Chapter 2

Introducing Financial Statements

IN THIS CHAPTER

Identifying the information components in financial statements

Evaluating profit performance and financial condition

Knowing the limits of financial statements

Recognizing the sources of accounting standards

Chapter 1 presents a brief introduction to the three primary business financial statements: the income statement, the balance sheet, and the statement of cash flows. In this chapter, you get more interesting tidbits about these three financials, as they’re sometimes called. Then, in Part 2, you really get the goods. Remember when you were learning to ride a bicycle? Chapter 1 is like getting on the bike and learning to keep your balance. In this chapter, you put on your training wheels and start riding. Then, when you’re ready, the chapters in Part 2 explain all 21 gears of the financial statements bicycle, and then some.

For each financial statement, I introduce its basic information components. The purpose of financial statements is to communicate information that is useful to the readers of the financial statements, to those who are entitled to the information. Financial statement readers include the managers of the business and its lenders and investors. These constitute the primary audience for financial statements. (Beyond this primary audience, others are also interested in a business’s financial statements, such as its labor union or someone considering buying the business.) Think of yourself as a shareholder in a business. What sort of information would you want to know about the business? The answer to this question should be the touchstone for the accountant in preparing the financial statements.

The financial statements explained in this chapter are for businesses. Business financial statements serve as a useful template for not-for-profit (NFP) entities and other organizations (social clubs, homeowners’ associations, retirement communities, and so on). In short, business financial statements are a good reference point for the financial statements of non-business entities. There are differences but not as many as you may think. As I go along in this and the following chapters, I point out the differences between business and non-business financial statements.

Toward the end of this chapter, I briefly discuss accounting standards and financial reporting standards. Notice here that I distinguish accounting from financial reporting. Accounting standards deal primarily with how to record transactions for measuring profit and for putting values on assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity. Financial reporting standards focus on additional aspects such as the structure and presentation of financial statements, disclosure in the financial statements and elsewhere in the report, and other matters. I use the term financial accounting to include both types of standards.

Setting the Stage for Financial Statements

This chapter focuses on the basic information components of each financial statement reported by a business. The first step is to get a good idea of the information content reported in financial statements. The second step is to become familiar with more details about the “architecture,” rules of classification, and other features of financial statements, which I explain in Part 2 of the book.

Offering a few preliminary comments about financial statements

Realistic examples are needed to illustrate and explain financial statements. But this presents a slight problem. The information content of a business’s financial statements depends on whether it sells products or services, invests in other businesses, and so on. For example, the financial statements of a movie theater chain are different from those of a bank, which are different from those of an airline, which are different from an automobile manufacturer’s, which are different from — well, you name it.

The classic example used to illustrate financial statements involves a business that sells products and sells on credit to its customers. Therefore, the assets in the example include receivables from the business’s sales on credit and inventory of products it has purchased or manufactured that are awaiting future sale. Keep in mind, however, that many businesses that sell products do not sell on credit to their customers. Many retail businesses sell only for cash (or accept credit or debit cards that are near cash). Such businesses do not have a receivables asset.

The illustrative financial statements that follow in this part and Part 2 do not include a historical narrative of the business. Nevertheless, whenever you see financial statements, I encourage you to think about the history of the business. To help you out in this regard, here are some particulars about the business example I use in this chapter:

- It sells products to other businesses (not on the retail level).

- It sells on credit, and its customers take a month or so before they pay.

- It holds a fairly large stock of products awaiting sale.

- It owns a wide variety of long-term operating assets that have useful lives from 3 to 30 years or longer (building, machines, tools, computers, office furniture, and so on).

- It has been in business for many years and has made a profit most years.

- It borrows money for part of the total assets it needs.

- It’s organized as a corporation and pays federal and state income taxes on its annual taxable income.

- It has never been in bankruptcy and is not facing any immediate financial difficulties.

The following sections present the company’s annual income statement for the year just ended, its balance sheet at the end of the year, and its statement of cash flows for the year.

