Chapter 5

Reporting Profit or Loss in the Income Statement

IN THIS CHAPTER

Looking at typical income statements

Being an active reader of income statements

Asking about the substance of profit

Handling out-of-the-ordinary gains and losses in an income statement

Correcting misconceptions about profit

In this chapter, I lift up the hood and explain how the profit engine runs. Making a profit is the main financial goal of a business. (Not-for-profit organizations and government entities don’t aim to make profit, but they should break even and avoid a deficit.) Accountants are the profit scorekeepers in the business world and are tasked with measuring the most important financial number of a business. I should warn you right here that measuring profit is a challenge in most situations. Determining the correct amounts for revenue and expenses (and for special gains and losses, if any) to record is no walk in the park.

Managers have the demanding tasks of making sales and controlling expenses, and accountants have the tough job of measuring revenue and expenses and preparing financial reports that summarize the profit-making activities. Also, accountants are called on to help business managers analyze profit for decision-making, which I explain in Chapters 12 and 13. And accountants prepare profit budgets for managers, which I cover in Chapter 14.

This chapter explains how profit-making activities are reported in a business’s external financial reports to its owners and lenders. Revenue and expenses change the financial condition of the business, a fact often overlooked when reading a profit report. Keep in mind that recording revenue and expenses (and gains and losses) and then reporting these profit-making activities in external financial reports are governed by authoritative accounting standards, which I discuss in Chapter 2.

Presenting Typical Income Statements

At the risk of oversimplification, I would say that businesses make profit in three basic ways:

- Selling products (with allied services) and controlling the cost of the products sold and other operating costs

- Selling services and controlling the cost of providing the services and other operating costs

- Investing in assets that generate investment income and market value gains and controlling operating costs

Obviously, this list isn’t exhaustive, but it captures a large swath of business activity. In this chapter, I show you typical externally reported income statements for the three types of businesses. Products range from automobiles to computers to food to clothes to jewelry. The customers of a company that sells products may be final consumers in the economic chain, or a business may sell to other businesses. Services range from transportation to entertainment to consulting. Investment businesses range from mutual funds to credit unions to banks to real estate development companies.

Looking at businesses that sell products

Figure 5-1 presents a classic profit report for a product-oriented business; this report, called the income statement, would be sent to its outside, or external, owners and lenders. (The report could just as easily be called the net income statement because the bottom-line profit term preferred by accountants is net income, but the word net is dropped from the title, and it’s most often called the income statement.) Alternative titles for the external profit report include earnings statement, operating statement, statement of operating results, and statement of earnings. Note: Profit reports prepared for managers that stay inside a business are usually called P&L (profit and loss) statements, but this moniker isn’t used much in external financial reporting.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 5-1: Typical income statement for a business that sells products.

The heading of an income statement identifies the business (which in this example is incorporated — thus the “Inc.” following the name), the financial statement title (“Income Statement”), and the time period summarized by the statement (“Year Ended December 31, 2017”). I explain the legal organization structures of businesses in Chapter 4.

You may be tempted to start reading an income statement at the bottom line. But this financial report is designed for you to read from the top line (sales revenue) and proceed down to the last — the bottom line (net income). Each step down the ladder in an income statement involves the deduction of an expense. In Figure 5-1, four expenses are deducted from the sales revenue amount, and four profit lines are given: gross margin, operating earnings, earnings before income tax, and net income:

- Gross margin (also called gross profit) = sales revenue minus the cost of goods (products) sold expense but before operating and other expenses are considered

- Operating earnings (or loss) = profit (or loss) before interest and income tax expenses are deducted from gross margin

- Earnings (or loss) before income tax = profit (or loss) after deducting interest expense from operating earnings but before income tax expense

- Net income = final profit for period after deducting all expenses from sales revenue, which is commonly called the “bottom line”

Although you see income statements with fewer than four profit lines, you seldom see an income statement with more.

Terminology in income statements varies somewhat from business to business, but you can usually determine the meaning of a term from its context and placement in the income statement.

