Chapter 10

Reading a Financial Report

IN THIS CHAPTER

Looking after your investments

Using ratios to interpret profit performance

Using ratios to interpret financial condition

Scanning footnotes and sorting out important ones

Checking out the auditor’s report

This chapter focuses on the external financial report that a business sends to its lenders and shareowners. Many of the topics and ratios explained in the chapter apply to not-for-profit (NFP) entities as well. But the main focus is reading the financial reports of profit-motivated business entities. External financial reports are designed for the non-manager stakeholders in the business. The business’s managers should definitely understand how to read and analyze its external financial statements, and managers should do additional financial analysis, which I discuss in Chapter 11. This additional financial analysis by managers uses confidential accounting information that is not circulated outside the business.

You could argue that this chapter goes beyond the domain of accounting. Yes, this chapter ventures into the field of financial statement analysis. Some argue that this is in the realm of finance and investments, not accounting. Well, my answer is this: I assume one of your reasons for reading this book is to understand and learn how to read financial statements. From this perspective, this chapter definitely should be included, whether or not the topics fit into a strict definition of accounting.

Some years ago, a private business needed additional capital to continue its growth. Its stockholders could not come up with all the additional capital the business needed. So they decided to solicit several people to invest money in the company, including me. (In Chapter 4, I explain corporations and the stock shares they issue when owners invest capital in the business.) I studied the business’s most recent financial report. I had an advantage that you can have, too, if you read this chapter: I know how to read a financial report and what to look for.

After studying the financial report, I concluded that the profit prospects of this business looked promising and that I probably would receive reasonable cash dividends on my investment. I also thought the business might be bought out by a bigger business someday, and I would make a capital gain. That proved to be correct: The business was bought out a few years later, and I doubled my money (plus I earned dividends along the way).

Not all investment stories have a happy ending, of course. As you know, stock share market prices go up and down. A business may go bankrupt, causing its lenders and shareowners large losses. This chapter isn’t about guiding you toward or away from making specific types of investments. My purpose is to explain basic ratios and other tools lenders and investors use for getting the most information value out of a business’s financial reports — to help you become a more intelligent lender and investor.

Knowing the Rules of the Game

When you invest money in a business venture or lend money to a business, you receive regular financial reports from the business. The primary premise of financial reporting is accountability — to inform the sources of a business’s ownership and debt capital about the financial performance and condition of the business. Abbreviated financial reports are sent to owners and lenders every three months. A full and comprehensive financial report is sent annually. The ratios and techniques of analysis I explain in the chapter are useful for both quarterly and annual financial reports.

There are written rules for financial reports, and there are unwritten rules. The written rules in the United States are called generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). The movement toward adopting international accounting standards isn’t dead, but it is on life support, so in this chapter, I assume that U.S. GAAP are used to prepare the financial statements.

The unwritten rules don’t have a name. For example, there’s no explicit rule prohibiting the use of swear words and vulgar expressions in financial reports. Yet, quite clearly, there is a strict unwritten rule against improper language in financial reports. There’s one unwritten rule in particular that you should understand: A financial report isn’t a confessional. A business doesn’t have to lay bare all its problems in its financial reports. A business doesn’t comment on all its difficulties in reporting its financial affairs to the outside world.

Making Investment Choices

An investment opportunity in a private business won’t show up on your doorstep every day. However, if you make it known that you have money to invest as an equity shareholder, you may be surprised at how many offers come your way. Alternatively, you can invest in publicly traded securities, those stocks and bonds traded every day in major securities markets. Your stockbroker would be delighted to execute a buy order for 100 shares of, say, Caterpillar for you. Keep in mind that your money doesn’t go to Caterpillar; the company isn’t raising additional money. Your money goes to the seller of the 100 shares. You’re investing in the secondary capital market — the trading in stocks by buyers and sellers after the shares were originally issued some time ago.

In contrast, I invested in the primary capital market, which means that my money went directly to the business. These days, a growing tactic of raising money is crowdfunding, which is done over the Internet. On a website, a new or early-stage business invites anyone with money to join in the venture and become a stockholder. Usually, you can invest a relatively small amount of money in a crowdfunding appeal. The business seeking the money is counting on a large number of people to invest money in the venture.

You may choose not to manage your securities investments yourself. Instead, you can put your money in any of the thousands of mutual funds available today, or in an exchange-traded fund (ETF), or in closed-end investment companies, or in unit investment trusts, and so on. You’ll have to read other books to gain an understanding of the choices you have for investing your money and managing your investments. Be very careful about books that promise spectacular investment results with no risk and little effort. One book that is practical, well-written, and levelheaded is Investing For Dummies, by Eric Tyson (Wiley).

Investors in securities of public businesses have many sources of information at their disposal. Of course, they can read the financial reports of the businesses they have invested in and those they’re thinking of investing in. Instead of thoroughly reading these financial reports, they may rely on stockbrokers, the financial press, and other sources of information. Many individual investors turn to their stockbrokers for investment advice. Brokerage firms put out all sorts of analyses and publications, and they participate in the placement of new stock and bond securities issued by public businesses. A broker will be glad to provide you with information from companies’ latest financial reports. So why should you bother reading this chapter if you can rely on other sources of investment information?