Looking at other aspects of reporting financial statements

The financial statements you see in this chapter are more in the nature of an outline. Actual financial statements use only one- or two-word account titles on the assumption that you know what all these labels mean. What you see in this chapter, on the other hand, are the basic information components of each financial statement. I explain the full-blown, classified, detailed financial statements in Part 2 of the book. (I know you’re anxious to get to those chapters.) In this chapter, I offer descriptions for each financial statement element rather than the terse and technical account titles you find in actual financial statements. Also, I strip out subtotals that you see in actual financial statements because they aren’t necessary at this point. So, with all these caveats in mind, let’s get going.

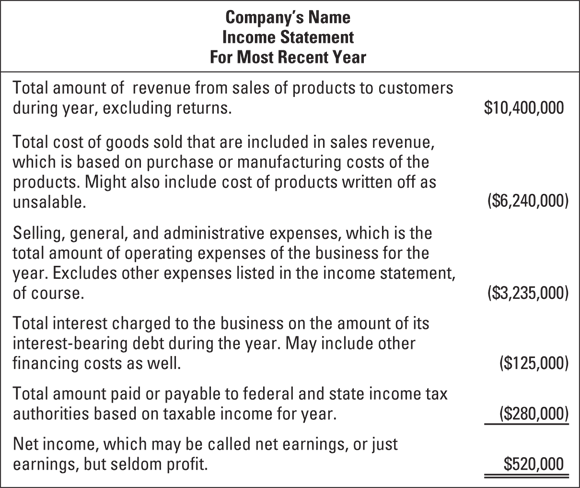

Income Statement

First on the minds of financial report readers is the profit performance of the business. The income statement is the all-important financial statement that summarizes the profit-making activities of a business over a period of time. Figure 2-1 shows the basic information content of an external income statement for our company example. External means that the financial statement is released outside the business to those entitled to receive it — primarily its shareowners and lenders. Internal financial statements stay within the business and are used mainly by its managers; they aren’t circulated outside the business because they contain competitive and confidential information.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 2-1: Income statement information components for a business that sells products.

Presenting the components of the income statement

Figure 2-1 presents the major ingredients, or information packets, in the income statement for a company that sells products. As you may expect, the income statement starts with sales revenue on the top line. There’s no argument about this, although in the past, certain companies didn’t want to disclose their annual sales revenue (to hide the large percent of profit they were earning on sales revenue).

Sales revenue is the total amount that has been or will be received from the company’s customers for the sales of products to them. Simple enough, right? Well, not really. The accounting profession is currently reexamining the technical accounting standards for recording sales revenue, and this has proven to be a challenging task. Our business example, like most businesses, has adopted a certain set of procedures for the timeline of recording its sales revenue.

Recording expenses involves much more troublesome accounting problems than revenue problems for most businesses. Also, there’s the fundamental question regarding which information to disclose about expenses and which information to bury in larger expense categories in the external income statement. I say much more about expenses in later chapters. At this point, direct your attention to the four kinds of expenses in Figure 2-1. Expenses are deducted from sales revenue to determine the final profit for the period, which is referred to as the bottom line. Actually, the preferred label is net income, as you see in the figure.

Only one conglomerate operating expense has to be disclosed. In Figure 2-1, it’s called selling, general, and administrative expenses, which is a popular title in income statements. This is an all-inclusive expense total that mixes together many kinds of expenses, including labor costs, utility costs, depreciation of assets, and so on. But it doesn’t include interest expenses or income tax expense; these two expenses are always reported separately in an income statement.

The cost of goods sold expense and the selling, general, and administrative expenses take the biggest bites out of sales revenue. The other two expenses (interest and income tax) are relatively small as a percent of annual sales revenue but are important enough in their own right to be reported separately. And though you may not need this reminder, bottom-line profit (net income) is the amount of sales revenue in excess of the business’s total expenses. If either sales revenue or any of the expense amounts are wrong, then profit is wrong. (I harp on this point throughout the book.)

