Chapter 9

Getting a Financial Report Ready for Release

IN THIS CHAPTER

Reviewing the purposes of financial reports

Keeping up-to-date on accounting and financial reporting standards

Ensuring that disclosure is adequate

Nudging the numbers to make profit and solvency look better

Comparing financial reports of public and private companies

Dealing with information overload in financial reports

Financial statements are the core content of a financial report, to be sure. But the term financial report connotes more content than the basic set of financial statements. To start this chapter, I briefly review the three primary business financial statements. Then I move on to a broader view of what’s in a financial report.

Lest you think that accountants prepare the whole of a financial report, I explain the role of top management in preparing the financial report of a business. Accountants are the main actors in whipping together the financial statements of the business. That’s their job. Then the top-level managers of the business take over. The managers are the primary actors in deciding the additional content to put in the financial report, from the letter to the shareholders to a historical summary of the key financial data of the business.

I also call your attention to the seamy side of financial reporting. The company’s managers may put a spin on the financial statement numbers generated by the accountant. Managers may override the accountant’s numbers to make profit look better (or at least smoother year to year) or to improve the appearance of the company’s financial condition. In this chapter, I also compare the financial reports of the typical public corporation with those of private and smaller businesses.

Quickly Reviewing the Theory of Financial Reporting

Business managers, creditors, and investors rely on financial reports because these reports provide information regarding how the business is doing and where it stands financially. Like newspapers, financial reports deliver financial “news” about the business. One big difference between newspapers and business external financial reports is that businesses themselves, not independent reporters, decide what goes into their financial reports. If you read financial information on websites, such as Yahoo! Finance, for instance, keep in mind that the information comes from the financial reports prepared and issued by the business.

Starting with the financial statements

In Chapters 5, 6, and 7, I explain the fundamentals of the three primary financial statements of a business. To review briefly:

- Income statement: The income statement summarizes sales revenue and other income (if any) and expenses and losses (if any) for the period. It ends with the bottom-line profit for the period, which most commonly is called net income or net earnings. (Inside a business, a profit performance statement is commonly called the profit and loss, or P&L, report.)

- Balance sheet: The balance sheet summarizes the financial condition, consisting of amounts of assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity at the closing date of the income statement period (and at other times as needed by managers). Its formal name is the statement of financial condition or statement of financial position.

- Statement of cash flows: The statement of cash flows reports the net cash increase or decrease during the period from the profit-making activities reported in the income statement and the reasons this key figure is different from bottom-line net income for the period. It also summarizes sources and uses of cash during the period from investing and financing activities.

This troika of financial statements constitutes the bedrock of a financial report. At a minimum, every financial report should include these three financial statements and their footnotes. (Caution: Smaller private businesses are notoriously skimpy on their footnotes.)

The three primary statements, plus footnotes to the financials and other content, are packaged in an annual financial report that is distributed to the company’s investors and lenders so they can keep tabs on the business’s financial health and performance. Abbreviated versions of their annual reports are distributed quarterly by public companies, as required by federal securities laws. Private companies do not have to provide interim financial reports, though many do. In this chapter, I shine a light on the process of preparing the annual financial report so you can recognize key decisions that must be made before a financial report hits the streets.

Keeping in mind the reasons for financial reports

A financial report is designed to answer certain basic financial questions:

- Is the business making a profit or suffering a loss, and how much?

- How do assets stack up against liabilities?

- Where did the business get its capital, and is it making good use of the money?

- What is the cash flow from the profit or loss for the period?

- Did the business reinvest all its profit or distribute some of the profit to owners?

- Does the business have enough capital for future growth?

In short, the purpose of financial reporting is to deliver important information that the lenders and owners of the business need and are entitled to receive. Financial reporting is part of the essential contract between a business and its lenders and investors. Although lawyers may not like this, the contract can be stated in a few words:

Give us your money, and we’ll give you the information you need to know regarding how we’re doing with your money.