This chapter covers financial statement ratios that you should understand as well as signs to look for in audit reports. (Part 2 of this book explains the three primary financial statements that are the core of every financial report: the income statement, the balance sheet, and the statement of cash flows.) I also suggest how to sort through the footnotes that are an integral part of every financial report to identify those that have the most importance to you.

Contrasting Reading Financial Reports of Private Versus Public Businesses

Public businesses are saddled with the additional layer of requirements issued by the Securities and Exchange Commission. (This federal agency has no jurisdiction over private businesses.) The financial reports and other forms filed with the SEC are available to the public at www.sec.gov. The anchor of these forms is the annual 10-K, which includes the business’s financial statements in prescribed formats, with many supporting schedules and detailed disclosures that the SEC requires.

A typical annual financial report by a public company to its stockholders is a glossy booklet with excellent art and graphic design, including high-quality photographs. The company’s products are promoted, and its people are featured in glowing terms that describe teamwork, creativity, and innovation — I’m sure you get the picture. In contrast, the reports to the SEC look like legal briefs — there’s nothing fancy in these filings. The SEC filings contain information about certain expenses and require disclosure about the history of the business, its main markets and competitors, its principal officers, any major changes on the horizon, the major risks facing the business, and so on. Professional investors and investment managers definitely should read the SEC filings. By the way, if you want information on the compensation of the top-level officers of the business, you have to go to its proxy statement (see the sidebar “Studying the proxy statement”).

Using Ratios to Digest Financial Statements

Financial statements have lots of numbers in them. (Duh!) All these numbers can seem overwhelming when you’re trying to see the big picture and make general conclusions about the financial performance and condition of the business. Instead of actually reading your way through the financial statements — that is, carefully reading every line reported in all the financial statements — one alternative is to compute certain ratios to extract the main messages from the financial statements. Many financial report readers go directly to ratios and don’t bother reading everything in the financial statements. In fact, five to ten ratios can tell you a lot about a business.

As a rule, you don’t find too many ratios in financial reports. Publicly owned businesses are required to report just one ratio (earnings per share, or EPS), and privately owned businesses generally don’t report any ratios. GAAP don’t demand that any ratios be reported (except EPS for publicly owned companies). However, you still see and hear about ratios all the time, especially from stockbrokers and other financial professionals, so you should know what the ratios mean, even if you never go to the trouble of computing them yourself.

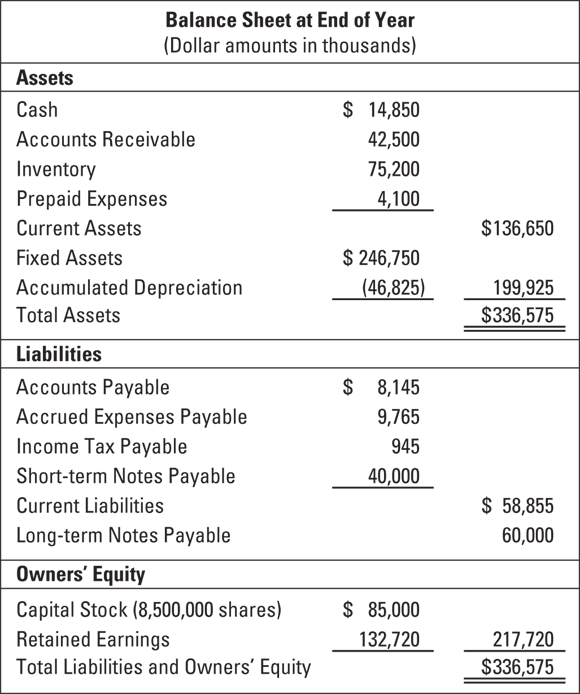

Figures 10-1 and 10-2 present an income statement and balance sheet for a business that serves as the example for the rest of the chapter. I don’t include a statement of cash flows because no ratios are calculated from data in this financial statement. Well, I should say that no cash flow ratios have yet become household names. I don’t present the footnotes to the company’s financial statements, but I discuss reading footnotes in the upcoming section “Frolicking through the Footnotes.” In short, the following discussion focuses on ratios from the income statement and balance sheet. Later, I return to the topic of cash flow ratios and why cash flow ratios haven’t become widespread benchmarks among financial statement analysts.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 10-1: Income statement example.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 10-2: Balance sheet example.

Gross margin ratio

Making bottom-line profit begins with making sales and earning sufficient gross margin from those sales. By sufficient, I mean that your gross margin must cover the expenses of making sales and operating the business, as well as paying interest and income tax expenses, so that there’s still an adequate amount left over for profit. You calculate the gross margin ratio as follows:

So a business with a $158.25 million gross margin and $457 million in sales revenue (refer to Figure 10-1) earns a 34.6 percent gross margin ratio. Now, suppose the business had been able to reduce its cost of goods sold expense and had earned a 35.6 percent gross margin. That one additional point (one point equals 1 percent) would have increased gross margin $4.57 million (1 percent × $457 million sales revenue) — which would have trickled down to earnings before income tax, assuming other expenses below the gross margin line had been the same (except income tax). Earnings before income tax would have been 9.3 percent higher:

Never underestimate the impact of even a small improvement in the gross margin ratio!