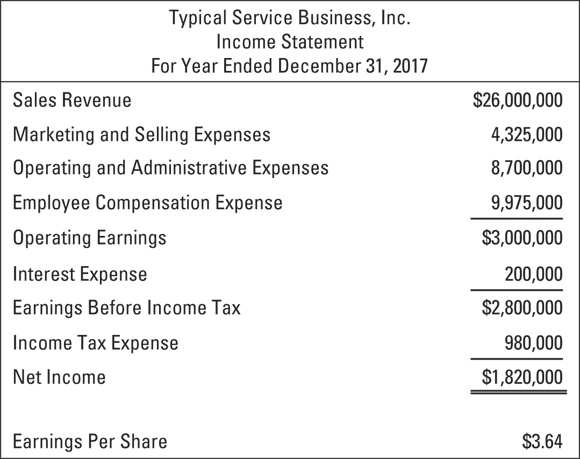

Looking at businesses that sell services

Figure 5-2 presents a typical income statement for a service-oriented business. I keep the sales revenue and operating earnings the same amount for both the product and the service businesses so you can more easily compare the two.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 5-2: Typical income statement for a business that sells services.

If a business sells services and doesn’t sell products, it doesn’t have a cost of goods sold expense; therefore, the company doesn’t show a gross margin line. Some service businesses report a cost of sales expense line, but this isn’t uniform at all. Even if they do, the business might not deduct this expense line from sales revenue to show a gross margin line equivalent to the one product companies report.

In Figure 5-2, the first profit line is operating earnings, which is profit before interest and income tax. The service business example in Figure 5-2 discloses three broad types of expenses. In passing, you may notice that the interest expense for the service business is lower than for the product business (compare with Figure 5-1). Therefore, it has higher earnings before income tax and higher net income.

Public companies must disclose certain expenses in their publicly available fillings with the federal Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Filing reports to the SEC is one thing; in their reports to shareholders, most businesses are relatively stingy regarding how many expenses are revealed in their income statements.

Looking at investment businesses

Figure 5-3 presents an income statement for an investment business. Notice that this income statement discloses three types of revenue: interest and dividends that were earned, gains from sales of investments during the year, and unrealized gains of the market value of its investment portfolio. Instead of gains, the business could’ve had realized and unrealized losses during a down year, of course. Generally, investment businesses are either required or are under a good deal of pressure to report their three types of investment return. Investment companies might not borrow money and thus have no interest expense. Or they might. I show interest expense in Figure 5-3 for the investment business example.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 5-3: Typical income statement for an investment business.

Taking Care of Housekeeping Details

- Minus signs are missing. Expenses are deductions from sales revenue, but hardly ever do you see minus signs in front of expense amounts to indicate that they’re deductions. Forget about minus signs in income statements and in other financial statements as well. Sometimes parentheses are put around a deduction to signal that it’s a negative number, but that’s the most you can expect to see.

- Your eye is drawn to the bottom line. Putting a double underline under the final (bottom-line) profit number for emphasis is common practice but not universal. Instead, net income may be shown in bold type. You generally don’t see anything as garish as a fat arrow pointing to the profit number or a big smiley encircling the profit number — but again, tastes vary.

- Profit isn’t usually called profit. As you see in Figures 5-1, 5-2, and 5-3, bottom-line profit is called net income. Businesses use other terms as well, such as net earnings or just earnings. (Can’t accountants agree on anything?) In this book, I use the terms net income and profit interchangeably, but when showing a formal income statement, I stick to “net income.”

You don’t get details about sales revenue. The sales revenue amount in an income statements of a product or a service company is the combined total of all sales during the year; you can’t tell how many different sales were made, how many different customers the company sold products or services to, or how the sales were distributed over the 12 months of the year. (Public companies are required to release quarterly income statements during the year, and they include a special summary of quarter-by-quarter results in their annual financial reports; private businesses may or may not release quarterly sales data.) Sales revenue does not include sales and excise taxes that the business collects from its customers and remits to the government.