Income statement pointers

Inside most businesses, a profit statement is called a P&L (profit and loss) report. These internal profit performance reports to the managers of a business include more detailed information about expenses and about sales revenue — a good deal more! Reporting just four expenses to managers (as shown in Figure 2-1) would not do. Chapter 11 explains P&L reports to managers.

Sales revenue refers to sales of products or services to customers. In some income statements, you also see the term income, which generally refers to amounts earned by a business from sources other than sales. For example, a real estate rental business receives rental income from its tenants. (In the example in this chapter, the business has only sales revenue.)

The income statement gets the most attention from business managers, lenders, and investors (not that they ignore the other two financial statements). The much-abbreviated versions of income statements that you see in the financial press, such as in The Wall Street Journal, report the top line (sales revenue and income) and the bottom line (net income) and not much more. Refer to Chapter 5 for more information on income statements.

Balance Sheet

A more accurate name for a balance sheet is statement of financial condition or statement of financial position, but the term balance sheet has caught on, and most people use this term. Keep in mind that the most important thing is not the “balance” but rather the information reported in this financial statement.

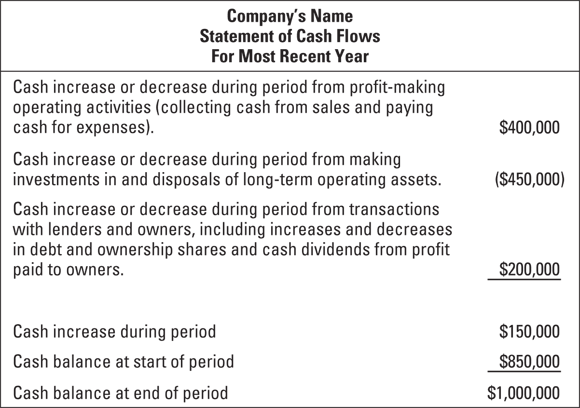

In brief, a balance sheet summarizes on the one hand the assets of the business and on the other hand the sources of the assets. However, looking at assets is only half the picture. The other half consists of the liabilities and owner equity of the business. Cash is listed first, and other assets are listed in the order of their nearness to cash. Liabilities are listed in order of their due dates (the earliest first, and so on). Liabilities are listed ahead of owners’ equity. I discuss the ordering of the components in a balance sheet in Chapter 6.

Presenting the components of the balance sheet

Figure 2-2 shows the building blocks of a typical balance sheet for a business that sells products on credit. As mentioned, one reason the balance sheet is called by this name is that its two sides balance, or are equal in total amounts. In this example, the $5.2 million total assets equals the $5.2 million total liabilities and owners’ equity. The balance or equality of total assets on the one side of the scale and the sum of liabilities plus owners’ equity on the other side of the scale is expressed in the accounting equation, which I discuss in Chapter 1. Note: The balance sheet in Figure 2-2 shows the essential elements in this financial statement. In a financial report, the balance sheet includes additional features and frills, which I explain in Chapter 6.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 2-2: Balance sheet information components for a business that sells products and makes sales on credit.

Take a quick walk through the balance sheet. For a company that sells products on credit, assets are reported in the following order: First is cash, then receivables, then cost of products held for sale, and finally the long-term operating assets of the business. Moving to the other side of the balance sheet, the liabilities section starts with the trade liabilities (from buying on credit) and liabilities for unpaid expenses. Following these operating liabilities is the interest-bearing debt of the business. Owners’ equity sources are then reported below liabilities. So a balance sheet is a composite of assets on one hand and a composite of liabilities and owners’ equity sources on the other hand.

A company that sells services doesn’t has an inventory of products being held for sale. A service company may or may not sell on credit. Airlines don’t sell on credit, for example. If a service business doesn’t sell on credit, it won’t have two of the sizable assets you see in Figure 2-2: receivables from credit sales and inventory of products held for sale. Generally, this means that a service-based business doesn’t need as much total assets compared with a products-based business with the same size sales revenue.

The smaller amount of total assets of a service business means that the other side of its balance sheet is correspondingly smaller. In plain terms, this means that a service company doesn’t need to borrow as much money or raise as much capital from its equity owners.

