What is photography?

Basically photography is a combination of visual imagination and design, craft skills, and practical organizing ability. Try not to become absorbed in the craft detail too soon. Begin by putting it into perspective with a broad look at what making photographs is all about. On the one hand there is the machinery and the techniques themselves. On the other you have the variety of approaches to picture making – aiming for results ranging from something objective, factual and precise, to work which is self-expressive and open to interpretation.

Why do you want to take photographs? What is actually involved? What roles do photographs play, relative to other ways of making pictures or expressing information and ideas? And what makes a result good or bad anyway?

One of the first attractions of photography for many people is the lure of the equipment itself. All that ingenious modern technology designed to fit hand and eye – there is great appeal in pressing buttons, clicking precision components into place, and collecting and wearing cameras. Tools are vital, of course, and detailed knowledge about them absorbing and important, but don’t end up shooting photographs just to test out the machinery.

Figure 1.1 Frozen action. This high-speed flash shot of a splash of milk is a factual record. But it can also be enjoyed for its natural design. Photography has revealed something too brief for the human eye alone to see

Another attractive facet is the actual process of photography – the challenge of care and control, and the way this is rewarded by technical excellence and a final object you produced yourself. Results can be judged and enjoyed for their own intrinsic photographic ‘qualities’, such as superb detail, rich tones and colours. The process gives you the means of ‘capturing your seeing’, making pictures from things around you without having to laboriously draw. The camera is a kind of time machine, which freezes any person, place or situation you choose. It seems to give the user power and purpose.

Yet another facet is enjoyment of the visual structuring of photographs. There is real pleasure to be had from designing pictures as such – the ‘geometry’ of lines and shapes, balance of tone, the cropping and framing of scenes – whatever the subject content actually happens to be. So much can be done by a quick change of viewpoint, or choice of a different moment in time.

Perhaps you are drawn into photography mainly because it is a quick, convenient and seemingly truthful way of recording something. All the importance lies in the subject itself, and you want to show objectively what it is, or what is going on. Photography is evidence, identification, a kind of diagram of a happening. The camera is your visual notebook.

The opposite facet of photography is where it is used to manipulate or interpret reality, so that pictures push some ‘angle’ or attitude of your own. You set up situations (as in advertising) or choose to photograph some aspect of an event but not others (as in politically biased news reporting). Photography is a powerful medium of persuasion and propaganda. It has that ring of truth when all the time, in artful hands, it can make any statement the manipulator chooses.

Another reason for taking up photography is that you want a means of personal self-expression. It seems odd that something so apparently objective as photography can be used to express, say, issues of identity, or metaphor and mysticism – describing daydreams that may not be immediately apparent from the subject matter in front of the camera. But we have probably all seen images ‘in’ other things, like reading meanings into flickering flames, shadows or peeling paint. A photograph can intrigue through its posing of questions, keeping the viewer returning to read new things from the image. The way it is presented too may be just as important as the subject matter. Other photographers simply seek out beauty, which they express in their own ‘picturesque’ style, as a conscious work of art.

These are only some of the diverse activities and interests covered by the umbrella term ‘photography’. None are ‘better’ or more important than others. Several will be blended together in the work of a photographer, or any one market for professional photography. Your present enjoyment in producing pictures may be mainly based on technology, art or communication. And what begins as one area of interest can easily develop into another. As a beginner it is helpful to keep an open mind. Provide yourself with a well-rounded ‘foundation course’ by trying to learn something of all these facets, preferably through practice rather than theory alone.

Photography is to do with light forming an image, normally by means of a lens. The image is then permanently recorded either by:

(a) |

chemical means, using film, liquid chemicals and darkroom processes or |

(b) |

digital means, using an electronic sensor, data storage and processing, and print-out via a computer. |

Chemical forms of image recording are long established, steadily improved since the mid nineteenth century. Digital methods have only become practical within the past five years but are rapidly evolving. Photographers increasingly combine the two – shooting on film and then transferring results into digital form for manipulating and print-out.

You don’t need to understand either chemistry or electronics to take good photographs of course, but it is important to have sufficient practical skills to control results and so work with confidence. The following is an outline of the key technical stages you will meet in chemical and in digital forms of photography. Each stage is discussed in detail in later chapters.

Forming and exposing an image

Most aspects of forming an optical image of your subject (in other words concerning the ‘front end’ of the camera) apply to both film and digital photography. Light from the subject of your picture passes through a glass lens, which bends it into a focused (normally miniaturized) image. The lens is at the front of a light-tight box or camera with a light-sensitive surface such as film facing it at the other end. Light is prevented from reaching the film by a shutter until your chosen moment of exposure. The amount of exposure to light is most often controlled by a combination of the time the shutter is open and the diameter of the light beam passing through the lens. The latter is altered by an aperture, like the iris of the eye. Both these controls have a further influence on visual results. Shutter time alters the way movement records blurred or frozen; lens aperture alters the depth of subject that is shown in focus at one time (depth of field).

You need a viewfinder, focusing screen or electronic viewing screen for aiming the camera and composing, and a light measuring device, usually built in, to meter the brightness of each subject. The meter takes into account the light sensitivity of the material on which you are recording the image and reads out or automatically sets an appropriate combination of lens aperture and shutter speed. With knowledge and skill you can override these settings to achieve chosen effects or compensate for conditions which will fool the meter.

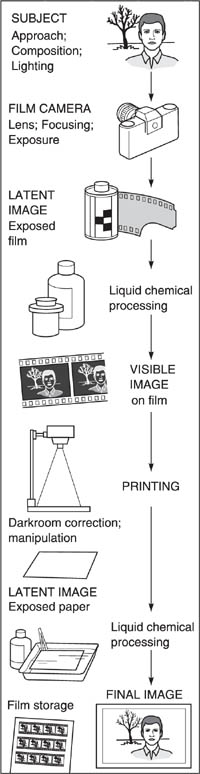

Figure 1.2 Basic route from subject to final photographic image, using film. This calls for liquid chemicals and darkroom facilities

The chemical route

Processing. If you have used a film camera the next stage will be to process your film. A correctly exposed film differs from an unexposed film only at the atomic level – minute chemical changes forming an invisible or ‘latent’ image. Developing chemicals must then act on your film in darkness to amplify the latent image into something much more substantial and permanent in normal light. You apply these chemicals in the form of liquids; each solution has a particular function when used on the appropriate film. With most black and white films, for example, the first chemical solution develops light-struck areas into black silver grains. You follow it with a solution which dissolves (‘fixes’) away the unexposed parts, leaving these areas as clear film. So the result, after washing out by-products and drying, is a black and white negative representing brightest parts of your subject as dark and darkest parts pale grey or transparent.

A similar routine, but with chemically more complex solutions, is used to process colour film into colour negatives. Colour slide film needs more processing stages. First a black and white negative developer is used, then the rest of the film instead of being normally fixed is colour developed to create a positive image in black silver and dyes. You are finally left with a positive, dye-image colour slide.

Printing negatives. The next stage of production is printing, or, more often, enlarging. Your picture on film is set up in a vertical projector called an enlarger. The enlarger lens forms an image, of almost any size you choose, on to light-sensitive photographic paper. During exposure the paper receives more light through clear areas of your film than through the denser parts. The latent image your paper now carries is next processed in chemical solutions broadly similar to the stages needed for film. For example, a sheet of black and white paper is exposed to the black and white film negative, then developed, fixed and washed so it shows a ‘negative of the negative’, which is a positive image – a black and white print. Colour paper after exposure goes through a sequence of colour developing, bleaching and fixing to form a colour negative of a colour negative. Other materials and processes give colour prints from slides.

An important feature of printing (apart from allowing change of image size and running off many copies) is that you can adjust and correct your shot. Unwanted parts near the edges can be cropped off, changing the proportions of the picture. Chosen areas can be made lighter or darker. Working in colour you can use a wide range of enlarger colour filters to ‘fine-tune’ the colour balance of your print, or to create effects. With experience you can even combine parts from several film images into one print, form pictures which are part-positive part-negative, and so on.

Colour and black and white. You have to choose between different types of film for photography in colour or black and white (monochrome). Visually it is much easier to shoot colour than black and white, because the result more closely resembles the way the subject looked in the viewfinder. You must allow for differences between how something looks and how it comes out in a colour photograph, of course (see Chapter 6). But this is generally less difficult than forecasting how subject colours will translate into tones of monochrome. At its best, black and white photography is considered more interpretative and subtle, less crudely lifelike than colour. For this reason it has become a minority enthusiasts’ medium, still important for ‘fine prints’ and gallery shows. Here it readily rubs shoulders with black and white photography of the past.

Colour films, papers and chemical processes are more complex than black and white. This is why it was almost a hundred years after the invention of photography before reliable colour print processes appeared. Even then they were expensive and laborious to use, so that until the 1970s photographers mostly learnt their craft in black and white and worked up to colour. Today practically everyone takes their first pictures in colour. Most of the chemical complexity of colour photography is locked up in the manufacturers’ films, papers, ready-mixed solutions and standardized processing routines. It is mainly in printing that colour remains more demanding than black and white, because of the extra requirements of judging and controlling colour balance (see Advanced Photography). So in the darkroom at least you will find that photography by the chemical route is still best begun in black and white.

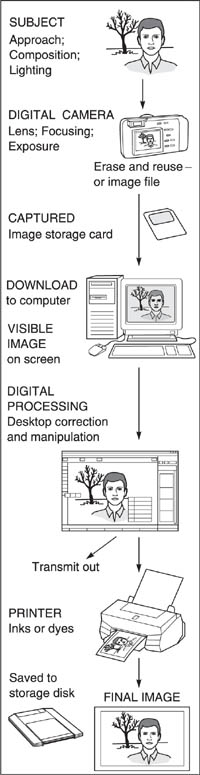

Storing, downloading and processing. If you are using a digital camera the exposed image is recorded on a grid of millions of microscopic size light-sensitive elements. This is known as a CCD (charge-coupled device) located in a fixed but similar position to film within a film camera. Immediately following exposure the CCD reads out its captured picture as a chain of electronic signals called an image file, usually into a small digital storage card slotted into the camera body. Wanted image files are later downloaded from the card or direct from the camera into a computer, where they appear as full-colour pictures on a monitor screen. Unwanted shots are erased. After downloading or erasures you can re-use the card indefinitely for storing new camera pictures.

A software program which has also been loaded into the computer now offers you ‘tools’ and controls alongside the picture to crop, adjust brightness, contrast or colour and many other manipulations. Each one is selected and activated by moving and clicking the computer mouse – changes to the image appear almost immediately on the monitor display.

Printing out. When the on-screen picture looks satisfactory the revised digital file can be fed to a desktop printer – typically an ink-jet type – for full colour print-out on paper. Image files can be ‘saved’ (stored) within the computer’s internal hard disk memory or on a removable disc.

Practical comparisons between making photographs by the chemical (film) route and the digital route appear in detail on pages 96 and 105. You will see that each offers different advantages and trade-offs, and for the time being there are good reasons for combining the best features of each.

Figure 1.3 Basic digital route from subject to final image. No chemicals or darkroom are needed, and camera cards for image storage can be re-used. Images may also be digitalized from results shot on film, via a film scanner or Photo-CD

Technical routines and creative choices

Whether you work by chemical or digital means, photography involves you in two complementary skills.

• |

First, there are set routines where consistency is all important, for example film processing or paper processing, especially in colour, and the disciplines of inputting and saving digital image files. |

• |

Second, there are those stages at which creative decisions must be made, and where a great deal of choice and variation is possible. These include organization of your subject, lighting and camera handling, as well as editing and printing the work. As a photographer you will need to handle and make these decisions yourself, or at least closely direct them. |

With technical knowledge plus practical experience (which comes out of shooting lots of photographs under different conditions) you gradually build up skills that become second nature. It’s like learning to drive. First you have to consciously learn the mechanical handling of a car. Then this side of things becomes so familiar you concentrate more and more on what you want to achieve with the machinery.

Having more confidence about getting results, you find you can spend most time on picture-making problems such as composition, and capturing expressions and actions which differ with every shot and have no routine solutions. However, still keep yourself up-to-date on new processes and equipment as they come along. You need to discover what new visual opportunities they offer.

Technical routines and creative choices give a good foundation for what is perhaps the biggest challenge in photography – how to produce pictures which have interesting content and meaning. Can you communicate to other people through what you ‘say’ visually, be this simple humour (Figure 1.4) or some serious comment on the human condition like Figure 5.5?

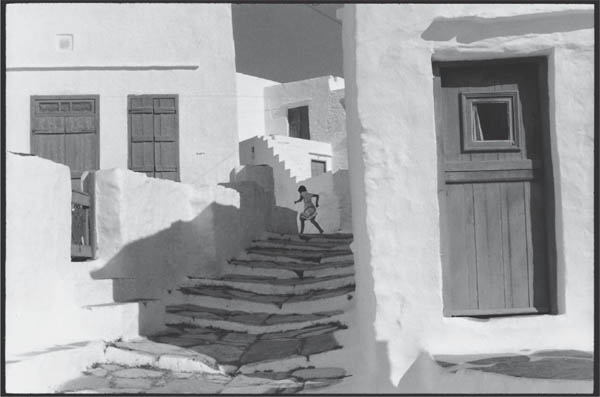

The way you visually compose your pictures is as important as their technical quality. But this skill is acquired with experience as much as learnt. Composition is to do with showing things in the strongest, most effective way, whatever your subject. Often this means avoiding clutter and confusion between the various elements present (unless this very confusion contributes to the mood you want to create). It involves you in the use of lines, shapes and areas of tone within your picture, irrespective of what the items actually are, so that they relate together effectively, with a satisfying kind of geometry (see Figure 1.5).

Composition is therefore something photography has in common with drawing, painting and the fine arts generally. The main difference is that you have to get most of it right while the subject is still in front of you, making the best use of what is present at the time. The camera works fast. Even digital methods do not offer as many opportunities to gradually build up your final image afterwards as does a pencil or brush.

‘Rules’ of composition have gone out of fashion, with good reason. They encourage results which slavishly follow the rules but offer nothing else besides. As Edward Weston once wrote: ‘Consulting rules of composition before shooting is like consulting laws of gravity before going for a walk.’ Of course it is easy to say this when you already have an experienced eye for picture making, but guides are helpful if you are just beginning (see Chapter 8). Practise making critical comparisons between pictures that structurally ‘work’ and those that do not. Discuss these aspects with other people, both photographers and non-photographers.

Where a subject permits, it is always good advice to shoot several photographs – perhaps the obvious versions first, then others with small changes in the way items are juxtapositioned, etc., increasingly simplifying and strengthening what your image expresses or shows. It’s your eye that counts here more than the camera (although some cameras get far less in the way between you and the subject than others).

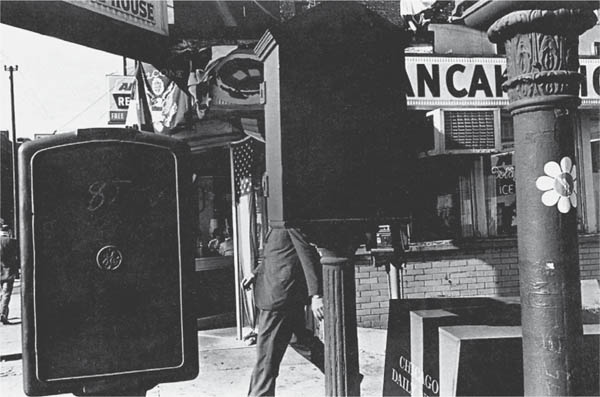

Composition can contribute greatly to the style and originality of your pictures. Some photographers (Lee Friedlander, for example: Figure 1.6) go for offbeat constructions which add to the weirdness of picture contents. Others, like Arnold Newman and Henri Cartier-Bresson, are known for their more formal approach to picture composition.

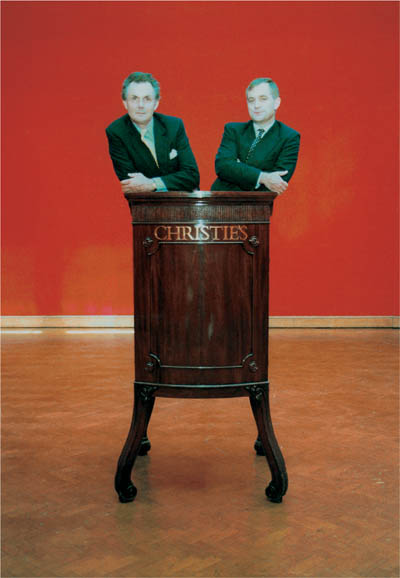

Figure 1.4 Pictures for financial newspapers don’t have to be dull. The photographer recognized the visual potential of this antique auctioneer’s box for his two portraits. Care over camera and figure positioning gives an eyecatching image of great simplicity. Brendan Corr for Financial Times

Composition in photography is almost as varied as composition in music or words – melodic or atonal, safe or daring – and can enhance subject, theme, and style. Every photograph you take involves you in some compositional decision, even if this is simply where to set up the camera or when to press the button.

There is little point in being technically confident and having an eye for composition, if you do not also understand why you are taking the photograph. The purpose may be simple – a clear, objective record of something or somebody for identification. It may be more nebulous – a subjective picture putting over the concept of security, happiness or menace, for example. No writer would pick up a pen without knowing whether the task is to produce a data sheet or a poem. Yet there is a terrible danger with photography that you set up your equipment, busy yourself with focus, exposure and composition, but think hardly at all about the meaning of your picture and why you should show the subject in that particular way.

Figure 1.5 Siphnos, Greece, 1961. A Henri Cartier-Bresson picture strongly designed through choice of viewpoint to use line and tone, together with moment in time

People take photographs for all sorts of reasons of course. Most are just reminders of vacations, or family and loved ones. These fulfil one of photography’s most valuable social functions, freezing moments in our own history for recall in years to come.

Sometimes photographs are taken to show tough human conditions and so appeal to the consciences of others. Here you may have to investigate the subject in a way which in other circumstances would be called prying or voyeurism. This difficult relationship with the subject has to be overcome if your final picture is to win a positive response from the viewer.

Understanding the best approach to the subject to create the right reaction from your target audience is vital too in photographs that advertise and sell. Every detail in a set-up situation must be considered with the message in mind. Is the location or background of a kind with which consumers positively identify? Are the models and the clothes they are wearing too up (or down) market? Props and accessories must suit the lifestyle and atmosphere you are trying to convey. Generally viewers must be offered an image of themselves made more attractive by the product or service you are trying to sell. In the middle of all this fantasy you must produce a picture structured to attract attention; show the product; perhaps leave room for lettering; and suit the proportions of the showcard or magazine page on which it will finally be printed.

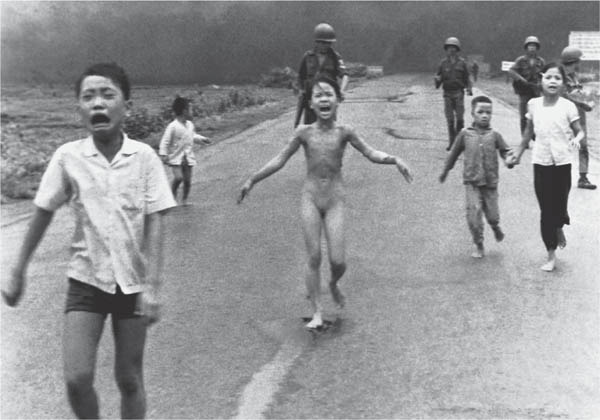

News pictures are different again. Here you must often encapsulate an event in what will be one final published shot. The moment of expression or action should sum up the situation, although you can colour your report by choosing what, when, and from where, you shoot. Until recently there was a long-held assumption that photographers are impartial observers, documenting events as they unfold. Reality is somewhat different, for no-one can be completely impartial. Photographers have their own beliefs and prejudices.

Photograph a demonstration from behind a police line and you may show menacing crowds; photograph from the front of the crowd and you show suppressive authorities. You have a similar power when portraying the face of, say, a politician or a sportsperson. Someone’s expression can change between sadness, joy, boredom, concern, arrogance, etc., all within the space of a few minutes. By photographing just one of those moments and labelling it with a caption reporting the event, it is not difficult to tinker with the truth. The ease by which digital manipulation can now add or remove picture elements seamlessly, described in Chapter 14, has further put to rest the old adage of ‘photographic truth’ and ‘the camera cannot lie’.

Figure 1.6 Lee Friedlander’s Chicago street scene seems random in composition and timing – with every object cut into by something else. However, it purposely expresses an off-beat, depersonalized strangeness. The picture leaves the viewer asking questions

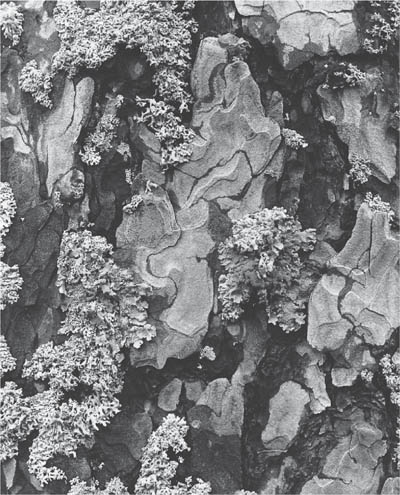

At another level, entirely decorative photographs for calendars or editorial illustration (pictures which accompany magazine articles) can communicate beauty for its own sake – beauty of landscape, human beauty, and natural form or beauty seen in ordinary everyday things (Figure 1.9). Beauty is a very subjective quality, influenced by attitudes and experience. But there is scope here for your own way of seeing and responding to be shown through a photograph which produces a similar response in others. Overdone, it easily becomes ‘cute’ and cloying, overmannered and self-conscious.

Photography can provide information in the kind of record pictures used for training, medicine, and various kinds of scientific evidence. Here you can really make use of the medium’s superb detail and clarity, and the way pictures communicate internationally, without the language barrier of the written word. Features of a camera-formed image are not unlike an eye-formed image (Chapter 3). This seems to make it easier to identify with and read information direct from a photograph than from a sketch.

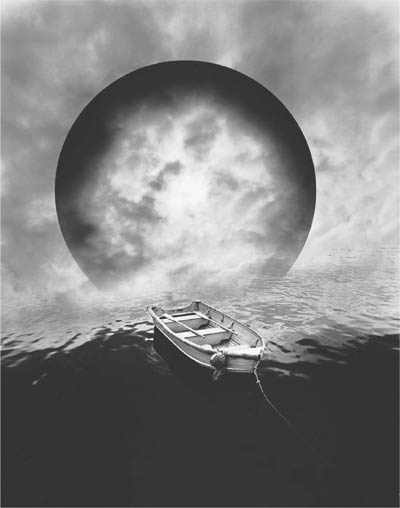

Photographs are not always intended to communicate with other people, however. You might be looking for self-fulfilment and self-expression, and it may be a matter of indifference to you whether others read information or messages into your results – or indeed see them at all. Some of the most original images in photography have been produced in this way, totally free of commercial or artistic conventions, often the result of someone’s private and personal obsession. You will find examples in the photography of Diane Arbus, Clarence Laughlin or Jerry Uelsmann (Figure 1.10), and photograms by Man Ray or Moholy Nagy.

Figure 1.7 Children fleeing an American napalm strike, 1972. Nick Ut photographed these Vietnamese youngsters burnt by bombs, which produced the curtain of smoke from the village behind them. Published worldwide, it helped solidify public opposition within the US against the war

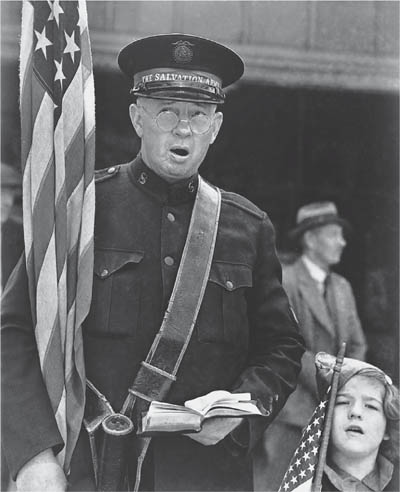

Figure 1.8 This documentary shot by Dorothea Lange was taken in San Francisco during the 1930s Depression. It relies greatly on human expressions to communicate an ‘in America we trust’ appeal

There are many other roles photographs can play: mixtures of fact and fiction, art and science, communication and non-communication. Remember too that a photograph is not necessarily the last link in the chain between subject and viewer. Editors, art editors, and exhibition organizers all like to impose their own will on final presentation. Pictures are cropped, captions are written and added, layouts place one picture where it relates to others. Any of these acts can strengthen, weaken or distort what a photographer is trying to show. You are at the mercy of people ‘farther down the line’. They can even sabotage you years later, by taking an old picture and making it do new tricks.

Changing attitudes towards photography

Today’s awareness and acceptance of photography as a creative medium by other artists, by galleries, publishers, collectors and the general public has not been won easily. People’s views for and against photography have varied enormously in the past, according to the fashions and attitudes of the times. For a great deal of the nineteenth century (photography was invented in 1839) photographers were seen as a threat by painters who never failed to point out in public that these crass interlopers had no artistic ability or knowledge. To some extent this was true – you needed to be something of a chemist to get results at all.

Pictorialism and realism

By the beginning of the twentieth century equipment and materials had become somewhat easier to handle. Snapshot cameras, and developing and printing services for amateurs, made black and white photography an amusement for the masses. In their need to distance themselves from all this and gain acceptance as artists, ‘serious’ photographers tried to force the medium closer to the appearance and functions of paintings of the day. They called themselves ‘pictorial’ photographers, shooting picturesque subjects, often through soft-focus camera attachments, and printing on textured paper by processes which eliminated most of photography’s ‘horrid detail’.

Figure 1.9 Fungus and bark on a tree trunk. The detail and tone range offered by ‘straight’ photography strengthen the subject’s own natural qualities of pattern and form

Figure 1.10 A dream-like image constructed by Jerry Uelsmann – printed from several negatives onto one piece of paper. The apparent truthfulness of photography makes it a convincing medium for surreal pictures (see also montage by digital means, page 279)

Fortunately the advent of cubism and other forms of abstraction in painting, at the same time as techniques for mechanically reproducing photographs on the printed page, expanded photographers’ horizons. As a reaction to pictorialism ‘Straight’ photography came into vogue early in the twentieth century with the work of Edward Weston (page 133), Paul Strand and Albert Renger-Patzsch. They made maximum use of the qualities of black and white photography previously condemned: pinsharp focus throughout, rich tonal scale and the ability to shoot simple everyday subjects using natural lighting. Technical excellence was all important and strictly applied. Photography had an aesthetic of its own, but something quite separate from painting and other forms of fine art.

The advent of photographs mechanically printed into newspapers and magazines opened up the market for press and candid photography. Pictures were taken for their action and content rather than any greatly considered treatment. This and the freedom given by precision hand cameras led to a break with age-old painterly rules of composition.

Figure 1.11 ‘La Lettre’ by Robert Demachy. A 1905 example of pictorial (or ‘picturesque’) subject and style. Demachy made his prints by the gum bichromate chemical process, which gives an appearance superficially more like an impressionist painting than a photograph

The 1930s and 40s were the great expansion period for picture magazines and photo-reporting, before the growth of television. They also saw a steady growth in professional aspects of photography: advertising; commercial and industrial; portraiture; medical; scientific and aerial applications. Most of this was still in black and white. Use of colour gradually grew during the 1950s but it was still difficult and expensive to reproduce well in publications.

Youthful approach of the 1960s

Rapid, far-reaching changes took place during the 1960s. From something which a previous generation had regarded as an old-fashioned, fuddy-duddy trade and would-be artistic occupation, photography became very much part of the youth cult of the ‘swinging sixties’. New small-format precision SLR cameras, electronic flash, machines and custom laboratories to hive off boring processing routines, and an explosion of fashion photography, all had their effect. Photography captured the public imagination.

Young people suddenly wanted to own a camera, and use it to express themselves about the world around them. The new photographers were interested in contemporary artists, but neither knew nor cared about the established photographic clubs and societies with their stultifying ‘rules’ and narrow outlook on the kind of pictures acceptable for awards.

The fresh air this swept into photography did immeasurable good. Photographers were no longer plagued with self-conscious doubts such as ‘is photography Art?’ It began to become accepted as a medium – already the dominant form of illustration everywhere and, in the hands of an artist, a growing art form. Since photographs grew so universal in people’s contemporary life-style they became integrated with modern painting, printmaking, even sculpture.

Photography began to be taught in schools and colleges, especially art colleges, where it had been previously down-graded as a technical subject. America led the way in setting up photographic university degree courses, and including it in art and design, social studies and communications. Nevertheless, few one-person portfolios of photographs had been published with high quality reproduction in books. It was also extremely rare for an established art gallery to sell or even hang photographs, let alone public galleries to be devoted to photography. As a result it was difficult for the work of individuals to be seen and become well-known. Even magazines and newspapers failed to credit the photographer alongside his or her work, whereas writers always had a published credit.

By the 1970s though all this had changed. Adventurous galleries put on photography shows which were increasingly well attended. Demand from the public and from students on courses encouraged publishers to produce a wide range of books showcasing the work of individual photographers. Creative work began to be sold as ‘fine prints’ in galleries to people who bought them as investments. Older photographers such as Bill Brandt, Minor White and André Kertesz were rediscovered by art curators, brought out of semi-obscurity and their work exhibited in international art centres.

The 1980s brought colour materials which gave better quality results and were cheaper than before. Colour labs began to appear offering everyone better processing and printing, plus quicker turn-around. The general public wanted to shoot in colour rather than black and white, and gradually colour was taken up by artist photographers too. Colour became cheaper to reproduce on the printed page; even newspapers started to use colour photography.

Today the availability of less daunting, user-friendly camera equipment combined with a much bigger public audience for photography (and more willing to receive original ideas) encourages a broad flow of pictures. Galleries, books and education have brought greater critical discussion of photographs – how they communicate meanings through a visual language of their own. There are now so many ways photography is used by different individuals it is becoming almost as varied and profound as literature or music.

Personal styles and approaches

The ‘style’ of your photography will develop out of your own interests and attitudes, and the opportunities that come your way. For example, are you mostly interested in people or in objects and things you can work on without concern for human relationships? Do you enjoy the split-second timing needed for action photography, or prefer the slower more soul-searching approach possible with landscape or still-life subjects?

If you aim to be a professional photographer you may see yourself as a generalist, handling most photographic needs in your locality. Or you might work in some more specialized area, such as natural history, scientific research or medical photography, combining photography with other skills and knowledge. Some of these applications give very little scope for personal interpretation, especially when you must present information clearly and accurately to fulfil certain needs. There is greatest freedom in pictures taken by and for yourself. Here you can best develop your own visual style, provided you are able to motivate and drive yourself without the pressures and clear-cut aims present in most professional assignments.

Style is difficult to define, but recognizable when you see it. Pictures have some characteristic mix of subject matter, mood (humour, drama, romance, etc.), treatment (factual or abstract), use of tone or colour, composition … even the picture proportions. Technique is important too, from choice of lens to form of print presentation. But more than anything else style is to do with a particular way of seeing.

Figure 1.12 Tree frog jumping. A rapid sequence of three ultra-fast flash exposures made on one frame of film and shot in a specially devised laboratory setup, by Stephen Dalton. Time-andaction record photography provides unique subject information for natural history research and education

Figure 1.13 Colour photography was for a long time considered more life-like, and so less expressive than black and white. But a hand-coloured black and white print, like this portrait by Sue Wilks, allows you to emphasize chosen areas with total freedom

Content and meaning

You can’t force style. It comes out of doing, rather than of analysing too much, refined down over a long period to ways of working which best support the things you see as important and want to show others. It must not become a formula, a mould which makes everything you photograph turn out looking the same. The secret is to coax out the essence of each and every subject, without repeating yourself. People should be able to recognize your touch in a photograph but still discover things unique to each particular subject or situation by the way you show them.

In personal work the content and meaning of photographs can be enormously varied. A major project ‘Memory & Skin’ by Joy Gregory explores identity and how people in one part of the world view people in another. Her quiet observation explores connections between the Caribbean and Europe by tracing fragments of history. The picture Figure 1.15 is a cluttered mix of vague and specific detail but within the context of the series theme you can return to it several times and see new things. (Compare with Figure 1.14 which is instantly direct and graphic but contains less depth and meaning.)

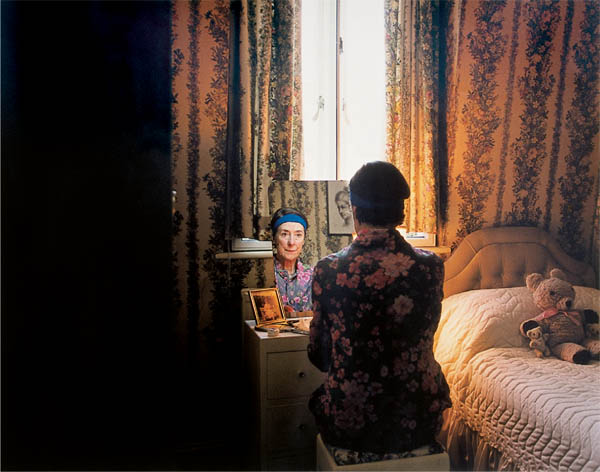

Hannah Starkey’s work is also about memory, real and imagined, forming a series on women’s lives in the inner city. Detailed and strongly narrative, her individually untitled pictures represent little moments of familiarity – the kind of undramatic, ordinary observations and experiences of life. In Figure 1.16 an ageing woman contemplates her reflection with both anxiety and pleasure. Other elements contained in the room say something about earlier times. And yet the whole series of Hannah’s pictures are not documentary but tableaux. Her people are posed by actresses and every item specially picked and positioned. Content and meaning rule here over authenticity, but are based on acute observation and meticulous planning. Bear in mind here that tableaux (pictures of constructed events) have a long history in photography. Victorians like Julia Margaret Cameron and H.P. Robinson produced many photographs narrating stories. This ‘staged’ approach has always of course been present in movies, and in most fashion and advertising still photography.

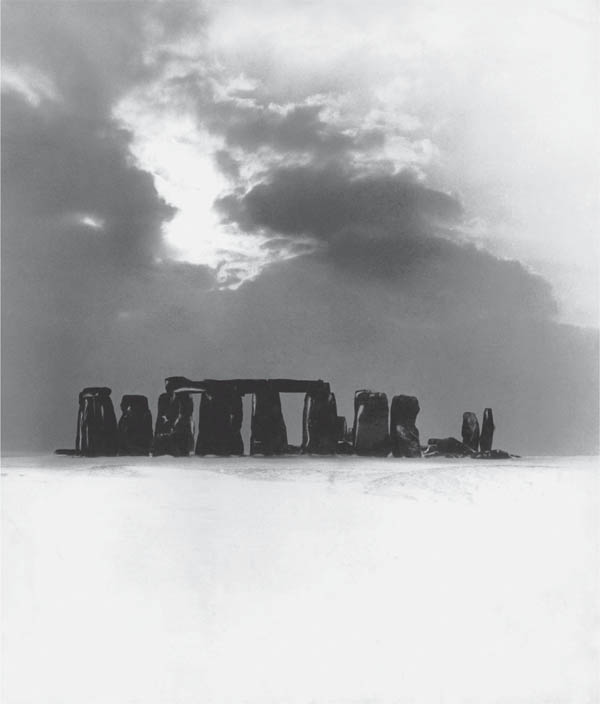

Figure 1.14 Stonehenge, England, under snow, by Bill Brandt. A dramatic black and white interpretative image of great simplicity. It was seen and photographed straight but printed with very careful control of tonal values

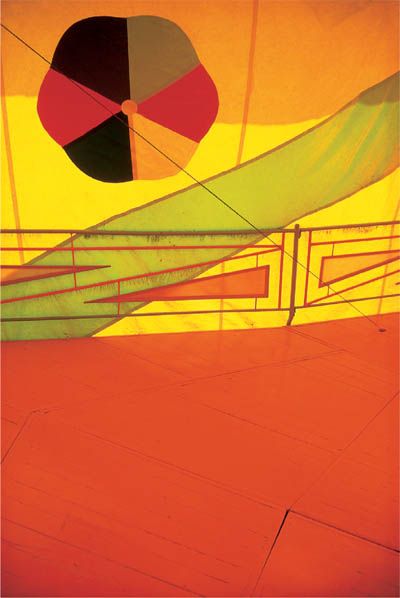

Sometimes the content of personal work is based on semi-abstract images in which elements such as colour, line and tone are more important than what the subject actually is. Meaning gives way to design and the photographer picks subjects for their basic graphic content which he or she can mould into interesting compositions. Figure 1.17 is one such example.

Look at collections of work by acknowledged masters of photography (single pictures, shown in this book, cannot do them justice): Henri Cartier-Bresson’s love of humanity, gentle humour and brilliant use of composition, Jerry Uelsmann’s surreal, viewer-challenging presentation of landscape, or Robert Demachy’s romantic pictorialism. Cindy Sherman, John Pfahl, Martin Parr and Mari Mahr are photographers who each have dramatically different approaches to content and meaning. Their work is distinctive, original, often obsessional.

Figure 1.15 Shop window, Nantes, France. A straight, thought provoking documentary shot from a project by Joy Gregory, ‘Memory & Skin’. Her pictures explore how people view others from a different part of the world

Figure 1.16 Untitled – February 1991. This picture by Hannah Starkey is one of her series entitled ‘Women Watching Women’. The content and meaning of each shot relate to little moments familiar to experiences in everyday life. The real and the fictional are combined here, see text

In the fields of scientific and technical illustration the factual requirements of photography make it less simple to detect individuals’ work. But even here high-speed photography by Dr Harold Edgerton and medical photography by Lennart Nilsson stand out, thanks to these experts’ concern for basic visual qualities too.

There is no formula way to judge the success of a photograph. We are all in danger of ‘wishful seeing’ in our own work, reading into pictures the things we want to discover, and recalling the difficulties overcome when shooting rather than assessing the result as it stands. Perhaps the easiest thing to judge is technical quality, although even here ‘good’ or ‘bad’ may depend on what best serves the mood and atmosphere of your picture.

Most commercial photographs can be judged against how well they fulfil their purpose, since they are in the communications business. A poster or magazine cover image, for example, must be striking and give its message fast. But many such pictures, although clever, are shallow and soon forgotten. There is much to be said for other kinds of photography in which ambiguity and strangeness challenge you, allowing you to keep discovering something new. This does not mean you have to like everything which is offbeat and obscure; there are as many boring, pretentious and charlatan workers in photography as in any other medium.

Figure 1.17 The subject is the inside of a circus tent – but content is mostly irrelevant in John Batho’s creative graphic composition concerned with colour and line. You might read it as landscape, or as flat, twodimensional abstract design – a piece of artwork complete in itself

Reactions to photographs change with time too. Live with your picture for a while (have a pinboard wall display at home) otherwise you will keep thinking your latest work is always the best. Similarly it is a mistake to surrender to today’s popular trend; it is better to develop the strength of your own outlook and skills until they gain attention for what they are. Just remember that although people say they want to see new ideas and approaches, they still tend to judge them in terms of yesterday’s accepted standards.

A great deal of professional photography is sponsored, commercialized art in which success can be measured financially. Personal projects allow most adventurous, avant-garde picture making – typically to express preoccupations and concerns. Artistic success is then measured in terms of the enjoyment and stimulus of making the picture, and satisfaction with the result. Rewards come as work published in its own right or exhibited on a gallery wall. Extending yourself in this way often feeds commercial assignments too. So the measure of true success could be said to be when you do your own self-expressive thing, but also find that people flock to your door to commission and buy this very photography.

• |

Photography is a medium – a vehicle for communicating facts or fictions, and for expressing ideas. It requires craftsmanship and artistic ability in varying proportions. |

• |

Technical knowledge is necessary if you want to make full use of your tools and so work with confidence. Knowing ‘how’ frees you to concentrate on ‘what’ and ‘why’ (the photograph’s content and meaning). |

• |

Always explore new processes and equipment as they come along. Discover what kind of images they allow you to make. |

• |

Traditionally in photography the image of your subject formed by the camera lens is recorded on silver halide coated film. Processing is by liquid chemicals, working in darkness. |

• |

New technology now allows us the option of capturing the lens image by electronic digital means. Results can also be manipulated digitally, using a computer. You don’t need chemicals or a darkroom. |

• |

Visually, camera work in colour is easier than black and white. Colour is more complex in the darkroom. |

• |

Photography records with immense detail, and in the past had a reputation for being essentially objective and truthful. But you can use it in all sorts of other ways, from propaganda to ‘fine art’ self-expression. |

• |

Taking photographs calls for a mixture of (a) carefully followed routines and craft skills, to control results, and (b) creative decisions about subject matter and the intention of your picture. |

• |

Photographs can be enjoyed/criticized for their subject content, or their structure, or their technical qualities, or their meaning, individually or together. |

• |

The public once viewed photography as a stuffy, narrow pseudo-art, but it has since broadened into both a lively occupation and a creative medium, exhibited everywhere. |

• |

Developing an eye for composition helps to simplify and strengthen the point of your picture. Learn from other photographers’ pictures but don’t let their ways of seeing get in the way of your own response to subjects. Avoid slavishly copying their style. |

Success might be gauged from how well your picture fulfils its intended purpose. It might be measured in technical, financial or purely artistic terms, or in how effectively it communicates to other people. In an ideal world all these aspects come together. |

When you are working on projects it is helpful to maintain your own visual notebook. This might be a mixture of scrapbook and diary containing written or sketched ideas for future pictures, plus quotes and work by other photographers, writers or artists which you want to remember (add notes of your own). It can also log technical data, lighting diagrams and contact prints relating to shots planned or already taken.

The projects below can be completed in either written or verbal (discursive) form, but they must include visual material such as prints, photocopies or slides.

1 |

Find and compare examples of people photographs which differ greatly in their function and approach. Some suggested photographers: Cecil Beaton, Diane Arbus, Yousuf Karsh, Dorothea Lange, Elliott Erwitt, Julia Margaret Cameron, August Sander, Martin Parr, Cindy Sherman, Arnold Newman. |

2 |

Compare the landscape work of three of the following photographers, in terms of their content and style: Ansel Adams, Franco Fontana, Bill Brandt, Alexander Keighley, Joel Meyerowitz, Fay Godwin, John Blakemore. |

3 |

Looking through newspapers, magazines, books, etc., find examples of photographs (a) which provide objective, strictly factual information; and (b) others which strongly express a particular point of view, either for sales promotion or social or political purposes. Comment on their effectiveness. |

4 |

Shoot four examples of photographs in which picture structure is more important than actual subject content. In preparation for this project look at work by some of the following photographers: Ralph Gibson, André Kertesz, Lee Friedlander, Paul Strand, Laszlo Moholy Nagy, Barbara Kasten, Karl Blossfeldt. |

5 |

Find published photographs which are either (a) changed in meaning because of adjacent text or caption, or by juxtaposition with other illustrations; or (b) changed in significance by the passing of time. |