Chapter 2

Toeing the Straight Line: Linear Equations

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Isolating values of x in linear equations

Isolating values of x in linear equations

![]() Comparing variable values by using inequalities

Comparing variable values by using inequalities

![]() Assessing absolute value in equations and inequalities

Assessing absolute value in equations and inequalities

The term linear has the word line buried in it, and the obvious connection is that you can graph many linear equations as lines. But linear expressions can come in many types of packages, not just equations of lines. Add an interesting operation or two, put several first-degree terms together, throw in a funny connective, and you can construct all sorts of creative mathematical challenges. In this chapter, you find out how to deal with linear equations, what to do with the answers in linear inequalities, and how to rewrite linear absolute value equations and inequalities so that you can solve them.

Linear Equations: Handling the First Degree

Linear equations feature variables that reach only the first degree, meaning that the highest power of any variable you solve for is one. The general form of a linear equation with one variable is

In this equation, the one variable is the x. The a, b, and c are coefficients and constants. (If you go to Chapter 12, you can see linear equations with two or three variables.) But, no matter how many variables you see, the common theme to linear equations is that each variable has only one solution or value that works in the equation.

The graph of the single solution of a linear equation, if you really want to graph it, is one point on the number line — the answer to the equation. When you up the ante to two variables in a linear equation, the graph of all the solutions (there are infinitely many) is a straight line. Any point on the line is a solution. Three variable solutions means you have a plane — a flat surface.

Tackling basic linear equations

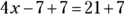

For example, you solve the equation ![]() by adding 7 to each side of the equation, to isolate the variable and the multiplier, and then dividing each side by 4, to leave the variable on its own:

by adding 7 to each side of the equation, to isolate the variable and the multiplier, and then dividing each side by 4, to leave the variable on its own:

becomes

becomes

- giving you

.

.

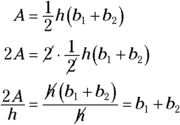

When a linear equation has grouping symbols such as parentheses, brackets, or braces, you deal with any distributing across and simplifying within the grouping symbols before you isolate the variable. For instance, to solve the equation ![]() , you first distribute the 3 and –4 inside the brackets:

, you first distribute the 3 and –4 inside the brackets:

You then combine the terms that combine and distribute the negative sign ![]() in front of the bracket; it’s like multiplying through by

in front of the bracket; it’s like multiplying through by ![]() :

:

Simplify again, and you can solve for x:

To check your answer from the previous example problem, replace every x in the original equation with ![]() . If you do so, you get a true statement. In this case, you get

. If you do so, you get a true statement. In this case, you get ![]() . The solution

. The solution ![]() is the only answer that works — focusing your work on just one answer is what’s nice about linear equations.

is the only answer that works — focusing your work on just one answer is what’s nice about linear equations.

Clearing out fractions

The problem with fractions, like cats, is that they aren’t particularly easy to deal with. They always insist on having their own way — in the form of common denominators before you can add or subtract. (Or, with cats, they get hissy.) And division? Don’t get me started!

To solve ![]() , for example, you multiply each term in the equation by 70, which is the least common denominator (also known as the least common multiple) for fractions with the denominators 5, 7, and 2:

, for example, you multiply each term in the equation by 70, which is the least common denominator (also known as the least common multiple) for fractions with the denominators 5, 7, and 2:

Now you distribute the reduced numbers over each parenthesis, combine the like terms, and solve for x:

Isolating different unknowns

When you see only one variable in an equation, you have a pretty clear idea what you’re solving for. When you have an equation like ![]() or

or ![]() , you identify the one variable and start solving for it.

, you identify the one variable and start solving for it.

Life isn’t always as easy as one-variable equations, however. Being able to solve an equation for some variable when it contains more than one unknown can be helpful in many situations. If you’re repeating a task over and over — such as trying different widths of gardens or diameters of pools to find the best size — you can solve for one of the variables in the equation in terms of the others.

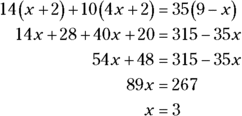

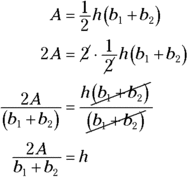

The equation ![]() for example, is the formula you use to find the area of a trapezoid. The letter A represents area, h stands for height (the distance between the two parallel bases), and the two b’s are the two parallel sides called the bases of the trapezoid.

for example, is the formula you use to find the area of a trapezoid. The letter A represents area, h stands for height (the distance between the two parallel bases), and the two b’s are the two parallel sides called the bases of the trapezoid.

