFederal Communications Commission (FCC), established in 1934 with the passage of the Communications Act, succeeded the Federal Radio Commission of 1927. At that time the FCC assumed regulation of interstate and foreign telephone and telegraph service from the Interstate Commerce Commission, which was the first federal regulatory commission (created in 1887). The FCC prescribes for communications companies a uniform system of accountsUniform System of Accounts (USOA) and depreciation rates. It also states the principles and standard procedures used to separate property costs, revenues, expenses, taxes, and reserves between those applicable to interstate services under the jurisdiction of the FCC and those applicable to services under the jurisdiction of various state regulatory authorities. In addition, the FCC regulates the rate of return carriers may earn on their interstate business.

The Federal Energy Regulatory CommissionFederal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) was created as an agency of the cabinet-level Department of Energy in 1977. The FERC assumed many of the functions of the former Federal Power CommissionFederal Power Commission (FPC), which was established in 1920. The FERC has jurisdiction over the transmission and sale at wholesale of electric energy in interstate commerce. The FERC also regulates the transmission and sale for resale of natural gas in interstate commerce and establishes rates and prescribes conditions of service for all utilities subject to its jurisdiction. The entities must follow the FERC's USOA and file a Form 1 (electric) or Form 2 (gas) annual report.

The Securities and Exchange Commission was established in 1934 to administer the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. The powers of the SEC are restricted to security transactions and financial disclosures—not operating standards. The SEC also administered the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 (the 1935 Act), which was passed because of financial and services abuses in the 1920s and the stock market crash and subsequent depression of 1929–1935. Under the 1935 Act, the SEC was given powers to regulate the accounting, financing, reporting, acquisitions, allocation of consolidated income taxes, and parent–subsidiary relationships of electric and gas utility holding companies. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 includes the repeal of the 1935 Act, which is effective on February 8, 2006, and will eliminate significant federal restrictions on the scope, structure, and ownership of electric companies. However, the repeal is accompanied by the transfer of certain authority to the FERC and state regulatory commissions.

All 50 states and the District of Columbia have established agencies to regulate rates. State commissioners are either appointed or elected, usually for a specified term. Although the degree of authority differs, they have authority over utility operations in intrastate commerce. Each state commission sets rate-making policies in accordance with its own state statutes and precedents. In addition, each state establishes its prescribed forms of reporting and systems of accounts for utilities. However, most systems are modifications of the federal USOAs.

The process for establishing rates probably constitutes the most significant difference between utilities and enterprises in general. Unlike an enterprise in general, where market forces and competition establish the price a company can charge for its products or services, rates for utilities are generally determined by a regulatory commission. The process of establishing rates is described as rate making. The administrative proceeding to establish utility rates is typically referred to as a rate case or rate proceeding. Utility rates, once established, generally will not change without another rate case.

The establishment of a rate for a utility on an individual cost-of-service basis typically involves two steps. The first step is to determine a utility's general level of rates that will cover operating costs and provide an opportunity to earn a reasonable rate of return on the property dedicated to providing utility services. This process establishes the utility's required revenue (often referred to as the revenue requirement or cost-of-service). The second step is to design specific rates in order to eliminate discrimination and unfairness from affected classes of customers. The aggregate of the prices paid by all customers for all services provided should produce revenues equivalent to the revenue requirement.

This first step of rate regulation, on an individual cost-of-service basis, is the determination of a utility's total revenue requirement, which can be expressed as a rate-making formula, which involves five areas:

Rate Base × Rate of Return = Return(Operating Income)

Return + Operating Expenses = Required Revenue(Cost of Service)

Rate Base. The amount of investment in utility plant devoted to the rendering of utility service upon which a fair rate of return may be earned.

Rate of Return. The rate determined by the regulatory agency to be applied to the rate base to provide a fair return to investors. It is usually a composite rate that reflects the carrying costs of debt, dividends on preferred stock, and a return provision on common equity.

Return. The rate base multiplied by rate of return.

Operating Expenses. Merely the costs of operations and maintenance associated with rendering utility service. Operating expenses include:

Depreciation and amortization expenses

Production fuel and gas for resale

Operations expenses

Maintenance expenses

Income taxes

Taxes other than income taxes

Required Revenue. The total amount that must be collected from customers in rates. The new rate structure should be designed to generate this amount of revenue on the basis of current or forecasted levels of usage.

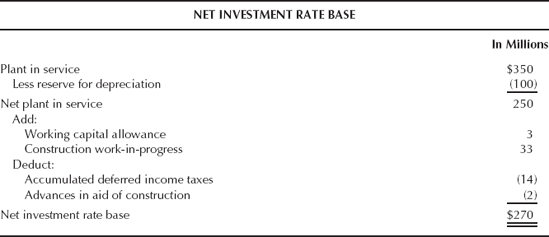

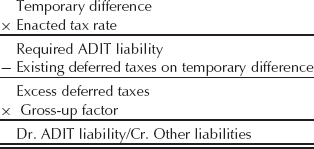

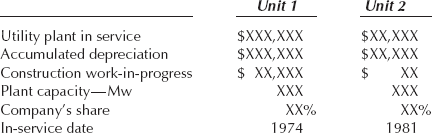

A utility earns a return on its rate base. Each investor-supplied dollar is entitled to such a return until the dollar is remitted to the investor. Some of the items generally included in the rate base computation are utility property and plant in service, a working capital allowance, and, in certain jurisdictions or circumstances, plant under construction. Generally, nonutility property, abandoned plant, plant acquisition adjustments, and plant held for future use are excluded. Deductions from rate base typically include the reserve for depreciation, accumulated deferred income taxeAccumulated Deferred Income Taxes (ADITs), which represent cost-free capital, certain unamortized deferred investment tax credits, and customer contributions in aid of construction. Exhibit 33.1 provides an example of the computations used to determine a rate base.

Various methods are used in valuing rate base. These methods apply to the valuation of property and plant and include these three:

Original cost

Fair value

Weighted cost

The original cost method, the most widely used method, corresponds to accounting principles generally accepted in the United States (GAAP), which require historical cost data for primary financial statement presentation. In addition, all regulatory commissions have adopted the USOA, requiring original cost for reporting purposes. Original cost is defined in the FERC's USOA as "the cost of such property to the person first devoting it to public service." This method was originally adopted by various commissions during the 1930s, at which time inflation was not a major concern.

The fair value method is defined as not the cost of assets but rather what they are really worth at the time rates are established. The following three methods of computing fair value are most often used:

Trended Cost. Utilizes either general or specific cost indices to adjust original cost.

Reproduction Cost New. A calculation of the cost to reproduce existing plant facilities at current costs.

Market Value. Involves the appraisal of specific types of plant.

The weighted cost method for valuation of property and plant is used in some jurisdictions as a compromise between the original cost and the fair value methods. Under this method, some weight is given to both original cost and fair value. Regulatory agencies in some weighted cost jurisdictions use a 50/50 weighting of original cost and fair value, whereas others use 60/40 or other combinations.

