Chapter 8

Financial Accounting Issues

IN THIS CHAPTER

Disclosing changes in owners’ equity

Realizing there’s more than one way home

Grasping the impacts of alternative accounting methods in recording profit

Taking a closer look at cost of goods sold and depreciation expenses

Scanning the revenue and expense radar screen

In this chapter, I raise the topic of disclosure in external financial reports to the creditors and investors of a business. Actually, accountants prefer the term adequate disclosure. Accountants certainly don’t like the term full disclosure, which could involve a very high legal standard that might require providing highly sensitive information. Businesses don’t have to reveal everything in their external financial reports. Businesses are justified in protecting their competitive advantages by withholding disclosure about some matters. At the same time, business financial reports should reveal all the information that the creditors and investors are entitled to know about the business.

The three primary financial statements — income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement — constitute the bedrock disclosure by a business. Public companies are subject to many rules regarding the disclosure of information in addition to their three basic financial statements. Private companies should carefully consider what information they should disclose beyond their three primary financial statements in accordance with financial reporting standards. Virtually all businesses include (or should include) footnotes with their financial statements, which I discuss in Chapter 9.

One thing businesses do not have to disclose is how different their profit and financial condition would have been had they used alternative accounting methods. In recording revenue, expenses, and other transactions of a business, the accountant must choose among different methods for recording the economic reality of the transactions. You may think that accountants are in agreement on the exact ways of recording business transactions, but this isn’t the case. An old joke is that when two economists get together, there are three economic opinions; it’s no different in accounting.

Accounting for the economic activity of a business can be compared to selecting the best new book of the year. Judges may agree that the books on the short list for the prize are good, but the best book is sure to vary from judge to judge. The best accounting method is in the eye of the accountant.

Reporting Changes in Owners’ Equity

The three primary financial statements (income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement) — as important as they are — can’t convey all the information that the lenders and investors of a business want to know and are entitled to know, so a business should include additional information. One prime example is the statement of changes in owners’ equity. This statement supplements the information disclosed in the owners’ equity section of the balance sheet. The term statement is overkill, if you ask me. It’s more of a schedule or summary of the activities during the year that changed the company’s owners’ equity accounts.

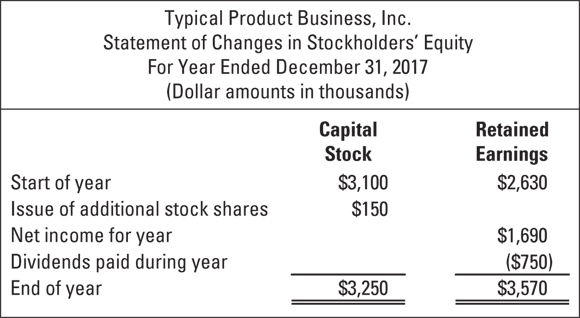

Figure 8-1 presents the statement of changes in stockholders’ equity for the product company example I use in the three preceding chapters. The company in the example had a minimum of transactions during the year involving its two owners’ equity accounts. The business operates as a corporation, so its invested capital account is labeled capital stock. You could argue that the statement is not really needed because the reader could pick up the same information from the company’s primary financial statements. However, presenting the statement of changes in stockholders’ equity is very convenient for the financial report reader.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 8-1: Simple example of a statement of changes in stockholders’ equity

Larger businesses generally have more complicated ownership structures than smaller and medium-size companies. Larger businesses are most often organized as corporations. (I discuss the legal organization of business in Chapter 4.) Corporations can issue more than one class of stock shares, and many do. One class may have preferences over the other class and thus is called preferred stock. A corporation may have both voting and nonvoting stock shares. Also, business corporations, believe it or not, can engage in cannibalization: They buy their own stock shares. A corporation may not cancel the shares it has purchased. Shares of itself that are held by the business are called treasury stock.

Well, I could go on and on, but the main point is that many businesses, especially larger public companies, engage in a broad range of activities during the year involving changes in their owners’ equity components. These owners’ equity activities tend to get lost from view in a comparative balance sheet and in the statement of cash flows. Yet the activities can be very important. Therefore, the business prepares a separate statement of changes in stockholders’ equity covering the same periods as its income statements. Some of these are monsters and have upwards of ten columns for the elements of stockholders’ equity.