If you want to construct a trapezoid that has a set area, you need to figure out what dimensions give you that area. You’ll find it easier to do the many computations if you solve for one of the components of the formula first — for h, ![]() , or

, or ![]() .

.

To solve for h in terms of the rest of the unknowns or letters, you multiply each side by two, which clears out the fraction, and then divide by the entire expression in the parentheses:

You can also solve for ![]() , the measure of the second base of the trapezoid. To do so, you multiply each side of the equation by two, and then divide each side by h.

, the measure of the second base of the trapezoid. To do so, you multiply each side of the equation by two, and then divide each side by h.

Next, subtract ![]() from each side of the equation.

from each side of the equation.

Linear Inequalities: Algebraic Relationship Therapy

Equations — statements with equal signs — are one type of relationship or comparison between things; they say that terms, expressions, or other entities are exactly the same. An inequality is a bit less precise. Algebraic inequalities show relationships between two numbers, a number and an expression, or between two expressions. In other words, you use inequalities for comparisons.

Inequalities in algebra are less than ![]() , greater than

, greater than ![]() , less than or equal to

, less than or equal to ![]() , and greater than or equal to

, and greater than or equal to ![]() . A linear equation has only one solution, but a linear inequality has an infinite number of solutions. When you write

. A linear equation has only one solution, but a linear inequality has an infinite number of solutions. When you write ![]() , for example, you can replace x with

, for example, you can replace x with ![]() , and so on, including all the fractions that fall between the integers that work in the inequality.

, and so on, including all the fractions that fall between the integers that work in the inequality.

- If

, then

, then  (adding any number c).

(adding any number c). - If

, then

, then  (subtracting any number c).

(subtracting any number c). - If

, then

, then  (multiplying by any positive number c).

(multiplying by any positive number c). - If

, then

, then  (multiplying by any negative number c).

(multiplying by any negative number c). - If

, then

, then  (dividing by any positive number c).

(dividing by any positive number c). - If

, then

, then  (dividing by any negative number c).

(dividing by any negative number c). - If

, then

, then  (reciprocating fractions).

(reciprocating fractions).

Notice that the direction of the inequality changes only when multiplying or dividing by a negative number or when reciprocating (flipping) fractions.

Solving linear inequalities

To solve a basic linear inequality, you first move all the variable terms to one side of the inequality and the numbers to the other. After you simplify the inequality down to a variable and a number, you can find out what values of the variable will make the inequality into a true statement. For example, to solve ![]() , you add 4x to each side and subtract 4 from each side. The inequality sign stays the same because no multiplication or division by negative numbers is involved. Now you have

, you add 4x to each side and subtract 4 from each side. The inequality sign stays the same because no multiplication or division by negative numbers is involved. Now you have ![]() . Dividing each side by 7 also leaves the sense (direction of the inequality) untouched because 7 is a positive number. Your final solution is

. Dividing each side by 7 also leaves the sense (direction of the inequality) untouched because 7 is a positive number. Your final solution is ![]() . The answer says that any number larger than one can replace the x’s in the original inequality and make the inequality into a true statement.

. The answer says that any number larger than one can replace the x’s in the original inequality and make the inequality into a true statement.

The rules for solving linear equations (see the section “Linear Equations: Handling the First Degree”) also work with inequalities — somewhat. Everything goes smoothly until you try to multiply or divide each side of an inequality by a negative number.

The inequality ![]() , for example, has grouping symbols that you have to deal with. Distribute the 4 and 3 through their respective multipliers to make the inequality into

, for example, has grouping symbols that you have to deal with. Distribute the 4 and 3 through their respective multipliers to make the inequality into ![]() . Simplify the terms on each side to get

. Simplify the terms on each side to get ![]() . Now you put your inequality skills to work. Subtract 6x from each side and add 14 to each side; the inequality becomes

. Now you put your inequality skills to work. Subtract 6x from each side and add 14 to each side; the inequality becomes ![]() . When you divide each side by

. When you divide each side by ![]() , you have to reverse the sense; you get the answer

, you have to reverse the sense; you get the answer ![]() . Only numbers smaller than

. Only numbers smaller than ![]() or exactly equal to

or exactly equal to ![]() work in the original inequality.

work in the original inequality.