In a significant rate base case, Federal Power Commission v. Hope Natural Gas Co. [320 U.S. 591 (1944)], the original cost versus fair value controversy finally came to a head. A number of important points came out of this case, including the Doctrine of the End Result. The U.S. Supreme Court's decision did not approve original cost or fair value. Instead, it said a rate-making body can use any method, including no formula at all, so long as the end result is reasonable. It is not the theory but the impact of the theory that counts.

The rate of return is the rate determined by a regulator to be applied to the rate base to provide a fair return to investors. In the capital market, utilities must compete against nonregulated companies for investors' funds. Therefore, a fair rate of return to common equity investors is critical.

Different sources of capital with different costs are involved in establishing the allowed rate of return. Exhibits 33.2 and 33.3 show the computations used to determine the rate of return.

The cost of long-term debt and preferred stock is usually the "embedded" cost, that is, long-term debt issues have a specified interest rate, whereas preferred stock has a specified dividend rate. Computing the cost of equity is more complicated because there is no stated interest or dividend rate. Several methods have been used as a guide in setting a return on common equity. These methods reflect different approaches, such as earnings/price ratios, discounted cash flows, comparable earnings, and perceived investor risk.

The cost of each class of capital is weighed by the percentage that the class represents of the utility's total capitalization.

Two important cases provide the foundation for dealing with rate of return issues: Bluefield Water Works & Improvement Co. v. West Virginia Public Service Comm. [262 U.S. 679 (1923)] and the Hope Gas case. The important rate of return concepts that arise from these cases include the following five concepts:

A company is entitled to, but not guaranteed, a return on the value of its property.

Return should be equal to that earned by other companies with comparable risks.

A utility is not entitled to a return such as that earned by a speculative venture.

The return should be reasonably sufficient to:

Assure confidence and financial soundness of the utility.

Maintain and support its credit.

Enable the utility to raise additional capital.

Efficient and economical management is a prerequisite for profitable operations.

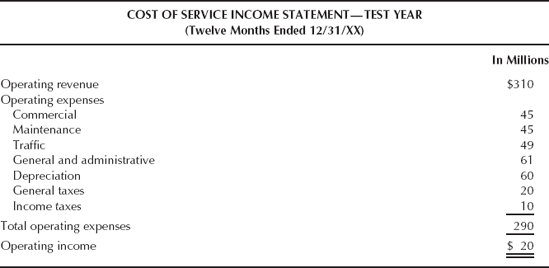

Operating income for purposes of establishing rates is computed based on test-year information, which is normally a recent or projected 12-month period. In either case, historic or projected test-year revenues are calculated based on the current rate structure in order to determine if there is a revenue requirement deficiency. The operating expense information generally includes most expired costs incurred by a utility. As illustrated in Exhibit 33.4, the operating expense information, after reflecting all necessary pro forma adjustments, determines operating income for rate-making purposes.

Above-the-line and below-the-line are frequently used expressions in public utility, financial, and regulatory circles. The above-the-line expenses on which operating income appears are those that ordinarily are directly included in the rate-making formula; below this line are the excluded expenses (and income). The principal cost that is charged below-the-line is interest on debt since it is included in the rate-making formula as a part of the rate-of-return computation and not as an operating expense. The inclusion or exclusion of a cost above-the-line is important to the utility since this determines whether it is directly includable in the rate-making formula as an operating expense.

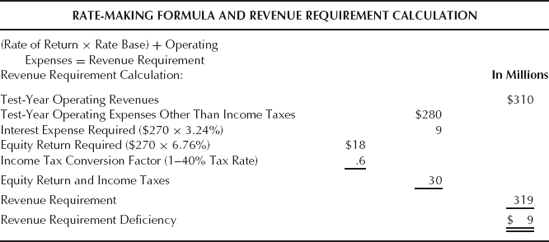

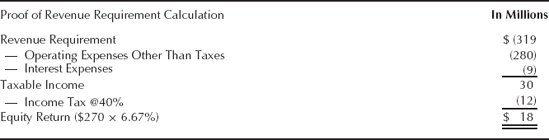

A significant consideration in determining the revenue requirement is that the rate of return computed is the rate after income taxes (which are a part of operating expenses). In calculating the revenue required, the equity return component of operating income (the equity return) (equity rate of return times rate base) deficiency must be grossed up for income taxes. This is most easily accomplished by dividing the equity return deficiency by the complement of the applicable income tax rate. For example, if the operating income deficiency is $5,000 and the income tax rate is 40 percent, the required revenue is $5,000/.6, or $8,333. By increasing revenues $8,333, income tax expense will increase by $3,333 ($8,333 × 40 percent), with the remainder increasing equity return by the deficiency amount of $5,000. This concept is illustrated as part of an example revenue requirement calculation based on the information presented in Exhibit 33.5. Exhibit 33.6 shows a proof of the revenue requirement calculation.

When the rate-making process is complete, the utility will set rate tariffs to recover $319 million. At this level, future revenues will recover $292 million of operating expenses (including income taxes of $12 million) and provide a return of $27 million. This return equates to a 10 percent earnings level on rate base. The $27 million operating income will go toward paying $9 million of interest on long-term debt ($130 million × 6.75 percent) and leaving net income for the common equity holders of $18 million—which approximates the desired 13 percent return on common equity of $140 million. However, the rate-making process only provides the opportunity to earn at that level. If future sales volumes, operating costs, or other factors change, the utility will earn more or less than the allowed amount.

As a result of changing market conditions and growing competition, alternative forms of regulation began to emerge in the late 1980s. There are many new and different forms of regulation, but they all generally share a common characteristic. Utilities are provided an opportunity to achieve and retain higher levels of earnings compared with traditional regulation. It is believed that this opportunity will fundamentally change the incentives under regulation for cost reductions and productivity improvement. Alternative forms of regulation also are intended, in some cases, to provide needed pricing flexibility for services in competitive markets.

Examples of alternative forms of regulation include:

Price ceilings or caps

Rate moratoriums

Sharing formulas

Regulated transition to competition

Price caps are essentially regulation of the prices of services. This contrasts with rate of return or cost-based regulation under which the costs and earnings levels of services are regulated.

The fundamental premise behind price cap regulation is that it provides utilities with positive incentives to reduce costs and improve productivity because shareholders can retain some or all of the resulting benefits from increased earnings. Under rate of return regulation, assuming simultaneous rate making, customers receive all of the benefits by way of reduced rates.

Typical features of price cap plans are these three:

A starting point for prices that is based on the rates that were previously in effect under rate of return regulation. Under some plans, adjustments may be made to beginning rates to correct historical pricing disparities with the costs of providing service.

The ability to subsequently adjust prices periodically up to a cap measured by a predetermined formula.

The price cap formula usually includes three components: the change in overall price levels, an offset for productivity gains, and exogenous cost changes.

The change in overall price levels is measured by some overall inflation index, such as the Gross National Product—Price Index or some variation of the Consumer Price Index.

The productivity offset is a percentage amount by which a regulated utility is expected to exceed the productivity gains experienced by the overall population measured by the inflation index. The combination of a change in price levels less the productivity offset can produce positive or negative price caps. As an example, if the change in price levels was +5.5 percent, and the productivity offset was 3.3 percent, a utility could increase its prices for a service by +2.2 percent.