The general format of the statement of changes in stockholders’ equity includes columns for each class of stock, treasury stock, retained earnings, and the comprehensive income element of owners’ equity. Professional stock analysts have to pore over these statements. Average financial report readers probably quickly turn the page when they see this statement, but it’s worth a quick glance if nothing else.

Recognizing Reasons for Accounting Differences

The financial statements reported by a business are just one version of its financial history and performance. A different accountant for the business undoubtedly would have recorded a different version, at least to some extent. The income statement and balance sheet of a business depend on which particular accounting methods the accountant chooses. Moreover, on orders from management, the financial statements could be tweaked to make them look better. I discuss how businesses can (and do!) put spin on their financial statements in Chapter 9.

The dollar amounts reported in the financial statements of a business aren’t simply “facts” that depend only on good bookkeeping. Here’s why different accountants record transactions differently. The accountant

- Must make choices among different accounting methods for recording the amounts of revenue and expenses

- Can select between pessimistic and optimistic estimates and forecasts when recording certain revenue and expenses

- Has some wiggle room in implementing accounting methods, especially regarding the precise timing of when to record sales and expenses

- Can carry out certain tactics at year-end to put a more favorable spin on the financial statements, usually under the orders or tacit approval of top management (I discuss these manipulations in Chapter 9)

A popular notion is that accounting is an exact science and that the amounts reported in the financial statements are true and accurate down to the last dollar. When people see an amount reported to the last digit in a financial statement, they naturally get the impression of exactitude and precision. However, in the real world of business, the accountant has to make many arbitrary choices between ways of recording revenue and expenses and of recording changes in their corresponding assets and liabilities. (In Chapter 5, I explain that revenue and expenses are coupled with assets and liabilities.)

I don’t discuss accounting errors in this chapter. It’s always possible that the accountant doesn’t fully understand the transaction being recorded or relies on misleading information, with the result that the entry for the transaction is wrong. And bookkeeping processing slip-ups happen. The term error generally refers to honest mistakes; there’s no intention of manipulating the financial statements. Unfortunately, a business may not detect accounting mistakes, and therefore its financial statements end up being misleading to one degree or another. (I point out in Chapter 3 that a business should institute effective internal controls to prevent accounting errors.)

Looking at a More Conservative Version of the Company’s Income Statement

Presenting an alternative income statement

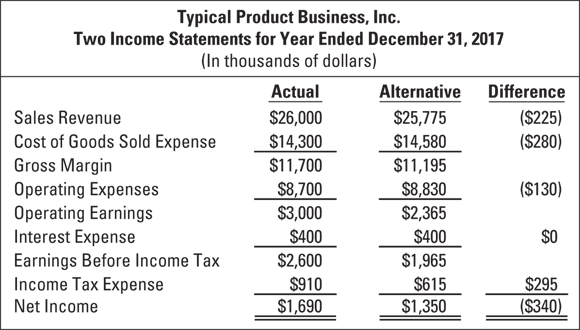

Figure 8-2 presents a comparison that you never see in real-life financial reporting. The Actual column presents the income statement reported by the business. The Alternative column reveals an income statement for the year that the business could have reported (but didn’t) if it had used alternative but acceptable accounting methods. The Difference column shows the impact on profit between the two methods. For example, sales revenue is less in the Alternative scenario, and thus profit is less, so you see a negative $225,000 difference. In the Alternative scenario, income tax expense is lower and thus profit is more, so you see a positive $295,000 difference in profit.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 8-2: Actual versus alternative income statements for a company.

If you’ve read Chapter 5, the Actual account balances in the income statement should be familiar — these are the same numbers from the financial statements I use in that chapter. The dollar amounts in the Alternative column are the amounts that would have been recorded using different accounting methods. You don’t need the statement of cash flows here, because cash flow from profit (operating activities) is the same amount under both accounting scenarios and because the cash flows from investing and financing activities are the same. Keep in mind these important points.

