p.147

The History of Audio. It Helps to Know Where You Came From

In This Chapter:

Music no longer has to be stored on reels of tape. Digital audio has taken the worry out of having to physically deliver or ship a master tape of the band’s hit songs at the mercy of the carrier. Even into the mid 1990s, it was common for engineers to travel with their master tapes, or for the masters to be mailed. There was always a chance these masters could be destroyed by the x-ray machine or damaged during transit. Nowadays, a master session is easily transferred over the Internet and mixes can easily be shared online through a variety of methods. This is why it is important to understand different file formats, compression methods, and how audio files such as MP3s, AIFFs, and WAVs affect audio quality.

To fully understand digital audio technology, you need to understand how, when, and why we ended up digitizing audio. For over a century, analog was the only way we recorded and reproduced music. Digital technology opened up recording to the masses. Prior to the introduction of digital technology, most musicians frequented large, professional studios to record their music, because there was no other option. These days, many musicians and engineers have the option of using professional home or project studios to record music.

Many extraordinary people contributed to this modern era of recording. Legendary engineers such as Les Paul, Tom Dowd, and Bill Putnam shaped the audio world as we know it today. Numerous audio advances occurred around World War II as the world at war sought out new communication technologies. Until the 1980s, music was recorded primarily to an analog medium such as lacquer or tape. Although the technology to record music using a computer had been around for more than fifty years, it wasn’t until about twenty years ago that it became commonplace. Currently, many people combine the best of both worlds, recording with both analog and digital equipment.

p.148

AUDIO HISTORY

A Brief History of Recording

Sound was initially recorded to a single track with a single transducer. Early on, it was extremely important to place the one and only transducer in the perfect spot to pick up all the musicians and get a good balance. Since the performance was live it was essential for the musicians to be well rehearsed and to perform at their peak. Eventually, music would be recorded using many mics and recording to one or two tracks. In the 1950s, people like Les Paul started using eight tracks with more mics and began to regularly layer (overdub) tracks. This was really the beginning of modern recording as we know it. Now, music production is much more flexible, allowing engineers to record limitless tracks in their own home with an array of affordable equipment.

Some notable moments in sound and recording:

■ The first method of recording and playing back of sound is credited to Thomas Edison with his invention of the phonograph in 1877.

■ The first flat, double-sided disc, known as a record, was invented by Emile Berliner in 1887. That same year, Berliner also patented the gramophone.

■ The first ten-inch 78 rpm gramophone record was introduced in the early 1900s. The ten-inch disc offered around four minutes’ recording time per side.

■ Stereo recording was patented in 1933 by Alan Blumlein with EMI.

■ The LP (long-playing) record was invented by Columbia Records in 1948. LPs offered around thirty minutes’ recording time per side.

■ The first multi-track recording was developed in Germany in the 1940s; however, the first commercial multi-track recording is credited to Les Paul in 1955.

■ The first seven-inch 45 rpm record was introduced in North America in 1949. The seven-inch single offered around five minutes’ recording time per side.

■ Ampex built the first eight-track multi-track recorder for Les Paul in 1955.

■ Endless loop tape existed decades before the classic eight-track player and cartridge were invented by Bill Lear in 1963.

■ Although Elisha Gray invented the first electronic synthesizer in 1876, Robert Moog introduced the world to the first commercially available synthesizer in 1964.

■ Before transistors, vacuum tubes were the main components in electronics. Today, the transistor is the main component in modern electronics. The transistor has contributed to things becoming smaller, cheaper, and lasting longer. Although the original transistor patent was filed in the mid 1920s, transistors were not commonly used to replace vacuum tubes until the 1960s and 70s.

p.149

■ Cassettes were invented by the Philips Company in 1962, but did not become popular until the late 70s. Cassettes took up less physical space than vinyl records.

■ MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) was developed in the early 80s, which enabled computers and electronic musical devices to communicate with one another.