There are also provisions to add or subtract the effects of exogenous cost changes from the formula. Exogenous changes are defined as those beyond the control of the company. Endogenous changes conversely are those assumed to be included in the overall price level change. Examples of exogenous items in certain jurisdictions might include changes in GAAP, environmental laws, or tax rates. Each regulatory jurisdiction's price cap plan may differ somewhat as to the definition of exogenous versus endogenous cost changes.

In their purest form, price caps are applied to determine rates, and the company retains the actual level of earnings the rates produce. However, most price cap plans also include backstop mechanisms. These include sharing earnings above a certain level with customers or for increasing rates if actual earnings fall below a specified level. Some plans also permit adjustment of rates above the price cap, subject to full cost justification and burden of proof standards.

Rate moratoriums are simply a freeze in prices for a specified period of time. In effect, rate moratoriums function like a price cap where the productivity offset is set equal to the change in price levels, yielding a price cap of 0 percent. Most rate moratorium plans have provisions to adjust prices for specified exogenous cost changes, although the definition of exogenous may be even more restrictive than under price cap plans.

Sharing formulas are often paired with traditional rate of return regulation as an interim true-up mechanism between rate proceedings or added to price cap or rate moratorium plans as a backstop.

Sharing usually involves the comparison of actual earnings levels (determined by applying the traditional regulatory and cost allocation processes) with an authorized rate of return. Earnings above specified intervals are shared between shareholders and customers based on some formula.

Sharing is accomplished in a variety of ways. Five of the more common forms are:

One-time cash refunds or bill credits to customers

Negative surcharges on customer bills for a specified time period

Adjustments to subsequent price cap formulas

Infrastructure investment requirements

Capital recovery offsets

Prior to the 2000–2001 energy crisis in California and the western United States, regulators in a number of states had adopted, or were in the process of adopting, legislation to change the traditional approach to the regulation of the generation portion of electric utility operations. The objective of this change was to provide customers with the right to choose their electricity supplier.

In simple terms, this legislation provides for a transition period from cost-based to market-based regulation. During this transition period, customers obtain the right to choose their electricity supplier at market price. Customers might also be charged a transition surcharge during the transition, which is intended to provide the electric utility with recovery of some or all of its electric generation stranded costs.

Stranded costs are often synonymous with high-cost generating units. However, they are more broadly defined to include other assets or expenses that, when recovered under traditional cost-based regulation, cause rates to exceed market prices. These costs can include regulatory assets and various obligations, such as for plant decommissioning, fuel contracts, or purchase power commitments.

At the end of the transition period, customers will be able to purchase electricity at market prices from their chosen supplier and the electric utility will be limited to providing transmission and distribution services at regulated prices.

Regulatory agencies with statutory authority to establish rates for utilities also prescribe the accounting that their jurisdictional regulated entities must follow. Accounting may be prescribed by a USOA, by periodic reporting requirements, or by accounting orders.

Because of the statutory authority of regulatory agencies over both accounting and rate setting of regulated utilities, some regulators, accountants, and others believe that the agencies have the final authority over the form and content of financial statements published by those utilities for their investors and creditors. This is the case even when the stockholders′ report, based on regulatory accounting requirements, would not be in accordance with GAAP.

Actually, this issue has not arisen frequently because regulators have usually reflected changes in GAAP in the USOA that they prescribe. For example, the USOA of the FCC has GAAP as its foundation, with departures being permitted as necessary, because of departures from GAAP in ratemaking. But the general willingness of regulators to conform to GAAP does not answer the question of whether a regulatory body has the final authority to prescribe the accounting to be followed for the financial statements included in the annual and other reports to stockholders or outsiders, even when such statements are not prepared in accordance with GAAP.

The landmark case in this area is the Appalachian Power Co. v. Federal Power Commission [328 F.2 d 237 (4th Cir.), cert. denied, 379 U.S. 829 (1964)]. The FPC (now the FERC) found that the financial statements in the annual report of the company were not in accordance with the accounting prescribed by the FPC's USOA. The FPC was upheld at the circuit court level in 1964 and the Supreme Court denied a writ of certiorari. The general interpretation of this case has been that the FPC had the authority to order that the financial statements in the annual report to stockholders of its jurisdictional utilities be prepared in accordance with the USOA, even if not in accordance with GAAP.

During subsequent years, the few differences that have arisen have been resolved without court action, and so it is not clear just what authority the FERC or other federal agencies may now have in this area. The FERC has not chosen to contest minor differences, and one particular utility, Montana Power Company, met the issue of FPC authority versus GAAP, by presenting, for several years, two balance sheets in its annual report to shareholders. One balance sheet was in accordance with GAAP, which reflected the rate making prescribed by the state commission, and one balance sheet was in accordance with the USOA of the FPC, which had ordered that certain assets be written off even though the state commission continued to allow them in the rate base. The company's auditors stated that the first balance sheet was in accordance with GAAP and that the second balance sheet was in accordance with the FPC USOA.

Since then the FERC has allowed a company to follow accounting that the FERC believes reflects the rate making even though the accounting does not comply with a standard of the Financial Accounting Standards BoardFinancial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). The SEC has ruled that the company must follow GAAP. As a result, the regulatory treatment was reformulated to meet the FASB standard, and so the conflict was resolved without going to the courts.

The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) has no financial reporting enforcement or disciplinary responsibility. Enforcement with regard to entities whose shares are traded in interstate commerce arises from SEC policy articulated in ASR No. 150, which specifies that FASB standards (and those of its predecessors) are required to be followed by registrants in their filings with the SEC. Thus, the interrelationship between the FASB and the SEC operates to achieve, virtually without exception for an entity whose securities trade in interstate commerce, the presentation of financial statements that reflect GAAP. Although this jurisdictional issue is neither resolved nor disappearing, it appears that the SEC currently exercises significant, if not controlling, influence over the general-purpose financial statements of all public companies, including regulated utilities.

Rate making on an individual cost-of-service basis is designed to permit a utility to recover its costs that are incurred in providing regulated services. Individual cost-of-service does not guarantee cost recovery. However, there is a much greater assurance of cost recovery under individual cost-of-service rate making than for enterprises in general. This likelihood of cost recoverability provides a basis for a different application of GAAP, which recognizes that rate making can affect accounting.

As such, a rate regulator's ability to recognize, not recognize, or defer recognition of revenues and costs in established rates of regulated utilities adds a unique consideration to the accounting and financial reporting of those enterprises. This unique economic dimension was first recognized by the accounting profession in paragraph 8 of ARB No. 44 (Revised), "Declining-Balance Depreciation":

Many regulatory authorities permit recognition of deferred income taxes for accounting and/or rate-making purposes, whereas some do not. The committee believes that they should permit the recognition of deferred income taxes for both purposes. However, where charges for deferred income taxes are not allowed for rate-making purposes, accounting recognition need not be given to the deferment of taxes if it may reasonably be expected that increased future income taxes, resulting from the earlier deduction of declining-balance depreciation for income-tax purposes only, will be allowed in the future rate determinations.