Investors can track the gross margin ratios for the two or three years whose income statements are included in the annual financial report, but they really can’t get behind gross margin numbers for the “inside story.” In their financial reports, public companies include a management discussion and analysis (MD&A) section that should comment on any significant change in the gross margin ratio. But corporate managers have wide latitude in deciding what exactly to discuss and how much detail to go into. You definitely should read the MD&A section, but it may not provide all the answers you’re looking for. You have to search further in stockbroker releases, in articles in the financial press, or at the next professional business meeting you attend.

As I explain in Chapter 12, business managers pay close attention to margin per unit and total margin in making and improving profit. Margin does not mean gross margin; rather, it refers to sales revenue minus product cost and all other variable operating expenses of a business. In other words, margin is profit before the company’s total fixed operating expenses (and before interest and income tax). Margin is an extremely important factor in the profit performance of a business. Profit hinges directly on margin.

Profit ratio

Business is motivated by profit, so the profit ratio is important, to say the least. The bottom line is called the bottom line with good reason. The profit ratio indicates how much net income was earned on each $100 of sales revenue:

The business in Figure 10-1 earned $32.47 million net income from its $457 million sales revenue, so its profit ratio equals 7.1 percent, meaning that the business earned $7.10 net income for each $100 of sales revenue. (Thus, its expenses were $92.90 per $100 of sales revenue.) Profit ratios vary widely from industry to industry. A 5- to 10-percent profit ratio is common in many industries, although some high-volume retailers, such as supermarkets, are satisfied with profit ratios around 1 or 2 percent.

Earnings per share (EPS), basic and diluted

Publicly owned businesses, according to GAAP, must report earnings per share (EPS) below the net income line in their income statements — giving EPS a certain distinction among ratios. Why is EPS considered so important? Because it gives investors a means of determining the amount the business earned on their stock share investments: EPS tells you how much net income the business earned for each stock share you own. The essential equation for EPS is as follows:

For the example in Figures 10-1 and 10-2, the company’s $32.47 million net income is divided by the 8.5 million shares of stock the business has issued to compute its $3.82 EPS.

Note: EPS is extraordinarily important to the stockholders of businesses whose stock shares are publicly traded. These stockholders pay close attention to market price per share. They want the net income of the business to be communicated to them on a per-share basis so they can easily compare it with the market price of their stock shares. The stock shares of privately owned corporations aren’t actively traded, so there’s no readily available market value for the stock shares. Private businesses don’t have to report EPS. The thinking behind this exemption is that their stockholders don’t focus on per-share values and are more interested in the business’s total net income.

The business in the example could be listed on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) or another securities exchange. Suppose that its capital stock is being traded at $70 per share. With 8.5 million shares trading at $70 per share, the company’s market cap is $595 million, which equals the current market price of its stock shares multiplied by the number of shares in the hands of stockholders. The word cap means capitalization, which in turn means the total amount of capital “invested,” as it were, in the business. (The actual, historical amount of capital invested in the business is found in the balance sheet, in particular in its capital stock and retained earnings accounts.) Market cap simply refers to the total market value of the business. Stock investors pay much more attention to EPS than market cap. As just explained, EPS expresses the net income (earnings) of the business on a per-share basis.

At the end of the year, this corporation has 8.5 million stock shares outstanding, which refers to the number of shares that have been issued and are owned by its stockholders. But here’s a complication: The business is committed to issuing additional capital stock shares in the future for stock options that the company has granted to its executives, and it has borrowed money on the basis of debt instruments that give the lenders the right to convert the debt into its capital stock. Under terms of its management stock options and its convertible debt, the business may have to issue 500,000 additional capital stock shares in the future. Dividing net income by the number of shares outstanding plus the number of shares that could be issued in the future gives the following computation of EPS:

This second computation, based on the higher number of stock shares, is called the diluted earnings per share. (Diluted means thinned out or spread over a larger number of shares.) The first computation, based on the number of stock shares actually issued and outstanding, is called basic earnings per share. Both are reported at the bottom of the income statement — see Figure 10-1.

- Issue additional stock shares and buy back some of its stock shares: (Shares of its stock owned by the business itself that aren’t formally cancelled are called treasury stock.) The weighted average number of outstanding stock shares is used in these situations.

- Issue more than one class of stock, causing net income to be divided into two or more pools — one pool for each class of stock: EPS refers to the common stock, or the most junior of the classes of stock issued by a business. (Let’s not get into tracking stocks here, in which a business divides itself into two or more sub-businesses and you have an EPS for each sub-part of the business; few public companies do this.)

