Chapter 13

Accounting for Costs

IN THIS CHAPTER

Measuring costs: The second-most important thing accountants do

Recognizing the different needs for cost information

Determining the right costs for different purposes

Assembling the product cost of manufacturers

Padding profit by producing too many products

You could argue that measuring costs is the second most important thing accountants do, right after measuring profit. In fact, you need to measure costs in order to measure profit. But really, can measuring a cost be very complicated? You just take numbers off a purchase invoice and call it a day, right? Not if your business manufactures the products you sell, that’s for sure! In this chapter, I demonstrate that a cost, any cost, is not as obvious and clear-cut as you may think. Yet, obviously, costs are extremely important to businesses and other organizations.

Consider an example close to home: Suppose you just returned from the grocery store with several items in the bag. What’s the cost of the loaf of bread you bought? Should you include the sales tax? Should you include the cost of gas you used driving to the store? Should you include some amount of depreciation expense on your car? Suppose you returned some aluminum cans for recycling while you were at the grocery store, and you were paid a small amount for the cans. Should you subtract this amount against the total cost of your purchases? Or should you subtract the amount directly against the cost of only the sodas in aluminum cans that you bought? And is cost the before-tax cost? In other words, is your cost equal to the amount of income you had to earn before income tax so that you had enough after-tax income to buy the items? And what about the time you spent shopping? Your time could have been used for other endeavors. I could raise many other such questions, but you get the point.

These questions about the cost of your groceries are interesting (well, to me at least). But you don’t really have to come up with definite answers for such questions in managing your personal financial affairs. Individuals don’t have to keep cost records of their personal expenditures, other than what’s needed for their annual income tax returns. In contrast, businesses must carefully record all their costs correctly so that profit can be determined each period and so that managers have the information they need to make decisions and to make a profit.

Looking down the Road to the Destination of Costs

All businesses that sell products must know their product costs — in other words, the costs of each and every item they sell. Companies that manufacture the products they sell — as opposed to distributors and retailers of products — have many problems in figuring out their product costs. Two examples of manufactured products are a new Cadillac just rolling off the assembly line at General Motors and a copy of my book, Accounting For Dummies, 6th Edition, hot off the printing presses.

Most production (manufacturing) processes are fairly complex, so product cost accounting for manufacturers is fairly complex; every step in the production process has to be tracked carefully from start to finish. Many manufacturing costs cannot be directly matched with particular products; these are called indirect costs. To arrive at the full cost of each product manufactured, accountants devise methods for allocating indirect production costs to specific products. Surprisingly, accounting standards in the United States, called generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), provide little authoritative guidance for measuring the manufacturing costs of products. Therefore, manufacturing businesses have more than a little leeway regarding how to determine their product costs. Even businesses in the same industry — Ford versus General Motors, for example — may use different product cost accounting methods.

Accountants determine many other costs, in addition to product costs:

- The costs of departments, regional distribution centers, and virtually any identifiable organizational unit of the business

- The cost of the retirement plan for the company’s employees (with the help of actuaries)

- The cost of marketing programs and advertising campaigns

- The cost of restructuring the business or the cost of a major recall of products sold by the business, when necessary

A common refrain among accountants is “different costs for different purposes.” True enough, but at its core, cost accounting serves two broad purposes: measuring profit and providing relevant information to managers for planning, control, and decision-making.

The conundrum is that, in spite of the inherent ambiguity in determining costs, we need exact amounts for costs. Managers should understand the choices an accountant has to make in measuring costs. Some cost accounting methods result in conservative profit numbers; other methods boost profit, at least in the short run. Chapter 8 discusses the choices among different accounting methods that produce financial statements with a conservative or liberal hue.

This chapter covers cost concepts and cost measurement methods that apply to all businesses, as well as basic product cost accounting of manufacturers. I discuss how a manufacturer could be fooling around with its production output to manipulate product cost for the purpose of artificially boosting its profit figure. (Service businesses encounter their own problems in allocating their operating costs for assessing the profitability of their separate sales revenue sources.)