Note: In addition to sales revenue from selling products and/or services, a business may have income from other sources. For instance, a business may have earnings from investments in marketable securities. In its income statement, investment income goes on a separate line and is not commingled with sales revenue. (The businesses featured in Figures 5-1 and 5-2 do not have investment income.)

Gross margin matters. The cost of goods sold expense of a business that sells products is the cost of products sold to customers, the sales revenue of which is reported on the sales revenue line. The idea is to match up the sales revenue of goods sold with the cost of goods sold and show the gross margin (also called gross profit), which is the profit before other expenses are deducted. The other expenses could in total be more than gross margin, in which case the business would have a net loss for the period. (By the way, a bottom-line loss usually has parentheses around it to emphasize that it’s a negative number.)

Note: Companies that sell services rather than products (such as airlines, movie theaters, and CPA firms) do not have a cost of goods sold expense line in their income statements, as you see in Figure 5-2. Nevertheless, some service companies report a cost of sales expense, and these businesses may also report a corresponding gross margin line of sorts. This is one more example of the variation in financial reporting from business to business that you have to live with if you read financial reports.

- Operating costs are lumped together. The broad category selling, general, and administrative expenses (refer to Figure 5-1) consists of a wide variety of costs of operating the business and making sales. Some examples are

- Labor costs (employee wages and salaries, plus retirement benefits, health insurance, and payroll taxes paid by the business)

- Insurance premiums

- Property taxes on buildings and land

- Cost of gas and electric utilities

- Travel and entertainment costs

- Telephone and Internet charges

- Depreciation of operating assets that are used more than one year (including buildings, land improvements, cars and trucks, computers, office furniture, tools and machinery, and shelving)

- Advertising and sales promotion expenditures

- Legal and audit costs

As with sales revenue, you don’t get much detail about operating expenses in a typical income statement as it’s presented to the company’s debtholders and shareholders. A business may disclose more information than you see in its income statement — mainly in the footnotes that are included with its financial statements. (I explain footnotes in Chapter 9.) Public companies have to include more detail about the expenses in their filings with the SEC, which are available to anyone who looks up the information (probably over the Internet).

Being an Active Reader

The worst thing you can do when presented with an income statement is to be a passive reader. You should be inquisitive. An income statement is not fulfilling its purpose unless you grab it by its numbers and start asking questions.

For example, you should be curious regarding the size of the business (see the nearby sidebar “How big is a big business, and how small is a small business?”). Another question to ask is “How does profit compare with sales revenue for the year?” Profit (net income) equals what’s left over from sales revenue after you deduct all expenses. The business featured in Figure 5-1 squeezed $1.69 million profit from its $26 million sales revenue for the year, which equals 6.5 percent. (The service business did a little better; see Figure 5-2.) This ratio of profit to sales revenue means expenses absorbed 93.5 percent of sales revenue. Although it may seem rather thin, a 6.5 percent profit margin on sales is quite acceptable for many businesses. (Some businesses consistently make a bottom-line profit of 10 to 20 percent of sales, and others are satisfied with a 1 or 2 percent profit on sales revenue.) Profit ratios on sales vary widely from industry to industry.

In the product business example in Figure 5-1, expenses such as labor costs and advertising expenditures are buried in the all-inclusive selling, general, and administrative expenses line. (If the business manufactures the products it sells instead of buying them from another business, a good part of its annual labor cost is included in its cost of goods sold expense.) Some companies disclose specific expenses such as advertising and marketing costs, research and development costs, and other significant expenses. In short, income statement expense-disclosure practices vary considerably from business to business.

Another set of questions you should ask in reading an income statement concerns the profit performance of the business. Refer again to the product company’s profit performance report (Figure 5-1). Profitwise, how did the business do? Underneath this question is the implicit question “Relative to what?” Generally speaking, three sorts of benchmarks are used for evaluating profit performance:

- Broad, industrywide performance averages

- Immediate competitors’ performances

- The business’s own performance in recent years

Deconstructing Profit

Now that you’ve had the opportunity to read an income statement (see Figures 5-1, 5-2, and 5-3), let me ask you a question: What is profit? My guess is that you’ll answer that profit is revenue less expenses. In my class, you’d get only a “C” grade for this answer. Your answer is correct, as far as it goes, but it doesn’t go far enough. This answer doesn’t strike at the core of profit. The answer doesn’t tell me what profit consists of or the substance of profit.