A year later, in connection with the general requirement to eliminate intercompany profits, paragraph 6 of ARB No. 51, "Consolidated Financial Statements," concluded:

However, in a regulated industry where a parent or subsidiary manufactures or constructs facilities for other companies in the consolidated group, the foregoing is not intended to require the elimination of intercompany profit to the extent that such profit is substantially equivalent to a reasonable return on investment ordinarily capitalized in accordance with the established practice of the industry.

In 1962, the APB decided to express its position on applicability of GAAP to regulated industries. The resulting statement, initially reported in The Journal of Accountancy in December 1962, later became the Addendum to APB Opinion No. 2, "Accounting for the Investment Credit" (the Addendum), and provided that:

GAAP applies to all companies—regulated and nonregulated.

Differences in the application of GAAP are permitted as a result of the rate-making process because the rate regulator creates economic value.

Cost deferral on the balance sheet to reflect the rate-making process is appropriately reflected on the balance sheet only when recovery is clear.

A regulatory accounting difference without ratemaking impact does not constitute GAAP. The accounting must be reflected in rates.

The financial statements of regulated entities other than those prepared for regulatory filings should be based on GAAP with appropriate recognition of rate-making consideration.

The Addendum provided the basis for utility accounting for almost 20 years. During this period, utilities accounted for certain items differently than enterprises in general. For example, regulators often treat capital leases as operating leases for rate purposes, thus excluding them from rate base and allowing only the lease payments as expense. In that event, regulated utilities usually treated such leases as operating leases for financial statement purposes. This resulted in lower operating expenses during the first few years of the lease.

Also, utilities capitalize both debt and equity components of funds used during construction, which is generally described as an allowance for funds used during constructionAllowance for Funds Used during Construction (AFUDC). The FASB, under SFAS No. 34, "Capitalization of Interest Cost," allows nonregulated companies to capitalize only the debt cost. Because property is by far the largest item in most utility companies′ balance sheets and because they do much of their own construction, the effect of capitalizing AFUDC is frequently very material to both the balance sheet and the statement of income.

Such differences, usually concerning the timing of recognition of a cost, were cited as evidence that the Addendum allowed almost any accounting treatment if directed by rate regulation. There was also some concern that the Addendum applied to certain industries that were regulated, but not on an individual cost-of-service basis. These as well as other issues ultimately led to the FASB issuing SFAS No. 71, "Accounting for the Effects of Certain Types of Regulation," which attempted to provide a clear conceptual basis to account for the economic impact of regulation, to emphasize the concept of one set of accounting principles for all enterprises, and to enhance the quality of financial reporting for regulated enterprises.

SFAS No. 71 specifies criteria for the applicability of the Statement by focusing on the nature of regulation rather than on specific industries. As stated in paragraph 5 of SFAS No. 71:

[T]his statement applies to general-purpose external financial statements of an enterprise that has regulated operations that meet all of the following criteria:

The enterprise's rates for regulated services or products provided to its customers are established by or are subject to approval by an independent, third-party regulator or by its own governing board empowered by statute or contract to establish rates that bind customers.

The regulated rates are designed to recover the specific enterprise's costs of providing the regulated services or products.

In view of the demand for the regulated services or products and the level of competition, direct and indirect, it is reasonable to assume that rates set at levels that will recover the enterprise's costs can be charged to and collected from customers. This criterion requires consideration of anticipated changes in levels of demand or competition during the recovery period for any capitalized costs.

Based on these criteria, SFAS No. 71 provides guidance in preparing general-purpose financial statements for most investor-owned, cooperative, and governmental utilities.

The FASB's sister entity, the GASB, has been empowered to set pervasive standards for government utilities to the extent applicable, and, accordingly, financial statements issued in accordance with GAAP must follow GASB standards. However, in the absence of an applicable pronouncement issued by the GASB, differences between accounting followed under GASB or other FASB pronouncements and accounting followed for rate-making purposes should be handled in accordance with SFAS No. 71.

After the issuance of SFAS No. 71, the FASB became concerned about the accounting being followed by utilities (primarily electric companies) for certain transactions. Significant economic events were occurring, including these three:

Disallowances of major portions of recently completed plants

Very large plant abandonments

Phase-in plans

All of these events in one way or another prevented utilities from recovering costs currently and, in some instances, did not allow recovery at all. As a result, the FASB amended SFAS No. 71 with SFAS No. 90, "Regulated Enterprises—Accounting for Abandonments and Disallowances of Plant Costs," and SFAS No. 92, "Regulated Enterprises—Accounting for Phase-In Plans." Also, SFAS No. 144, "Accounting for the Impairment or Disposal of Long-Lived Assets," amended SFAS No. 71 to require a continuing probability assessment for the recovery of regulatory assets.

Due to the increasing level of competition and deregulation faced by all types of rateregulated enterprises, the FASB issued SFAS No. 101, "Regulated Enterprises—Accounting for the Discontinuation of Application of FASB Statement 71." SFAS No. 101 addresses the accounting to be followed when SFAS No. 71 is discontinued. Related guidance is also set forth in the FASB's Emerging Issues Task ForceEmerging Issues Task Force (EITF) Issue No. 97-4, "Deregulation of the Pricing of Electricity—Issues Related to the Application of FASB Statements No. 71, Accounting for the Effects of Regulation and No. 101, Regulated Enterprises—Accounting for the Discontinuation of Application of FASB Statement No. 71."

The major issues addressed in SFAS No. 71 relate to the following:

Effect of rate making on GAAP

Evidence criteria for recording regulatory assets and liabilities

Application of GAAP to utilities

Proper financial statement disclosures

SFAS No. 71 sets forth (pars. 9–12) general standards of accounting for the effects of regulation. In addition, there are specific standards that are derived from the general standards and various examples (Appendix B) of the application of the general standards.

In SFAS No. 71, the FASB recognized that a principal consideration introduced by rate regulation is the cause-and-effect relationship of costs and revenues—an economic dimension that, in some circumstances, should affect accounting for regulated enterprises. Thus, a regulated utility should capitalize a cost (as a regulatory asset) or recognize an obligation (as a regulatory liability) if it is probable that, through the rate-making process, there will be a corresponding increase or decrease in future revenues. Regulatory assets and liabilities should be amortized over future periods consistent with the related increase or decrease, respectively, in future revenues.

Paragraph 9 of SFAS No. 71 states that the "rate action of a regulator can provide reasonable assurance of the existence of an asset." All or part of an incurred cost that would otherwise be charged to expense should be capitalized if:

It is probable that future revenues in an amount approximately equal to the capitalized cost will result from inclusion of that cost in allowable costs for rate-making purposes.

The regulator intends to provide for the recovery of that specific incurred cost rather than to provide for expected levels of similar future costs.

This general provision is not totally applicable to the regulatory treatment of costs of abandoned plants and phase-in plans. The accounting accorded these situations is specified in SFAS No. 90 and SFAS No. 92, respectively. EITF Issue No. 92-12, "Accounting for OPEB Costs by Rate Regulated Enterprises," addresses regulatory assets created in connection with the adoption of SFAS No. 106, "Employers" Accounting for Postretirement Benefits Other Than Pensions."