Are Costs Really That Important?

Without good cost information, a business operates in the dark. Cost data is needed for the following purposes:

- Setting sales prices: The common method for setting sales prices (known as cost-plus or markup on cost) starts with cost and then adds a certain percentage. If you don’t know exactly how much a product costs, you can’t be as shrewd and competitive in your pricing as you need to be. Even if sales prices are dictated by other forces and not set by managers, managers need to compare sales prices against product costs and other costs that should be matched against each sales revenue source.

- Formulating a legal defense against charges of predatory pricing practices: Many states have laws prohibiting businesses from selling below cost except in certain circumstances. And a business can be sued under federal law for charging artificially low prices intended to drive its competitors out of business. Be prepared to prove that your lower pricing is based on lower costs and not on some illegitimate purpose.

- Measuring gross margin: Investors and managers judge business performance by the bottom-line profit figure. This profit figure depends on the gross margin figure you get when you subtract your cost of goods sold expense from your sales revenue. Gross margin (also called gross profit) is the first profit line in the income statement (for examples, see Figures 5-1 and 10-1 as well as Figure 13-1 later in this chapter). If gross margin is wrong, bottom-line net income is wrong — no two ways about it. The cost of goods sold expense depends on having correct product costs (see “Assembling the Product Cost of Manufacturers,” later in this chapter).

- Valuing assets: The balance sheet reports cost values for many (though not all) assets. To understand the balance sheet, you should understand the cost basis of its inventory and certain other assets. See Chapter 6 for more about assets and how asset values are reported in the balance sheet (also called the statement of financial condition).

Making optimal choices: You often must choose one alternative over others in making business decisions. The best alternative depends heavily on cost factors, and you have to be careful to distinguish relevant costs from irrelevant costs, as I describe in the later section “Relevant versus irrelevant costs.”

In most situations, the historic book value recorded for a fixed asset is an irrelevant cost. Say book value is $35,000 for a machine used in the manufacturing operations of the business. This is the amount of original cost that has not yet been charged to depreciation expense since it was acquired, and it may seem quite relevant. However, in deciding between keeping the old machine or replacing it with a newer, more efficient machine, the disposable value of the old machine is the relevant amount, not the undepreciated cost balance of the asset.

In most situations, the historic book value recorded for a fixed asset is an irrelevant cost. Say book value is $35,000 for a machine used in the manufacturing operations of the business. This is the amount of original cost that has not yet been charged to depreciation expense since it was acquired, and it may seem quite relevant. However, in deciding between keeping the old machine or replacing it with a newer, more efficient machine, the disposable value of the old machine is the relevant amount, not the undepreciated cost balance of the asset.Suppose the old machine has an estimated $20,000 salvage value at this time; this is the relevant cost for the alternative of keeping it for use in the future — not the $35,000 book value that hasn’t been depreciated yet. To keep using it, the business forgoes the $20,000 it could get by selling the asset, and this $20,000 is the relevant cost in this decision situation. Making decisions involves looking forward at the future cash flows of each alternative — not looking backward at historical-based cost values.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

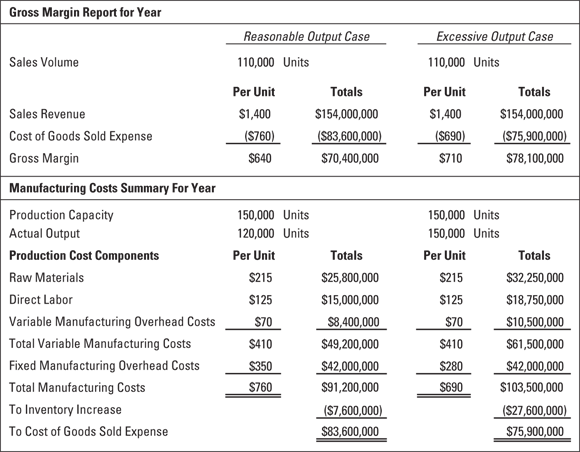

FIGURE 13-1: Manufacturing costs example.