The business in our example adopted accounting methods that maximized its recorded profit by recognizing profit as soon as possible. Some businesses go the opposite direction. They adopt conservative accounting methods for recording profit performance, and they wouldn’t think of tinkering with their financial statements at the end of the year, even when their profit performance falls short of expectations and their financial condition has some trouble spots. The Alternative column in Figure 8-2 reports the results of conservative accounting methods. As you see, using alternative accounting methods results in a lower bottom line. Net income would have been $340,000 smaller, or 20 percent lower!

Now, you may very well ask, “Where in the devil did you get the numbers for the alternative financial statements?” The dollar amounts are my best estimates of what conservative numbers would be for this business — a company that has been in business for several years, has made a profit most years, and has not gone through bankruptcy. Both the Actual and the Alternative income statements are hypothetical but realistic and are not dishonest or deceitful.

Spotting significant differences

It’s a little jarring to see a second set of numbers for the income statement. You’re bound to raise your eyebrows when I say that both sets of accounting numbers are true and correct yet different. Financial report users have been conditioned to accept one version for financial statements without thinking about what alternative financial statements would look like. Seeing an alternative scenario takes a little time to get used to, like learning how to drive on the left side of the road in Great Britain. There’s always an alternative set of numbers lurking in the shadows, even though you don’t get to see them.

I don’t show the balance sheet differences in Figure 8-2, but they’d be sizable in the Alternative scenario. Accounts receivable and inventory would be significantly lower in the Alternative scenario, and the book value of the business’s fixed assets (original cost minus accumulated depreciation) would be significantly smaller. In both scenarios, the actual condition and usability of its fixed assets (space in its buildings, output of its machinery and equipment, future miles of its trucks, and so on) are the same. In the Alternative scenario, these key assets of the business just have a much lower reported value.

The company’s retained earnings balance would also be much lower in the Alternative scenario. Much less profit would have been recorded over the years if the business had used the Alternative accounting methods. Keep in mind that it took all the years of the business’s existence to accumulate the difference. The net income difference for its latest year (2017) is responsible for only $340,000 of the cumulative, total difference in retained earnings.

Explaining the Differences

- Recording sales revenue increases an asset (or decreases a liability in some cases).

- Recording an expense decreases an asset or increases a liability.

Therefore, assets are lower and/or liabilities are higher having used conservative accounting methods, and collectively these differences should equal the difference in retained earnings.

This section briefly explains each of the differences in Figure 8-2. I keep the explanations brief and to the point. The idea is to give you a taste of some of the reasons for the differences.

Accounts receivable and sales revenue

Here are some common reasons sales revenue and accounts receivable are lower when conservative accounting methods are adopted:

A business waits a little longer to record sales made on credit, to be more certain that all aspects of delivering products and the acceptance by customers are finalized and that there’s little chance the customers will return the products. This delay in recording sales causes its accounts receivable balance to be lower, because at December, some credit sales weren’t yet recorded because they were still in the process of final acceptance by the customers. (Of course, the cost of goods sold for these sales wouldn’t have been recorded.)

If products are returnable and the deal between the seller and buyer doesn’t satisfy normal conditions for a completed sale, the recording of sales revenue should be postponed until the return privilege no longer exists. For example, some products are sold on approval, which means the customer takes the product and tries it out for a few days or longer to see whether the customer really wants it.

Businesses should be consistent from year to year regarding when they record sales. For some businesses, the timing of recording sales revenue is a major problem — especially when the final acceptance by the customer depends on performance tests or other conditions that must be satisfied. Some businesses engage in channel stuffing by forcing their dealers or customers to take delivery of more products than they wanted to buy. A good rule to follow is to read the company’s footnote in its financial statements that explains its revenue recognition method, to see whether there’s anything unusual. If the footnote is vague, be careful — be very careful!