■ James Russell came up with the basic idea for the Compact Disc (CD) in 1965. Sony Philips further developed the idea and released the first disc in 1979. CDs were introduced to the public in 1982. Just as cassettes replaced vinyl, CDs brought the cassette era to an end.

■ Pro Tools, originally released as “Sound Designer,” was invented in 1984 by two Berkeley students, Evan Brooks and Peter Gotcher. Pro Tools was introduced to the public in 1991 and featured four tracks, costing $6000.

■ The ADAT (Alesis Digital Audio Tape) recorder helped usher in the home project studio by making a compact and affordable digital multi-track tape machine. It was introduced by Alesis in 1992.

■ Although the initial idea for the MP3 was developed in the early 70s to compress audio information, the MP3 wasn’t adopted until about 1997. An MP3 requires less physical storage space than its many predecessors: the vinyl record, cassette, and CD. In fact, it takes almost no physical storage space! Imagine storing 10,000 vinyl records as opposed to storing 10,000 MP3s.

Innovators Who Contributed to Modern Recording

As previously mentioned, Bill Putnam, Les Paul, and Tom Dowd are three of the early pioneers of modern recording. These people introduced the modern recording console, multi-track recording, reverb, tape delay, multiband EQ, the fader, and many other developments now taken for granted.

Bill Putnam

Often referred to as the “father of modern recording.” His company, Universal Recording Electronics Industries (UREI), developed the classic UREI 1176LN compressor, a signal processor that is highly regarded to this day. Putnam is credited with the development of the modern recording console and contributed greatly to the post-World War II commercial recording industry. Along with his good friend Les Paul, Bill helped develop stereophonic recording. He is also credited with developing the echo send and using reverb in a new way. Not only was Bill Putnam a highly sought-after engineer and producer, he was also a studio and record label owner, equipment designer, and musician. Bill Putnam started Universal Recording in Chicago in the 1950s and recorded such artists as Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Hank Williams, Muddy Waters, and Frank Sinatra. He eventually moved his company to California and renamed it United Recording Corp. Bill passed away in 1989 and in 2000 he was awarded a Grammy for Technical Achievement for all his contributions to the recording industry.

p.150

Les Paul (Lester William Polsfuss)

You can’t talk about early recording without mentioning Les Paul. Most people know of Les Paul because of his legendary guitar playing; but many engineers know of Les Paul for his contributions to the recording industry. Although not the first person to incorporate layering tracks, Les Paul is credited with multi-track recording as we know it. Les Paul had already been experimenting with overdubbed recordings on disc before using analog tape. When he received an early Ampex Model 200, he modified the tape recorder by adding additional recording and playback heads, thus creating the world’s first practical tape-based multi-track recording system. This eight-track was referred to as the “Sel-Sync-Octopus,” later to be referred to as just the “Octopus.” Les Paul is also credited with the development of the solid body electric guitar. Many believe that this instrument helped launch rock ’n’ roll.

Tom Dowd

A famous recording engineer and producer for Atlantic Records, Tom worked on the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb before he started his extraordinary career in music production. Tom Dowd was involved in more hit records than George Martin and Phil Spector combined. He recorded Ray Charles, the Allman Brothers, Cream, Lynyrd Skynyrd, the Drifters, the Coasters, Aretha Franklin, the J. Geils Band, Rod Stewart, the Eagles, and Sonny and Cher, to name just a few. He also captured jazz masterpieces by Charlie Parker, Charles Mingus, Thelonius Monk, Ornette Coleman, and John Coltrane. He came up with the idea of a vertical slider (fader) instead of the rotary-type knob used at the time. Like Putnam and Paul, Dowd pushed “stereo” into the mainstream along with advancing multi-track recording. Tom Dowd was also one of the first engineers willing to make the bass line prevalent in modern recordings. Dowd was an incredible musician known for his remarkable people skills and received a well-deserved Grammy Trustees Award for his lifetime achievements in February 2002.

![]() TIP

TIP

Check out the DVD biography of Tom Dowd, Tom Dowd and The Language of Music (2003).