Price/earnings (P/E) ratio

The price/earnings (P/E) ratio is another ratio that’s of particular interest to investors in public businesses. The P/E ratio gives you an idea of how much you’re paying in the current price for stock shares for each dollar of earnings (the net income being earned by the business). Remember that earnings prop up the market value of stock shares.

The P/E ratio is calculated as follows:

* If the business has a simple capital structure and doesn’t report a diluted EPS, its basic EPS is used for calculating its P/E ratio (see the preceding section).

The capital stock shares of the business in our example are trading at $70, and its diluted EPS for the latest year is $3.61. Note: For the remainder of this section, I use the term EPS; I assume you understand that it refers to diluted EPS for businesses with complex capital structures or to basic EPS for businesses with simple capital structures.

Stock share prices of public companies bounce around day to day and are subject to big changes on short notice. To illustrate the P/E ratio, I use the $70 price, which is the closing price on the latest trading day in the stock market. This market price means that investors trading in the stock think that the shares are worth about 19 times EPS ($70 market price ÷ $3.61 EPS = 19). This P/E ratio should be compared with the average stock market P/E to gauge whether the business is selling above or below the market average.

Over the last century, average P/E ratios have fluctuated more than you may think. I remember when the average P/E ratio was less than 10 and a time when it was more than 20. Also, P/E ratios vary from business to business, industry to industry, and year to year. One dollar of EPS may command only a $12 market value for a mature business in a no-growth industry, whereas a dollar of EPS for dynamic businesses in high-growth industries may be rewarded with a $35 market value per dollar of earnings (net income).

Dividend yield

The dividend yield ratio tells investors how much cash income they’re receiving on their stock investment in a business:

Suppose that our example business paid $1.50 in cash dividends per share over the last year, which is less than half of its EPS. (I should mention that the ratio of annual dividends per share divided by annual EPS is called the payout ratio.) You calculate the dividend yield ratio for this business as follows:

You can compare the dividend yields of different companies. However, the company that pays the highest dividend yield isn’t necessarily the best investment. The best investment depends on many factors, including forecasts of earnings and EPS in particular.

Traditionally, the interest rates on high-grade debt securities (U.S. Treasury bonds and Treasury notes being the safest) were higher than the average dividend yield on public corporations. In theory, market price appreciation of the stock shares made up for this gap. Of course, stockholders take the risk that the market value won’t increase enough to make their total return on investment rate higher than a benchmark interest rate. Recently, however, the yields on U.S. debt securities have fallen below the dividend yields on many corporate stocks.

Market value, book value, and book value per share

The amount reported in a business’s balance sheet for owners’ equity is called its book value. In the Figure 10-2 example, the book value of owners’ equity is $217.72 million at the end of the year. This amount is the sum of the accounts that are kept for owners’ equity, which fall into two basic types: capital accounts (for money invested by owners minus money returned to them) and retained earnings (profit earned and not distributed to the owners). Just like accounts for assets and liabilities, the entries in owners’ equity accounts are for the actual, historical transactions of the business.

Public companies have one advantage: You can easily determine the current market value of their ownership shares and the market cap for the business as a whole (equal to the number of shares times the market value per share.) The market values of capital stock shares of public companies are easy to find. Stock market prices of the largest public companies are reported every trading day in many newspapers and are available on the Internet.

Private companies have one disadvantage: There’s no active trading in their ownership shares to provide market value information. The shareowners of a private business probably have some idea of the price per share that they would be willing to sell their shares for, but until an actual buyer for their shares or for the business as a whole comes down the pike, market value isn’t known. Even so, in some situations, someone has to put a market value on the business and/or its ownership shares. For example, when a shareholder dies or gets a divorce, there’s need for a current market value estimate of the owner’s shares for estate tax or divorce settlement purposes. When making an offer to buy a private business, the buyer puts a value on the business, of course. The valuation of a private business is beyond the scope of this book. You can find more on this topic in a book my son, Tage, and I coauthored, Small Business Financial Management Kit For Dummies (Wiley).

In addition to or in place of market value per share, you can calculate book value per share. Generally, the actual number of capital stock shares issued is used for this ratio, not the higher number of shares used in calculating diluted EPS (see the earlier section “Earnings per share [EPS], basic and diluted”). The formula for book value per share is

The business shown in Figure 10-2 has issued 8.5 million capital stock shares, which are outstanding (in the hands of stockholders). The book value of its $217.72 million owners’ equity divided by this number of stock shares gives a book value per share of $25.61. If the business sold off its assets exactly for their book values and paid all its liabilities, it would end up with $217.72 million left for the stockholders, and it could therefore distribute $25.61 per share to them. But, of course, the company doesn’t plan to go out of business, liquidate its assets, and pay off its liabilities anytime soon.

Book value per share is important for value investors, who pay as much attention to the balance sheet factors of a business as to its income statement factors. They search out companies with stock market prices that aren’t much higher, or are even lower, than book value per share. Part of their theory is that such a business has more assets to back up the current market price of its stock shares, compared with businesses that have relatively high market prices relative to their book value per share. In the example, the business’s stock is selling for about 2.8 times its book value per share ($70 market price per share ÷ $25.61 book value per share = 2.8 times). This may be too high for some investors and would certainly give value investors pause before deciding to buy stock shares of the business.