Becoming More Familiar with Costs

This section explains important cost distinctions that managers should understand in making decisions and exercising control. Also, these cost distinctions help managers better appreciate the cost figures that accountants attach to products that are manufactured or purchased by the business.

Retailers (such as Wal-Mart and Costco) purchase products in a condition ready for sale to their customers — although some products have to be removed from shipping containers, and a retailer does a little work making the products presentable for sale and putting the products on display. Manufacturers don’t have it so easy; their product costs have to be “manufactured” in the sense that the accountants have to accumulate various production costs and compute the cost per unit for every product manufactured. I focus on the special cost concerns of manufacturers in the upcoming section “Assembling the Product Cost of Manufacturers.”

Direct versus indirect costs

You might say that the starting point for any sort of cost analysis, and particularly for accounting for the product costs of manufacturers, is to clearly distinguish between direct and indirect costs. Direct costs are easy to match with a process or product, whereas indirect costs are more distant and have to be allocated to a process or product. Here are more details:

- Direct costs can be clearly attributed to one product or product line, one source of sales revenue, one organizational unit of the business, or one specific operation in a process. An example of a direct cost in the book publishing industry is the cost of the paper that a book is printed on; this cost can be squarely attached to one particular step or operation in the book production process.

Indirect costs are far removed from and cannot be naturally attached to specific products, organizational units, or activities. A book publisher’s telephone and Internet bills are costs of doing business but can’t be tied down to just one step in the editorial and production process. The salary of the purchasing officer who selects the paper for all the books is another example of a cost that is indirect to the production of particular books.

Each business must determine methods of allocating indirect costs to different products, sources of sales revenue, revenue and cost centers, and other organizational units. Most allocation methods are far from perfect and, in the final analysis, end up being arbitrary to one degree or another. Business managers should always keep an eye on the allocation methods used for indirect costs and take the cost figures produced by these methods with a grain of salt. If I were called in as an expert witness in a court trial involving costs, the first thing I’d do is critically analyze the allocation methods used by the business for its indirect costs. If I were on the side of the defendant, I’d do my best to defend the allocation methods. If I were on the side of the plaintiff, I’d do my best to discredit the allocation methods — there are always grounds for criticism.

Each business must determine methods of allocating indirect costs to different products, sources of sales revenue, revenue and cost centers, and other organizational units. Most allocation methods are far from perfect and, in the final analysis, end up being arbitrary to one degree or another. Business managers should always keep an eye on the allocation methods used for indirect costs and take the cost figures produced by these methods with a grain of salt. If I were called in as an expert witness in a court trial involving costs, the first thing I’d do is critically analyze the allocation methods used by the business for its indirect costs. If I were on the side of the defendant, I’d do my best to defend the allocation methods. If I were on the side of the plaintiff, I’d do my best to discredit the allocation methods — there are always grounds for criticism.

As I drove from Denver to San Diego (and back again) to work with my coauthor and son, Tage, on our book How to Read a Financial Report, 8th Edition (Wiley), the cost of filling the gas tank was a direct cost of making the trip. The annual auto license plate fee that I pay to the state of Colorado was an indirect cost of the trip, although that fee is a direct cost of having the car available during the year. Determining cost gets a little complicated, doesn’t it?

Fixed versus variable costs

If your business sells 100 more units of a certain item, some of your costs increase accordingly, but others don’t budge one bit. This distinction between variable and fixed costs is crucial:

- Variable costs: Variable costs increase and decrease in proportion to changes in sales or production level. Variable costs generally remain the same per unit of product or per unit of activity. Manufacturing or selling additional units causes variable costs to increase in concert. Manufacturing or selling fewer units results in variable costs going down in concert.

- Fixed costs: Fixed costs remain the same over a relatively broad range of sales volume or production output. Fixed costs are like a dead weight on the business. Its total fixed costs for the period are a hurdle it must overcome by selling enough units at high enough margins per unit in order to avoid a loss and move into the profit zone. (Chapter 12 explains the breakeven point, which is the level of sales needed to generate enough margin to cover fixed costs for the period.)