With these exceptions, SFAS No. 71 requires a rate-regulated utility to capitalize a cost that would otherwise be charged to expense if future recovery in rates is probable. Probable, as defined in SFAS No. 5, "Accounting for Contingencies," means likely to occur, a very high probability threshold. If, however, at any time the regulatory asset no longer meets the above criteria, the cost should be charged to earnings. This requirement results from an amendment to SFAS No. 71 included in SFAS No. 144. Thus, paragraph 9 mandates a probability of future recovery test to be met at each balance sheet date in order for a regulatory asset to remain recorded.

The terms "allowable costs" and "incurred costs," as defined in SFAS No. 71, also required further attention. The two terms were often applied interchangeably so that, in practice, the provisions of SFAS No. 71, paragraph 9, were interpreted to permit the cost of equity to be deferred and capitalized for future recovery as a regulatory asset. The FASB, in SFAS No. 92, concluded that equity return (or an allowance for earnings on shareholders′ investment) is not an incurred cost that would otherwise be charged to expense. Accordingly, such an allowance shall not be capitalized pursuant to paragraph 9 of SFAS No. 71.

An incurred cost that does not meet the asset recognition criteria in paragraph 9 of SFAS No. 71 at the date the cost is incurred should be recognized as a regulatory asset when it meets those criteria at a later date. Such guidance is set forth in EITF Issue No. 93-4, "Accounting for Regulatory Assets." SFAS No. 144 provides for previously disallowed costs that are subsequently allowed by a regulator to be recorded as an asset, consistent with the classification that would have resulted had the cost initially been included in allowable costs. This provision covers plant costs as well as regulatory assets. Additionally, SFAS No. 144 requires the carrying amount of a regulatory asset recognized pursuant to the criteria in paragraph 9 to be reduced to the extent the asset has been subsequently disallowed from allowable costs by a regulator.

The general standards also recognize that the rate action of a regulator can impose a liability on a regulated enterprise, usually to the utility's customers.

Following are three typical ways in which regulatory liabilities can be imposed:

A regulator may require refunds to customers (revenue collected subject to refund).

A regulator can provide current rates intended to recover costs that are expected to be incurred in the future. If those costs are not incurred, the regulator will reduce future rates by corresponding amounts.

A regulator can require that a gain or other reduction of net allowable costs be given to customers by amortizing such amounts to reduce future rates.

Paragraph 12 of the general standards states that "actions of a regulator can eliminate a liability only if the liability was imposed by actions of the regulator." The practical effect of this provision is that a utility's balance sheet should include all liabilities and obligations that an enterprise in general would record under GAAP, such as for capital leases, pension plans, compensated absences, and income taxes.

SFAS No. 71 also sets forth specific standards for several accounting and disclosure issues.

Paragraph 15 allows the capitalization of AFUDC, including a designated cost of equity funds, if a regulator requires such a method, rather than using SFAS No. 34 for purposes of capitalizing the carrying cost of construction.

Rate regulation has historically provided utilities with two methods of capturing and recovering the carrying cost of construction:

Capitalizing AFUDC for future recovery in rates

Recovering the carrying cost of construction in current rates by including construction work-in-progress in the utility's rate base

The computation of AFUDC is generally prescribed by the appropriate regulatory body. The predominant guidance has been provided by the FERC and FCC. The FERC has defined AFUDC as "the net cost for the period of construction of borrowed funds used for construction purposes and a reasonable rate on other funds when so used." The term other funds, as used in this definition, refers to equity capital.

The FERC formula for computing AFUDC is comprehensive and takes into consideration these five:

Debt and equity funds.

The levels of construction.

Short-term debt.

The costs of long-term debt and preferred stock are based on the traditional embedded cost approach, using the preceding year-end costs.

The cost rate for common equity is usually the rate granted in the most recent rate proceeding.

The FCC instructions also provide for equity and debt components. In allowing AFUDC, the FERC and FCC recognize that the capital carrying costs of the investments in construction work-in-progress are as much a cost of construction as other construction costs such as labor, materials, and contractors.

In contrast to regulated utilities, nonregulated companies are governed by a different standard, SFAS No. 34. Under the FASB guidelines:

[T]he amount of interest to be capitalized for qualifying assets is intended to be that portion of interest cost incurred during the assets acquisition periods that theoretically could have been avoided (for example, by avoiding additional borrowings or by using the funds expended for the assets to repay existing borrowings) if expenditures for the assets had not been made.

Furthermore, SFAS No. 34 allows only debt interest capitalization and does not recognize an equity component.

The specific standard in SFAS No. 71 states that capitalization of such financing costs can occur only if both of the following two criteria are met.

It is probable that future revenue in an amount at least equal to the capitalized cost will result from the inclusion of that cost in allowable costs for rate-making purposes.

The future revenue will be provided to permit recovery of the previously incurred cost rather than to provide for expected levels of similar future costs.

In practice, many have interpreted the standard under SFAS No. 71 to mean that AFUDC should be capitalized if it is reasonably possible (not necessarily probable under SFAS No. 5) that the costs will be recovered. This same reasoning was also applied to the capitalization of other incurred costs such as labor and materials. Thus, capitalization occurred so long as recovery was reasonably possible and a loss was not probable.

As previously indicated, SFAS No. 90 amends the definition of "probable" included in SFAS No. 71 such that "probable" is now defined under the stringent technical definition in SFAS No. 5. In addition, paragraph 8 of SFAS No. 90 clarified that AFUDC capitalized under paragraph 15 can occur only if "subsequent inclusion in allowable costs for rate-making purposes is probable." Accordingly, the standard for capitalizing AFUDC is different from the standard applied to other costs, such as labor and materials.

The FASB also concluded in SFAS No. 92, paragraph 66, that:

[I]f the specific criteria in paragraph 15 of SFAS No. 71 are met but AFUDC is not capitalized because its inclusion in the cost that will become the basis for future rates is not probable, the regulated utility may not alternatively capitalize interest cost in accordance with SFAS No. 34.

Paragraph 16 of SFAS No. 71 generally reaffirms the provision in ARB No. 51 that intercompany profits on sales to regulated affiliates should not be eliminated in general-purpose financial statements if the sales price is reasonable and it is probable that future revenues allowed through the rate-making process will approximately equal the sales price.

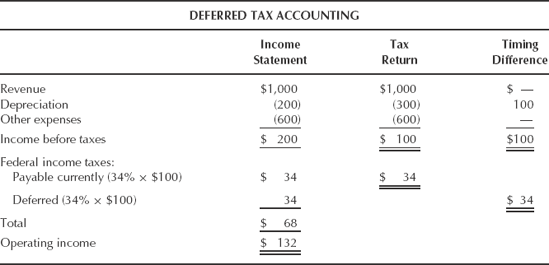

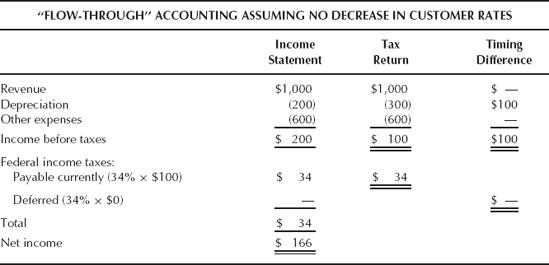

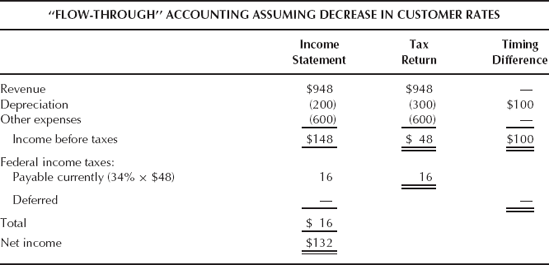

In paragraph 18 of SFAS No. 71, the FASB recognized that, in some cases, a regulator flows through the tax effects of certain timing differences as a reduction in future rates. In such cases, if it is probable that future rates will be based on income taxes payable at that time, SFAS No. 71 did not permit deferred taxes to be recorded in accordance with APB Opinion No. 11, "Accounting for Income Taxes."