THE PROS AND CONS OF ANALOG

I was working at a professional studio when digital was first introduced in the 1980s. The strong opinions around this new technology spawned a twenty-plus year debate, analog vs. digital. As an audio engineer, I do feel privileged to have started my music production career without a computer. I would encourage every audio enthusiast at some point to at least try recording on an analog four-track or eight-track reel-to-reel. It is a great way to understand signal flow, learn the art of a good punch-in, gain an appreciation for a high-quality performance, and learn to work with a limited number of tracks. That being said, it’s apparent we aren’t going back to the time when a large-format console with a bulky multi-track tape machine once ruled. Digital is the standard today, and because of this many engineers now desire analog gear to warm up, add harmonic distortion, and help provide timeless tones to their projects. Listed below are the pros and cons of analog and digital.

p.151

Pros of Analog

Tonal quality: Proponents of analog often describe it as fat, warm, and easy on the ears.

The soul: Many audiophiles and purists swear by analog and the way that it captures more of the soul of the music.

Transients: An analog recorder softens the transients. Unlike digital audio, analog doesn’t reproduce and record transients as well. Many audio engineers enjoy this because cymbals and other edgy or piercing sounds are toned down and mellowed.

Tape compression: In the digital world, levels can’t go over zero, but with analog it is quite often desired. When the level is pushed on an analog recorder, the signal is saturated on the tape, a desired effect for many.

Holds its value: Quality analog equipment typically holds its value and can easily be resold. This is especially true with classic mics, preamps, and compressors, but is not necessarily the case with tape machines and FX.

Classic: Analog tape provides a classic tone. Especially useful for certain styles of music with more of a roots or organic feel such as classic rock, jazz, folk, bluegrass, blues, surf, indie rock, and some country.

No sampling: With digital audio, samples are taken of the music. Analog means it is analogous to sound. With analog you get all the pieces and not samples.

Cons of Analog

Editing: Although almost any edit can be done in the analog world that can be done in the digital world, editing is destructive and time-consuming. With analog, the tape has to be cut physically and there is no “undo,” there is only “do-over”!

Cumbersome: A typical analog recording setup requires more physical space than most digital setups.

Conversion: Most recordings end up digital anyway (unless you record all analog and press to vinyl), so why not just start with digital? Obviously, you can’t download or upload music in an analog format. It has to be digitized at some point.

p.152

Tape costs: A reel of two-inch tape needed for analog recording costs about $300. A standard 2500-foot reel of tape can record about 16 to 33 minutes of material, depending on the tape speed.

Tape storage: Reels of tape must be stored in a dry, temperature-controlled space. You will need plenty of space to store your new and used reels of tape!

Sound quality: Digital enthusiasts describe analog as noisy and muddy. Many like the clarity that digital audio provides.

![]() TIP

TIP

Check out the music documentary Sound City to see and hear the impact of analog recording (http://buy.soundcitymovie.com).

THE PROS AND CONS OF DIGITAL

Pros of Digital

Editing: The editing capabilities in the digital audio world are undoubtedly the high point. These editing capabilities are non-destructive. Sections of songs can easily be manipulated without damaging the quality of sound. There is an “undo” function.

Efficient: It is much easier for an engineer to flip from one song to another or from one recording to another during a session. With analog tape you may have to change tape reels or wait for the tape to rewind. With digital, a click of the mouse allows you to flip between recorded projects.

Transients: Digital audio reproduces transients accurately. This is one of the reasons why it is known for clarity.

No noise: Tape hiss and extraneous noise will most likely not be a problem in the digital world. You don’t have to worry about recording a hot signal to cover the inherent noise associated with analog tape.

Compact: In the digital world, a full recording setup can literally exist in the palm of your hand. Analog equipment requires more physical space.

Convenient: You can stream your favorite music from any country with online sites like Spotify (www.spotify.com), Napster (www.napster.com), and Pandora (www.pandora.com). You can also store songs, mixes, and full playlists on most wireless phones. It would be very difficult to lug around your favorite 500 albums or cassettes.