Note: The distinction between variable and fixed costs is at the heart of understanding, analyzing, and budgeting profit, which I explain in Chapter 14.

Relevant versus irrelevant costs

Not every cost is important to every decision a manager needs to make — hence the distinction between relevant and irrelevant costs:

- Relevant costs are costs that should be considered and included in your analysis when deciding on a future course of action. Relevant costs are future costs — costs that you would incur or bring upon yourself depending on which course of action you take. For example, say that you want to increase the number of books that your business produces next year in order to increase your sales revenue, but the cost of paper has just shot up. Should you take the cost of paper into consideration? Absolutely — that cost will affect your bottom-line profit and may negate any increase in sales volume that you experience (unless you increase the sales price). The cost of paper is a relevant cost.

- Irrelevant (or sunk) costs are costs that should be disregarded when deciding on a future course of action; if brought into the analysis, these costs could cause you to make the wrong decision. An irrelevant cost is a vestige of the past — that money is gone. For this reason, irrelevant costs are also called sunk costs. For example, suppose that your supervisor tells you to expect a slew of new hires next week. All your staff members use computers now, but you have a bunch of typewriters gathering dust in the supply room. Should you consider the cost paid for those typewriters in your decision to buy computers for all the new hires? Absolutely not — that cost should have been written off and is no match for the cost you’d pay in productivity (and morale) for new employees who are forced to use typewriters.

Furthermore, keep in mind that fixed costs can provide a useful gauge of a business’s capacity — how much building space it has, how many machine-hours are available for use, how many hours of labor can be worked, and so on. Managers have to figure out the best way to utilize these capacities. For example, suppose your retail business pays an annual building rent of $200,000, which is a fixed cost (unless the rental contract with the landlord also has a rent escalation clause based on your sales revenue). The rent, which gives the business the legal right to occupy the building, provides 15,000 square feet of retail and storage space. You should figure out which sales mix of products will generate the highest total margin — equal to total sales revenue less total variable costs of making the sales, including the costs of the goods sold and all variable costs driven by sales revenue and sales volume.

Actual, budgeted, and standard costs

The actual costs a business incurs may differ (though we hope not too unfavorably) from its budgeted and standard costs:

- Actual costs: Actual costs are based on actual transactions and operations during the period just ended, or going back to earlier periods. Financial statement accounting is mainly (though not entirely) based on a business’s actual transactions and operations; the basic approach to determining annual profit is to record the financial effects of actual transactions and allocate the historical costs to the periods benefited by the costs. But keep in mind that accountants can use more than one method for recording actual costs. Your actual cost may be a little (or a lot) different from my actual cost.

- Budgeted costs: These are future costs, for transactions and operations expected to take place over the coming period, based on forecasts and established goals. Fixed costs are budgeted differently from variable costs. For example, if sales volume is forecast to increase by 10 percent, variable costs will definitely increase accordingly, but fixed costs may or may not need to be increased to accommodate the volume increase. In Chapter 14, I explain the budgeting process and budgeted financial statements.

- Standard costs: Standard costs are costs, primarily in the area of manufacturing, that are carefully engineered based on a detailed analysis of operations and forecast costs for each component or step in an operation. Developing standard costs for variable production costs is relatively straightforward because most are direct costs. In contrast, most fixed costs are indirect, and standard costs for fixed costs are necessarily based on more arbitrary methods (see “Direct versus indirect costs,” earlier in this chapter). Note: Some variable costs are indirect and have to be allocated to specific products in order to come up with a full (total) standard cost of the product.

Product versus period costs

Some costs are linked to particular products, and others are not:

Product costs are attached directly or allocated to particular products. The cost is recorded in the inventory asset account and stays in that asset account until the product is sold, at which time the cost goes into the cost of goods sold expense account. (See Chapters 5 and 6 for more about these accounts; also, see Chapter 8 for alternative methods for selecting which product costs are first charged to the cost of goods sold expense.)