In February 1992, SFAS No. 71 was amended by SFAS No. 109 and paragraph 18 was replaced by the following:

A deferred tax liability or asset shall be recognized for the deferred tax consequences of temporary differences in accordance with FASB Statement No. 109, "Accounting for Income Taxes."

Paragraph 19 of SFAS No. 71 addresses the accounting for significant refunds. Examples include refunds granted gas distribution utilities from pipelines and telephone refunds occurring where revenues are estimated in one period and "trued-up" at a later date or where revenues are billed under bond pending settlement of a rate proceeding.

For refunds recognized in a period other than the period in which the related revenue was recognized, disclosure of the effect on net income and the years in which the related revenue was recognized is required if material. SFAS No. 71 provides presentation guidance that the effect of such refunds may be disclosed by displaying the amount, net of income tax, as a line item in the income statement, but not as an extraordinary item.

Adjustments to prior quarters of the current fiscal year are appropriate for such refunds, provided all of the following three criteria are met:

The effect is material (either to operations or income trends).

All or part of the adjustment or settlement can be specifically identified with and is directly related to business activities of specific prior interim periods.

The amount could not be reasonably estimated prior to the current interim period but becomes reasonably estimable in the current period.

This treatment of prior interim periods for utility refunds is one of the restatement exceptions contained in paragraph 13 of SFAS No. 16, "Prior Period Adjustments."

Paragraph 20 of SFAS No. 71 requires disclosure of costs being amortized in accordance with the actions of a regulator but not being allowed to earn a return during the recovery period. Disclosure should include the remaining amounts being amortized (the amount of the nonearning asset) as well as the remaining recovery period.

Appendix B in SFAS No. 71 contains examples of the application of the general standards to specific situations. These examples, along with the basis for conclusions (Appendix C), are an important aid in understanding the provisions of SFAS No. 71 and the financial statements of utilities.

Items discussed include the following:

Intangible assets

Accounting changes

Early extinguishment of debt

Accounting for contingencies

Accounting for leases

Revenue collected subject to refund

Refunds to customers

Accounting for compensated absences

The provisions of SFAS No. 90 are limited to the narrow area of accounting for abandonments and disallowances of plant costs and not to other assets, regulatory or otherwise.

When a direct disallowance of a newly completed plant is probable and estimable, a loss should be recorded, dollar for dollar, for the disallowed amount. After the write-down is achieved, the reduced asset forms the basis for future depreciation charges.

An indirect disallowance occurs when, in certain circumstances, no return or a reduced return is permitted on all or a portion of the new plant for an extended period of time. To determine the loss resulting from an indirect disallowance, the present value of the future revenue stream allowed by the regulator should be determined by discounting at the most recent allowed rate of return. This amount should be compared with the recorded plant amount and the difference recorded as a loss. Under this discounting approach, the remaining asset should be depreciated consistent with the rate making and in a manner that would produce a constant return on the undepreciated asset equal to the discount rate.

In the case of abandonments, when no return or only a partial return is permitted, at the time the abandonment is both probable and estimable, the asset should be written off and a separate new asset should be established based on the present value of the future revenue stream. The entities" incremental borrowing rate should be used to measure the new asset. During the recovery period, the new asset should be amortized to produce zero net income based on the theoretical debt, and interest should be assumed to finance the abandonment. FTB No. 87-2, "Computation of a Loss on an Abandonment," supports discounting the abandonment revenue stream using an after-tax incremental borrowing rate.

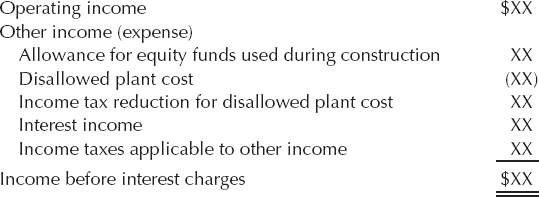

SAB No. 72 (currently cited as SAB Topic 10E) concludes that the effects of applying SFAS No. 90 should not be reported as an extraordinary item. SAB No. 72 states that such charges should be reported gross as a component of other income and deductions and not shown net-of-tax. The following presentation complies with the requirements of SAB No. 72:

A phase-in plan, as defined in SFAS No. 92, is a method of ratemaking that meets each of the following three criteria:

Adopted in connection with a major, newly completed plant of the regulated enterprise or one of its suppliers or a major plant scheduled for completion in the near future

Defers the rates intended to recover allowable costs beyond the period in which those allowable costs would be charged to expense under GAAP applicable to enterprises in general

Defers the rates intended to recover allowable costs beyond the period in which those rates would have been ordered under ratemaking methods routinely used prior to 1982 by that regulator for similar allowable costs of that utility

The phase-in definition includes virtually all deferrals associated with newly completed plant, such as rate levelization proposals, alternative methods of depreciation such as a sinking fund approach, rate treatment of capital leases as operating leases, and other schemes to defer new plant costs to the future. SFAS No. 92 specifically states that it applies to rate-making methods developed for "... major newly completed plant of the regulated enterprise or of one of its suppliers ..." Accordingly, SFAS No. 92 must be considered with respect to purchase power contracts.

Under the accounting provisions of SFAS No. 92, cost deferral under a phase-in plan is not permitted for plant/fixed assets on which substantial physical construction had not been performed before January 1, 1988. Consequently, for a major, newly completed plant that does not meet the January 1, 1988, cutoff date, post in-service deferrals for financial reporting purposes are limited to a time frame that ends when rates are adjusted to reflect the cost of operating the plant. This limitation, along with the restriction on modifying an existing phase-in plan, as discussed below, are the most important SFAS No. 92 provisions today.

As indicated above, SFAS No. 92 applies to the costs of a major, newly completed plant. There are situations in which a regulator subsequently starts to defer rates intended to recover allowable plant costs after return on and recovery of such costs have been previously provided. One example of this situation would occur when a regulator orders a future reduction in the depreciation rate (and rates charged to customers) of a 15-year-old nuclear generation plant, to factor in a potential 20-year license extension. Assuming that the new depreciation rate adopted by the regulator cannot be supported under GAAP (perhaps because the utility does not believe a license extension will occur), a regulatory deferral of plant costs (i.e., regulatory depreciation expense would be less than depreciation for financial reporting purposes) would result.