In this section, I explain the anatomy of profit. Having read the product company’s income statement, you now know that the business earned net income for the year ending December 31, 2017 (see Figure 5-1). Where’s the profit? If you had to put your finger on the profit, where would you touch?

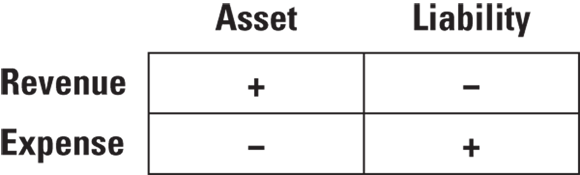

Recording profit works like a pair of scissors: You have the positive revenue blade and the negative expenses blade. Revenue and expenses have opposite effects. This leads to two questions: What is a revenue? And what is an expense?

Figure 5-4 summarizes the financial natures of revenue and expenses in terms of impacts on assets and liabilities. Notice the symmetrical framework of revenue and expenses. It’s beautiful in its own way, don’t you think? In any case, this summary framework is helpful for understanding the financial effects of revenue and expenses.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 5-4: Fundamental natures of revenue and expenses.

Revenue and expense effects on assets and liabilities

Here’s the gist of the two-by-two matrix shown in Figure 5-4. In recording a sale, the bookkeeper increases a revenue account. The revenue account accumulates sale after sale during the period. So at the end of the period, the total sales revenue for the period is the balance in the account. This amount is the cumulative end-of-period total of all sales during the period. All sales revenue accounts are combined for the period, and one grand total is reported in the income statement on the top line. As each sale (or other type of revenue event) is recorded, either an asset account is increased or a liability account is decreased.

Recording expenses is rather straightforward. When an expense is recorded, a specific expense account is increased, and either an asset account is decreased or a liability account is increased the same amount. For example, to record the cost of goods sold, the expense with this name is increased, say, $35,000, and in the same entry, the inventory asset account is decreased $35,000. Alternatively, an expense entry may involve a liability account instead of an asset account. For example, suppose the business receives a $10,000 bill from its CPA auditor that it will pay later. In recording the bill from the CPA, the audit expense account is increased $10,000, and a liability account called accounts payable is increased $10,000.

The summary framework of Figure 5-4 has no exceptions. Recording revenue and expenses (as well as gains and losses) always follow these rules. So where does this leave you for understanding profit? Profit itself doesn’t show up in Figure 5-4, does it? Profit depends on amounts recorded for revenue and expenses, of course, as I show in the next section.

Comparing three scenarios of profit

Figure 5-5 presents three scenarios of profit in terms of changes in the assets and liabilities of a business. In all three cases, the business makes the same amount of profit: $10, as you see in the abbreviated income statements on the right side. (I keep the numbers small, but you can think of $10 million instead of $10 if you prefer.)

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 5-5: Comparing asset and liability changes for three profit scenarios.

To find the amount of profit, first determine the amount of revenue and expenses for each case. In all three cases, total expenses are $90, but the changes in assets and liabilities differ:

- In Case 1, revenue consists of $100 asset increases; no liability was involved in recording revenue.

- In Case 2, revenue was from $100 decreases in a liability.

- In Case 3, you see both asset increases and liability decreases for revenue.

Some businesses make sales for cash; cash is received at the time of the sale. In recording these sales, a revenue account is increased and the cash account is increased. Some expenses are recorded at the time of cutting a check to pay the expense. In recording these expenses, an appropriate expense account is increased and the cash asset account is decreased. However, for most businesses, the majority of their revenue and expense transactions do not simultaneously affect cash.