As you may suspect, the particular assets reported in the balance sheet depend on which assets the business owns. I include just four basic types of assets in Figure 2-2. These are the hardcore assets that a business selling products on credit would have. It’s possible that such a business could lease (or rent) virtually all its long-term operating assets instead of owning them, in which case the business would report no such assets. In this example, the business owns these so-called fixed assets. They’re fixed because they are held for use in the operations of the business and are not for sale, and their usefulness lasts several years or longer.

Balance sheet pointers

So, where does a business get the money to buy its assets? Most businesses borrow money on the basis of interest-bearing notes or other credit instruments for part of the total capital they need for their assets. Also, businesses buy many things on credit and, at the balance sheet date, owe money to their suppliers, which will be paid in the future.

These operating liabilities are never grouped with interest-bearing debt in the balance sheet. The accountant would be tied to the stake for doing such a thing. Liabilities are not intermingled with assets — this is a definite no-no in financial reporting. You can’t subtract certain liabilities from certain assets and report only the net balance.

Could a business’s total liabilities be greater than its total assets? Well, not likely — unless the business has been losing money hand over fist. In the vast majority of cases, a business has more total assets than total liabilities. Why? For two reasons:

- Its owners have invested money in the business.

- The business has earned profit over the years, and some (or all) of the profit has been retained in the business. Making profit increases assets; if not all the profit is distributed to owners, the company’s assets rise by the amount of profit retained.

The profit for the most recent period is found in the income statement; periodic profit is not reported in the balance sheet. The profit reported in the income statement is before any distributions from profit to owners. The cumulative amount of profit over the years that hasn’t been distributed to the business’s owners is reported in the owners’ equity section of the company’s balance sheet.

By the way, notice that the balance sheet in Figure 2-2 is presented in a top-and-bottom format instead of a left-and-right format. Either the vertical (portrait) or horizontal (landscape) mode of display is acceptable. You see both layouts in financial reports. Of course, the two sides of the balance sheet should be kept together, either on one page or on facing pages in the financial report. You can’t put assets up front and hide the other side of the balance sheet in the rear of the financial report.

Statement of Cash Flows

To survive and thrive, business managers confront three financial imperatives:

- Make an adequate profit (or at least break even, for a not-for-profit entity). The income statement reports whether the business made a profit or suffered a loss for the period.

- Keep the financial condition in good shape. The balance sheet reports the financial condition of the business at the end of the period.

- Control cash flows. Management’s control over cash flows is reported in the statement of cash flows, which presents a summary of the business’s sources and uses of cash during the same period as the income statement.

This section introduces you to the statement of cash flows. (My son, Tage, and I coauthored Cash Flow For Dummies, which you may want to take a peek at for more information.) Financial reporting standards require that the statement of cash flows be reported when a business reports an income statement.

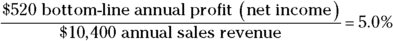

Presenting the components of the statement of cash flows

Successful business managers tell you that they have to manage both profit and cash flow; you can’t do one and ignore the other. Business managers have to deal with a two-headed dragon in this respect. Ignoring cash flow can pull the rug out from under a successful profit formula.

- The first reconciles net income for the period with the cash flow from the business’s profit-making activities, or operating activities.

- The second summarizes the company’s investing transactions during the period.

- The third reports the company’s financing transactions.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 2-3: Information components of the statement of cash flows.

The net increase or decrease in cash from the three types of cash activities during the period is added to or subtracted from the beginning cash balance to get the cash balance at the end of the year.

In the example, the business earned $520,000 profit (net income) during the year (see Figure 2-1). The cash result of its operating activities was to increase its cash by $400,000, which you see in the first part of the statement of cash flows (Figure 2-3). This still leaves $120,000 of profit to explain. This doesn’t mean that the profit number is wrong. The actual cash inflows from revenues and outflows for expenses run on a different timetable from when the sales revenue and expenses are recorded for determining profit. I give a more comprehensive explanation of the differences between cash flows and sales revenue and expenses in Chapter 7.