If the rate order was issued in connection with a major, newly completed plant, the guidance set forth in paragraph 35 of SFAS No. 92 presumes that the regulatory deferral of the "old" plant is equivalent to the regulatory deferral of the "new" plant. Thus, SFAS No. 92 must be applied. And, under that Statement, because the regulatory action results in a phase-in plan as defined in SFAS No. 92, no costs can be deferred for financial reporting purposes.

However, if the new rate order was not issued in connection with a major, newly completed plant and it is clear that the regulatory deferral relates only to "old" plant, SFAS No. 92 would not apply. Any deferral for financial reporting purposes must meet the requirements of SFAS No. 71, paragraph 9, for establishing and maintaining a regulatory asset. That determination should consider, as noted in paragraph 57 of SFAS No. 92, that the existence of such regulatory cost deferrals calls into question the applicability of SFAS No. 71.

If the phase-in plan meets all of the criteria required by SFAS No. 92, all allowable costs that are deferred for future recovery by the regulator under the plan should be capitalized for financial reporting as a separate asset. If any one of those criteria is not met, none of the allowable costs that are deferred for future recovery by the regulator under the plan should be capitalized.

The plan has been agreed to by the regulator.

The plan specifies when recovery will occur.

All allowable costs deferred under the plan are scheduled for recovery within 10 years of the date when deferrals begin.

The percentage increase in rates scheduled for each future year under the plan is not greater than the percentage increase in rates scheduled for each immediately preceding year.

When an existing phase-in plan is modified or a new plan is ordered to replace or supplement an existing plan, the above criteria should be applied to the combination of the modified plan and the existing plan. Thus, the 10-year period requirement, from when cost deferral commences until all costs are recovered, cannot be extended. If the recovery period is modified beyond 10 years, recorded costs under the phase-in plan should be immediately charged to earnings.

From a financial statement viewpoint, costs deferred should be classified and reported as a separate item in the income statement in the section relating to those costs. For instance, if capital costs are being deferred, they should be classified below-the-line. If depreciation or other operating costs are being deferred, the "credit" should be classified above-the-line with the operating costs. Allowable costs capitalized should not be reported net as a reduction of other expenses. Amortization of phase-in plan deferrals typically should be above-the-line (similar to recovering AFUDC via depreciation). This income statement presentation is consistent with guidance provided by the SEC 's staff in the "Official Minutes of the Emerging Issues Task Force Meeting" (February 23, 1989, Open Meeting).

SFAS No. 92 clarifies that AFUDC-equity can be capitalized in general purpose financial statements only during construction (based on par. 15 of SFAS No. 71) or as part of a qualifying phase-in plan. Thus, it is clear that, after January 1, 1988, AFUDC-equity can no longer be capitalized in connection with short-term rate synchronization deferrals. It should also be noted that, in connection with the adoption of SFAS No. 92, such deferrals can be recorded only when it is probable—based on SFAS No. 5—that such costs will be recovered in future rates. This is consistent with the discussion on SFAS No. 90 relating to capitalizing AFUDC.

Amounts deferred pursuant to SFAS No. 92 should also include an allowance for earnings on stockholders′ investment. If the phase-in plan meets the criteria in SFAS No. 92 and the regulator prevents the enterprise from recovering either some amount of its investment or some amount of return on its investment, a disallowance occurs that should be accounted for in accordance with SFAS No. 90.

A utility should disclose in its financial statements the terms of any phase-in plans in effect during the year. If a phase-in plan exists but does not meet the criteria in SFAS No. 92, the financial statements should include disclosure of the net amount deferred for rate-making purposes at the balance sheet date and the net change in deferrals for rate-making purposes during the year for those plans. In addition, the nature and amounts of any allowance for earnings on stockholders′ investment capitalized for rate-making purposes but not capitalized for financial reporting are to be disclosed.

The continuing applicability of SFAS No. 71 has been receiving more and more attention over the last 10 years, particularly with price cap regulation in the telecommunications industry and market-based or other alternative forms of pricing taking place in the pipeline and electric industries. Virtually every major telecommunications company that historically applied SFAS No. 71 has now discontinued applying it. Also, electric companies, including some of the largest in the industry, in various regulatory jurisdictions, have discontinued application of SFAS No. 71 for the generation portion of their operations as a result of the industry undergoing various fundamental changes. However, the changes are being revisited by many electric companies and their regulators as a result of the energy crisis in California that occurred in 2000 and early 2001. As a result, some companies have reapplied or are currently evaluating whether to reapply SFAS No. 71.

It is important that companies carefully review both the current and anticipated future rate environment to determine continued applicability of SFAS No. 71. In EITF Issue No. 97-4, a consensus was reached that the application of SFAS No. 71 to a segment of a rate-regulated enterprise's operations that is subject to a deregulation transition period should cease no later than the time when the legislation is passed or a rate order is issued and the related effects are known.

SFAS No. 101 gives several examples that may cause an enterprise to no longer meet the criteria for applying SFAS No. 71. Because virtually all regulated utilities are experiencing one or more of the examples cited below, it is important to make an evaluation of the continuing application of SFAS No. 71 at each balance sheet date.

Causes cited in SFAS No. 101 include: deregulation, a change from cost-based rate making to another form of regulation, increasing competition that limits the ability to recover costs, and regulatory actions that limit rate relief to a level insufficient to recover costs. Other stress signs that may indicate that SFAS No. 71 is no longer applicable include these eight:

Increasing amounts of regulatory assets, including systematic underdepreciation of assets and deferral of costs

Regulatory assets being consistently amortized over long periods, particularly if such assets relate to ongoing operating costs

Substantial regulatory disallowances

Increasing amounts of deferred costs not earning a return

Chronic excess capacity (e.g., generating capacity and/or readily available supplies) resulting in nonearning assets

Rates for services or per mcf or kWh which are currently, or forecasted in the future, to be higher than those of neighboring entities and/or alternative competitive energy sources

Significant disparity among the rates charged to residential, commercial, and industrial customers and rate concessions for major customers or segments

Stress accumulation and/or the actions of other to discontinue application of SFAS No. 71, making the specialized regulatory accounting model no longer creditable

These examples provide warning signs and are not meant as hard and fast rules. Instead, considerable judgment is required to determine when an enterprise ceases to meet the criteria of SFAS No. 71. However, we believe there are two trigger points that generally indicate an enterprise no longer meets the criteria of SFAS No. 71:

If the current form of rate regulation results in an extended rate moratorium or a regulatory process that precludes the enterprise for an extended period (in excess of five years) from adjusting rates to reflect the utility's cost of providing service

The regulatory process results or is expected to result in the utility earning significantly less (250–300 basis points) than its allowed or a reasonable current rate of return for an extended period of time (three or four years)

Once a utility concludes that all or a part of a company's operations no longer comes under SFAS No. 71, it should discontinue application of that Statement and report discontinuation by eliminating from its balance sheet the effects of any actions of regulators that had been recognized as assets and liabilities pursuant to SFAS No. 71 but would not have been recognized as assets and liabilities by enterprises in general. The guidance in SFAS No. 101 indicates that all regulatory-created assets and liabilities should be written off unless the right to receive payment or the obligation to pay exists as a result of past events and regardless of expected future transactions.