For most businesses, cash comes into play before or after revenue and expenses are recorded. For example, a business buys products from its supplier that it will sell sometime later to its customers. The purchase is paid for before the goods are sold. No expense is recorded until products are sold. Here’s another example: A business makes sales on credit to its customers. In recording credit sales, a sales revenue account is increased and an asset account called accounts receivable is increased. Sometime later, the receivables are collected in cash. The amount of cash actually collected through the end of the period may be less than the amount of sales revenue recorded.

This chapter lays the foundation for Chapter 7, where I explain cash flow from profit. Cash flow is an enormously important topic in every business. I’m sure even Apple, with its huge treasure of marketable investments, worries about its cash flow.

Folding profit into retained earnings

The $40 increase on the asset side is balanced by the $30 increase in liabilities and the $10 increase in retained earnings on the opposite side of the accounting equation. The books are in balance.

In most situations, not all annual profit is distributed to owners; some is retained in the business. Unfortunately, the retained earnings account sounds like an asset in the minds of many people. It isn’t! It’s a source-of-assets account, not an asset account. It’s on the right-hand side of the accounting equation; assets are on the left side. For more information, see the sidebar “So why is it called retained earnings?”

The product business in Figure 5-1 earned $1.69 million profit for the year. Therefore, during the year, its retained earnings increased this amount because net income is recorded in this owners’ equity account. You know this for sure, but what you can’t tell from the income statement is how the assets and liabilities of the business were affected by its sale and expense activities during the period. The product company’s $1.69 million net income resulted in some mixture of changes in its assets and liabilities, such that its owners’ equity increased $1.69 million. Could be that its assets increased $1.0 million and its liabilities increased $0.69 million, but you can’t tell this from the income statement.

Pinpointing the Assets and Liabilities Used to Record Revenue and Expenses

The sales and expense activities of a business involve cash inflows and outflows, as I’m sure you know. What you may not know, however, is that the profit-making activities of a business that sells products on credit involves four other basic assets and three basic types of liabilities. Cash is the pivotal asset. You may have heard the old saying that “all roads lead to Rome.” In like manner, revenue and expenses, sooner or later, lead to cash. But in the meantime, other asset and liability accounts are used to record the flow of profit activity. This section explains the main assets and liabilities used in recording revenue and expenses.

Making sales: Accounts receivable and deferred revenue

In contrast to making sales on credit, some businesses collect cash before they deliver their products or services to customers. For example, I pay The New York Times for a one-year subscription at the start of the year. During the year, the newspaper “delivers” the product one day at a time. Another example is when you buy and pay for an airline ticket days or weeks ahead of your flight. There are many examples of advance payments by customers. When a business receives advance payments from customers, it increases cash (of course) and increases a liability account called deferred revenue. Sales revenue isn’t recorded until the product or service is delivered to the customer. When delivered sales revenue is increased, the liability account is decreased, which reflects that part of the liability has been “paid down” by delivery of the product or service.

Selling products: Inventory

The cost of goods sold is one of the primary expenses of businesses that sell products. (In Figure 5-1, notice that this expense equals more than half the sales revenue for the year.) This expense is just what its name implies: the cost that a business pays for the products it sells to customers. A business makes profit by setting its sales prices high enough to cover the costs of products sold, the costs of operating the business, interest on borrowed money, and income taxes (assuming that the business pays income tax), with something left over for profit.

When the business acquires products (by purchase or manufacture), the cost of the products goes into an inventory asset account (and, of course, the cost is either deducted from the cash account or added to a liability account, depending on whether the business pays cash or buys on credit). When a customer buys that product, the business transfers the cost of the products sold from the inventory asset account to the cost of goods sold expense account because the products are no longer in the business’s inventory; the products have been delivered to the customer.

In the first layer in the income statement of a product company, the cost of goods sold expense is deducted from the sales revenue for the goods sold. Almost all businesses that sell products report the cost of goods sold as a separate expense in their income statements, as you see in Figure 5-1. Most report this expense as shown in Figure 5-1 so that gross margin is reported. But some product companies simply report cost of goods sold as one expense among many and do not call attention to gross margin. Actually, you see many variations on the theme of reporting gross margin. Some businesses use the broader term “cost of sales,” which includes cost of goods sold as well as other costs.