Financial reporting is governed by statutory and common law, and it should abide by ethical standards. Unfortunately, financial reporting sometimes falls short of both legal and ethical standards.

Recognizing Top Management’s Role

The annual financial report of a business consists of the three primary financial statements with their footnotes and a variety of additional content, such as photographs of executives, vision statements, highlights of key financial performance measures, letters to stockholders from top management, and more. Public companies provide considerably more content than private companies. Much of the additional content falls outside the realm of financial accounting and to a large extent is at the discretion of the business.

The business’s top managers assisted by their top lieutenants play an essential role in the preparation of the financial reports of the company — which they (and outside investors and lenders) should understand. The managers should perform certain critical steps before the financial report of the company is released to the outside world:

Confer with the company’s chief financial officer and controller (chief accountant) to make sure that the latest accounting and financial reporting standards and requirements have been applied in its financial report. (A smaller business may consult with an independent CPA on these matters.)

In recent years, we’ve seen a high degree of flux in accounting and financial reporting standards and requirements. The U.S. and international rule-making bodies as well as the U.S. federal regulatory agency, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), have been very busy. International financial accounting and reporting standards haven’t taken root in the U.S., although recently (late 2015), the SEC indicated its inclination to allow U.S. companies to include international-standards-compliant information as an “add on” in their U.S.-based financial statements.

Looking in the other direction, small and medium-sized businesses are urged by the AICPA to adopt a separate financial reporting framework. And private companies can adopt certain alternative accounting methods. A business needs to know how it fits into the general classification of business entities (public or private, large or small to medium-sized).

A business and its independent CPA auditors can’t simply assume that the accounting methods and financial reporting practices that have been used for many years are still correct and adequate. A business must check carefully whether it’s in full compliance with current accounting standards and financial reporting requirements.

A business and its independent CPA auditors can’t simply assume that the accounting methods and financial reporting practices that have been used for many years are still correct and adequate. A business must check carefully whether it’s in full compliance with current accounting standards and financial reporting requirements.Carefully review the disclosures to be made in the financial report.

The top managers and financial officers of the business should make sure that the disclosures — all information other than the financial statements — are adequate according to financial reporting standards and that all the disclosure elements are truthful but not unnecessarily damaging to the business. Ideally, the disclosures should be written in clear language. I mention this because many disclosures seem purposely difficult to read (excuse me for getting on the soapbox here).

This disclosure review can be compared with the concept of due diligence, which is done to make certain that all relevant information is collected, that the information is accurate and reliable, and that all relevant requirements and regulations are being complied with. This step is especially important for public corporations whose securities (stock shares and debt instruments) are traded on securities exchanges. Public businesses fall under the jurisdiction of federal securities laws, which require technical and detailed filings with the SEC.

This disclosure review can be compared with the concept of due diligence, which is done to make certain that all relevant information is collected, that the information is accurate and reliable, and that all relevant requirements and regulations are being complied with. This step is especially important for public corporations whose securities (stock shares and debt instruments) are traded on securities exchanges. Public businesses fall under the jurisdiction of federal securities laws, which require technical and detailed filings with the SEC.Consider whether the financial statement numbers need touching up.

I know, this sounds a little suspicious, doesn’t it? It’s not as bad as putting lipstick on a pig. The idea is to smooth the jagged edges of the company’s year-to-year profit gyrations or to improve the business’s short-term solvency picture. Although this can be described as putting your thumb on the scale, you can argue that sometimes the scale is a little out of balance to begin with, and the manager should approve adjusting the numbers in the financial statements in order to make them jibe better with the normal circumstances of the business.