Five examples of such regulatory-created assets and liabilities include:

Deferred storm damage

Deferred plant abandonment loss

Receivables or payables to future customers under purchased gas or fuel adjustment clauses (unless amounts are receivable or payable regardless of future sales)

Deferred gains or losses or reacquisition of debt

Revenues subject to refund as future sales price adjustments

SFAS No. 101 specifies that, if a separable portion of a rate-regulated utility's operations within a regulatory jurisdiction ceases to meet the criteria for application of SFAS No. 71, application of SFAS No. 71 to that separable portion should be discontinued. In EITF Issue No. 97-4, a consensus was reached that regulatory assets and liabilities should be recorded based on the separable portion of the operation from which the regulated cash flows to realize and settle them will be derived, rather than based on the separable portion initially incurring such costs. The consensus applies not only to regulatory assets and liabilities existing when the separable portion ceases application of SFAS No. 71, but also to regulatory assets and liabilities or any other costs of that separable portion that are probable of recovery, regardless of when incurred.

SFAS No. 101 also states:

However, the carrying amounts of plant, equipment, and inventory measured and reported pursuant to SFAS No. 71 should not be adjusted unless those assets are impaired (as measured by enterprises in general), in which case the carrying amounts of those assets should be reduced to reflect that impairment.

The carrying amount of inventories measured and reported pursuant to SFAS No. 71 would not be adjusted—to eliminate, for example, intercompany profit—absent loss recognition by applying the "cost or market, whichever is lower" rule set forth in Chapter 4, "Inventory Pricing," of ARB No. 43, "Restatement and Revision of Accounting Research Bulletins."

Reaccounting is required for true regulatory assets that have been misclassified as part of plant, such as postconstruction cost deferrals recorded as part of plant, and for systematic underdepreciation of plant in accordance with rate-making practices.

An apparent requirement of SFAS No. 101 when SFAS No. 71 is discontinued is that net-of-tax AFUDC should be displayed gross along with the associated deferred income taxes. This requirement is based on the notion that the net-of-tax AFUDC presentation is pursuant to industry practice and not SFAS No. 71. The interaction of this requirement along with the SFAS No. 101 treatment of excess deferred income taxes and the transition provision in SFAS No. 109 must be considered in connection with discontinuing the application of SFAS No. 71.

A utility might consider changing its method of accounting for investment tax credits in connection with adopting SFAS No. 101. Paragraph 11 of APB Opinion No. 4, "Accounting for the Investment Credit," as well as The Revenue Act of 1971 and U.S. Treasury releases, have required specific, full disclosure of the accounting method followed for ITC—either the flow-through method or the deferral method. Paragraph 16 of APB Opinion No. 20, "Accounting Changes," specifies that the previously adopted method of accounting for ITC should not be changed after the ITC has been discontinued or terminated. Therefore, the method of accounting used for ITC reported in financial statements when the Tax Reform Act of 1986 was signed, and such credits were discontinued, must be continued for those tax credits. Paragraph 4 of Accounting Interpretations of APB No. 4 indicates that the above guidance would apply to old ITC, even if a new similar credit were later enacted.

The net effect of the above adjustments should be included in income of the period of the change and classified as an extraordinary item in the income statement.

As noted in paragraph 43 of SFAS No. 101, the FASB concluded that the accounting for the reapplication of SFAS No. 71 is beyond the scope of SFAS No. 101. However, there have been several companies that have reapplied SFAS No. 71, including at least one registrant that precleared its accounting with the SEC staff.

When facts and circumstances change so that a utility's regulated operations meet all of the criteria set forth in paragraph 5 of SFAS No. 71, that Statement should be reapplied to all or a separable portion of its operations, as appropriate.

Reapplication includes adjusting the balance sheet for amounts that meet the definition of a regulatory asset or regulatory liability in paragraphs 9 and 11, respectively, of SFAS No. 71. AFUDC should commence to be recorded if it is probable of future recovery, consistent with paragraph 15 of SFAS No. 71. Plant balances should not be adjusted for any difference that resulted from capitalizing interest under SFAS No. 34 instead of AFUDC while SFAS No. 71 was discontinued. Instead, a regulatory asset should be recorded if supportable As provided for in SFAS No. 144, previously disallowed costs that are subsequently allowed by a regulator should be recorded as an asset, consistent with the classification that would have resulted had these costs initially been allowed.

In practice, the net effect of the adjustments to reapply SFAS No. 71 have been classified as an extraordinary item in the income statement.

In recent years the SEC's staff has focused on electric utility restructuring and its effect on financial reporting. As a result, the appropriateness of the continuing application of SFAS No. 71 became a serious issue during the 1990s. Specifically, the SEC staff challenged the continued applicability of SFAS No. 71 by registrants in states where plans transitioning to market-based pricing/competition for electric generation were being formulated.

The SEC staff's concerns initially resulted from enacted legislation in California that provided at that time for transition to a competitive electric generation market. These concerns led to the identification of several unresolved issues concerning when SFAS No. 71 should be discontinued and how SFAS No. 101 should be adopted. A consensus was reached on each of the three major issues identified in Issue No. 97-4.

The first issue addresses when an enterprise should stop applying SFAS No. 71 to the separable portion of its business whose product or service pricing is being deregulated. However, this issue was limited to situations in which final legislation is passed or a rate order is issued that has the effect of transitioning from cost-based to market-based rates. In such situations, should SFAS No. 71 be discontinued at the beginning or the end of the transition period?

The EITF concluded that when deregulatory legislation or a rate order is issued that contains sufficient detail to reasonably determine how the transition plan will effect the separable portion of the business, SFAS No. 71 should be discontinued for that separable portion. Thus, SFAS No. 71 should be discontinued at the beginning (not the end) of the transition period.

Once SFAS No. 71 is no longer applied to a separable portion of an enterprise, the financial statements should segregate, via financial statement display or footnote disclosure, the amounts contained in the financial statements that relate to that separable portion.

The scope of the EITF's final consensus for Issue No. 97-4 was limited to a specific circumstance in which deregulatory legislation is passed and a final rate order issued. The EITF did not address the broader issue of whether the application of SFAS No. 71 should cease prior to final passage of deregulatory legislation or issuance of a final rate order.

Some relevant guidance for this situation is set forth in Paragraph 69 of SFAS No. 71, which states:

The Board concluded that users of financial statements should be aware of the possibilities of rapid, unanticipated changes in an industry, but accounting should not be based on such possibilities unless their occurrence is considered probable. [emphasis added]

Based on this guidance, once it becomes probable that the deregulation legislative and/or regulatory changes will occur and the effects are known in sufficient detail, SFAS No. 101 should be adopted.

If the start of the transition period is delayed and uncertainty exists because of an appeal process, it seems reasonable that the application of SFAS No. 71 should continue until the completion of such process and the change to market-based regulation becomes probable. However, if or when it is probable that the appeal will be denied and the change to market-based regulation ultimately enacted, the discontinuance of SFAS No. 71 and adoption of SFAS No. 101 should not be delayed.