The second part of the statement of cash flows sums up the long-term investments the business made during the year, such as constructing a new production plant or replacing machinery and equipment. If the business sold any of its long-term assets, it reports the cash inflows from these divestments in this section of the statement of cash flows. The cash flows of other investment activities (if any) are reported in this part of the statement as well. As you can see in Figure 2-3, the business invested $450,000 in new long-term operating assets (trucks, equipment, tools, and computers).

The third part of the statement sums up the dealings between the business and its sources of capital during the period — borrowing money from lenders and raising capital from its owners. Cash outflows to pay debt are reported in this section, as are cash distributions from profit paid to the owners of the business. The third part of the example statement shows that the result of these transactions was to increase cash by $200,000. (By the way, in this example, the business didn’t make cash distributions from profit to its owners. It probably could have, but it didn’t — which is an important point that I discuss later in “Why no cash distribution from profit?”)

As you see in Figure 2-3, the net result of the three types of cash activities was a $150,000 increase during the year. The increase is added to the cash balance at the start of the year to get the cash balance at the end of the year, which is $1.0 million. I should make one point clear: The $150,000 cash increase during the year (in this example) is never referred to as a cash flow bottom line or any such thing.

Statement of cash flows pointers

When I started in public accounting, the cash flow statement wasn’t required in financial reports. In 1987, the American rulemaking body for financial accounting standards (the Financial Accounting Standards Board) made it a required statement. Relatively speaking, this financial statement hasn’t been around that long — only about 30 years at the time of this writing. How has it gone? Well, in my humble opinion, this financial statement is a disaster for financial report readers.

Statements of cash flows of most businesses are frustratingly difficult to read and far too technical. The average financial report reader understands the income statement and balance sheet. Certain items may be hard to fathom, but overall, the reader can make sense of the information in the two financial statements. In contrast, trying to follow the information in a statement of cash flows — especially the first section of the statement — can be a challenge even for a CPA. (More about this issue in Chapter 7.)

A Note about the Statement of Changes in Shareowners’ Equity

Many business financial reports include a fourth financial statement — or at least it’s called a “statement.” It’s really a summary of the changes in the constituent elements of owners’ equity (stockholders’ equity of a corporation). The corporation is one basic type of legal structure that businesses use. In Chapter 4, I explain the alternative legal structures available for conducting business operations. I don’t show a statement of changes in owners’ equity here. I show an example in Chapter 9, in which I explain the preparation of a financial report for release.

When a business has a complex owner’s equity structure, a separate summary of changes in the components of owners’ equity during the period is useful for the owners, the board of directors, and the top-level managers. On the other hand, in some cases, the only changes in owners’ equity during the period were earning profit and distributing part of the cash flow from profit to owners. In this situation, there isn’t much need for a summary of changes in owners’ equity. The financial statement reader can easily find profit in the income statement and cash distributions from profit (if any) in the statement of cash flows. For details, see the later section “Why no cash distribution from profit?”

Gleaning Important Information from Financial Statements

The whole point of reporting financial statements is to provide important information to people who have a financial interest in the business — mainly its investors and lenders. From that information, investors and lenders are able to answer key questions about the financial performance and condition of the business. I discuss a few of these key questions in this section. In Chapters 10 and 16, I discuss a longer list of questions and explain financial statement analysis.

How’s profit performance?

Investors use two important measures to judge a company’s annual profit performance. Here, I use the data from Figures 2-1 and 2-2 for the product company. Of course, you can do the same ratio calculations for a service business. For convenience, the dollar amounts here are expressed in thousands:

- Return on sales = profit as a percent of annual sales revenue:

- Return on equity = profit as a percent of owners’ equity:

Profit looks pretty thin compared with annual sales revenue. The company earns only 5 percent return on sales. In other words, 95 cents out of every sales dollar goes for expenses, and the company keeps only 5 cents for profit. (Many businesses earn 10 percent or higher return on sales.) However, when profit is compared with owners’ equity, things look a lot better. The business earns more than 21 percent profit on its owners’ equity. I’d bet you don’t have many investments earning 21 percent per year.