For example, the cost of a new Ford Taurus sitting on a car dealer’s showroom floor is a product cost. The dealer keeps the cost in the inventory asset account until you buy the car, at which point the dealer charges the cost to the cost of goods sold expense.

- Period costs are not attached to particular products. These costs do not spend time in the “waiting room” of inventory. Period costs are recorded as expenses immediately; unlike product costs, period costs don’t pass through the inventory account first. Advertising costs, for example, are accounted for as period costs and are recorded immediately in an expense account. Also, research and development costs are treated as period costs (with some exceptions).

Separating product costs and period costs is particularly important for manufacturing businesses, as I explain in the next section.

Assembling the Product Cost of Manufacturers

Businesses that manufacture products have several cost problems to deal with that retailers and distributors don’t have. I use the term manufacture in the broadest sense: Automobile makers assemble cars, beer companies brew beer, automobile gasoline companies refine oil, DuPont makes products through chemical synthesis, and so on. Retailers (also called merchandisers) and distributors, on the other hand, buy products in a condition ready for resale to the end consumer. For example, Levi Strauss manufactures clothing, and several retailers buy from Levi Strauss and sell the clothes to the public. This section describes costs unique to manufacturers.

Minding manufacturing costs

Manufacturing costs consist of four basic types:

- Raw materials (also called direct materials) are what a manufacturer buys from other companies to use in the production of its own products. For example, General Motors buys tires from Goodyear (or other tire manufacturers) that then become part of GM’s cars.

- Direct labor consists of those employees who work on the production line.

- Variable overhead is indirect production costs that increase or decrease as the quantity produced increases or decreases. An example is the cost of electricity that runs the production equipment. Generally, you pay for the electricity for the whole plant, not machine by machine, so you can’t attach this cost to one particular part of the process. When you increase or decrease the use of those machines, the electricity cost increases or decreases accordingly. (In contrast, the monthly utility bill for a company’s office and sales space probably is fixed for all practical purposes.)

- Fixed overhead is indirect production costs that do not increase or decrease as the quantity produced increases or decreases. These fixed costs remain the same over a fairly broad range of production output levels (see “Fixed versus variable costs,” earlier in this chapter). Here are three significant examples of fixed manufacturing costs:

- Salaries for certain production employees who don’t work directly on the production line, such as vice presidents, safety inspectors, security guards, accountants, and shipping and receiving workers

- Depreciation of production buildings, equipment, and other manufacturing fixed assets

- Occupancy costs, such as building insurance, property taxes, and heating and lighting charges

Figure 13-1 presents a gross profit report for a business that manufactures just one product. For now, limit your attention to the left side of the report, which lists sales volume, sales revenue, cost of goods sold expense, the four types of manufacturing costs (just discussed), and how total manufacturing costs end up either in cost of goods sold expense or in the increase to inventory. Manufacturing costs are shown both on the total basis for the year and per unit. First, I explain the numbers under the column headed “Reasonable Output Case.”

The $760 product cost equals manufacturing costs per unit. A business may manufacture 100 or 1,000 different products, or even more, and it must compile a summary of manufacturing costs and production output and determine the product cost of every product. To keep the example easy to follow (but still realistic), Figure 13-1 presents a one-product manufacturer. The multi-product manufacturer has additional accounting problems, but I can’t provide that level of detail here. This example exposes the fundamental accounting problems and methods of all manufacturers.

Notice in particular that the company’s cost of goods sold expense is based on the $760 product cost (or total manufacturing costs per unit). This product cost is determined from the company’s manufacturing costs and production output for the period. Product cost includes both the variable costs of manufacture and a calculated amount based on total fixed manufacturing costs for the period divided by total production output for the period.

Classifying costs properly

Two vexing issues rear their ugly heads in determining product cost for a manufacturer:

Drawing a bright line between manufacturing costs and nonmanufacturing operating costs: The key difference here is that manufacturing costs are categorized as product costs, whereas nonmanufacturing operating costs are categorized as period costs (refer to “Product versus period costs,” earlier in this chapter). In calculating product costs, you include only manufacturing costs and not other costs. Remember that period costs are recorded right away as expenses. Here are some examples of each type of cost:

- Wages paid to production line workers are a clear-cut example of a manufacturing (that is, a product cost) component.