Storage capacity and costs: A hard drive or other digital storage device is cheaper and can store hundreds to thousands of hours of recorded material in one place.

Recall: You can recall any previously stored setting of a mix. If the band loves the final mix, but just wants the bass up a dB or two, you can easily open the last mix file and adjust. In the analog world, unless the console is completely automated, you have to make a fresh start. Even then, you have to document every signal processor setting and any other settings that cannot be automatically recalled.

p.153

Demand: People demand audio digitized. Whether it is in the form of an MP3 or a streaming audio file, digital audio is the standard.

Cons of Digital

Tonal quality: Early on, digital audio was very harsh and although it has come a long way, there are engineers who still wish it sounded more like analog. Digital audio has been described as sounding thin and bright with less depth.

Value: Digital equipment is like buying a new car. Once you drive it off the lot, it loses value. It is not lucrative to re-sell outdated software or digital audio components.

Constant updates: Apple is known for issuing regular updates, and this can be an issue if older session files aren’t compatible with these newer updates. Also, software updates aren’t always free and in some cases can be quite costly.

Lossy files: Lossy files throw away “unnecessary” information to condense an audio file’s size. Unfortunately, once you convert an audio file to an MP3, or other lossy format, it cannot be returned to its original audio quality.

It can crash: If audio files are not backed up and the DAW crashes, you could lose everything you have recorded.

COMPUTERS AND AUDIO

Making Music With Computers

Within the last two decades, computers have become an integral part of music composition, performance, and production. Although computers have been used to make music since the 1950s, recent advancements in technology have allowed engineers virtually unlimited control and flexibility when it comes to creating, editing, manipulating, and recording sound.

Musical Instrument Digital Interface, or MIDI, was developed in the early 80s as a data protocol that allows electronic musical instruments, such as a digital synthesizer and drum machine, to control and interact with one another. As computers became increasingly popular, MIDI was integrated to allow computers and electronic musical devices the ability to communicate. Over the past decade, the term MIDI has become synonymous with computer music. Now most commercial audio software has MIDI integration.

In addition to device communication, MIDI can be used internally within computer software to control virtual computer instruments such as software sequencers, drum machines, and synthesizers. Songwriters and composers who use virtual scoring software to create sheet music also use MIDI.

p.154

In many ways, MIDI works much like a music box or the player pianos from the early twentieth century. In this example, the player piano uses a built-in piano roll with notches that trigger the appropriate notes on the piano as the roll is turning. MIDI works in a similar fashion. Let’s take a look at a simple MIDI keyboard controller.

This controller does not make any sound on its own; rather, it connects to the computer and signals to the software which key is being pressed or which knob is being turned. Each key, knob, and button is assigned a unique MIDI number that allows the computer to differentiate which note is being played (pitch), how long the notes are held (envelope), and how hard the key is pressed (velocity).

FIGURE 10.1

FIGURE 10.2

p.155

The information gathered from each key is stored in a MIDI note packet that is sent to the computer whenever a key is pressed. When the computer software receives the note packet, it unpacks and translates the information, assigning the incoming values to a virtual software instrument such as a synthesizer plug-in. The software then plays the appropriate pitch for the correct amount of time, and with the correct velocity. Additional controls on the MIDI keyboard such as knobs, buttons, and faders can be used to control virtual controls on the software instrument.

FIGURE 10.3

In addition to allowing real-time performance, certain music software programs have exclusive MIDI tracks that can record the MIDI information as a sequence, allowing additional editing and arrangement of notes and controller information.

Since the early 80s, MIDI has been the industry-standard protocol for communication between electronic musical devices and computers. However, it has more recently been used to allow computers to control hardware devices in the real world such as lighting grids, video projections, and even musical robotics. Additionally, newer data protocols such as Open Sound Control (OSC) allow faster and more flexible computer/hardware integration utilizing the latest in both Internet and wireless technology.

Computer Choices

If you are just getting into music production it is highly likely that you will be using a computer to create, record, and mix. Here are some considerations when looking for the right computer for your audio production needs:

p.156

Portability: If you want portability you will obviously gravitate toward a laptop. There are some drawbacks to making this decision. First is monitor size. Working on a small screen can be challenging if you plan on doing a lot of editing and mixing. You may need to purchase a larger monitor to use with your laptop. Also, with a laptop there are fewer connections available. You generally get less processing speed for your money. Finally, with some laptops upgrading isn’t always an option.

PC vs. Mac: Most music software works great with both Windows and Mac but a few programs don’t, such as Apple’s Logic or GarageBand (see below for complete list). Some plug-ins and hardware are designed specifically for a PC or a Mac, so make sure your favorite plug-ins or interface will work with your computer choice. Consider choosing the operating system you are most comfortable maneuvering.

Motherboard: The motherboard is the hub of your computer. It determines the speed and amount of RAM available for use. It also dictates the number and type of expansion slots. The motherboard defines the number of buses available as well as their speed. Some “off brand” processors and motherboards will not work with certain DAWs. If you plan on using a particular DAW, research their approved hardware first.

Processing speed and core count: It is especially important to have maximum processing speed if you are producing music entirely in the box. Consider purchasing the fastest, multi-cored CPU you can afford. Also, think about purchasing an external DSP (digital signal processor), which will allow you to process audio in real time without taxing your system.

RAM: The more plug-ins and virtual instruments you plan on using the more RAM you will need. If you can’t afford a lot of RAM, look for a computer with expandable capabilities for future needs. Keep in mind, if you are using a laptop you will likely need a pro to install these upgrades.

Software Choices

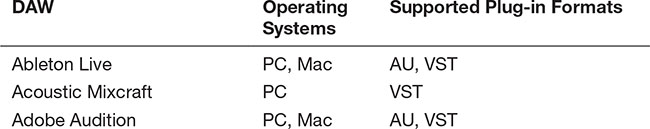

You want to start recording on your computer. With so many options of DAWs, which setup is best for you? Table 10.1 lists some of the most commonly used recording software/programs, supported plug-in formats and associated equipment.

Table 10.1 Commonly used programs and plug-ins

p.157

Scoring Software: Finale, Sibelius

Sequencers: Reason, FL Studio (PC only), Acid Pro (PC only)

VST Plug-ins (Virtual Studio Technology): iZotope, Native Instruments, Sonalksis, Soundtoys, Steinberg, Waves

Advanced Synthesis: NI Reaktor, Max/MSP, C Sound, Supercollider, ChucK

OSC: TouchOSC iPhone App

MIDI Controllers: Korg, M-Audio, AKAI, Roland, Novation, Monome, Livid Instruments, Lemur

Pro Tools is one of the most popular software programs used in professional recording studios. As with anything, people have their views, both good and bad, about this product. Whether you like it or not, knowing a little bit about Pro Tools isn’t going to hurt, especially if you want to be employed in music production. That’s not to say you shouldn’t explore the other software options; in fact, I urge you to find what works best for your project and work flow, and sounds best to you. Many engineers swear by Nuendo, Ableton, and other digital audio software. I have found that once you understand signal flow and other basic audio technology, it is fairly easy to jump from one digital audio software program to another.

The Best of Both Worlds

As you will see in Chapter 14, many professionals use a combination of analog and digital equipment.

Many professionals know that it isn’t a matter of analog versus digital, but picking and choosing the best gear from both worlds. Many studios have Pro Tools, Nuendo, Logic, or other software technology along with an analog option like a two-track or twenty-four-track tape machine to color or warm up a signal. Studios with digital setups often use an analog front end. This front end can include tube preamps, compressors, and analog EQs.

p.158

There will always be people that insist that one recording medium is better than the other. However, many engineers stand somewhere in the middle, combining the best of both worlds and using what works and sounds the best to them, or is appropriate for their particular project.

Don’t forget to check out Chapter 14’s FAQs answered by pros. Here you can find out what a group of select recording engineers think about the future, including their take on Pro Tools, analog, and digital audio.