Introducing interval notation

You can alleviate the awkwardness of writing answers with inequality notation by using another format called interval notation. You use interval notation extensively in calculus, where you’re constantly looking at different intervals involving the same function. Much of higher mathematics uses interval notation, although I really suspect that book publishers pushed its use because it’s quicker and neater than inequality notation. Interval notation uses parentheses, brackets, commas, and the infinity symbol to bring clarity to the murky inequality waters.

- You order any numbers used in the notation with the smaller number to the left of the larger number.

- You indicate “or equal to” by using a bracket.

- If the solution doesn’t include the end number, you use a parenthesis.

- When the interval doesn’t end (it goes up to positive infinity or down to negative infinity), use

or

or  , whichever is appropriate, and a parenthesis.

, whichever is appropriate, and a parenthesis.

Here are some examples of inequality notation and the corresponding interval notation:

|

is equivalent to |

|

is equivalent to |

|

is equivalent to |

|

is equivalent to |

Notice that the second example has a bracket by the ![]() , because the “greater than or equal to” indicates that you include the

, because the “greater than or equal to” indicates that you include the ![]() also. The same is true of the 4 in the third example. The last example shows you why interval notation can be a problem at times. Taken out of context, how do you know if

also. The same is true of the 4 in the third example. The last example shows you why interval notation can be a problem at times. Taken out of context, how do you know if ![]() represents the interval containing all the numbers between

represents the interval containing all the numbers between ![]() and 7 or if it represents the point

and 7 or if it represents the point ![]() on the coordinate plane? You can’t tell. You consider the context. A problem containing such notation has to give you some sort of hint as to what it’s trying to tell you.

on the coordinate plane? You can’t tell. You consider the context. A problem containing such notation has to give you some sort of hint as to what it’s trying to tell you.

Compounding inequality issues

A compound inequality is an inequality with more than one comparison or inequality symbol — for instance, ![]() . To solve compound inequalities for the value of the variables, you use the same inequality rules (see the intro to this section), and you expand the rules to apply to each section (intervals separated by inequality symbols).

. To solve compound inequalities for the value of the variables, you use the same inequality rules (see the intro to this section), and you expand the rules to apply to each section (intervals separated by inequality symbols).

To solve the inequality ![]() , for example, you add 5 to each of the three sections and then divide each section by 3:

, for example, you add 5 to each of the three sections and then divide each section by 3:

You write the answer, ![]() , in interval notation as

, in interval notation as ![]() .

.

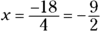

Here’s a more complicated example. You solve the problem ![]() by subtracting 5 from each section and then dividing each section by

by subtracting 5 from each section and then dividing each section by ![]() . Of course, dividing by a negative means that you turn the senses around:

. Of course, dividing by a negative means that you turn the senses around:

You write the answer, ![]() , backward as far as the order of the numbers on the number line; the number

, backward as far as the order of the numbers on the number line; the number ![]() is smaller than 3. To flip the inequality in the opposite direction, you reverse the inequalities, too:

is smaller than 3. To flip the inequality in the opposite direction, you reverse the inequalities, too: ![]() . In interval notation, you write the answer as

. In interval notation, you write the answer as ![]() .

.

Absolute Value: Keeping Everything in Line

When you perform an absolute value operation, you’re not performing surgery at bargain-basement prices; you’re taking a number inserted between the absolute value bars, ![]() , and recording the distance of that number from zero on the number line. For instance

, and recording the distance of that number from zero on the number line. For instance ![]() , because 3 is three units away from zero. On the other hand,

, because 3 is three units away from zero. On the other hand, ![]() , because

, because ![]() is four units away from zero.

is four units away from zero.

Solving absolute value equations

A linear absolute value equation is an equation that takes the form ![]() . You don’t know, taking the equation at face value, if you should change what’s in between the bars to its opposite, because you don’t know if the expression is positive or negative. The sign of the expression inside the absolute value bars all depends on the size and sign of the variable x. To solve an absolute value equation in this linear form, you have to consider both possibilities:

. You don’t know, taking the equation at face value, if you should change what’s in between the bars to its opposite, because you don’t know if the expression is positive or negative. The sign of the expression inside the absolute value bars all depends on the size and sign of the variable x. To solve an absolute value equation in this linear form, you have to consider both possibilities: ![]() may be positive, or it may be negative.

may be positive, or it may be negative.