- Salaries paid to salespeople are a marketing cost and are not part of product cost; marketing costs are treated as period costs, which means they’re recorded as an expense of the period.

- Depreciation on production equipment is a manufacturing cost, but depreciation on the warehouse in which products are stored after being manufactured is a period cost.

- Moving the raw materials and partially completed products through the production process is a manufacturing cost, but transporting the finished products from the warehouse to customers is a period cost.

The accumulation of direct and indirect production costs starts at the beginning of the manufacturing process and stops at the end of the production line. In other words, product cost stops at the end of the production line — every cost up to that point should be included as a manufacturing cost.

If you misclassify some manufacturing costs as operating costs (nonmanufacturing expenses), your product cost calculation will be too low (see the following section, “Calculating product cost”). Also, the Internal Revenue Service may come knocking at your door if it suspects that you deliberately (or even innocently) misclassified manufacturing costs as nonmanufacturing costs in order to minimize your taxable income.

If you misclassify some manufacturing costs as operating costs (nonmanufacturing expenses), your product cost calculation will be too low (see the following section, “Calculating product cost”). Also, the Internal Revenue Service may come knocking at your door if it suspects that you deliberately (or even innocently) misclassified manufacturing costs as nonmanufacturing costs in order to minimize your taxable income. Allocating indirect costs among different products: Indirect manufacturing costs must be allocated among the products produced during the period. The full product cost includes both direct and indirect manufacturing costs. Creating a completely satisfactory allocation method is difficult; the process ends up being somewhat arbitrary, but it must be done to determine product cost. Managers should understand how indirect manufacturing costs are allocated among products (and, for that matter, how indirect nonmanufacturing costs are allocated among organizational units). Managers should also keep in mind that every allocation method is arbitrary and that a different allocation method may be just as convincing.

Allocating indirect costs among different products: Indirect manufacturing costs must be allocated among the products produced during the period. The full product cost includes both direct and indirect manufacturing costs. Creating a completely satisfactory allocation method is difficult; the process ends up being somewhat arbitrary, but it must be done to determine product cost. Managers should understand how indirect manufacturing costs are allocated among products (and, for that matter, how indirect nonmanufacturing costs are allocated among organizational units). Managers should also keep in mind that every allocation method is arbitrary and that a different allocation method may be just as convincing.

Calculating product cost

The basic calculation of product cost is as follows for the reasonable output case in Figure 13-1:

In our example, the business manufactured 120,000 units and sold 110,000 units during the year, which is reasonable and not atypical, and its product cost per unit is $760. The 110,000 total units sold during the year is multiplied by the $760 product cost to compute the $83.6 million cost of goods sold expense, which is deducted against the company’s revenue from selling 110,000 units during the year. The company’s total manufacturing costs for the year were $91.2 million, which is $7.6 million more than the cost of goods sold expense. The remainder of the total annual manufacturing costs is recorded as an increase in the company’s inventory asset account, to recognize that 10,000 units manufactured this year are awaiting sale in the future. In Figure 13-1, note that the $760 product cost per unit is applied both to the 110,000 units sold and to the 10,000 units added to inventory.

Note: The product cost per unit for our example business is determined for the entire year. In actual practice, manufacturers calculate their product costs monthly or quarterly. The computation process is the same, but the frequency of doing the computation varies from business to business. Product costs likely will vary each successive period the costs are determined. Because the product costs vary from period to period, the business must choose which cost of goods sold and inventory cost method to use. (If product cost happened to remain absolutely flat and constant period to period, the different methods would yield the same results.) Chapter 8 explains the alternative accounting methods for determining cost of goods sold expense and inventory cost value.