Businesses should be consistent from year to year regarding when they record sales. For some businesses, the timing of recording sales revenue is a major problem — especially when the final acceptance by the customer depends on performance tests or other conditions that must be satisfied. Some businesses engage in channel stuffing by forcing their dealers or customers to take delivery of more products than they wanted to buy. A good rule to follow is to read the company’s footnote in its financial statements that explains its revenue recognition method, to see whether there’s anything unusual. If the footnote is vague, be careful — be very careful!- A business may be quicker in writing off a customer’s past due balance as uncollectible. After it’s made a reasonable effort to collect the debt but a customer still hasn’t sent a check, a more conservative business writes off the balance as a bad debts expense. It decreases the past-due accounts receivable balance to zero and records an expense of the same amount. In contrast, a business could wait much longer to write off a customer’s past-due amount. Both accounting methods end up writing off a customer’s debt if it has been outstanding too long — but a company could wait until the last minute to make the write-off entry.

Inventory and cost of goods sold expense

The business in the example sells products mainly to other businesses. A business either manufactures the products it sells or purchases products for resale to customers. (Chapter 13 explains the determination of product costs for manufacturing businesses.) For this discussion, it isn’t too important whether the business manufactures or purchases the products it sells. The costs of its products have drifted upward over time because of inflation and other factors. The business increased its sales prices to keep up with the product cost increases. When product costs change, a business must choose which accounting method to use for recording cost of goods sold expense.

One accounting method takes product costs out of the inventory asset account and records the costs to the cost of goods sold expense in the sequence in which the costs were entered in the asset account. This scheme is called the first-in, first-out (FIFO) method. A business may instead choose to use the reverse method, in which the latest product costs entered in the inventory asset account are selected for recording the cost of goods sold expense, which leaves the oldest product costs in the asset account. This method is called the last-in, first-out (LIFO) method. I explain these opposing methods in more detail later in “Calculating Cost of Goods Sold Expense and Inventory Cost.” In Figure 8-2, FIFO is being used in the Actual scenario, and LIFO is what you see in the Alternative scenario.

When product costs drift upward over time, the FIFO method yields a lower cost of goods sold expense and a higher inventory asset balance compared with LIFO. In Figure 8-2, you see that cost of goods sold expense is $280,000 higher. The inventory balance would be lower, which makes total current assets in the balance sheet lower. The lower balance sheet value due to LIFO is the cumulative effect, which includes the carry-forward effects from previous years.

Fixed assets and depreciation expense

In the Actual accounting scenario, the business does include these additional costs in the original costs of its fixed assets, which means that the cost balances of its fixed assets are higher compared with the Alternative, conservative scenario. These additional costs aren’t expensed immediately but are included in the total amount to be depreciated over future years. Also, in the Actual scenario, the company uses straight-line depreciation (discussed later), which spreads out the cost of a fixed asset evenly over the years of its useful life.

In the conservative scenario, the business doesn’t include any costs other than purchase or construction costs in its fixed asset accounts, which means the additional costs are charged to expense immediately. Also, and most importantly, the business uses accelerated depreciation (discussed later) for allocating the cost of its fixed assets to expense. Higher amounts are allocated to early years, and smaller amounts, to later years. The result is that the accumulated depreciation amount in the Alternative scenario is higher, which signals that a lot more depreciation expense has been recorded over the years.

Accrued expenses payable, income tax payable, and expenses

A typical business at the end of the year has liabilities for certain costs that have accumulated but that won’t be paid until sometime after the end of the year — costs that are an outgrowth of the current year’s operating activities. The amounts of these delayed-payment expenses should be recorded and matched against the sales revenue for the year. For example, a business should accrue (calculate and record) the amount it owes to its employees for unused vacation and sick pay. A business may not have received its property tax bill yet, but it should estimate the amount of tax to be assessed and record the proper portion of the annual property tax to the current year. The accumulated interest on notes payable that hasn’t been paid yet at the end of the year should be recorded.

Here’s another example: Most products are sold with expressed or implied warranties and guarantees. Even when good quality controls are in place, some products sold by a business don’t perform up to promises, and the customers want the problems fixed. A business should estimate the cost of these future obligations and record this amount as an expense in the same period that the goods are sold (along with the cost of goods sold expense, of course). It shouldn’t wait until customers actually return products for repair or replacement, because if it waits to record the cost, then some of the expense for the guarantee work won’t be recorded until the following year. After being in business a few years, a company can forecast with reasonable accuracy the percent of products sold that will be returned for repair or replacement under the guarantees and warranties offered to its customers. On the other hand, brand-new products that have no track record may be a serious problem in this regard.

In the Actual scenario, the business doesn’t make the effort to estimate future product warranty and guarantee costs and certain other costs that should be accrued. It records these costs on a when-paid basis. It waits until it actually incurs these costs to record an expense. The company has decided that although its liabilities are understated, the amount is not material. In the Alternative scenario, on the other hand, the business takes the high road and goes to the trouble of estimating future costs that should be matched against sales revenue for the year. Therefore, its accrued expenses payable liability account is higher.

In the Alternative, conservative scenario (see Figure 8-2), I assume that the business uses the same accounting methods for income tax, which gives a lower taxable income and income tax for the year. Accordingly, the income tax expense for the year is $295,000 lower, and the year-end balance of income tax payable is lower. A business makes installment payments during the year on its estimated income tax for the year, so only a fraction of the annual income tax is still unpaid at the end of the year. (A business may use different accounting methods for income tax than it does for recording its transactions, which leads to complexities I don’t follow here.)

Wrapping things up

Calculating Cost of Goods Sold Expense and Inventory Cost

Companies that sell products must select which method to use for recording cost of goods sold expense, which is the sum of the costs of the products sold to customers during the period. You deduct cost of goods sold from sales revenue to determine gross margin — the first profit line on the income statement (see Figure 8-2). Cost of goods sold is a very important figure; if gross margin is wrong, bottom-line profit (net income) is wrong.

A business can choose between two opposite methods for recording its cost of goods sold and the cost balance that remains in its inventory asset account:

- The first-in, first-out (FIFO) cost sequence

- The last-in, first-out (LIFO) cost sequence

Other methods are acceptable, but these two are the primary options.

Product costs are entered in the inventory asset account in the order in which the products are acquired, but they aren’t necessarily taken out of the inventory asset account in this order. The FIFO and LIFO terms refer to the order in which product costs are taken out of the inventory asset account. You may think that only one method is appropriate; however, American accounting standards permit these two alternatives.

FIFO (first-in, first-out)

With the FIFO method, you charge out product costs to cost of goods sold expense in the chronological order in which you acquired the goods. The procedure is that simple. It’s like how the first people in line to see a movie get in the theater first. The ticket-taker collects the tickets in the order in which they were bought.

Suppose that you acquire four units of a product during a period, one unit at a time, with unit costs as follows (in the order in which you acquire the items): $100, $102, $104, and $106, for a total of $412. By the end of the period, you have sold three of these units. Using FIFO, you calculate the cost of goods sold expense as follows:

In short, you use the first three units to calculate cost of goods sold expense.

The cost of the ending inventory asset, then, is $106, which is the cost of the most recent acquisition. The $412 total cost of the four units is divided between the $306 cost of goods sold expense for the three units sold and the $106 cost of the one unit in ending inventory. The total cost has been accounted for; nothing has fallen between the cracks.

FIFO has two things going for it:

- Products generally move out of inventory in a first-in, first-out sequence. The earlier-acquired products are delivered to customers before later-acquired products are delivered, so the most recently purchased products are the ones still in ending inventory to be delivered in the future. Using FIFO, the inventory asset reported in the balance sheet at the end of the period reflects recent purchase (or manufacturing) costs, which means the balance in the asset is close to the current replacement costs of the products.

When product costs are steadily increasing, many (but not all) businesses follow a first-in, first-out sales price strategy and hold off raising sales prices as long as possible. They delay raising sales prices until they have sold their lower-cost products. Only when they start selling from the next batch of products, acquired at a higher cost, do they raise sales prices. I favor the FIFO cost of goods sold expense method when a business follows this basic sales pricing policy, because both the expense and the sales revenue are better matched for determining gross margin. I realize that sales pricing is complex and may not follow such a simple process, but the main point is that many businesses use a FIFO-based sales pricing approach. If your business is one of them, I urge you to use the FIFO expense method to be consistent with your sales pricing.

When product costs are steadily increasing, many (but not all) businesses follow a first-in, first-out sales price strategy and hold off raising sales prices as long as possible. They delay raising sales prices until they have sold their lower-cost products. Only when they start selling from the next batch of products, acquired at a higher cost, do they raise sales prices. I favor the FIFO cost of goods sold expense method when a business follows this basic sales pricing policy, because both the expense and the sales revenue are better matched for determining gross margin. I realize that sales pricing is complex and may not follow such a simple process, but the main point is that many businesses use a FIFO-based sales pricing approach. If your business is one of them, I urge you to use the FIFO expense method to be consistent with your sales pricing.

LIFO (last-in, first-out)

Imagine a movie ticket-taker goes to the back of a line of people waiting to get into the next showing and lets them in first. The later you bought your ticket, the sooner you get into the theater. This is what happens in the LIFO method, which stands for last-in, first-out. The people in the front of a movie line wouldn’t stand for it, of course, but for U.S. businesses, the LIFO method is acceptable for determining the cost of goods sold expense for products sold during the period.

The main feature of the LIFO method is that it selects the last item you purchased and then works backward until you have the total cost for the total number of units sold during the period. What about the ending inventory — the products you haven’t sold by the end of the year? Using the LIFO method, the earliest cost remains in the inventory asset account (unless all products are sold and the business has nothing in inventory).

Using the same example from the preceding section, assume that the business uses the LIFO method. The four units, in order of acquisition, had costs of $100, $102, $104, and $106. If you sell three units during the period, the LIFO method calculates the cost of goods sold expense as follows:

The ending inventory cost of the one unit not sold is $100, which is the oldest cost. The $412 total cost of the four units acquired less the $312 cost of goods sold expense leaves $100 in the inventory asset account. Determining which units you actually delivered to customers is irrelevant; when you use the LIFO method, you always count backward from the most recent unit you acquired.

The two main arguments in favor of the LIFO method are these:

- Assigning the most recent costs of products purchased to the cost of goods sold expense makes sense because you have to replace your products to stay in business, and the most recent costs are closest to the amount you’ll have to pay to replace your products. Ideally, you should base your sales prices not on original cost but on the cost of replacing the units sold.

- During times of rising costs, the most recent purchase cost maximizes the cost of goods sold expense deduction for determining taxable income and thus minimizes income tax. In fact, LIFO was invented for income tax purposes. True, the cost of inventory on the ending balance sheet is lower than recent acquisition costs, but the taxable income effect is more important than the balance sheet effect.

- Unless you’re able to base sales prices on the most recent purchase costs or you raise sales prices as soon as replacement costs increase — and most businesses would have trouble doing this — using LIFO depresses your gross margin and therefore your bottom-line net income.

- The LIFO method can result in an ending inventory cost value that’s seriously out of date, especially if the business sells products that have very long lives. For instance, for several years, Caterpillar’s LIFO-based inventory has been billions less than what it would have been under the FIFO method.

- Unscrupulous managers can use the LIFO method to manipulate their profit figures if business isn’t going well. They deliberately let their inventory drop to abnormally low levels, with the result that old, lower product costs are taken out of inventory to record the cost of goods sold expense. This gives a one-time boost to gross margin. These “LIFO liquidation gains” — if sizable in amount compared with the normal gross profit margin that would have been recorded using current costs — have to be disclosed in the footnotes to the company’s financial statements. (Dipping into old layers of LIFO-based inventory cost is necessary when a business phases out obsolete products; the business has no choice but to reach back into the earliest cost layers for these products. The sales prices of products being phased out usually are set low, to move the products out of inventory, so gross margin isn’t abnormally high for these products.)

If you sell products that have long lives and for which your product costs rise steadily over the years, using the LIFO method has a serious impact on the ending inventory cost value reported on the balance sheet and can cause the balance sheet to look misleading. Over time, the current cost of replacing products becomes further and further removed from the LIFO-based inventory costs. In our business example (Figure 8-2), the 2017 balance sheet may very well include products with 2003, 1997, or 1980 costs. The product costs reported for inventory could go back even further.

Note: A business must disclose in a footnote with its financial statements the difference between its LIFO-based inventory cost value and its inventory cost value according to FIFO. However, not many people outside of stock analysts and professional investment managers read footnotes very closely. Business managers get involved in reviewing footnotes in the final steps of getting annual financial reports ready for release (see Chapter 9). If your business uses FIFO, ending inventory is stated at recent acquisition costs, and you don’t have to determine what the LIFO value would have been.