- For example, to solve the absolute value equation

, you write the two linear equations and solve each for x by subtracting 5 and dividing by 4: If

, you write the two linear equations and solve each for x by subtracting 5 and dividing by 4: If  , then

, then  and

and  .

. - If

, then

, then  and

and  .

.

You have two solutions: 2 and ![]() . Both solutions work when you replace the x in the original equation with their values.

. Both solutions work when you replace the x in the original equation with their values.

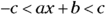

For instance, to solve ![]() , you have to subtract 7 from each side of the equation and then divide each side by 3. Subtracting 7, you have

, you have to subtract 7 from each side of the equation and then divide each side by 3. Subtracting 7, you have ![]() ; then, when you divide by 3, the problem becomes

; then, when you divide by 3, the problem becomes ![]() .

.

Now you can write the two linear equations and solve them for x:

- If

, then

, then  and

and  .

. - If

, then

, then  and

and  .

.

Seeing through absolute value inequality

An absolute value inequality contains both an absolute value, ![]() , and an inequality:

, and an inequality: ![]() , or

, or ![]() . But, then, you knew that was coming.

. But, then, you knew that was coming.

- To solve for x in

you solve

you solve  .

. - To solve for x in

|, you solve both

|, you solve both  and

and  .

.

The first change sandwiches the ![]() between c and its opposite. The second change considers values greater than c (toward positive infinity) and smaller than

between c and its opposite. The second change considers values greater than c (toward positive infinity) and smaller than ![]() (toward negative infinity).

(toward negative infinity).

Sandwiching the values in inequalities

You apply the first rule of solving absolute value inequalities to the inequality ![]() , because of the less-than direction of the inequality. You rewrite the inequality, using the rule for changing the format:

, because of the less-than direction of the inequality. You rewrite the inequality, using the rule for changing the format: ![]() . Next, you add one to each section to isolate the variable; you get the inequality

. Next, you add one to each section to isolate the variable; you get the inequality ![]() . Divide each section by two to get

. Divide each section by two to get ![]() . You can write the solution in interval notation as

. You can write the solution in interval notation as ![]() .

.

Be sure that the absolute value inequality is in the correct format before you apply the rule. The absolute value portion should be alone on its side of the inequality sign. If you have ![]() , for example, you need to add 7 to each side and divide each side by 2 before changing the form:

, for example, you need to add 7 to each side and divide each side by 2 before changing the form:

Adding 7 you get ![]() , and then dividing by 2 the inequality becomes

, and then dividing by 2 the inequality becomes ![]() . Applying the first rule the problem becomes

. Applying the first rule the problem becomes ![]() . Subtracting 5 from each interval gives you

. Subtracting 5 from each interval gives you ![]() . Then, dividing each interval by 3 you have

. Then, dividing each interval by 3 you have ![]() . In interval notation, the answer is written

. In interval notation, the answer is written ![]() .

.

Harnessing inequalities moving in opposite directions

An absolute value inequality with a greater-than sign, such as ![]() , has solutions that go infinitely high to the right and infinitely low to the left on the number line. To solve for the values that work, you rewrite the absolute value, using the rule for greater-than inequalities; you get two completely separate inequalities to solve. The solutions relate to the inequality

, has solutions that go infinitely high to the right and infinitely low to the left on the number line. To solve for the values that work, you rewrite the absolute value, using the rule for greater-than inequalities; you get two completely separate inequalities to solve. The solutions relate to the inequality ![]() or to the inequality

or to the inequality ![]() . Notice that when the sign of the value 11 changes from positive to negative, the inequality symbol switches direction.

. Notice that when the sign of the value 11 changes from positive to negative, the inequality symbol switches direction.

When solving the two inequalities, be sure to remember to switch the sign when you divide by ![]() :

:

Solving ![]() , you first subtract 7 from each side to get

, you first subtract 7 from each side to get ![]() . Dividing by

. Dividing by ![]() , you have

, you have ![]() .

.

Solving ![]() , you subtract 7 to get

, you subtract 7 to get ![]() . Dividing by

. Dividing by ![]() , you have

, you have ![]() . The solution of the absolute value inequality is

. The solution of the absolute value inequality is ![]() or

or ![]() . In interval notation, you write the solution as

. In interval notation, you write the solution as

or

.