Examining fixed manufacturing costs and production capacity

Product cost consists of two distinct components: variable manufacturing costs and fixed manufacturing costs. In Figure 13-1, note that the company’s variable manufacturing costs are $410 per unit and its fixed manufacturing costs are $350 per unit in the reasonable output case. Now, what if the business had manufactured ten more units? Its total variable manufacturing costs would have been $4,100 higher. The actual number of units produced drives variable costs, so even one more unit would have caused the variable costs to increase. But the company’s total fixed costs would have been the same if it had produced ten more units — or 10,000 more units, for that matter. Variable manufacturing costs are bought on a per-unit basis, as it were, whereas fixed manufacturing costs are bought in bulk for the whole period.

The burden rate

The fixed-cost component of product cost is called the burden rate. In our manufacturing example, the burden rate is computed as follows for the reasonable output case (see Figure 13-1 for the data):

Note that the burden rate depends on the number divided into the total fixed manufacturing costs for the period — that is, it depends on the production output for the period.

Now, here’s an important twist on my example: Suppose the company had manufactured only 110,000 units during the period — equal exactly to the quantity sold during the year. Its variable manufacturing cost per unit would have been the same, or $410 per unit. But its burden rate would have been $381.82 per unit (computed by dividing the $42 million total fixed manufacturing costs by the 110,000 units production output). Each unit sold, therefore, would have cost $31.82 more than in the Figure 13-1 example simply because the company produced fewer units. The company would have fewer units of output over which to spread its fixed manufacturing costs. The burden rate is $381.82 at the 110,000 output level but only $350 at the 120,000 output level, or $31.82 lower.

If only 110,000 units were produced, the company’s product cost would have been $791.82 ($410 variable costs plus the $381.82 burden rate). The company’s cost of goods sold, therefore, would have been $3.5 million higher for the year ($31.82 higher product cost × 110,000 units sold). This rather significant increase in its cost of goods sold expense is caused by the company’s producing fewer units, even though it produced all the units that it needed for sales during the year. The same total amount of fixed manufacturing costs is spread over fewer units of production output.

Idle capacity

The production capacity of the business example in Figure 13-1 is 150,000 units for the year. However, this business produced only 120,000 units during the year, which is 30,000 units fewer than it could have. In other words, it operated at 80 percent of production capacity, which results in 20 percent idle capacity:

This rate of idle capacity isn’t unusual — the average U.S. manufacturing plant normally operates at 80 to 85 percent of its production capacity.

The effects of increasing inventory

Look back at the numbers shown in Figure 13-1 for the reasonable output case: The company’s cost of goods sold benefited from the fact that the company produced 10,000 more units than it sold during the year. These 10,000 units absorbed $3.5 million of its total fixed manufacturing costs for the year, and until the units are sold, this $3.5 million stays in the inventory asset account (along with the variable manufacturing costs, of course). It’s entirely possible that the higher production level was justified — to have more units on hand for sales growth next year. But production output can get out of hand, as I discuss in the next section, “Puffing Profit by Excessive Production.”

Managers (and investors as well) should understand the inventory increase effects caused by manufacturing more units than are sold during the year. In the example shown in Figure 13-1, the cost of goods sold expense escaped $3.5 million of fixed manufacturing costs because the company produced 10,000 more units than it sold during the year, thus pushing down the burden rate. The company’s cost of goods sold expense would have been $3.5 million higher if it had produced just the number of units it sold during the year. The lower output level would have increased cost of goods sold expense and would have caused a $3.5 million drop in gross margin.

Puffing Profit by Excessive Production

You need to judge whether an inventory increase is justified. Be aware that an unjustified increase may be evidence of profit manipulation or just good old-fashioned management bungling. Either way, the day of reckoning will come when the products are sold and the cost of inventory becomes cost of goods sold expense or the excess inventory becomes obsolete and can’t be sold.

Shifting fixed manufacturing costs to the future

The business represented in Figure 13-1 manufactured 10,000 more units than it sold during the year — see the reasonable output case in the left columns. This isn’t unusual. In many situations, a manufacturer produces more units than are sold in the period. It’s hard to match production output exactly to sales for the period — unless the business produces the exact number of units ordered by its customers. Anyway, the situation in Figure 13-1 in the reasonable output case isn’t unusual and wouldn’t raise any eyebrows (well, unless the company already had a large inventory of products at the start of the year and didn’t need any more).