When I discuss touching up the financial statement numbers, I’m venturing into a gray area that accountants don’t much like to talk about. These topics are rather delicate. Nevertheless, in the real world of business, top-level managers have to strike a balance between the interests of the business on the one hand and the interests of its owners (investors) and creditors on the other. For a rough comparison, think of the advertising done by a business. Advertising should be truthful, but businesses have a lot of leeway regarding how to advertise their products, and much advertising uses a lot of hyperbole. Managers exercise the same freedoms in putting together their financial reports. Financial reports may have some hype, and managers may put as much positive spin on bad news as possible without making deceitful and deliberately misleading comments. See the later section “Putting a Spin on the Numbers (Short of Cooking the Books)” for details.

When I discuss touching up the financial statement numbers, I’m venturing into a gray area that accountants don’t much like to talk about. These topics are rather delicate. Nevertheless, in the real world of business, top-level managers have to strike a balance between the interests of the business on the one hand and the interests of its owners (investors) and creditors on the other. For a rough comparison, think of the advertising done by a business. Advertising should be truthful, but businesses have a lot of leeway regarding how to advertise their products, and much advertising uses a lot of hyperbole. Managers exercise the same freedoms in putting together their financial reports. Financial reports may have some hype, and managers may put as much positive spin on bad news as possible without making deceitful and deliberately misleading comments. See the later section “Putting a Spin on the Numbers (Short of Cooking the Books)” for details.

Keeping Current with Financial Accounting and Reporting Standards

Without a doubt, the rash of accounting and financial reporting scandals over the period of 1980–2000 (and continuing today) was one reason for the step-up in activity by the standard-setters. The infamous Enron accounting fraud scandal brought down a major international CPA firm (Arthur Andersen) and led to the passage of federal legislation that requires public companies to report on their internal controls to prevent financial reporting fraud. Furthermore, CPA auditors have come under increasing pressure to do better audits, especially by the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, which is an arm of the SEC.

The other reason for the heightened pace of activity by the standard-setters is the increasing complexity of doing business. When you look at how business is being conducted these days, you find more and more complexity — for example, the use of financial derivative contracts and instruments. It’s difficult to put definite gain and loss values on these financial devices before the day of reckoning (when the contracts terminate). The legal exposure of businesses has expanded, especially in respect to environmental laws and regulations.

In my view, the standard-setters should be given a lot of credit for their attempts to deal with the problems that have emerged in recent decades and for trying to prevent repetition of the accounting scandals of the past. But the price of doing so has been a rather steep increase in the range and rapidity of changes in accounting and financial reporting standards and requirements. Top-level managers of businesses have to make sure that the financial and accounting officers of the business are keeping up with these changes and make sure that their financial reports follow all current rules and regulations. Managers lean heavily on their chief financial officers and controllers for keeping in full compliance with accounting and financial reporting standards.

Making Sure Disclosure Is Adequate

The financial statements are the backbone of a financial report. In fact, a financial report isn’t deserving of the name if financial statements aren’t included. But a financial report is much more than just the financial statements; a financial report needs disclosures. Of course, the financial statements themselves provide disclosure of important financial information about the business. The term disclosures, however, usually refers to additional information provided in a financial report.

The CEO of a public corporation, the president of a private corporation, or the managing partner of a partnership has the primary responsibility to make sure that the financial statements have been prepared according to applicable accounting and reporting standards and that the financial report provides adequate disclosure. He or she works with the chief financial officer and controller of the business to make sure that the financial report meets the standard of adequate disclosure. (Many smaller businesses hire an independent CPA to advise them on their financial reports.)

For a quick survey of disclosures in financial reports, the following distinctions are helpful:

- Footnotes provide additional information about the figures included in the financial statements. Virtually all financial statements need footnotes to provide additional information for several of the items included in the three financial statements. (Even so, many small companies include only the bare bones of footnotes or no footnotes at all.)

- Supplementary financial schedules and tables to the financial statements provide more details than can be included in the body of financial statements.

- A wide variety of other information is presented, some of which is required if the business is a public corporation subject to federal regulations regarding financial reporting to its stockholders. Other information is voluntary and not strictly required legally or by financial reporting standards that apply to the business.