Is there enough cash?

Cash is the lubricant of business activity. Realistically, a business can’t operate with a zero cash balance. It can’t wait to open the morning mail to see how much cash it will have for the day’s needs (although some businesses try to operate on a shoestring cash balance). A business should keep enough cash on hand to keep things running smoothly even when there are interruptions in the normal inflows of cash. A business has to meet its payroll on time, for example. Keeping an adequate balance in the checking account serves as a buffer against unforeseen disruptions in normal cash inflows.

At the end of the year, the company in our example has $1 million cash on hand (refer to Figure 2-2). This cash balance is available for general business purposes. (If there are restrictions on how the business can use its cash balance, the business is obligated to disclose the restrictions.) Is $1 million enough? Interestingly, businesses do not have to comment on their cash balance. I’ve never seen such a comment in a financial report.

The business has $650,000 in operating liabilities that will come due for payment over the next month or so (see Figure 2-2). Therefore, it has enough cash to pay these liabilities. But it doesn’t have enough cash on hand to pay its operating liabilities and its $2.08 million interest-bearing debt. Lenders don’t expect a business to keep a cash balance more than the amount of debt; this condition would defeat the very purpose of lending money to the business, which is to have the business put the money to good use and be able to pay interest on the debt.

Lenders are more interested in the ability of the business to control its cash flows so that when the time comes to pay off loans, it will be able to do so. They know that the other, non-cash assets of the business will be converted into cash flow. Receivables will be collected, and products held in inventory will be sold, and the sales will generate cash flow. So you shouldn’t focus just on cash; you should look at the other assets as well.

Taking this broader approach, the business has $1 million cash, $800,000 receivables, and $1.56 million inventory, which adds up to $3.36 million in cash and cash potential. Relative to its $2.73 million total liabilities ($650,000 operating liabilities plus $2.08 million debt), the business looks like it’s in pretty good shape. On the other hand, if it turns out that the business isn’t able to collect its receivables and isn’t able to sell its products, the business would end up in deep doo-doo.

The business’s cash balance equals a little more than one month of sales activity, which most lenders and investors would consider adequate.

Can you trust financial statement numbers?

Whether the financial statements are correct depends on the answers to two basic questions:

- Does the business have a reliable accounting system in place and employ competent accountants?

- Have its managers manipulated the business’s accounting methods or deliberately falsified the numbers?

Furthermore, there are a lot of crooks and dishonest persons in the business world who think nothing of manipulating the accounting numbers and cooking the books. Also, organized crime is involved in many businesses. And I have to tell you that in my experience, many businesses don’t put much effort into keeping their accounting systems up to speed, and they skimp on hiring competent accountants. In short, there’s a risk that the financial statements of a business could be incorrect and seriously misleading.

To increase the credibility of their financial statements, many businesses hire independent CPA auditors to examine their accounting systems and records and to express opinions on whether the financial statements conform to established standards. In fact, some business lenders insist on an annual audit by an independent CPA firm as a condition of making a loan. The outside, nonmanagement investors in a privately owned business could vote to have annual CPA audits of the financial statements. Public companies have no choice; under federal securities laws, a public company is required to have annual audits by an independent CPA firm.

Why no cash distribution from profit?

Distributions from profit by a business corporation are called dividends (because the total amount distributed is divided up among the stockholders). Cash distributions from profit to owners are included in the third section of the statement of cash flows (refer to Figure 2-3). But in our example, the business didn’t make any cash distributions from profit — even though it earned $520,000 net income (see Figure 2-1). Why not?

The business realized $400,000 cash flow from its profit-making (operating) activities (see Figure 2-3). In most cases, this would be the upper limit on how much cash a business would distribute from profit to its owners. Should the business have distributed, say, at least half of its cash flow from profit, or $200,000, to its owners? If you owned 20 percent of the ownership shares of the business, you would have received 20 percent, or $40,000, of the distribution. But you got no cash return on your investment in the business. Your shares should be worth more because the profit for the year increased the company’s owners’ equity, but you didn’t see any of this increase in your wallet.