With variable manufacturing costs at $410 per unit, the business expended $4.1 million more in variable manufacturing costs than it would have if it had produced only the 110,000 units needed for its sales volume. In other words, if the business had produced 10,000 fewer units, its variable manufacturing costs would have been $4.1 million less — that’s the nature of variable costs. In contrast, if the company had manufactured 10,000 fewer units, its fixed manufacturing costs wouldn’t have been any less — that’s the nature of fixed costs.

Of its $42 million total fixed manufacturing costs for the year, only $38.5 million ended up in the cost of goods sold expense for the year ($350 burden rate × 110,000 units sold). The other $3.5 million ended up in the inventory asset account ($350 burden rate × 10,000 units inventory increase). The $3.5 million of fixed manufacturing costs that are absorbed by inventory is shifted to the future. This amount won’t be expensed (charged to cost of goods sold expense) until the products are sold sometime in the future.

In the example shown under the reasonable output case in Figure 13-1, the 10,000-unit increase of inventory includes $3,500,000 of the company’s total fixed manufacturing costs for the year:

Are you comfortable with this effect? The $3,500,000 escapes being charged to cost of goods expense for the time being. It sits in inventory until the products are sold in a later period. This results from using the full cost (absorption) accounting method for fixed manufacturing overhead costs. Now, it may occur to you that an unscrupulous manager could take advantage of this effect to manipulate gross profit for the period.

Let me be very clear here: I’m not suggesting any hanky-panky in the example shown in Figure 13-1. Producing 10,000 more units than sales volume during the year looks — on the face of it — to be reasonable and not out of the ordinary. Yet at the same time, it’s naïve to ignore that the business did help its pretax profit to the amount of $3.5 million by producing 10,000 more units than it sold. If the business had produced only 110,000 units, equal to its sales volume for the year, all its fixed manufacturing costs for the year would have gone into cost of goods sold expense. The expense would have been $3.5 million higher, and operating earnings would have been that much lower.

Cranking up production output

Now let’s consider a more suspicious example. Suppose that the business manufactured 150,000 units during the year and increased its inventory by 40,000 units. It may be a legitimate move if the business is anticipating a big jump in sales next year. On the other hand, an inventory increase of 40,000 units in a year in which only 110,000 units were sold may be the result of a serious overproduction mistake, and the larger inventory may not be needed next year.

Figure 13-1 also shows what happens to production costs and — more importantly — what happens to the profit at the higher production output level. See the columns under the excessive output case in Figure 13-1. The additional 30,000 units (over and above the 120,000 units manufactured by the business in the reasonable output case) cost $410 per unit of variable manufacturing costs. (The precise cost may be a little higher than $410 per unit because as you start crowding production capacity, some variable costs per unit may increase a little.) The business would need $12.3 million more for the additional 30,000 units of production output:

Again, the company’s fixed manufacturing costs would not have increased, given the nature of fixed costs. Fixed costs stay put until capacity is hit. Sales volume, in this scenario, also remains the same.

But check out the business’s gross margin: $78.1 million, compared with $70.4 million in the reasonable output case — a $7.7 million higher amount, even though sales volume and sales prices remain the same. Whoa! What’s going on here? How can cost of goods sold expense be less? The business sells 110,000 units in both scenarios. And variable manufacturing costs are $410 per unit in both cases.

The culprit is the burden-rate component of product cost. In the reasonable output case, total fixed manufacturing costs are spread over 120,000 units of output, giving a $350 burden rate per unit. In the excessive output case, total fixed manufacturing costs are spread over 150,000 units of output, giving a much lower $280 burden rate, or $70 per unit less. The $70 lower burden rate multiplied by the 110,000 units sold results in a $7.7 million lower cost of goods sold expense for the period, a higher pretax profit of the same amount, and a much improved bottom-line net income.