Book value per share can be calculated for a private business, of course. But its capital stock shares aren’t publicly traded, so there’s no market price to compare the book value per share with. Suppose I own 1,000 shares of stock of a private business, and I offer to sell 100 of my shares to you. The book value per share might play some role in our negotiations. However, a more critical factor would be the amount of dividends per share the business will pay in the future, which depends on its earnings prospects. Your main income would be dividends, at least until you had an opportunity to liquidate the shares (which is uncertain for a private business).

Return on equity (ROE) ratio

The return on equity (ROE) ratio tells you how much profit a business earned in comparison to the book value of its owners’ equity. This ratio is especially useful for privately owned businesses, which have no easy way of determining the market value of owners’ equity. ROE is also calculated for public corporations, but just like book value per share, it generally plays a secondary role and isn’t the dominant factor driving market prices. Here’s how you calculate this ratio:

The business whose income statement and balance sheet are shown in Figures 10-1 and 10-2 earned $32.47 million net income for the year just ended and has $217.72 million owners’ equity at the end of the year. Therefore, its ROE is 14.9 percent:

Net income increases owners’ equity, so it makes sense to express net income as the percentage of improvement in the owners’ equity. In fact, this is exactly how Warren Buffett does it in his annual letter to the stockholders of Berkshire Hathaway. Over the 50 years ending in 2014, Berkshire Hathaway’s average annual ROE was 19.4 percent, which is truly extraordinary. See the sidebar “If you had invested $1,000 in Berkshire Hathaway in 1965.”

Current ratio

The current ratio is a test of a business’s short-term solvency — its capability to pay its liabilities that come due in the near future (up to one year). The ratio is a rough indicator of whether cash on hand plus the cash to be collected from accounts receivable and from selling inventory will be enough to pay off the liabilities that will come due in the next period.

As you can imagine, lenders are particularly keen on punching in the numbers to calculate the current ratio. Here’s how they do it:

Note: Unlike most other financial ratios, you don’t multiply the result of this equation by 100 and represent it as a percentage.

Businesses are generally expected to maintain a minimum 2-to-1 current ratio, which means a business’s current assets should be twice its current liabilities. In fact, a business may be legally required to stay above a minimum current ratio as stipulated in its contracts with lenders. The business in Figure 10-2 has $136,650,000 in current assets and $58,855,000 in current liabilities, so its current ratio is 2.3. The business shouldn’t have to worry about lenders coming by in the middle of the night to break its legs. Chapter 6 discusses current assets and current liabilities and how they’re reported in the balance sheet.

Acid-test (quick) ratio

Most serious investors and lenders don’t stop with the current ratio for testing the business’s short-term solvency (its capability to pay the liabilities that will come due in the short term). Investors, and especially lenders, calculate the acid-test ratio — also known as the quick ratio or less frequently as the pounce ratio — which is a more severe test of a business’s solvency than the current ratio. The acid-test ratio excludes inventory and prepaid expenses, which the current ratio includes, and it limits assets to cash and items that the business can quickly convert to cash. This limited category of assets is known as quick or liquid assets.

You calculate the acid-test ratio as follows:

Note: Like the current ratio, you don’t multiply the result of this equation by 100 and represent it as a percentage.

The business example in Figure 10-2 has two “quick” assets: $14.85 million cash and $42.5 million accounts receivable, for a total of $57.35 million. (If it had any short-term marketable securities, this asset would be included in its total quick assets.) Total quick assets are divided by current liabilities to determine the company’s acid-test ratio, as follows:

The 0.97 to 1.00 acid-test ratio means that the business would be just about able to pay off its short-term liabilities from its cash on hand plus collection of its accounts receivable. The general rule is that the acid-test ratio should be at least 1.0, which means that liquid (quick) assets should equal current liabilities. Of course, falling below 1.0 doesn’t mean that the business is on the verge of bankruptcy, but if the ratio falls as low as 0.5, that may be cause for alarm.

Return on assets (ROA) ratio and financial leverage gain

As I discuss in Chapter 6, one factor affecting the bottom-line profit of a business is whether it uses debt to its advantage. For the year, a business may realize a financial leverage gain, meaning it earns more profit on the money it has borrowed than the interest paid for the use of that borrowed money. In fact, a good part of a business’s net income for the year could be due to financial leverage.

The first step in determining financial leverage gain is to calculate a business’s return on assets (ROA) ratio, which is the ratio of EBIT (earnings before interest and income tax) to the total capital invested in operating assets. Here’s how to calculate ROA:

Note: This equation uses net operating assets, which equals total assets less the non-interest-bearing operating liabilities of the business. Actually, many stock analysts and investors use the total assets figure because deducting all the non-interest-bearing operating liabilities from total assets to determine net operating assets is, quite frankly, a nuisance. But I strongly recommend using net operating assets because that’s the total amount of capital raised from debt and equity.

Compare ROA with the interest rate: If a business’s ROA is, say, 14 percent and the interest rate on its debt is, say, 6 percent, the business’s net gain on its debt capital is 8 percent more than what it’s paying in interest. There’s a favorable spread of 8 points (1 point = 1 percent), which can be multiplied times the total debt of the business to determine how much of its earnings before income tax is traceable to financial leverage gain.

In Figure 10-2, notice that the business has $100 million total interest-bearing debt: $40 million short-term plus $60 million long-term. Its total owners’ equity is $217.72 million. So its net operating assets total is $317.72 million (which excludes the three short-term non-interest-bearing operating liabilities). The company’s ROA, therefore, is

The business earned $17.5 million (rounded) on its total debt — 17.5 percent ROA times $100 million total debt. The business paid only $6.25 million interest on its debt. So the business had $11.25 million financial leverage gain before income tax ($17.5 million less $6.25 million).

Cash flow ratios — not

No cash flow ratios serve as important benchmarks among financial statement analysts. You can find websites that feature cash flow ratios, but frankly, these ratios don’t have much clout. The statement of cash flows has been around for 30 years, but you’d be hard-pressed to point to even one cash flow ratio that has achieved the status and widespread use as the financial statement ratios I discuss earlier.

Cash flow ratios are in the minor leagues — for good reason. Ratios compare one number against another. Take, for example, the current ratio. Current assets are divided by current liabilities to get the current ratio. This result is a good indicator of the short-run solvency of the business — that is, its ability to pay its short-term liabilities on time from its cash balance plus the cash flow to be generated by its short-term liquid assets. A low ratio signals trouble ahead. What cash flow ratio could you use instead? You might try using cash flow from operating activities instead of current assets and dividing by current liabilities, but there’s not a natural pairing off of the two components of the ratio like there is in pitting current assets against current liabilities.

The proponents of cash flow ratios will have to come up with ratios that do a better job of providing insights into the financial affairs of a business. Given the relatively easy access to financial statement information databases, perhaps cash flow ratios will become more prominent in the future, but I doubt it.

More ratios?

The previous list of ratios is bare-bones; it covers the hardcore, everyday tools for interpreting financial statements. You could certainly calculate many more ratios from the financial statements, such as the inventory turnover ratio and the debt-to-equity ratio. (Chapter 11 explains additional ratios managers of a business use based on internal information that’s not revealed in its external financial statements.) How many ratios to calculate is a matter of judgment and is limited by the time you have for reading a financial report.

Computer-based databases are at our disposal, and it’s relatively easy to find many other financial statement ratios. Which of these additional ratios provide valuable insight?

Frolicking through the Footnotes

Reading the footnotes in annual financial reports is no walk in the park. The investment pros read them because in providing service and consultation to their clients, they’re required to comply with due diligence standards — or because of their legal duties and responsibilities of managing other peoples’ money. When I was an accounting professor, I had to stay on top of financial reporting; every year, I read a sample of annual financial reports to keep up with current practices. But beyond the group of people who get paid to read financial reports, does anyone read footnotes?

For a company you’ve invested in (or are considering investing in), I suggest that you do a quick read-through of the footnotes and identify the ones that seem to have the most significance. Generally, the most important footnotes are those dealing with the following:

- Stock options awarded by the business to its executives: The additional stock shares issued under stock options dilute (thin out) the earnings per share of the business, which in turn puts downside pressure on the market value of its stock shares, assuming everything else remains the same.

- Pending lawsuits, litigation, and investigations by government agencies: These intrusions into the normal affairs of the business can have enormous consequences.

- Employee retirement and other post-retirement benefit plans: Your concerns here should be whether these future obligations of the business are seriously underfunded. I have to warn you that this particular footnote is one of the most complex pieces of communication you’ll ever encounter. Good luck.

- Debt problems: It’s not unusual for companies to get into problems with their debt. Debt contracts with lenders can be very complex and are financial straitjackets in some ways. A business may fall behind in making interest and principal payments on one or more of its debts, which triggers provisions in the debt contracts that give its lenders various options to protect their rights. Some debt problems are normal, but in certain cases, lenders can threaten drastic action against a business, which should be discussed in its footnotes.

- Segment information for the business: Public businesses have to report information for the major segments of the organization — sales and operating profit by territories or product lines. This gives a better glimpse of the parts making up the whole business. (Segment information may be reported elsewhere in an annual financial report than in the footnotes, or you may have to go to the SEC filings of the business to find this information.)

Checking Out the Auditor’s Report

If a private business’s financial report doesn’t include an audit report, you have to trust that the business has prepared accurate financial statements according to applicable accounting and financial reporting standards and that the footnotes to the financial statements cover all important points and issues. One thing you could do is to find out the qualifications of the company’s chief accountant. Is the accountant a CPA? Does the accountant have a college degree with a major in accounting? Does the financial report omit a statement of cash flows or have any other obvious deficiencies?

Why audits?