One last note: FIFO and LIFO aren’t the only games in town. Businesses use other methods for cost of goods sold and inventory, including average cost methods, retail price–based methods, and so on. However, FIFO and LIFO dominate.

Recording Depreciation Expense

In theory, depreciation expense accounting is straightforward enough: You divide the cost of a fixed asset (except land) among the number of years that the business expects to use the asset. In other words, instead of having a huge lump-sum expense in the year in which you make the purchase, you charge a fraction of the cost to expense for each year of the asset’s lifetime. Using this method is much easier on your bottom line in the year of purchase, of course.

As it turns out, the IRS runs its own little psychic business on the side, with a crystal ball known as the Internal Revenue Code. Okay, so the IRS can’t tell you that your truck is going to conk out in five years, seven months, and two days. The Internal Revenue Code doesn’t predict how long your fixed assets will last; it only tells you what kind of timeline to use for income tax purposes as well as how to divide the cost along that timeline.

The IRS rules offer two depreciation methods that can be used for particular classes of assets. Buildings must be depreciated just one way, but for other fixed assets, you can take your pick:

Straight-line depreciation: With this method, you divide the cost evenly among the years of the asset’s estimated lifetime. Buildings have to be depreciated this way. Suppose that a building purchased by a business costs $390,000, and its useful life — according to the tax law — is 39 years. The depreciation expense is $10,000 (

of the cost) for each of the 39 years.

of the cost) for each of the 39 years.You may choose to use the straight-line method for other types of assets, too. After you start using this method for a particular asset, you can’t change your mind and switch to another depreciation method later.

- Accelerated depreciation: This term is a generic catchall for several methods. What they all have in common is that they’re front-loading methods, meaning that you charge a larger amount of depreciation expense in the early years and a smaller amount in the later years. The term accelerated also refers to adopting useful lives that are shorter than realistic estimates. (Very few automobiles are useless after five years, for example, but they can be fully depreciated over five years for income tax purposes.)

Fully depreciated fixed assets are grouped with all other fixed assets in external balance sheets. All these long-term resources of a business are reported in one asset account called property, plant, and equipment (instead of fixed assets). If all its fixed assets were fully depreciated, the balance sheet of a company would look rather peculiar — the cost of its fixed assets would be offset by its accumulated depreciation. Keep in mind that the cost of land (as opposed to the structures on the land) is not depreciated. The original cost of land stays on the books as long as the business owns the property.

Scanning the Revenue and Expense Radar Screen

Recording sales revenue and other income can present some hairy accounting problems. As a matter of fact, the accounting rule-making authorities rank revenue recognition as a major problem area. A good part of the reason for putting revenue recognition high on the list of accounting problems is that many high-profile financial accounting frauds have involved recording bogus sales revenue that had no economic reality. Sales revenue accounting presents challenging problems in some situations. But in my view, the accounting for many key expenses is equally important. Frankly, it’s damn difficult to measure expenses on a year-by-year basis.

I could write a book on expense accounting, which would have at least 20 or 30 major chapters. All I can do here is to call your attention to a few major expense accounting issues:

- Asset impairment write-downs: Inventory shrinkage, bad debts, and depreciation by their very nature are asset write-downs. Other asset write-downs are required when an asset becomes impaired, which means that it has lost some or all of its economic utility to the business and has little or no disposable value. An asset write-down reduces the book (recorded) value of an asset (and at the same time records an expense or loss of the same amount).

- Employee-defined benefits pension plans and other post-retirement benefits: The U.S. accounting rule on this expense is complex. Several key estimates must be made by the business, including the expected rate of return on the investment portfolio set aside for these future obligations. This and other estimates affect the amount of expense recorded. In some cases, a business uses an unrealistically high rate of return in order to minimize the amount of this expense. Using unrealistically optimistic rates of investment return continues to be a pernicious problem.