Prepaying operating costs: Prepaid expenses

Prepaid expenses are the opposite of unpaid expenses. For example, a business buys fire insurance and general liability insurance (in case a customer who slips on a wet floor or is insulted by a careless salesperson sues the business). Insurance premiums must be paid ahead of time, before coverage starts. The premium cost is allocated to expense in the actual periods benefited. At the end of the year, the business may be only halfway through the insurance coverage period, so it should allocate only half the premium cost as an expense. (For a six-month policy, you charge one-sixth of the premium cost to each of the six months covered.) At the time the premium is paid, the entire amount is recorded as an increase in the prepaid expenses asset account. For each period of coverage, the appropriate fraction of the cost is recorded as a decrease in the asset account and as an increase in the insurance expense account.

In another example, a business pays cash to stock up on office supplies that it may not use up for several months. The cost is recorded in the prepaid expenses asset account at the time of purchase; when the supplies are used, the appropriate amount is subtracted from the prepaid expenses asset account and recorded in the office supplies expense account.

Fixed assets: depreciation expense

Long-term operating assets that are not held for sale in the ordinary course of business are called generically fixed assets; these include buildings, machinery, office equipment, vehicles, computers and data-processing equipment, shelving and cabinets, and so on. The term fixed assets is informal, or accounting slang. The more formal term used in financial reports is property, plant, and equipment. It’s easier to say fixed assets, which I do in this section.

Depreciation refers to spreading out the cost of a fixed asset over the years of its useful life to a business, instead of charging the entire cost to expense in the year of purchase. That way, each year of use bears a share of the total cost. For example, autos and light trucks are typically depreciated over five years; the idea is to charge a fraction of the total cost to depreciation expense during each of the five years. (The actual fraction each year depends on the method of depreciation used, which I explain in Chapter 8.)

Unpaid expenses: Accounts payable, accrued expenses payable, and income tax payable

A typical business pays many expenses after the period in which the expenses are recorded. Following are common examples:

- A business hires a law firm that does a lot of legal work during the year, but the company doesn’t pay the bill until the following year.

- A business matches retirement contributions made by its employees but doesn’t pay its share of the latest payroll until the following year.

- A business has unpaid bills for telephone service, gas, electricity, and water that it used during the year.

Accountants use three types of liability accounts to record a business’s unpaid expenses:

- Accounts payable: This account is used for items that the business buys on credit and for which it receives an invoice (a bill) either in hard copy or over the Internet. For example, your business receives an invoice from its lawyers for legal work done. As soon as you receive the invoice, you record in the accounts payable liability account the amount that you owe. Later, when you pay the invoice, you subtract that amount from the accounts payable account, and your cash goes down by the same amount.

Accrued expenses payable: A business has to make estimates for several unpaid costs at the end of the year because it hasn’t received invoices or other types of bills for them. Examples of accrued expenses include the following:

- Unused vacation and sick days that employees carry over to the following year, which the business has to pay for in the coming year

- Unpaid bonuses to salespeople

- The cost of future repairs and part replacements on products that customers have bought and haven’t yet returned for repair

- The daily accumulation of interest on borrowed money that won’t be paid until the end of the loan period

Without invoices to reference, you have to examine your business operations carefully to determine which liabilities of this sort to record.

Income tax payable: This account is used for income taxes that a business still owes to the IRS at the end of the year. The income tax expense for the year is the total amount based on the taxable income for the entire year. Your business may not pay 100 percent of its income tax expense during the year; it may owe a small fraction to the IRS at year’s end. You record the unpaid amount in the income tax payable account.

Note: A business may be organized legally as a pass-through tax entity for income tax purposes, which means that it doesn’t pay income tax itself but instead passes its taxable income on to its owners. Chapter 4 explains these types of business entities. The business I refer to here is an ordinary corporation that pays income tax.

Reporting Unusual Gains and Losses

I have a small confession to make: The income statement examples in Figures 5-1, 5-2, and 5-3 are sanitized versions when compared with actual income statements in external financial reports. Suppose you took the trouble to read 100 income statements. You’d be surprised at the wide range of things you’d find in these statements. But I do know one thing for certain you’d discover.