The top managers, along with their finance and accounting officers, oversee the preparation of the company’s financial statements and footnotes (see Chapter 9 for details). These executives have a vested interest in the profit performance and financial condition of the business; their yearly bonuses usually depend on recorded profit, for example. This situation is somewhat like the batter in a baseball game calling the strikes and balls. Where’s the umpire? Independent CPA auditors are like umpires in the financial reporting game. The CPA comes in, does an audit of the business’s accounting system and methods, critically examines the financial statements, and gives a report that’s attached to the company’s financial statements.

I hope I’m not the first person to point this out to you, but the business world is not like Sunday school. Not everything is honest and straight. A financial report can be wrong and misleading because of innocent, unintentional errors or because of deliberate, cold-blooded fraud. Errors can happen because of incompetence and carelessness. Audits are one means of keeping misleading financial reporting to a minimum. The CPA auditor should definitely catch all major errors. The auditor’s responsibility for discovering fraud isn’t as clear-cut. You may think catching fraud is the purpose of an audit, but I’m sorry to tell you it’s not as simple as that.

What’s in an auditor’s report?

The large majority of financial statement audit reports give the business a clean bill of health, or what’s called a clean opinion. (The technical term for this opinion is an unmodified opinion, which means that the auditor doesn’t qualify or restrict his opinion regarding any significant matter.) At the other end of the spectrum, the auditor may state that the financial statements are misleading and shouldn’t be relied upon. This negative, disapproving audit report is called an adverse opinion. That’s the big stick that auditors carry: They have the power to give a company’s financial statements a thumbs-down opinion, and no business wants that.

The threat of an adverse opinion almost always motivates a business to give way to the auditor and change its accounting or disclosure in order to avoid getting the kiss of death of an adverse opinion. An adverse audit opinion says that the financial statements of the business are misleading. The SEC doesn’t tolerate adverse opinions by auditors of public businesses; it would suspend trading in a company’s securities if the company received an adverse opinion from its CPA auditor.

If the auditor finds no serious problems, the CPA firm gives the business’s financial report an unmodified or clean opinion. The key phrase auditors love to use is that the financial statements present fairly the financial position and performance of the business. However, I should warn you that the standard audit report has enough defensive, legalistic language to make even a seasoned accountant blush. If you have any doubts, go to the website of any public corporation and look at its most recent financial statements, particularly the auditor’s report.

The following summary cuts through the jargon and explains what the clean audit report really says:

Audit Report (Unmodified or Clean Opinion) |

|

1st paragraph |

We did an audit of the financial report of the business at the date and for the periods covered by the financial statements (which are specifically named). |

2nd paragraph |

Here’s a description of management’s primary responsibility for the financial statements, including enforcing internal controls for the preparation of the financial statements. |

3rd paragraph |

We carried out audit procedures that provide us a reasonable basis for expressing our opinion, but we didn’t necessarily catch everything. |

4th paragraph |

The company’s financial statements conform to accounting and financial reporting standards and are not misleading in any significant respect. |

An audit report that does not give a clean opinion may look similar to a clean-opinion audit report to the untrained eye. Some investors see the name of a CPA firm next to the financial statements and assume that everything is okay — after all, if the auditor had seen a problem, the Feds would have pounced on the business and put everyone in jail, right? Well, not exactly. For example, the auditor’s report may point out a flaw in the company’s financial statements but not a fatal flaw that would require an adverse opinion. In this situation, the CPA issues a modified opinion. The auditor includes a short explanation of the reasons for the modification. You don’t see this type of audit opinion that often, but you should read the auditor’s report to be sure.

Discovering fraud, or not

Auditors have trouble discovering fraud for several reasons. The most important reason, in my view, is that those managers who are willing to commit fraud understand that they must do a good job of concealing it. Managers bent on fraud are clever in devising schemes that look legitimate, and they’re good at generating false evidence to hide the fraud. These managers think nothing of lying to their auditors. Also, they’re aware of the standard audit procedures used by CPAs and design their fraud schemes to avoid audit scrutiny as much as possible.

Over the years, the auditing profession has taken somewhat of a wishy-washy position on the issue of whether auditors are responsible for discovering accounting and financial reporting fraud. The general public is confused because CPAs seem to want to have it both ways. CPAs don’t mind giving the impression to the general public that they catch fraud, or at least catch fraud in most situations. However, when a CPA firm is sued because it didn’t catch fraud, the CPA pleads that an audit conducted according to generally accepted auditing standards doesn’t necessarily discover fraud in all cases.

In the court of public opinion, it’s clear that people think that auditors should discover material accounting fraud — and, for that matter, auditors should discover any other fraud against the business by its managers, employees, vendors, or customers. CPAs refer to the difference between their responsibility for fraud detection (as they define it) and the responsibility of auditors perceived by the general public as the expectations gap. CPAs want to close the gap — not by taking on more responsibility for fraud detection but by lowering the expectations of the public regarding their responsibility.

You’d have to be a lawyer to understand in detail the case law on auditors’ legal liability for fraud detection, and I’m not a lawyer. But quite clearly, CPAs are liable for gross negligence in the conduct of an audit. If the judge or jury concludes that gross negligence was the reason the CPA failed to discover fraud, the CPA is held liable. (CPA firms have paid millions and millions of dollars in malpractice lawsuit damages.)