Exposing an impossible inequality imposter

The rules for solving absolute value inequalities are relatively straightforward. You change the format of the inequality and solve for the values of the variable that work in the problem. Sometimes, however, amid the flurry of following the rules, an impossible situation works its way in to try to catch you off guard.

For example, say you have to solve the absolute value inequality ![]() . It doesn’t look like such a big deal; you just subtract 8 from each side and then divide each side by 2. The dividing value is positive, so you don’t reverse the sense. After performing the initial steps, you use the rule where you change from an absolute value inequality to an inequality with the variable term sandwiched between inequalities. So, what’s wrong with that? Here are the steps:

. It doesn’t look like such a big deal; you just subtract 8 from each side and then divide each side by 2. The dividing value is positive, so you don’t reverse the sense. After performing the initial steps, you use the rule where you change from an absolute value inequality to an inequality with the variable term sandwiched between inequalities. So, what’s wrong with that? Here are the steps:

Subtracting 8, you get

, and dividing by 2, you get

.

Under the format ![]() , the inequality looks curious. Do you sandwich the variable term between

, the inequality looks curious. Do you sandwich the variable term between ![]() and 1 or between 1 and

and 1 or between 1 and ![]() (the first number on the left, and the second number on the right)? It turns out that neither works. First of all, you can throw out the option of writing

(the first number on the left, and the second number on the right)? It turns out that neither works. First of all, you can throw out the option of writing ![]() . Nothing is bigger than 1 and smaller than

. Nothing is bigger than 1 and smaller than ![]() at the same time. The other version seems, at first, to have possibilities, so you try to solve

at the same time. The other version seems, at first, to have possibilities, so you try to solve ![]() by adding 7 to each interval, giving you

by adding 7 to each interval, giving you ![]() . Dividing each interval by 3, you have

. Dividing each interval by 3, you have ![]() .

.

The solution says that x is a number between 2 and ![]() . If you check the solution by trying a number — say, 2.1 — in the original inequality, you get the following:

. If you check the solution by trying a number — say, 2.1 — in the original inequality, you get the following:

Because 9.4 isn’t less than 6, you know the number 2.1 doesn’t work. You won’t find any number that works. So, you can’t find an answer to this problem. Did you miss a hint of the situation before you dove into all the work? Yes. (Sorry for the tough love!)

You want to save yourself some time and work? You can do that in this case by picking up on the pesky negative number. When you subtract 8 from each side of the original problem and get ![]() , the bells should be ringing and the lights flashing. This statement says that 2 times the absolute value of a number is smaller than

, the bells should be ringing and the lights flashing. This statement says that 2 times the absolute value of a number is smaller than ![]() , which is impossible. Absolute value is either positive or zero — it can’t be negative — so this expression can’t be smaller than

, which is impossible. Absolute value is either positive or zero — it can’t be negative — so this expression can’t be smaller than ![]() . If you caught the situation before doing all the work, hurrah for you! Good eye. Often, though, you can get caught up in the process and not notice the impossibility until the end — when you check your answer.

. If you caught the situation before doing all the work, hurrah for you! Good eye. Often, though, you can get caught up in the process and not notice the impossibility until the end — when you check your answer.

Generally, algebra uses the letters at the end of the alphabet for variables; the letters at the beginning of the alphabet are reserved for coefficients and constants.

Generally, algebra uses the letters at the end of the alphabet for variables; the letters at the beginning of the alphabet are reserved for coefficients and constants. To solve a linear equation, you isolate the variable on one side of the equation. You do so by adding the same number to both sides — or you can subtract, multiply, or divide the same number on both sides.

To solve a linear equation, you isolate the variable on one side of the equation. You do so by adding the same number to both sides — or you can subtract, multiply, or divide the same number on both sides. When distributing a number or negative sign over terms within a grouping symbol, make sure you multiply every term by that value or sign. If you don’t multiply each and every term, the new expression won’t be equivalent to the original.

When distributing a number or negative sign over terms within a grouping symbol, make sure you multiply every term by that value or sign. If you don’t multiply each and every term, the new expression won’t be equivalent to the original. Seriously, though, the best way to deal with linear equations that involve variables tangled up with fractions is to get rid of the fractions. Your game plan is to multiply both sides of the equation by the least common denominator of all the fractions in the equation.

Seriously, though, the best way to deal with linear equations that involve variables tangled up with fractions is to get rid of the fractions. Your game plan is to multiply both sides of the equation by the least common denominator of all the fractions in the equation.