- Certain discretionary operating expenses: Many operating expenses involve timing problems and/or serious estimation problems. Furthermore, some expenses are discretionary in nature, which means how much to spend during the year depends almost entirely on the discretion of managers. Managers can defer or accelerate these expenses in order to manipulate the amount of expense recorded in the period. For this reason, businesses filing financial reports with the SEC are required to disclose certain expenses, such as repairs and maintenance expense and advertising expense. (To find examples, go to the Securities and Exchange Commission website at

www.sec.gov.) - Income tax expense: A business can use different accounting methods for some of the expenses reported in its income statement than it uses for calculating its taxable income. Oh, boy! The hypothetical amount of taxable income is calculated as if the accounting methods used in the income statement were used in the tax return; then the income tax based on this hypothetical taxable income is figured. This is the income tax expense reported in the income statement. This amount is reconciled with the actual amount of income tax owed based on the accounting methods used for income tax purposes. A reconciliation of the two different income tax amounts is provided in a technical footnote schedule to the financial statements.

Management stock options: A stock option is a contract between an executive and the business that gives the executive the option to purchase a certain number of the corporation’s capital stock shares at a fixed price (called the exercise or strike price) after certain conditions are satisfied. Usually a stock option doesn’t vest until the executive has been with the business for a certain number of years. The question is whether the granting of stock options should be recorded as an expense. This issue had been simmering for some time. The U.S. rule-making body finally issued a pronouncement that requires that a value measure be put on stock options when they’re issued and that this amount be recorded as an expense.

You could argue that management stock options are simply an arrangement between the stockholders and the privileged few executives of the business, by which the stockholders allow the executives to buy shares at bargain prices. The granting of stock options doesn’t reduce the assets or increase the liabilities of the business, so you could argue that stock options aren’t a direct expense of the business; instead, the cost falls on the stockholders. Allowing executives to buy stock shares at below-market prices increases the number of shares over which profit has to be spread, thus decreasing earnings per share. Stockholders have to decide whether they’re willing to do this; the granting of management stock options must be put to a vote by the stockholders.

You could argue that management stock options are simply an arrangement between the stockholders and the privileged few executives of the business, by which the stockholders allow the executives to buy shares at bargain prices. The granting of stock options doesn’t reduce the assets or increase the liabilities of the business, so you could argue that stock options aren’t a direct expense of the business; instead, the cost falls on the stockholders. Allowing executives to buy stock shares at below-market prices increases the number of shares over which profit has to be spread, thus decreasing earnings per share. Stockholders have to decide whether they’re willing to do this; the granting of management stock options must be put to a vote by the stockholders.

Please don’t think that the short list here does justice to all the expense accounting problems of businesses. U.S. businesses — large and small, public and private — operate in a highly developed and very sophisticated economy. One result is that expense accounting has become very complicated and confusing.

In particular, many public companies use the metric of earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) as a useful measure of their profit. You don’t have to read very far between the lines to see that these companies want to draw attention away from their income statements in order to put their profit performance in a more favorable light. In my view, these companies are trying to pull a fast one on investors. I admit that EBITDA has use in the management analysis of profit performance, but it’s not the final, all-things-considered measure of profit that investors should focus on. Net income, not EBITDA, is the bottom line.

Only one set of financial statements is included in a business’s financial report: one income statement, one balance sheet, and one statement of cash flows (and one statement of changes in owners’ equity). A business doesn’t provide a second, alternative set of financial statements that would have been generated if the business had used different accounting methods and if the business hadn’t tweaked its financial statements. The financial statements would have been different if alternative accounting methods had been used to record sales revenue and expenses and if the business hadn’t engaged in certain end-of-period maneuvers to make its financial statements look better. (My late father-in-law, a successful businessman, called these tricks of the trade “fluffing the pillows.”)

Only one set of financial statements is included in a business’s financial report: one income statement, one balance sheet, and one statement of cash flows (and one statement of changes in owners’ equity). A business doesn’t provide a second, alternative set of financial statements that would have been generated if the business had used different accounting methods and if the business hadn’t tweaked its financial statements. The financial statements would have been different if alternative accounting methods had been used to record sales revenue and expenses and if the business hadn’t engaged in certain end-of-period maneuvers to make its financial statements look better. (My late father-in-law, a successful businessman, called these tricks of the trade “fluffing the pillows.”)