Footnotes: Nettlesome but needed

Footnotes are attached to the three primary financial statements and are usually placed at the end of the financial statements. Within the financial statements, you see references to particular footnotes. And at the bottom of each financial statement, you find the following sentence (or words to this effect): “The footnotes are integral to the financial statements.”

You should read all footnotes for a full understanding of the financial statements, although I should mention that some footnotes are dense and technical. For one exercise, try reading a footnote that explains how a public corporation puts the value on its management stock options in order to record the expense for this component of management compensation. Then take two aspirin to get rid of your headache.

Footnotes come in two types:

- One or more footnotes identify the major accounting policies and methods that the business uses. The business must reveal the principal accounting methods it uses for booking its revenue and expenses. In particular, the business must identify its cost of goods sold and depreciation expense methods. Some businesses have unusual problems regarding the timing for recording sales revenue, and a footnote should clarify their revenue recognition method. Other accounting methods that have a material impact on the financial statements are disclosed in footnotes as well. (Chapter 8 explains that a business must choose among alternative accounting methods for recording revenue and expenses and for their corresponding assets and liabilities.)

- Other footnotes provide additional information and details for many assets and liabilities. For example, a business may owe money on many short-term and longer-term debt issues; a footnote presents a schedule of maturity dates and interest rates of the debt issues. Details about stock option plans for executives are the main type of footnote for the capital stock account in the stockholders’ equity section of the balance sheet of corporations.

Some footnotes are always required; a financial report would be naked without them. Deciding whether a footnote is needed (after you get beyond the obvious ones disclosing the business’s accounting methods) and how to write the footnote is largely a matter of judgment and opinion. The general benchmark is whether footnote information is relevant to the investors and creditors of the business. But how relevant? This is the key question. For public companies, keep in mind that the SEC lays down specific requirements regarding disclosures in the quarterly and annual filings with the SEC.

Look at the following footnote from Caterpillar’s annual report. For your reading pleasure, here’s footnote D in its 2014 annual 10-K report filed with the SEC (page A-13):

- D. Inventories: Inventories are stated at the lower of cost or market. Cost is principally determined using the last-in, first-out (LIFO) method. The value of inventories on the LIFO basis represented about 60% of total inventories at December 31, 2014, 2013, and 2012.

- If the FIFO (first-in, first-out) method had been in use, inventories would have been $2,430 million, $2,504 million and $2,750 million higher than reported at December 31, 2014, 2013, and 20012 respectively.

Yes, these dollar amounts are in millions of dollars. Caterpillar’s inventory cost value for its inventories at the end of 2014 would have been $2,430 million (or $2.43 billion) higher if the FIFO accounting method had been used. Of course, it helps to have to have a basic understanding of the difference between the two accounting methods — LIFO and FIFO — to make sense of this note (see Chapter 8).

Other disclosures in financial reports

The following discussion includes a fairly comprehensive list of the various types of disclosures (in addition to footnotes) found in annual financial reports of publicly owned businesses. A few caveats are in order:

- Not every public corporation includes every one of the following items, although the disclosures are fairly common.

- The level of disclosure by private businesses — after you get beyond the financial statements and footnotes — is generally much less than in public corporations. A private business may include one or more of the following disclosures, but by and large, it isn’t required to do so — and in my experience, only a minority do.

- Tracking the actual disclosure practices of private businesses is difficult because their annual financial reports are circulated only to their owners and lenders. In other words, a private business keeps its financial report as private as possible.