Many businesses report unusual gains and losses in addition to their usual revenue and expenses. Remember that recording a gain increases an asset or decreases a liability. And recording a loss decreases an asset or increases a liability. The road to profit is anything but smooth and straight. Every business experiences an occasional gain or loss that’s off the beaten path — a serious disruption that comes out of the blue, doesn’t happen regularly, and impacts the bottom-line profit. Such unusual gains and losses are perturbations in the continuity of the business’s regular flow of profit-making activities.

Here are some examples of unusual gains and losses:

- Downsizing and restructuring the business: Layoffs require severance pay or trigger early retirement costs. Major segments of the business may be disposed of, causing large losses.

- Abandoning product lines: When you decide to discontinue selling a line of products, you lose at least some of the money that you paid for obtaining or manufacturing the products, either because you sell the products for less than you paid or because you just dump the products you can’t sell.

- Settling lawsuits and other legal actions: Damages and fines that you pay — as well as awards that you receive in a favorable ruling — are obviously nonrecurring losses or gains (unless you’re in the habit of being taken to court every year).

- Writing down (also called writing off) damaged and impaired assets: If products become damaged and unsellable or if fixed assets need to be replaced unexpectedly, you need to remove these items from the assets accounts. Even when certain assets are in good physical condition, if they lose their ability to generate future sales or other benefits to the business, accounting rules say that the assets have to be taken off the books or at least written down to lower book values.

- Changing accounting methods: A business may decide to use a different method for recording revenue and expenses than it did in the past, in some cases because the accounting rules (set by the authoritative accounting governing bodies — see Chapter 2) have changed. Often, the new method requires a business to record a one-time cumulative effect caused by the switch in accounting method. These special items can be huge.

- Correcting errors from previous financial reports: If you or your accountant discovers that a past financial report had a serious accounting error, you make a catch-up correction entry, which means that you record a loss or gain that has nothing to do with your performance this year.

The basic tests for an unusual gain or loss are that it is unusual in nature or infrequently occurring. Deciding what qualifies as an unusual gain or loss is not a cut-and-dried process. Different accountants may have different interpretations of what fits the concept of an unusual gain or loss.

According to financial reporting standards, a business should disclose unusual gains and losses on a separate line in the income statement or, alternatively, explain them in a footnote to its financial statements. I explain the role of footnotes in Chapter 9. There seems to be a general preference to put an unusual gain or loss on a separate line in the income statement. Therefore, in addition to the usual lines for revenue and expenses, the income statement would disclose separate lines for these out-of-the-ordinary happenings.

- Discontinuities become continuities: This business makes an extraordinary loss or gain a regular feature on its income statement. Every year or so, the business loses a major lawsuit, abandons product lines, or restructures itself. It reports certain “nonrecurring” gains or losses on a recurring basis.

- A discontinuity is used as an opportunity to record all sorts of write-downs and losses: When recording an unusual loss (such as settling a lawsuit), the business opts to record other losses at the same time, and everything but the kitchen sink (and sometimes that, too) gets written off. This so-called big-bath strategy says that you may as well take a big bath now in order to avoid taking little showers in the future.

A business may just have bad (or good) luck regarding unusual events that its managers couldn’t have predicted. If a business is facing a major, unavoidable expense this year, cleaning out all its expenses in the same year so it can start off fresh next year can be a clever, legitimate accounting tactic. But where do you draw the line between these accounting manipulations and fraud? All I can advise you to do is stay alert to these potential problems.

Watching for Misconceptions and Misleading Reports

One broad misconception about profit is that the numbers reported in the income statement are precise and accurate and can be relied on down to the last dollar. Call this the exactitude misconception. Virtually every dollar amount you see in an income statement probably would have been different if a different accountant had been in charge. I don’t mean that some accountants are dishonest and deceitful. It’s just that business transactions can get very complex and require forecasts and estimates. Different accountants would arrive at different interpretations of the “facts” and therefore record different amounts of revenue and expenses. Hopefully, the accountant is consistent over time so that year-to-year comparisons are valid.