Keeping in Compliance with Accounting and Financial Reporting Standards

When an independent CPA audits the financial report of a business, there’s no doubt regarding which accounting and financial reporting standards the business uses to prepare its financial statements and other disclosures. The CPA explicitly states which standards are being used in the auditor’s report. What about unaudited financial reports? Well, the business could clarify which accounting and financial reporting standards it uses, but you don’t see such disclosure in all cases.

When the financial report of a business is not audited and does not make clear which standards are being used to prepare its financial report, the reader is entitled to assume that appropriate standards are being used. However, a business may be way out in left field (or out of the ballpark) in the “guideposts” it uses for recording profit and in the preparation of its financial statements. A business may make up its own “rules” for measuring profit and preparing financial statements. In this book, I concentrate on authoritative standards, of course.

Imagine the confusion that would result if every business were permitted to invent its own accounting methods for measuring profit and for putting values on assets and liabilities. What if every business adopted its own individual accounting terminology and followed its own style for presenting financial statements? Such a state of affairs would be a Tower of Babel.

The goal is to establish broad-scale uniformity in accounting methods for all businesses. The idea is to make sure that all accountants are singing the same tune from the same hymnal. The authoritative bodies write the tunes that accountants have to sing.

Looking at who makes the standards

Who are the authoritative bodies that set the standards for financial accounting and reporting? In the United States, the highest-ranking authority in the private (nongovernment) sector for making pronouncements on accounting and financial reporting standards — and for keeping these standards up-to-date — is the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). This rulemaking body has developed a codification of all its pronouncements. This is where accountants look to first.

Outside the United States, the main authoritative accounting-standards setter is the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), which is based in London. The IASB was founded in 2001. More than 7,000 public companies have their securities listed on the several stock exchanges in the European Union (EU) countries. In many regards, the IASB operates in a manner similar to the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in the United States, and the two have very similar missions. The IASB has already issued many standards, which are called International Financial Reporting Standards. Without going into details, FASB and IASB are not in perfect harmony (even though congruence of their standards was the original goal of the two organizations).

Also, in the U.S., the federal Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has broad powers over accounting and financial reporting standards for companies whose securities (stocks and bonds) are publicly traded. Actually, because it derives its authority from federal securities laws that govern the public issuance and trading in securities, the SEC outranks the FASB. The SEC has on occasion overridden the FASB but not very often.

Knowing about GAAP

The authoritative standards and rules that govern financial accounting and reporting by businesses in the United States are called generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). The financial statements of an American business should be in full compliance with GAAP regarding reporting its cash flows, profit-making activities, and financial condition — unless the business makes very clear that it has prepared its financial statements using some other basis of accounting or has deviated from GAAP in one or more significant respects.

There are upwards of 10,000 public companies in the United States and easily more than a million privately owned businesses. Now, am I telling you that all these businesses should use the same accounting methods, terminology, and presentation styles for their financial statements? Putting it in such a stark manner makes me suck in my breath a little. The ideal answer is that all businesses should use the same rulebook of GAAP. However, the rulebook permits alternative accounting methods for some transactions. Furthermore, accountants have to interpret the rules as they apply GAAP in actual situations. The devil is in the detail.

In the United States, GAAP constitute the gold standard for preparing financial statements of business entities. The presumption is that any deviations from GAAP would cause misleading financial statements. If a business honestly thinks it should deviate from GAAP — in order to better reflect the economic reality of its transactions or situation — it should make very clear that it has not complied with GAAP in one or more respects. If deviations from GAAP are not disclosed, the business may have legal exposure to those who relied on the information in its financial report and suffered a loss attributable to the misleading nature of the information.

GAAP also include requirements for disclosure, which refers to the following:

- The types of information that have to be included with the financial statements

- How information is classified and presented in financial statements (mainly in the form of footnotes)

The SEC makes the disclosure rules for public companies. Disclosure rules for private companies are controlled by GAAP. Chapter 9 explains the disclosures that are required in addition to the three primary financial statements of a business (the income statement, balance sheet, and statement of cash flows).