In addition to the three financial statements and footnotes to the financials, public corporations typically include the following disclosures in their annual financial reports to their stockholders:

- Cover (or transmittal) letter: A letter from the chief executive of the business to the stockholders, which usually takes credit for good news and blames bad news on big government, unfavorable world political developments, a poor economy, or something else beyond management’s control

- Management’s report on internal control over financial reporting: An assertion by the chief executive officer and chief financial officer regarding their satisfaction with the effectiveness of the internal controls of the business, which are designed to ensure the reliability of its financial reports and to prevent financial and accounting fraud

- Highlights table: A table presenting key figures from the financial statements, such as sales revenue, total assets, profit, total debt, owners’ equity, number of employees, and number of units sold (such as the number of vehicles sold by an automobile manufacturer or the number of “revenue seat miles” flown by an airline, meaning one airplane seat occupied by a paying customer for 1 mile); the idea is to give the stockholder a financial thumbnail sketch of the business

- Management discussion and analysis (MD&A): A discussion of the major developments and changes during the year that affected the financial performance and situation of the business (by the way, the SEC requires this disclosure to be included in the annual financial reports of publicly owned corporations)

- Segment information: A report of the sales revenue and operating profits (before interest and income tax and perhaps before certain costs that cannot be allocated among different segments) for the major divisions of the organization or for its different markets (international versus domestic, for example)

- Historical summaries: A financial history that extends back three years or longer that includes information from past financial statements

- Graphics: Bar charts, trend charts, and pie charts representing financial conditions; photos of key people and products

Promotional material: Information about the company, its products, its employees, and its managers, often stressing an overarching theme for the year

Most companies use their annual financial report as an advertising or public relations opportunity.

Profiles: Information about members of top management and the board of directors

Of course, everyone appears to be well-qualified for his or her position. Negative information (such as prior brushes with the law) is not reported. One interesting development in recent years is that several high-level executives have lied about their academic degrees.

- Quarterly summaries of profit performance and stock share prices: Summaries that show financial performance for all four quarters in the year and stock price ranges for each quarter (required by the SEC for public companies)

Management’s responsibility statement: A short statement indicating that management has primary responsibility for the accounting methods used to prepare the financial statements, for writing the footnotes to the statements, and for providing the other disclosures in the financial report

Usually, this statement appears near the independent CPA auditor’s report.

Independent auditor’s report: The report from the CPA firm that performed the audit, expressing an opinion on the fairness of the financial statements and accompanying disclosures

Public corporations are required to have audits; private businesses may or may not have their annual financial reports audited. Unfortunately, the wording of audit reports has become more and more difficult to understand. The standards that govern CPA audit reports have mimicked the trend of accounting and financial reporting standards. Audit reports used to be three paragraphs that you could understand with careful reading. Even I can’t be sure about some audit reports I read these days.

- Company contact information: Information on how to contact the company, the web address of the company, how to get copies of the reports filed with the SEC, the stock transfer agent and registrar of the company, and other information

I should mention that annual financial reports have virtually no humor — no cartoons, no one-liners, no jokes. (Well, the CEO’s letter to shareowners may have some humorous comments, even when the CEO doesn’t mean to be funny.) Financial reports are written in a somber and serious vein. The tone of most annual financial reports is that the fate of the Western world depends on the financial performance of the company. Gimme a break!

Managers of public corporations rely on lawyers, CPA auditors, and their financial and accounting officers to make sure that everything that should be disclosed in the business’s annual financial reports is included and that the exact wording of the disclosures is not misleading, inaccurate, or incomplete. This is a tall order.

Putting a Spin on the Numbers (Short of Cooking the Books)

This section discusses two accounting tricks that involve manipulating, or “massaging,” the accounting numbers. I don’t endorse either technique, but you should be aware of both.

In some situations, the financial statement numbers don’t come out exactly the way the business prefers. With the connivance of top management, accountants can use certain tricks of the trade — some would say sleight of hand, or shenanigans — to move the numbers closer to what the business prefers. One trick improves the appearance of the short-term solvency of the business and the cash balance reported in its balance sheet at the end of the year. The other device shifts some profit from one year to the next to report a smoother trend of net income from year to year.

Window dressing: Pumping up the ending cash balance and cash flow

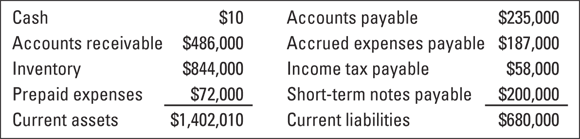

Suppose you manage a business and your controller has just submitted for your review the preliminary, or first draft, of the year-end balance sheet. (Chapter 6 explains the balance sheet, and Figure 6-2 shows a balance sheet for a business.) Figure 9-1 shows the current assets and current liabilities sections of the balance sheet draft, which is all we need here.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 9-1: Current assets and current liabilities of a business, before window dressing.

Wait a minute: a $10 cash balance? How can that be? Maybe your business has been having some cash flow problems and you’ve intended to increase your short-term borrowing and speed up collection of accounts receivable to help the cash balance. No one likes to see a near-zero cash balance — it makes them kind of nervous, to put it mildly, no matter how you try to cushion it. So what do you do to avoid setting off alarm bells?

Window dressing reduces the amount in accounts receivable and increases the amount in cash the same amount — it has no effect on your profit figure for the period. It makes your cash balance look a touch better. Window dressing can also be used to improve other accounts’ balances, which I don’t go into here. All these techniques involve holding the books open to record certain events that take place after the end of the fiscal year (the ending balance sheet date) to make things look better than they actually were at the close of business on the last day of the year.

Sounds like everybody wins, doesn’t it? You look like you’ve done a better job as manager, and your lenders and investors don’t panic. Right? Wrong! Window dressing is deceptive to your creditors and investors, who have every right to expect that the end of your fiscal year as stated on your financial reports is truly the end of your fiscal year. I should mention, however, that when I was in auditing, I encountered situations in which a major lender of the business was fully aware that it had engaged in window dressing. The lender did not object because it wanted the business to fluff the pillows to make its balance sheet look better. The loan officer wanted to make the loan to make the business look better. Essentially, the lender was complicit in the accounting manipulation.

Be aware that window dressing improves cash flow from operating activities, which is an important number in the statement of cash flows that creditors and investors closely watch. (I discuss the statement of cash flows and cash flow from operating activities in Chapter 7.) Suppose, for example, that a business holds open its cash receipts journal for several days after the close of its fiscal year. The result is that its ending cash balance is reported $3.25 million higher than the business actually had in its checking accounts on the balance sheet date. Also, its accounts receivable balance is reported $3.25 million lower than was true at the end of its fiscal year. This makes cash flow from profit (operating activities) $3.25 million higher, which could be the main reason in the decision to do some window dressing.

Smoothing the rough edges off year-to-year profit fluctuations

You shouldn’t be surprised when I tell you that business managers are under tremendous pressure to make profit and keep profit on the up escalator year after year. Managers strive to make their numbers and to hit the milestone markers set for the business. Reporting a loss for the year, or even a dip below the profit trend line, is a red flag that stock analysts and investors view with alarm. Everyone likes to see a steady upward trend line for profit; no one likes to see a profit curve that looks like a roller coaster. Most investors want a smooth journey and don’t like putting on their investment life preservers.

Managers can do certain things to deflate or inflate profit (net income) recorded in the year, which are referred to as profit smoothing techniques. Other names for these techniques are income smoothing and earnings management. Profit smoothing is like a white lie told for the good of the business and perhaps for the good of managers as well. Managers know that there’s always some noise in the accounting system. Profit smoothing muffles the noise.

The pressure on public companies

Managers of publicly owned corporations whose stock shares are actively traded are under intense pressure to keep profits steadily rising. Security analysts who follow a particular company make profit forecasts for the business, and their buy/hold/sell recommendations are based largely on these earnings forecasts. If a business fails to meet its own profit forecast or falls short of stock analysts’ forecasts, the market price of its stock shares usually takes a hit. Stock option and bonus incentive compensation plans are also strong motivations for achieving the profit goals set for the business.

Compensatory effects

Most profit smoothing involves pushing some amount of revenue and/or expenses into years other than those in which they would normally be recorded. For example, if the president of a business wants to report more profit for the year, he or she can instruct the chief accountant to accelerate the recording of some sales revenue that normally wouldn’t be recorded until next year or to delay the recording of some expenses until next year that normally would be recorded this year.

Chapter 8 explains that managers choose among alternative accounting methods for several important expenses (and for revenue as well). After making these key choices, the managers should let the accountants do their jobs and let the chips fall where they may. If bottom-line profit for the year turns out to be a little short of the forecast or target for the period, so be it. This hands-off approach to profit accounting is the ideal way. However, managers often use a hands-on approach — they intercede (one could say interfere) and override the normal methods for recording sales revenue or expenses.

Management discretion in the timing of revenue and expenses

Several smoothing techniques are available for filling the potholes and straightening the curves on the profit highway. Most profit-smoothing techniques require one essential ingredient: management discretion in deciding when to record expenses or when to record sales. See the sidebar “Case study in massaging the numbers.”

A common technique for profit smoothing is to delay normal maintenance and repairs, which is referred to as deferred maintenance. Many routine and recurring maintenance costs required for autos, trucks, machines, equipment, and buildings can be put off, or deferred, until later. These costs are not recorded to expense until the actual maintenance is done, so putting off the work means recording the expense is delayed.

Here are a few other techniques used:

- A business that spends a fair amount of money for employee training and development may delay these programs until next year so the expense this year is lower.

- A company can cut back on its current year’s outlays for market research and product development (though this could have serious long-term effects).

- A business can ease up on its rules regarding when slow-paying customers are written off to expense as bad debts (uncollectible accounts receivable). The business can, therefore, put off recording some of its bad debts expense until next year.

- A fixed asset out of active use may have very little or no future value to a business. But instead of writing off the undepreciated cost of the impaired asset as a loss this year, the business may delay the write-off until next year.

Keep in mind that most of these costs will be recorded next year, so the effect is to rob Peter (make next year absorb the cost) to pay Paul (let this year escape the cost).

Comparing Public and Private Companies

Suppose you had the inclination (and the time!) to compare 100 annual financial reports of publicly owned corporations with 100 annual reports of privately owned businesses (assuming you could assemble 100 private company financial reports). You’d see many differences. Public companies are generally much larger (in terms of annual sales and total assets) than private companies, as you would expect. Furthermore, public companies generally are more complex — concerning employee compensation, financing instruments, multinational operations, federal laws that impact big business, legal exposure, and so on.

Reports from publicly owned companies

Around 10,000 corporations in the United States are publicly owned, and their stock shares are traded on the New York Stock Exchange, NASDAQ, or other electronic stock markets. Publicly owned companies must file annual financial reports with the SEC — the federal agency that makes and enforces the rules for trading in securities (stocks and bonds). These filings are available to the public on the SEC’s huge database (see the sidebar “Financial reporting on the Internet”).

The annual financial reports of publicly owned corporations include most of the disclosure items I list earlier in the chapter (see the section “Making Sure Disclosure Is Adequate”). As a result, annual reports published by large publicly owned corporations run 30, 40, or 50 pages (or more). As I’ve mentioned before, the large majority of public companies make their annual reports available on their websites. Many public companies also present condensed versions of their financial reports — see the section “Recognizing condensed versions” later in this chapter.

Annual reports from public companies generally are very well done — the quality of the editorial work and graphics is excellent; the color scheme, layout, and design have good eye appeal. But be warned that the volume of detail in their financial reports is overwhelming. (See the next section for advice on dealing with the information overload in annual financial reports.)

Publicly owned businesses live in a fish bowl. When a company goes public with an IPO (initial public offering of stock shares), it gives up a lot of the privacy that a closely held business enjoys. A public company is required to have its annual financial report audited by an independent CPA firm. In doing an audit, the CPA passes judgment on the company’s accounting methods and adequacy of disclosure. The CPA auditor has a heavy responsibility to evaluate the client’s internal controls to prevent financial reporting fraud.

Reports from private businesses

Compared with their public brothers and sisters, private businesses generally issue less impressive annual financial reports. Their primary financial statements with accompanying footnotes are pretty much it for most small private businesses. Often, their financial reports may be printed on plain paper and stapled together. A privately held company may have few stockholders, and typically one or more of the stockholders are active managers of the business, who already know a great deal about the business. I suppose that a private company could email its annual financial report to its lenders and shareowners, although I haven’t seen this.

Up to the present, we have had one set of accounting and financial reporting standards for all businesses, large and small, public and private. However, the blunt truth of the matter is that smaller private companies do not comply fully with all the disclosure requirements that public companies have to comply with. The business and financial communities at large have accepted the “subpar” financial reporting practices of smaller private businesses. Perhaps the recently established Private Company Council (see Chapter 2) will recommend adopting less-demanding disclosure rules by private companies. Or they might leave well enough alone.

A private business may have its financial statements audited by a CPA firm but generally is not required by law to do so. Frankly, CPA auditors cut private businesses a lot of slack regarding disclosure. I don’t entirely disagree with enforcing a lower standard of disclosure for private companies. The stock share market prices of public corporations are extremely important, and full disclosure of information should be made publicly available so that market prices are fairly determined. On the other hand, you could argue that the ownership shares of privately owned businesses are not traded, so there’s no urgent need for a complete package of information.

Dealing with Information Overload

As a general rule, the larger a business, the longer its annual financial report. I’ve seen annual financial reports of small, privately owned businesses that you could read in 30 minutes to an hour. In contrast, the annual reports of large, publicly owned business corporations are typically 30, 40, or 50 pages (or more). You would need two hours to do a quick read of the entire annual financial report, without trying to digest its details. My comments in this section refer to the typical annual financial report of a large public company.

Browsing based on your interests

How do investors in a business deal with the information overload of annual financial reports? Very few persons take the time to plow through every sentence, every word, every detail, and every number on every page — except for those professional accountants, lawyers, and auditors directly involved in the preparation and review of the financial report. It’s hard to say how most managers, investors, creditors, and others interested in annual financial reports go about dealing with the massive amount of information — very little research has been done on this subject. But I have some observations to share with you.

Annual financial reports are designed for archival purposes, not for a quick read. Instead of addressing the needs of investors and others who want to know about the profit performance and financial condition of the business but have only a limited amount of time, accountants produce an annual financial report that is a voluminous financial history of the business. Accountants leave it to the users of annual reports to extract the main points. Financial statement readers use certain key ratios and other tests to get a feel for the financial performance and position of the business. (Chapters 10 and 16 explain how readers of financial reports get a fix on the financial performance and position of a business.)

Recognizing condensed versions

Typically, these summaries — called condensed financial statements — do not provide footnotes or the other disclosures that are included in the complete and comprehensive annual financial reports. If you really want to see the official financial report of the organization, you can ask its headquarters to send you a copy (or, for public corporations, you can go to the SEC database — see the earlier sidebar “Financial reporting on the Internet”).

Using other sources of business information

Keep in mind that annual financial reports are only one of several sources of information to owners, creditors, and others who have a financial interest in the business. Annual financial reports, of course, come out only once a year — usually two months or so after the end of the company’s fiscal (accounting) year. You should keep abreast of developments during the year by reading the quarterly reports of the business. Also, I’d advise you to follow the businesses you invest in by reading the financial press and watching TV programs. And it’s a good idea to keep up with blogs about the companies on the Internet, subscribe to newsletters, and so on. Financial reports present the sanitized version of events; they don’t divulge scandals about the business. You have to find out the negative news about a business by the means I just mentioned.