An audit would cost a lot more if extensive fraud detection procedures were used in addition to normal audit procedures. To minimize their audit costs, businesses assume the risk of not discovering fraud. They adopt internal controls (see Chapter 3) that are designed to minimize the incidence of fraud. But they know that clever fraudsters can circumvent the controls. They view fraud as a cost of doing business (as long as it doesn’t get out of hand).

One last point: In many accounting fraud cases that have been reported in the financial press, the auditor knew about the accounting methods of the client but didn’t object to the misleading accounting — you may call this an audit judgment failure. In these cases, the auditor was overly tolerant of questionable accounting methods used by the client. Perhaps the auditor had serious objections to the accounting methods, but the client persuaded the CPA to go along with the methods.

In many respects, the failure to object to bad accounting is more serious than the failure to discover accounting fraud, because it strikes at the integrity and backbone of the auditor. CPA ethical standards demand that a CPA resign from an audit if the CPA judges that the accounting or financial reporting by the client is seriously misleading. The CPA may have a tough time collecting a fee from the client for the hours worked up to the point of resigning.

Investors in a private business have just one main pipeline of financial information about the business they’ve put their hard-earned money in: its financial reports. Of course, investors should carefully read these reports. By “carefully,” I mean they should look for the vital signs of progress and problems. The financial statement ratios that I explain in this chapter point the way — like signposts on the financial information highway.

Investors in a private business have just one main pipeline of financial information about the business they’ve put their hard-earned money in: its financial reports. Of course, investors should carefully read these reports. By “carefully,” I mean they should look for the vital signs of progress and problems. The financial statement ratios that I explain in this chapter point the way — like signposts on the financial information highway. The more you know about interpreting a financial report, the better prepared you are to evaluate the commentary and advice of stock analysts and other investment experts. If you can at least nod intelligently while your stockbroker talks about a business’s P/E and EPS, you’ll look like a savvy investor — and you may get more favorable treatment. (P/E and EPS, by the way, are two of the key ratios explained later in the chapter.) You may regularly watch financial news on television or listen to one of today’s popular radio financial talk shows. The ratios explained in this chapter are frequently mentioned in the media. As a matter of fact, a business may include one or more of the ratios in its financial report (public companies have to disclose earnings per share, or EPS).

The more you know about interpreting a financial report, the better prepared you are to evaluate the commentary and advice of stock analysts and other investment experts. If you can at least nod intelligently while your stockbroker talks about a business’s P/E and EPS, you’ll look like a savvy investor — and you may get more favorable treatment. (P/E and EPS, by the way, are two of the key ratios explained later in the chapter.) You may regularly watch financial news on television or listen to one of today’s popular radio financial talk shows. The ratios explained in this chapter are frequently mentioned in the media. As a matter of fact, a business may include one or more of the ratios in its financial report (public companies have to disclose earnings per share, or EPS). Although accountants are loath to talk about it, the blunt fact is that many private companies simply ignore some authoritative standards in preparing their financial reports. This doesn’t mean that their financial reports are misleading — perhaps substandard, but not seriously misleading. In any case, a private business’s annual financial report is generally bare bones. It includes the three primary financial statements (balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows) plus some footnotes — and that’s about it. I’ve seen private company financial reports that don’t even have a letter from the president. In fact, I’ve seen financial reports of private businesses (mostly very small companies) that don’t include a statement of cash flows, even though this financial statement is required according to U.S. GAAP.

Although accountants are loath to talk about it, the blunt fact is that many private companies simply ignore some authoritative standards in preparing their financial reports. This doesn’t mean that their financial reports are misleading — perhaps substandard, but not seriously misleading. In any case, a private business’s annual financial report is generally bare bones. It includes the three primary financial statements (balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows) plus some footnotes — and that’s about it. I’ve seen private company financial reports that don’t even have a letter from the president. In fact, I’ve seen financial reports of private businesses (mostly very small companies) that don’t include a statement of cash flows, even though this financial statement is required according to U.S. GAAP. You can turn any ratio upside down and come up with a new way of looking at the same information. If you flip the profit ratio over to be sales revenue divided by net income, the result is the amount of sales revenue needed to make $1 profit. Using the same example, $457 million sales revenue ÷ $32.47 million net income = 14.08, which means that the business needs $14.08 in sales to make $1.00 profit. So you can say that net income is 7.1 percent of sales revenue, or you can say that sales revenue is 14.08 times net income.

You can turn any ratio upside down and come up with a new way of looking at the same information. If you flip the profit ratio over to be sales revenue divided by net income, the result is the amount of sales revenue needed to make $1 profit. Using the same example, $457 million sales revenue ÷ $32.47 million net income = 14.08, which means that the business needs $14.08 in sales to make $1.00 profit. So you can say that net income is 7.1 percent of sales revenue, or you can say that sales revenue is 14.08 times net income.