Divorcing public and private companies

Traditionally, GAAP and financial reporting standards were viewed as equally applicable to public companies (generally large corporations) and private companies (generally smaller). For some time, private companies have argued that some of the standards issued by the FASB are too complex and burdensome for private companies to apply. Although most accountants don’t like to admit it, there’s always been a de facto divergence in actual financial reporting practices by private companies compared with the more rigorously enforced standards for public companies. For example, a surprising number of private companies still do not include a statement of cash flows in their financial reports, even though this has been a GAAP requirement for 30 years.

Private companies do not have many of the accounting problems of large, public companies. For example, many public companies deal in complex derivative instruments, issue stock options to managers, provide highly developed defined-benefit retirement and health benefit plans for their employees, enter into complicated intercompany investment and joint venture operations, have complex organizational structures, and so on. Most private companies don’t have to deal with these issues.

Finally, I should mention in passing that the AICPA, the national association of CPAs, has started a project to develop an Other Comprehensive Basis of Accounting for privately held small and medium-sized entities. Oh my! What a time we live in regarding accounting standards. The upshot seems to be that we’re drifting toward separate accounting standards for larger public companies versus smaller private companies — and maybe even a third branch of standards for small and medium-sized companies.

Following the rules and bending the rules

An often-repeated story concerns three persons interviewing for an important accounting position. They’re asked one key question: “What’s 2 plus 2?” The first candidate answers, “It’s 4,” and is told, “Don’t call us. We’ll call you.” The second candidate answers, “Well, most of the time the answer is 4, but sometimes it’s 3, and sometimes it’s 5.” The third candidate answers, “What do you want the answer to be?” Guess who gets the job. This story exaggerates, of course, but it does have an element of truth.

The point is that interpreting GAAP is not cut-and-dried. Many accounting standards leave a lot of wiggle room for interpretation. Guidelines would be a better word to describe many accounting rules. Deciding how to account for certain transactions and situations requires seasoned judgment and careful analysis of the rules. Furthermore, many estimates have to be made. (See the sidebar “Depending on estimates and assumptions.”) Deciding on accounting methods requires, above all else, good faith.

The philosophy behind the need for standards is that all businesses should follow uniform methods for measuring and reporting profit performance and reporting financial condition. Consistency in financial accounting across all businesses is the name of the game. I won’t bore you with a lengthy historical discourse on the development of accounting and financial reporting standards in the United States. The general consensus (backed by law) is that businesses should use consistent accounting methods and terminology. General Motors and Microsoft should use the same accounting methods; so should Wells Fargo and Apple. Of course, businesses in different industries have different types of transactions, but the same types of transactions should be accounted for in the same way. That is the goal.

The philosophy behind the need for standards is that all businesses should follow uniform methods for measuring and reporting profit performance and reporting financial condition. Consistency in financial accounting across all businesses is the name of the game. I won’t bore you with a lengthy historical discourse on the development of accounting and financial reporting standards in the United States. The general consensus (backed by law) is that businesses should use consistent accounting methods and terminology. General Motors and Microsoft should use the same accounting methods; so should Wells Fargo and Apple. Of course, businesses in different industries have different types of transactions, but the same types of transactions should be accounted for in the same way. That is the goal. The financial statements of a business do not present a “history” of the business. Financial statements are, to a large extent, limited to the recent profit performance and financial condition of the business. A business may add some historical discussion and charts that aren’t strictly required by financial reporting standards. (Public corporations that have their ownership shares and debt traded in open markets are subject to various disclosure requirements under federal law, including certain historical information.)

The financial statements of a business do not present a “history” of the business. Financial statements are, to a large extent, limited to the recent profit performance and financial condition of the business. A business may add some historical discussion and charts that aren’t strictly required by financial reporting standards. (Public corporations that have their ownership shares and debt traded in open markets are subject to various disclosure requirements under federal law, including certain historical information.) In the product company example (see

In the product company example (see