Another serious misconception is that if profit is good, the financial condition of the business is good. As I write this sentence, the profit of Apple is very good. But I didn’t automatically assume that its financial condition was equally good. I looked in Apple’s balance sheet and found that its financial condition is very good indeed. (It has more cash and marketable investments on hand than the economy of many countries.) My point is that its bottom line doesn’t tell you anything about the financial condition of the business. You find this in the balance sheet, which I explain in Chapter 6.

The income statement occupies center stage; the bright spotlight is on this financial statement because it reports profit or loss for the period. But remember that a business reports three primary financial statements — the other two being the balance sheet and the statement of cash flows, which I discuss in the next two chapters. The three statements are like a three-ring circus. The income statement may draw the most attention, but you have to watch what’s going on in all three places. As important as profit is to the financial success of a business, the income statement is not an island unto itself.

I don’t like closing this chapter on a sour note, but I must point out that an income statement you read and rely on — as a business manager, an investor, or a lender — may not be true and accurate. In most cases (I’ll even say in the large majority of cases), businesses prepare their financial statements in good faith, and their profit accounting is honest. They may bend the rules a little, but basically their accounting methods are within the boundaries of GAAP even though the business puts a favorable spin on its profit number.

I wish I could say that financial reporting fraud doesn’t happen very often, but the number of high-profile accounting fraud cases over the recent two decades (and longer in fact) has been truly alarming. The CPA auditors of these companies didn’t catch the accounting fraud, even though this is one purpose of an audit. Investors who relied on the fraudulent income statements ended up suffering large losses.

Anytime I read a financial report, I keep in mind the risk that the financial statements may be “stage managed” to some extent — to make year-to-year reported profit look a little smoother and less erratic and to make the financial condition of the business appear a little better. Regrettably, financial statements don’t always tell it as it is. Rather, the chief executive and chief accountant of the business fiddle with the financial statements to some extent. I say much more about this tweaking of a business’s financial statements in later chapters.

Notice in

Notice in  The standard practice for almost all businesses is to report two-year comparative financial statements in side-by-side columns — for the period just ended and for the same period one year ago. Indeed, some companies present three-year comparative financial statements. Two-year or three-year financial statements may be legally required, such as for public companies whose debt and ownership shares are traded in a public market. I have to confess that the income statement in

The standard practice for almost all businesses is to report two-year comparative financial statements in side-by-side columns — for the period just ended and for the same period one year ago. Indeed, some companies present three-year comparative financial statements. Two-year or three-year financial statements may be legally required, such as for public companies whose debt and ownership shares are traded in a public market. I have to confess that the income statement in  Suppose a business records $100,000 depreciation for the period. You’d think that the depreciation expense account would be increased $100,000 and one or more fixed asset accounts would be decreased $100,000. Well, not so fast. Instead of directly decreasing the fixed asset account, the bookkeeper increases a contra asset account called accumulated depreciation. The balance in this negative account is deducted from the balance of the fixed asset account. In this manner, the original acquisition cost of the fixed asset is preserved, and the historical cost is reported in the balance sheet. I discuss this practice in

Suppose a business records $100,000 depreciation for the period. You’d think that the depreciation expense account would be increased $100,000 and one or more fixed asset accounts would be decreased $100,000. Well, not so fast. Instead of directly decreasing the fixed asset account, the bookkeeper increases a contra asset account called accumulated depreciation. The balance in this negative account is deducted from the balance of the fixed asset account. In this manner, the original acquisition cost of the fixed asset is preserved, and the historical cost is reported in the balance sheet. I discuss this practice in  Every company that stays in business for more than a couple of years experiences an unusual gain or loss of one sort or another. But beware of a business that takes advantage of these discontinuities in the following ways:

Every company that stays in business for more than a couple of years experiences an unusual gain or loss of one sort or another. But beware of a business that takes advantage of these discontinuities in the following ways: